Introduction

Described as the ‘stethoscope of the future’, point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) refers to ultrasound that is performed and interpreted in real time. While POCUS adds significant value to consultations as an adjunct to clinical history and physical examination1,2, it is not intended to be a substitute for formal ultrasound. The potential benefits of POCUS may be greatest in rural areas where there is limited access to ultrasound imaging services. In Australia, only 14% of radiologists live in rural areas, and there is a chronic national shortage of sonographers3. POCUS may help to address this gap, reducing the need for rural patient transfers to access imaging services2-4.

Part of the value of POCUS is its applicability across a wide range of presentations and procedures2,5,6, with potential benefits including reducing time to diagnosis and treatment, shortening stay length in emergency departments and increasing rural access2,7,8. It is important, however, to recognise that clinicians are more likely to utilise POCUS as a screening tool, seeking to rule in/out some diagnoses promptly (eg presence of intrauterine pregnancy) rather than as a replacement for comprehensive ultrasound.

While there are significant applications for rural emergency and general practice, there is limited understanding of how POCUS may be implemented by rural general practitioners (GPs) in Australia9. The aim of this exploratory study was to examine how POCUS is adopted, including the range and frequency of clinical activities for which it is used, when machines are accessible in rural general practice.

Methods

Study design and setting

This exploratory study was conducted in four teaching general practices in rural South Australia, including one inner regional, two outer regional and one remote (populations 16 600, 12 900, 3300 and 3600, respectively)10. GPs in each practice supervised penultimate-year medical students during their rural clinical school year-long training. A Mindray TE7 portable ultrasound machine was provided in each practice for the duration of the study period (July 2020 to June 2021). Each location except the remote site has formal sonography services available.

Participants and data collection

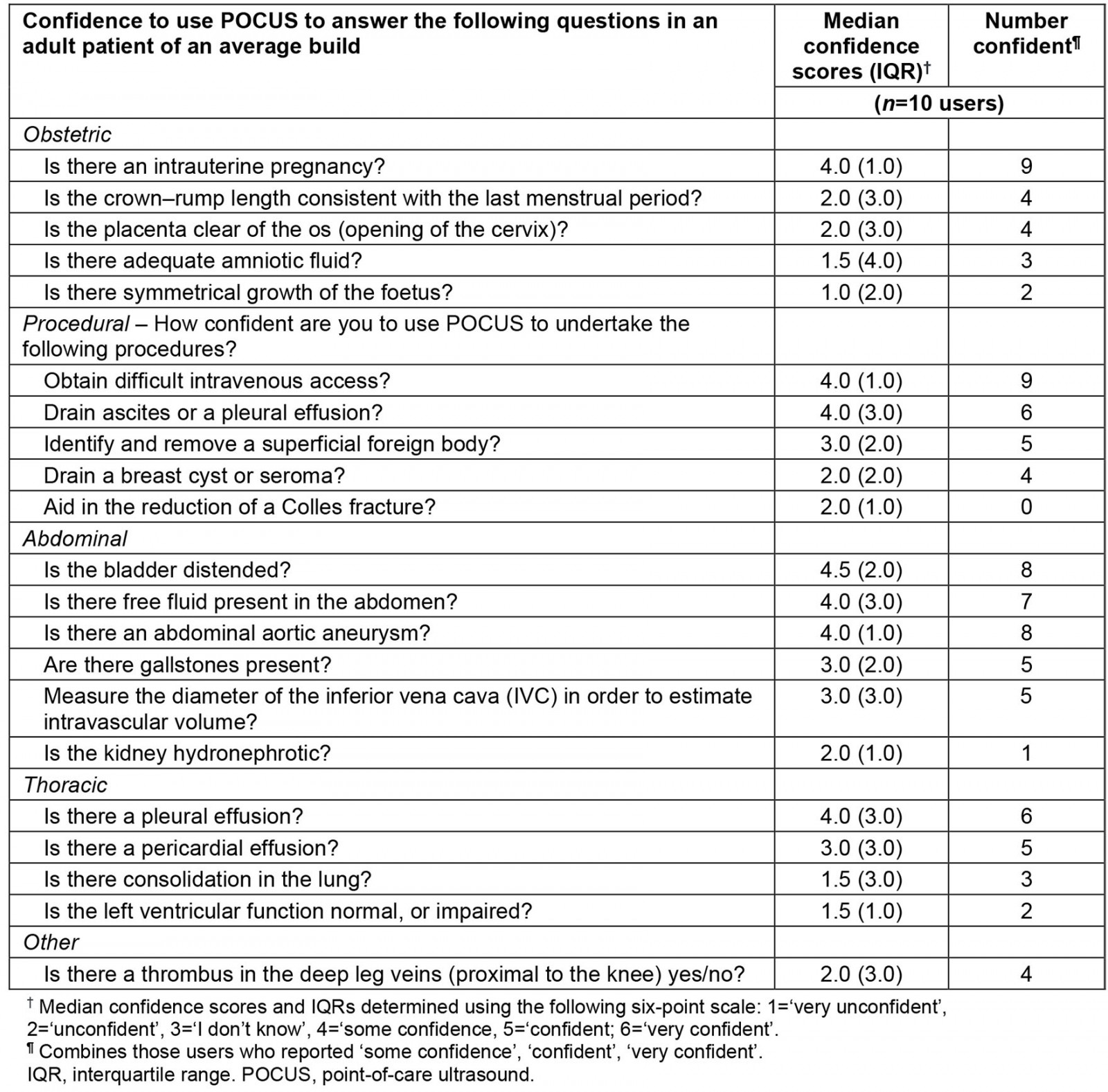

Practice medical staff were invited to participate as ‘users’ (ie operators) of the POCUS machines. Prior to use, participants were asked to complete a short online survey (SurveyMonkey®) to collect their demographic information, roles, previous access to POCUS or ultrasound training, and current POCUS confidence (Table 1). Confidence was recorded using a six-point scale (1=‘very unconfident’, 2=‘unconfident’, 3=‘I don’t know’, 4=‘some confidence’, 5=‘confident’, 6=‘very confident’).

Users were offered access to POCUS training during the study, with at least one clinician from each practice completing a 1- or 2-day POCUS training course to familiarise themselves with the Mindray scanner and practise several techniques. The training was provided through the LearnEM Bedside Emergency Ultrasound Program®11. Mannequins were available, and volunteers participated in all training sessions.

All ‘users’ were requested to record details of their POCUS activity (ie user’s unique code, clinic identifier, date of examination, clinical indication, purpose (clinical, teaching or learning/self-practice) and body region examined). Patient information or images were not extracted. These details were recorded within each practice using a proforma and collected monthly by the research team. Clinical indications were coded by two clinical researchers (DAG and LW).

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as absolute and relative frequencies. Median confidence scores with interquartile ranges (IQR) were determined from users’ survey responses on the six-point confidence scale.

Ethics approval

The project was approved by the University of Adelaide Human Research Ethics Committee (approval H-2020-045). All users provided their consent to participate in the study (online).

Results

POCUS user survey

The survey was completed by 10 GPs, of which seven reported no previous use of POCUS in a primary care setting, eight reported completing an accredited training course at sometime within the previous 3 years, usually of less than 3 days duration (not including the training provided as part of this study). The remaining two GPs reported having some informal learning or unaccredited formal teaching.

A summary of GPs’ reported confidence in using POCUS for specific assessments and procedures is presented in Table 1. Most users reported confidence for identifying an intrauterine pregnancy (n=9), obtaining difficult intravenous access (n=9), identifying a distended bladder (n=8) or an abdominal aortic aneurysm (n=8). Fewer users reported confidence assessing symmetrical growth of the foetus (n=2), LV function (n=2), hydronephrotic kidney (n=1), and none reported confidence in the reduction of a Colles fracture. Confidence scores were comparable for those GPs with or without accredited training prior to this study.

Table 1: General practitioners’ reported confidence to use point-of-care ultrasound for specific assessments and procedures

Reported POCUS activity

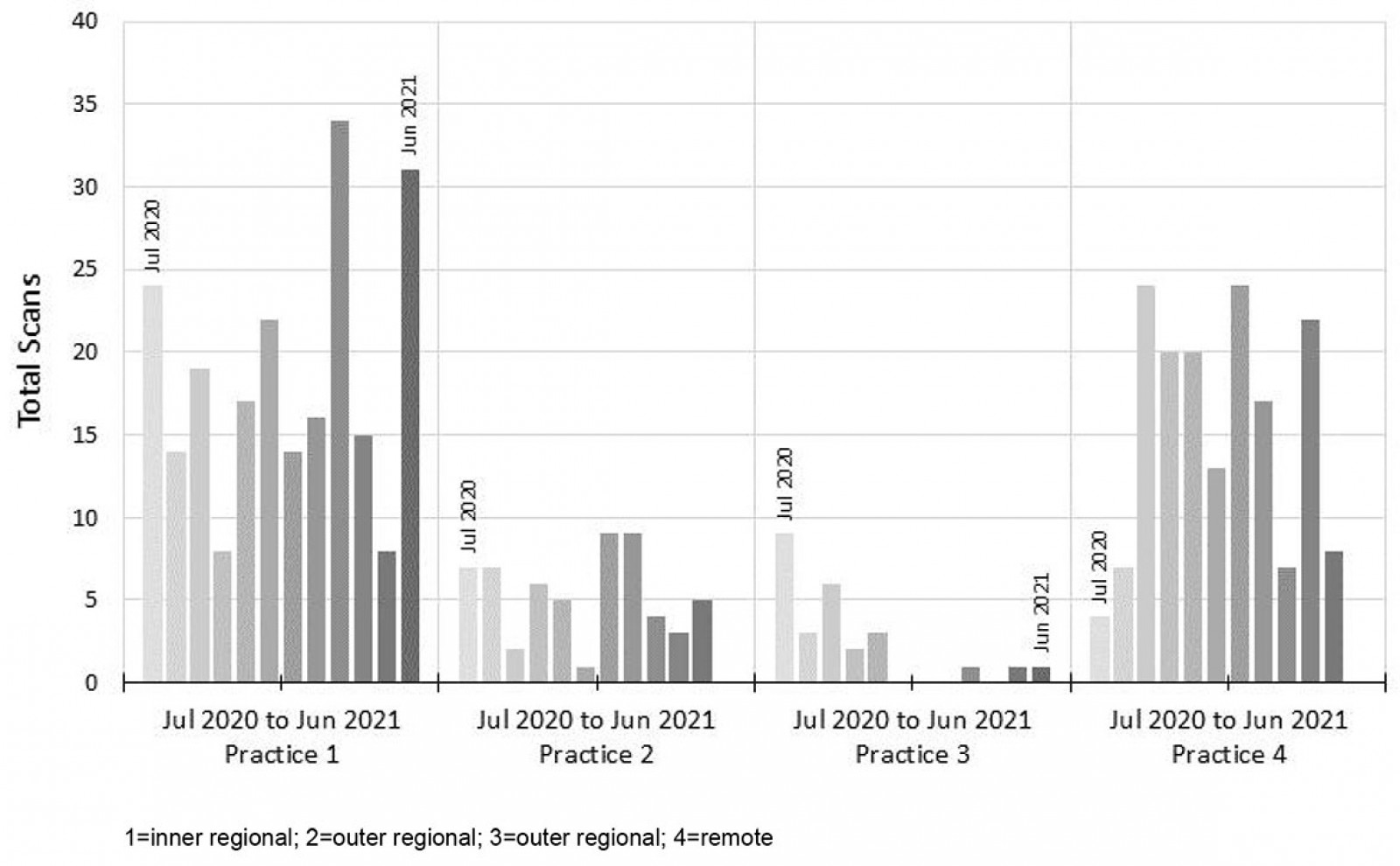

A total of 472 POCUS scans were reported during the study period from all four practices. Figure 1 shows the monthly number of reported scans from each practice. Most scans were conducted in the inner regional (47%) and the remote (35%) practices. The total monthly reported scans varied but did not show any increasing/decreasing pattern. Three GPs from separate practices were responsible for 80% of all scans. Most scans (95%) were undertaken for clinical indications, 3% for teaching and 2% for learning/self-practice.

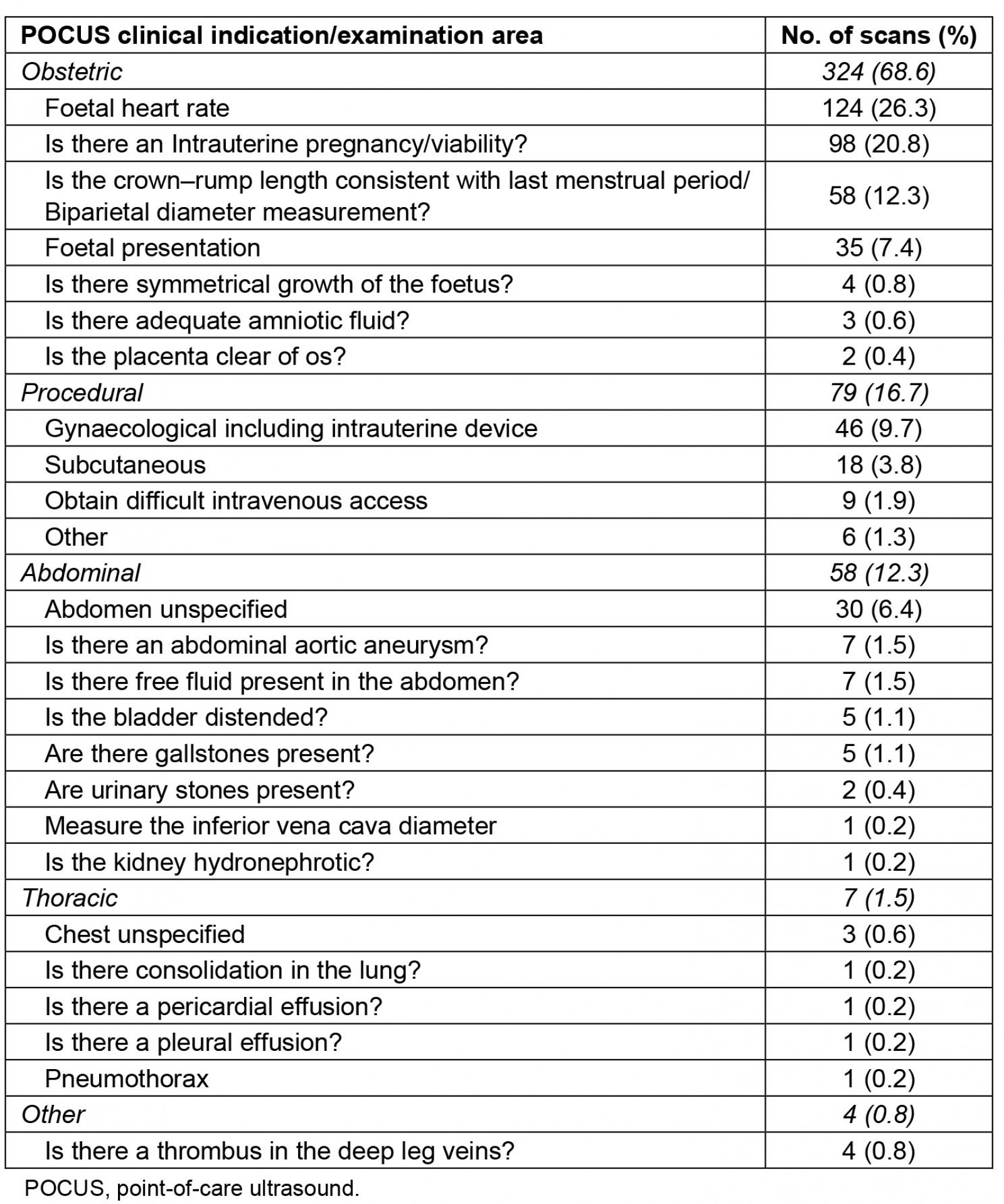

Table 2 shows that obstetric scans (68.6%) were the most commonly performed, especially for evaluating foetal heart rate and intrauterine viability, followed by procedural (16.7%) and abdominal (12.3%) scans. GPs reported using a curved probe in 439 (93%) of the scans and a straight probe for 33 (7%).

Table 2: Frequency of point-of-care ultrasound scans reported by clinical indication

Figure 1: Total point-of-care ultrasound scans per month by participating rural general practices.

Figure 1: Total point-of-care ultrasound scans per month by participating rural general practices.

Discussion

This exploratory study provides insights into POCUS applications when GPs are provided with access to training and portable equipment in Australian rural primary care. Our findings indicate high use of POCUS for obstetric scans and various procedural activities, consistent with the GPs’ reported confidence in performing these scans. Limited use for teaching or learning/self-practice was reported, despite all practices being teaching sites.

The high use for obstetric scans may reflect users’ clinical interests, limited access to formal sonographers, or obstetric patient requests/expectations12. Importantly, international studies have shown POCUS can benefit obstetric patients in rural settings, through early diagnosis, reduced travel and decreased healthcare costs9. Contrasting our findings, the scope of POCUS practised in rural hospital settings in New Zealand showed cardiac and volume scans (inferior vena cava and jugular venous pressure), gallbladder and kidney scans being most common13.

As expected, GPs reported higher confidence for lower complexity scans. Lower utilisation of POCUS for complex scans may be explained by training, as some procedures may be mastered within a few hours, while others require more extensive training14.

We observed no clear increasing/decreasing pattern in POCUS use over the study period. Possible barriers to POCUS use include time pressures on consultations, the lack of Medicare billing for POCUS, reduced visitations during COVID and limited confidence. These factors may have also contributed to the low use for teaching purposes (3%), despite all practices having a clinical academic to support medical students.

Limitations

First, the small number of POCUS users and self-selection bias (ie clinicians with special interests) may have influenced POCUS use patterns. Second, data collection only included broad description of POCUS procedure and relied upon inclusion and accuracy of user recording, as the POCUS machines did not allow direct exportation of deidentified scans to an electronic database. Third, the results were not matched to the total number of clinical encounters at each practice, or the reason for these encounters, to understand the magnitude of POCUS use in rural primary care. Finally, the study provides no information about the quality of POCUS undertaken.

Future considerations

Rural practice frequently requires clinicians to work within multiple specialist areas, such as obstetrics and/or emergency medicine, where POCUS could be beneficial13,15,16. However, rural practice costs are potentially prohibitive for POCUS in Australia due to the fee-for-service nature of general practice, the cost of high quality POCUS machines, and no additional government rebate for POCUS17-19. This study suggests that simply providing access to a portable machine and one-off training is insufficient to increase POCUS in the current GP context in rural Australia. Furthermore, as POCUS is a user-dependent technology it requires appropriate ongoing training and quality assurance. A more comprehensive program of training, reimbursement for use and access to machines may improve POCUS uptake longitudinally5.

Conclusion

Although POCUS has diverse applications in rural practice, GPs reported limited confidence for certain scans and used POCUS predominantly for obstetric indications. Further studies examining the barriers to POCUS utilisation may be beneficial, with particular consideration given to the need for regular training, reimbursement for use and access to machines.

Funding

The Adelaide Rural Clinical School is funded by the Commonwealth Department of Health, through the Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training grant.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contribution of the GPs and other practice staff who participated in this project. Our thanks also go to Dr Katrina Morgan for expert advice.