Introduction

Background

The development of a rural medical workforce requires a coherent strategy that articulates a long-term vision and the proposed steps required to achieve the vision. However, undergraduate medical programs, a key component of workforce development, often evolve in a piecemeal fashion. Traditionally, long-established programs focused on preclinical didactic teaching of subjects such as anatomy and physiology, and then in the clinical years taught discipline and specialty topics1. Curriculum changes in these contexts are characterised by small iterations based on pedagogical developments, external funding and pressure. However, large innovative changes in medical programs have occurred, generally where programs in new locations are developed. Some prominent examples include rural-based medical programs in Australia and Canada2. One of the challenges for large urban-based medical programs is reconfiguring the structure of the program to meet the needs of rural communities.

Rural health issues

Significant differences exist in health outcomes between rural and urban areas in Aotearoa-New Zealand (NZ), and these differences are worse for Māori3. Rural areas have higher all-cause mortality and amenable mortality compared to urban areas3. Higher rates of cancers4,5, accidents6 and cardiovascular disease7 are documented in the literature. Contributing factors include different demographic structures with higher proportion of Māori (and the subsequent impacts of colonisation and racism)3, and higher deprivation8. Gender differences, with a higher proportion of males and a lower proportion of people aged 15–45 years in rural areas, further contribute to health inequalities3. One framing of rural–urban health differences is to view the differences as arising from compounding demographic inequities. While this explanation likely accounts for the majority of differences, other social determinants of health are also likely to be important contributory factors. These include differences in occupations and occupational classes, environmental factors, poorer housing stock, and poorer educational opportunities and outcomes. While the majority of factors have a negative impact on health outcomes, there are also positive attributes of rural communities. These rural–urban differences are an important part of a rural curriculum.

Rural medical workforce

The health disparities between rural and urban areas in NZ are compounded by rural workforce issues. The rural medical workforce is under significant pressure, heavily reliant on overseas-trained doctors, with a maldistribution towards urban areas. In 2020, according to the Medical Council Workforce Survey, only 7.2% of doctors worked rurally, which is disproportional to the rural population9. The pressure on the rural workforce is increasingly acute, with GPs leaving or retiring. In 2022, 41% of rural general practices had at least one unfilled GP vacancy (Grant Davidson, pers. comm. May 2022) and 29% of rural GPs intended to retire within 5 years; these figures are likely worse now.

Despite awareness of rural workforce pressures, there is little evidence that NZ medical programs are producing enough graduates intending to work rurally10. Rural secondary school students in NZ have lower educational achievement11. As a result they are less likely to enter medicine at the University of Auckland, with enrolments less than half of the expected population proportion (personal correspondence). Medical students, on graduation from a NZ university, are 37% less likely to have an intention to work rurally compared to when they entered medicine12. The most recent data on medical student outcomes show that only 7% of doctors at 8 years post-graduation work in small towns or communities13.

Recent University of Auckland rural approaches

The medical program at the University of Auckland was established in 1968. It is a 6-year undergraduate degree that admits approximately 257 domestic students per year, although this is increasing to about 300 students in 2024. The first 3 years are spent on campus in Auckland, a large urban city with a population of more than one million, and the final 3 years involve clinical placements predominantly in urban hospitals in other regions in the upper North Island of NZ. Students are expected to spend at least 1 year out of Auckland. Students undertake general practice and community health placements. These involve 2 weeks in Year 4, 5–10 weeks in Year 5 (the later, longer attachments being part of a regional–rural cohort) and 6 weeks in Year 6.

To address rural workforce issues, the University of Auckland has implemented a number of approaches. The first of these is based on the evidence that positive exposures to rural health in the undergraduate years are strongly associated with entering rural practice14. In the medical program, approximately 50% of general practice placements in Year 4 and Year 6 are in a rural setting, and this changes to about 25% in Year 5. Unlike other Australasian medical schools, there is currently no year-long rural medical immersion program.

Another important action to increase the rural medical workforce is admitting students with rural origins14. Some of the challenges in settling on a rural admission pathway are the differing definitions of rurality, including a subjective feeling of rurality, population density or size and the commuting distance to an urban centre. The University of Auckland has a Regional Rural Admission Scheme (RRAS), which was previously based on territorial local authority boundaries. This scheme limited opportunities for rural students entering the medical program, because rural and regional students are combined in the same admission pathway, and the capped number is less than the population proportion living in rural areas. From 2024, RRAS will use a modified version of the Urban Accessibility classification to determine student origin11. Within this classification there are urban, regional and rural categories. The regional category encompasses urban areas that are distant from major urban centres, as well as semi-rural areas surrounding major urban centres. ‘Rural’ is defined as not being a large or major urban area and having medium or low urban accessibility. RRAS numbers will increase to match the population proportion for regional and rural areas.

Despite having a number of rural placements across the clinical years and a regional–rural admission policy, there is little indication that these have resulted in an increase in medical students from the University of Auckland wanting to pursue a rural career12.

The aim of this project is to inform development and implementation of a rural strategy. The research question is ‘How can an urban-based medical program implement a rural strategy?’ Evaluation of a rural strategy may lead to the strategy’s ongoing improvements designed to increase the rural workforce.

Methods

This is qualitative study involving semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders. The intention is to enable systematic identification of the processes required to develop a rural strategy, including possible facilitators and challenges that needed to be addressed, and will provide insight into the experiences of those involved in its development, including what they see as the strengths and weaknesses of the various rural programs, what might be done differently, and their expectations of the programs including their long-term vision. This knowledge will help inform and refine theory in this area.

Positionality

A critical approach is taken with this study. Critical research is designed to not only understand social reality but also change it15. The critical assumptions taken with this study were that rural inequities exist, that these inequities are driven by urban privilege16 and that researchers need to challenge their own roles in maintaining these inequities through self-reflection17. One of the challenges in undertaking critical research is the positionality of researchers, the forms of power that they hold and their insider/outsider status18. In this study the first two authors are academic GPs involved in the establishment and operation of a number of the rural and medical programs at the University of Auckland. The third author is a PhD student who has had no involvement in any rural or medical programs. A number of strategies were undertaken to ensure that the research maintained a critical approach.

Participant recruitment

The first strategy related to taking a purposive sampling approach in order to ensure that stakeholders held diverse and critical views19. Key stakeholders involved with the rural program (rural general practice and hospital teachers, medical program staff with a regional–rural role and rural liaisons implementing the extracurricular activities) were identified by KE. Diversity was sought by including both internal university employees and external stakeholders. To reduce any sense of obligation or pressure to participate, they were emailed an invitation to participate by an administrator, not by the investigators. Those interested replied by email and were then contacted by the research assistant (JW) to schedule a time for the interview. Participants were provided with information sheets, were given assurances that their identity and participation would not be discoverable by the GP academic investigators, and their oral informed consent was recorded at the start of the interview.

Semi-structured interviews

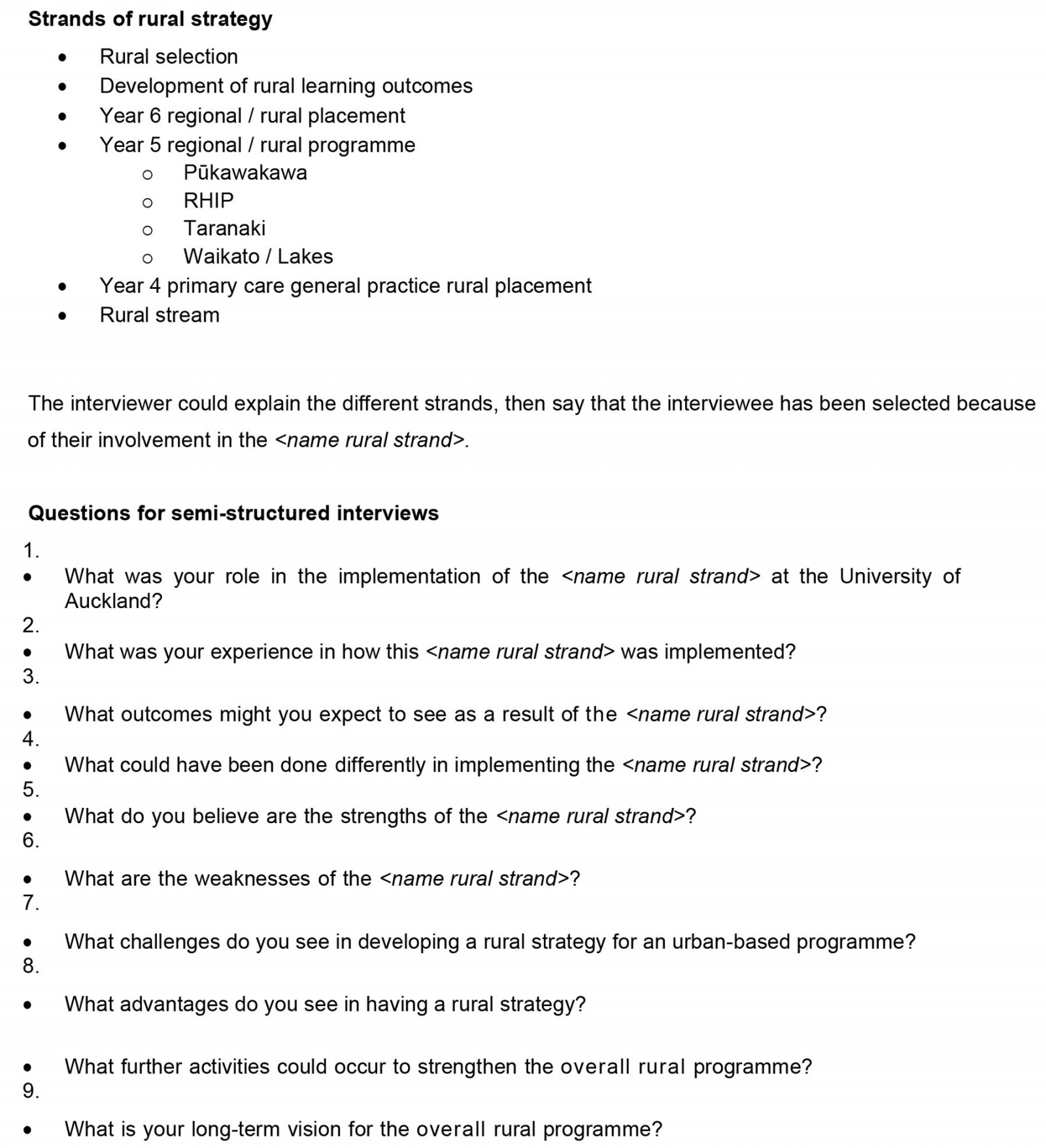

In order to ensure that critical reflection was generated by the participants, an interview schedule was developed that specifically asked about weaknesses and aspects of the programs that could have been done differently. The interview schedule also asked about participants’ experiences with the rural programs, strengths and long-term vision for the rural curriculum (see Supplementary material 1 for interview schedule). Semi-structured interviews were conducted by JW, who was not known to the participants. Interviews conducted via Zoom or telephone were recorded and transcribed. Transcriptions were de-identified including the role of the stakeholder, and each participant assigned a number (P1, P2, etc).

Analysis

A qualitative analysis of the de-identified data was conducted using a thematic approach20. Interview text was imported into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, with individual paragraphs placed in separated cells. Each paragraph was read and raw codes were assigned to the text. The first two interviews were independently coded by both KE and FG. Following sharing of codes and discussion, the remaining interviews were coded by FG. The transcripts and raw codes were re-read again and synthesised into focused codes by both KE and FG. Finally, overarching themes were developed through further synthesis of the focus codes and discussion between authors. In developing themes the authors paid attention to text generating discomfort or providing constructive critique.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee on 1 July 2021 (reference number UAHPEC22412).

Results

Fourteen stakeholders were interviewed: four rural GPs, two rural hospital doctors, four administrators involved in placing students, and four senior medical academics with involvement in the regional and rural programs. Further demographic details were not collected, in order to minimise the investigators’ ability to identify specific interviewees.

Five overarching themes were identified: (1) developing rural pathways into medical school, (2) improving and expanding rural exposures, (3) developing rural GP pathways, (4) implementing interprofessional education and (5) having a social mission.

Developing rural pathways into medical school

Having a functioning rural admission scheme was commented on by a number of participants. Although the University of Auckland has implemented a new admission scheme for rural students, there were questions around the selection process of the students. Some participants felt that aspects of a student's life experience and personal characteristics were important and should form part of the selection criteria.

… to me the way we select our students needs a real overhaul in terms of, you know, that life experience in rurality and focusing on those, you know, yeah, the particular population groups that need more help. And therefore, when they come into our rural areas, they’ve got greater connection and greater affinity to what’s going on. (P5)

One important characteristic that participants felt should be included was empathy and communication skills.

I want the guys who are humanitarian, who are empathetic, who have social skills, who have people skills … So, that’s a different subset from the people who are going in there now. And, I’m not disparaging to them, because we need them too. What I’m saying is that there is another cohort of individuals who never get near the med school who would make fantastic generalists in healthcare. And, this undermines all of the efforts for those who are trying to make the rural strategy work when the cohort is not ideal. (P13)

Some participants questioned whether the University of Auckland was even suited to teaching rural health due to its selection processes and should simply focus on training urban students to be urban hospital doctors.

We certainly need lots of urban doctors in hospitals, so maybe Auckland isn’t really the right place to be doing the rural thing. (P1)

Other solutions in developing rural pathways included the university having greater involvement in rural secondary schools, with mentoring and support of rural youth.

Improving and expanding rural exposures

A number of issues were identified relating to rural placements and programs when students entered into the medical program. Most participants mentioned the importance of rural placements and that there was a need for rural exposures to attract students into rural careers. While some saw the need to attract non-rural origin students into the rural workforce by giving them rural placements, some thought that rural programs should only be offered to students who wanted to do rural placements, and in particular to prioritise students who came from particular rural areas to enable them to go back there.

I would rather have invested in people who are keen on the opportunity of training in rural medicine, or at least, you know, at this stage, they have enthusiasm for the possibility even if finally they don’t end up going through it. (P6)

While some participants talked about focusing on rural students, other participants had slightly divergent ideas and talked about the need to train for a variety of careers.

We’re not just saying in contrast we only want rural doctors. We’re trying to create rural doctors, academic clinicians, scientists, all sorts and so that’s one of our challenges. And so it’s always going to be a slight compromise as to what we do. (P12)

A key component of expanding rural exposures was establishing year-long rural placements. These placements should occur in genuine rural locations to give students exposure to the community and to feel part of a team.

So at least a year-long placement in a rural place. That’s where the international and New Zealand based evidence is where the outcomes are best. (P9)

Development of rural structures

While most participants felt that increasing rural exposures for students was a critical element, it was thought that this needed to occur within a suitable structure that was rurally focused. There were two ideas relating to improving the university structure.

The first structure was the establishment of a national interprofessional school of rural health. This was held up by some participants to be a vehicle for implementing their rural pipeline aspirations.

I mean, very high on my wish list is that national interprofessional school of rural health … you know, with the reorganisation of the health system, this is the perfect opportunity to embed that into that reorganisation. (P6)

The national interprofessional school of rural health would result in a national approach to rural undergraduate and graduate teaching and a way to break down the silos created by the universities for placement locations.

There’s people from Northland who want to go Otago [University], but, then want to work in a rural place, as an example, but, can’t [do a placement] in a predominantly Māori community because they’re in Otago which is ludicrous. (P9)

Rural clinicians did not see the silos and tribalism created by university structures as helpful.

I mean we’ve always tried to act in the national interest, so we try to avoid tribalism. We try to avoid patch protection and we try to work collaboratively and let’s decide what’s in the national interest and then go from there. (P12)

Not all participants saw a national interprofessional school of rural health as being the solution to addressing rural workforce issues. A couple of participants mentioned that a third medical school proposal, based in Waikato, had some potential strengths.

Yeah, it would be even better if there was to be a separate hub that it was actually genuinely rurally based. (P1)

The other structure that participants discussed was increasing the rural academic footprint in order to develop rural pathways, develop rurally focused research and strengthen interprofessional learning.

One is that we don’t have enough rural academics embedded in rural areas. Two, I think we need more infrastructure. Three I think we need more flexibility to recognise that learning can occur in any setting and be accepting of that. Inter-professional learning could be strengthened for certain. Research could be strengthened for certain. But, those things only come into play once you’ve got academics embedded in those rural areas. (P12)

Although the university had established a small number of rural academic positions, one participant felt that this was too late.

I guess strengthening the number and amount of academic [full-time equivalent] based in rural areas and like for example you know having that symposium and input into their students, their online resources and forums and things. I think that’s probably a missed opportunity and … probably should have been started a bit sooner. (P9)

This participant also felt that there was a disconnect between the university and rural clinicians and that increasing rural academic capacity would be helpful.

Which I guess speaks to a little bit of my previous point around disconnected from the campus and not feeling resourced enough to participate in the department. So it’s developing that academic capacity in all its forms so teaching, research and service. (P9)

Some participants felt left out and not involved in university activities and research projects. Important research would include tracking research for the outcomes of rural students. Other participants, however, acknowledged the work that has been done in the area but felt that the research could better inform entry and selection of students into programs, or that tracking projects could involve rural clinicians, or that research could focus on interprofessionalism.

Implementing interprofessional education

The integration of interprofessionalism into rural programs was felt to be important and related to the national rural health interprofessional school. A year-long length of rural attachments would ideally be an interprofessional placement where students from other disciplines would learn from each other.

I think there could be an interprofessional element of that whole year, you know, the year where they’re sort of starting to think about what they might do. (P2)

The advantages of an interprofessional approach include moving away from a single discipline approach to understanding more about the strengths of other disciplines and what they can bring to the management of a patient.

GPs don’t operate in isolation, everyone else, they’re very much a part of the team, probably much more so than in urban practices. (P6)

Lack of social mission

The final theme reflected multiple critiques by participants relating to the lack of a social mission for the university. There was an overall sense that an urban-centric university is not best suited for training a rural workforce. Participants often discussed how urban academics do not understand rural life, and the blurring of boundaries that occurs between being a rural clinician and living in a rural location.

And I think because you have urban people talking about this subject and making decisions about it, they go, we want a rural GP. But they actually don’t get what that really means. If you look at [name of rural GP] but one of the things he says to some of the students is how, you need to know how I live with the people that I could do a rectal examination on, on Tuesday afternoon. (P7)

Later this participant mentioned being upset on finding out about the small number of students choosing the rural stream and thought that this reflected badly on the urban academics running the medical program.

I was just gutted out of 300 students eight students chose to go onto this rural stream option. I was disgusted 'cause what that basically means is that the academics who choose medical students, choose medical students who will not be rural people. (P7)

The university (and health governance generally) have an urban approach that fails to appreciate the specific needs of a rural population.

And what I see from an urban system looking and providing a remote rural service is that all of the decisions that are made are based on the urban need, 'cause that’s 90% of the population. So, when we sit at a governance level, the decisions that are being made are being made with the largest cohort of people in mind. (P8)

One participant framed this issue as being that the university is culturally inappropriate to be developing rural programs.

The university is culturally inappropriate when it comes to rural anything. (P7)

Discussion

The results from this study reflect the challenges faced by an urban-located university in developing rural programs and providing strategies to overcome these challenges. The strategies identified include creating rural-centric admission pathways; having rural structures in place to support rural teaching, research and curriculum development; creating longitudinal rural placements for students; and incorporating interprofessionalism into rural programs. An overarching challenge was the need for a social mission that informed and directed activity.

Our participants recognised the importance of making young rural people aware of medicine as a career option, and having preferential selection into medical school21. Evidence suggests that New Zealand medical students who are from a rural origin have a relative risk between 4.5 and 7.7 of intending to practise rurally compared to urban-origin students22. Selecting students with rural life experience, good social skills and a humanitarian outlook was also highlighted by participants. Ensuring that entry pathways adhere to social accountability principles could be one strategy for the university to implement. Social accountability is having a documented obligation to direct activities towards addressing priority health concerns of a community23.

While selection of students from a rural background was viewed as important, participants did not strongly articulate some of the challenges for rural students entering competitive health careers, such as addressing the lower educational attainment for rural students11, the limited teaching of STEM subjects in rural high schools24, the lack of university preparatory or bridging courses for rural students, and the need to have longitudinal supportive programs fostering an interest in health careers25.

Another important strategy was having rural academic structures in place. While the ideal form of rural academic structure was debatable, the key elements were that this structure needed to be rurally focused, be engaged with rural clinicians, grow rural academic capacity and develop rural research capacity. Evidence from analysis of Australian rural clinical schools, which are federally funded programs delivered by rural academics in rurally focused and located institutions, demonstrates that rural-origin students attending a rural clinical school are seven times more likely to practise rurally after specialty training compared to students who did not attend a rural clinical school and that urban-origin students are three times more likely to practise rurally26.

Some of the challenges in implanting the Australian rural clinical school model and Canadian rural clinical school models in NZ are the smaller population centres in NZ, the limited rural health investment by the NZ government, and the different rural specialities (in NZ rural specialists are almost entirely rural GPs and rural hospital doctors, compared to a wider range of generalist specialists in Australia and Canada). These differences mean that uniquely NZ solutions to rural academic structures need to be developed.

Longitudinal rural attachments and prioritising students who were genuinely interested in rural careers were seen as key by participants. This finding is consistent with the literature26. There is likely to be a place-based aspect to this finding, with some variation in the strength of the relationship between length of rural attachment and likelihood of working rurally post-graduation27-30. Place-based attributes not discussed by participants included social and cultural connections and the physical attributes of rural areas31. Ensuring that rural attachments foster social relationships within communities is likely to lead to more meaningful positive experiences for students32.

Interprofessional training was suggested as a strategy. This was mostly in the context of equipping professionals to work in multidisciplinary rural teams. The strengths of rural based interprofessional training included increased confidence in working in interprofessional settings and greater understanding of Māori culture33. However, there is little evidence that short rural interprofessional programs lead to an increase in the rural workforce34.

The findings of this study have indicated a number of core components of a rural strategy for urban-located universities. These components also include social accountability. However, the findings also suggest that universities that have historically had an urban-centric world view may struggle to operationalise their rural social mission. Although universities may have policy relating to social accountability concepts, the challenge is implementing these policies and making them visible to rural stakeholders35.

Strengths and limitations

The interviews focused specifically on weaknesses in the programs and aspects that might have been done differently. This meant that the findings appear to be generally critical of the university’s endeavours, and positive aspects were not identified or highlighted. A further limitation of this study is that inevitably the selection of participants influences the findings. However our key themes were shared by stakeholders who came from a range of backgrounds and roles. A critical approach to the analysis ensured that these disparate views were included in the findings.

Conclusion

These findings align with previous work describing rural medical education strategies for universities36,37. Some elements missing in this study were secondary school education interventions, postgraduate training, design and implementation of a rural curriculum, and community involvement in rural programs. One finding from this study not seen in other literature is the need to have an interprofessional approach. Comprehensive rural strategies have been implemented in a number of urban-located universities and have led to increases in the rural workforce38. While a number of these findings have been implemented at the University of Auckland, a clear challenge is overcoming perceptions of a lack of rural social mission when taking a pragmatic approach. Urban-located universities developing rural medical education strategies should clearly articulate and involve stakeholders in the implementation of a rural social mission in the early stages of strategy development, as well as challenge the medical focus to include interprofessionalism.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the Daniel and Olga Archibald Medical Education Research Fund.

Conflicts of interest

KE and FGS are employees of the University of Auckland and JWH is a PhD candidate at the University of Auckland.

References

Supplementary material is available on the live site https://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/8364/#supplementary