Introduction

Kowanyama is a very remote Aboriginal community in the Torres and Cape Hospital and Health Service (TCHHS) region on the Cape York Peninsula in Far North Queensland, Australia. It has some of the poorest health outcomes in Queensland. The life expectancy in TCHHS is on average 24 years less than for the rest of Queensland, with the highest rate of preventable hospitalisations out of 15 hospital and health services in Queensland1.

Kowanyama scores extremely low on the Socioeconomic Index for Areas: it is in the lowest 1% of communities in terms of advantage2,3.

Health services are supplied to the community by Queensland Health (QH), Apunipima Cape York Health Council and the Royal Flying Doctor Service (RFDS). QH manages Kowanyama Primary Health Care Centre, which is staffed by full-time Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander Health Workers and registered nurses. There are visiting GP services 2.5 days each week for a population of around 12004. The healthcare centre has most of the characteristics of remote Indigenous community sites: serving a small population in remote and very remote locations, often staffed by one or a small number of registered nurses and community healthworkers, and interventions are often provided using remote phone consultation or telemedicine link5. The health centre has a treatment room but no observation beds or provision for overnight stays. RFDS provides GP services, with two doctors flying in late in the morning each Tuesday and departing early each Thursday afternoon. On-call is provided by the remote area nurses, who liaise with an offsite doctor by phone 7 days a week after hours and on the 5 days that there are no visiting GPs. Administration staff vary in availability and QH nursing staff are often supplied by locum agencies. There are also a range of fly-in fly-out specialist, allied health and mental health services when available6.

Aeromedical retrieval services in Australia have evolved to meet the challenges of providing care to isolated remote and rural communities across a vast country with a low population density7-10. In one study, 6% of retrievals over a 12-year period for RFDS Queensland were for critically ill patients. In another 14.9% were for priority 1 (highest acuity) cases5,8. The majority of retrievals are usually for priority 4 (semi-urgent) cases5.

All retrievals from this site are referred to as modified primary retrievals, where a patient has been taken from a healthcare site with minimal capacity to increase the level of care that is provided from the pre-hospital environment such as the Kowanyama Primary Health Care Centre5.

Regional and remote hospitals have high rates of admission for conditions that could be managed in the community (potentially preventable hospitalisations, PPH). PPH rates are used as a measure of timely access to quality primary health care11,12.

The present audit was conducted to:

- determine the number and type of retrievals and subsequent hospital admissions in a 1-year period from a single remote Cape York community

- determine if these retrievals might have been preventable with access to a full-time, on-site GP service in a GP-led primary health care (GPLPHC) model

- analyse the cost difference of preventable retrievals compared to providing a full-time, on-site GP-led service in this community13.

Methods

This was a retrospective clinical audit of charts with convenience sampling. A sample size of 89 was calculated to give a confidence level of 95% and confidence interval (CI) of 1014.

Cases were identified and data obtained from local clinic records of retrievals undertaken. They were correlated with patient medical records and transfer notes, and included if they involved aeromedical retrieval from Kowanyama from 1 January 2019 to 31 December 2019, inclusive.

The information on each retrieval was examined by a remote nurse or GP. Using an audit tool made by the authors, the management and reason for evacuation were assessed against Queensland Health’s Primary Clinical Care Manual guidelines, and whether the presence of a rural generalist GP would have prevented the need for retrieval15. Each retrieval was also assessed against accepted Australian criteria for potentially preventable hospital admissions with the addition of two Canadian criteria to determine if it was ‘preventable’ or 'not preventable’16-19. Canadian criteria included non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction and sepsis, which were included because cardiology was the most common or second most common retrieval reason in various studies in this region, cardiovascular disease is the most common cause of death among Indigenous Australians, and sepsis is also a common cause of retrieval and common cause of mortality in remote areas5,17,20,21.

A cost analysis compared the cost of providing benchmark levels of GPs in community with the cost of potentially preventable retrievals.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from Queensland Health (LNR/2019/QCH/55214-1364 QA; project ID 55214).

Results

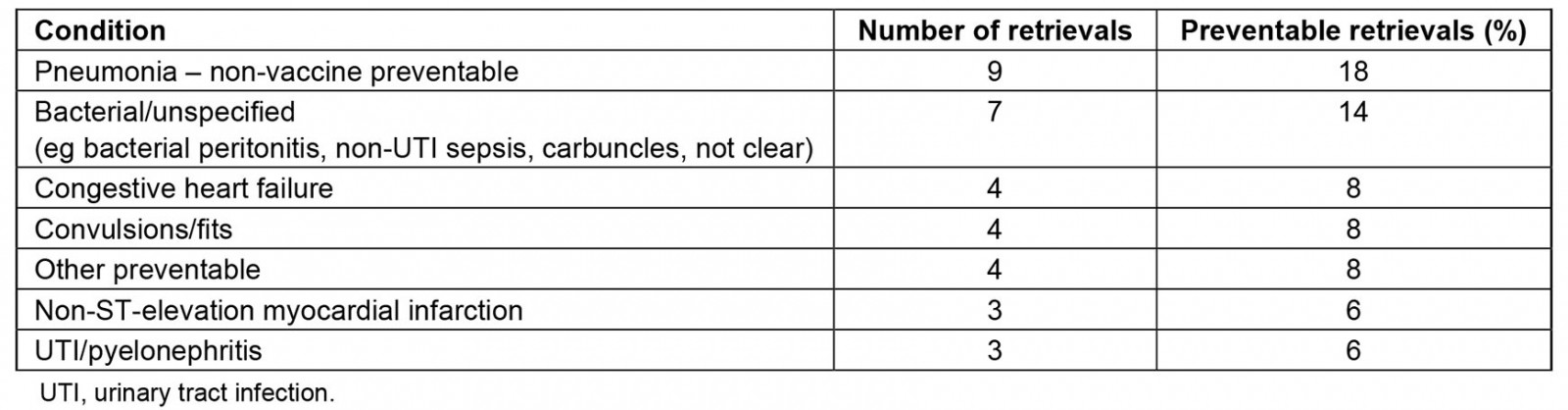

There were 89 retrievals of 73 patients in 2019. Thirty-nine percent (35) of all retrievals occurred when a doctor was on site. Thirty-three percent (18) of preventable retrievals occurred with a doctor on site and 67% (36) of preventable retrievals occurred with no doctor on site. Sixty-one percent (54) of all retrievals were potentially preventable (Table 1).

Non-preventable retrieval reasons consisted of (in order) assault/trauma needing intervention psychiatric, urolithiasis, assault/trauma needing imaging, abdominal pain unknown, cholecystitis, cerebrovascular accident, pulmonary emboli, slipped upper femoral epiphysis/synovitis, atrial fibrillation, appendicitis, bradycardia, low calcium, haematemesis and pancreatitis.

There were 78% (69) of retrievals admitted to hospital, 1% (1) deceased, 10% (9) discharged without admission and 11% (10) with an unknown outcome. A paucity of information on patient outcomes was noted in this study and has also been noted in other similar studies5. All retrievals with a doctor on site resulted in an admission to hospital. All immediate discharges or deaths were for retrievals without a doctor on site. At least 30% (27) of all retrievals had at least one escort.

For preventable-condition retrievals, the mean number of visits to the clinic in the 4 weeks preceding retrieval compared to non-preventable condition retrievals was higher for registered nurse or Aboriginal Health Worker visits (1.24 v 0.93) and lower for doctor visits (0.22 vs 0.37). This means that patients flown out for potentially preventable conditions had fewer doctor visits but more registered nurse or Aboriginal Health Worker visits.

Table 1: Conditions classified as preventable retrievals

High-frequency retrievals

Some patients used the retrieval system several times: 32% (20) of patients accounted for 52% (46) of retrievals and of these 63% (29) were potentially preventable (as compared to 61% overall). Of these 20 patients, three had more than two retrievals.

Cost analysis

The very conservatively calculated minimum costs of potentially preventable retrievals for 2019 was A$817,936. The costs for interhospital transfers were based on A$2912 per engine hour, which includes an RFDS registered nurse. For transfers in which an RFDS medical officer is also required, an additional A$2223 per hour could be added to the cost of each interhospital transfer, but this information was not available so the cost is likely underestimated. This formula is consistent with other published literature22,23.

National hospital cost data collection24 was used to estimate the costs of hospitalisations. Patient Travel Service data and airline information were used to estimate travel and patient escort costs25.

The calculated maximum cost of providing benchmark numbers (2.6 full-time equivalents) of rural generalist GPs in a rotating model was A$945,493. This was based on salary, cost, travel and accommodation figures provided by Queensland Health24-28. It does not include other potentially considerable savings such as Medicare Benefits Schedule billings and salary support for GP registrars.

Discussion

Regional and remote hospitals have high rates of admission for conditions leading to PPH that could be managed in the community with timely access to a quality primary health service11,29. The reason people living in regional and remote areas have higher PPH rates is a complex issue, but difficulty accessing quality primary health care is accepted as a contributing factor16,19,20,30,31. PPH rates are used as a measure of timely access to quality primary health care, and factors such as adequate doctor supply, long-term doctor–patient relationships and GP management plans have all been found to be important for reducing PPHs and investment in primary healthcare services has been shown to significantly reduce the associated costs11,29.

This audit reveals that having full-time GPLPHC in a remote Indigenous community may prevent the aeromedical retrieval of some patients to an acute care hospital. Nurse practitioners are not utilised in remote communities in Cape York and there is limited data to compare nurse-practitioner-led primary health care with GPLPHC, so this analysis is based on GPLPHC and the related evidence11,19,32,33.

Access to disease prevention and management services, the majority of which are provided by GPs, has been shown to reduce aeromedical retrievals for acute care. In one study, aeromedical retrievals for acute care for renal disease were much higher in areas without regular access to renal disease prevention or management services34. A study in 2009 found that most frequent users of a retrieval service in rural New South Wales, Australia, had complex chronic disease that would have benefited from multidisciplinary care or shared specialist care, and suggested that they may have unmet health needs and poorly managed disease of the sort usually managed in general practice35. Also, they are less likely to have a GP management plan and more likely to have had infrequent clinic reviews. Factors affecting clinic attendance include access, economic and cultural factors36. This audit showed that those with high-frequency and potentially preventable retrievals had higher clinic attendance than those with non-preventable retrievals, but lower numbers of GP visits, suggesting that GP-led care as opposed to clinic attendance is the influencing factor. This is consistent with evidence published to date and aligns with evidence globally suggesting that access to GPLPHC improves outcomes and equity for the community11,16,29,36-38. Other issues in this setting that can affect care outcomes are poor continuity of care from several primary care providers from different organisations. This potentially contributes to increased hospital use, as demonstrated in several reviews and studies36,39,40.

For Indigenous patients, who constitute most patients in the subject community, there are additional health, social and cultural benefits to being able to be managed effectively in their community and not being retrieved to a major centre unnecessarily, which causes disruption to patients and their families41.

While retrievals for ASCS/PPH are assumed to be a measure of poor access to primary health care, a doctor on site at time of retrieval was related to fewer preventable condition retrievals. This suggests the on-site emergency treatment provided by rural general GPs could be an additional benefit of having a doctor continuously in the community, but supportive evidence elsewhere for this is lacking.

Admissions to Cairns Base Hospital (the largest hospital in Far North Queensland) as an outcome were similar if a doctor was on site or not. After a patient is transferred to Cairns by RFDS an admission is usually mandated, especially if a patient comes in late at night. The patient may be discharged the next day but is still recorded as an admission. All discharges and deaths were for retrievals without a doctor on-site, suggesting a doctor on site may prevent unnecessary retrievals.

One study found that withdrawal of GP services from a remote community let to an immediate and sustained doubling in aeromedical retrievals. The reintroduction of these services some years later did not immediately reverse this trend, which lends caution to expectations about the timeline over which improved GPLPHC access can reduce retrieval rates42.

Access to primary care physicians and primary health care has been shown in many jurisdictions to be cost-effective and provide cost savings to the health budget37,43-45. We estimate the cost of providing 2.6 full-time equivalent rural generalist GP coverage to the community of Kowanyama is comparable to the costs of evacuations for preventable conditions. Given the conservative stance taken on cost calculations and the lack of currency for the figures used, it would be expected that the actual costs of retrievals could be considerably higher than the costs of rural generalist GP coverage for communities like Kowanyama. If some of the doctors were rural general GP registrars (doctors in training) then the cost saving would be even greater, because trainees have access to salary support46. Also, potential Medicare Benefits Schedule billings were not included.

Ideally, all Australians should have access to appropriate primary health care to ensure good health. There needs to be a better understanding of other factors that impact patient outcomes in remote communities, such as the social, economic and personal impacts of aeromedical retrievals in rural and remote populations, and the need for better integrated multidisciplinary care, continuity of care, cultural competency in healthcare providers and care being provided on country – but some of this is outside the scope of this article20,36,40,47,48.

Limitations and assumptions

Records of retrievals may not be accurate and the Retrieval Services Queensland database has limited data. Clinic records were often incomplete or missing information.

Assumptions were made that clinical diagnosis was correct and consistently defined by clinicians. Underlying conditions were not always recorded (eg cellulitis could be secondary to chronic diabetes).

Conclusion

The findings of this audit suggest that having a full-time rural generalist GP presence in communities like Kowanyama within a GPLPHC model of care has the potential to reduce rates of retrieval for preventable conditions, and thus financial cost to the health budget, and potentially improved patient outcomes.

It is recommended that a fully resourced audit and full review be conducted at Kowanyama to support a business case proposal for a full-time medical presence in community.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Helen Hewitt, Director of Nursing, Kowanyama Primary Health Care Centre, Torres and Cape Hospital and Health Service.

References

You might also be interested in:

2022 - COVID-19 impact on New Zealand general practice: rural–urban differences

2016 - What is a sustainable remote health workforce? People, practice and place

2005 - Rabies surveillance in the rural population of Cluj County, Romania