Introduction

All six Australian states have now passed voluntary assisted dying (VAD) laws. At the time of writing, VAD laws have commenced in three states (Victoria, Western Australia (WA) and Tasmania), with the other state laws coming into effect before the end of 2023, following a designated implementation period. Despite jurisdictional variation, each regime enables terminally ill adults to access VAD provided they satisfy legislative eligibility criteria as assessed by two qualified medical practitioners. If a person is deemed eligible, the VAD substance will be dispensed by the Statewide Pharmacy Service and will either be administered by the person (self-administration) or by an eligible practitioner (practitioner administration).

As is the case with many health services, inequitable access to VAD within regional communities is a pressing concern and has been described internationally1. Empirical evidence from Victoria (the first Australian jurisdiction to implement VAD laws) has revealed that regional patients have experienced access difficulties, mainly attributable to the lack of local providers2.This has necessitated terminally ill patients to travel to metropolitan Victoria to access VAD2,3.

Access has also been hampered in Victoria due to the prohibition of the use of telehealth in the VAD context3-10. Guidance issued by the Victorian Government stipulates that all ‘discussions, consultations and assessments with patients, family and carers regarding [VAD] must occur face-to-face’ (p. 15)11.This guidance reflects concerns that the use of telehealth in the VAD context may breach the Commonwealth Criminal Code Act 1995, an Australian federal law that makes it an offence to use a ‘carriage service’ (eg phone, fax, videoconference, email) to discuss ‘suicide’. Victoria’s guidance adopts a conservative approach that is arguably unnecessarily restrictive given commentators have suggested that aspects of the VAD process can occur via telehealth without contravening the federal law4,5. Providing general information about the availability of VAD, providing contact details of a VAD provider and conducting eligibility assessments are unlikely to breach the law, but any discussion and processes relating to the prescription or dispensing of the VAD substance might be a breach4,5. A more nuanced position has been adopted in WA’s Voluntary Assisted Dying Act 2021, where telehealth is permitted to some extent, subject to the Commonwealth Criminal Code12.

As the second Australian jurisdiction to pass VAD laws, WA drew on the Victorian experience and committed to ensuring equitable access13. Such a commitment stemmed from concerns that the geographically vast nature of WA would likely compound access inequities for regional residents (ie persons who reside outside the metropolitan region)13. Accordingly, several initiatives were introduced during the law-making and implementation stages of the WA legislation to facilitate access14. Such initiatives included:

- introducing legislative guiding principles promoting equity of access

- broadening (in comparison to Victoria) the qualification requirements for participating medical practitioners

- permitting nurse practitioner administration

- mandating data collection in relation to regional access to facilitate monitoring

- issuing an access standard (which details how WA will facilitate regional access)

- introducing obligations on conscientious objectors

- ensuring statewide VAD services (Statewide Care Navigator and Statewide Pharmacy Service) are accessible to all WA communities

- permitting the use of telehealth (insofar as is permitted by the Commonwealth Criminal Code)

- establishing a Regional Access Support Scheme (RASS), which provides financial and travel support for patients, a patient’s escort, practitioners and/or interpreters to support regional patients14.

In addition to state-based work led by the WA Government (described above), there is also evidence of local efforts. The WA Country Health Service (WACHS), which is the state’s only public regional health service provider (with services spanning over 2.5 million km2)15, is committed to supporting VAD provision within its catchment16. In addition to supporting patients and employees within its health services, it also works with the other state VAD services (Statewide Care Navigators and Statewide Pharmacy Service) to support safe regional travel and VAD provision across regional WA more broadly17. WACHS, with the coordination assistance of a designated VAD regional lead, provides VAD service personnel with local information and resources (eg fleet vehicles, charter flights and accommodation) to support their regional travel17.

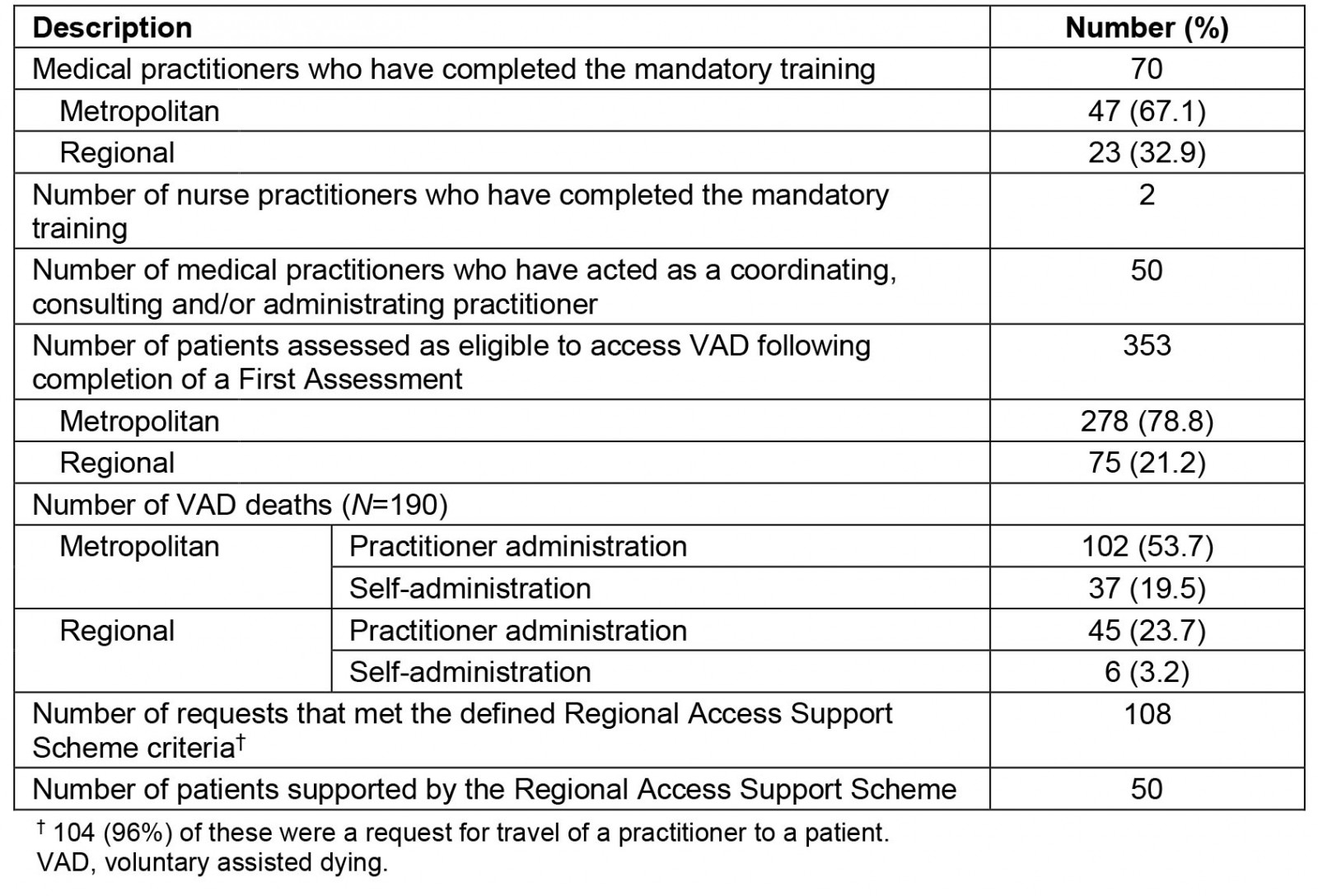

Given VAD in WA has only been a lawful end-of-life choice for a short time, there is limited insight into regional VAD provision. However, the VAD Board’s first annual report gives some indication of how provision is tracking (Table 1)18. The report reveals that the demand for VAD in WA has been much higher than expected, and that the proportions of regional and metropolitan patients seeking and accessing VAD largely mirror the proportions in the WA population19. First requests were made by persons residing in each region of WA, and participating practitioners had a practice address in all regions except the Wheatbelt, the region within regional WA with the third-highest number of VAD first requests18. The RASS was utilised, and indeed facilitated regional access to some extent, being relied on in all but one region (Mid West)18.The Statewide Pharmacy Service travelled to every WA region and met VAD substance supply targets (five business days), except on one occasion due to a flight cancellation18.

Given the limited insight into regional provision to date, this article augments the VAD Board report findings and reports on the early experiences of regional provision in WA based on the reflections of key stakeholders.

Table 1: Key statistics for voluntary assisted dying in Western Australia in the first year of operation (figures correct to 13 June 2022)18,20

Methods

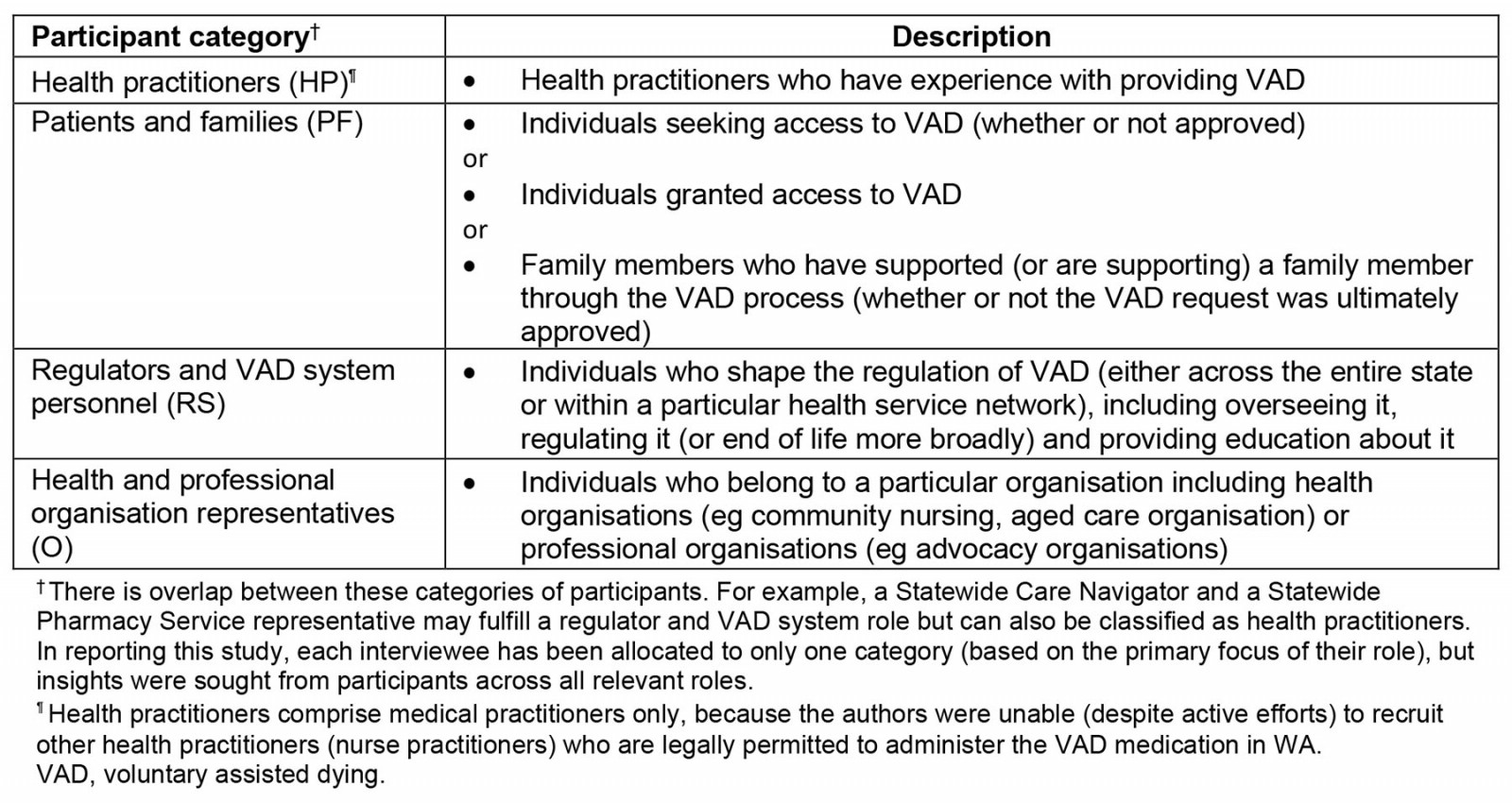

This study utilised purposive sampling with different groups of stakeholders: health practitioners (HP), patients and families (PF), regulators and VAD system personnel (RS), and health and professional organisation representatives (Table 2). A variety of recruitment strategies were adopted including advertising via social media and advocacy organisations, and utilising professional networks and publicly available contact details of individuals known to be involved in the VAD process to contact prospective participants. Snowball sampling was also used.

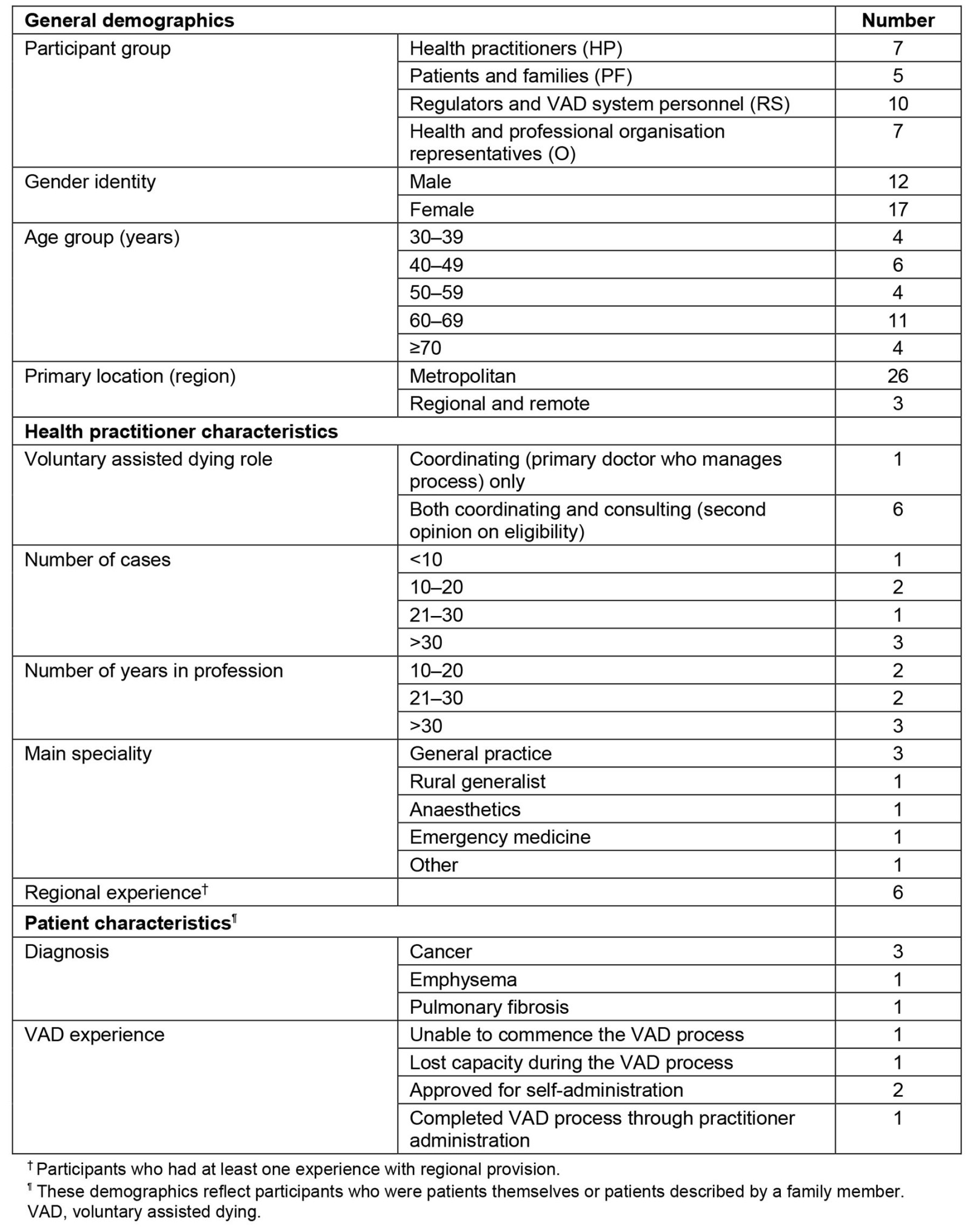

Semi-structured interviews were conducted by CMH (present during all interviews), LW and BPW between March and September 2022 via the videoconferencing platform Zoom or by telephone (see Table 3 for demographics). Separate interview guides were used to accommodate the different types of stakeholders. Each guide contained questions that invited participants to reflect on how the WA VAD regime was operating in practice, and the ability of the WA Act to meet its policy goals and VAD regulation more broadly. Field notes were written following each interview. The interviews were audio-recorded and then transcribed by a professional transcription company. Transcripts were de-identified by CMH, and each participant was sent a copy of their de-identified transcript and invited to review and amend their transcript to ensure comprehensiveness of the data collected.

Transcripts were imported into NVivo v1.6.1 (QSR International: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home). To analyse the data, the authors used inductive thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clarke (2006)21. CMH initially familiarised themselves with the data by listening to the audio recording of each interview and reading through each transcript. CMH then developed a preliminary coding framework. The coding framework was reviewed and revised by LW and BPW, drawing on their previous experience and recollection of the data. The data was then coded according to the revised framework. CMH grouped relevant codes into preliminary themes, and then reviewed and extracted the data relevant to the regional context. CMH then defined and named the themes (and subthemes) arising from the extracted data. These were then verified and endorsed by both LW and BPW and are reported here.

Table 2: Participant categories for stakeholder interviews related to voluntary assisted dying regime in Western Australia

Table 3: Participant demographics for stakeholders in the voluntary assisted dying regime in Western Australia

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was granted Queensland University of Technology Human Research Ethics Committee (Ref 20000002700). Informed consent was obtained before each interview.

Results

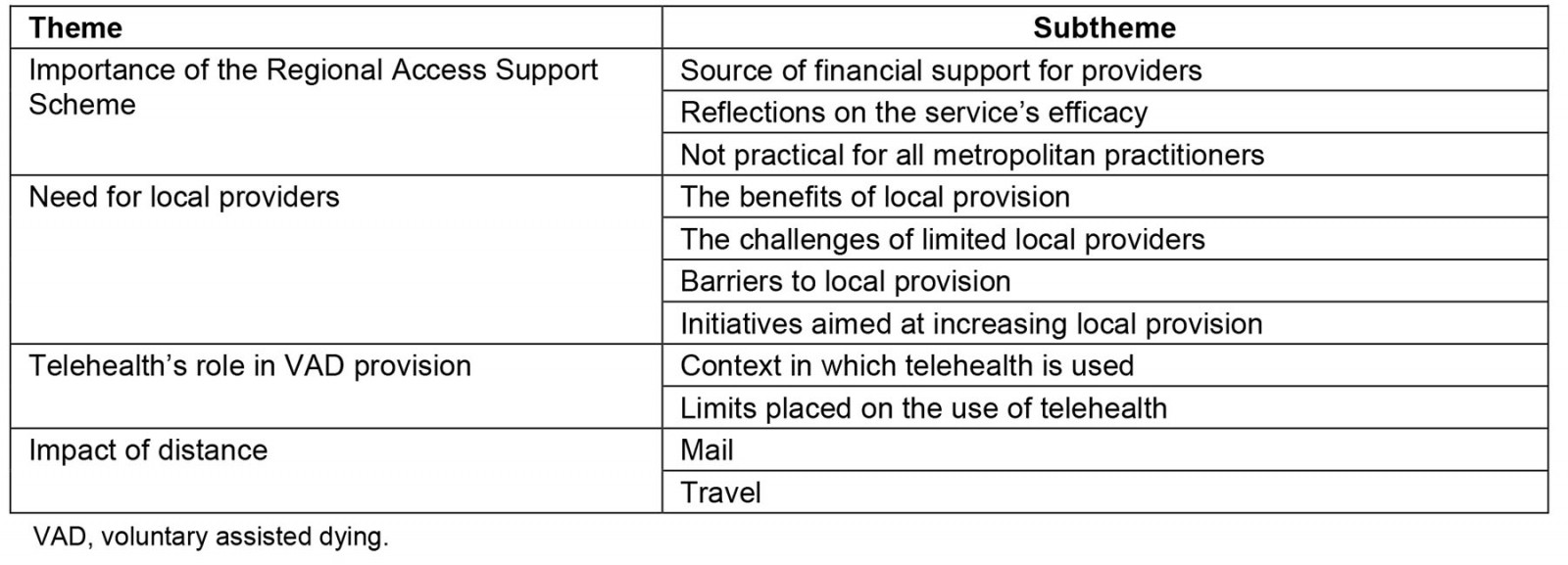

A total of 27 interviews with 29 participants were conducted (two interviews had multiple participants, and one interview was done in two parts due to participant availability). Interview times ranged between 58 and 144 minutes. Data analysis revealed four main themes: the importance of the RASS, the need for local providers, the role of telehealth in VAD provision and the impact of distance. Each of the main themes (and relevant subthemes) are summarised in Table 4 and described below, including as quotes from interview participants.

Table 4: Main themes identified through thematic analysis of stakeholder interviews

Importance of the RASS

The RASS was designed to improve access to VAD for patients living outside of metropolitan areas.

Source of financial support for providers: The RASS permits the provision for funds to be disbursed to support regional patients to access VAD.

The Regional Access Support Scheme can pay for a person to travel to a doctor. It will pay for a support person to travel with them, or it will pay for a practitioner to travel to the person, or everyone can travel and meet at a middle location that’s mutually convenient, and it will also pay for interpreters to travel … It will pay for things like accommodation, flights, that sort of thing, and it also pays for the practitioner’s time lost. So, [the VAD Care Navigators] can pay them as a set fee. It’s less than four hours or over four hours. There’s no kind of I was there for an hour and a half and it’s an hourly rate. [RS8]

The RASS is one of the limited opportunities for VAD practitioners to be adequately compensated, which was identified as critical in incentivising uptake.

It’s a fabulous service [and it] remunerates practitioners far more than they’re able to be remunerated doing work locally, but it requires of those practitioners significant time commitment and availability to fly to a region, do their assessment and fly back. [RS9]

The rural solution in WA would not have worked without the RASS on the current payment schedule. [HP6]

One participant commented on the reverse inequity that the RASS results in, identifying that the same resources were not allocated to palliative care.

It just seems to be so inequitable because we are having resources spent on sending people out to the regional areas to do assessments and getting the lethal substance out there, but we won’t get those resources being used for palliative care. [O7]

Reflections on the service’s efficacy: Participants who had engaged with the RASS were largely positive about it. Many highlighted that the RASS has largely served its policy purpose and embodied a commitment to person-centred care.

The [RASS] in WA has been a success in what it’s demanding. That issue of geographic equity is being addressed and we’re doing moderately well. [HP6]

[W]e’re dealing with patients getting near to the end of their lives, they don’t want to travel. They’re too sick to travel. Logistically it’s a … nightmare. There’s a whole host of reasons why that wouldn’t be possible for the person. And I think again that speaks to our practitioners, where they have been willing to do so, about the real need to provide that person-centred care. And for many people being at home in [their] own bed and not stuck in a hotel in [metropolitan WA] is actually a really huge part of that. [RS8]

Participants also indicated that the RASS was a well-managed and efficient system.

[T]hey organise all your travel, they pay for your travel and any food you need and that sort of stuff, and they’re very efficient and very flexible … I thought it was very good. [HP2]

One participant, while praiseworthy of the RASS, did suggest that it can create additional administrative burdens for practitioners.

So, it’s fine. It’s just the administration side of things that I’m not very good at … I don’t have any office staff, so I don’t have anyone who can actually put through bills for me. So, I had to make up my own billing invoice online. [HP5]

Not practical for all metropolitan practitioners: Despite the positive sentiments about the RASS, participants indicated that it was impractical for some practitioners due to the time commitment required. Furthermore, the success of RASS was perceived to be due to the availability of a subset of VAD providers.

I would consider doing that if it was paid more … I can earn money sitting here seeing my normal patients. I’m not going to rush down to [regional WA] and take a day off to do that when it’s so poorly paid, and it takes a long time. [HP4]

[I] have a little less flexibility because I have quite a lot of committed contract hours during the working hours of the week … [A subset of providers have] done lots of them … without [these] providers, we would be struggling to say we were providing equitable access to country areas. And, as you know, WA is a … big place. [HP6]

Need for local providers

Despite the positive reception of RASS, the scheme does not obviate the need for more local providers.

The benefits of local provision: Some participants described that the regional setting was conducive to VAD provision. The nature of such communities meant that regional health practitioners often had a pre-existing therapeutic relationship with the patient and professional relationships with local health service staff, which assists the process to operate more smoothly.

[What is] good [with] a hospital [in] [regional town X] is we’re fairly close to each other, we all know each other well. So, the boss of the hospital who’s my boss, I know very well personally, obviously, as I do the palliative care team, the pharmacist and the nurses on the wards who[m] the patient might need to pass through … [This] can actually make the process flow quite easily, which has been a massive advantage. I don’t know how I’d cope with that in a bigger city where I don’t know the hospital staff, and I don’t work in the hospital … Having that level of trust and working as a team has made things so much easier. [HP7]

[The] consulting practitioner is a visiting palliative care specialist who goes around the region. So, [they have] often met a lot of these patients. So, that makes things a whole lot easier when [they are] meeting someone via [videoconference], especially if they’re unwell, to be able to make a correct decision, but also, it’s easier in terms of the rapport from the patient’s perspective. [O1]

Local practitioners sometimes relied on informal ‘buddy systems’. It was observed by one participant that professional colleagues could provide eligibility assessments as consulting practitioners, while still satisfying the requirement for an independent assessment.

I got [the Care Navigator’s] advice … like being such a small place, we’re all friends. I [didn’t] want it to look like an inside job … I want[ed] it to look [like], from the ‘pub test’ [colloquialism for a hypothetical test of public reaction to an issue] so to speak, … an independent decision. So, I did actually ask the Care Navigator ‘Is this okay?’ and they said ‘Yes, it’s fine.’ [HP7]

The role of designated VAD regional leads and the importance of having one in each region were also highlighted.

I think because the regions operate very, very differently and distinctly … [it was] thought that [there should be] a regional contact across each of our seven regions, and that regional contact would be the person that, if there were any questions, would be able to answer and direct the person on to the appropriate service, which would usually be the Care Navigator Service. [RS7]

The challenges of limited local providers: Participants reported that there were challenges in meeting demands because of limited local providers (particularly in the early days). Consequently, local providers have been required to manage large patient loads, which has been found to be taxing on both the provider and the patient.

I'd sort of like to see that we had more practitioners available, just so that the singular general practitioner is not the sole practitioner of VAD. That might make things a lot easier, for [them] certainly, and perhaps also for availability for the patient. [O1]

The potential for inequitable access in towns that only have a single GP serving was also identified, particularly if the doctor is a conscientious objector. Such a context renders the importance of the statewide VAD services to facilitate referrals.

We have GPs that work alone in practice[s] in small towns all the way across the state … when you’re living in a town with one doctor … it can never be equitable. So, the Statewide [Care Navigator] Service … [is] so incredibly important to connect [a] person with someone that can assist them. [RS7]

Barriers to local provision: Participants identified that while there are several barriers that discourage practitioners from becoming VAD providers, additional barriers tend to exist for regional practitioners.

I think that rural practitioners may be busier and may just think, oh, I don't have time for this. [HP1]

Most of the practitioners are in small practices in country towns, and we've known from the outset that in those settings a lot of clinicians didn't want to be identified as Dr Death. [HP6]

A lot of them, as I found out from a situation in [Regional WA Town], are … new doctors, like perhaps recently from overseas, who actually do not qualify to do the training yet, they haven't spent the time in the Australian situation. So, some of them would love to and they just have to wait another four years until they're allowed to do the training. [HP1]

Initiatives aimed at increasing local provision: Participants reflected on the initiatives implemented to increase the number of local providers both pre- and post-implementation of the WA Act.

Pre-implementation measures Reflecting on Victoria’s issues with regional provision, the framing of the WA legislation aimed to widen the cohort of eligible VAD providers. Unlike in the Victorian regime, the WA legislation does not require one of the medical practitioners assessing the patient to have ‘expertise and experience’ in the person’s disease11, which has been interpreted as requiring one of the practitioners to be a specialist in the person’s disease. WA’s less prescriptive approach was favoured among participants.

I think in the Victorian legislation [one of the] practitioner[s] ha[s] to be in the same specialty as the disease of the patient … so if it was a neurological problem, they had to see a neurologist, if was a haematological problem they would have to see a haematologist. That's not always possible, particularly in the huge state that we have here. You know, if there is somebody up in … [regional WA], there isn't necessarily going to be a neurologist on tap that is interested in VAD. [HP4]

Moreover, unlike in Victoria, appropriately qualified and trained nurse practitioners are permitted to administer the VAD substance to an eligible person in WA. This innovation was intended to mitigate access issues by creating a larger pool of practitioners available to participate in this aspect of the VAD process13,14. However, only two nurse practitioners in WA have done the requisite training to date20. Some participants surmised that the lack of uptake among nurse practitioners was attributable to their limited role in the VAD process.

When the Act was drafted there was discussion about just allowing nurse practitioners to be part of the process in total. So, allowing them to do the assessments and to be a provider for a patient. And that kind of got watered down to, well, they can have the role of administering practitioner, and that'll help particularly in rural and regional areas. I don't think we've seen that. [RS1]

Participants suggested revising the role of nurse practitioners or implementing a GP–nurse collaborative partnership may be effective in addressing access inequities.

I think the way that [it could] work is if you had teams of, for example, GPs and nurse practitioners who would deal with a patient collectively. So, they're both there from the beginning, but the GP does the assessment bit … knowing that the nurse practitioner would be available for the administering role. Or [the legislation] needs to be revised so that nurse practitioners can actually do the whole process. [RS1]

Post-implementation measures Participants also reflected on the continued awareness-raising efforts undertaken by the WA Government to increase the amount of local VAD providers.

We did talk a lot about having a plan because we wanted to increase the number of people trained. We're doing a regional roadshow, for example, it's going around the regions, and [we’re thinking about] what incentives might well occur to encourage people. [RS3]

There is also evidence of payments being made to local providers for completing the mandatory training (using RASS funds), to incentivise provision. Initially, payments were only available when linked to a particular patient but have since been expanded.

[The WA Government] insisted that [practitioners had to] already have a case waiting initially … [but] because [of the] busy doctor's life, got a case here, got to do that training. We need[ed] them to train beforehand. So [the WA Government has] loosened up on that. [RS4]

Telehealth’s role in VAD provision

The Commonwealth Criminal Code (CCC) places some restrictions on what aspects of the VAD process (and related communications) can occur electronically4,5,12. The legislation and guidance issued in WA is that telehealth can be used for some aspects of the VAD process (subject to the constraints of the CCC)12. Participants reported that telehealth was used in the VAD context to some extent.

Context in which telehealth is used: Many participants identified that permitting telehealth for some aspects of the VAD process was useful.

One of the key aims of the WA legislation was to minimise the restriction on access that would occur for rural or remote patients. I think that the ability to have videoconference interactions has achieved that goal as much as you can without a million practitioners around WA doing this. [HP3]

Telehealth was often used in consulting assessments and was occasionally used by coordinating practitioners for some aspects of the VAD process (insofar as permitted). In many cases, telehealth was used in conjunction with the RASS to help minimise travel time.

What I have tended to do there is take a first request and first assessment by videoconference … and I have access to that sort of seven days a week … I've tended to … then travel to see them for the final request ... The Navigator Service and the Regional Access Support Scheme have made that very easy. [HP3]

Limits placed on the use of telehealth: Many participants reflected on the challenges that arise in practice due to the CCC.

While we can talk about some stuff … over audiovisual connection, there are some [stuff] that can only be covered face to face. So, until that changes, we'll always be making two visits to [regional WA] for one person … I mean I do think at some point … you probably do need face to face … because these are such important discussions to have and the things that people want to tell you and ask you are so important. But when you're talking about a state as big as WA and somebody might be three-and-a-half hours' drive from where we are, it's just not practical to do that every time … it would be simpler if that was changed. [HP1]

[The Commonwealth Criminal Code is] exceptionally challenging, particularly for some of our rural patients, to wait for a hard copy prescription which can't be scanned [and] emailed like a standard prescription. [RS10]

Impact of distance

Participants reflected on the fact that the vast geography of WA created logistical difficulties and delays.

I think there will always be challenges for WA given its … population distribution geographically in terms of getting to the country and remote areas. [O6]

Mail: Participants reflected that the need to use postal mail introduced delays. However, postal mail was necessary on occasions because certain documentation (such as a prescription or protocols) are unable to be transmitted electronically because of the CCC.

When you live regionally, everything takes at least another 24 hours. So, if you lived in the city, I'm sure everything would be done in a way shorter timeframe ... Even if it's … [a] priority post that's coming from a regional area to the city, that's not going to happen overnight. [O1]

[W]hat we've found … is often when sending an item from one rural location to another, it will need to go from a rural area, back to [Metropolitan WA] and then back out again. We've seen that with mail, we've seen that with medications. [RS10]

Travel: Due to distance concerns, various personnel involved in the VAD process (eg health practitioners, Statewide Care Navigator Service and Statewide Pharmacy Service) would often need to fly to a particular region. This was quite demanding, due to the paucity of available flights and the flexibility this necessitates.

When it comes to flights, particularly with the scarcity of flights to some areas, it has been challenging to meet [the patient’s] desires in some of those situations … Often practitioners and patients have been very flexible, which is great. [RS10]

Some participants described that VAD personnel would often commit to late-night/weekend commutes. In some cases, long drives were required in the absence of flights.

There was a patient in [regional WA] for whom, because the team could not get a flight, the practitioner and the Care Navigator drove 1,900 kilometres over a weekend to support the administration to the patient because that's when the patient wanted to have it … [T]here are some amazing stories of commitments, focus on [a] patient[’s] wish, dealing with logistic nightmares … [The VAD Care Navigator] must have travelled a million kilometres already in my view. [HP6]

Discussion

This article reports on early reflections of regional VAD provision and access in WA. The findings suggest that active efforts taken by the WA Government to facilitate access during the law-making and implementation phase of the WA legislation have, at least to some extent, been successful. Most significantly, participants emphasised that the RASS has been instrumental in facilitating regional access, and participants were largely complimentary of its operation. Other examples of initiatives that have facilitated access include the removal of the ‘expertise and experience’ requirement and facilitating greater use of telehealth.

Notwithstanding the positive reflections, the findings did identify challenges with regional provision. Consistent with the Victorian experience2, the lack of local providers was considered by participants as a barrier. It is concerning that, although each region has had requests for VAD, not all regions have local providers18. It is promising that the number of local providers has increased over time, and the government is taking active measures to raise awareness and incentivise practitioners to become VAD providers, but there is still a dearth. Although the RASS can facilitate VAD provision, there were sometimes delays due to practitioner availability and travelling constraints. Furthermore, if it is the case that the RASS is largely serviced by a small subset of VAD providers, this raises concerns about the scheme’s sustainability. Increasing the number of local providers will inevitably reduce the reliance on the RASS and likely reduce delays.

The findings also suggest that some of the early challenges faced by regional communities may be addressed through law reform. Most significant are the challenges that arise due to the CCC. While participants largely found the use of telehealth to be beneficial, restrictions on its use were considered unnecessarily burdensome, which is consistent with the Victorian experience10. Similarly, the requirement to mail particular documents (eg prescriptions, protocols), due to the CCC’s prohibition on such documents being emailed (or transmitted by other electronic means), was described by participants as burdensome due to the inevitable delays it caused. The sentiments from participants largely echoed calls for reform of the CCC4,5 (including those from the WA VAD Board18) to remove such challenges.

Participants also identified areas for reform in relation to nurse practitioner involvement. Internationally, the ability for nurses to participate in VAD provision has been identified as a mechanism to address some access barriers, particularly in the context of limited providers in rural settings1. Several participants suggested that low nurse practitioner involvement could be in part attributable to their role being confined to acting as an administering practitioner (unlike in Canada, where nurse practitioners can also undertake eligibility assessments). Given this initiative has not been successful to date in WA, further reflection is needed to increase nurse practitioner involvement with VAD.

Finally, although most participants identified significant challenges for residents of WA accessing VAD, there are opportunities to use strengths of regional health care to enhance access. For example, participants identified the benefits of personally knowing other medical practitioners and health administrators in the local area. There may be scope to harness these existing relationships to establish local networks to support access to VAD.

Limitations

First, although this study includes the views of a variety of stakeholders, there were ultimately limited participants in each group, and therefore data saturation was not reached and hence some perspectives may not have been captured by this study. Second, not every participant was able to reflect on the regional experience, so the findings reported in this article are limited to a subset of the sample. We note that although three participants were themselves based in regional WA, others interviewed were able to meaningfully comment on these issues. For example, five out of the six interviewed VAD metropolitan medical practitioners travelled to provide VAD regionally. Similarly, many regulators and VAD system personnel had active roles in regional engagement to enhance access. Finally, as some of these findings relate to WA-specific initiatives, the results may have limited relevance to other settings.

Conclusion

This article has provided an overview of the early operation of VAD provision in regional WA. The findings suggest that although there have been several successful initiatives that have helped to facilitate regional VAD provision, challenges to equitable access remain. Efforts intended to incentivise local provision need to be sustained, and consideration needs to be given to areas of reform that can help address some of the perceived barriers to regional provision. Further research needs to be undertaken to monitor regional provision over time.

Funding

This research is co-funded by the Australian Centre for Health Law Research, Queensland University of Technology and Ben White’s Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (FT190100410: ‘Enhancing end-of-life decision-making: optimal regulation of voluntary assisted dying’).

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose that Ben White and Lindy Willmott were engaged by the Victorian, Western Australian and Queensland governments to design and provide the legislatively mandated training in each of these states for medical practitioners (and nurse practitioners and nurses as appropriate) involved in voluntary assisted dying. Casey Haining was employed on the Queensland project. Lindy Willmott is a member of the Queensland Voluntary Assisted Dying Review Board.