Introduction

Acquired brain injury (ABI) includes conditions like stroke and traumatic brain injury (TBI), and is one of the leading causes of disability in working-age adults worldwide1-7. Depending on the extent and location of the injury, individuals with ABI may experience a complex combination of deficits in functional domains such as the motor, sensory, cognitive, perceptual, and emotional domains. These deficits often lead to long-term disabilities that limit activities and restrict participation in life situations8.

Healthcare professionals can play a key role in supporting individuals with ABI, not only in the acute phase but also in the longer term and in the re-establishment of everyday life9. However, individuals living in rural areas are less likely to receive adequate rehabilitation, as rural areas are known to be a challenging context due to distances from healthcare centres, travel time, lack of specialised services, and maldistribution of personnel10,11. Furthermore, individuals with ABI who are discharged to their homes tend to ‘fall through the cracks’ of healthcare systems, even in high-income countries12-14. In particular, there is considerable evidence that individuals with less severe ABI often experience a lack of professional support15-21. This is probably related to a tendency to discharge individuals with less severe ABI from hospital without conducting thorough assessments, offering inpatient rehabilitation, or planning for long-term care22,23. For instance, individuals without significant motor or language impairments may mistakenly be assumed to lack impairments24-26. Although more subtle impairments may go undetected in inpatient settings, it is common for ABI-related difficulties such as concentration difficulties, fatigue, depression, and psychosocial issues to become more apparent with the transition to everyday life in the community27,28. During this transitional phase, individuals with ABI and their significant others, such as spouses, partners, family members, and close friends, tend to become more aware of the lasting impact that the injury has on their daily lives29-37. However, many individuals with ABI and their significant others experience a sharp decline in support from the health and social care systems after hospital discharge12,21,22,38,39.

Numerous studies have highlighted the need to develop rehabilitation services that support individuals with ABI in the process of adapting to the consequences of ABI and returning to their valued roles and activities25,29-32,34-37,40-44. Working-age adults with ABI face unique challenges in terms of responsibilities and social roles8,45. Thus, they may have distinct rehabilitation goals and support needs. Previous studies have shown that the greatest long-term threats to the wellbeing and quality of life of working-age adults with ABI are social isolation, depression, inactivity, exclusion from work, and limited participation in leisure activities24,27,36,46,47.

Studies have reported that adults with ABI and their significant others require proactive services and persistent professional support after discharge home to help them overcome the diverse challenges related to family life, social participation, the return to work, and finances13,20. These aspects of life are included in the broad, multifaceted concept of community integration (CI), which also includes aspects such as being independent, belonging, having a home, and being involved in meaningful occupational activity48,49. Additionally, the CI process is characterised by inherent uncertainties, phase transitions, and adjustments that may occur over extended periods of time49. Although CI is increasingly recognised as the overarching goal of rehabilitation after ABI31,48-51, the concept of CI also challenges current rehabilitation practices to increasingly consider the multifaceted nature, non-linearity, and long-term perspective inherent to the CI process.

It is recommended that individuals with ongoing needs after ABI have access to appropriate and adequate outpatient or community-based services to achieve CI8,52,53. To provide comprehensive and cost-effective care for individuals with ABI, it has been proposed that rehabilitation services should be organised in coordinated regional networks and that needs that cannot be met locally should be directed to specialist services54,55. However, implementing such solutions in rural areas is complex for two interrelated reasons. First, the heterogeneous, multifaceted nature of impairments after ABI makes it necessary to tailor rehabilitation efforts to the specific needs of each person, which requires a coordinated involvement of practitioners, typically achieved through multidisciplinary teams34,56-59. However, such structures are unlikely to be locally available in rural areas. Second, it is generally accepted that rehabilitation efforts have the greatest impact when they are provided in a relevant context. Contextual knowledge and relevance appear to be particularly important for rehabilitation efforts aimed at promoting CI, as these processes are tied to specific individuals living in specific communities. Hence, there is a need for rehabilitation models that can resolve the tension between providing professional expertise on ABI and maintaining contact with the rural everyday context in which CI occurs.

In this context, the objective of this scoping review is to map and explore the current research literature to identify existing models for the provision of rehabilitation services that promote CI in home-dwelling adults with ABI living in rural areas.

Methods

This study was conducted in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute guidelines for scoping reviews60,61 and the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews62. The guidelines were developed on the basis of the framework first suggested by Arksey and O’Malley63 and later elaborated by Levac et al64. Prior to the study, a protocol to guide the process was developed and registered online in the Open Science Framework65.

Inclusion criteria

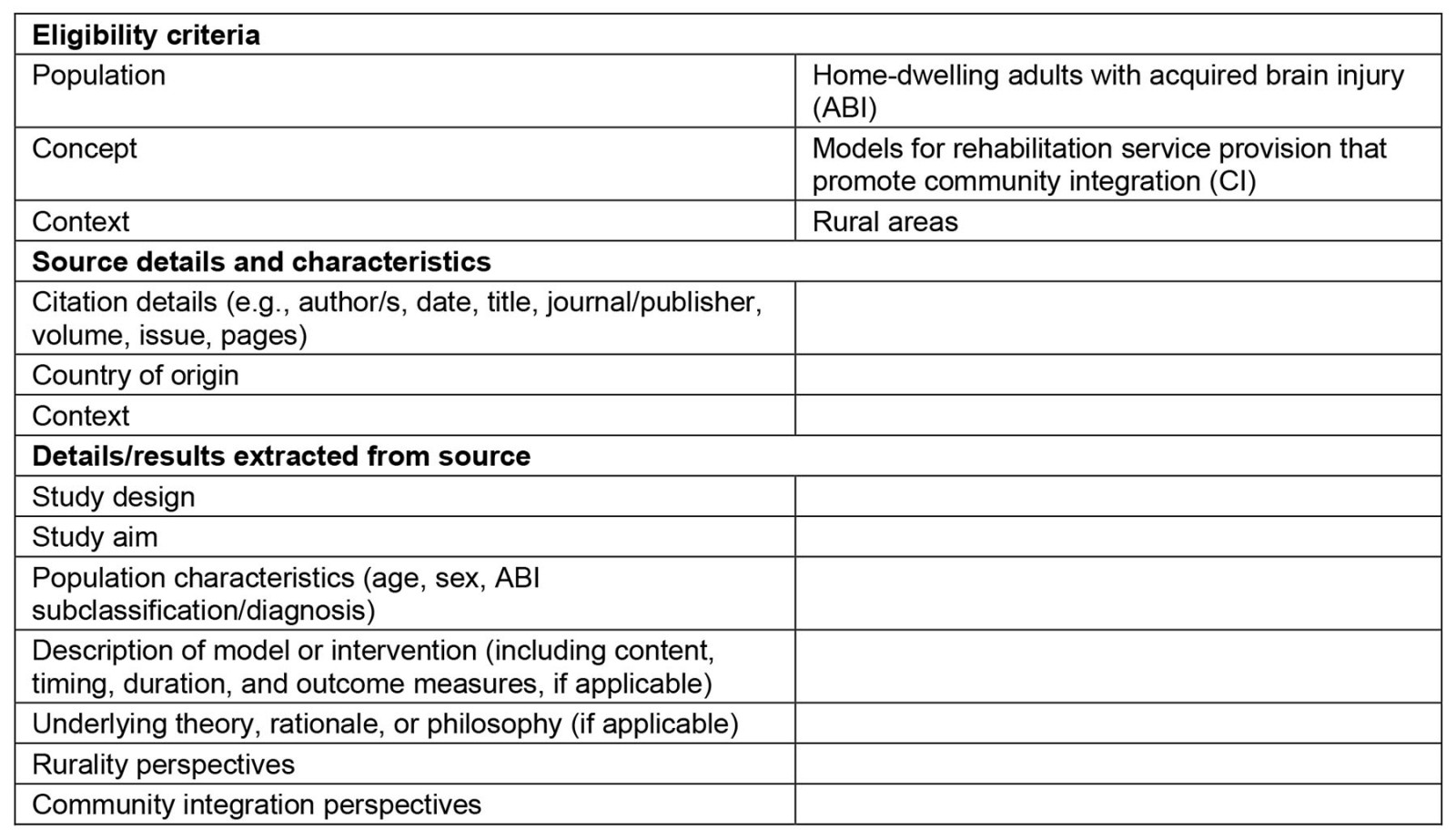

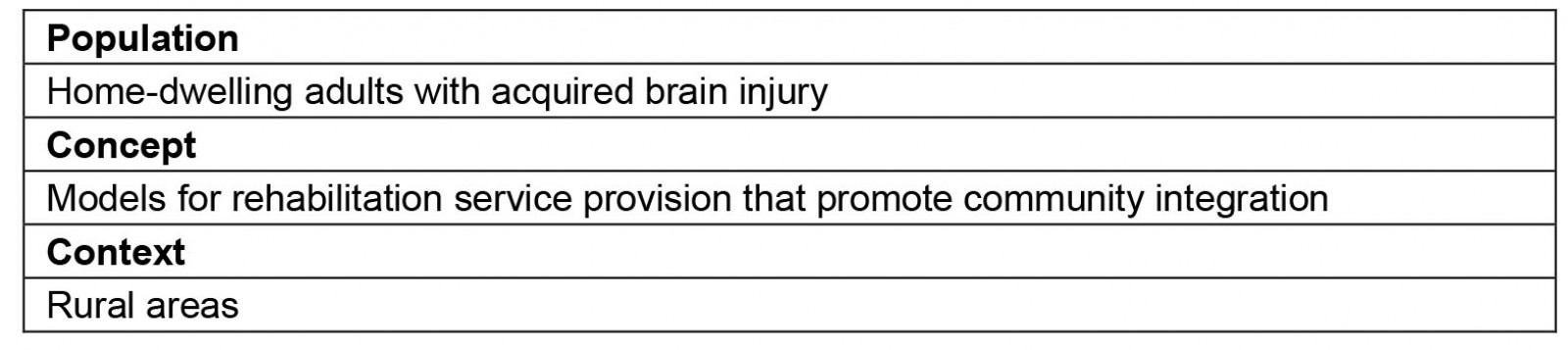

To be included, sources must describe models for rehabilitation service provision that promote the CI of home-dwelling adults with ABI living in rural areas. As recommended for scoping reviews, the development of the research question was guided by the Population, Concept, and Context mnemonic61 (Box 1).

‘Model’ is an ambiguous term that is often used without further explanation in the research literature. In this review, the point of departure was to consider the concept of ‘model’ in a broad sense as a simplified and systematic representation of certain aspects of the world. We concentrated on identifying models that express certain ways of organising the activities of individuals, organisations, or systems involved in the provision of rehabilitation services to home-dwelling adults with ABI living in rural areas. To identify relevant studies, the search strategy included related terms such as ‘framework’, ‘program’, and ‘service’.

This study considered all peer-reviewed sources that met the inclusion criteria, with no limitations on the study design, publication timeframe, or country of origin. Conference abstracts, grey literature, book chapters, editorials, and opinion pieces were not included. Only literature in English, Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish was considered for inclusion.

Box 1: Population, Concept, and Context elements guiding the research question

Search strategy

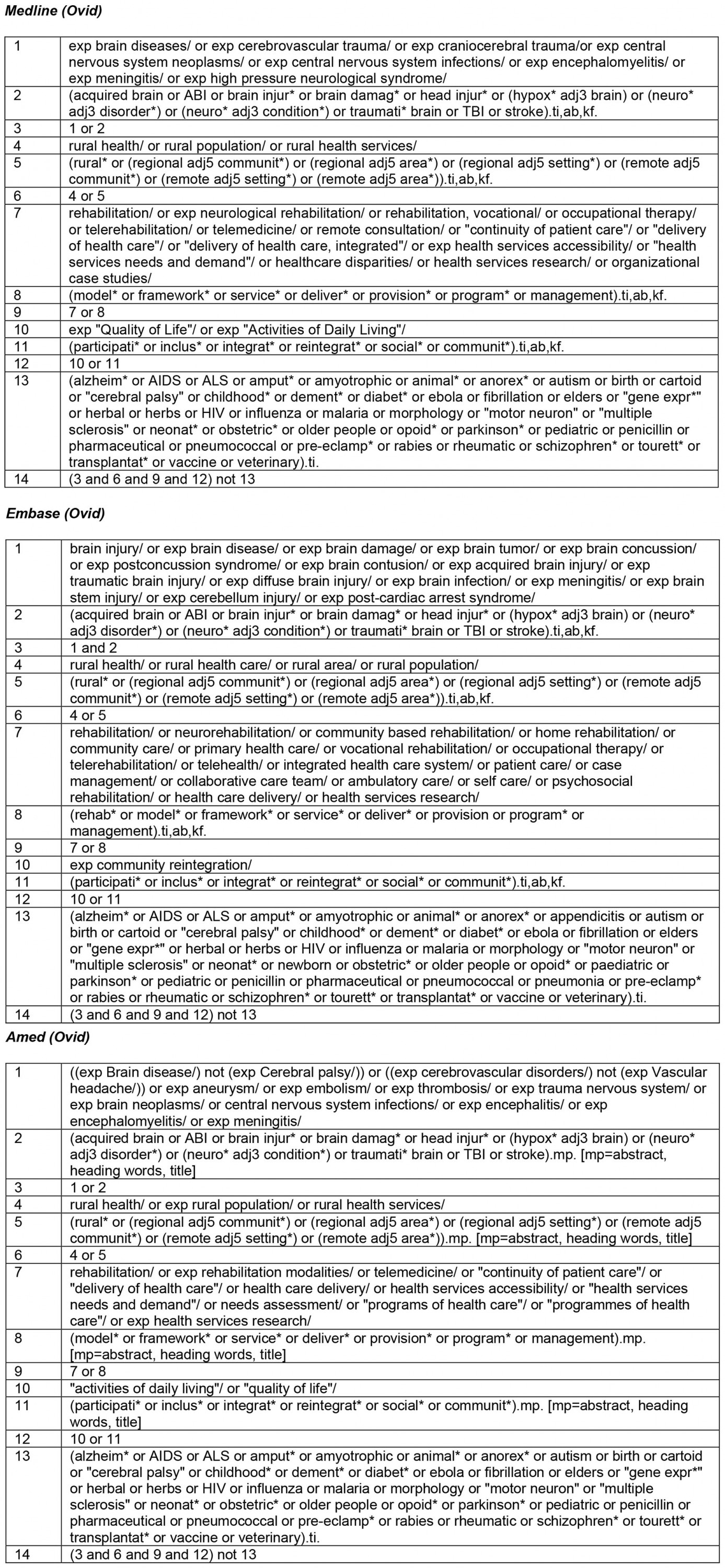

The searches were conducted in February 2022 in seven electronic databases: MEDLINE, Embase, AMED, CINAHL, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and PsycInfo. The same searches were repeated in January 2023 to discover new publications. The search strategy was developed by the research team in collaboration with an experienced research librarian. The development process followed the three steps recommended by Peters et al61. First, an initial limited search of MEDLINE and CINAHL was undertaken to identify relevant sources on the topic. Titles, abstracts, and index terms from these sources were screened to identify key words that were incorporated in a preliminary concept map.

Second, a full search strategy was developed. The search strategy was initially tailored to MEDLINE and then to the characteristics of the other databases. The complete search strategies for all databases are detailed in Supplementary material 1. The search strategy was also applied to Google Scholar to discover sources that were published after 2020 and may not have been indexed and available through the conventional databases.

Third, the reference lists of all included sources were screened. Furthermore, Google Scholar was used to locate and screen all sources that had cited the included sources (forward citation searching).

Source selection

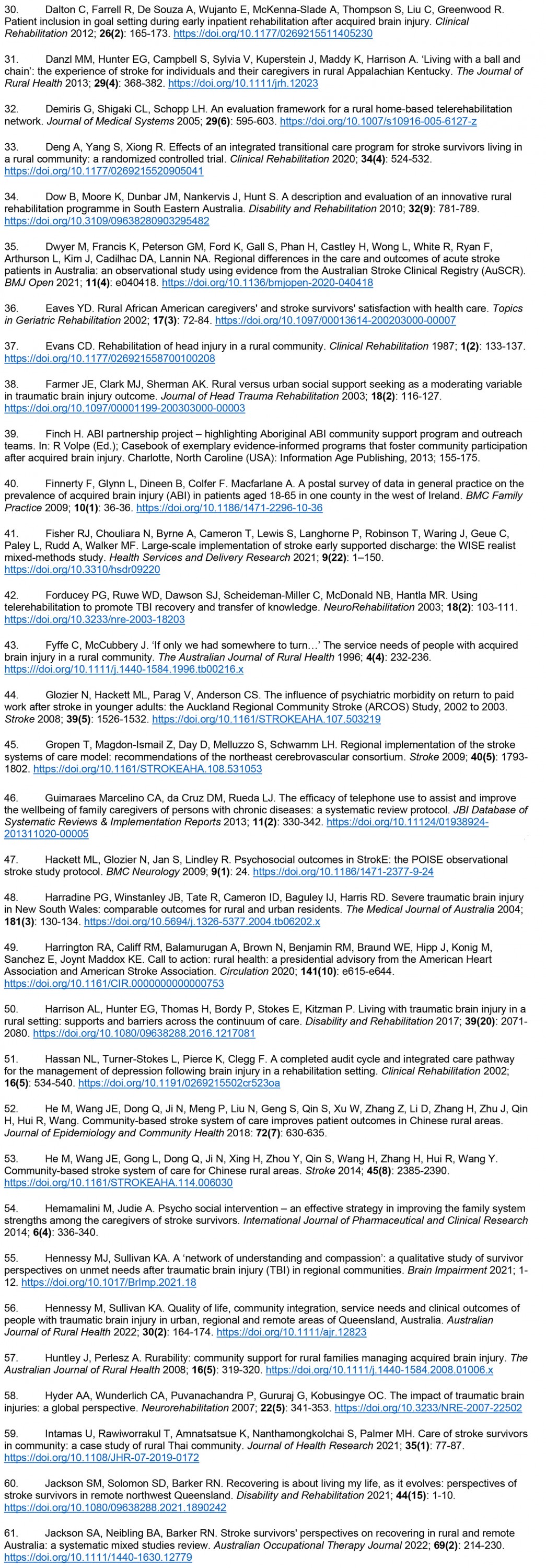

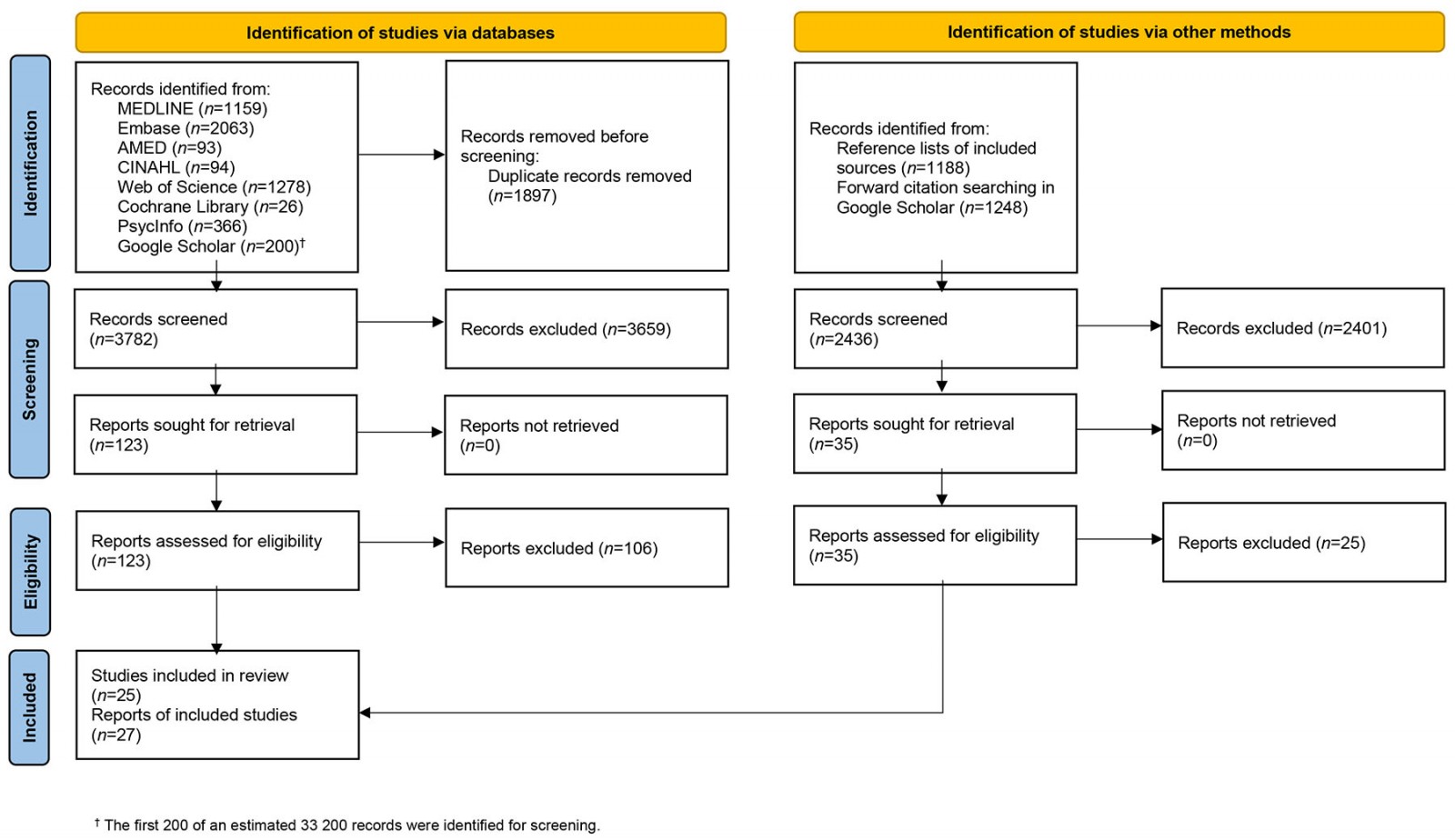

The initial search results were exported into Endnote software where duplicates were removed manually. After an initial pilot test to ensure consistency in the application of the eligibility criteria, two reviewers (MN and AG) screened all titles and abstracts independently using the Rayyan web-based application66 and excluded sources that did not meet the inclusion criteria. Full texts of potentially relevant sources were retrieved and assessed against the eligibility criteria. This process is outlined in a flow diagram (Fig1). The main reasons for exclusion of full-text sources were that they targeted the wrong population or wrong context, did not address CI, or lacked sufficient descriptions of model(s). A list of all sources that were excluded after full-text screening is provided in Supplementary material 2.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram of study selection process.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram of study selection process.

Data extraction

Data from the included articles were extracted using a data extraction form (Appendix I). A preliminary form based on the Joanna Briggs Institute template61 was developed for the protocol65. This form was piloted and revised by MN and AG individually by applying five data sources to assess and evaluate its usability and appropriateness. After making only minor adjustments and agreeing on a final version, MN continued to extract data from each of the remaining articles in close collaboration with AG. Both researchers read the full-text versions of all included articles repeatedly and continued to meet regularly during data extraction to ensure agreement throughout the process.

Data analysis and presentation

As recommended, the data analysis incorporated a numerical summary and qualitative thematic analysis63,64. The analysis was initiated by summarising the characteristics of each included article in a table to gain an overview and facilitate completion of the numerical summary.

The completed data extraction forms and the table provided a point of departure for the identification, mapping, and categorisation of the approaches to rehabilitation presented in the literature. The thematic analysis was iterative and evolved in response to the preliminary findings and research question. Agreement on the final categories was reached during discussions between the authors and rereading of the included articles. A critical decision during this process was to organise the identified rehabilitation model categories into micro, meso, and macro levels based on their primary sphere of influence.

Ethics approval

This study is a review of previously published literature and did not engage any human participants or collect primary data. Accordingly, no research ethics approval was required.

Results

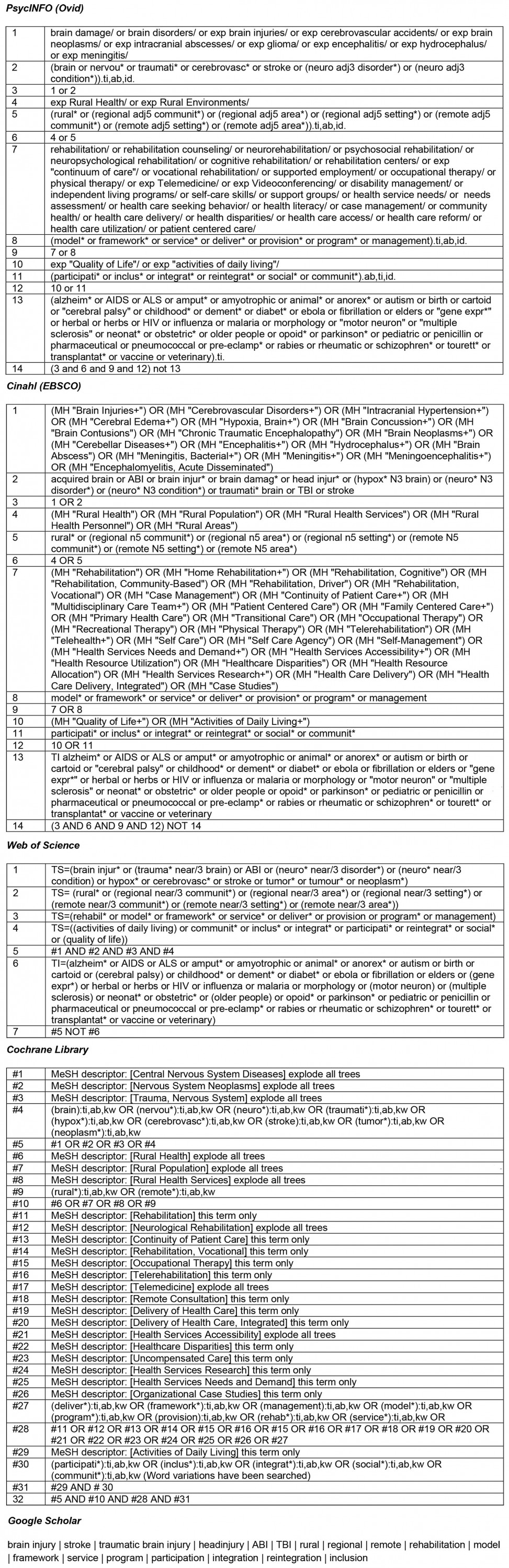

The database searches produced a total of 5679 references. After the removal of duplicates, screening of titles and abstracts, and review of full-text sources for eligibility, 17 articles were included. A total of 2436 additional references were identified via other methods. After the screening of titles and abstracts and review of full-text sources of the additional references, another 10 articles were included, resulting in 27 total included articles. The characteristics of the included articles are outlined in Table 1.

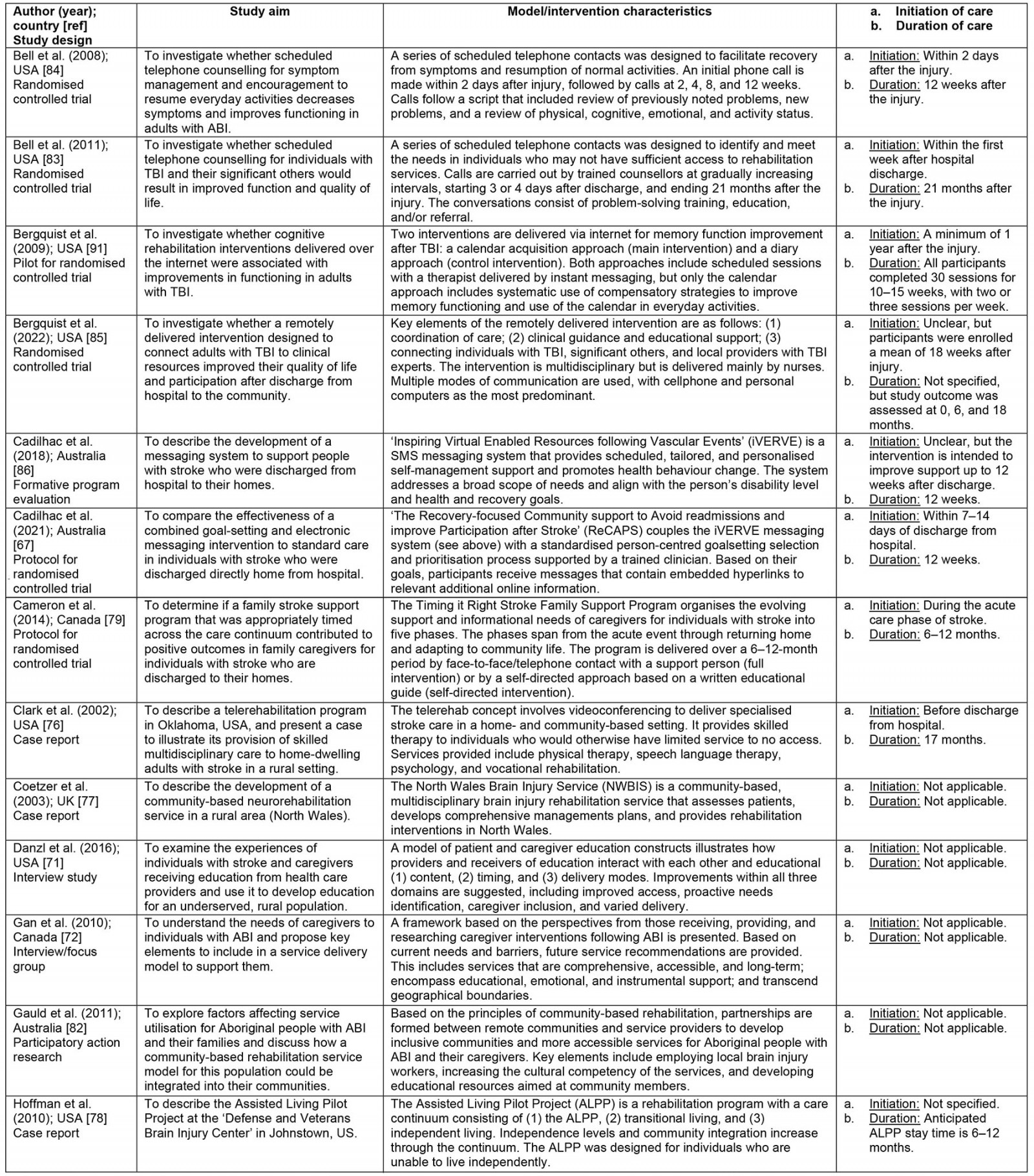

Table 1: Characteristics of included articles67-93

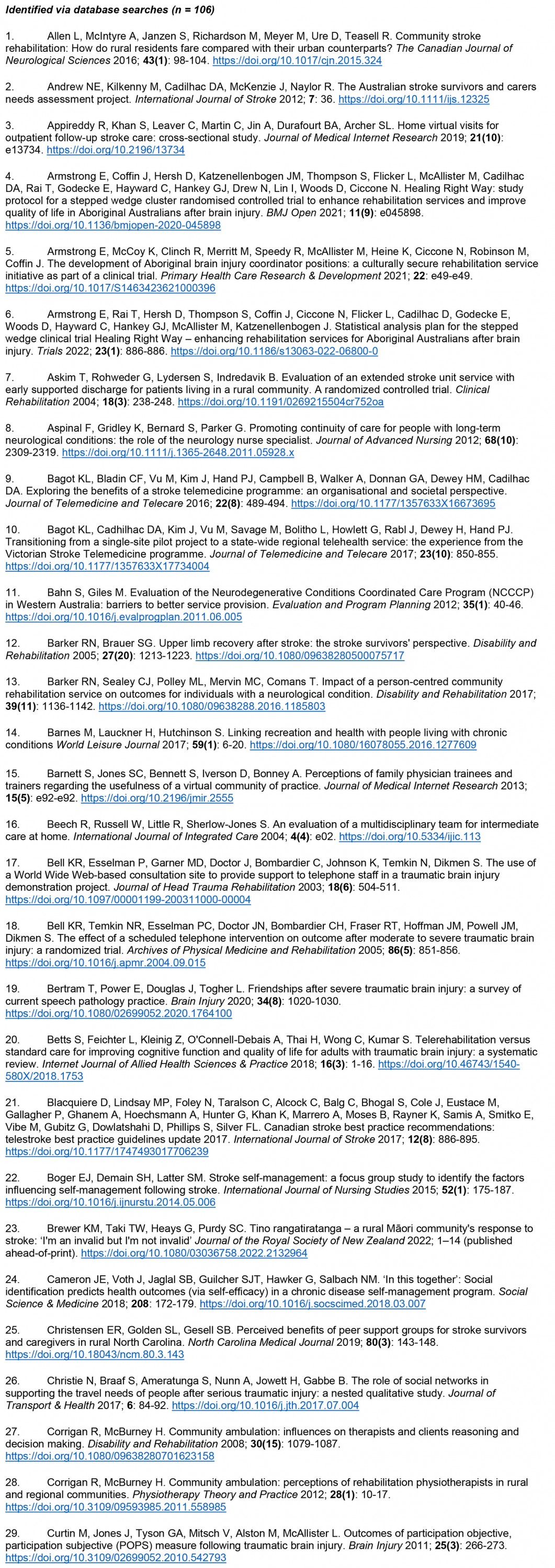

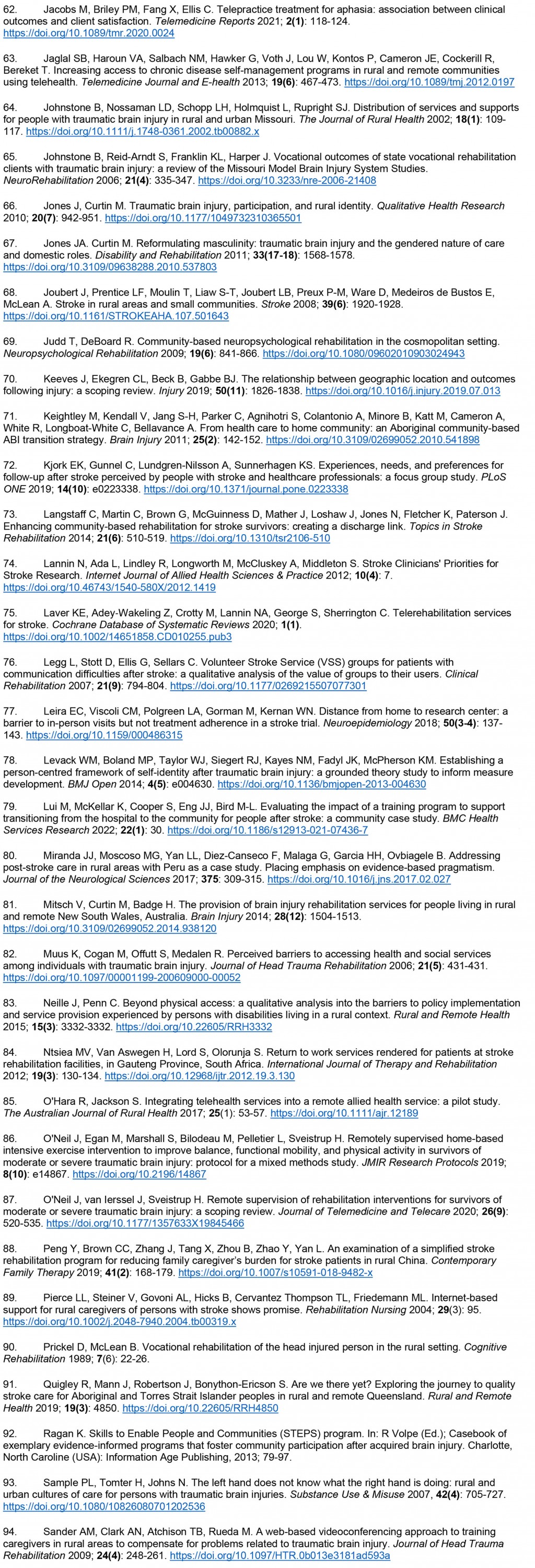

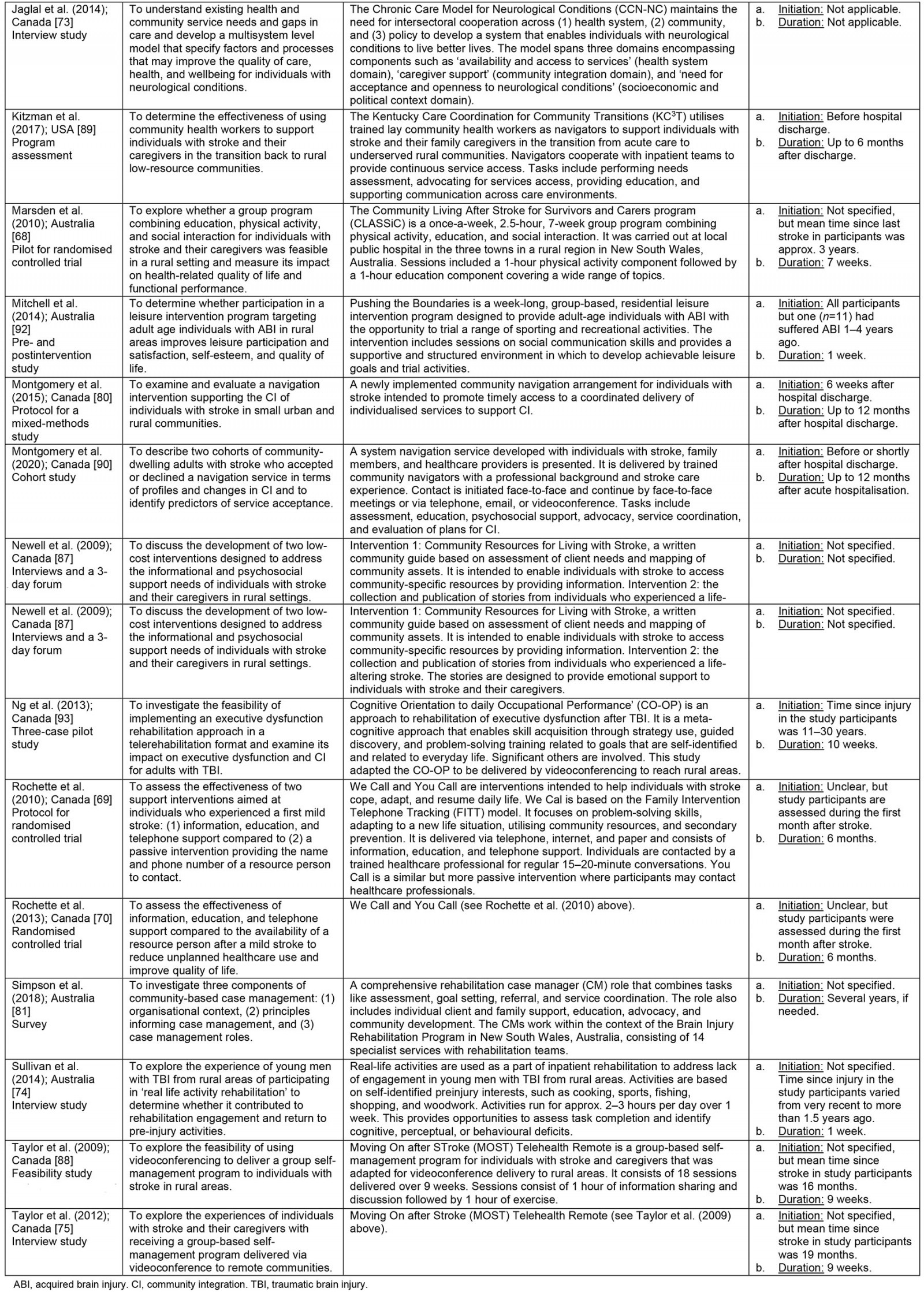

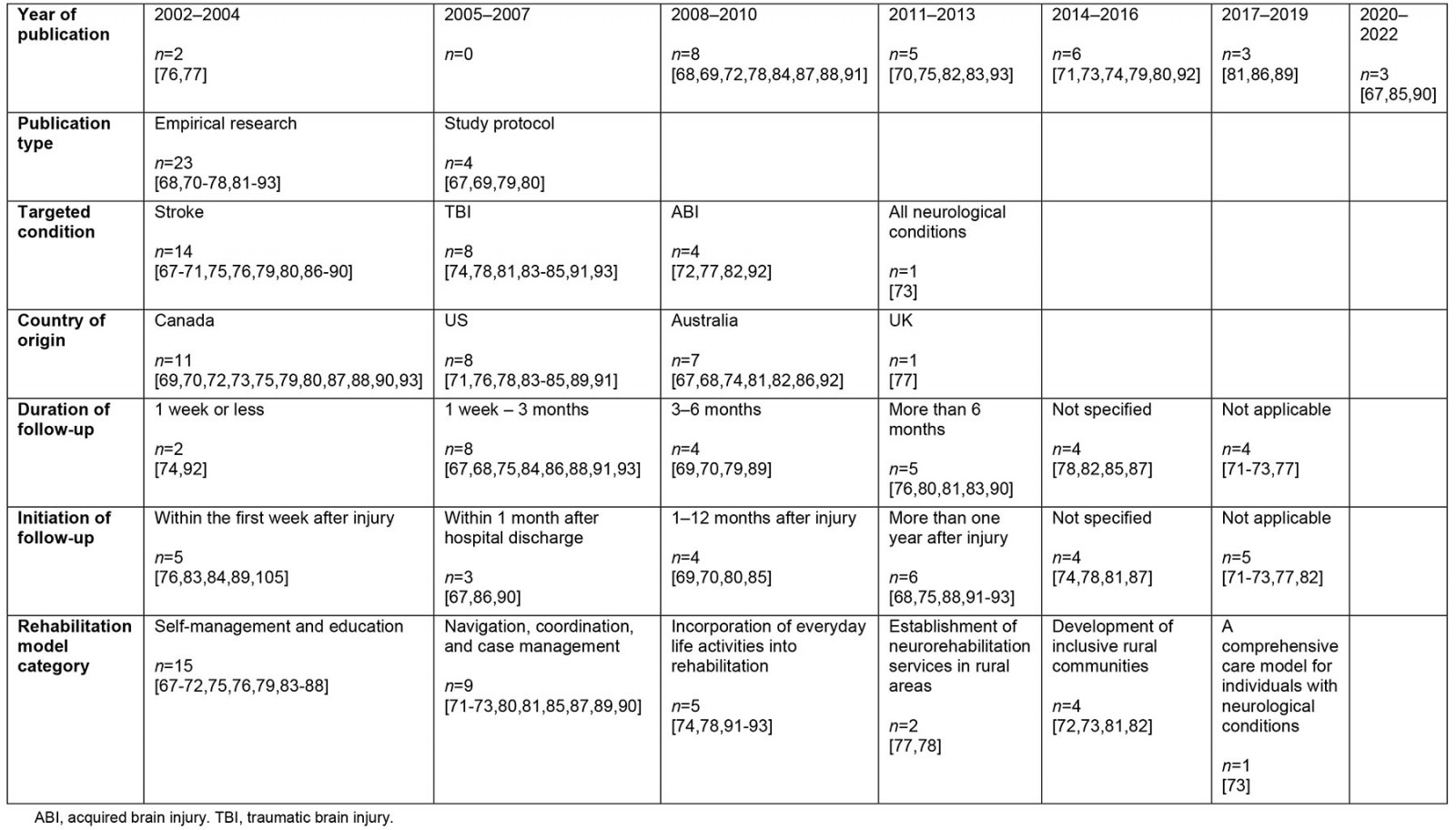

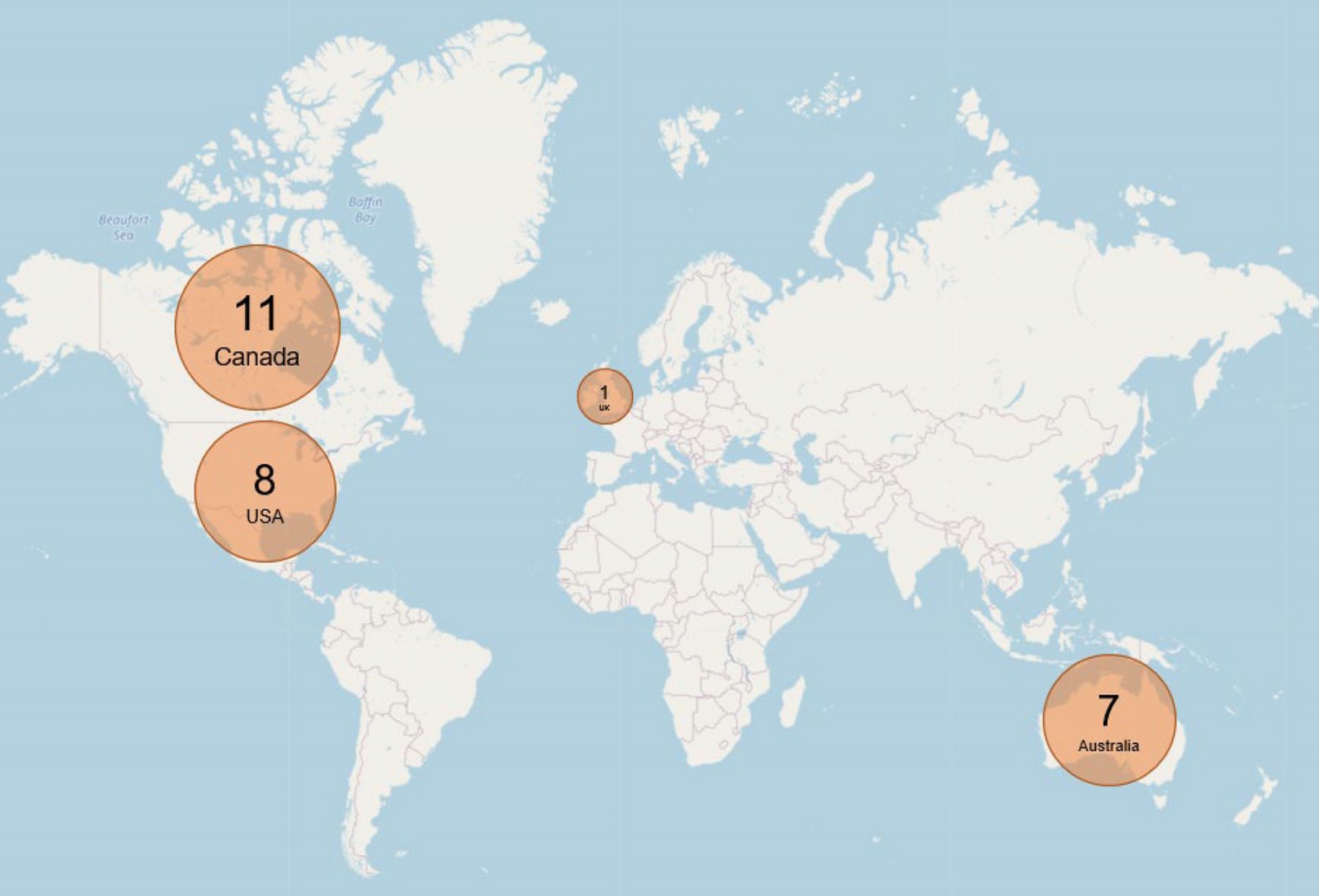

The numerical summary (Table 2) shows that the included articles consisted of 85% empirical research and 15% study protocols. The studies utilised a wide range of research methodologies, including randomised controlled trials67-70, qualitative interviews71-75, case reports76-78, mixed methods79,80, a survey81, and a participatory action research project82. All the included articles were published between 2002 and 2022. The most frequent condition targeted was stroke, followed by TBI and ABI (which may encompass both stroke and TBI). One of the included articles targeted not only ABI but all neurological conditions73. In terms of geographical distribution, all the included studies originated in Western and predominantly English-speaking countries with advanced healthcare systems (Fig2).

Table 2: Distribution of included articles by year of publication, publication type, targeted condition, country of origin, duration of follow-up, initiation of follow-up, and type of rehabilitation model categories67-93

Figure 2: Map illustrating global distribution of included articles.

Figure 2: Map illustrating global distribution of included articles.

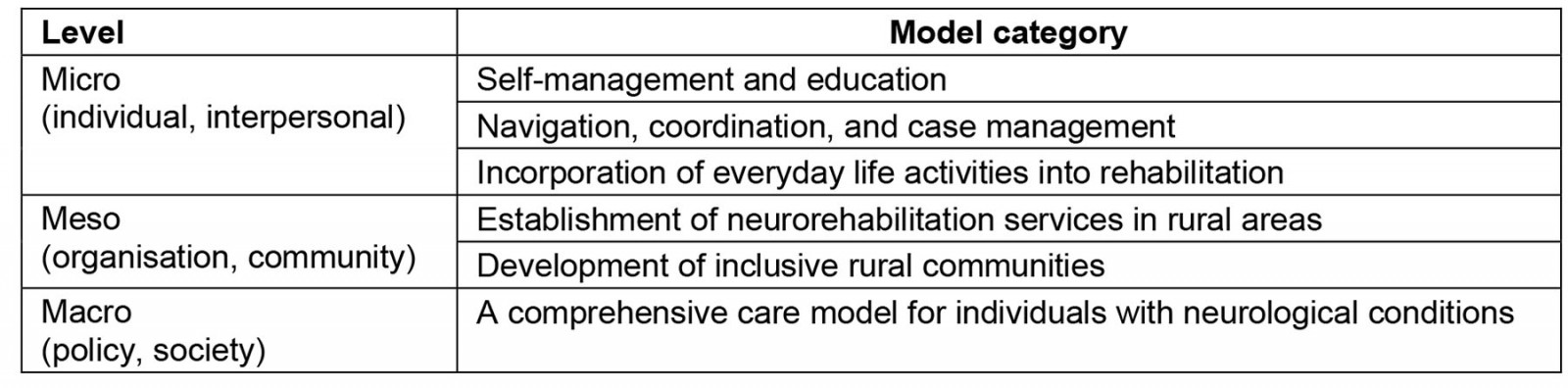

We identified six categories of models in the reviewed literature, each reflecting a distinct strategy for providing rehabilitation to promote CI in home-dwelling adults with ABI in rural areas. We further organised the models into three levels: micro (individual, interpersonal), meso (organisational, community), and macro (policy, society) (Table 3).

Table 3: Six model categories distributed across the micro, meso, and macro levels

Self-management and education

A substantial number of the included articles described approaches to promoting CI by enhancing self-management and providing education67-72,75,76,79,83-88. Six articles targeted individuals with ABI exclusively67,69,70,76,85,86, five targeted significant others alongside individuals with ABI68,71,75,87,88, and two targeted significant others exclusively72,79. Thus, the reviewed literature acknowledged that living with an ABI is a challenge not only for the person with brain injury but also for individuals close to that person. Challenges such as increased domestic workloads, reduced work participation, stress, loneliness, and uncertainty are common for significant others and may decrease their quality of life and hamper their ability to support the injured individual71,72,79,87,88.

Several studies examined the use of information and communications technology (ICT) to deliver self-management and education interventions to rural areas, including electronic messaging67,86, telephone calls69,70,79, video-conferencing75,76,88, and websites69,70. Other studies suggested the use of ICT to facilitate access to rehabilitation in rural areas, including web-based distribution of educational content71,87 and the establishment of online support networks72,85.

Some of the articles on self-management and education acknowledged that CI after ABI is a non-linear and long-term process, with support needs evolving over months or years71,79. Accordingly, they outlined rehabilitation approaches reflecting the importance of proactive identification of needs and appropriate individualisation, timing, and repetition of education. However, many of the articles on self-management and education did not describe or recommend follow-up beyond the first 3 months post-injury67,68,71,84-87.

Navigation, coordination, and case management

Using individual service providers to coordinate services and deliver care was one of the most common approaches identified in the reviewed literature. For simplicity, we decided to use the term ‘navigator’ here, as it appeared most frequently71,80,87,89,90. However, terms such as ‘case manager’72,81,90, ‘coordinator’71,73, ‘guide’81, and ‘advocate’80,81,85,89,90 were also used to describe similar types of service delivery. While some studies evaluated existing navigator approaches80,81,85,89,90, others were limited to making recommendations for future service design71-73,87. Interestingly, all articles describing existing navigator approaches were recent, having been published between 2017 and 202280,81,85,89,90. This may indicate that the use of navigators to promote CI in rural areas is an emerging approach.

The existing navigator approaches81,85,89,90 shared many traits. All emphasised individualised assessment to determine needs and goals as the basis for care provision. These approaches were also characterised by the involvement of the individual with ABI and significant others alongside service providers in the rehabilitation process. Furthermore, navigators performed a comprehensive range of tasks, including coordinating services, advocating for resources, and providing education81,85,89,90. However, only two articles explicitly discussed the initiation and duration of navigator support81,89.

The various navigator approaches operated within different organisational contexts: local communities89, a stroke outpatient clinic90, a regional network of brain injury services81, and a rehabilitation hospital85. All navigators had a background as healthcare professionals with experience in ABI rehabilitation81,85,90, except in one study where lay community health workers were trained as navigators89. The lay health workers had less expertise in ABI but used their local knowledge to assist with transitions from hospital to home. Reliance on lay health workers was described as an alternative to the recruitment of healthcare professionals, who can be expensive to employ and difficult to recruit in rural areas89.

Although team-based approaches to rehabilitation provision were not the main issue in any of the reviewed articles, several of the navigator approaches were associated with multidisciplinary teams. This included navigators integrated with regional community rehabilitation teams81, navigators linking community and specialist care teams85, and community-based navigators collaborating with inpatient rehabilitation teams89.

Incorporation of everyday life activities into rehabilitation

Five articles presented different approaches to incorporating everyday life activities into rehabilitation to promote CI74,78,91-93. One article described the integration of ‘real life activities’ into inpatient rehabilitation to address a lack of engagement in conventional rehabilitation activities among young men with TBI from rural areas74. Another article outlined a week-long program designed to provide individuals with ABI living in rural areas with the opportunity to try a range of leisure activities based on their own interests92. Two studies evaluated interventions addressing cognitive dysfunction following TBI. The first was delivered via telerehabilitation to rural areas and facilitated problem-solving training in everyday situations93, while the other was delivered via an instant messaging platform and trained participants in compensatory strategies for impaired memory in everyday situations91. Finally, one article described how vocational rehabilitation and social interaction could be integrated into a rehabilitation program focusing on gradual transitions to independent living for individuals with TBI returning to everyday life in rural areas78.

Establishment of neurorehabilitation services in rural areas

While many studies were conducted within the context of rural rehabilitation services68,74,76,81,82,85,87,89,90, only three articles described the development of neurorehabilitation services in specific rural regions77,78,82. One described the establishment of public brain injury rehabilitation services in North Wales starting in the 1990s77. A second outlined an ‘assisted living pilot programme’ at a rurally located rehabilitation centre that aimed to promote CI and self-supported living for US military veterans with TBI78. The third described the development of more accessible services for Aboriginal people with ABI by forming partnerships with remote communities in a region in Australia82.

Development of inclusive rural communities

Four articles emphasised community development to enhance the CI of individuals with ABI in rural areas72,73,81,82. One of the reasons stated for this strategy was the lack of public awareness and understanding of ABI72,73. Educating the general public and community members on ABI is suggested to dispel myths and promote acceptance, which can contribute to a more supportive environment for individuals with ABI72,73.

Increasing the capacity of rural communities to take care of their residents was suggested to alleviate some of the challenges posed by the long-term nature of support needs and long travel distances to specialist services. For example, one article presented a navigator approach that was not limited to matching client needs to existing services but extended to engaging in community development and finding new ways to utilise local resources81. Another example is the establishment of long-term partnerships between a regional rehabilitation service and remote communities to enhance the care capacity of the communities and adjust the services to match local needs82. These partnerships led to several improvements, including an increase in knowledge about ABI within the communities and improved ability of individuals with ABI and their families to voice their support needs. Additionally, the regional rehabilitation service enhanced its cultural competency and understanding of client needs and modified its methods for service delivery.

A comprehensive care model for individuals with neurological conditions

One article presented a comprehensive macrolevel care model for individuals with neurological conditions and their families73. The Chronic Care Model for Neurological Conditions (CCM-NC)73 is a further development of the Expanded Chronic Care Model94. The development of the CCM-NC was informed by user needs and service gaps as reported by policymakers and service providers across Canada. The model was not designed exclusively for home-dwelling adults with ABI in rural areas but rather represents a macrolevel view of the rehabilitation ecosystem. Nevertheless, CI is a key theme of the model, which has the overarching aim of creating an environment in which people with neurological conditions can live better lives.

The previous article73 also discussed specific challenges in rural areas, such as lack of access to specialist services, long travel times, and high transportation expenses. Suggestions to improve care include the increased use of telehealth and care coordinators, which is similar to solutions found in other reviewed articles, as well as the concept of mobile clinics.

The micro- and mesolevel model categories identified in this review seem to fit into subcomponents of the CCM-NC73. For example, the subcomponent ‘Acceptance and openness to neurological conditions’ within the CCM-NC addresses issues such as fighting stigma, which relates to the model category ‘Developing inclusive communities’. The subcomponent ‘Caregiver support’ in the CCM-NC emphasises support from significant others to promote the CI of the injured individual, which is similar to the model category ‘Self-management and education’.

Discussion

The aim of this review was to map and explore the research literature to identify existing models for the provision of rehabilitation services aimed at promoting CI in home-dwelling adults with ABI in rural areas. The overall results demonstrate that relatively few research articles have been published on this topic. The results also highlight the uneven geographical distribution of studies, with all 27 articles originating from only four Western and predominantly English-speaking countries. In part, this may be explained by the decision to exclude literature in languages other than English or Scandinavian, but it may also indicate a general need for more research on this topic in other countries and regions of the world.

Although the number of included articles was fairly low, the articles still described a heterogeneous range of approaches to rehabilitation. Despite this heterogenicity, we were able to identify six distinct model categories distributed across the micro, meso, and macro levels.

Uneven distribution of studies across the micro, meso, and macro levels

Strikingly, most of the included articles concentrated on microlevel issues such as intervention effects or perceived support needs. Far fewer articles addressed mesolevel issues such as organising services for rural areas or developing inclusive rural communities, and only one article addressed policy and society dimensions at the macro level. This suggests that research funders as well as the research community prioritises research on service delivery at the individual level rather than research that addresses issues at the meso and macro levels. This interpretation is consistent with previous claims that research on service provision to individuals with complex and long-term needs generally tends to focus on microlevel elements in overall care rather than more comprehensive efforts that are needed to develop or reorganise care systems95. The imbalance in research efforts is noteworthy because solely focusing on knowledge about individual-level service provision falls short in addressing the current healthcare system fragmentation. To enhance rehabilitation in rural areas there is a need for knowledge production that targets all organisational levels, including the gaps in meso- and macrolevel models identified in this study. Increasing research efforts targeting these levels may be particularly important to develop models for rural areas, where there is still a need for innovative ways of organising service delivery, developing inclusive communities, and creating policies that promote the CI of adults with ABI.

A need for increased awareness of support time and duration

With one notable exception79, there is a general absence of discussions on the timing and duration of support in the reviewed literature. This is surprising, as all the included articles to some degree were oriented towards CI after ABI, which in many cases is a long-term process with support needs that evolve over months or years33,37,49,96. The lack of explicit considerations of support timeframe is noteworthy because rehabilitation approaches that fail to consider the long-term nature of CI may fall short of promoting it. This indicates a need to continue to develop rehabilitation models that reflect the evolving nature of the support needed to promote CI.

Use of information and communications technology to reach rural areas

The use of ICT is widely promoted as a solution to some of the issues with care provision in rural areas97. Our findings indicate an increase in interest in and use of ICT to reach individuals with ABI in rural areas. This was particularly noticeable regarding approaches to self-management and education, perhaps because these kinds of interventions are relatively well suited to provide via ICT.

A further increase in the use of ICT to reach rural areas is to be expected with the continued spread and maturation of digital technology, simplification of user interfaces, and improvement in internet connectivity. With these developments, it will be crucial to support the use of ICT in individuals with ABI, as it may be complicated by their residual impairments. It is also important to acknowledge that the use of electronic social networks (ie social media, video-link services, and email) is currently regarded as an aspect of CI and should be supported in its own right49,98.

Team-based approaches are lacking, but navigators are prevalent

The lack of team-based solutions in the reviewed literature was surprising, as multidisciplinary teams are widely regarded as a primary structure for the provision of coordinated and compressive care to individuals with ABI57-59. However, a recent literature review demonstrated that access to multidisciplinary teams after hospital discharge is limited, not only in rural areas but also more generally33. It was concluded that there is a need to develop team-based approaches for long-term care provision to individuals with ABI33. Additionally, a recent Australian study suggested that the lack of access to multidisciplinary teams in a rural region may explain the increased use of navigators to provide long-term support to adults with ABI99. This is reminiscent of the findings in this review, in which team-based approaches to rural service delivery were found to be lacking, while navigator approaches were found to be plentiful.

The prevalence of navigator solutions in the reviewed literature corresponds with a considerable amount of evidence that indicates that individuals with ABI and their significant others want to be supported by someone who can provide care, coordinate services, and act as their advocate over time13,15,16,23,96,100-103. Navigators seem to be a response to the challenges created by the combination of complex support needs and fragmented care systems that are not designed to meet those needs, particularly in rural contexts. Although navigators may be an in-demand and appropriate model for service provision, this raises the question of whether their prevalence is a symptom of a wider system that fails to deliver coordinated and integrated care. Navigators may be a suitable first step to ‘glue the services together’ and harness existing resources to meet individual needs, but more comprehensive system changes may be desired in the long run.

The significance of supporting significant others

The importance of supporting and involving significant others alongside the individual with ABI was evident across model categories. This finding is consistent with extensive evidence of informal caregivers’ care needs as well as their significance for the long-term support of individuals with ABI13,19-21,103-109. Involving and empowering significant others may be particularly important in rural areas, where dependence on family and friends is likely to be greater due to a lack of available professionals with expertise in ABI. Although support from family and friends cannot be taken for granted or expected to replace professional care providers, support for informal caregivers seems crucial. This is important not only to prevent stress, burnout, and other negative health outcomes in caregivers but also to contribute to better outcomes for the injured individual13,105. However, support from health and social services is known to diminish in the later phases of rehabilitation21,31,33,38,105. Recent studies have reported that caregivers in rural areas experience substantial gaps in support when providing care for their home-dwelling family members with ABI, which contributes to a feeling of being isolated with their responsibilities15,110.

Community-service collaboration to co-produce care

To define ‘development of inclusive rural communities’ as a distinct model category may seem counterintuitive in a literature review that is not primarily oriented towards community development but rather towards service provision. However, our findings indicate that the interaction between health services and local communities may be vital to increase the capacity for care in rural communities as well as to drive service improvement. This was particularly striking in one of the included articles describing a community-service collaboration project that not only contributed to more inclusive rural communities but also enhanced regional rehabilitation services82. The prospect of mutual service and community development points towards an interesting interconnection between the two mesolevel model categories identified in this review: establishing rehabilitation services in rural areas and developing inclusive rural communities.

It has been argued that informal care provided by non-professionals in the community already represents a major source of care for individuals with complex and long-term needs. However, the current lack of integration and communication between professional and non-professional providers is suggested to increase care fragmentation111. Proponents of people-centred and integrated care have suggested that local communities can and should take more prominent roles as co-designers and co-producers of care and that their contributions are particularly valuable for promoting CI111,112. Increased recognition of community members’ contributions may be particularly valuable for improving care in rural areas, where formal providers tend to be ‘thin on the ground’113. However, the current debate on service delivery models has received criticism for excluding considerations of the role of informal carers by being too professional-dominated and service-centric111-113. Thus, increased involvement of community members alongside professional service providers may require a redefinition of their respective responsibilities111,113.

Increased community involvement in the coproduction of care may have significant potential to increase the rural capacity for care by drawing on existing community strengths, promoting local ownership of the solutions, and enhancing the professional support of informal carers113. Hopefully, future initiatives can harness the synergies and interactions between rehabilitation services and local communities to a greater extent. This may be a path towards improved alignment between services and communities, which can enhance the care for individuals with ABI living in rural areas.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study that has attempted to map and explore the research literature to identify models for rehabilitation service provision that promote CI in home-dwelling adults in rural areas. A strength of this review is the comprehensiveness of the literature searches, including the number of databases searched, the use of alternative terms to capture relevant literature, and the lack of time restrictions for publication.

A limitation is that the review concentrated exclusively on peer-reviewed published research literature. Although this strategy permitted a global scope, it precluded the identification of models described in other sources. Despite conducting comprehensive searches, we may have been unable to identify all relevant articles. For instance, some articles may have described solutions relevant for rehabilitation in rural settings without stating so explicitly and, thus, were not included in the review. Likewise, due to the broad and multifaceted nature of CI, it is possible that articles that address aspects of CI have used a different terminology and were not identified.

Conclusion

Models for the provision of rehabilitation services that promote the CI of home-dwelling adults with ABI in rural areas are a relatively unexplored topic in terms of research volume and the geographical spread of studies. It is striking that most of the included articles concentrate on microlevel issues relating to service delivery and perceived needs at the individual level. Far fewer studies address service organisation, community development, or policy and society dimensions, signifying a gap in existing models at the meso and macro levels. The results also indicate a need for more research that fully considers the long-term and evolving nature of CI after ABI, as this will increase the likelihood of developing solutions that adequately support it. Nevertheless, the existing research literature contains several models for service delivery, including self-management and education, the use of navigators, and the incorporation of everyday life activities into rehabilitation. Hopefully, the overview and analysis provided here can contribute to the spread, adaptation, implementation, and further development of the existing solutions in new contexts.

Our findings also suggest that the CI of adults with ABI in rural areas not only depends on professional individual-level service delivery but also can be promoted by supporting significant others, developing inclusive communities, and improving policies. More knowledge on these issues may facilitate a wider reorganisation of care systems to enhance the CI of individuals with ABI in rural areas. To produce this kind of knowledge, there is a need for more research that moves beyond the focus on microlevel service delivery.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Grete Overvåg, Head Librarian for Health Sciences at the Arctic University of Norway Library, for assistance with search strategy development.

Funding

This study was funded by the Northern Norway Regional Health Authority.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Supplementary material is available on the live site https://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/8281/#supplementary