'The mental health center is just not a safe place for me to come and share my feelings', Eddie blurted out as he sat across the table from the executive director of that very same mental health center. In his small town, having your pickup truck parked outside the local mental health center is not acceptable. Too much gossip, too much judgment. For a small business owner to be seen at the local psychologist’s office could damage a reputation and hurt business. America’s mental health was already in trouble1. With depression, anxiety2, and deaths of despair3 on the rise due to the impacts of COVID-19, identifying and supporting ways to get people connected and get them the mental health care they need is crucial.

How many pickup trucks in your parking lot? The line always gets my attention. Out here in rural eastern Colorado nearly everyone has a pickup truck. Even folks who don’t need a truck prefer to drive one. It fits in – it makes the statement that I belong here in the country. But you won’t see many pickup trucks parked at the community mental health center. Mental health, or mental, emotional, and behavioral health (MEBH), as it’s often called, carries a huge stigma in rural and frontier communities. In a world that solves its own problems, where just a few generations ago homesteaders took care of everything that assailed them and the stoic old rancher who picks himself up by his own bootstraps is a dominant image of success, paying too much attention to one’s mental health is just not that important. Or so we think. The images of toughness, independence, and self-reliance are so strong that they limit the care that might benefit many rural residents.

Rural communities also have a long history of strong community integration. Churches, clubs, Friday night sports, bowling leagues, bridge clubs, and coffee shop gatherings all have helped integrate community members across a broad sociodemographic spectrum. Sunday morning might find you in different churches, but Wednesday night you were on the same bowling team. And everyone joined together for Friday night football or volleyball. Communities benefitted from this integration of activities and people, ideas, and values.

‘Dis-integration’ of rural communities

Sometime over the past 30 years, many rural communities have experienced (or suffered) a loss of this integrated nature. The bowling alley closed, church attendance dropped, and the bridge club is just a few elderly women. It used to be that the rural community only got a couple of local TV stations. Now they can access the whole panoply of cable news, sports, movies, and shows, each with its own dire agenda.

The rural economy is changing from small family farms to larger corporations. Mining and milling are disappearing. Drought, with the added impact of climate change, hits in a cyclical pattern causing crop failure and economic crisis at regular intervals. International agribusiness and trade imbalance result in lost markets for crops and natural resources.

Alexander Leighton4, in his groundbreaking work My Name Is Legion, on mental illness and the community5, wrote that some MEBH problems are associated with, and may be caused by, human susceptibility to our community environment. It is not an individual’s fault they acquire a mental illness. Nor is it hard-wired into their DNA that they will manifest mental illness or emotional distress. The community may have more to do with an individual’s mental health and illness than we know, from exclusion due to differing beliefs, values, and lifestyles. Leighton described the concept of community ‘dis-integration’ as a general failure of the community functioning such that almost everyone in the population is exposed to stress. Leighton found that communities that were suffering dis-integration had higher prevalence and incidence of MEBH problems, including increased incidence of chronic persistent mental illness. Efforts aimed at improving community integration, helping everyone feel as if they belong and have a place in the community, resulted in lower incidence of MEBH problems6. In this work, integration celebrates diversity, and may overcome exclusion due to factors such as race, gender, income, age and marital status.

Historical and innovative ways to connect

Cowboy poetry was one such community method for stress management7. In the old west, cowboys and ranch hands assembled regularly to read and recite cowboy poetry8. Grizzled old ranchers and cowboys would get together and recite their cowboy poetry. Cowboy poetry was the spoken word of pain, poor health, death, love, hate, pride – all the emotions that make up a human. These gatherings were a safe venue9 for emotional expression and served the iconic, stoic old cowboy well through shared expressions of pain and fear, joy and sadness, loss and loneliness. These emotions could be shared in a safe venue10, processed, laughed at, cried at, and managed. Cowboy poetry was, and still is, a form of behavioral health care (Box 1, Fig1). While it may not be 'integrated' into the primary care practice, it can be integrated into the fabric of community life11.

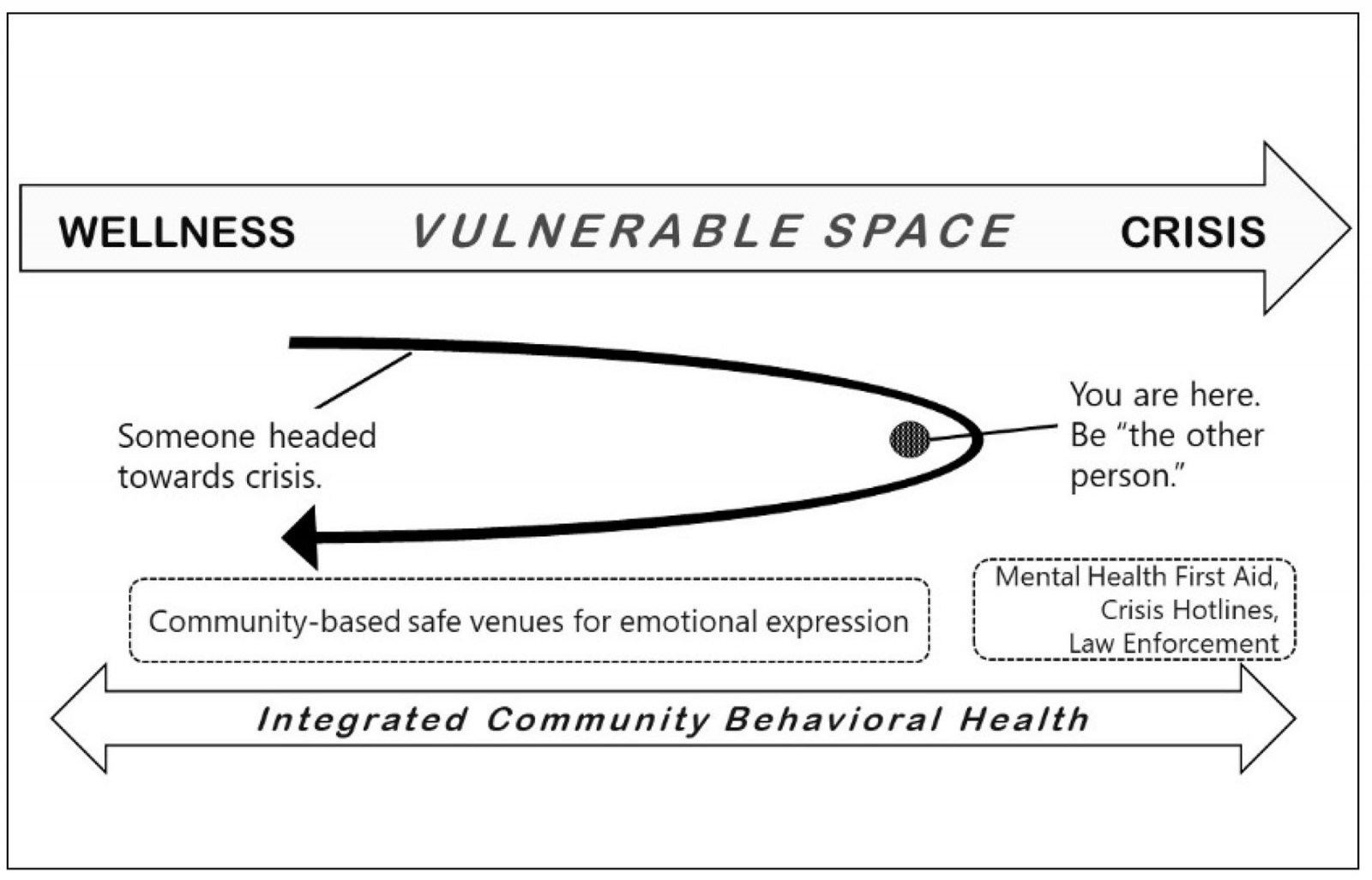

Cowboy poetry is just one example of this community-integrated behavioral health care. Many of the old standard community groups and organizations served a similar function12. Narrative behavioral therapy often uses storytelling, song, art and dance as methods for expressing emotion and telling our story13. And new ways are available as well. Finding and creating safe venues for emotional expression can help overcome a dis-integrated community and reintegrate individuals and groups in ways that support people in health and illness, in economic booms and busts, in wholeness and brokenness. Policies that expand a community’s belief of where, how, and why behavioral health services are delivered are essential for rural communities to enjoy the full benefit of integrated behavioral health care. Patel14 and others15 improved population mental health through implementation of lay health counselors that were not confined within the walls of the clinic. They taught lay community members some basic counseling so they could intervene early, changing the trajectory of mental status away from crisis and back towards wellness. The High Plains Research Network16 Community Advisory Council created a peer program to Change Our Mental and Emotional Trajectory (COMET17,18) based on a 3-year study of community behavioral health needs and local assets. Figure 2 provides a graphic representation of the COMET concept to change the trajectory of mental illness before it is a crisis.

With the rising tide of COVID-19 related MEBH problems, our communities need additional resources and ideas to mitigate unemployment, drought, floods, economic crisis, climate change, social isolation, and uncertainty. What are examples of safe venues for emotional expression? Where do these programs occur? What populations do they serve? Are there common elements that can be identified, disseminated, and supported? What are the policy implications of addressing MEBH outside the usual sites of care? How do we use current safe venues for expanded services? Can we integrate professional behavioral health providers into these safe venues, whether by teaching them how to write cowboy poetry or suggesting they join a pickup basketball game or play bridge? While COVID-19 kept us at a physical distance, punctuating decades of decline in social connection, can we connect via phone, video, and new small groups? Pickleball?

We encourage communities to engage local primary care, behavioral health, and public health organizations to move the conversation about improving mental health care into action. Whether in integrated primary care and behavioral health care, a mental health screening and referral as part of public health efforts, or just a conversation at the coffee shop or in the car on the way home from bowling, local solutions begin with connections between individuals and organizations. Given the widespread impact of COVID-19 – coupled with the increased frequency of fires, floods, and droughts, changing economic structures and income disparities, and increased aging populations with decreased youth – now is the time to engage just about everyone, pull the cap off stigma, and bring mental health into the other safe venues in our community. Now is the time to build out our parking lots to make room for more pick-up trucks.

Box 1: Ridin’ Borrowed Horses – by Tom Westfall, cowboy poet.†

Box 1: Ridin’ Borrowed Horses – by Tom Westfall, cowboy poet.†

Figure 1: Rider on the Platte River.†

Figure 1: Rider on the Platte River.†

Figure 2: Changing our mental and emotional trajectory.

Figure 2: Changing our mental and emotional trajectory.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank High Plains Research Network Community Advisory Council: Chris and Kaitlyn Bennett, Shirley Cowart, Fred Crawford, Ashley Espinoza, Maret Felzien, Garry and Connie Haynes, Mike Hernandez, Ned Norman, Mary Rodriguez, Sergio and Norah Sanchez, Kathy and Steve Winkelman, and Christin Sutter.

Publication disclosure

A portion of this commentary appeared in Everyday Health, 28 August 2018. https://www.everydayhealth.com. It is no longer accessible online.