Introduction

Despite being a small fraction (0.5–2%) of total hospital admissions in Australia, discharge against medical advice (DAMA; also known as discharge at own risk, take own leave or self-discharge), when the patient chooses to discharge themselves before their recommended treatment is complete, is linked with significant human and financial cost1-3. DAMA is distinct from ‘did not wait’, where emergency department (ED) patients are triaged and admitted but decide to leave before seeing a healthcare practitioner4. Patients who DAMA are reported to have more frequent hospital re-admissions1,5 and higher rates of mortality and morbidity than their counterparts3,6. Healthcare costs for DAMA cases are about 56% higher and incur a re-admission cost of around A$8.6 million per year7,8. DAMA patients also challenge the health provider’s duty of care as they endeavour to balance their ethical obligations to protect the patient from harm while respecting the patient’s decision to leave early9,10. Reducing DAMA rates is an important goal in health service improvement.

Factors associated with DAMA are diverse and complex, and include a mix of patient, health service and environmental factors11. The main drivers of DAMA include patient sociodemographics, history of drug and alcohol abuse, mental health issues, healthcare resources constraint and culturally unsafe services9-13. Rates of DAMA are consistently higher for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples (hereafter respectfully referred to as First Nations) compared to non-First Nations patients, who may choose to DAMA due to additional factors such as institutionalised racism, mistrust of health systems, and communication or language barriers14,15. Between 2015 and 2017, 3.0% of all ED presentations by First Nations Australians resulted in DAMA, across all triage categories14. Hospitalisations for First Nations Australians that resulted in DAMA are significantly higher in remote (6.3% of all hospitalisations) and very remote (7.3%) areas compared to those in major cities (3.0%), inner regional (2.3%) or outer regional (3.6%) locations14. During the same time period, age-standardised DAMA rates for First Nations Australians ranged from 3.5 times higher than non-Indigenous Australians in inner regional areas, to 9.1 times higher in very remote areas14. This indicates that there is a pressing need for more research to inform health system change to improve patient outcomes. Geographical barriers to accessing health care increase DAMA rates, and the disparity between First Nations and non-Indigenous Australians is particularly high in remote and very remote areas of Australia16,17.

Despite comprehensive understanding on risk factors for DAMA, there is very limited empirical evidence on the strategies or interventions that are effective in reducing DAMA18,19. Because a DAMA event signifies a potential breakdown in the patient–provider relationship, perspectives of both patients and providers are important to understand current practice and identify opportunities for improvement20. Patients have reported reasons for DAMA to include waiting too long, feeling better, deciding to seek help from an alternative health professional (eg GP), loneliness, family and financial commitments, physical environment of the hospital and poor communication from staff21-23. To our knowledge, reasons for DAMA from the perspective of healthcare providers have only been explored outside of Australia, in large metropolitan hospitals24. Themes described are mostly consistent with the Australian patient experience24 but further research is required in the Australian setting to identify opportunities for service improvement.

The broad aim of this study was to explore healthcare providers’ views on DAMA and identify strategies for preventing and/or better managing DAMA cases. The primary objective was to explore healthcare providers’ experience of managing DAMA cases and their perception of the factors influencing patients’ decision to DAMA. The secondary objective was to gain insight into staff experiences of the current protocols for managing DAMA cases and explore their recommendations for reducing DAMA incidence. For this study, DAMA was defined as patients electing to leave the facility prior to completion of treatment, which is a particular issue for EDs25.

Methods

Study design and setting

This cross-sectional, mixed-methods study was conducted with the clinical staff of a hospital in a remote town with Modified Monash (MM) Model remoteness classification MM 6 (remote community)26 in Queensland, Australia that lies approximately 900 km from the nearest major city. The hospital has an approximate capacity of 70 beds and delivers many tertiary or specialist services. In 2021, the Local Government Area population was more than 18 000 people, with 21.5% of residents identifying as First Nations27. The hospital also treats patients who travel from nearby very remote and discrete Aboriginal communities28. The hospital and health service (HHS), which provides health services to remote and very remote communities located over an area of 300 000 km2, employed a total of 859 staff (all departments) in the 2020–21 period, 7.33% of whom identified as First Nations Australians25. The ED saw approximately 29 000 presentations across all triage categories in the July 2022 to June 2023 period. Data from previous years suggest the region’s health service has a DAMA rate of about 3% overall, with 8.5% for First Nations patients, an increase from the previous reporting period (6.4%)25,29,30. Due to this disproportionate representation in DAMA rates, the HHS has included reducing First Nations DAMA rates as a goal for their Closing the Gap strategies25.

Participant recruitment

All clinical staff (n=21) working at the ED of the remote hospital were invited to participate in a survey and interview regarding DAMA at the hospital. Email invitations described the purpose of the project and the expectation in time commitment should they decide to participate in the study. The inclusion criterion was experience in providing care to at least one DAMA patient in the 12 months prior to the interview.

Data collection

Three experienced clinicians and a health services researcher developed and reviewed the survey and interview guide. The cognitive constructs of the Health Belief Model guided the development of the questions31. This model was selected due to its behavioural concepts regarding why people choose to take action to control or prevent illness, including their perceptions of susceptibility to illness, severity of illness, self-efficacy to take action, and the benefits and barriers of taking action to prevent or seek treatment for an illness or condition31. Interviews explored the perceptions of healthcare providers on the main drivers of patients’ decisions to DAMA and what strategies might be used to facilitate planned discharge with follow-up activities. Informed consent was sought before data collection. Each interview lasted approximately 30 minutes and was audiotaped with the consent of the participants. Participants were also asked to complete a brief questionnaire identifying the reasons they perceive influence patients’ decisions to DAMA and identifying their current practice for managing DAMA cases.

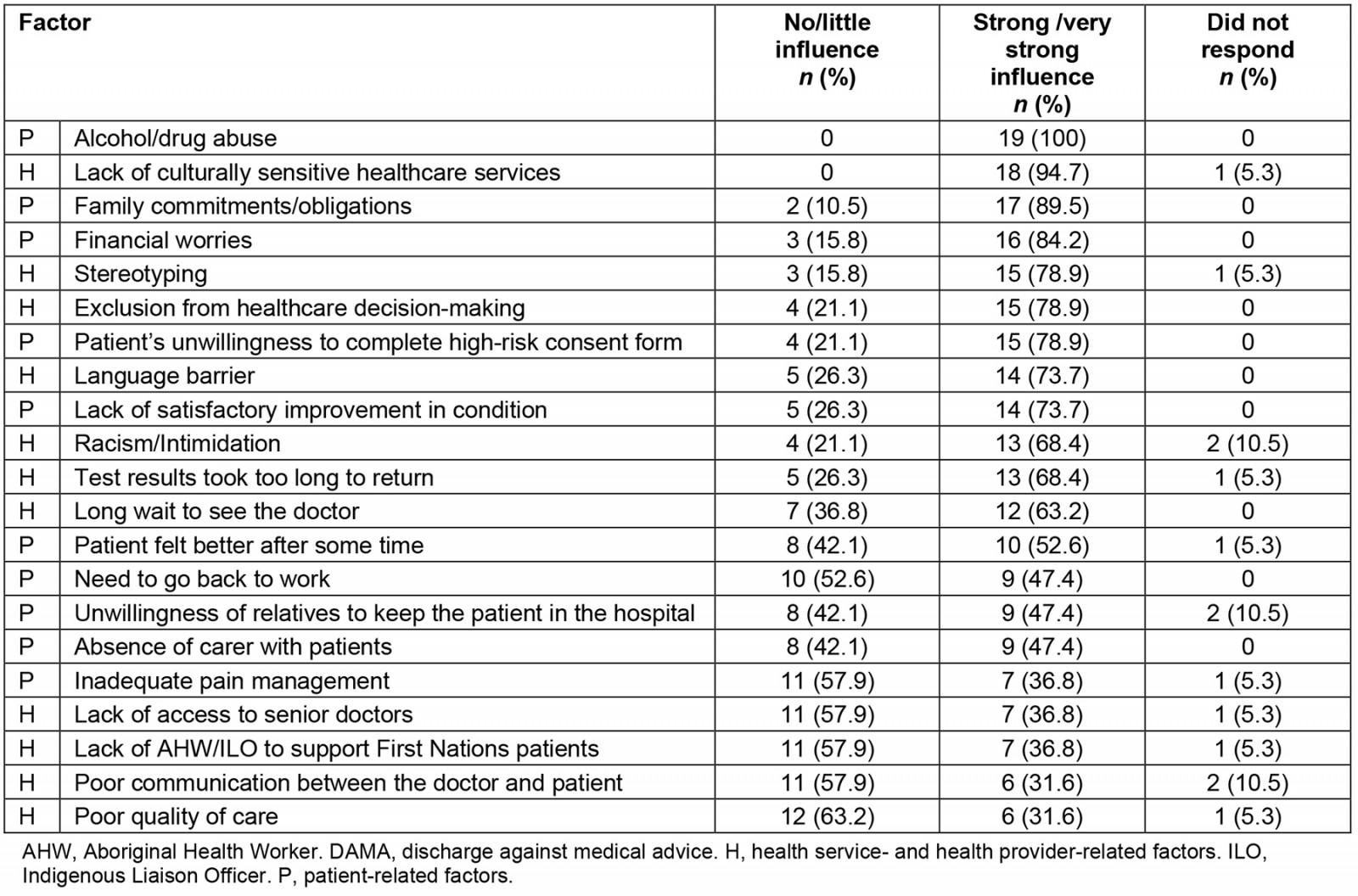

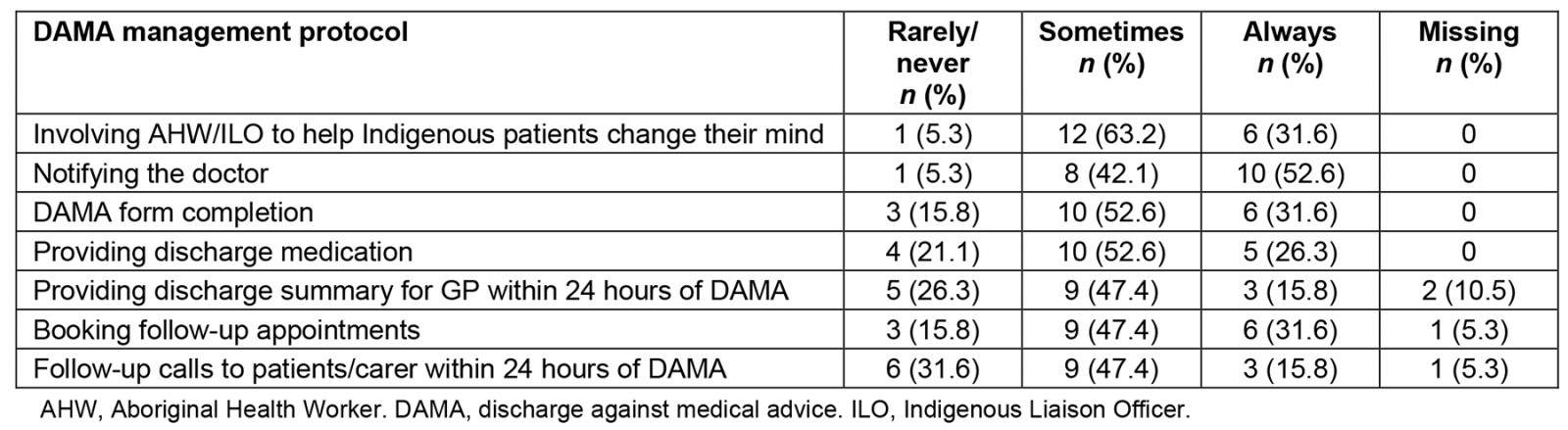

The first part of the survey questionnaire comprised 21 items exploring healthcare providers’ perceptions of factors influencing patients’ decisions to DAMA. The tool included a mix of patient, provider and services-related factors (Table 1). Participants indicated on a four-point scale whether they believed each factor had no, little, strong or very strong influence on a patient’s decision to DAMA. For reporting purposes, results have been grouped into ‘no/little influence’ and ‘strong/very strong influence’. The second part of the survey comprised seven items on the current practice for managing patients who have indicated intent to DAMA. For questions related to DAMA management protocol, responses were provided on a three-point rating scale including ‘rarely/never’, ‘sometimes’ and ‘always.’

Participants who completed the survey were invited to participate in individual, semi-structured interviews. At the start of the interview they were asked to recall a time they were involved in a patient’s care who had discharged against medical advice, how they felt when this patient was planning to discharge or had discharged, why they believed the patient wanted to DAMA, and any recommendations they had to reduce DAMA in their workplace.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the study sample and analyse the Likert scale responses. Qualitative data were analysed by inductive thematic analysis. Each interview recording was transcribed verbatim. Interview transcripts were read and re-read while listening to the audio-recordings to familiarise the researchers with the interview content and confirm the accuracy of transcriptions. Common content between transcripts was coded and grouped into themes independently by CS and AC, which were then further reviewed to ensure coherence. All analyses were compared, and discrepancies were negotiated to create consensus of themes.

Principles of credibility and confirmability were followed to ensure the rigour of the analysis31. Credibility was established by two members of the researcher team (AC and CS) examining the data independently and eliciting themes. Participants’ quotes are provided in the results section to demonstrate confirmability. Reflexivity was achieved, as the researchers undertaking the data analysis had no relationships with the ED staff participants and had not worked in an ED environment, to ensure that participants’ narratives were not influenced by the researchers’ assumptions and were accurately represented in the research findings. The interview findings were compared and integrated with the quantitative data on participants experiences and perceptions regarding DAMA, which supported data triangulation32,33.

Ethics approval

Townsville Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee, Queensland, Australia approved this study (HREC/17/QTHS/114).

Results

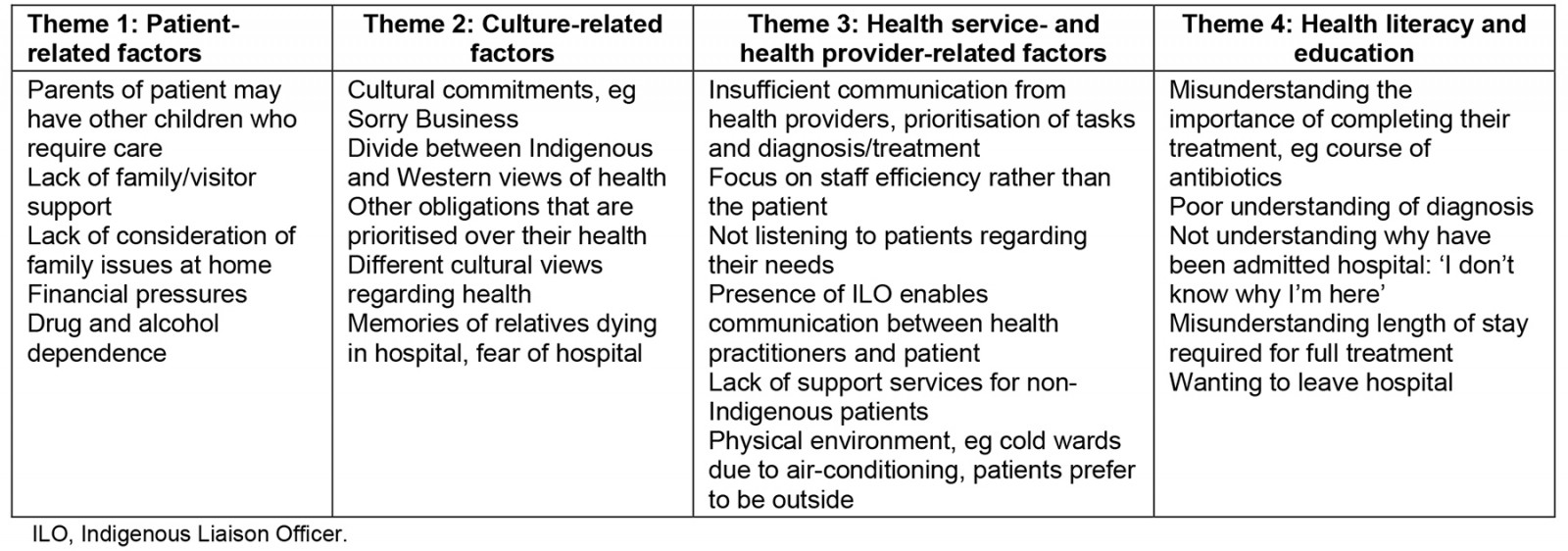

Nineteen of the 21 invited healthcare providers (90.5% response rate) took part in the study. A total of 19 completed the survey and 14 of those participated in an interview. Participants were nurses (n=10), medical doctors (n=4) and five did not provide their professional background. Most participants were female (n=16, 84.2%), aged 30–50 years (n=12, 63.2%) and seven had more than 10 years of working in rural and remote areas. Participant ethnic backgrounds included Caucasian and Asian (both n=6, 31.6%), Aboriginal Australians (not Torres Strait Islander or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander; n=2, 10.5%) and others (n=5, 26.3%). When asked how they felt following a DAMA occurrence, they reported emotions using words such as ‘challenged’, ‘concerned’, ‘confronted’, ‘disappointed’, ‘failure’, ‘frustration’ and ‘understanding’. Survey results are reported in Tables 1 and 2. Perceptions about patient choices to DAMA are in Table 3.

Table 1: Healthcare providers’ (n=19) perception of factors influencing patients’ decision to discharge against medical advice

Table 2: Healthcare providers’ (n=19) current practice for managing patients with impending discharge against medical advice

Table 3: Themes and categories of healthcare providers’ perceptions about people’s choice to discharge against medical advice

Patient-related factors

Three of the four factors most frequently (>80%) perceived by participants in this study to influence patients’ decision to DAMA were patient related: alcohol and drug abuse (n=19, 100%), family commitments or obligations (n=17, 89.5%) and financial worries (n=16, 84.2%). Over half of participants also believed that a patient’s unwillingness to complete a high-risk consent form (n=15, 78.9%) and lack of satisfactory improvement in condition (n=14, 73.7%) influenced a patient’s decision to DAMA. The patient-related factor that was least often perceived to contribute to DAMA was the patient receiving inadequate pain management (n=7, 36.8%).

While 100% of survey participants agreed that alcohol or drug abuse had a strong or very strong influence on DAMA rates, only four interviewees identified this as a reason for patients to leave. Other patient-related factors were family and carer commitments (n=10), loneliness (n=5) and finance (n=3).

During the interview, family or carer commitments were reported by six participants as significantly impacting DAMA levels, while five identified loneliness or a lack of family support as a contributor:

I had a young three- or four-year-old boy who … presented [with] a respiratory tract infection. Mum said she wanted to take him home because she had … another child at home and she didn’t have carers. We advised it’d be better if the boy was able to stay in … she was uncomfortable leaving him behind, and she didn’t have anyone else to stay with him. (Participant 5)

Culture-related factors

Culture-related factors that were most often perceived to influence DAMA occurrences were mostly related to cultural issues and misunderstanding: a lack of culturally sensitive healthcare services (n=18, 94.7%), stereotyping (n=15, 78.9%), language barriers (n=14, 73.7%), and racism and intimidation (n=13, 68.4%). However, a lack of an Aboriginal Health Worker (AHW) or ILO to support First Nations patients was not frequently viewed as an influencing factor (n=7, 36.8%).

These results were supported by the majority of the interviewees (n=12). There was a connecting theme of family and cultural needs not being adequately addressed or recognised within the current system. This arose through the perception that patients DAMA because they have other cultural commitments such as Sorry Business, and there is a conflict between traditional Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ideas about health and wellbeing and treatments versus the Western medical approach.

Aboriginal law was priority for her…the mourning process that they had to go through... But the health system didn't understand that …The biomedical model that we treat them…doesn't fit into the Indigenous ways…the hospital is more focused on medicine and doctors and treating. (Participant 9)

Yeah, they have their own opinion, their own ideas on their health. Maybe they think they stay in their communities, stay with their family is more important. (Participant 12)

Three participants also discussed First Nations patients’ negative experiences and fear of the hospital environment due to associating hospitals with death:

They really don't want to get admitted into hospital. They feel sad, like memories of relatives dying in the hospital … those are most of the reasons why they … DAMA. (Participant 13)

Health service- and health provider-related factors

Health service factors such as exclusion from healthcare decision-making (n=15, 78.9%), and long waits for test results to return or to see the doctor (n=13, 68.4% and n=12, 63.2%, respectively) were selected by more than half of the participants. The health service/health provider-related factors that were least frequently viewed as contributing to DAMA occurrences were poor communication between doctor and patient and poor quality of care (both n=6, 31.6%).

During interviews, communication with patients regarding their care repeatedly arose as a contributor to DAMA frequency:

Staff don’t spend enough time communicating … [the] focus [is] on paperwork and tasks i.e. showering, taking medication, not enough time communicating. (Participant 1)

The important role filled by the ILOs as an intermediary between the health practitioners and First Nations patients was discussed by five participants:

Sometimes we use medical jargon the patient doesn’t understand. … That is when the [ILOs] can be really helpful. (Participant 6)

However, there was also admission that there is no equivalent support for non-Indigenous patients who DAMA:

In ED I know they’ve got … ILOs for Indigenous patients. They don’t have a similar one for the non-Indigenous ones that discharge against medical advice. (Participant 10)

Congruent with survey results regarding exclusion from decision-making, interviewees described the hospital as a disempowering environment for patients:

Every patient has the right to be respected and heard. That sometimes we don’t do that, sometimes that is one big thing that’s missed. (Participant 4)

Health literacy and education

A combination of patient, cultural and health service factors were described by participants as poor health literacy and health education. This was a key reason given by staff as to why they perceive that patients DAMA. This was described by participants as patients not understanding the reason for admittance, their diagnosis, the expected length of time for admission and the need for ongoing treatment. This was articulated by eight participants, all who perceived DAMA often occurs when patients believe their condition has improved and they do not understand the importance of remaining in hospital to complete their treatment. This seemed to be a particular issue with antibiotic use, with several staff members reporting patients DAMA without completing the required course of medication:

Once they start feeling better … they think they should be discharged from the hospital … sometimes they don’t complete the course of antibiotics. (Participant 8)

She wanted to go. She hadn't even had six hours of antibiotics, so she had no concept of the importance of what she needed to do to stay here. (Participant 3)

Participants described how patients sometimes don’t understand why they have been admitted to hospital, and how poor health literacy leads to misunderstandings about how long they are staying or what their treatment is:

Sometimes they would say I don’t want to be here. I don’t even know why I’m here. (Participant 13)

Survey items that may have indicated poor patient health literacy and education included exclusion from healthcare decision-making and patient’s unwillingness to complete a high-risk consent form (n=15, 78.9%), lack of satisfactory improvement in condition (n=14, 73.7%), and test results taking too long to return (n=13, 68.4%).

Current DAMA practices

With the exception of ‘notifying the doctor’, all DAMA management practices were most frequently reported by participants to only be actioned ‘sometimes’ rather than ‘always’ (Table 2).

Current DAMA procedures and recommendations

Participants also described their department’s current procedures for management of DAMA patients, strategies they utilised to attempt to divert or reduce harm of impending DAMA patients, procedures undertaken following a DAMA case, and their recommendations to reduce DAMA rates.

Managing DAMA patients

While three participants did acknowledge that they were aware a DAMA policy existed, they were unsure of the procedures relating to DAMA. Four participants knew where the DAMA policy was located and were able to provide some description of the policy. Some participants acknowledged the policy had recently been updated, but some staff were still continuing to use the old policy. Patients leaving without notifying anyone or without staff noticing was identified as a major concern.

Strategies used with impending DAMA

Activities when staff have recognised an impending DAMA were described: communication with patient, communication with patients’ significant others, assessing capacity of patient or parent to make the decision to DAMA, and practical tasks to reduce harm of DAMA.

Communication with the patient included the treating doctor, nurse, social worker or DAMA nurse discussing treatment needs and risks/benefits of hospitalisation with the patient (n=9); and ILOs or AHWs speaking with the patients about their healthcare needs (n=7). Talking with family or friends to influence the patient to stay was also identified by a few participants. Assessing the capacity of the patient or parent to make the decision to DAMA and consider involuntary admission if the patient was at imminent risk to self or others was identified to reduce potential harm associated with DAMA. If those strategies did not work, a small number of staff identified practical steps to reduce the harm of a DAMA: removing any treatment equipment such as intravenous drips, preparing discharge or takeaway medication, completing the DAMA form and organising follow-up contact or appointments, despite concerns for the patient’s wellbeing. One participant disagreed with these cases being converted to a planned discharge rather than a DAMA:

Patients who are planning to discharge, it's not the ideal choice, but the team will do what they can to make it so that the patient can discharge safely … they will be given things like antibiotics, an explanation of how to take them when they go home … organise for follow-up appointments, whether it's outreach appointment or here in town. But it's not a planned discharge when we do that and I disagree when people say it is a planned discharge. (Participant 10)

One participant stressed the importance of the role of the ILO, describing this role as a mediator between the professionals and the cultural needs of the patient. The reality of the availability of the DAMA nurse and ILO roles was described by seven participants. Issues included staff only available during ‘office hours’, no backfill when staff are on leave, not enough ILOs to cover all wards and ED, and the DAMA nurse position being vacant for extended periods of time.

Procedure after DAMA

Procedures following a DAMA event included contacting the nurse-in-charge of the shift; contacting police or security to look for patients or to do a welfare check, a follow-up phone call to the patient to encourage readmission, liaising with community health and primary care clinics for follow up, and documenting the DAMA and any attempts to prevent or reduce harm of DAMA.

Recommendations to prevent DAMA

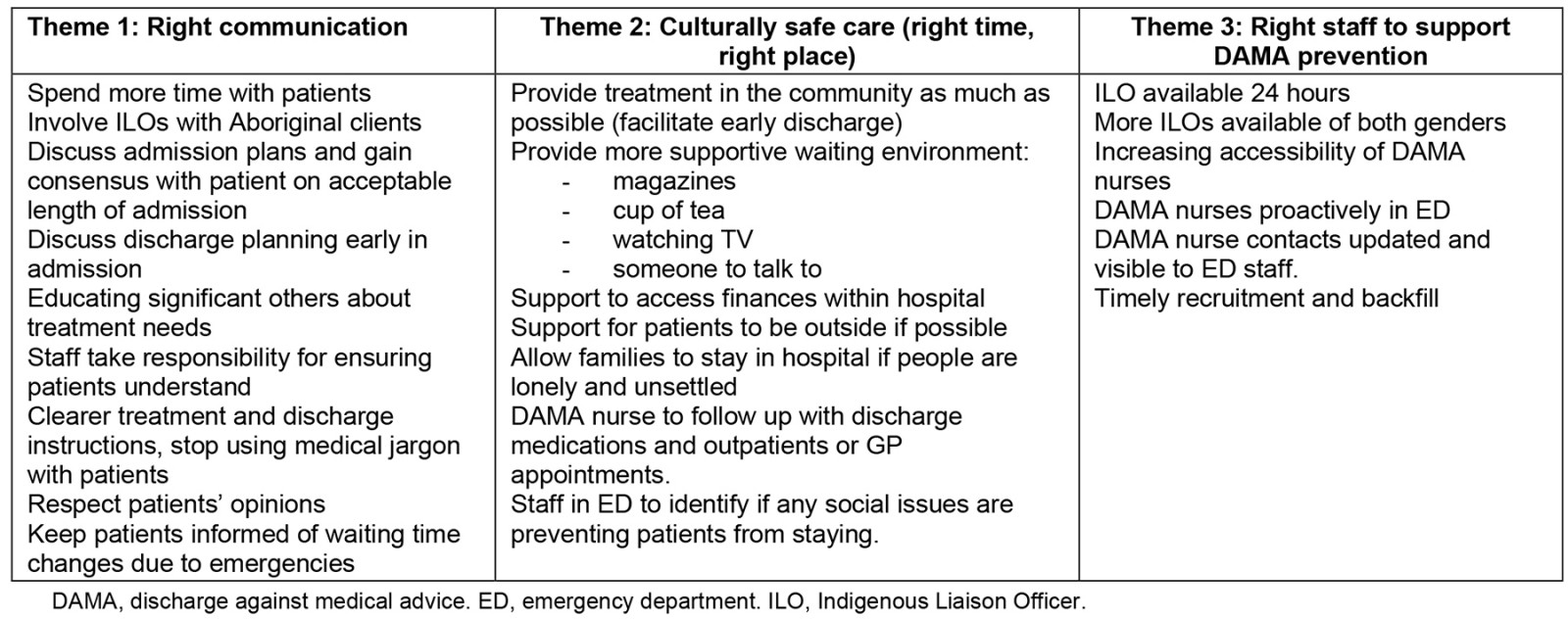

Participant recommendations were categorised and grouped into three prominent but interrelated themes: right communication, culturally safe care (right time, right place) and right staff to support DAMA prevention (Table 4).

Participants discussed improving the communication between the patient, patient’s family and the treatment team (n=6), and improved patient education or treatment awareness (n=8). This theme was named ‘right communication’ as it encompassed not only how positive communication could be achieved (involvement of ILO staff, treating team responsible for checking patient understanding, maintaining respect for patients’ opinions), but what else is required, such as giving clearer and simpler instructions and gaining consensus with patients on length of admission:

… sometimes we use medical jargon the patient doesn't understand … that's where the [ILOs] can become really helpful … Community nurses as well … Does this patient need to be in a hospital or can we put in services to [treat] them outside the hospital … So discharge planning plays a role in that as well. (Participant 6)

Within this theme, participants also suggested that staff at the start of the hospital admission process (ED) should identify if any social issues are likely to prevent patients from staying in hospital as it will enable staff to understand patients’ needs. Consequently, this may allow for patients, families and staff to work together to develop a plan to support admission, as one participant indicated that home and family issues are not always considered while patients are in hospital.

Interrelated with providing the right communication to patients and their families was the second theme: culturally safe care (right time, right place). The statements identified within this theme can be grouped into two categories. First, the hospital environment and improving how the patient experiences their time within the hospital, including having access to distraction activities when waiting long periods of time (TV, visitors, magazines), more support for families to stay at the hospital if needed, and allowing patients to be outside if desired. The second category related to the interaction between the hospital and community health providers. Participants suggested patients could be discharged earlier and treatments continued within the community so patients can attend to their family or cultural responsibilities.

Sometimes we try and keep them in hospital for a lot longer than they need. Where a lot of their treatment could be done as either an outpatient or have follow-up appointments as outpatients, instead of keeping them in hospital. (Participant 4)

The third recommendation theme was the need for the right staff to support DAMA prevention. This was predominantly focused on the provision of more ILO staff and the provision of a DAMA nurse. Both positions were reported by most participants as being important for reducing DAMA events.

Employ a DAMA nurse … it was really helpful when she was there. A lot of patients stopped leaving the hospital. She would intervene and talk to them and plan … put a Plan B. (Participant 11)

Table 4: Themes and categories of healthcare providers’ recommendations for preventing discharge against medical advice

Discussion

The experiences of a patient who decides to DAMA may be challenging and confronting for many health professionals. Managing these experiences in the busy hospital environment, where the flow of patients is constant, can leave little time for staff to reflect on the impact this has on them, the team and the overall culture of the healthcare environment31. DAMA presents a deviation from the health providers’ expected treatment plan and presents a significant challenge to the patient–provider relationship20. Strategies to tackle the rates of DAMA must transcend the medical authority framework, which inherently requires the patient to be compliant and follow the provider’s advice they sought, and the provider to competently maintain a therapeutic relationship despite disagreements while supporting the patient’s personhood20. The factors identified by participants in the current study align with concepts of the Health Belief Model, regarding why people choose whether or not to take action regarding their own health, such as their perceptions of severity of illness due to poor health literacy, or barriers to taking action including drug and alcohol-related issues or a lack of family support31. Despite preconceived notions that people who do DAMA do not prioritise their health, evidence suggests that they are in fact profoundly invested in their health and wellbeing23. In contexts with high populations of First Nations people, such as the setting of this study, that concept of health is holistic, including the physical, emotional, cultural and spiritual wellbeing of both the individual and community34. The patient makes decisions to adhere to medical advice based on every aspect of their life – their responsibilities, commitments, comfort, safety and medical needs23. It is the combination of unmet needs that may outweigh the benefit of staying in hospital to complete treatment23.

Respondents in this study identified that patients choose to DAMA for a range of reasons, from personal reasons, family and cultural obligations, to many issues related to indigeneity and culture. All participants agreed that alcohol and other drugs can influence a patient’s decision to DAMA, a finding that is consistent with the literature. A study by Katzenellenbogen et al found that alcohol admission history was a strong predictor of DAMA16, while Einsiedel et al found that a history of alcohol use and a desire to drink alcohol were associated with higher rates of DAMA21. Patients who are admitted with drug- or alcohol-induced psychosis are also more likely to DAMA35. Alcohol and drug addiction can contribute to DAMA due to withdrawals, alcohol dependency and leaving to obtain alcohol7,35,36. First Nations Australians face stigma, stereotyping and racism related to drug and alcohol, and health providers’ actions during admission are a key determinant for DAMA35. A study by Askew et al describes a First Nations patient’s experiences of being labelled an alcoholic and ‘treated with disdain’23, which contributed to his decision to DAMA, while another had been labelled as a self-discharge when he went outside the hospital to smoke. Consideration of the individual patient’s needs, and appropriate communication, assessment and treatment, including alcohol addiction needs, are vital to reduce DAMA and improve hospital experiences35.

It is significant to note that a lack of culturally sensitive healthcare services, stereotyping, language barriers, and racism or intimidation were all perceived to influence DAMA cases by the health providers who participated in this study. However, the majority of respondents believed that poor communication between doctor and patient, and poor quality of care, had little to no influence on patients’ decision to DAMA. This suggests that participants considered quality to refer to the medical and procedural service, separate from the provision of culturally safe care. This separation between the service and the ‘product’ of health care potentially allows professionals who are administering the medical care (the ‘product’) to diminish their responsibility in ensuring the service that is provided is culturally safe and appropriate37. It is potentially a reflection of a health system that defines biomedical knowledge as superior and disregards a holistic approach to health and wellbeing38. This may indicate poor awareness of the influence of stress caused by racism on patients’ adherence, trust and decision-making39. Other studies exploring patient experiences of DAMA confirm the results of this study, that patients’ cultural considerations are not being met40,41.

Providing a healthcare environment that makes one feel safe in which one’s culture, identity and beliefs are respected and given consideration is enshrined in the Australian Charter of Healthcare Rights42. Australia is not unique in finding its health care grappling with how to improve cultural safety. American emergency medicine organisations have called out systemic racism in health care as a ‘public health crisis’, demanding change from individual health professionals and policy developers36. A report published by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare into cultural safety described up to 32% of First Nations Australians reported they went without the care they needed due to cultural reasons including language barriers, discrimination and a perceived lack of cultural safety, which may be supported by the results of this study43. DAMA rates are a key performance indicator for all public hospitals and are related to one of the key strategies in Closing the Gap of health inequities between First Nations and non-Indigenous Australians40. An increase in ILO and Indigenous health professionals has been identified as a national priority alongside educating the health workforce more broadly to provide culturally safe care36,44. DAMA nurses and ILOs are valuable inclusions in the healthcare team, improving communication between healthcare professionals, patients and family, and reducing DAMA rates21,45. Participants perceived these roles to be effective; however, they also reported recruitment and retention issues such as the DAMA nurse position having been vacant for approximately a year. All but one participant thought a lack of culturally appropriate or safe care was a factor influencing DAMA. This study has highlighted the need to improve the safety of health services for all Australians. The socioecological model for anti-racism in emergency medicine encompasses a holistic model, providing recommendations from the individual health professionals through to policy changes36. This model may provide some structure for EDs looking to reduce the impact of racism on patient care; however, change requires ongoing investment in workforce training and professional development. Cultural safety requires the health provider to understand their own culture and recognise the inherent power imbalance presented by dominant, Western systems: it is everyone’s responsibility and should not solely rely on the availability of ILOs and AHWs37.

Health workforce shortages are common in rural and remote Australia, and this impacts on the capacity of health services to provide adequate, culturally safe care46. Early identification of potential DAMA and consideration of a more appropriate care environment such as earlier discharge with treatments continued within the community setting was recommended by participants. The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the importance of improving community health services to reduce the need for hospitalisations, and significant investment has been made in implementing new ways of providing care47. These initiatives, including improved access to telehealth and rapid discharge to home care services, including hospital in the home, may prove effective in reducing DAMA47.

Limitations

This study is limited by the inclusion of ED staff only at a remote community hospital and may not be generalisable across other departments or hospitals in Australia, due to other contributing or potentially contributing factors. Although it provides valuable insights that may be applicable across rural Australia, perspectives of health professionals in other hospitals may differ. The results of this study are based on participant opinions and beliefs and is not able to determine causality of DAMA. Some participants also chose not to answer certain questions, and while all respondents were working in the ED at the time of data collection, they may have recalled experiences working in other departments. This study does not consider the patient or family perspective.

In the context of remote Queensland where Aboriginal Australians are disproportionately represented in DAMA cases, the patient’s voice must be considered. DAMA research in Alice Springs (a remote hospital in Northern Territory, Australia) has provided some insight into this voice21. The Alice Springs study supports the conclusions drawn from this study, that DAMA in the remote Australian context is often linked to a lack of culturally safe hospital environment, along with personal factors such as alcohol dependence and family commitments. Improvements can be made by the involvement of ILOs, who are often part of the patient’s community21. Lastly, the data in this study were collected between 2016 and 2017. Since that time, health system improvements have been made – including an increase in funding, which has seen more ILOs on board with increased access hours up to 11.30 pm alongside multipurpose cultural safe places25.

Conclusion

In this study, emergency department staff in a remote Australian hospital identified patient, cultural and system factors that they perceive influence a patient’s decision to DAMA. ILOs, AHWs and DAMA nurses were all identified as important roles to bridge the cultural and communication barriers for First Nations Australians who are disproportionately represented among DAMA patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Dr Cho Cho Mar, Dr Niraja Rajeevan and Dr Lauren Vernon for their early support. We would also like to acknowledge North West Hospital and Health Service for their support of this project.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.