Introduction

Health education is key to improving the health conditions of vulnerable populations. According to the WHO1, by increasing knowledge, influencing motivation and improving health literacy, health education equips people to make more autonomous decisions relating to their health and to adapt to changing circumstances. Furthermore, the importance of health education lies in its capacity to enable people to take action to address the determinants of health1.

Infectious diseases associated with poverty usually affect rural populations with limited access to health care. In Latin America, cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) represents a challenge because of its epidemiological, clinical, and biological complexity. In Colombia, which reported the second-highest number of cases in the region in 2020 (6161)2, a collective effort to achieve effective prevention and control measures is needed.

Capacity building is a set of educational processes that strengthen skills for the wellbeing of communities and generate changes to traditional ways of solving collective problems, which allows for communities’ continued autonomy over time. This development of skills enables communities to make better decisions in their daily lives in relation to health as well as to their own conception of wellbeing, contributing to the sustainability of health interventions3. In this way, capacity building can help mitigate several barriers that affect the management of these infectious diseases, by strengthening the social capital of communities, empowering them and advocating for social transformation at the local level4. This article presents the learning process of implementing a capacity-building program, which sought to give tools to the community to improve CL prevention and control in the municipality of Pueblo Rico (Colombia), which is an endemic area of CL.

Pueblo Rico is in the Risaralda region, in a transition zone between the Andean region and the rainforest of the Colombian Pacific. The population mainly affected by CL are people who live in the dispersed rural area, which corresponds to 99.96%5 of the 632 km2 of Pueblo Rico’s territory6, and which is inhabited mainly by Indigenous people from the Embera community and Afro-Colombian people. These communities have the highest levels of poverty in the municipality, and they have been severely affected by Colombia's armed conflict. In health matters, these isolated rural settlements face access barriers due to their dispersed rurality and limited health infrastructure. There are important determinants of health related to environmental factors linked to the tropical rainforest ecosystem, cultural factors related to life practices that affect health, and socioeconomic factors derived from social exclusion and poverty7.

In previous community-based studies7,8 in CL developed by Centro Internacional de Entrenamiento e Investigaciones Médicas (CIDEIM), it was evident that without building capacity in the communities, it was impossible to improve the prevention and control of infectious diseases; also, it was identified that there were significant learning and cultural barriers related to understanding health issues and there were limitations when it came to the population’s social skills. These reasons motivated the development of a pedagogical program according to the sociocultural characteristics of the population that could facilitate the comprehension of CL topics and contribute to the development of social skills to facilitate the transfer of knowledge. In response to that, innovative methods were included in the design, implementation and evaluation of this program to propose more effective alternatives to traditional learning methods.

Contextual analysis9 conducted in Pueblo Rico by ethnographic methods allowed the research team to choose three key actors to participate in a capacity-building program: health workers because they implement the programs to prevent and control infectious diseases in the municipality; local leaders because they live in the rural villages, and this allows them to closely monitor the patients or possible cases and they are also trusted by the community; and high school students because they are the ones who transfer the knowledge to their families, and they are also the new generation who can internalize good health practices.

The objective of this article is to evaluate the implementation of the pedagogical model, the results of the learning process and the impact of a capacity-building program in CL conducted in the municipality of Pueblo Rico, and to analyze its contribution to the improvement of infectious disease prevention and control capacities in rural communities.

Capacity-building program in cutaneous leishmaniasis

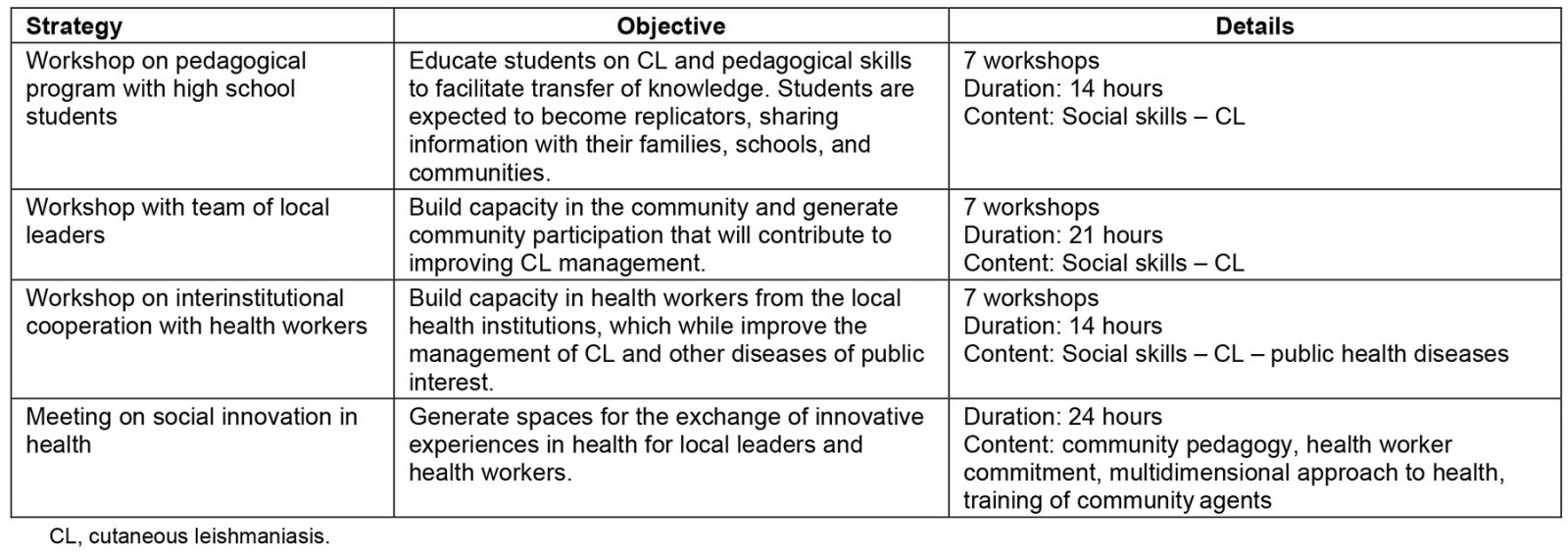

The program consisted of 21 workshops (February–October 2021) and a meeting on social innovation in health (SIH) (26–28 October 2021) (Table 1). The main topics of the workshops were CL knowledge and knowledge about other diseases as requested by health workers; social skills were also included to facilitate the transfer of knowledge.

The program was designed using an experiential methodology10 that favored practical learning and allowed participants to link the knowledge learned to their own context. The methodology was adjusted for each group of participants and playful pedagogical tools11 were used to transfer technical health knowledge, making it understandable to people with different education levels. Descriptions of strategies, content, and products is compiled in an online resource12, to facilitate public access to the information.

Table 1: Strategy and participants of the capacity-building program

Methods

Participants

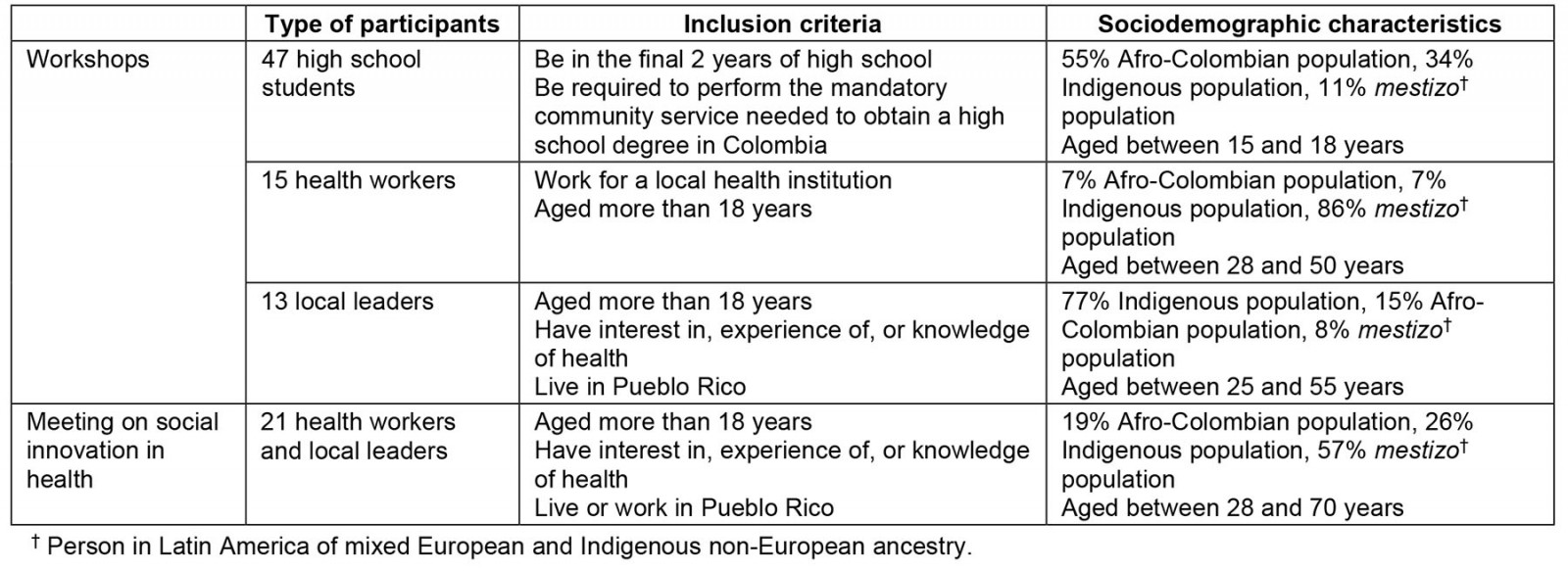

The program had 75 participants in the workshops and 21 participants in the SIH meeting, who also performed the evaluation. It had three types of participants (Table 2): local leaders, who were selected with the help of social organizations, local authorities, and a field coordinator; health workers, who were designated by the local health institutions; and students, who were designated by the local high school. The program took into consideration the diversity of the participants in terms of ethnicity, gender and age.

Table 2: Information about the participants of the evaluation

Data collection

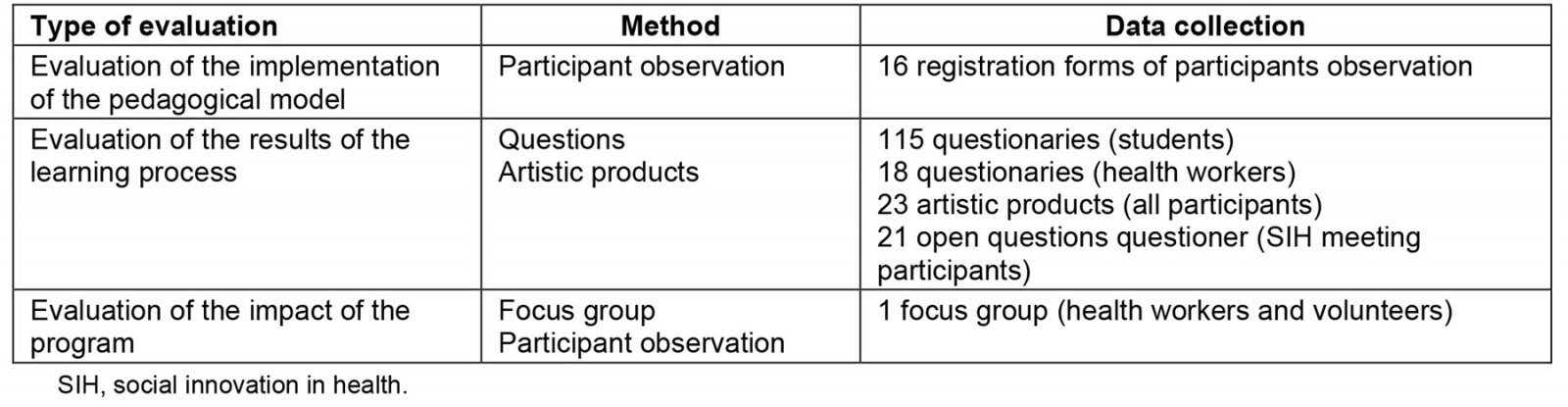

Primary data were collected for three types of evaluation, using mostly qualitative data (Table 3). They were an evaluation of the:

- implementation process, through participant observation conducted by the research team after every field trip, which evaluated the implementation of the pedagogical model to make necessary adjustments during the process

- results of the learning process, through multiple-choice questions applied after some workshops to high school students and health workers; through the development of artistic products to facilitate the appropriation of knowledge at the end of the workshops by participants; and through open-ended questions during the SIH meeting

- impact, conducted through a focus group with health workers and local leaders at the end of the program.

Table 3: Types of evaluation, methods and data collection

Coding and analysis

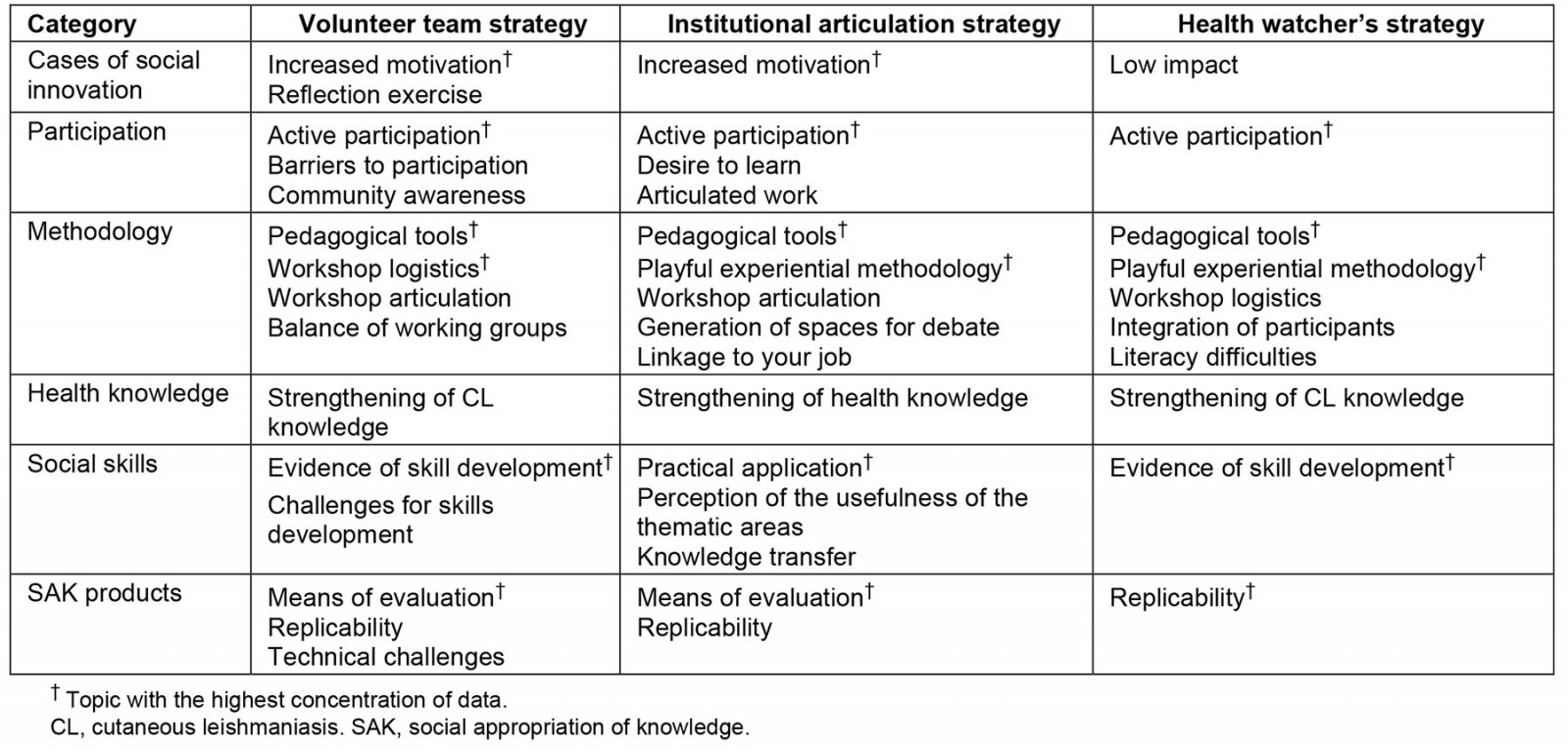

The qualitative data that resulted from the participant observation of the research team (Supplementary table 1), the focus group with the participants (Supplementary table 2) and the open-ended questionnaire completed by participants of the SIH Meeting (Supplementary table 3), was coded using Nvivo v12 (Lumivero; https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo) and analyzed conducing thematic analysis based on three analysis categories:

- social appropriation of knowledge, a process in which the people of a community voluntarily incorporate the learning of a formative experience in situations of their daily life13

- SIH, creative and affordable solutions to address health needs, especially in contexts of vulnerability and inequality14,15

- meaningful learning, the participatory acquisition of new knowledge and the development of critical awareness, that is connected to previous knowledge or experiences of the person learning and to the context they live in, which facilitates its application or usage16.

The quantitative data that resulted from the multiple-choice questions were pooled and quantitively coded, and a quantitative analysis was developed (Supplementary figs1,2).

To ensure the truthfulness of the data, three different types of participant (student, local leader and health worker) evaluated the program. These participants were selected through a process with local organizations and authorities, and a constant reflexivity exercise took place by the research team, which was made up of four researchers with different backgrounds, but with experience in social and qualitative research and work with vulnerable populations. To ensure consistency, the methods used in the capacity-building program, such as the use of audiovisual materials and meaningful learning, were chosen on the basis of scientific evidence that shows their impact on health literacy and their effectiveness in increasing health knowledge17-21. Considering the nature of the qualitative research, the findings and main points of the discussion may be applicable to health capacity-building programs focused on vulnerable populations, and ethnic or culturally diverse groups, in comparable complex sociocultural contexts where structural problems affect health as well as the execution of implementation programs.

Ethics approval

To carry out all proposed activities for this study, informed consent was obtained from all participants involved. Similarly, the research was approved by the CIDEIM Ethics Committee (1272).

Results

Evaluation of the pedagogical model’s implementation

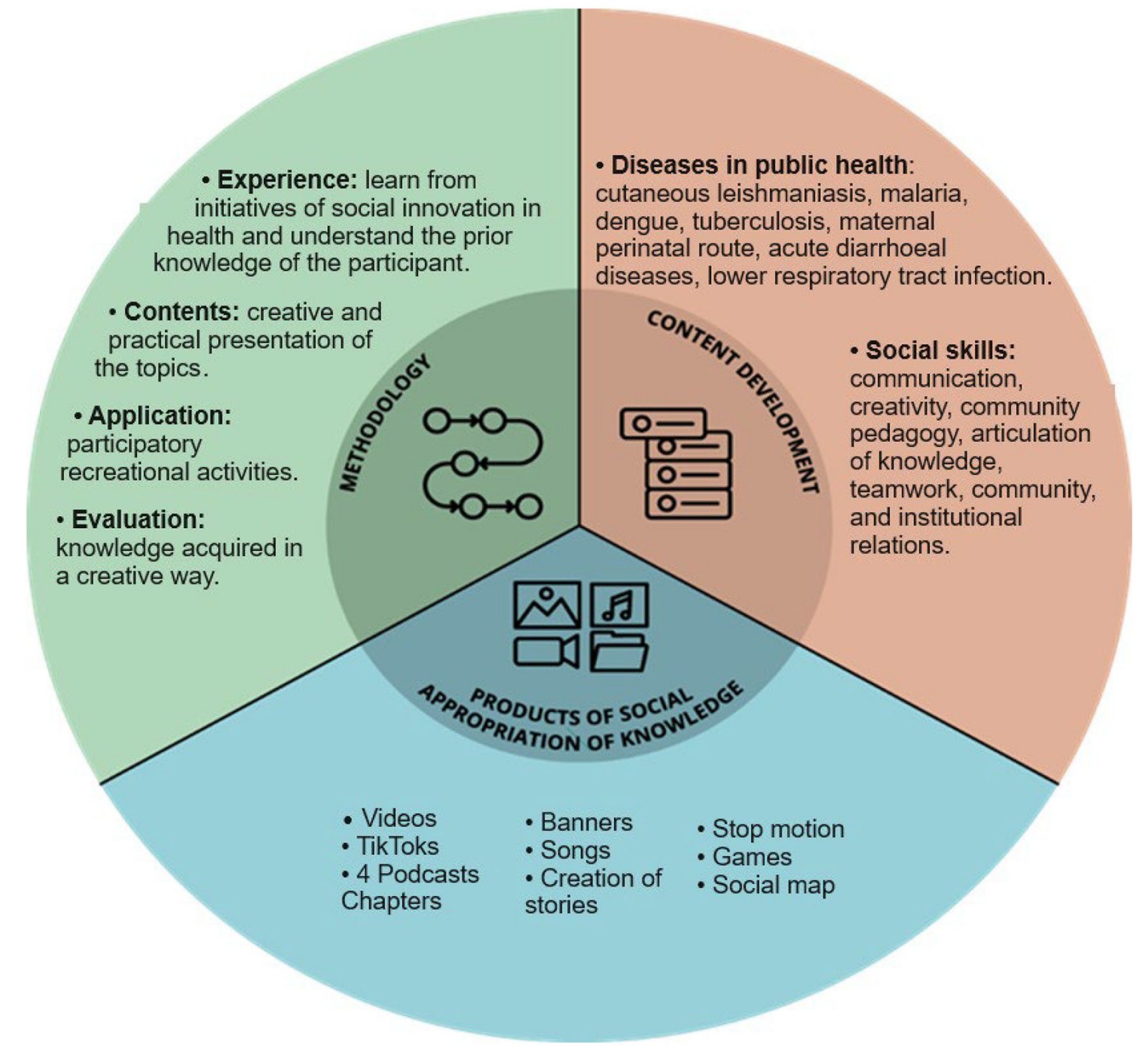

The pedagogical model used was structured and adjusted based on a constant exercise of reflexivity, which is why its development is considered a result of the implementation process. The model developed (Fig1) followed four main steps:

- Experience: audiovisual material was used to show SIH cases that served as inspiration.

- Content development: pedagogical tools were used to reinforce understanding of health topics and social skills.

- Application: what was learned was put into practice through playful activities that facilitated appropriation.

- Evaluation: participant-centered evaluations were designed to determine the knowledge acquired during the workshops; for students, there was a written multiple-choice evaluation, for local leaders there was an innovative evaluation method based on the development of artistic products, and for health workers, there was a mix of both types of both types of evaluation.

Figure 1: The pedagogical model of the capacity-building program.

Figure 1: The pedagogical model of the capacity-building program.

The pedagogical model was based on a collaborative exercise in which the research team contributed theoretical bases, and, through discussion and practical exercises, knowledge was transformed and enriched by the experiences and perspectives of the participants. While the participants learned about social skills and CL, the research team learned about effective work with communities, the sociocultural adaptation of specialized knowledge, the experiential dimension of the disease, which was essential to evaluate many of the prevention and control measures proposed from the biomedical perspective.

The pedagogical strategies and tools used in this model were adapted to respond to the characteristics of the three target populations, in terms of levels of schooling, language barriers, and learning styles. This adaptation was the main factor that contributed to the success of the program. According to the research team's evaluation (Supplementary table 1), in terms of pedagogical strategies, for health workers, linking the thematic content with their work in the territory resulted in greater interest and understanding of the benefits of the workshops by the participants. For the students and local leaders, constant reiteration of information was necessary for the appropriation of knowledge; and balancing work groups helped ensure equal participation.

For all participants, the use of playful experiential methodologies and audiovisual tools facilitated comprehension of the theoretical content:

The use of images in the explanation of theoretical content in health allowed them to understand it clearly … It was evident that they [the leaders] have good memory and retention of the images … (Evaluation of Workshop 4, research team, July 2021)

Likewise, practical exercises and playful activities were adapted to the learning style for each participant. With the health workers, it was observed that while they began with a skeptical attitude towards the usefulness of this knowledge, they recognized the applicability of it in their work with communities. In the case of the students, who are mostly Afro-Colombian, the research team’s evaluation noted an ease in social skills, and they enjoyed the use of technology and dynamic activities, while the Indigenous participants demonstrated more discrete participation. Regarding local leaders, while there was a relevant strengthening of social skills, they required further engagement, since many of them possessed less developed social skills:

It is important to keep in mind that creativity is a very underdeveloped skill in this group, and they have a limited use of tools, therefore, community pedagogy will be a topic that will require much more deepening. (Evaluation of Workshop 5, research team, August 2021)

A key element of the program was the use of SIH experiences in similar contexts as inspirational examples, which led to an increase in the motivation and commitment of the program’s participants to participate in health. According to the research team’s evaluation (Supplementary table 1), the SIH experiences that were shared with the participants increased participants’ motivation to work towards the wellbeing of their community, slowly changing their pessimistic and passive attitude towards their municipality’s health problems by showing them possibilities for transformation. Nonetheless, it was also identified that for these SIH experiences to be effective, it was necessary to implement a reflection exercise guided by the facilitator in which central elements, achievements, and similarities with Pueblo Rico were identified, to facilitate a deeper understanding of the experiences. With the local leaders, a more in-depth guided reflection exercise was necessary due to some of the communication barriers:

The presentation of a SIH is useful, but it requires a reflection exercise. If you only narrate or show the video it does not work ... a strategy was designed to read and verify paragraph by paragraph that facilitated an understanding of the experiences. (Evaluation of Workshop 2, research team, April 2021)

Regarding limitations, participation was affected by contextual factors that made it difficult for people to consistently participate in the workshops, as mentioned in the following fragment:

The participation in today’s workshop was low, but, external factors must be considered, since the rain makes it difficult for participants to find means of transportation, and a lot of them have to walk long distances or they use motorcycles to get to the workshops. (Evaluation of Workshop 2, research team, April 2021)

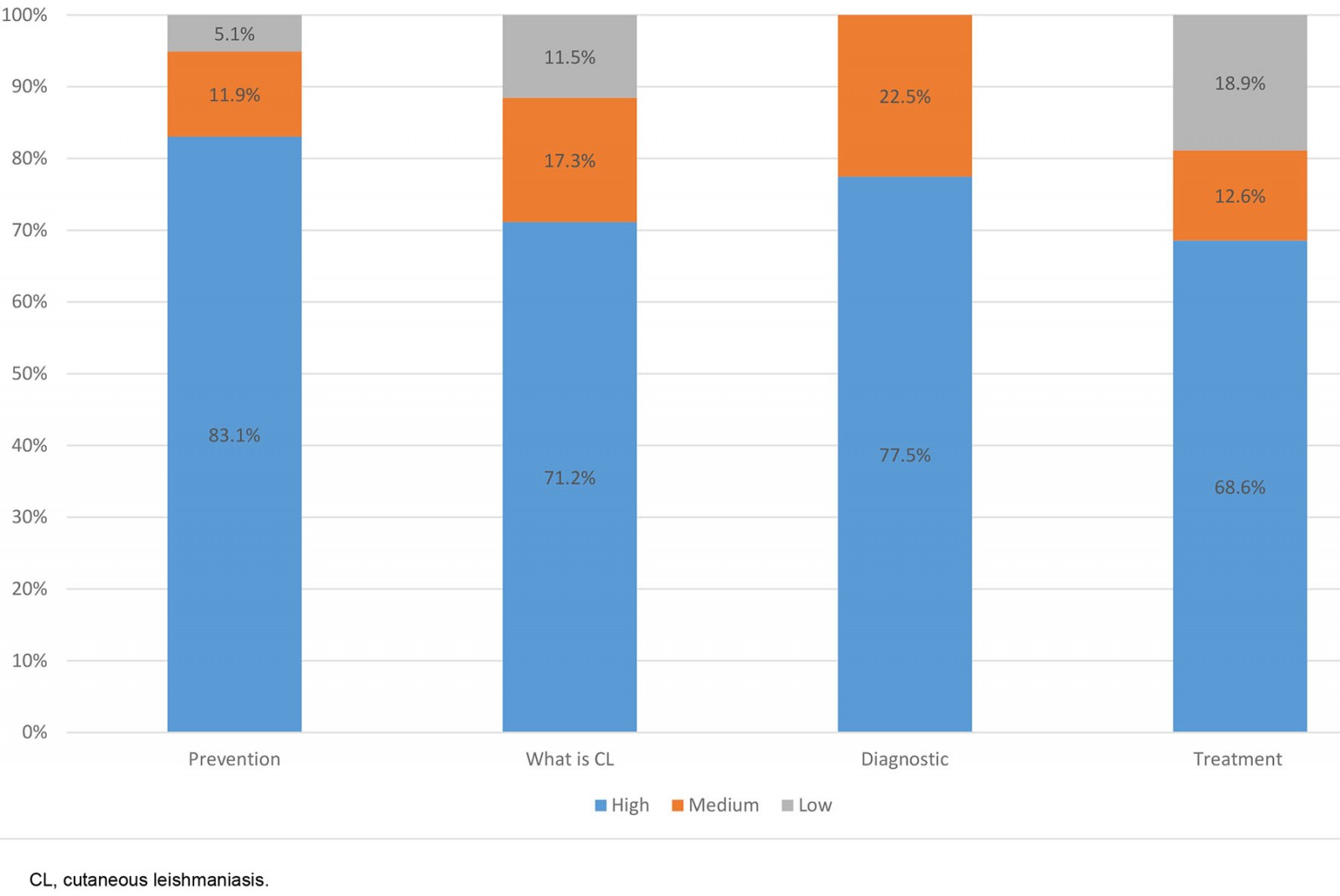

Evaluation of the results of the learning process

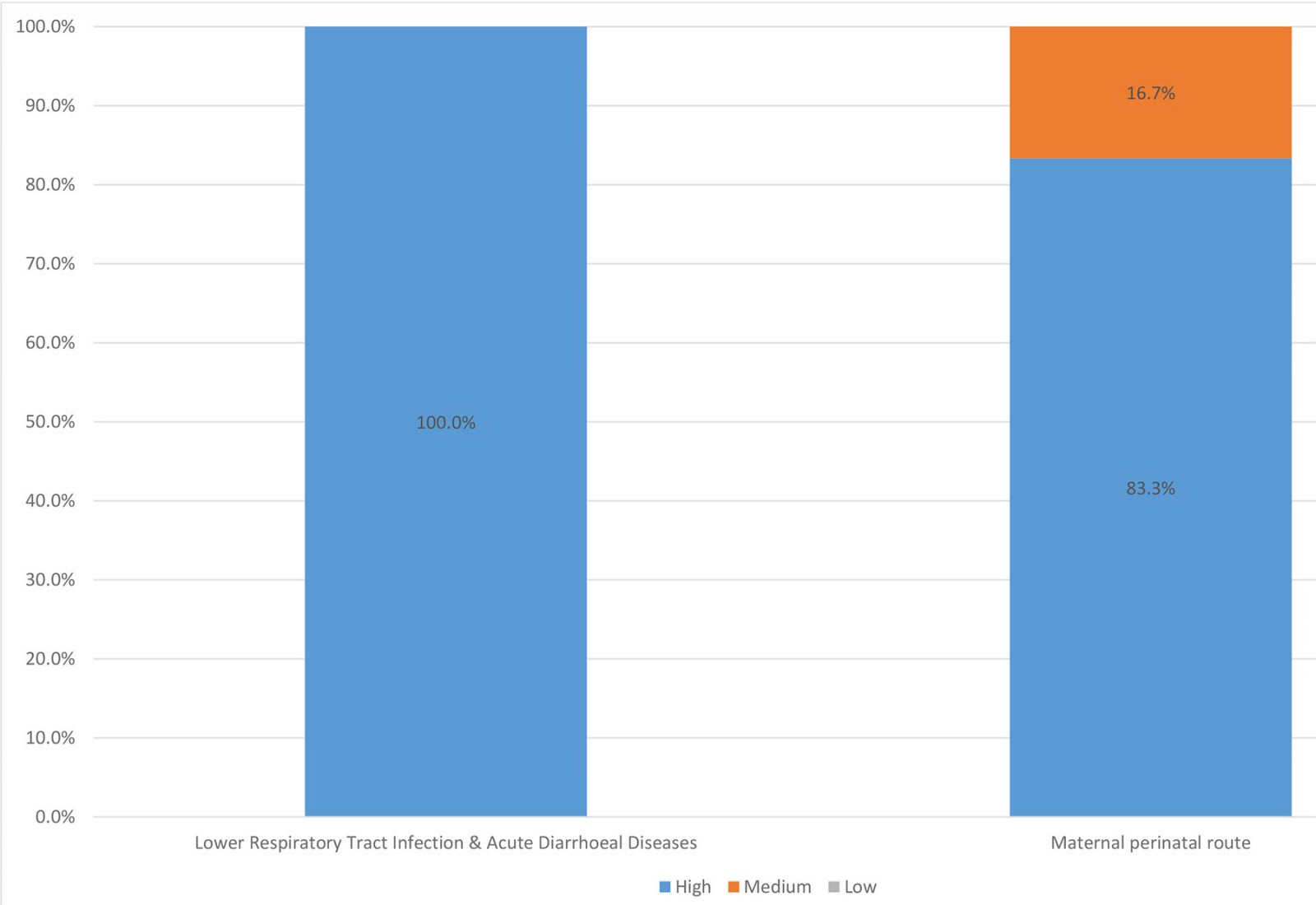

The results of the learning process were evaluated by two different methods. A traditional evaluation using multiple-choice and open-ended questions, which showed positive results in terms of acquisition of knowledge. With the students, the questionnaires applied on the four main topics of CL showed that 68.4–80.5% of the students had a high level of learning, 14.2–22.5% had a medium level of learning, and 5–17.1% had a low level of learning (Supplementary fig1). Likewise, with health workers, the questionnaires about the diseases covered in the workshops reflected that depending on the subject 66.4–100% of the health workers had a high level of learning, 16.6% had a medium level, and none had a low level (Supplementary fig2).

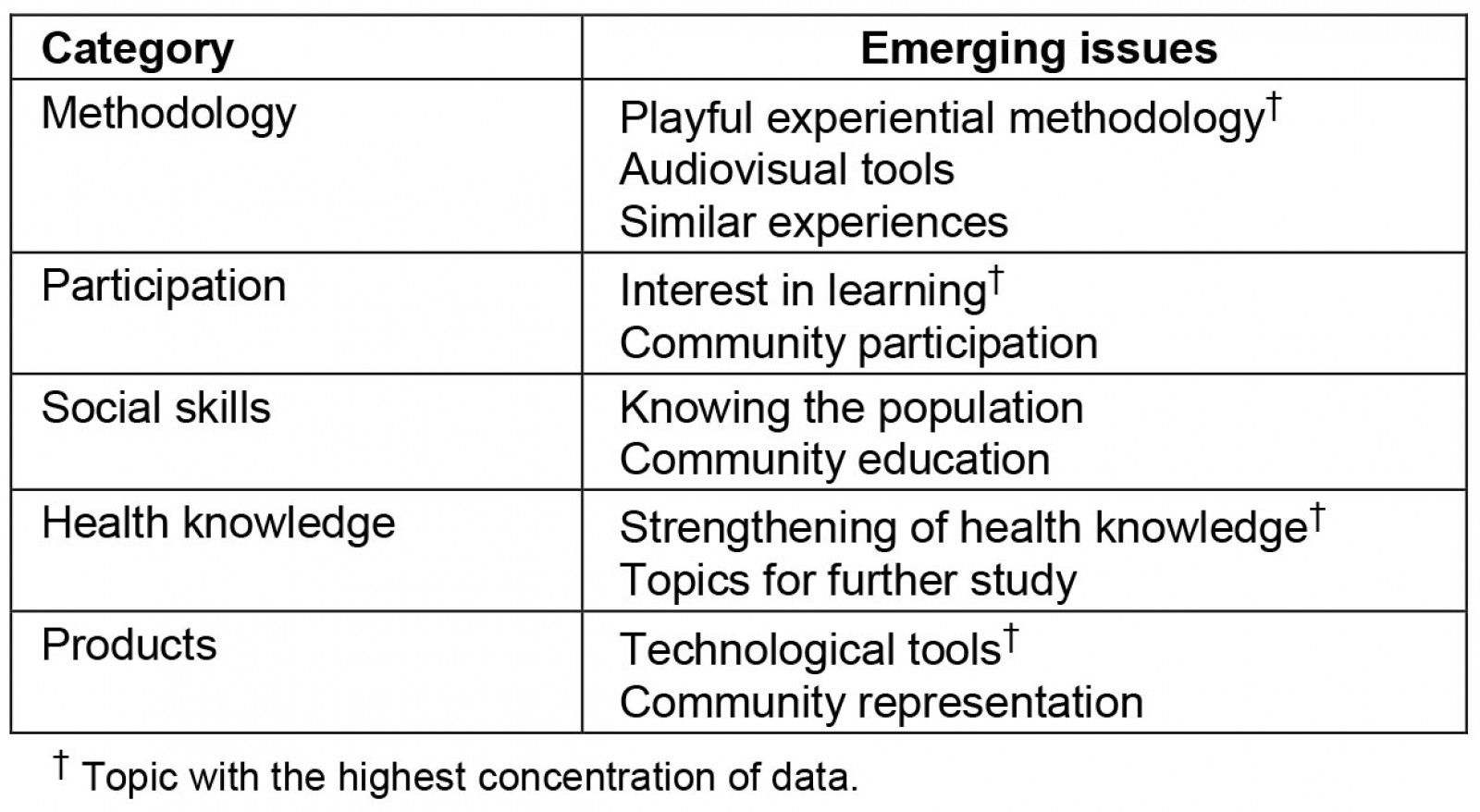

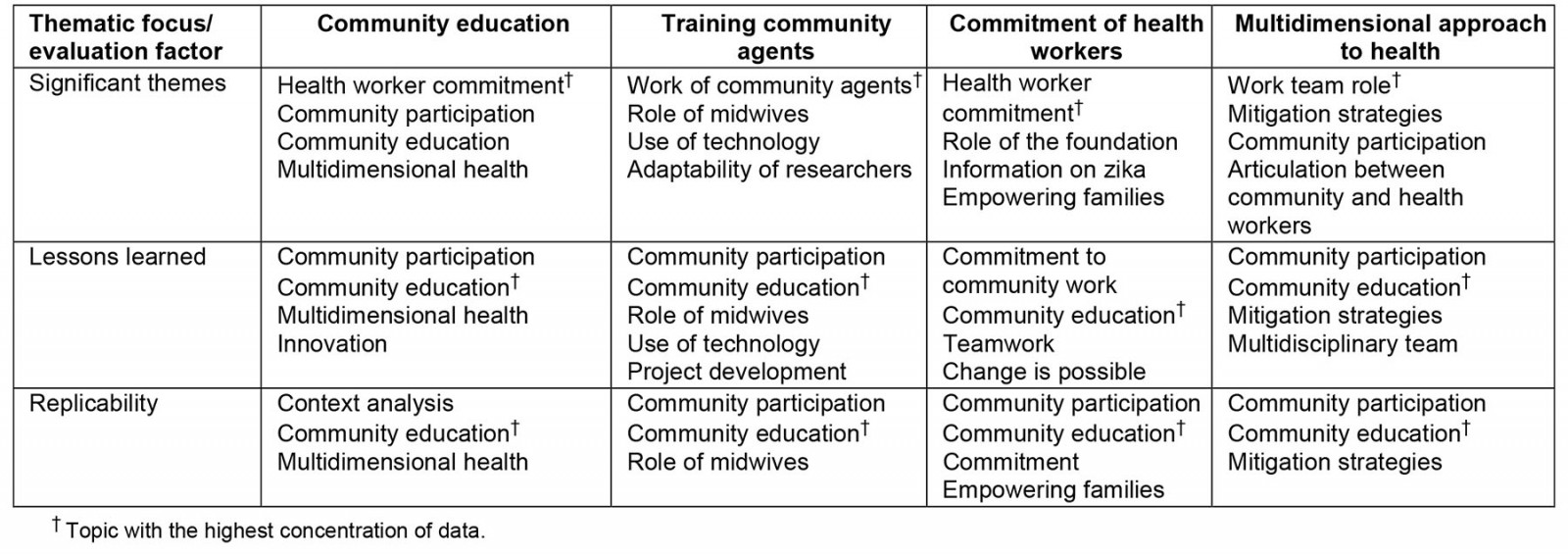

In terms of the results of the SIH meeting, the participants’ evaluation showed that they recognized the importance of learning about other community health experiences by interacting with people from other municipalities and learning about national and international SIH initiatives. To the participants, the main lessons learned from these initiatives were the important role of health workers and community agents, in particular, their commitment and the impact that it has on communities. These lessons were particularly important because of the motivation that they provided for health workers and community health leaders, as is evident in the next quote:

The meeting was excellent, it allowed the exchange of experiences which reinforced the love and dedication to community work. (Questioner, participant of SIH meeting, 28 October 2021)

The participants also underlined the importance of health education as one of the main takeaways from the SIH meeting. Some of the points they mentioned about this subject were the importance of raising awareness in the community about prevention and control of diseases; the need to use playful methodologies that are appropriate to work with communities and that facilitate their comprehension of information; and the need for community health education to be accompanied by real changes and community empowerment.

The second method of evaluation was innovative, and it was based on the development of artistic products by local leaders and health workers. The research team’s evaluation showed that these products were interesting and innovative ways to strengthen the knowledge acquired, since their elaboration required recalling, summarizing, and communicating what was learned (Supplementary table 1). They also acted as a creative means of knowledge replication with the community. Nonetheless, the development of the artistic products involved significant challenges as the participants’ ability to use technological tools varied, and constant support from the research team was necessary.

This method also showed positive results with respect to acquisition of knowledge. The research team observed an increase of health knowledge (Supplementary table 1) about CL, as well as other public health diseases, which was reflected in the evaluation exercises and the artistic products elaborated:

During the recording of the podcast, the understanding of the CL treatment was evident, as the leaders were able to communicate the topics with a clear discourse ... (Evaluation of Workshop 5, research team, August 2021)

The research team’s evaluation revealed that participation in the workshops allowed the local leaders to recognize the need to encourage the community to take a proactive attitude and work towards co-responsibility in health. In the case of health workers, raising their awareness helped improve their perception and the way that they engaged with the community. They were also able to identify other colleagues working within the municipality, with whom they could form collaborative relationships:

As the participants get to know each other, one can see the idea of a network of people working in health consolidating, sensitive to the possibilities of generating strategies for the improvement of the quality of life of their communities. (Evaluation of Workshop 5, research team, August 2021)

Still, the elaboration process for these artistic products sometimes reflected knowledge gaps or different levels of comprehension of certain topics, but since this process was always done in groups of participants and not individually, and they were always monitored by the research team, developing the artistic products often allowed for these gaps and differences to be addressed, as mentioned in the following quote:

During the development of the flyer, the group was divided in two, generating a process of reflection about the health topics addressed during the workshop. In some cases, some participants forgot some aspects, but they were complemented by the other members of the group. (Evaluation of Workshop 4, research team, July 2021)

In terms of limitations, the systematization of the artistic products that were developed as a means for evaluation represented a challenge, which led the research team to conclude that additional traditional written evaluations are necessary. But these evaluations must be adapted according to the characteristics of the population to make them feasible; for example, using images in multiple-choice questionnaires.

Evaluation of the impact

In the participants’ evaluation, health workers and local leaders recognized that they had strengthened their health knowledge through the formative processes, especially on CL, and they highlighted that this was important because it allowed them to contribute to the improvement of preventative measures and the control of the disease in their communities:

... what has caught my attention is the knowledge that we are acquiring, because there are things that I did not know about leishmaniasis. So, they have given us many tools to take to the community and prevent diseases like these. (Focus group 1, health worker, 28 October 2021)

In terms of social skills, the participants’ evaluation revealed that health workers understood the valuable of learning skills that can be applied for community education, especially for transferring knowledge to the community in a way that it’s easy to understand, since most of them are in charge of health education as part of their jobs. This is evident in the following quote:

... What I liked most about the project is being able to synthesize the concepts and be able to provide them to the community in an easier way, because in our area, the focus is health education and this has allowed us to reach communities more easily in our surveillance programs. (Focus group 1, health worker, 28 October 2021)

The participants agreed that the pedagogical strategies and tools used as part of the pedagogical model of the program were inspirational examples that they could replicate in their jobs, particularly for health workers. That they could identify the usefulness of the lessons learned for their work is evidence of the awareness-raising process carried out, and the appropriation of the social skills, and is an important contribution of the project.

… What I liked the most is the didactic way in which we have learned, because sometimes we forget a little that it is an easier way of learning and that it is something that we can implement both for ourselves, and for communities in general. (Focus group, health worker, 28 October 2021).

Likewise, participants considered that the artistic products were valuable tools for articulating information concisely and transferring knowledge to the communities:

The TikTok … allows to see the uses of technology to replicate knowledge, from what you taught us we use the most concrete [to make the TikToks]. (Focus group, health worker, 28 October 2021)

Moreover, the participants emphasized that these products were particularly valuable because the community was represented in them due to the use of Indigenous and Afro-descendant characters in the videos, the creation of a song in the Embera language, and the use of real anecdotes for the dramatizations.

Regarding the SIH initiatives, the participants considered that they have an important value, because they illustrated that despite resource limitations and difficulties similar to those observed in Pueblo Rico, health workers and local leaders in Colombia and the world work for the health of their communities and have achieved positive results. Participants realized that transforming health conditions in their communities was possible and they identified strategies that could be replicated in their territories.

I was so impressed by Doña Carlota’s project [an SIH case], because that is the empowerment that must be taught, she says she teaches them with what they have, she has not given them anything. So that is what community work should be like, with what they [the community] have they can improve. (Focus group, participant of meeting, 28 October 2021)

Lastly, another valuable impact of the program is that participants showed an interest in continuing to participate in future training projects, which would allow them to further contribute to their community:

Future projects are welcome because they strengthen the communities. Pueblo Rico needs a lot of training and support; so, this is an opportunity to strengthen the communities through these processes, since in the end they are the ones that will benefit ... (Focus group 1, health volunteer, 28 October 2021)

Discussion

To achieve effective capacity building, there were three key elements in this program. The first element was the application of the principles of meaningful learning22. In the pedagogical design, the linking of the knowledge conveyed with the experiences of the participants, the use of pedagogical tools according to the needs of the participants, the identification of the skills and learning styles of the participants, the suggestion of innovative methodologies, and the reflective exercise of the research, facilitated the acquisition of knowledge, as well as recognition of its usefulness and applicability. Moreover, the participatory approach, which is one of the main principles, increased the impact of the project because it helped foster more active participation of local leaders and students in health processes. In the long term, this can help improve the health conditions of the community, as it increases the probability that the community and institutions will become involved in health promotion and that there will be changes in the power relations between them.

The second element was the use of SIH case studies. These broaden participant perspectives of action and change pertaining to health problems in the municipality, by highlighting the power of collective work, showing them the impact that the commitment of health workers and local leaders can have on the health of a community, underlining the power of using existing resources even if they are limited, and helping them identify strategies that they could replicate in their municipality. All of this contributed to improving their motivation and their pessimistic views about the health situation in the municipality, making change feel possible.

The third element was the creation of artistic products, which was identified as an adequate tool to engage with rural populations with low health literacy, because it contributes positively to the social appropriation of knowledge. First, because it facilitates the comprehension and remembrance of health topics, which is consistent with recent studies23,24. In particular, Butala et al25 state that in community health education interventions to control neglected zoonotic diseases, the use of pedagogical tools such as comic books, board games, computer games, and shadow puppet plays, contributed to increasing knowledge about the diseases. Second, these artistic products are an effective tool for the replication of the acquired knowledge, because they can be shared by the participants with their communities. This is also consistent with recent studies; according to Agudelo et al26, the co-creation of pedagogical products such as radio capsules and a card game with representatives of three communities in Colombia, as part of a prevention program on CL, were key to facilitating the replication of knowledge to these communities.

Regarding the results of the program, according to the guide to measure expected results for capacity-building programs proposed by the Aspen Institute3, some significant achievements of the program implemented were the:

- strengthening of the participants’ individual capacities, which will serve them in future projects

- expansion of the community leadership base to work for the collective wellbeing, promoting a shared understanding and vision of the municipality's health problems and the possibilities for transformation

- increase of diverse and inclusive participation in health, by involving participants representing the three ethnic groups of the municipality.

However, to achieve consistent and tangible progress3, it is necessary to continue working on the replication of the capacities developed in the community and in health institutions, which is still incipient; continuing the collaborative and effective work of health institutions and community organizations; and designing and implementing a long-term goal-oriented improvement plan, based on the community's resources.

Despite the advances accomplished with this program, for capacity building to be successful in the long term, it is necessary to achieve constant, sustainable, and measurable progress that allows the use of the developed capacities independently of those who facilitated or promoted their development27.

Still, as established by the National Ministry of Health of Colombia in the protocol for leishmaniasis28, the management of this disease requires informative and educational activities that facilitate the acquisition of knowledge about the disease, its prevention and treatment, and promote the participation of the population in reducing its impact. In accordance with those guidelines, the capacity-building programs implemented promoted the generation of collective and critical knowledge on the health of the municipality, especially about leishmaniasis, which strengthened the community’s capacity for participation and the development of the skills necessary for the participants to become replicators and leaders in health within their communities.

Conclusion

Capacity building in the community is essential to achieve transformations in health. Participatory pedagogical models adequate to the context and its participants allow the implementation of effective training programs that develop capacities within the communities. To achieve a significant impact, it is necessary to ensure the continuity and long-term sustainability of capacity building through replication of knowledge with the cooperation between health institutions and the community. In this way, the capacities developed by the community constitute a valuable social capital for achieving transformations within and outside the health field.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

References

Supplementary material is available on the live site https://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/8201/#supplementary

You might also be interested in:

2005 - Video outreach journal club

Supplementary figure 1: Percentage of knowledge on cutaneous leishmaniasis acquired by students during the workshops.

Supplementary figure 1: Percentage of knowledge on cutaneous leishmaniasis acquired by students during the workshops. Supplementary figure 2: Percentage of disease knowledge acquired by health workers during workshops.

Supplementary figure 2: Percentage of disease knowledge acquired by health workers during workshops.