Introduction

Globally, there is an alarming health disparity between urban and rural populations. In the USA, rural residents consistently rank lower on numerous health indicators, experience higher incidences of preventable death related to comorbid conditions, and have reduced life expectancy compared to their urban counterparts1. Internationally, however, disparity in rural health is not universal – some rural populations experience lower preventable mortality rates compared to their urban counterparts2,3. These mixed findings are probably intimately related to differences in regional characteristics of rural populations4. Nonetheless, the United Nations has specifically identified goals for improving rural health5. Although the quality of rural health care is, in part, determined by a complex interplay of various social determinants of health, some of this disparity may be perpetuated by the unique challenges healthcare providers face in rural settings.

Understanding barriers that providers and patients face in delivering and obtaining rural health care, respectively, is important to improving the quality of care. Within the USA, formal assessment of the rural patient perspective has been undertaken, with patients consistently citing transportation and timely access to providers as primary barriers to obtaining care6. Similarly, the perception of providers working in rural areas is being increasingly studied7,8. Survey data from Alaska’s primary care providers characterized some of these challenges9. Providers tended to highly rank patient financial hardship (including lack of health insurance), access to specialty referrals, mental health coverage, travel/transportation, and lack of reimbursement for telehealth as notable barriers to providing care9. Another state-based survey of physicians in Nebraska revealed that affordability of care and general availability of providers were common problems for rural health care10. More recently, a qualitative analysis within Montana examined the relationship between the patient and provider as it relates to communication, citing lack of cultural awareness as a potential barrier to an effective patient–provider relationship8. While these data provide a foundation from which to understand existing challenges to caring for rural populations, rural residents continue to experience barriers to accessing health care11. Part of the difficulty in bridging this gap probably stems from the diversity of rural populations – the barriers experienced in one region may not be relevant in another region in which the underlying socioeconomics, infrastructure, culture, and penetration of health care are different12. Therefore, continued understanding of regional barriers is necessary to provide policy-makers with a more complete picture of the challenges facing rural health care so they may better direct efforts towards improving quality for these populations.

For these reasons, a qualitative study was conducted to understand the perceptions of primary care physicians in Pennsylvania about barriers to providing health care for patients living in rural areas. Qualitative assessment allows for a deeper understanding of barriers as well as what providers may find most useful in overcoming these barriers. Furthermore, Pennsylvania offers a unique setting to examine the barriers to rural health care given that almost 27% of the state’s population resides in rural areas, making it the third largest rural population in the USA13.

Methods

Study design

A systematic thematic content analysis was conducted to identify topics relevant to rural healthcare barriers14. The objective was to identify barriers to providing health care in rural Pennsylvania as experienced by primary care providers in order to define actionable items that future policy-makers may use to improve care for rural populations. Semistructured interviews were conducted with primary care physicians practicing in rural counties in the state of Pennsylvania.

Interview guide

The construction of the interview instrument was approached by using a team-based iterative approach. This began with discussions among a multidisciplinary research team to define key topics relevant to rural healthcare barriers. The thematic domains included (1) overall barriers to rural health care, (2) financial barriers, (3) availability of providers, both primary and specialists, (4) infrastructure to facilitate care coordination, (5) travel distance and transportation, and (6) healthcare literacy.

Participants

Participants were initially selected for interviews by using a purposeful sampling technique15. Potential participants were identified by emailing practices in rural counties with designations of rural health centers or federally qualified health centers13. Providers within these practices were asked if they would be willing to participate in the study. Additional participants were identified by asking previous participants to recommend another individual to participate, a technique known as snowball sampling16. Interviews were conducted until thematic saturation was achieved, which was defined as three consecutive interviews in which no new information was generated17,18. Based on established literature, it was anticipated that thematic saturation would be reached by 15–20 interviews18.

Interviews

All interviews were conducted by a single researcher (AM). Participants were contacted on the telephone number they provided within the initial email communication and a description of the project was given. Participation was completely voluntary and verbal informed consent was obtained according to a predetermined script. Interviews were audio recorded and lasted approximately 30 minutes.

Data analysis

All interviews were transcribed verbatim with identifying details removed. Samples of transcripts were reviewed by interviewers to ensure accuracy. Two qualitative specialists (MH and RW) developed a codebook using an iterative process to identify data that represented a unique concept. Cohen’s kappa statistics were used to assess intercoder reliability in application of codes, with an average kappa score of 0.6819, indicating substantial agreement. The coders met to adjudicate all coding discrepancies. Codes were then further investigated by the study team examining for patterns within each code and examining for relationships between codes to develop themes14. The primary coder produced a report reflecting the themes they found in the interviews, and this report was discussed with the rest of the team as a form of investigator triangulation.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board (PRO 18100192). Participants all provided informed consent for audio-recording. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

All participants were current providers in rural counties in the state of Pennsylvania and included 18 men and 2 women. This demographic distribution was consistent with the underrepresentation of women in the rural healthcare workforce, and therefore additional sampling was not performed20. While all physicians had community-based practices, 55% (n=11) had some affiliation with a larger health system. Participants had a range of 2–25 years of practice experience in rural settings.

Participants uniformly expressed that providing care in a rural setting was challenging due to a unique set of problems that were unlike those faced by their urban counterparts. During the interviews, participants generally described and characterized the rural communities in which they worked. Although each community varied somewhat, particularly with respect to the local cultural and ethnic groups, there were many commonalities that distinguished rural from urban communities. These differences were emblematic of a unique set of attitudes and beliefs characteristic of what participants referred to as a ‘rural culture’. Understanding this culture helped providers establish a relationship with their patients. This relationship was imperative to helping patients understand their health conditions and the recommended treatments. For instance, participant 12 described their patients as hesitant to seek medical care:

I think there’s a little bit more skepticism of the medical community and educated people among some of the rural, more rural population they tend to be a little more untrusting of medicine. (Participant 12)

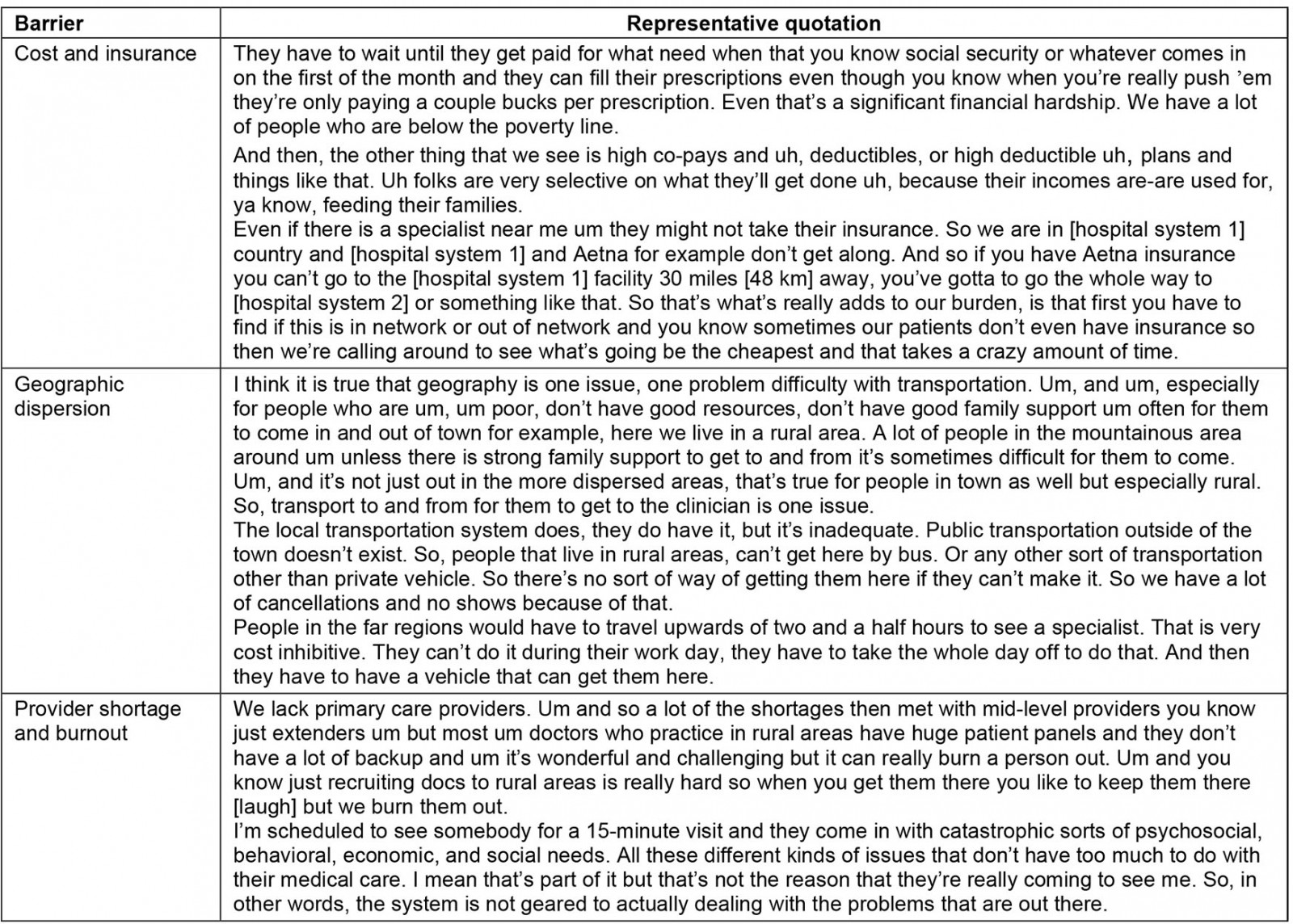

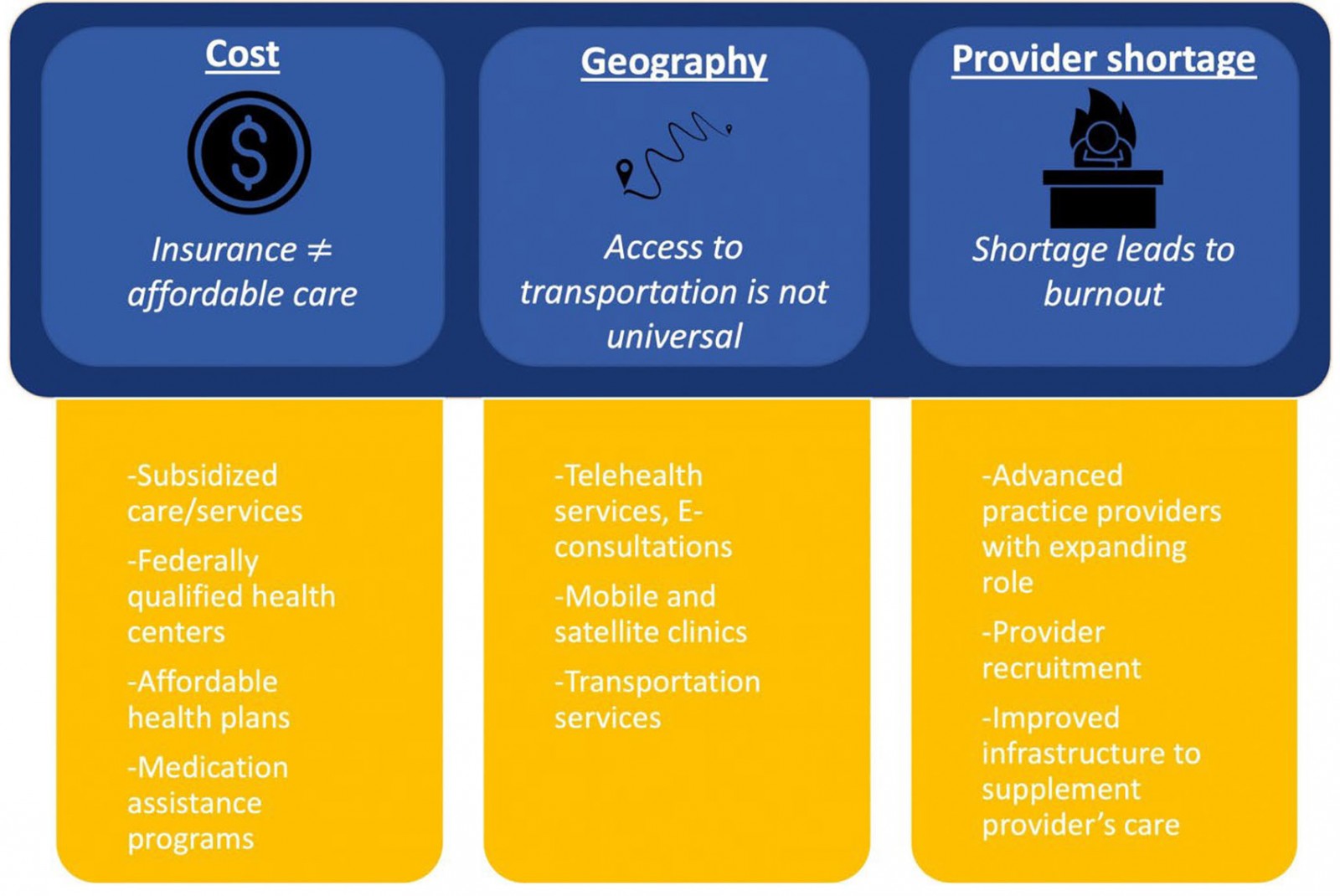

In this instance, as participant 12 noted, patients’ mistrust of medical care required caregivers to provide more detailed explanations about treatments and why they may or may not be necessary. Therefore, providing care to rural populations required an understanding of the unique local culture. Aside from a socially unique patient population, participants discussed the specific barriers they faced in providing patients with quality care (Table 1, Fig1).

Table 1: Barriers to rural health care and representative quotations from participants

Figure 1: Key barriers to rural health care as identified by participants, and proposed solutions.

Figure 1: Key barriers to rural health care as identified by participants, and proposed solutions.

Barriers to rural health care

1. Cost and insurance: Nineteen of 20 participants believed that financial barriers made it difficult for them to provide adequate care for their patients. Many participants cared for an impoverished patient population. As a result, costs prohibited their patients from obtaining medications, completing diagnostic testing, and complying with treatment. One participant described the challenges their patients faced.

They have to wait until they get paid for what [they] need when that you know social security or whatever comes in on the first of the month and they can fill their prescriptions even though you know when you really push them, they’re only paying a couple bucks per prescription. Even that’s a significant financial hardship. We have a lot of people who are below the poverty line. (Participant 5)

Participants described many patients as having to live paycheck to paycheck, which delayed obtaining necessary medication. Many patients had to forgo their prescriptions altogether and prioritize their money for other living essentials such as food and transportation. Participant 3 specifically discussed patients being unable to pay US$500 (A$750) for a supply of insulin, an essential medication for diabetics. Furthermore, having insurance did not equate to being able to afford health care. Participants reported that patients often found co-pays or deductibles of their insurance plans unaffordable.

And then, the other thing that we see is high co-pays and uh, deductibles, or high deductible uh, plans and things like that. Uh, folks are very selective on what they’ll get done uh, because their incomes are used for, ya know, feeding their families. (Participant 17)

Most participants characterized their patients as insured, either through Medicare, Medicaid, or other supplemental assistance programs. However, nine participants felt that insurance did not provide adequate coverage for clinic visits, medications, and other necessary treatments. Furthermore, insurance limited patients’ access to care.

I do a lot of addiction work and so, sometimes they’ll drop out because they can’t afford to get their urine drug screening done, things like that. So, they fall out of treatment and everything. (Participant 17)

Lack of adequate coverage directly resulted in patients dropping out of potentially lifesaving addiction programs. This insurance limitation was also true for specialty care. Specifically, local specialty providers tended to reject Medicaid and other federal assistance programs, making it hard for patients to obtain the advanced care they required.

For the specialty care, there are some specialists like dermatology, endocrinology, rheumatology where they don’t want to take medical assistance. So for them, we can’t refer even to regional specialists, we actually have to send them a couple hours out of the area to the tertiary or quaternary area centers. (Participant 20)

Participants struggled to get their patients to the appropriate specialists and often did not have the staff or infrastructure to assist patients in following through with their referrals.

Financial hardships were not exclusive to patients. Participants struggled to provide adequate care due to their own financial constraints. For instance, participants cited difficulty in affording additional staff and providing an infrastructure for ancillary services (eg social work, care coordination). Participants described a delicate balance between having enough providers to prevent burnout and having too many providers to stay financially afloat.

What we found is if you over or understaff by half a provider in a community it might be the difference between you being able to keep your doors open or not. Or getting overwhelmed and burnt out. (Participant 8)

While participants needed more staff, they often could not afford to hire them. Some participants were able to overcome these challenges through partnership with larger health systems located in nearby urban areas. These partnerships tended to allow for establishment of an electronic health record and support staff. However, a few participants discussed the negative impacts of having large health networks in the area.

In our market, [hospital system 1] and [hospital system 2] are driving up primary care rates where the larger [hospital system 2] is offering 260 000 or more for family practice physician and it’s not a sustainable environment … as a small system you have to be competitive with that but then how do you pay the freight there. (Participant 4)

Participants’ small office practices could not compete with the wages offered by larger health systems. Rising costs driven by large health system expansion made it increasingly unsustainable for existing rural providers to remain competitive in these markets. Additionally, participant 15 described how partnership with larger networks pushed services that were once performed locally at affordable rates out of the community to tertiary care centers that charged much higher rates.

It is being driven especially from bigger corporate hospitals because they get better reimbursement when a specialist does the procedures than when a family care doctor does the procedure, insurance reimbursement rates are different. (Participant 15)

2. Geographic dispersion: All participants described patients in rural areas as having to travel long distances to reach their providers, sometimes totaling over 4 hours round trip.

I think it is true that geography is one issue, one problem difficulty with transportation … especially for people who are um, um poor, don’t have good resources, don’t have good family support, um often for them to come in and out of town for example, here we live in a rural area. A lot of people in the mountainous area around um unless there is strong family support to get to and from it’s sometimes difficult for them to come. Um, and it’s not just out in the more dispersed areas, that’s true for people in town as well but especially rural. So, transport to and from for them to get to the clinician is one issue. (Participant 2)

The barrier of distance was exacerbated by the lack of public transit and poverty. Participants described patients as being unable to afford a car or pay for gas. As a result, many relied on friends or family for transport. Those who could not get transport missed their visits or sometimes walked (up to 9 miles (14.5 km) as one participant noted) to see their provider.

They would have to travel upwards of two and a half hours to see a specialist. That is very cost prohibitive. They can’t do it during their work day, they have to take the whole day off to do that. And then they have to have a vehicle that can get them there. (Participant 17)

Because of the long travel distance, patients would have to forfeit a day of income to get to their appointment, which for many was not a trivial sacrifice to make.

3. Provider shortage: The geographic dispersion of providers was further compounded by shortage of providers, both in primary and specialty care. Many participants discussed their motivation for practicing in rural areas, which included proximity to family, preference for rural communities, and a passion for rural medicine. However, participants expressed difficulty in attracting new providers to the area.

We lack primary care providers. Um and so a lot of the shortages then met with mid-level providers you know just extenders um but most um doctors who practice in rural areas have huge patient panels, and they don’t have a lot of backup and um it’s wonderful and challenging but it can really burn a person out. Um and you know just recruiting docs to rural areas is really hard so when you get them there you like to keep them there [laugh] but we burn them out. (Participant 11)

Eleven other participants described the lack of primary providers and the downstream consequences, including higher patient volumes, which resulted in burnout among the existing providers. Most new providers would only commit to 1- or 2-year contracts and leave the community after their contract ended because of the mounting workload.

Not only did patient volumes lead to burnout and loss of providers, but four participants specifically mentioned being unable to provide patients with adequate care.

I’m scheduled to see somebody for a 15-minute visit and they come in with catastrophic sorts of psychosocial, behavioral, economic, and social needs. All these different kinds of issues that don’t have too much to do with their medical care. I mean that’s part of it but that’s not the reason that they’re really coming to see me. So in other words, the system is not geared to actually dealing with the problems that are out there. (Participant 10)

As participant 10 described, providers had to prioritize medical complaints and often disregard psychosocial complaints – which were felt to be equally important – due to time constraints.

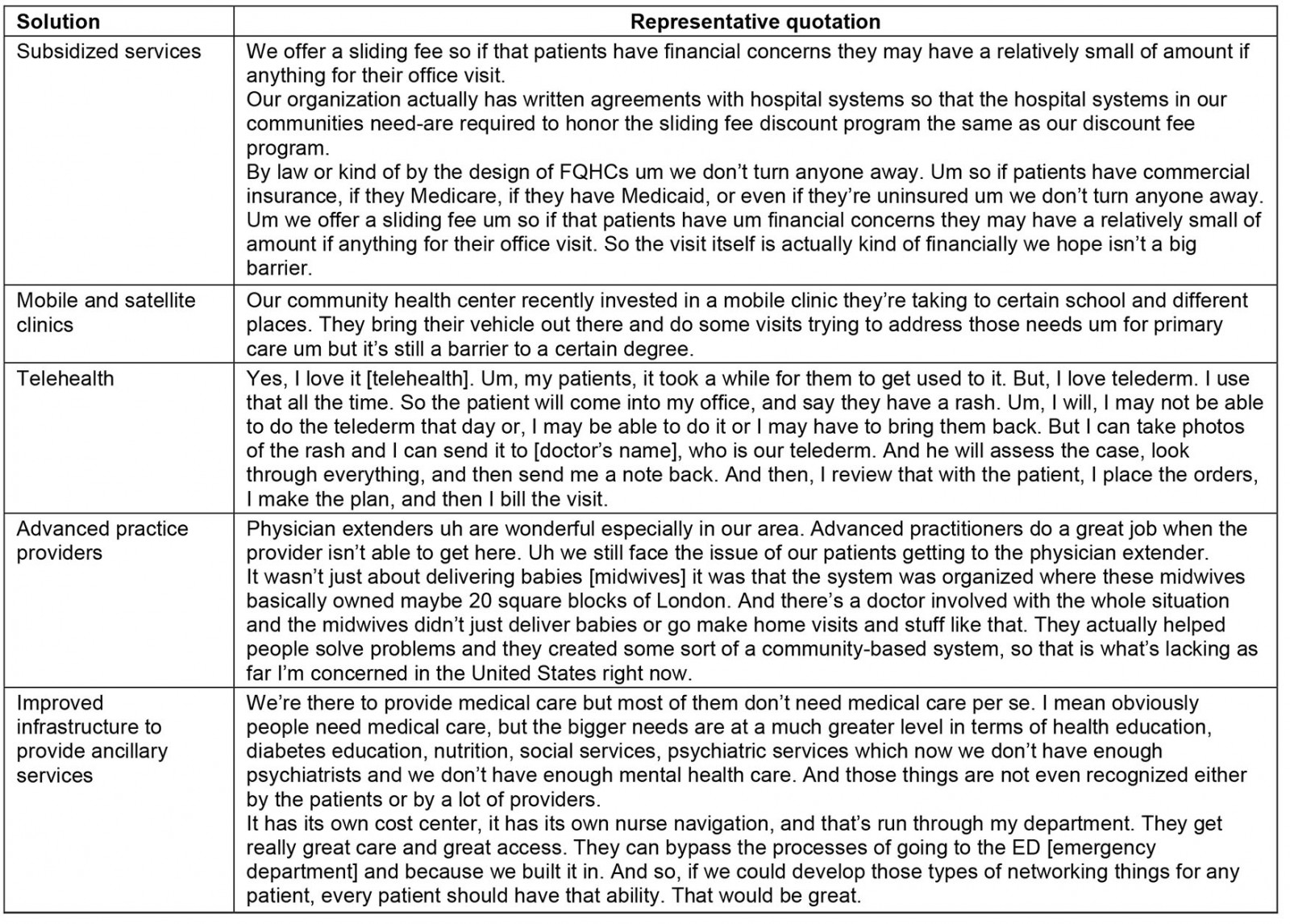

Strategies to overcome barriers

Providers described potential strategies that could help their clinics overcome barriers so they may meet the healthcare needs of their patients (Table 2).

Table 2: Potential solutions participants discussed to address barriers

1. Subsidized services: Several participants discussed subsidized services to alleviate some of the cost-specific barriers. A number of clinics and hospitals established an infrastructure to provide free transportation up to 100 miles (160 km) for patients.

Um our hospital also provides free cab vouches for high-risk people. Um and you know it can transport somebody up to 75 or 100 miles [120 or 160 km]. Um and our hospital pay it if they really need to. Um but it is a big deal, it’s a big deal. (Participant 8)

However, paying for this transportation was difficult for clinics and smaller hospitals.

Other participants discussed federal programs that designated hospitals and clinics as federally qualified health centers, allowing for subsidized office visits and sometimes discounted hospital stays.

By law or kind of by the design of FQHCs [federally qualified health centers] um we don’t turn anyone away. Um so if patients have commercial insurance, if they Medicare, if they have Medicaid, or even if they’re uninsured um we don’t turn anyone away. Um we offer a sliding fee um so if that patients have um financial concerns they may have a relatively small of amount if anything for their office visit. So the visit itself is actually kind of financially we hope isn’t a big barrier. (Participant 7)

Cost barriers for office visits may be mitigated through federal funding; however, the cost of procedures, hospital visits, and medications continued to be a challenge for patients. One participant discussed helping patients apply for patient assistance programs through drug companies to obtain high-cost prescriptions.

You get you know seniors who have Medicare products of some sort so that uh prescription coverage and they get into the donut hole and you know they just can’t afford the medication so they just stopped taking it. For various people we try and encourage them to use patient assistance programs through the drug companies. So that actually is very time intensive though if we drill it down that’s really the issue then we can actually help them with that but a lot of patients won’t disclose that to you they’re too embarrassed of their actual financial barriers and can’t pick up their medicines. (Participant 5)

As participant 5 noted, such assistance programs are severely limited owing to the time commitment to apply and the difficulty in recognizing which patients may qualify for them. Participant 11 discussed how their patients exclusively relied on medications from the clinics ‘sample closet’, which consisted of medications drug representatives provided.

2. Mobile and satellite clinics: Participants discussed mechanisms to circumvent transportation issues by bringing health care directly to the patients. For instance, some discussed investment in mobile health clinics to overcome transportation barriers.

Our community health center recently invested in a mobile clinic they’re taking to certain schools and different places. They bring their vehicle out there and do some visits trying to address those needs for primary care. (Participant 9)

Mobile clinics allowed provision of basic primary care services and screening to local communities at convenient locations. Other participants described the use of satellite clinics to deliver additional specialty care to communities in need – up to 40 miles (64 km) away from their primary clinic site. However, staffing the clinics proved to be challenging and often was only feasible once a month.

Some participants traveled directly to patients by making house calls. One participant discussed use of this strategy with their Amish patient population.

I care for a lot of the Amish and so like half my practice is Amish which I do home visits out to their area. We go out about 50 miles [80 km]. (Participant 8)

In addition to physicians, other members of the care team, including nurses and advanced practice providers, also made home visits when possible. However, the long travel times made such systems difficult to sustain.

3. Telehealth: Telehealth was discussed by almost all participants as a potential mechanism to overcome local provider shortage and geographic dispersion. Nine participants specifically described the use of telehealth in their practice. Telehealth was primarily used to obtain specialty care. Dermatology, endocrinology, psychiatry, and infectious disease were among the most common specialties mentioned.

Yes, I love it [telehealth]. Um, my patients, it took a while for them to get used to it. But, I love telederm. I use that all the time. So the patient will come into my office, and say they have a rash. Um, I will, I may not be able to do the telederm that day or, I may be able to do it or I may have to bring them back. But I can take photos of the rash and I can send it to [doctor’s name], who is our telederm. And he will assess the case, look through everything, and then send me a note back. And then, I review that with the patient, I place the orders, I make the plan, and then I bill the visit. (Participant 13)

Telehealth was employed in varying ways by participants. Some participants requested e-consultations from specialists. Other participants had patients come to their clinic where they would have the telecommunication infrastructure in place to connect with the specialists, given many patients did not have either the electronic capabilities or internet access.

Eight participants had not yet incorporated telehealth in their practice but felt that it could alleviate several issues, particularly obtaining specialty care for their community. However, all these same participants described shortcomings of telehealth.

Well um yes now there are certain specialties that are ideal for telehealth and then there are others that are just not that helpful. And I’ve done a lot of look into this. Um you know one of my friends is … a telecare doctor … you know, in some ways it works … if you have a relationship with a doctor and they’re not necessarily always available you know to actually do more of a telehealth, once that relationship is established it works out great. (Participant 8)

Much of the criticism of telehealth revolved around the inability to physically examine the patient. Most participants noted that telehealth could be useful for some specialty care and follow-up, but less so for primary care. Participants were concerned about the unique aspects of rural residence that made telehealth challenging, such as lack of internet access and appropriate electronic devices.

4. Advanced practice providers: The physician shortage made it challenging for providers to handle the existing case load and for patients to obtain timely care. Several participants believed advanced practice providers could improve access to care.

Physician extenders uh are wonderful especially in our area. Advanced practitioners do a great job when the provider isn’t able to get here. Uh we still face the issue of our patients getting to the physician extender. (Participant 6)

Advanced practice providers may address the provider shortage; however, recruiting them to rural areas and getting patients to the clinics still posed challenges. Regardless, the expanding role of advanced practice providers may allow them to have unique impacts within rural communities. They may not only help improve timely access to care, but they may also improve community engagement. One participant likened the potential impact of advanced practice providers on rural communities to that of midwives in historic London.

It wasn’t just about delivering babies [midwives] it was that the system was organized where these midwives basically owned maybe 20 square blocks of London. And there’s a doctor involved with the whole situation and the midwives didn’t just deliver babies or go make home visits and stuff like that. They actually helped people solve problems and they created some sort of a community-based system, so that is what’s lacking as far I’m concerned in the United States right now. (Participant 10)

5. Improvement in infrastructure: Participants discussed investment in infrastructure for ancillary services that would specifically address the needs of rural communities. Participants lacked the ability to provide adequate medical education, mental health services, and social support for patients.

We’re there to provide medical care but most of them don’t need medical care per se. I mean obviously people need medical care, but the bigger needs are at a much greater level in terms of health education, diabetes education, nutrition, social services, psychiatric services which now we don’t have enough psychiatrists and we don’t have enough mental health care. And those things are not even recognized either by the patients or by a lot of providers. (Participant 10)

While medical services are important, rural populations had specific needs that were going unmet due to lack of support services.

Participants felt that better infrastructure would allow for improved care coordination. Specifically, having nurse navigators to help patients obtain medications, follow through with diagnostic testing, and coordinate referrals to specialists could remedy some of the problems they faced. One participant described their clinic’s infrastructure for their specific rural community.

It has its own cost center, it has its own nurse navigation, and that’s run through my department. They get really great care and great access. They can bypass the processes of going to the ED [emergency department] and because we built it in. And so, if we could develop those types of networking things for any patient, every patient should have that ability. That would be great. (Participant 17)

Because of their inability to get to their primary providers in a timely manner, patients would overuse the emergency department for primary care services. In this instance, the participant described a unique infrastructure for their community that allowed for minimization of emergency department use. However, such infrastructure requires monetary capital, and the services rendered by it are not directly reimbursed, making it challenging to maintain.

Discussion

Access to and quality of health care remains one of the biggest challenges facing rural communities in the USA and internationally. Rural residents continue to rank poorly on numerous health indicators compared to their urban counterparts, suggesting health systems are failing this vulnerable population. The authors attempted to better understand the barriers to rural health care in one of the largest rural populations in the USA by interviewing primary care providers and using qualitative methods. The primary barriers that emerged were cost and insurance, geographic dispersion and provider shortage and burnout. Many participants also discussed potential solutions, including subsidizing essential services and office visits, establishing mobile or satellite health clinics, increasing utilization of telehealth, expanding the role of advanced practice providers, and improving care-delivery infrastructure to include ancillary services that are tailored to the needs of the community.

Lack of financial resources affected how providers were able to deliver care. Specifically, they were unable to improve clinic infrastructure to provide ancillary services that could help meet the psychosocial needs of their patients. Currently, rural hospitals and clinics within the USA and internationally are financially precarious, resulting in an increased rate of closures21,22. Closures may be due to hospital inefficiencies as well as the declining market they serve. For instance, rural hospitals tend to cater to a smaller patient population, perform fewer high-reimbursement services, and obtain fewer reimbursements from private payers. This makes it difficult for them to recover their operational costs21. These problems are further exacerbated by increasing expansion of larger health systems, driving up prices in local markets, making it difficult for existing rural providers to remain competitive23. In order to help prevent further collapse of rural health care, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services initiated the Rural Health Model, to be piloted in Pennsylvania24. Under this model, participating rural hospitals will receive all-payer global budgets, a fixed amount of money that is set in advance based on historic revenue and funded by all participating payers, to cover the inpatient and outpatient services they provide. Rural hospitals will use this predictable funding to redesign the care they deliver to improve quality and meet the health needs of their local communities. The goal is not to simply expand services, but to focus on providing needed services that are community specific.

Just as providers and hospitals experience financial hardship, patients often face difficulty managing co-pays and paying for prescription medication. One participant noted that patients dropped out of opioid addiction programs because they were unable to afford the required urine drug screens. It was surprising to note that these financial hardships were encountered despite many of the patients being insured. Rural workers tend to be self-employed, and therefore often seek out their own insurance rather than obtaining employer insurance25. Under the previous administration, the 2010 Affordable Care Act’s cost-sharing reduction for plans was cut, leading to fewer market plans and increased premiums for some of the remaining plans26. There is concern that this may lead to more out-of-pocket costs, higher deductibles, and increased premiums for some consumers. In fact, after the subsidy payment cuts were implemented, rural residents barely above the 400% federal poverty level were paying the highest premiums per month of all consumers, which amounted to several hundred dollars more than what they were paying previously26. In light of this, many states, such as Minnesota and California, are offering their own subsidization of insurance plans to aid this patient population26. Internationally, similar initiatives have been enacted to reduce financial burden for rural populations, such as omission of co-pays or subsidies (up to 80%) of insurance premiums27,28.

Geographic dispersal further compounds this problem, with healthcare infrastructure being more spread out in rural areas29,30. For instance, metropolitan areas in the USA have 11.5 oncologists while rural areas have 0.5 oncologists per 1000 square miles (2600 km2)29. The barrier of geographic dispersion is made even more challenging to overcome as patients may be unable to afford transportation costs or forgo a day of work to make their appointments. While some may rely on public transportation, it is not a viable solution because it is either unavailable or limited in scope. Transportation becomes a particularly critical issue for those requiring specialty care. For example, surgical cancer care is not ubiquitous. One in five rural Americans were found to live more than 60 miles (97 km) from a medical oncologist and one in 10 had to travel over 2 hours to reach a cancer surgeon31. The travel burden is not just an inconvenience, it also poses significant financial hardship and can negatively impact health outcomes (eg delayed diagnosis, delayed treatment, and inability to complete treatment)29,32,33. Many countries, including Canada and Australia, experience challenges with geographic dispersal. Programs in these countries include establishment of formal collaborative networks between local providers and outside specialists, allowing specialists to travel to more remote regions, and improving broadband capacity to rural areas to enable tele-visits34.

The lack of transportation infrastructure can lead rural residents to rely on ambulances and emergency rooms for routine care. In non-emergency situations, patients often cite the lack of affordable transportation as a major barrier to care access35. In order to fill the gap, payers and policy-makers should consider efforts to utilize existing community transit resources for medical transportation or reimburse patients who use ride-sharing services in areas that lack public transit or taxi services. Another option would be to formalize volunteer services for medical transit. For instance, Oregon offers a tax credit for volunteer rural emergency medical services providers, who provide medical and transportation services36. Missouri has proposed a model in which providers partner and assume the costs of transportation, and in doing so, they recoup the lost revenue from missed appointments37. Over a 17-month period, the Ozark Medical Center received US$7.68 (A$11.50) in reimbursement for every A$1 invested in transportation37,38. Internationally, similar mechanisms of decentralizing infrastructure development and transportation have been proposed and enacted by engaging community-based contractors to work alongside governmental departments39.

The barrier of geographic dispersion is further compounded by difficulties in recruiting providers to rural communities, particularly those providing specialty care. While 20% of Americans reside in rural areas, only 9% of physicians practice in these areas, implying that the overall workforce is small40. The existing workforce will also diminish as nearly 30% of rural primary providers are entering retirement age41. This provider supply will continue to decline because the number of medical students from rural communities, who are the most likely to practice in rural areas, has fallen to less than 0.5% over the last 15 years42. Importantly, lack of providers make it difficult for patients to receive care, but it also imparts additional burden on the existing providers as a consequence of high patient volume, which may lead to burn out43. Globally, universities are attempting to combat this problem by utilizing educational and financial incentives, providing specific longitudinal training in rural practices and issuing incentives to retain the newly trained workforce, respectively30.

The current findings should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, the opinions are based on interviews with 20 primary providers in rural areas in the state of Pennsylvania, which may limit its generalizability. However, the scope was limited to Pennsylvania with the knowledge that it has one of the largest rural populations in the country, and physicians were purposefully selected with varying practice structure and experience. Additionally, barriers will differ across states due to varying health-related policies, and therefore the authors chose to limit the scope of this study to one state to ensure a consistent policy context. Second, the majority of participants who were interviewed were male; however, the study was not designed to select participants based on gender. Third, qualitative studies are subjective by design. However, interviews were performed until thematic saturation was reached and rigorous qualitative methodology was used by two experienced coders with assessment of intercoder reliability.

Conclusion

As the rural–urban healthcare gap continues to grow, it is crucial to develop methods for rectifying this disparity. Based on what providers have perceived, there are several potential areas to target policy initiatives. Rural patients experience financial burden, which limits their ability to access or engage with health care. Reducing the number who are insured may mitigate financial stress, particularly in the USA in which states with large rural populations have yet to expand Medicaid coverage. Furthermore, increasing funding for rural clinics can help subsidize patient costs and provide needed ancillary services, such as care coordination. Geographic dispersal of health services, lack of specialty providers, and lack of transportation continue to be a challenge. More flexible payment models (ie global payments) may help preserve existing hospitals and clinics in rural areas. Expansion and reimbursement of telehealth services may improve access to specialty care, but only if broadband services are also expanded. Some care inevitably requires face-to-face interactions, which can be facilitated by increasing the role of advanced practice providers in these areas and providing stronger incentives beyond loan forgiveness to attract and retain physicians. Additionally, some care may also be delivered by other ancillary providers, including emergency medical service, pharmacists, and community health workers, all of whom can directly engage with community members to improve healthcare literacy and provide basic screening services. While many initiatives have been initiated globally, further research is needed to understand effective solutions and the contexts in which they are employed.

Funding statement

Bruce Jacobs is supported in part by P30CA047904 from the National Cancer Institute and the Henry L. Hillman Foundation. Avinash Maganty is supported in part by the Thomas H. Nimick, Jr Competitive Research Fund.