Introduction

The broad definition of oral health is being able to speak, smile, smell, taste, touch, chew, swallow, and emote with facial expressions without pain, discomfort, and disease of the craniofacial complex1,2. Among the oral conditions impacting oral health is tooth loss, the ‘endpoint of a lifetime of dental disease’3. Tooth loss is a critical healthcare concern and indicator of oral health commonly associated with dental caries and periodontal disease3,4. There were 3.5%, or 267 million people worldwide with complete tooth loss (edentulism) in 20175. In the USA, 12.9% of adults, aged 65 years or more, were edentulous6. For US adults aged 18–40 years, 23.3% of males and 25.2% of females had lost at least one tooth (p<0.001)7. Tooth loss is associated with lower income4,8, education level9, race/ethnicity10, previous tooth loss, dental caries, seeking dental care for pain11, age, employment, home ownership12, diabetes, interleukin-1 polymorphism, smoking, bone loss, dental pocket depth, tooth type, furcation involvement, mobility, and endodontic involvement13.

Tooth loss affects appearance, with potential secondary effects on employment/job advancement14, social isolation/embarrassment, poor self-esteem15, and mental health. It affects chewing ability and thereby physical health. With an increasing number of missing teeth, there is a decrease in chewing function and there are potential decreases in fiber intake, inadequate dietary nutrient intake, and lower adherence to the US Department of Agriculture Dietary Guidelines16. It has been associated with chronic and often debilitating diseases such as cardiovascular disease17, asthma and congestive obstructive pulmonary disease18, diabetes19,20, and Alzheimer’s disease21.

In a US prediction study using 2008 data, Indigenous people (American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) adults) had the highest predicated rate of edentulism (24.0%) as compared with African American adults (19.4%), Caucasian adults (16.9%), Asian adults (14.2%), and Hispanic adults (14.2%)10. AI/AN adults have many oral health disparities, limited access to dental care, and long travel distances to dental care22. The impact of lived experience in a rural versus urban setting or in different regions of the USA has not been recently examined for association with dental visits or missing teeth among AI/AN adults.

The aim of this research was to determine if there is a difference in dental visits or missing teeth among adult AI/AN adults who live in rural settings versus AI/AN adults who live in urban settings. The second aim was to determine if there is a difference in dental visits or missing teeth among adult AI/AN adults by geographic region of the USA (Northeast, South, Midwest, or West).

Methods

Study design

This study had a cross-sectional study design.

Data source and sample

The data source for this research was the 2020 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) 2020. BRFSS is a national, cross-sectional telephone survey of US residents. It began in 1984 and comprises yearly surveys of residents’ health-related risk behaviors, chronic conditions and preventive service use. BRFSS is sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, other CDC centers, and several federal agencies23. The eligible sample from BRFSS for this study included participants who reported being AI/AN adults and had complete data on sex, rural/urban status, dental visit within the previous year (2019), and number of missing teeth (n=6640).

Measures

Dependent variables: Two dependent variables were examined. The BRFSS question and BRFSS categories for self-reported tooth loss were used (BRFSS options for number of teeth missing as none, 1–5, 6–

Independent variable: Two independent variables – region of the US (Northeast, Midwest, South, West) and rural/urban status – were examined. The following states were included for the Northeast: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont. The following states were included for the Midwest: Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin. These states were included for the South: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia (and Washington, DC), and West Virginia. These states were considered as the West: Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming; also included were Alaska and Hawaii. Rural/urban status was a provided derived variable from the BRFSS survey based upon the National Center for Health Statistics Urban–Rural Classification Scheme for Counties.

Covariates: Included in the study were several sociodemographic variables: sex (male; female), age in years (18–<40, 40–<50, 50–<60, 60–<64, ≥65), education (less than high school, high school graduate, some college and above), health insurance (yes, no), smoking (current, former, never), and income in US$ (<$25,000 (~A$37,000), $25,000–<$50,000, $50,000–<$75,000, ≥$75,000 (~A$111,200)).

Data analysis

Data were analyzed with SAS Analytics Software v9.4 (SAS Institute; http://www.sas.com). Rao Scott χ2 analyses for complex study designs with weights were completed for the variables of interest against tooth loss and dental visit. Weighted survey logistic regression was completed for unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios. A p-value of <0.05 was determined a priori as the significance level for the results.

Ethics approval

The research received acknowledgement as non-human subject research by the West Virginia University Institutional Review Board (2111472366).

Results

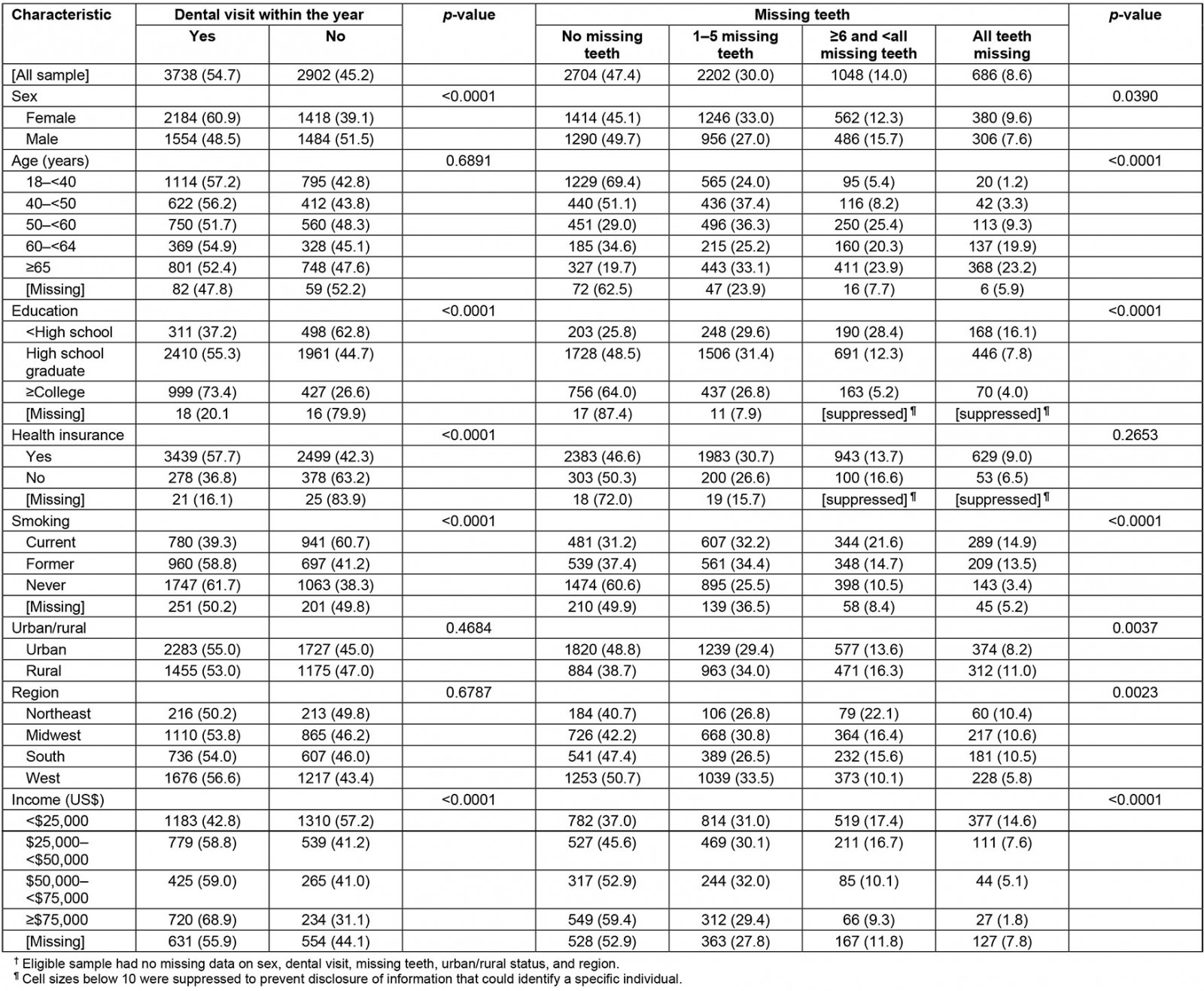

Table 1 includes the sample characteristics, bivariate associations of variable of interest with having had or not having had a dental visit within the previous year, and associations of variables of interest with missing teeth. There were 6640 participants of whom 3738 (54.7%) had a dental visit within the previous year. There were 3936 (52.6%) who had at least one missing tooth.

Among the females, 2184 (60.9%) had a dental visit within the previous year. There were 1554 (48.5%) of males who had a dental visit within the previous year. Females were more likely to have had a dental visit within the previous year, in bivariate analyses (p<0.0001).

In terms of missing teeth, among females 2188 (54.9%) had one or more missing teeth while among males 1748 (50.3%) had one or more missing teeth (p=0.0390). There were 686 (8.6%) who were edentulous, of whom 380 were female.

Significant associations with having a dental visit within the year also included higher education, having health insurance, never smoking, and higher income. The key variables, urban/rural residence and region failed to be significantly associated with dental visit.

There were several significant associations with missing teeth. These included age, education, smoking, urban/rural residence and region. AI/AN adults who were of older age, had less education, smoked, lived in a rural setting, lived in the Northeast, or had lower income were more likely to have missing teeth.

In the logistic regression analyses comparing rural and urban, dental visits (modeling no visits within the year) were similar (unadjusted odds ratio (UOR)=1.08; 95%CI: 0.87–1.36; p=0.4669). In the logistic regression comparing US regions with the West, dental visits (modeling no visits within the year) were similar (UORNortheast=0.78; 95%CI: 0.49–1.22; p=0.2721; UORMidwest=0.89; 95%CI: 0.65–1.23; p=0.4842; UORSouth=0.90; 95%CI: 0.67–1.22; p=0.4985). (Data not shown.)

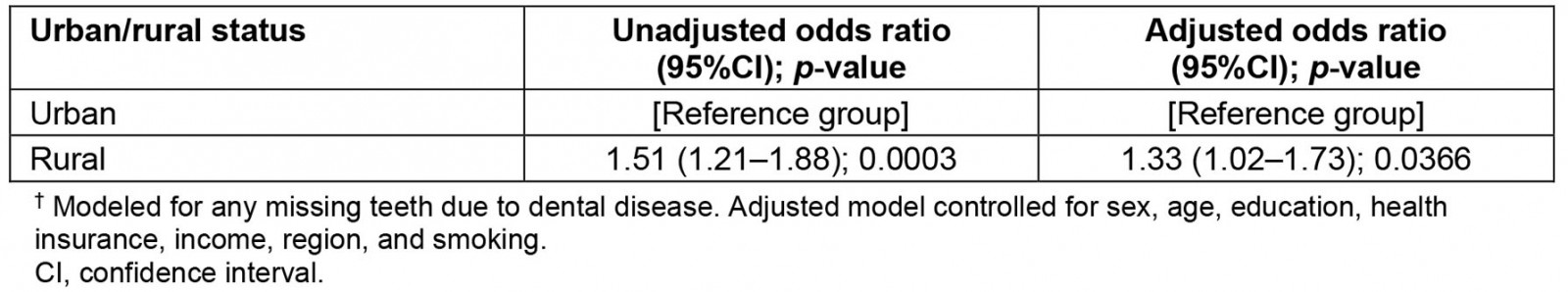

Table 2 shows the logistic regression analyses of urban/rural status on any missing teeth. The reference group was AI/AN adults who were urban dwellers. The UOR for rural areas was 1.51 (95%CI: 1.21–1.88; p=0.0003). In adjusted analysis, AOR=1.33 (95%CI: 1.02–1.73; p=0.0366).

Table 1: Native American and Alaska Native dental outcomes by various factors, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2020 (n=6640)†

Table 2: Logistic regression of urban/rural status on missing teeth†, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2020

Discussion

Among adult AI/AN adults with rural or urban status, the difference for attending dental visits within the previous year failed to reach significance. Rural and urban adults had similar levels of dental visits in 2019. Also, AI/AN adults in different geographic regions (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West) had similar attendance in dental visits within the previous year. There were differences in the number of missing teeth between AI/AN adults who lived in rural areas and AI/AN adults who lived in urban areas. AI/AN adults from rural residences were more likely to have missing teeth than AI/AN adults in urban areas.

There are few studies of AI/AN adults available to compare and contrast the dental utilization results of this study, and even fewer that are current. Most available studies of AI/AN people involve children’s dental service utilization and disparities associated with access for care for children24. In one that did involve adults, 2002–2018 BRFSS data were used. The researchers found 71% of AI/AN adults, ages 50–64 years, had dental visits within the previous year24. The data for the other age groups were presented graphically and were less than 71%. In another study of AI/AN older adults, in which the researchers used 2014–2017 National Resource Center of Native American Aging data of adults, aged ≥55 years, there were 56.5% who had dental visits within the previous year25. The results from the present study (54.7%) differ in that they reflect the ages ≥18 years, rather than >55 years, although the prevalence proportions determined in both studies are similar.

Historically, dental services to AI/AN peoples began in the United States Indian Health Service (IHS) in 1913 with five itinerant dentists26. In 1932, school-based dental services began to be organized, and by the 1950s permanent health facilities were built26. There was a shift in emphasis to greater prevention (fluoridation, pit and fissure sealants, etc.) by the 1980s; however, the prevalence of dental caries in AI/AN people has remained high26. Many AI/AN adults and children do not have easy access to dental care due to few dental service units, distance/isolation in accessing care, time away from work/family to access care, dependence upon others to travel for care, and finances. These ongoing barriers often result in delays for care, and pain. When care is delayed, restorative options may no longer be feasible. Also, if subsequent visits are needed to care for a tooth versus extracting a tooth, the time/distance barriers may influence having the tooth extracted rather than restored.

The author of the present study conducted a search of PubMed and Google Scholar for studies published within the previous 5 years concerning adult tooth loss among AI/AN adults and did not find such studies with which to compare this research. The search terms ‘American Indian Alaska Native’, ‘tooth loss’, and ‘edentulism’ were used. This is the first such study, to the author’s knowledge, that examines place of residence and tooth loss in AI/AN adults.

There are challenges to providing required dental care that will mitigate the need for extractions and further tooth loss. Dental caries is the primary cause of tooth loss; therefore, early intervention of cavitated lesions is recommended. If dental caries become so extensive that a restorative or endodontic procedure would not be possible, then an extraction may be the only treatment option feasible. Similarly, if periodontal health has deteriorated to such an extent that there is inadequate structure to support the tooth, and reconstruction is not possible, then an extraction may be the only treatment option.

There are many reasons that early intervention does not occur. The IHS provides much dental care to the AI/AN communities; however, there is often more need than available personnel to address the need. Access to early interventional care may be also limited due to distance to care, access to transportation, difficulty in arranging time from work or child/elder care, existing medical conditions, financial concerns, healthcare beliefs, and lack of information as to what is possible once there is severe pain with gross decay, or excessive tooth mobility.

Overall, the dental visits in 2020 in the USA for adults aged ≥18 years were 63.0%27. The result from the present survey for dental visits is much lower, with 54.7% of AI/AN participants indicating a dental visit within the previous year. There is a need to reduce the disparity; however, the Healthy People 2030 data and objectives, which use Medical Expenditure Panel 2016 data, indicate a baseline of 43.3% of US children, adolescents and adults used the oral healthcare system in 2016. The developers of the 2030 objectives from the US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion set a 2030 minimally statistical significant target increase to 45.0%28. This objective will not adequately address oral healthcare needs and oral healthcare disparities. More research is needed in providing equitable access for whole health.

Strengths and limitations

Using existing nationally available data has the strength of a large number of responses and a large number of available variables. However, doing so also has inherent limitations. The previously collected data are limited to what the original researchers’ interests were. The data are cross-sectional and causality cannot be determined in cross-sectional data. The study results are based upon self-report with the potential of bias from poor recall and misclassifications from wanting to please the researcher (social desirability bias). Additional variables (personal infection control measures such as brushing and flossing) could have been useful and would have contributed to the study.

Conclusion

There were significantly more people with missing teeth among rural AI/AN adults as compared with urban AI/AN adults. Interventions addressing rural AI/AN adults in maintaining teeth are critically needed. Future research should involve AI/AN participant-led or included teams to advance oral healthcare in AI/AN communities. Although the IHS is primarily charged with clinical provision of care, IHS–tribe partnerships to facilitate short term goals have the potential to expand research and improve oral health care26. Such partnerships should be expanded in the future.

Acknowledgement

The project described was supported (although not financially) by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, under award 5U54GM104942-04. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Researcher declaration

The sole researcher for this secondary data analysis was non-Indigenous. She has worked as an IHS dentist for the Mohawk and Objibwa tribes and is currently an Associate Professor at West Virginia University in the Department of Dental Public Health and Professional Practice where she is devoted to dental health care for vulnerable populations.