Introduction

The current COVID-19 pandemic has emerged as one of the greatest challenges to societies and to global health systems and science in the past 100 years, making it imperative to restructure health networks and systems1. Fast and articulated responses are crucial to face these challenges, among them the definition of the role and responsibility of primary health care (PHC)2.

The scientific community responded very quickly to this exceptional health emergency and important articles were published focusing on the role of PHC3,4. However, the particularity of the rural context regarding the role of PHC in the pandemic was scarcely studied in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic5. It is worth recalling that in rural areas a strong PHC is even more important, as it is able to reduce health inequities between urban and rural territories6.

The definition of rural and urban spaces includes some elements that are important for the creation of planning and management actions of the territories, even though they capture only part of the reality. These elements are based on political-administrative criteria, population size, population density, morphological territory patterns, economic activities and a population’s way of life7.

Rural communities have differentiated health risks that add to the growing needs of their populations. They suffer chronically from socioeconomic disadvantages; difficulties in mobility, transport and access to health services; in addition to linguistic and cultural barriers. Added to these factors are the insufficient infrastructure of health services, the limitation of clinical equipment and the difficulty regarding the retention of health professionals in these regions5.

In 2009, the OECD added the criterion of accessibility to the typology of population density, with the influence of distance from the rural area to the urban center. This criterion is translated, then, by the displacement time between non-urban areas and urban centers, delineating areas close to cities or remote areas8.

In this work, we propose to conceptualize PHC in the light of Vuori9, especially under four different forms of understanding: a set of activities, a level of care, a strategy for organizing health services and a guiding philosophy of actions in a health system.

In the international literature, PHC is guided by structuring axes, considered by their essential and derived attributes, which consist of first contact, longitudinality, integrality and coordination of care, family and community orientation, and cultural competence, respectively. In this sense, in addition to being a strategy for organizing health systems and services, PHC is based on a model for changing clinical and care practice10. In this way, PHC is ideally composed of multidisciplinary teams supported by integrated reference systems so that priority is given to the most vulnerable, and health inequalities are reduced – maximizing community and individual autonomy, participation, and control, and involving intersectionality11.

Furthermore, we understand PHC as a combination of primary care and public health functions in order to provide integrated care; a means to empower people and communities, and intersectoral actions12.

At the interface of PHC and rural and remote locations, an important international integrative review carried out by Franco et al defined three basic categories to outline the most relevant strategies: access to health services, health organization and the health workforce13. Access was related to geographic aspects, users' displacement needs and access to hospital and specialized services, the healthcare organization (including structure and resources), operation of health services, and community-based management. Regarding the health workforce, the following stood out: professional profile and role, and attraction/retention factors. The authors highlighted the cross-cutting actions in relation to these three assessed dimensions: community work, extension and visitation models, information and communication technologies, access to assistance and professional training and development, equitably distributed according to population health needs11,13,14.

In line with the different individual and collective approaches, a quick and comprehensive review of the main international protocols highlighted the main dimensions outlined in PHC when facing the COVID-19 pandemic: public health, focused on epidemiological surveillance and care flows; the clinical dimension (continuity of care via telehealth); the organizational dimension; and the systemic dimension15.

A vast literature on the COVID-19 pandemic and its clinical and epidemiological management has been published since the start of the pandemic in 2020. Less frequent, however, is the approach of literature in the pandemic in the PHC context. Even less is known about the complex relationship between the ways of coping with the pandemic in remote locations, while having PHC as the main reference. Thus, the objective of this scoping review was to analyze the set of initiatives and innovations, both individual and collective, that were developed to face the COVID-19 pandemic within the scope of PHC, in rural and remote areas, during the first 18 months of the pandemic.

Methods

The methodology used for the present study was a scoping review16 aiming to carry out a literature mapping based on several study designs of the main concepts of the field of interest.

The scoping review allows evaluation of different types of studies, although it does not provide definitive evidence-based answers, being especially useful when the subject is complex and urgent, and when there are considerable gaps, even in the presence of emerging and hectic evidence, as is the present case. Thus, it allows the definition of key concepts and sources of evidence that can inform practices, policy formulation and research. In this process, it is essential to guarantee methodological rigor and transparency; the possibility of critical evaluation of the set and synthesis of the results, even without individualized and formal evaluation of the quality of the studies; and the balance between breadth and depth17.

In 2005, Arksey & O'Malley published the first methodological framework for conducting scoping reviews, as a six-step iterative process: (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) charting the data; (5) collating, summarizing and reporting the results; and (6) optional consultation16. Subsequently, Levac et al improved these steps, including the relationship between the research objective and question, balancing the feasibility of the study with the necessary scope, carrying out the selection in groups in an iterative way, including quantitative summaries and thematic analyses, identifying the implications of the studies for practice and policies, and making consultation mandatory18. More recently, Peters et al added the need to align the research objectives and questions to the inclusion criteria; the planning of the stages of identification, selection, extraction and presentation of evidence; the performance of a synthesis of the results, relating it to the objectives; and the formulation of conclusions and their practical implications19.

Based on the objective outlined in this study, the following research question is proposed: ‘What individual and collective initiatives and innovations were developed within the scope of PHC to face the COVID-19 pandemic, in rural and remote areas?’ We also sought to answer two derived questions: ‘What are the necessary organizational and intersectoral initiatives?’ and ‘What are their challenges?’

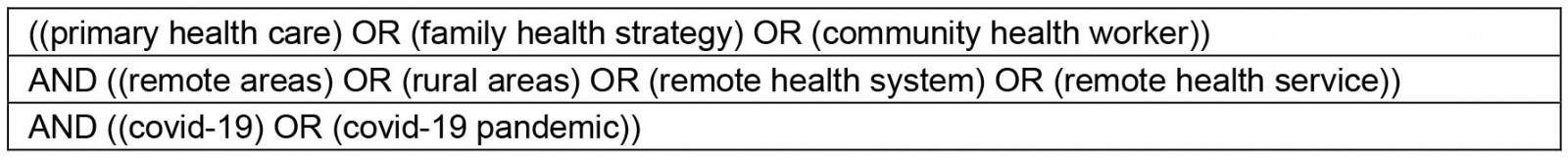

Search words (Table 1) were identified based on a decision made by the researchers, aiming to allow the screening of the titles and abstracts of studies that encompassed the population, the concept and the context20 guiding the review question. The population included traditional peoples, primary care users and communities attached to the territory. The concept was related to organizational, individual and collective initiatives to face the pandemic and the selected context was both clinical (PHC) and spatial (remote/rural locations).

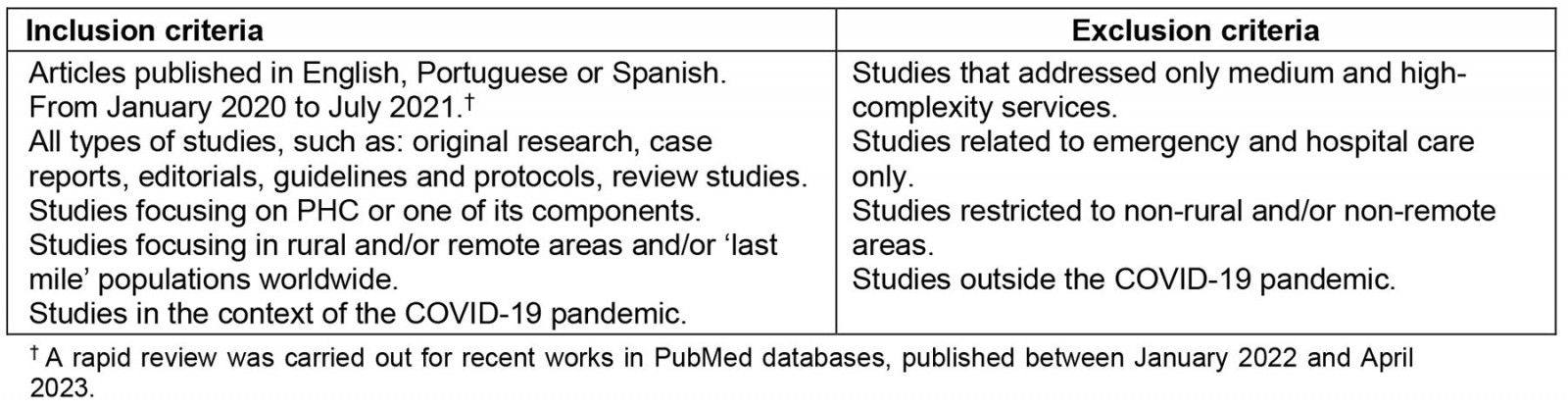

The literature search was limited to publications in English, Portuguese and Spanish, initially limiting them to studies published between January 2020 and July 2021, complemented by a rapid review, including other relevant articles published between January 2022 and April 2023. The focus sought in the literature comprised the initiatives and innovations carried out within the scope of PHC in rural locations during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as comparisons with pre-pandemic situations and between different countries.

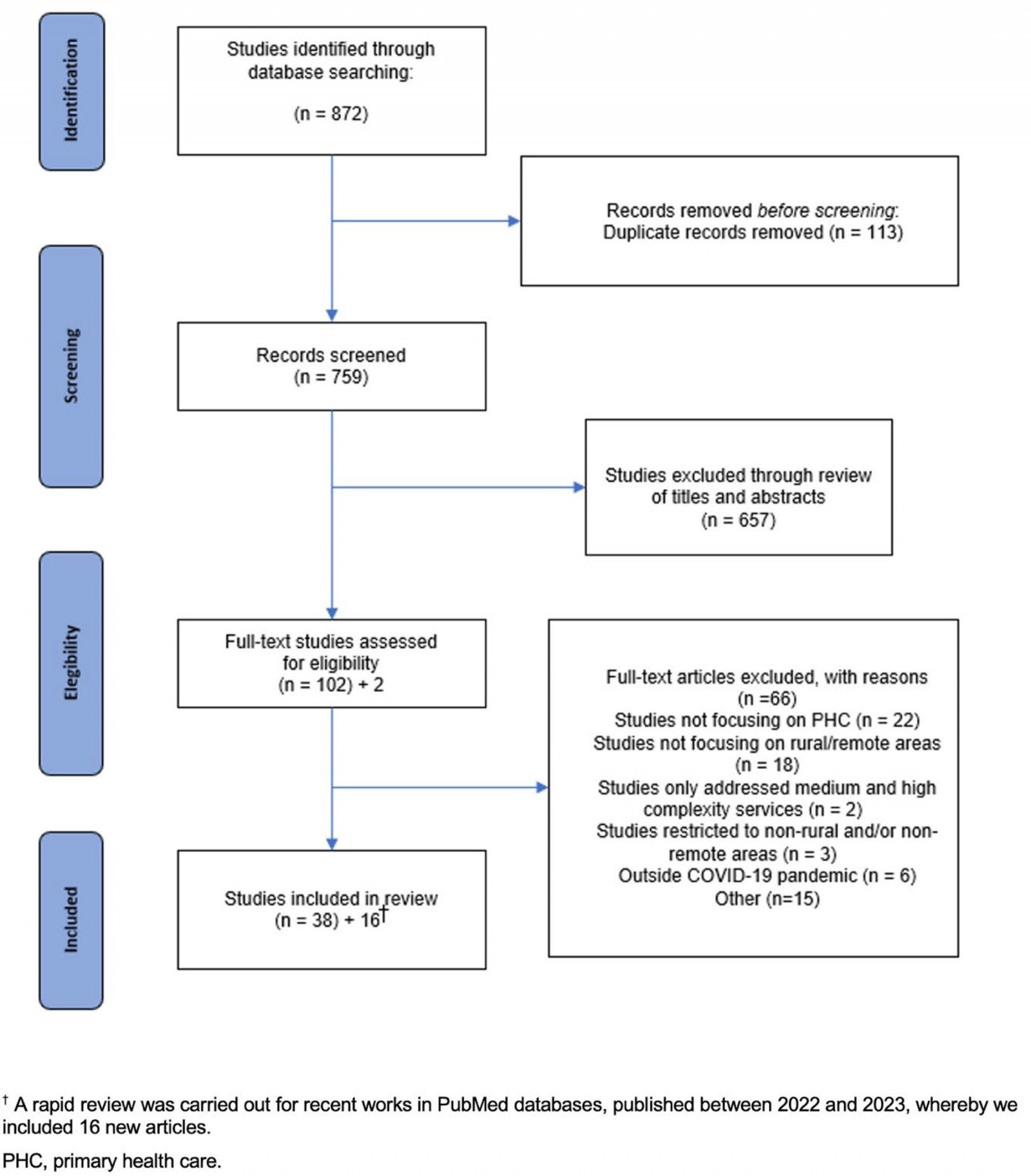

The literature search was carried out in the PubMed and DOAJ, Gale, Onefile, Web of Science, Wiley, Proquest and SAGE databases. The bibliographic information of each search result was imported into Rayyan (Intelligent Systematic Review; https://www.rayyan.ai). Subsequently, articles in duplicate were removed and the abstracts were reviewed. The flowchart in Figure 1 depicts all the steps taken from the identification of the studies and their quantitative data. Selection, eligibility and inclusion steps are detailed below.

Titles and abstracts were independently evaluated (blinding) by two researchers, leading to the exclusion of studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria or that included any of the exclusion criteria defined by the researchers, as shown in Table 2. To resolve disagreements between the two researchers in this initial evaluation (only nine articles), a third researcher who had not participated in the first phase provided her opinion, which allowed reaching a final decision on the inclusion of the initial studies. The articles were classified according to the inclusion and exclusion categories, in addition to an intermediate category (‘maybe’), so that they could be reassessed with greater precision and later defined through agreement among the researchers.

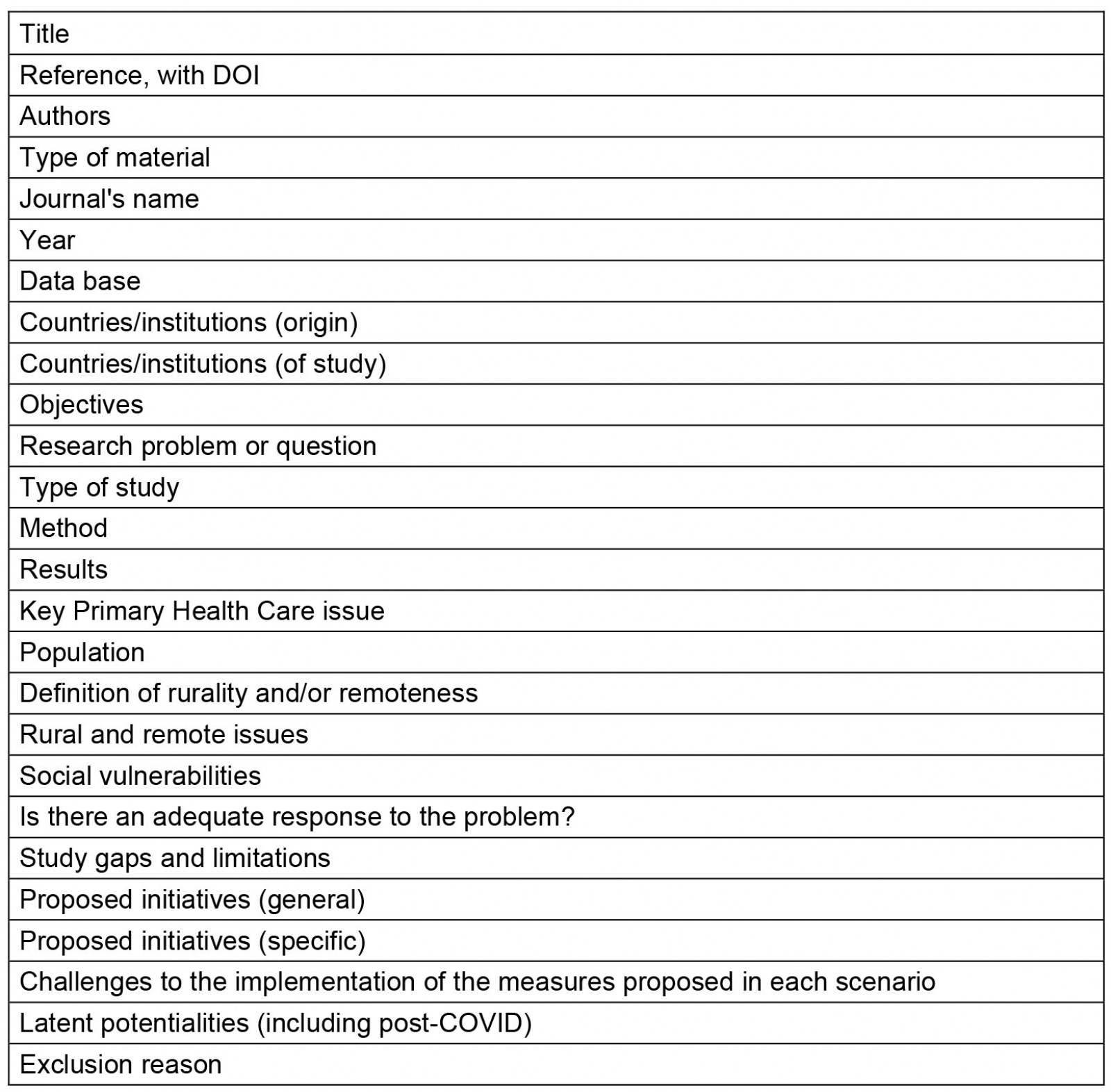

After this, the studies included in the first phase were read in full by two researchers, who independently reviewed them. The reading in full allowed the charting and summarizing of these articles in a data extraction instrument, built after testing some elements of analysis, which resulted in an analytical extraction table that allowed categorizing the items according to the content that answered the research question. The elements in this table (Appendix I) were independently analyzed by the researchers, defining which studies would be included or excluded, after their full reading and synthesis.

We also checked for updates: a rapid review was carried out by two researchers for recent works in PubMed databases, published between 2022 and 2023. Thus we added 16 new articles, out of 44, which were also considered and will be thoroughly discussed along with the other results.

The articles were classified not only by country of study and origin of the first author, but also as sensitive or specific, according to their scope and comprehensiveness in relation to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Thus, although a relevant set of studies did not fully meet the inclusion criteria, their reading was maintained to support the discussion, since they had important intersections between pairs of the PHC, rural and remote, and COVID-19 triad.

Based on the theoretical framework used in the review, the third researcher, once again, participated in the decision on the discordant articles, which allowed proceeding to the discussion of the review.

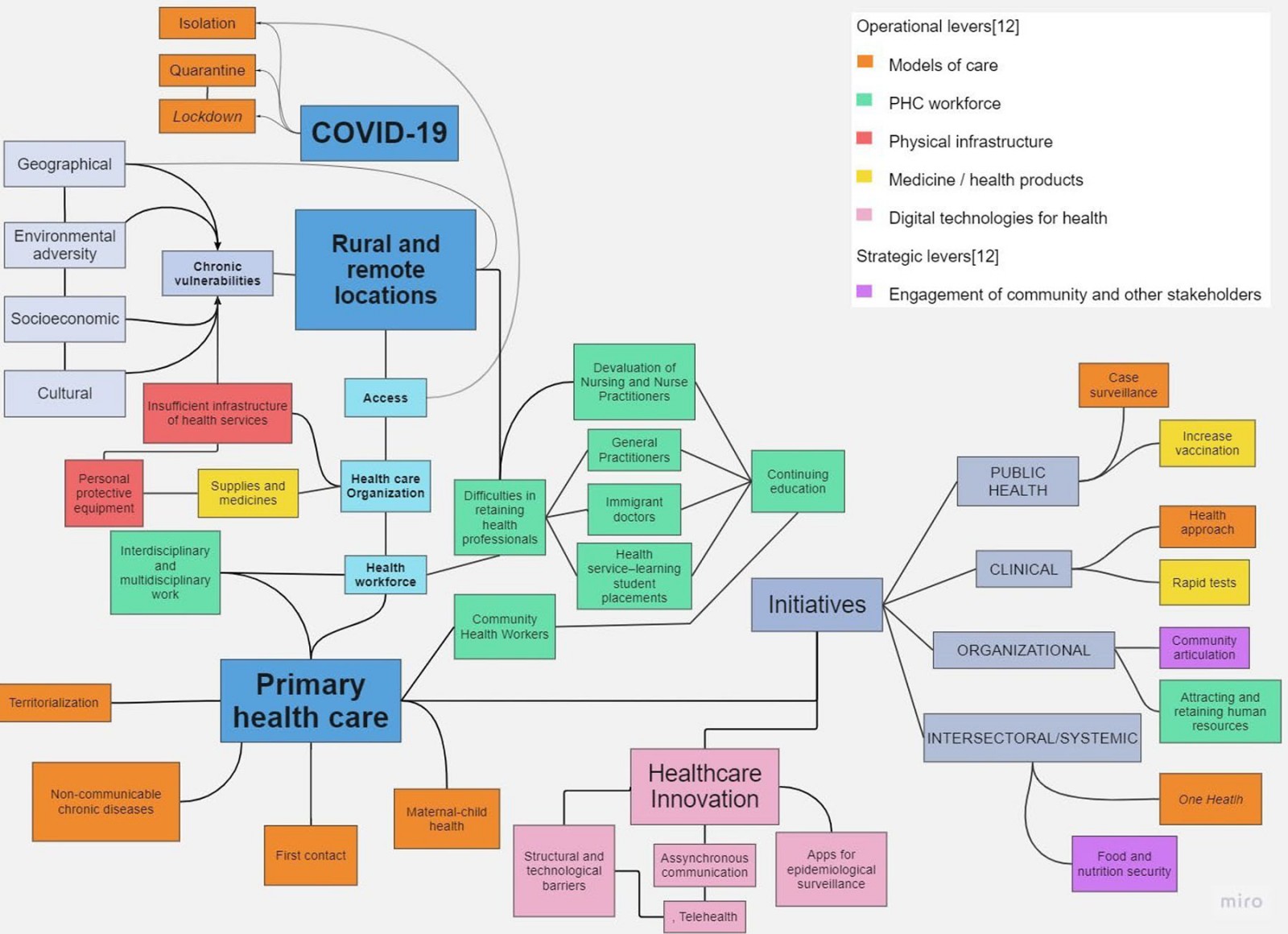

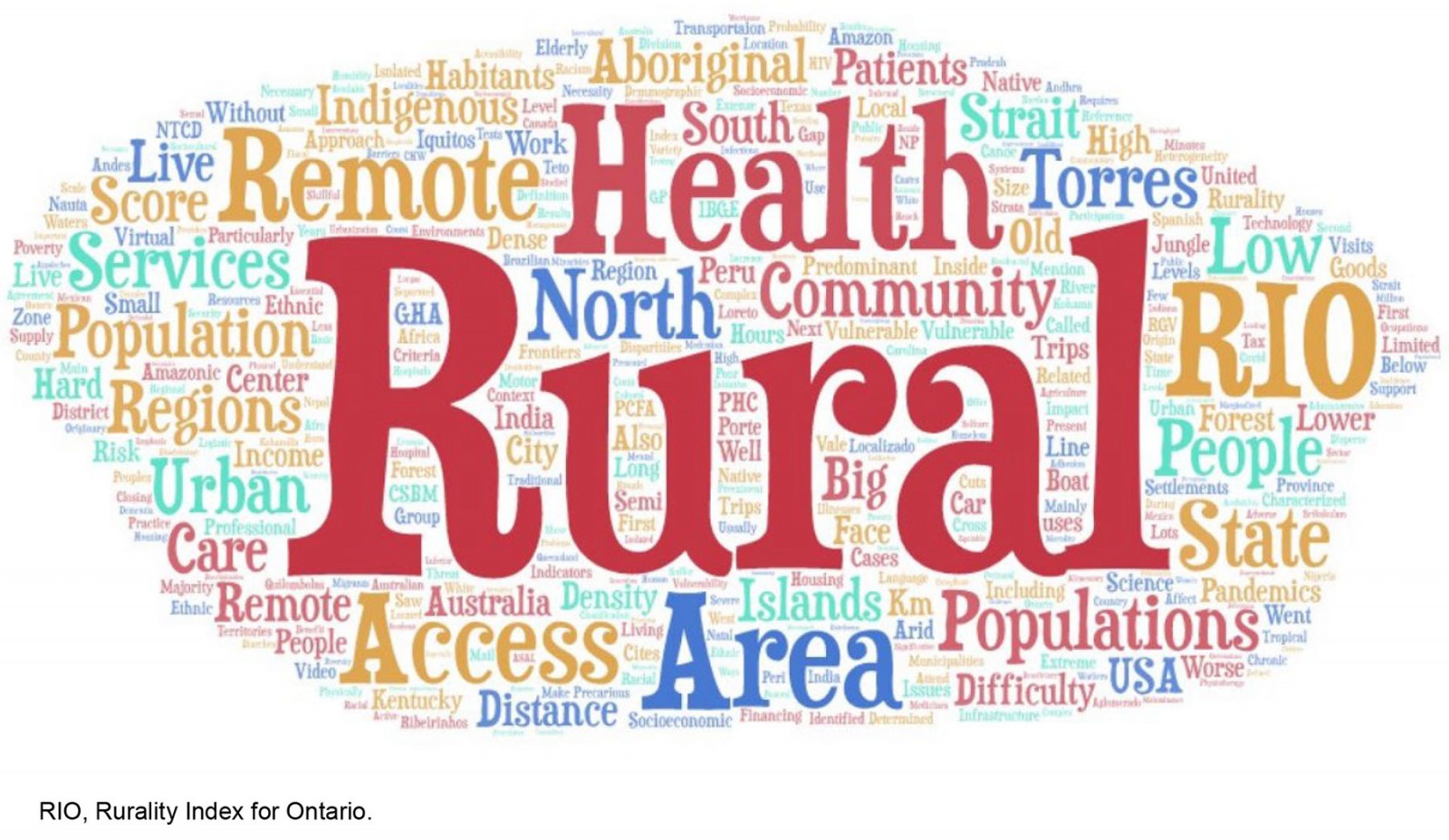

An important part of this analysis can be seen in the word clouds relating the answers of the articles to the research questions and their relationship with PHC and rural and remote locations. From these intersections, the word clouds were constructed, using the same language, aiming to visualize the frequency and relevance of the identified terms, in an open categorical way, as a representation of a hierarchical list of the selected extracts. Thus, the more frequently the term was identified, the larger its size, allowing a quick visualization of its magnitude and relevance in the qualitative analysis. Based on core PHC operational and strategic levers12, a cognitive map was also included, aiming to offer a synthesis of the observed and analyzed concepts (Appendix II).

Table 1: Keywords for electronic database search

Table 2: Review inclusion and exclusion criteria

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram for scoping review process.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram for scoping review process.

Ethics approval

This work was a literature review and relied on secondary materials; thus, it did not require ethics review.

Results

The main initiatives in PHC were related to healthcare access, but also to the coordination of care, comprehensiveness and longitudinality. Regarding innovations, telecare and customized communication stand out, as well as the role of community health workers and health surveillance, and the importance of retaining professionals and valuing human resources in health. Cultural, equity and vulnerability issues occupy an important space among the initiatives (Fig2).

Most articles included originated in Australia, Canada, the US and India. In Africa, articles from Nigeria, South Africa and the Greater Horn of Africa (Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda) stood out. In Latin America, Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador and Peru stand out. In Europe, Spain, Denmark and the UK were also present.

An interesting point is that the description of rurality and remoteness is practically superimposed with that of the specific populations, present in geographic areas of difficult sociospatial and cultural access (Fig3). Very few studies indicate an index to measure rurality – presenting, at best, vague descriptions of rurality and remoteness, which are illustrated in the distances and obstacles to overcome.

Most of the publications analyzed are research articles, but editorials, letters to the editor, short reports, comments, special communications and guidelines were also included, provided they contained the relevant information to answer the research question. In particular, attention is drawn to the continuing education guideline for telecare, a publication of the Spanish Society of Primary Care Physicians21. This guideline offers a step-by-step guide for carrying out remote consultations, differentiating teleconsultation from video consultation, and providing instructions from consultation planning and opening, to the information necessary for clinical management, as well as communication with the patient and instructions in case of clinical worsening or need for validation with a face-to-face consultation21.

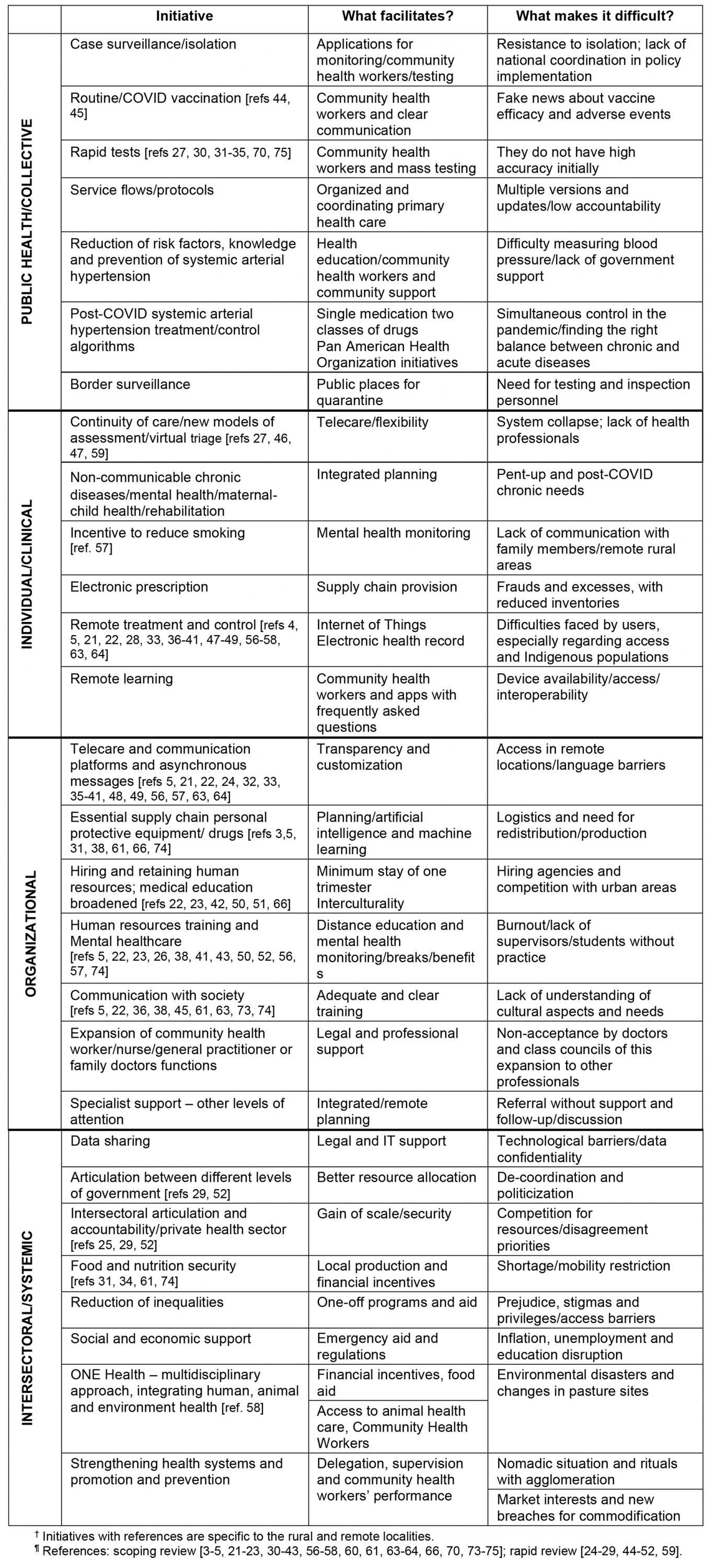

The main initiatives identified, classified by dimension, along with the factors that facilitate or limit its implementation, are listed in Table 3. It is noteworthy that the initiatives specific to rural and remote locations are predominantly of an organizational nature, while there is a scarcity of initiatives in the other dimensions, mainly in the collective action one. Another important aspect is that access to and the quality of health care were present in all dimensions. Moreover, the issue of retaining professionals and attracting the health workforce deserves to be highlighted in the organizational dimension22,23.

We found new evidence that shed light on the set of initiatives, most of them also in the organizational dimension, such as asynchronous forms of communication24, medical education25, human resources training and mental health support26. In the clinical field, the most recently published studies also address initiatives on new models of assessment and virtual screening27, in addition to the provision of remote antiviral treatment28. In the systemic dimension, the most recent evidence regards the articulation of intersectoral workgroups29.

Table 3: Top-ranked initiatives and their facilitating and limiting factors3-5,21-65†¶

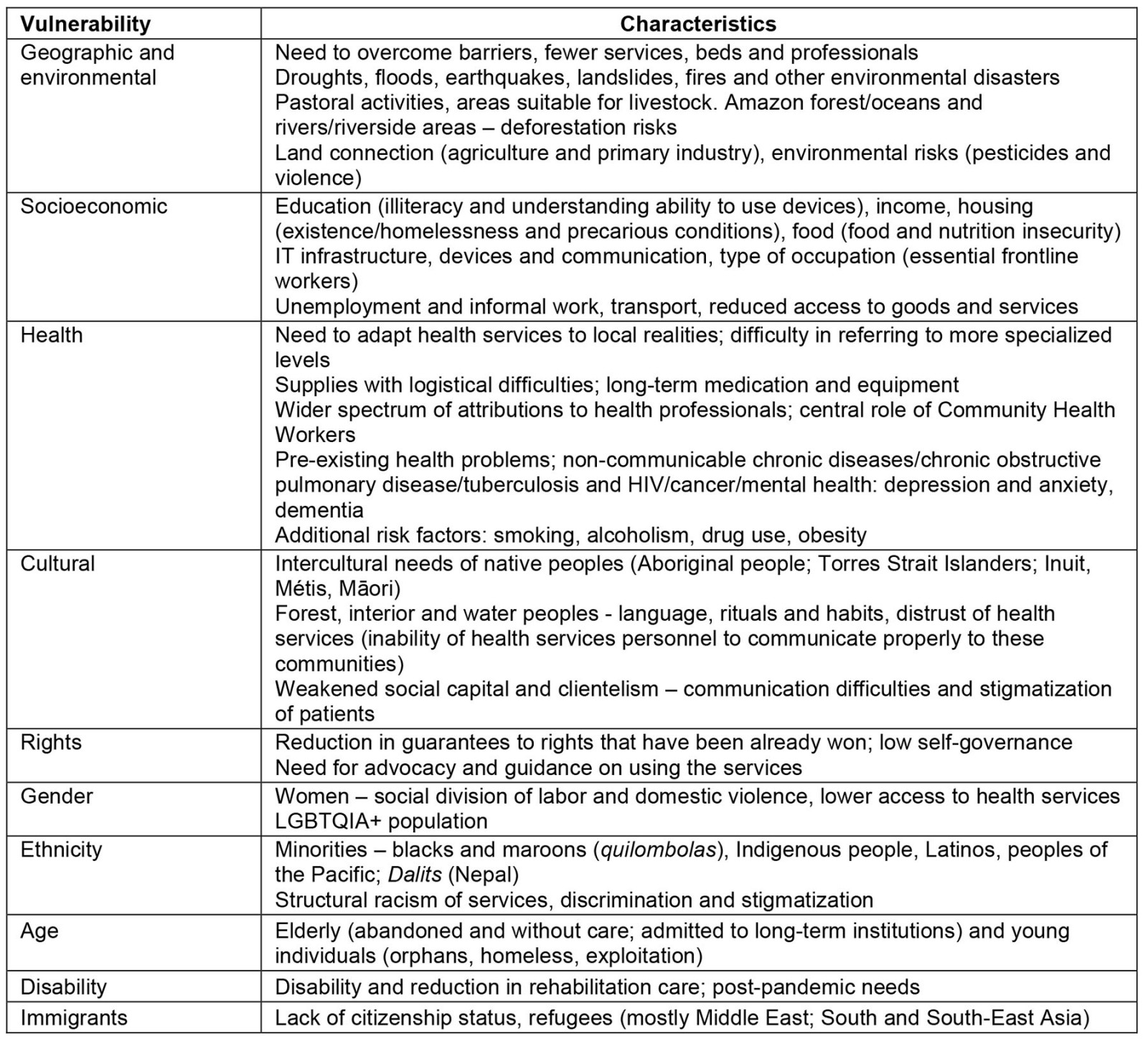

Table 4 presents the identified vulnerabilities, based on the approach of populations that are difficult to reach, called ‘last mile populations’66 and their specific vulnerabilities in rural and remote locations, which lack goods and services of all kinds, with health care being part of this context. Thus, all types of vulnerability found in the selected articles were aggregated.

Table 4: Top vulnerabilities found in the scoping review, by type

Figure 2: Word cloud of primary healthcare initiatives related to the COVID-19 pandemic in rural and remote locations.

Figure 2: Word cloud of primary healthcare initiatives related to the COVID-19 pandemic in rural and remote locations.

Figure 3: Word cloud of the description of rurality and remoteness.

Figure 3: Word cloud of the description of rurality and remoteness.

Discussion

The initiatives that are more specific to the rural and remote locations deal with communication with society, as well as different types of telehealth care, in addition to aspects related to the health workforce, such as training and strategies for attracting and retaining human resources22. Logistics and supply issues are also worth mentioning.

Not surprisingly, the least discussed issues in relation to rural and remote locations were the expansion of nursing and community health worker activities, which, although present, have a lower magnitude, since they are already routinely placed, even outside the pandemic period, and which has become a reality for non-remote locations in this context67.

Multiprofessional support, in turn, shows significant scarcity in rural and remote locations, and it is precisely in these environments that PHC health professionals end up expanding their roles and performing more complex actions locally, precisely because of the difficulty of interacting with specialized professionals68.

More recently, some studies have shown that the COVID-19 pandemic has broadened the medical curriculum, preparing graduate and postgraduate students with intersectoral accountability concerns and providing a reliable workforce in rural remote settings, with a PHC focus inside the community according to its needs25. In addition, some authors point out that, just as important as recruiting and retaining the workforce in rural and remote locations, is the maintenance of professional development and mental health support, which may help tackle these issues in the ongoing health workforce26.

As for the specific communication and access initiative, the COVID-19 pandemic has rapidly and dramatically changed primary care services in the short term, changing many visits from traditional face-to-face meetings to telehealth-only meetings53.

The comparison in the use of telecare before and after the pandemic shows that there was a considerable increase in urban regions, although it was previously more often used in rural and remote regions, as it occurred in Canada. This is due to the greater availability of technological infrastructure and the ability to use technologies. In rural and remote locations, there is a greater proportion of isolated elderly people with chronic diseases, who would benefit intensely from telecare, reducing their risks of contact and displacement, but the initiatives are hindered by the acceptance of this type of contact and, mainly, by structural obstacles54.

The study by Jetty et al showed that populations lacking healthcare, particularly in rural communities, are less likely to have access to the technology needed to support virtual video consultations53. Among the several reasons for demographic disparities in telehealth use are the distrust regarding the use of technology to obtain care, and poor health or a lack of technological literacy in seeking medical care, especially in relation to the technological engagement of patients aged 65 years and over, as well as among those with chronic conditions. Detailing this issue, Hanjani et al reported that these populations – the elderly and those with chronic diseases – had less contact with their family doctors and PHC services during the COVID-19 pandemic55, which puts them in a situation of greater isolation and vulnerability, including having increased health risks associated with drug use in unadjusted doses.

On the other hand, the authors argue that telehealth drug reviews can positively impact clinical and financial outcomes, through asynchronous communication such as email and text messages, which are well accepted by patients. Thus, rural pharmacists worked together with community nurses, using videoconferencing technologies to review medications, enabling their delivery to the patients’ homes55.

It can also be pointed out that asynchronous forms of communication were mentioned as an initiative that yielded high levels of satisfaction during the pandemic for both users and professionals (94–99%), especially for the management of diagnostic test results and prescriptions24. New models of assessment, such as virtual triages, were proposed, mainly to help rural, remote and underserviced areas, and those without a family physician, and they can be useful for vaccination purposes or in the long term27.

Considering that these technologies have been increasingly used to provide drug access and review services, particularly for patients in rural and remote areas, it is crucial to promote funding for all types of interaction and communication with users, and invest in education, training and inclusion of vulnerable populations to the use of telehealth services for a better quality of service delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic21,54. Some authors draw attention to a firmly, well established and inclusive telehealth policy in PHC delivery models, in order to reduce health inequities in regional, rural and remote localities56.

In the other dimensions, we depict the need for rapid test usage in public health, due to the great distances users have to travel to access more complex tests. Clinical initiatives address the reduction of risk factors, such as smoking57, related to the isolation of communities and mental health problems, in addition to remote treatment, which is so relevant in these areas, but still shows important infrastructure deficiencies. A novel approach in the set of initiatives in the clinical dimension was related to delivering time-critical COVID-19 antiviral therapeutics to individuals across large, remote and logistically complex regions. An Australian study evidenced that a variety of modes of transport were used to transfer medicines between these regions, not only efficiently, but also in a culturally safe way for First Nations people28.

In the intersectoral dimension, the main initiatives are focused on the One Health strategy, which unifies human, animal and environmental health, more evident in pastoral communities and localities58, and food and nutritional security, with the risks of shortages in remote locations, especially in those without sufficient agricultural activities69. On the other hand, there is a greater scarcity related to initiatives aimed at sharing information, reducing inequalities and articulating different levels of government, which ignore mostly rural or remote locations, regarding their specific needs.

The main managerial innovations are related to diagnostic telecare21,59, remote monitoring and treatment (including rehabilitation and mental health) and IT applications related to epidemiological and health surveillance, and interdisciplinary teaching and research aspects60. Innovations in telehealth are addressed in some studies as potential strategies to reduce inequities, since they are characterized as a resource that results in improvement in healthcare access59,60.

Other possibilities for innovation include opportunities to increase vaccination rates with community strategies, further expansion of the scope of practices carried out by nurses and family doctors, improving communication between PHC and other levels of care, and improving the logistics of essential health supply chains.

Moreover, the diversified actions of collectives and community associations evidenced during the pandemic allow the activation of a very comprehensive social network, highlighting the importance of maintaining a well-established bond with the community in non-emergency times too, as a way of strengthening PHC. Health communication and education actions, population-wise, reinforce the importance of social isolation and other factors to avoid contagion in the community and favor the identification of people in a state of greater vulnerability70.

Although a large rural population is affected by COVID-19 worldwide and in many developing countries rural settlements constitute a large proportion of the population compared to urban cities61, the focus tends to be on population risk and disease severity in high-density urban communities. Interestingly, much of the media coverage of case and death counts revolves around urban areas and city hospitals, with limited information on what happens in rural and remote areas, which potentially reflects on the difficulties when coping with the pandemic in these areas5.

Considering that the majority of COVID-19 cases will be mild71, the essential attributes of PHC10 reinforce its potential for the exercise of safe and favorable patient care in the context of COVID-19, since the dimensions of care, case monitoring and community articulation constitute important mechanisms for rapid response to the pandemic72, especially in rural and remote locations.

Cultural issues deserve to be highlighted, since in remote locations there are specific peoples, such as those living by the water, in the forests and interior, such as riverside populations, Indigenous peoples, maroons (quilombolas) and Aboriginal Australians. The geographical aspects and barriers to overcome, as well as environmental adversities73, are issues that must integrate the formulation and implementation of public policies. The pandemic has further highlighted this need, considering that central governments must create protocols and regulations that consider local diversities, being inefficient otherwise62. The greatest difficulties in accessing and navigating health systems have also become critical in coping with the pandemic. Post-pandemic health needs deserve special attention, particularly regarding mental health and rehabilitation, as well as the pressure exerted on health services due to the pent-up demand during the pandemic74.

Socioeconomic vulnerabilities were also exacerbated during the pandemic, given the damage caused to essential workers and their families, who were exposed without adequate protection and lost their lives, given the mistakes made when dealing with the pandemic, especially in its initial phase. Thus, situations of orphaned children, living on the streets and exposed to exploitation, have increased75.

Ethnic and racial vulnerabilities have increased, such as delays in caring for people with complications related to COVID-19, which were evidenced to disproportionately affect racial and ethnic minority populations. There were more deaths among black people and three times more hospitalizations of Latino ethnicities than of non-black and non-Latino people at the beginning of the pandemic63. Similarly, Logan et al demonstrated that, in rural areas of the US, there are significant disparities between white and black populations, with the latter showing higher mortality rates64. These disparities represent a confluence of structural racism with other social and economic factors that increase the risk of COVID-19 exposure and disease-related complications among demographically vulnerable populations.

Ethnic vulnerabilities are also added to migratory vulnerabilities23,58. For immigrant communities living in rural areas, issues related to the status of migratory legality have a different impact on access to health care. Latino migrant farm workers show higher rates of health disparities and occupational hazards, with poorer access to care due to a constellation of factors that are legal, financial, cultural and geographic in nature64. Other issues, such as social isolation, negatively affect Latino immigrants in US regions and lead to additional barriers to care and a higher incidence of mental health issues. Thus, immigration acts as a social determinant of health, which can negatively affect the wellbeing of these individuals, especially during a global public health crisis such as a pandemic.

Vulnerabilities of gender, ethnicity, capacity and citizenship status also intensified during the pandemic, with higher rates of violence and indifference by society, including in situations of structural racism in health services65. The elderly, with chronic diseases, also suffered from difficulties in care and continuity of care, especially those in long-stay institutions55.

Such social determinants of health and other structural vulnerabilities in rural areas greatly affect their populations, which results in higher rates of chronic and life-limiting diseases, lack of access to mental health care, and greater diagnostic and therapeutic difficulties for several clinical conditions, including infectious diseases64.

Limitations

The scoping review, while fully answering the research question, did not allow evidence for the effectiveness of PHC practices; however, the method offers a panoramic analysis of initiatives implemented internationally. From this perspective, we qualitatively evaluated the articles, so that we could provide a more consistent classification to readers.

The fact that we worked with only three languages (English, Spanish and Portuguese) also represents a limiting factor; however, during the pandemic, most articles were published in English, due to the need to share the findings quickly and globally. Less than 1% of the articles found in the first search were written only in other languages.

We found a relevant set of studies that, although not meeting the inclusion criteria, were very rigorous, and were still read for the discussion, as they showed some important intersections between pairs of the PHC, rural and remote, and COVID-19 triad.

Finally, we are aware of epistemic injustices brought by an imbalance in power relations. Health knowledge and its diffusion are still colonial, with many implicit hierarchical assumptions, sometimes without considering the cultural competences of people from rural and remote regions76. Thus, another limitation is that some successful experiences in less developed countries may not be present, due to inequalities in the production of studies and publications.

Conclusion

The research question was fully answered by the review, having identified public, clinical, intersectoral and, mainly, organizational health initiatives. It is important to point out that remote locations have great potential for intersectoral activities at the local level, due to the strong articulation that is necessary between the different areas. From the organizational point of view, rural and remote locations showed enormous flexibility to face the pandemic, regarding the different levels of care.

The distance between the different levels of government has been further intensified during the pandemic, in the formulation of policies and protocols that had to be adapted to rural and remote locations for their implementation. It would be very important to articulate the different levels, with the officialization of national public health agencies and plans adapted to each local reality, aiming at assessing their implementation for future crises.

The results highlight and synthesize the knowledge about initiatives and innovations developed to face the COVID-19 pandemic, within the scope of PHC, in rural and remote locations worldwide. Innovations and lessons learned are equally relevant for the strengthening of health services and systems. This issue is still quite limited, so it needs to be further analyzed in new reviews seeking evidence to assess the sustainability and effectiveness of the implemented measures aimed at facing post-pandemic difficulties and other adversities. Moreover, empirical research in rural and remote regions is essential to address health inequities in future health crises.

Acknowledgements

A. Bousquat is a Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico–CNPq fellow in research productivity.

Funding

S. Schenkman is a postdoctoral researcher thanks to grant# 2022/0546-1, São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

You might also be interested in:

2009 - Descriptive epidemiology of blood pressure in a rural adult population in Northern Ghana