Introduction

Assessing community need for healthcare services is challenging, with referral rates, triage patterns and wait times commonly used as indicators of demand1,2. There is limited available data describing patterns associated with paediatric outpatient services, particularly in rural settings where resources are finite due to maldistribution of the medical workforce, a well-documented issue1,3-6. Collection and reporting of such data is imperative to determine community need and align services appropriately. The establishment of a new paediatric outpatient service provided a unique opportunity to assess the latent demand within a community.

Portland District Health (PDH), a public health service in south-western Victoria, Australia, established a new paediatric outpatient service in 2018. The town of Portland is geographically classified as Modified Monash 4 (MM4; medium rural town) and is the largest town in the Glenelg Local Government Area (LGA), with a catchment population of 19 563, and 6219 km2 in area7,8. The paediatric population of the LGA is 43688. The aim of establishing the new paediatric service was to meet the perceived community demand and provide timely, accessible care closer to patients’ homes. During the initial year of the paediatric service a sole paediatrician was employed 4 days per week and conducted consulting sessions at the public outpatient clinic four sessions per week (2 days). Prior to the establishment of this local service, the nearest paediatric outpatient service was based in a regional centre (MM3), a distance of approximately 100 km by road, and provided a visiting service to PDH approximately once per month7.

There has been an increase in referrals to general paediatricians over recent years, believed to be facilitated by children presenting with more complex behavioural and developmental problems, which are challenging and time consuming to manage in general practice9-11. This increase in referrals to paediatricians is coupled with a changing pattern in primary care delivery, with paediatric presentations making up a smaller overall proportion of GP visits12,13. There is limited reporting on burden of disease trends in rural locations; however, one recent study analysing paediatric conditions found 59.2% of patients had behavioural or developmental problems, 28.6% had medical problems and 12.1% had a combination of problems9. This article aims to contribute to the limited data on the referral and triage patterns associated with a rural health service’s paediatric outpatient clinic by examining the first 12 months of a newly established service.

Methods

A retrospective review of referrals for all patients who had an initial consultation during the first 12 months of the new paediatric outpatient service was conducted. The data collection period was October 2018 to October 2019, with associated referrals dated from July 2018 to September 2019. Referral data were extracted, categorised and de-identified by a PDH staff member prior to sending to the researchers for analysis. Referrals made to the clinic where the patient did not make or attend an appointment were excluded from the study. This was due to the data collection method that extracted information from completed appointment records. Any review consultations during the 12-month period were also excluded.

Data extracted included referral date, source of referral, initial appointment date, patient demographics and problem type. Referral problem types were triaged by the paediatrician as physical, behavioural/developmental or a combination of types (both physical and behavioural/developmental). Problems were analysed by age group: infants(<1 year), pre-schoolers (1–5 years), children of primary school age (6–12 years) and adolescents (13–18 years).

Statistical analyses were undertaken using the software package SPSS v27 (IBM Corp; https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics). Descriptive statistics were performed for all variables, with Pearson’s χ2 test used for categoric variables to determine relationships of significance, with a p-value of less than 0.05 determined significant. Referral rates were calculated per 1000 head of the LGA population 0–19 years only and using available age group data (0–4, 5–9, 10–14, 15–19 years)8.

Ethics approval

The project received ethics approval from South West Healthcare Human Research Ethics Committee (2020-15).

Results

Participants

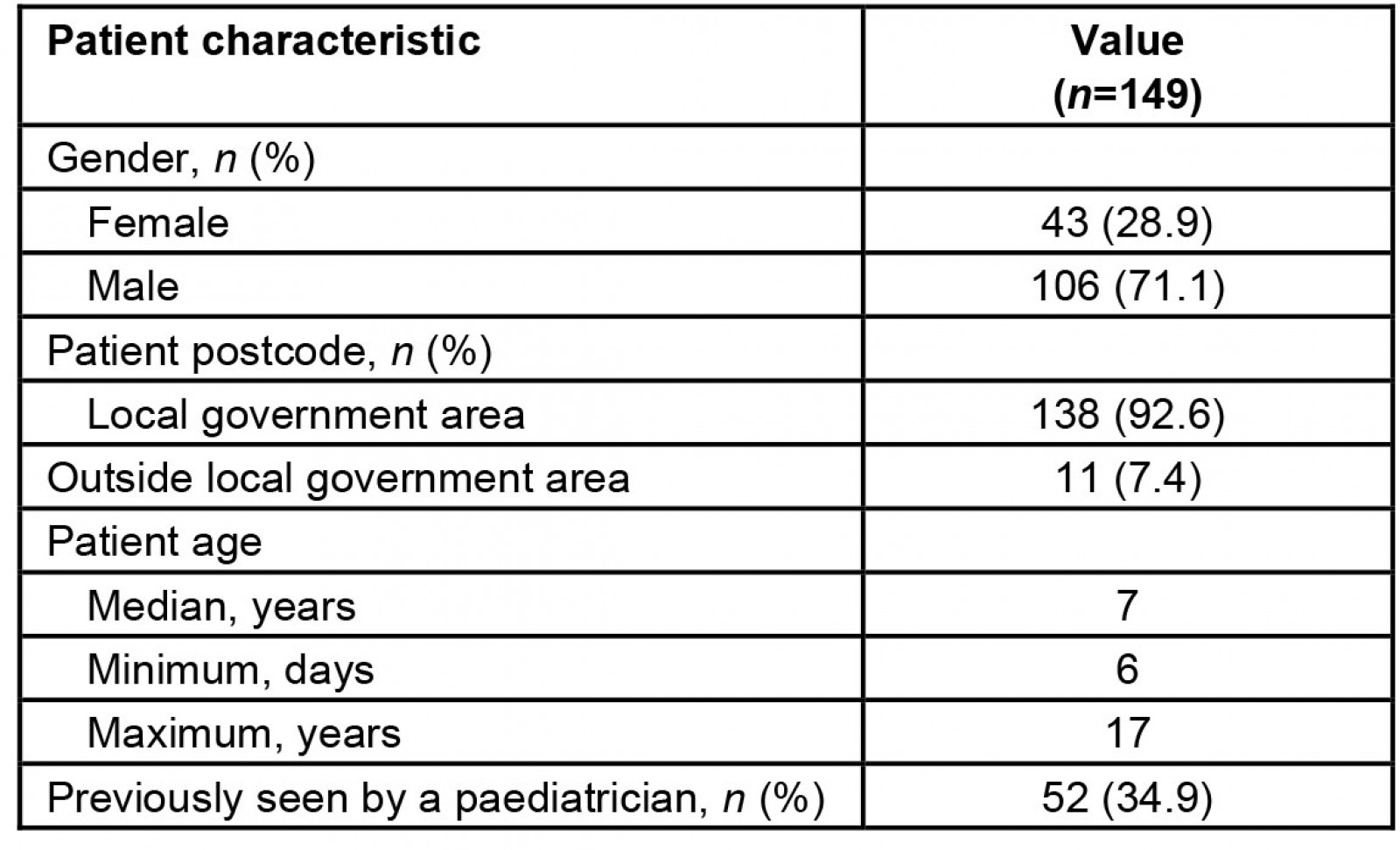

There were 149 referrals for new patients who attended an initial appointment during the study period, with significantly more referrals for males (71.1%). Patient age range was 6 days to 17 years, with a median age of 7 years. A total of 52 patients (34.9%) had previously been seen by a paediatrician (Table 1).

Table 1: Patient demographic data

Referral data

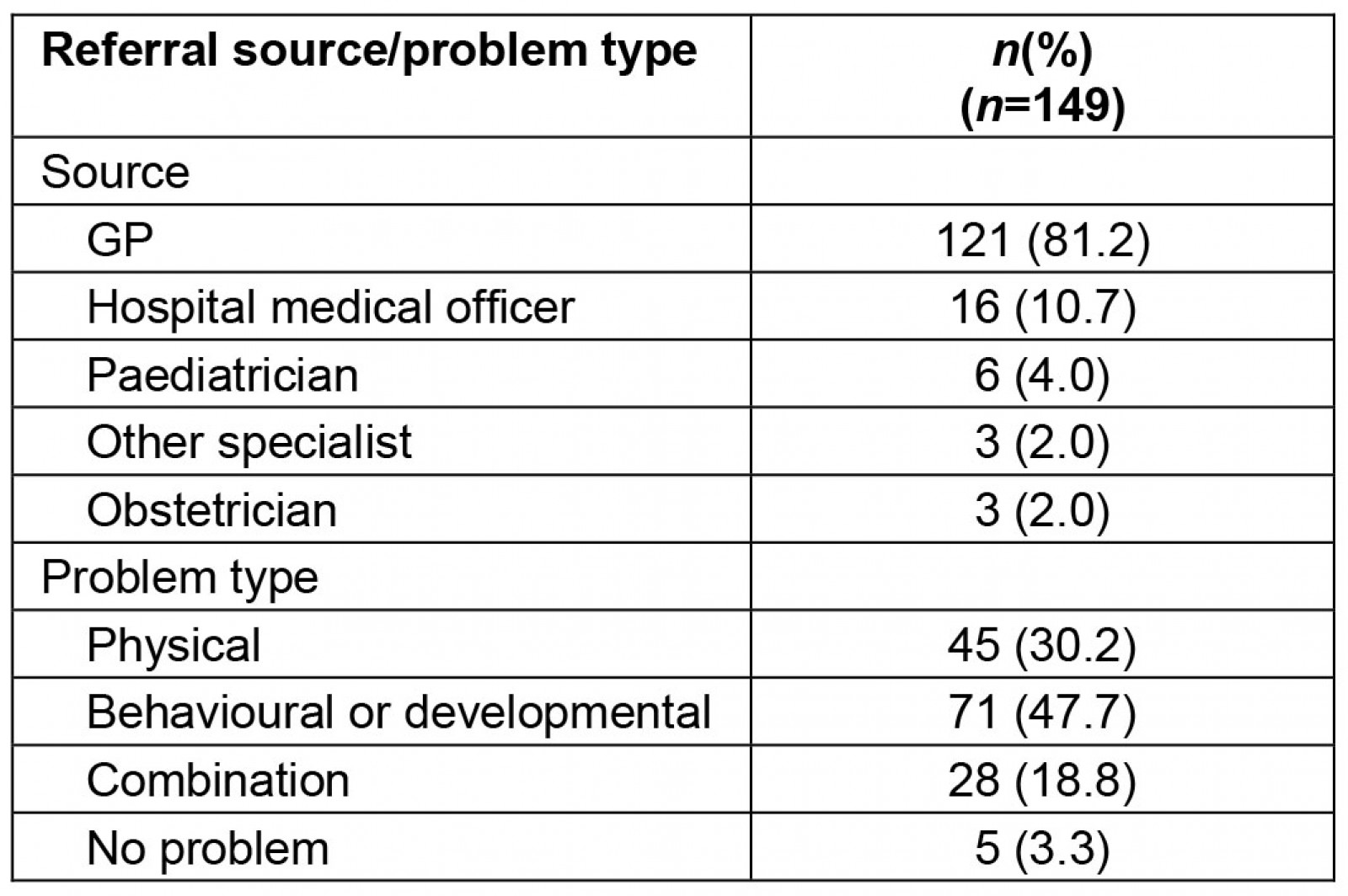

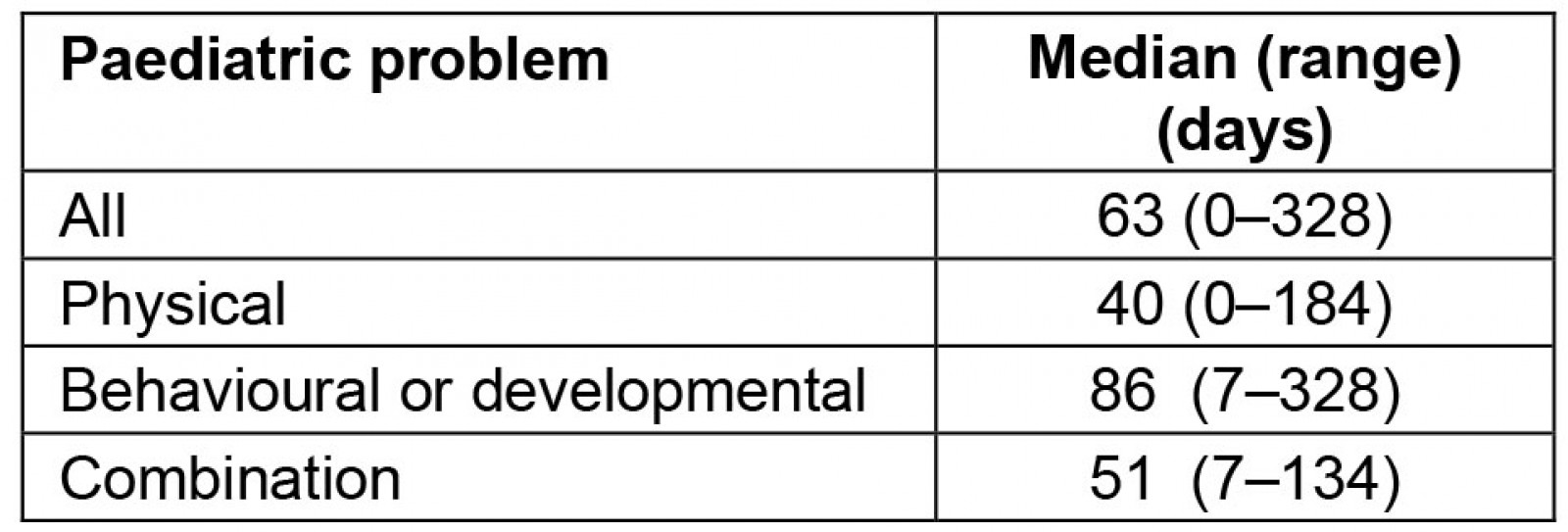

Most referrals were from GPs (81.2%) (Table 2). The median time from referral letter date to initial appointment was 63 days. The median wait time for patients with physical problems was 40 days, compared with 86 days for patients with behavioural/developmental problems (Table 3).

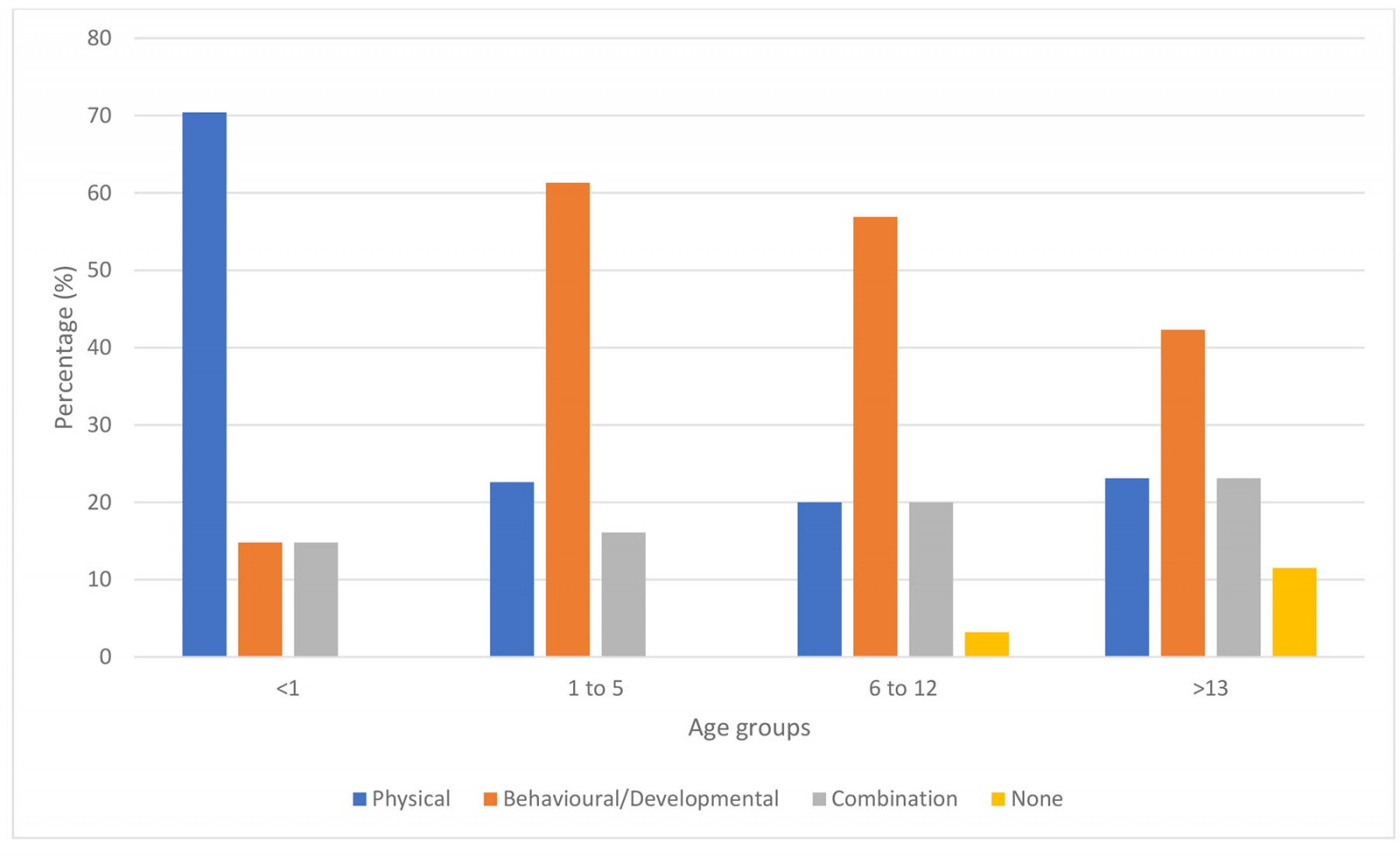

A total of 47.7% of referrals were triaged as behavioural/developmental conditions, 30.2% as physical conditions and 18.8% as a combination (Table 2). There were significant differences in referral problems between age groups, with 61.3% of children aged 1–5 years triaged as having behavioural/developmental problems, while 70.4% of children aged <1 year were triaged as having a physical problem (p≤0.001) (Fig1).

Table 2: Paediatric referrals within the Glenelg Local Government Area, by referral source and problem type

Table 3: Paediatric appointment wait times within the Glenelg Local Government Area, from referral date to initial appointment

Figure 1: Problems referred to a paediatrician within the Glenelg Local Government Area, by age group.

Figure 1: Problems referred to a paediatrician within the Glenelg Local Government Area, by age group.

Referral rates within Local Government Area

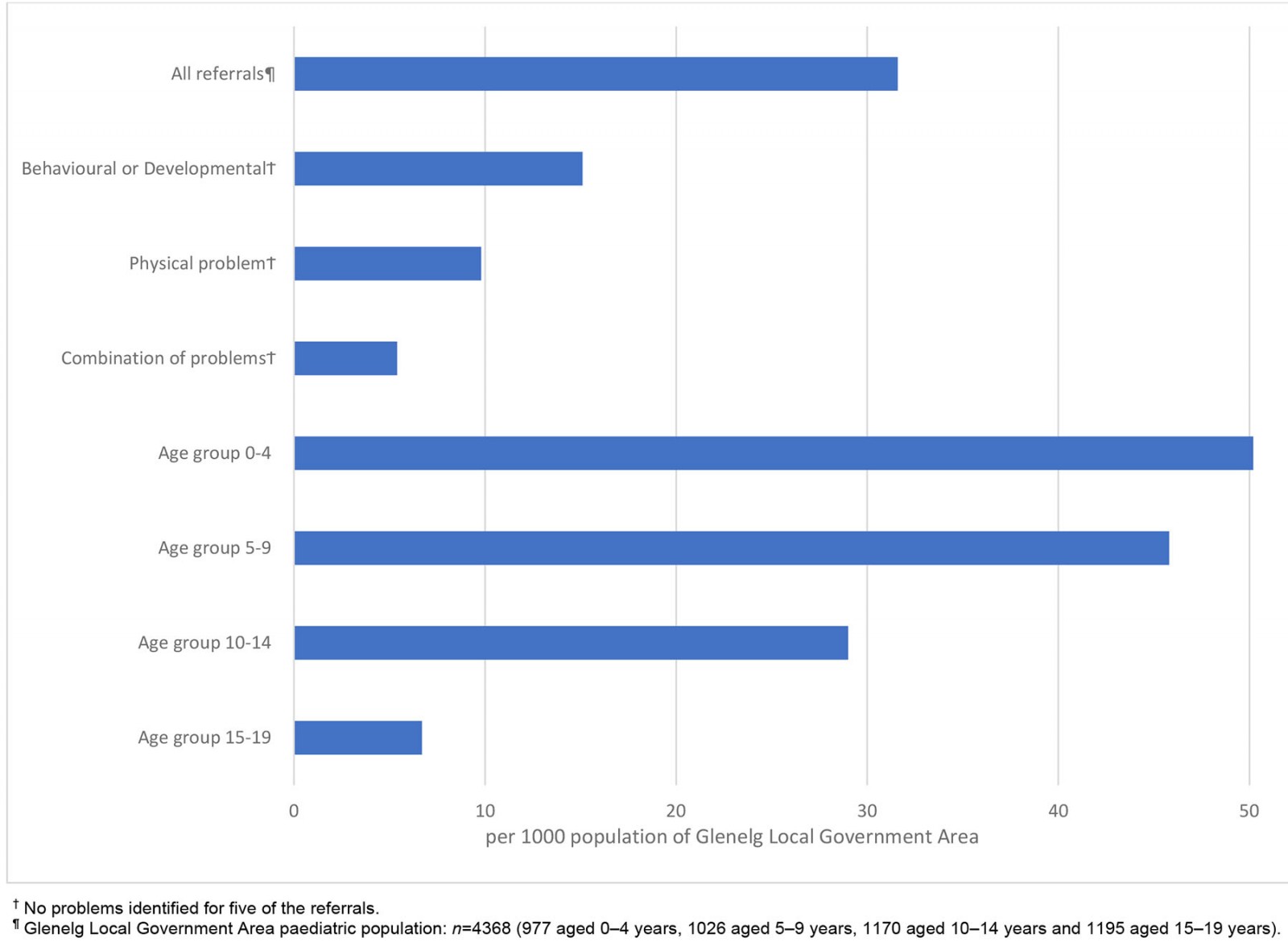

There was a total of 92.6% (138) of referrals within the Glenelg LGA, equating to a referral rate of 31.6 referrals per 1000 children aged 0–19 years. The referral rate decreased with increasing patient age group (Fig2).

Patients triaged as having behavioural/developmental problems had the highest referral rate, 15.1 per 1000, compared to patients who were referred for physical problems or a combination of problems, at 9.8 and 5.4 per 1000, respectively (Fig2).

Figure 2: Paediatric referral rates within the Glenelg Local Government Area, by problem and age group.

Figure 2: Paediatric referral rates within the Glenelg Local Government Area, by problem and age group.

Discussion

There is an absence of contemporary data on referral rates to paediatric outpatient clinics in Australia, with one study estimating that 10% of a paediatric population were referred to their service during a period of 12 months14. International data have estimated referral rates of 10–20 per 10006,15. This study’s finding of a referral rate within the Glenelg LGA of 31.6 per 1000 demonstrates a higher referral rate than has been previously reported and a latent community need for this service. Collection of data in subsequent years would be helpful to determine whether this high referral rate during the service’s initial year is sustained.

A salient finding was that 65.2% of patients had not previously seen a paediatrician, highlighting that this need was not being adequately met by the visiting service. A barrier to accessing health care for rural children is distances from services, with evidence demonstrating that locating community paediatric services closer to home increases access to care, ultimately improving patient outcomes1,10,16. Rural communities with similar geographic classification to Portland (MM4) have 0.3 per 1000 non-GP specialists (including paediatricians) compared to 2.6 per 1000 in metropolitan centres (MM1)3. The reduced access to health services and poorer health outcomes of rural children are further compounded by a greater exposure to myriad adverse social determinants of health in rural areas such as higher rates of poverty and social isolation, and less engagement with early childhood intervention (an education and care service) compared to their metropolitan and regional counterparts1.

The high proportion of referrals triaged as having behavioural/developmental problems (66.5%) is a noteworthy feature of this patient profile and is consistent with increases in these problems in both metropolitan and rural settings, which report the figure as high as 70%9,11. Data from the Australian Educational Developmental Census found that, between 2009 and 2021, the percentage of children in the Glenelg LGA considered developmentally vulnerable in one or more domains increased from 15% to 24.2%17. This is higher than both the state and national averages (2021) of 19.9% and 22%, respectively17. The lack of early childhood intervention services in rural Australia compromises access to early interventions, contributing to increasing rates of behavioural/developmental problems1. Early intervention is paramount as evidence suggests delayed intervention is less effective1. The localised service may go some way to addressing this, with high referral rates in the age groups of 0–4 and 5–9 years for behavioural/developmental problems allowing for earlier engagement with a paediatrician and referral to appropriate services.

The high referral rate and high proportion of behavioural/developmental problems resulted in extended wait times. Such delays have been shown to place added pressure on primary care, exacerbate symptoms, delay pharmacological interventions and negatively influence mental health of parents2,18-20. Public paediatric outpatient clinics have been found to have longer wait times for behavioural/developmental appointments compared to private clinics, with a 2020 report finding a median wait time for behavioural/developmental problems of 31 days for private clinics in rural Victoria and South Australia20.

Further research will be undertaken to examine more closely the case-mix data of this new service, including the problems identified during the initial consultation and the outcomes of the consultation.

Limitations

Due to resource constraints, data on specific conditions within each problem domain, review appointments and referrals for patients who did not attend their initial appointment were not extracted. The latter may underestimate the referral rate and community’s disease burden.

Conclusion

The establishment of this new rural paediatric service uncovered an unmet need within the PDH’s LGA, evidenced by both high referral rates and a majority patient population who had not previously seen a paediatrician. The greatest area of need identified by referral analysis was for behavioural and developmental problems. This study illustrates the importance of providing accessible care within rural communities and the significant potential this has to enable early interventions that improve children’s health and development.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Nicola Taylor from Portland District Health for extraction and de-identification of data.