Context

Hand therapy optimises functional use of the hand and arm after injury and is an expert area of practice for occupational therapists (OTs) and physiotherapists. Hand therapy is the evaluation and treatment of injuries and conditions of the upper extremity1. Combined with generalist therapy skills of communication, professionalism and resource management, hand therapy requires specific anatomical and biomechanical knowledge, clinical reasoning and technical skills2. Accredited hand therapists are required to undertake further specialised training through a Master’s degree, the Certified Hand Therapy Exam3 or courses offered by the Australian Hand Therapy Association and must maintain 20 professional development hours each year specifically related to hand therapy practice and contribute 25 hours per 5-year period to the profession4.

In contrast, rural clinicians must demonstrate expertise, not only in hand therapy, but in several different caseloads5. Professional development opportunities in specialist clinical areas, such as hand therapy, are generally offered in urban areas and are costly to access6,7. Patients who have sustained a hand injury often receive initial hand surgery and rehabilitation in metropolitan or larger regional centres. Rural patients’ access to follow-up hand therapy after the initial phase of care can be affected by transport options, distance, staff shortages and availability of therapists skilled in hand therapy. Due to the manual nature of rural occupations, the impact of incomplete functional return of both hands after injury/surgery is significant8.

Issue

Toowoomba Hospital is a regional hospital within the Darling Downs Health Service (DDHS) in Queensland, Australia. The DDHS is divided into four clusters: Toowoomba, South Burnett, Southern and Western. The Toowoomba Hospital occupational therapy department receives over 1000 referrals for hand therapy each year, and at least 25% of these referrals are for patients who live more than 50 km from Toowoomba Hospital, herein called rural patients. At the time of the project, 14 (predominantly part-time) rural OTs across the DDHS provided follow-up for rural patients.

Between 2017 and 2019, Toowoomba Hospital orthopaedic department patient activity generated significant growth in hand therapy occasions of service for rural clusters. Allied health activity data for this period, obtained from local hospitals’ statistic databases, showed a 53% increase in occasions of service, with some rural clusters recording growth of up to 79%. After surgery, more orthopaedic outpatient reviews were offered via videoconference consultation, and patients subsequently requested hand therapy appointments at their local facility. Brief referrals were forwarded to rural therapists with minimal additional information, and handovers for ongoing care were emailed in a non-standardised way. After patients were referred to rural locations, they were discharged from Toowoomba Hospital occupational therapy. Consequently, if a rural therapist contacted the Toowoomba Hospital OT regarding a patient, the clinical history was not readily available, and if an appointment was requested for the patient then the rural therapist was required to write a new referral.

Rural therapists expressed low confidence in managing the increasing volume and complexity of hand therapy referrals. Toowoomba Hospital OTs provided ad-hoc support to rural colleagues in the context of a busy outpatient clinic. Available support mediums included telephone communication or scheduled videoconference, but there was limited uptake of the latter service. It was noted that provision of telephone advice without patient assessment posed a medico-legal risk. The existing model did not meet the needs of rural patients or therapists and, as a result, poorer clinical outcomes of hand injuries became a potential risk.

A new model was required to support rural therapists and provide service equity for rural and remote patients. This report outlines the development of a model of care for the provision of occupational therapy to rural patients who have sustained a hand injury and/or undergone hand surgery.

An application for a Not Requiring Ethical Review letter for a quality activity was made to the Darling Downs Hospital and Health Service ethics committee and approved on the 3 July 2019 (Reference number LNR/2019/QTDD/55524).

In July 2019, two part-time advanced OTs, who are also accredited hand therapists, were employed as clinical leads to conduct a service evaluation. A literature review was conducted and an experienced researcher on hand therapy service provision for rural patients consented to mentor the project. The main components of the service evaluation included a survey of rural therapists and a service mapping activity. Feedback from orthopaedic surgeons was also obtained and a patient survey was planned; however, service changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic meant the survey had to be abandoned after only seven responses.

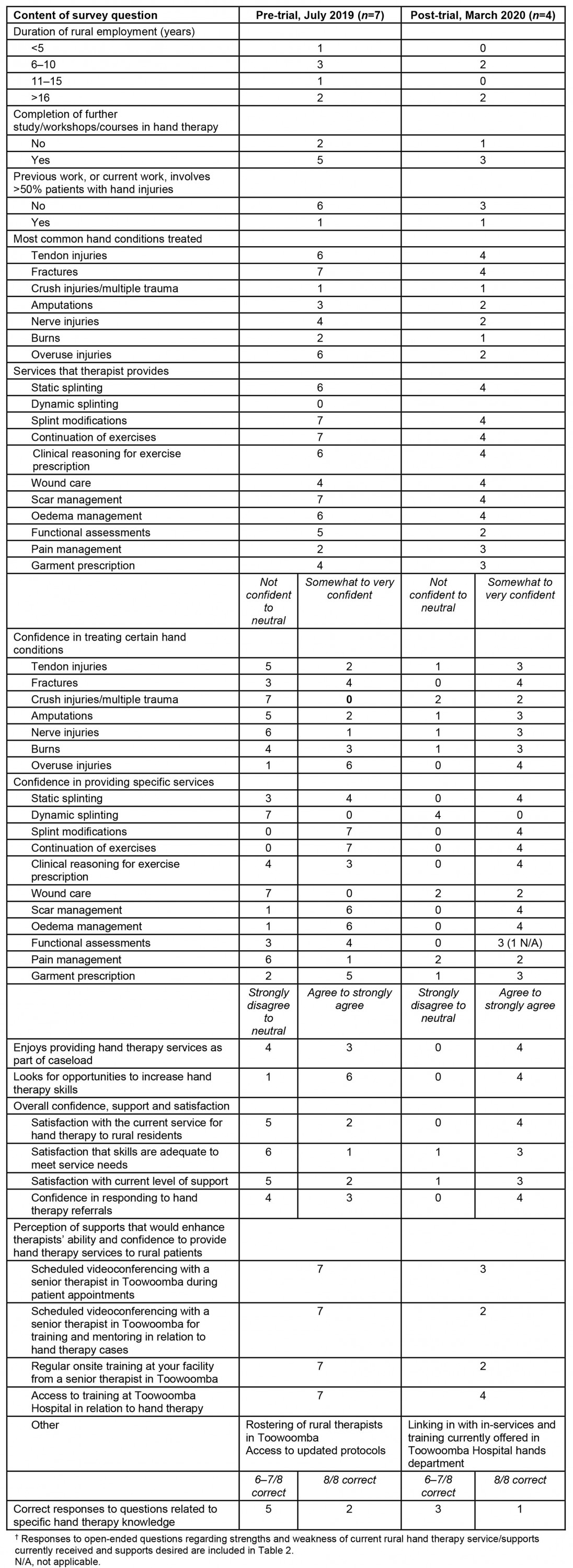

The rural OT survey included questions about the duration of rural practice, hand therapy experience and current caseload, confidence, perception of strengths and weaknesses of current local and regional hand therapy service, and clinical knowledge. In July 2019, an email was sent to 14 rural DDH OTs, inviting them to complete an anonymous survey via Survey Monkey. Results from the seven responses are summarised in Tables 1 and 2.

The clinical leads visited the rural sites during the service mapping activity to gather information on referral processes, booking systems, resources, training needs, allied health assistant support, and the structure of generalist OTs’ caseload. Feedback from discussions with Toowoomba Hospital orthopaedic doctors confirmed the need for change to the service delivery model and support for an alternative model of care.

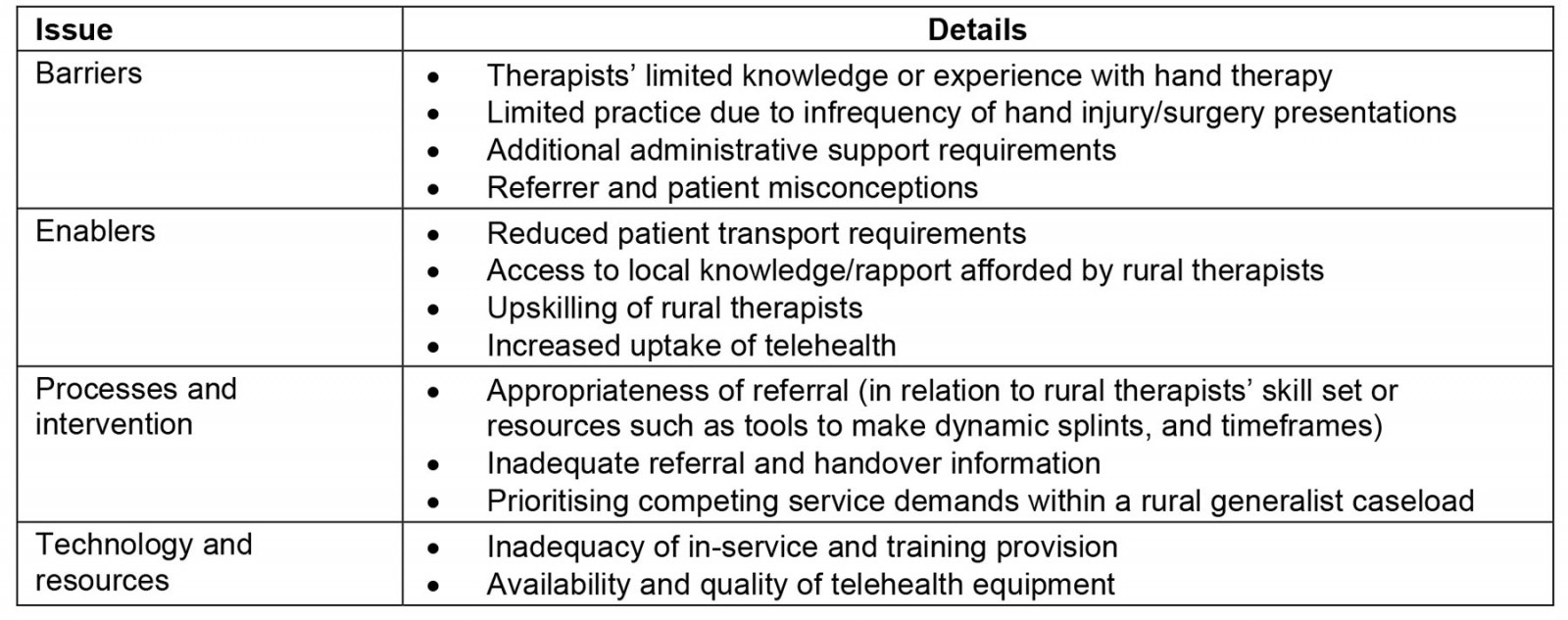

Information from the mapping activity and rural therapist survey were grouped into themes, and four core issues were identified: barriers, enablers, processes and intervention, and technology and resources, as outlined in Table 2.

Table 1: Pre- and post-trial rural occupational therapist survey data†

Table 2: Core issues identified in the service evaluation

Development and implementation of the new model of care

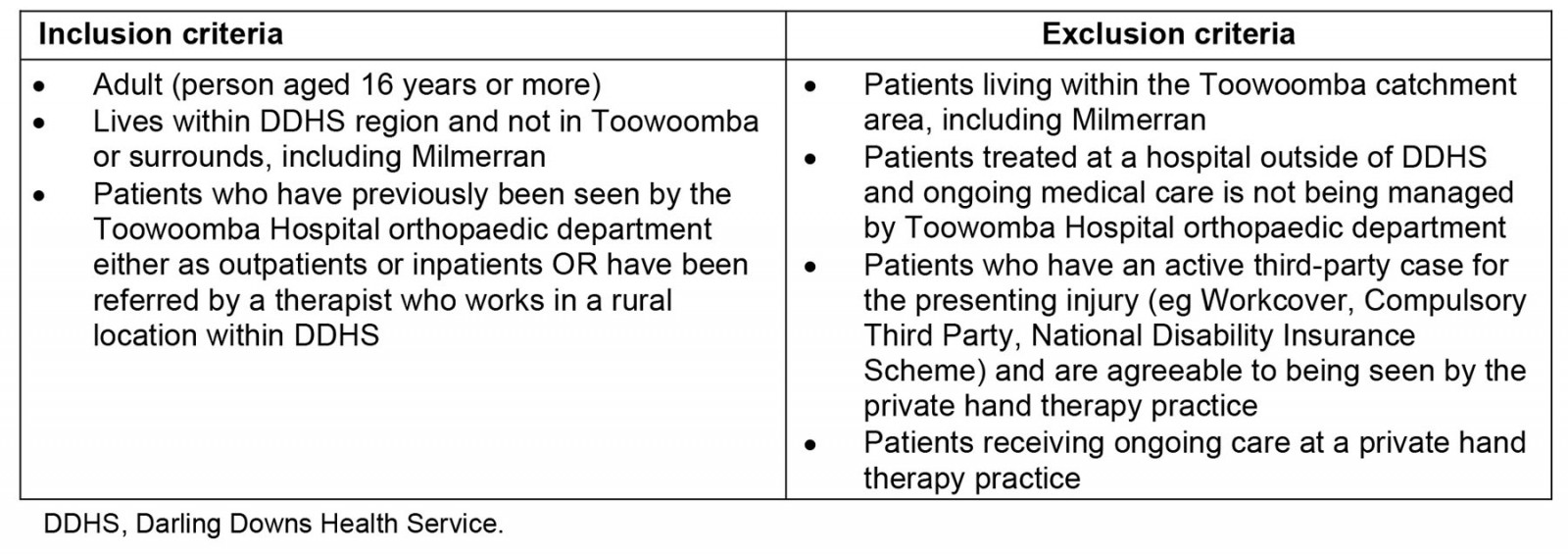

Utilising the results from the service evaluation, the RHTP model of care was developed from September to November 2019. The model is a ‘shared care approach’ that provides optimal care through ‘a range of frequent, flexible, accessible and reliable communication strategies’8 between the clinical leads and rural therapists in the DDHS. Table 3 outlines the inclusion and exclusion criteria for referral to the RHTP. To minimise medico-legal risk, patients who were treated at a hospital or practice outside of the DDHS and had an experienced OT to provide clinical advice were not included in the project. The criteria also aimed to capture patients who were referred to rural therapists by GPs.

A clinical lead in Toowoomba saw eligible rural patients with complex injuries/conditions for their initial appointment. This attempted to address therapists’ concerns regarding skillset and presentation complexity. Familiarity with these patients with complex hand injuries reduced medico-legal risk associated with the lead clinician later providing advice on ongoing patient care. Referrals were accompanied by doctor outpatient notes (if required to fully understand a patient’s history) and initial triaging by the lead clinician with a timeline for initial review. An email proforma was created to ensure detailed handover of patients initially seen at Toowoomba Hospital. These changes enabled more efficient communication between sites, which in turn reduced the risk of delayed or inappropriate treatment. The new service delivery model ensured that all rural patient cases remained open at Toowoomba Hospital for a minimum of 3 months, allowing patients to be seen by the clinical lead as needed. Appointments were available for initial assessment or review by the local therapist with the clinical lead present via telehealth. Furthermore, a rural therapist or patient could request a review appointment in Toowoomba for complex splinting or face-to-face shared care.

The lead clinician became the consistent main contact for any clinical questions regarding hand therapy practice or individual patient care from rural therapists. This led to greater continuity of information and uniform patient care. Weekly or fortnightly case conferences for all rural clusters were introduced. The rural therapist decided on the format of the case conference, and all open cases or cases of note were discussed. This allowed for timely identification of issues, verbal handover and context-specific education. The final component of the RHTP was for the lead clinician to provide targeted support and education to rural therapists. The aim was to increase the capability and skills of the rural OTs to provide hand therapy services in rural locations.

The project was scheduled to run from 1 July 2019 to 30 June 2020, with the trial phase from 1 December 2019 to 31 May 2020. However, due to service changes related to the COVID-19 pandemic, the trial phase of the project ceased on 31 March 2020.

Table 3: Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the Rural Hand Therapy Project

Lessons learned

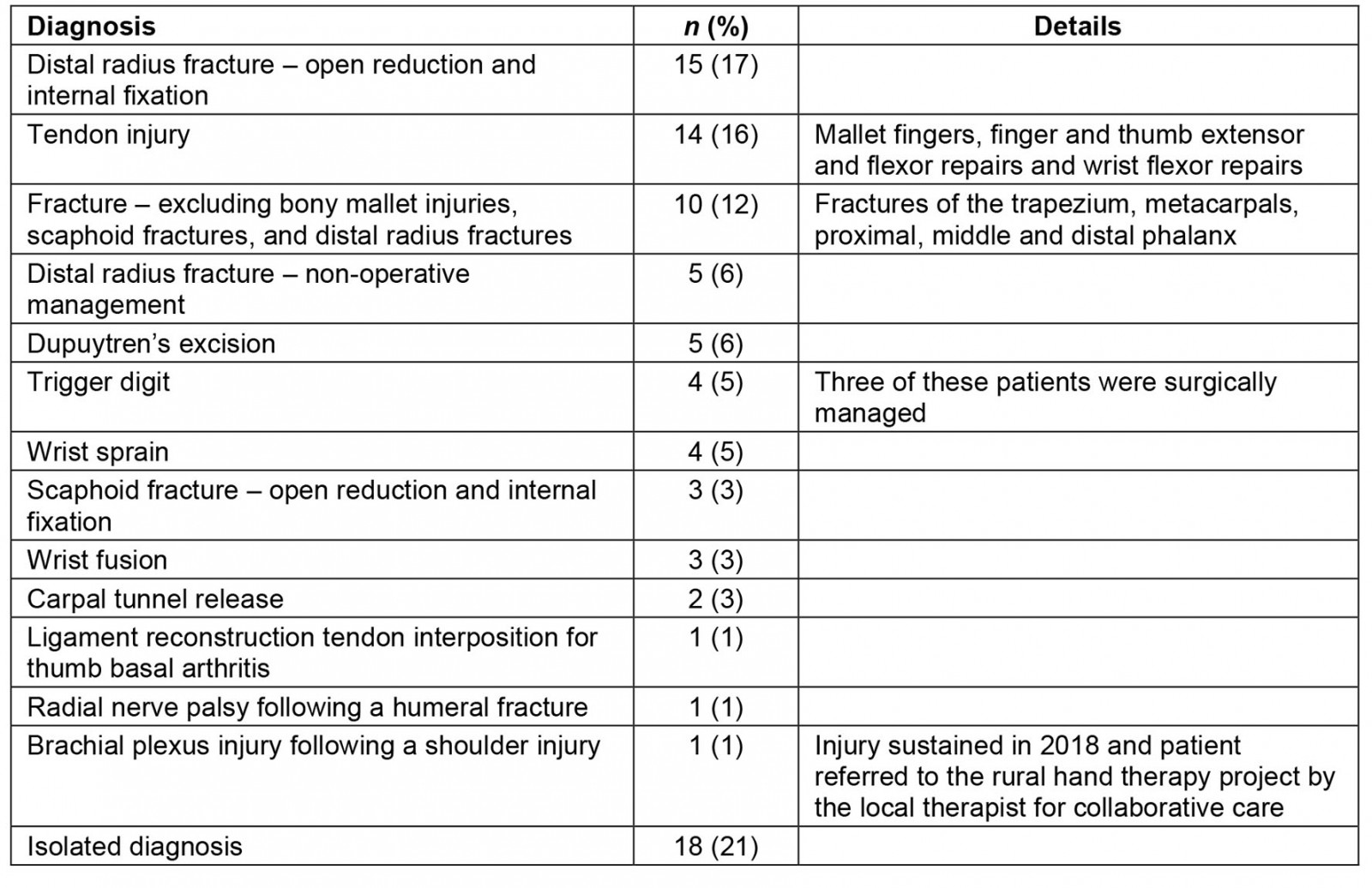

During the trial phase, from 1 December 2019 to 31 March 2020, the OT department at Toowoomba Hospital received referrals for 343 patients aged 16 years or more who had sustained a hand injury. Eighty-seven patients lived in one of the rural clusters, at least 50 km from Toowoomba. At the time of the chart review, one of these patients was deceased and the chart was not available for inclusion. Thirty-seven patients lived in the South Burnett cluster, 25 lived in the Western cluster and 24 patients lived in the Southern cluster. Table 4 details the diagnosis that resulted in rural patients’ referral to hand therapy.

Of the 87 rural patients who received hand therapy during the trial phase, the RHTP clinical leads were involved in both initial assessment and ongoing intervention for 48 patients (56%). This included requests from the local therapist for a collaborative clinical lead review via videoconference, support via email or a face-to-face review after a patient’s orthopaedic review and subsequent handover. Two clusters commenced weekly case conferences, which involved discussion of active referrals. The commencement of the RHTP led to a notable increase in the provision of videoconference occasions of service. In the same 3-month period in the preceding year, only 1% of occasions of service were via videoconference, whereas during the trial period videoconference occasions of service increased to 8%.

After the early cessation of the trial, the self-reported therapist survey was repeated, and four responses were received, as shown in Table 1. Data collection during the trial phase was limited due to staffing and COVID-related service issues. Research has commenced to determine the impact of the new model of care on patient outcomes, equity and acceptability.

The evolution of a model of care is an iterative process9. Clear criteria were initially required to give a foundation to the new model of care. Improvements in the flexibility of service delivery have made redundant the initial criterion that ‘all eligible rural patients with complex injuries/conditions were seen for their initial appointment at Toowoomba’. Now, rural therapists are consulted to determine whether a patient should initially be seen in Toowoomba or locally.

Retention issues in the rural allied health workforce can negatively impact patient care and place additional strain on remaining staff10. One positive outcome of the RHTP was the flexibility to respond temporarily during rural staff crises and provide essential patient care. From November 2020 to February 2021, staffing shortages affected a subregion where 34% of all occupational therapy referrals were for hand therapy. The RHTP ensured continuity of care and patient safety by two methods. First, the local allied health assistant was trained by a clinical lead to assist with videoconferencing clinics run by a clinical lead. In the 4-month period, 33 occasions of service were provided by the clinical lead via these clinics. This approach not only ensured continuity of care and patient safety but also equipped the allied health assistant with new work-ready skills. Second, patients willing to travel were offered ongoing hand therapy treatment at Toowoomba Hospital. During this period, 44 occasions of service (5 by videoconference, 39 face-to-face) were provided to patients in this subregion at Toowoomba Hospital.

The RHTP was developed to meet the needs of rural patients with hand injuries and their treating therapists. Through a process of service evaluation, literature review and translation of knowledge into practice, an alternative model of care has been developed. Survey data, chart review and anecdotal evidence indicate that the aims of the project are being achieved. Further research is being conducted to evaluate the model, and it is hoped that, in sharing the RHTP model, health services worldwide will implement the principles outlined in this service model to improve rural/remote patient outcomes.

Table 4: Reasons for referral to hand therapy, Toowomba Hospital, Queensland Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Vilma Girardi and Marguerite Bennetts who championed the development of the project and ensured its ongoing funding. Thanks to Anna Tynan, who guided the development of the service evaluation outcome measures and assisted with our research questions. Thanks to Dr Shridhar (Director Orthopaedics TH) for supporting the implementation of the project and ensuring collaboration between doctors and OTs to enable quality patient care. Thanks to each DDH OT who provided hand therapy to patients involved in the project.

References

You might also be interested in:

2011 - Barriers to the up-take of telemedicine in Australia - a view from providers

2009 - Pandemic influenza containment and the cultural and social context of Indigenous communities