Introduction

Allied health professionals (AHPs) provide diagnostic, therapeutic, and custodial healthcare services. These services are provided by a wide variety of healthcare professionals. The definition of AHP excludes physicians, nurses, and oral health professionals1. An inequitable rural–urban distribution of AHPs impacts on not only the delivery of healthcare services, but also on the retention of rural healthcare professionals2-9. Forecast model research has assessed the supply and demand of both rural and urban allied healthcare services. These models have predicted continued increases in the gap between the number of available AHPs and the healthcare needs of the US10,11.

While recent literature has begun to look more closely at the barriers that rural AHPs face, researchers have focused their assertions and discussions on the policy and legislation surrounding these challenges11,12. These articles also focused on the current AHP workforce status within Australia, with limited inclusion of literature examining the US or other high-income countries. Although O’Sullivan and Worley11 found that there is a need for increased national level and longitudinal research regarding the AHP workforce, and Edelman et al10 offered strategies to address issues at a legislative level, it remains unclear what specific organizational, managerial, and systemic level strategies have been found to be effective for strengthening the rural AHP workforce. The existing literature has primarily been presented with a target population of high-income countries operating with universal health care. An analysis completed to support the interpretation and application of findings within the US, a high-income country operating with a mixed coverage model, would be beneficial.

Therefore, the aim of this research was to identify what literature exists related to the rural AHP workforce, answering three main questions:

- What research exists related to assessing the demographics and predicted trends of rural AHPs?

- What evidence exists pertaining to the person factors (cognitive, physical, and psychosocial) of rural AHPs?

- What studies exist related the recruitment and retention of rural AHPs?

In the preliminary literature review, it was found that the main themes examined by existing literature targeted demographics and trends regarding the AHP workforce, the person factors of rural AHPs, and the strategies targeting recruitment and retention of rural AHPs. Based on the limited research available on rural AHPs, it was determined that a scoping review would be beneficial to further research as it would allow the authors to identify key characteristics of rural AHPs, and to establish a baseline of knowledge on the available rural AHP literature13.

Methods

Protocol and registration

The protocol for this scoping review was drafted following the guidelines for reporting set forth in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR)14. The protocol was not publicly available prior to the publication of this article.

Eligibility information

Literature was excluded from this scoping review if it was not published in English. Other exclusion criteria were related to the target population. If the literature was focused on physicians, oral health professionals, or nursing, it was excluded from this scoping review as the need for more research in those professions has been well documented compared to that of AHPs, which is the target population of this scoping review15. However, studies including AHPs along with physician, oral health professionals, or nursing were included. Finally, literature was excluded if it was not conducted in relation to a rural context. Literature that was retained met the inclusion criteria for being published in the years 2011–2021, with a target population of rural allied health service providers, and answered at least one of the research questions.

Database and information sources

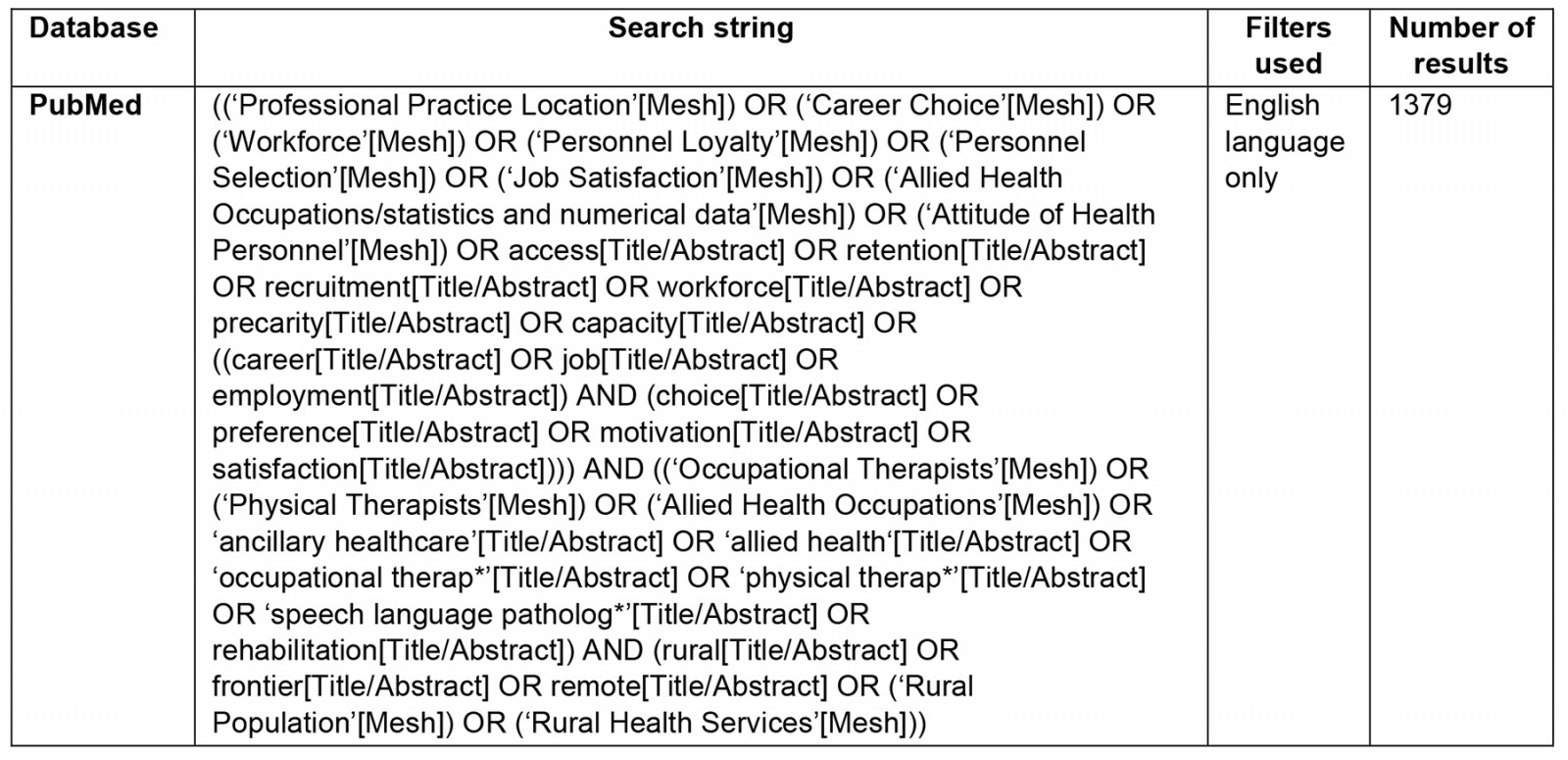

Databases included in the search were Business Source Premier (EBSCO), CINAHL (EBSCO), PubMed, and SocINDEX (EBSCO). The hand search method used a snowballing of resources from scoping and systematic reviews found in the database searches.

Searches

Database searches were completed on 3 January 2022, by a medical librarian. An example of the search strings used in the database search is included in Appendix I. The primary author completed a hand search following a snowball method on 25 February 2022.

Selection of evidence

Once database searches were completed, two researchers reviewed all abstracts to screen for inclusion in the full-text review. If there was a disagreement with the decision for inclusion or exclusion, the source in question was discussed until a convergence of views was achieved.

Data charting and items

The authors used an Excel spreadsheet to track both peer-reviewed studies and grey literature that were reviewed. Data were extracted during the full-text review by the primary author, and was then reviewed by a second researcher. Data extracted included the title, author, year, country of origin, AHPs included, purpose and research question, methodology, results, discussion and implications, and future research suggestions. The data extraction form tracked which of the three a priori categories the source was related to. If a source fell under multiple categories, the primary, secondary, or tertiary priority of those findings was determined and documented.

Critical appraisal of sources

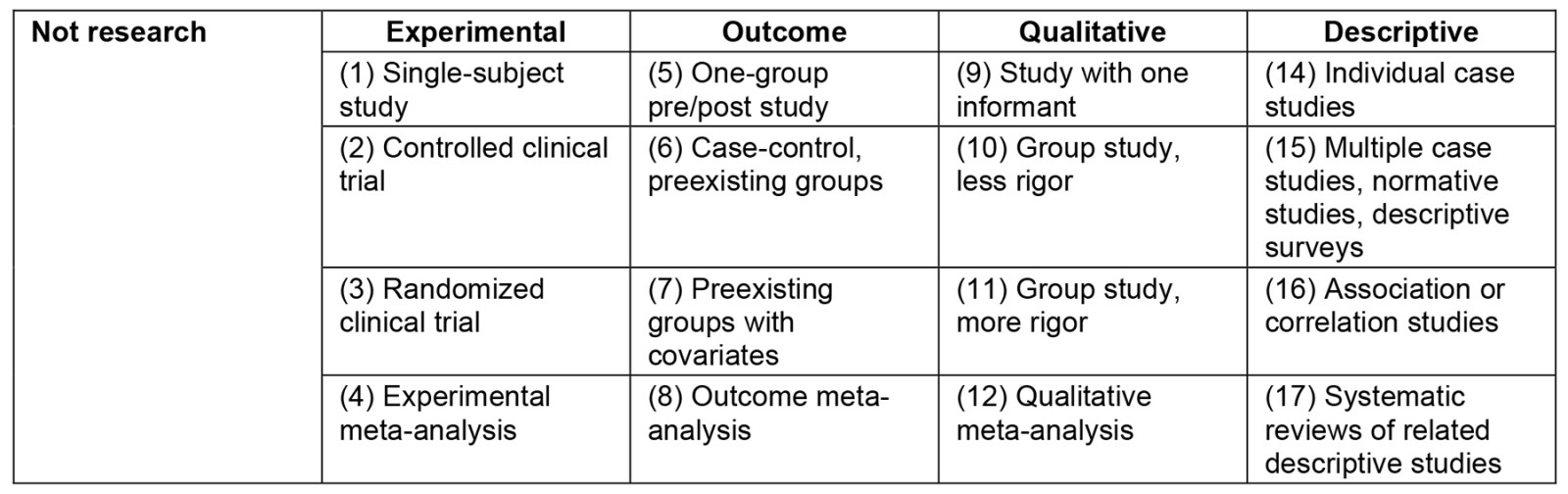

Articles were appraised according to Tomlin and Borgetto’s (2011) research pyramid mode16 (see Table 1). Sources were assessed for rigor and validity during the review, but they were determined not to be of utmost importance in relation to the findings of this article; thus, only the main categories (peer reviewed, outcomes, descriptive, qualitative, experimental, or not research) will be reported in this article.

Table 1: Levels of evidence as outlined by Tomlin and Borgetto (2011)16

Synthesis of results

The findings of the scoping review were analyzed and coded according to each of the three research questions. The three research questions assessed demographics and trends of the AHP workforce, person factors of AHPs, and recruitment and retention strategies specific to AHPs. Recruitment and retention were further analyzed into the targeted phases: prior to tertiary education, during tertiary education, postgraduate recruitment, and retention. The evidence was organized and discussed in both table and narrative formats based on the a priori categories following the linear format of education, recruitment, reasons for leaving, and retention of the AHP workforce.

Ethics approval

Institutional review board approval was not obtained because no human subjects were involved.

Results

Selection of evidence

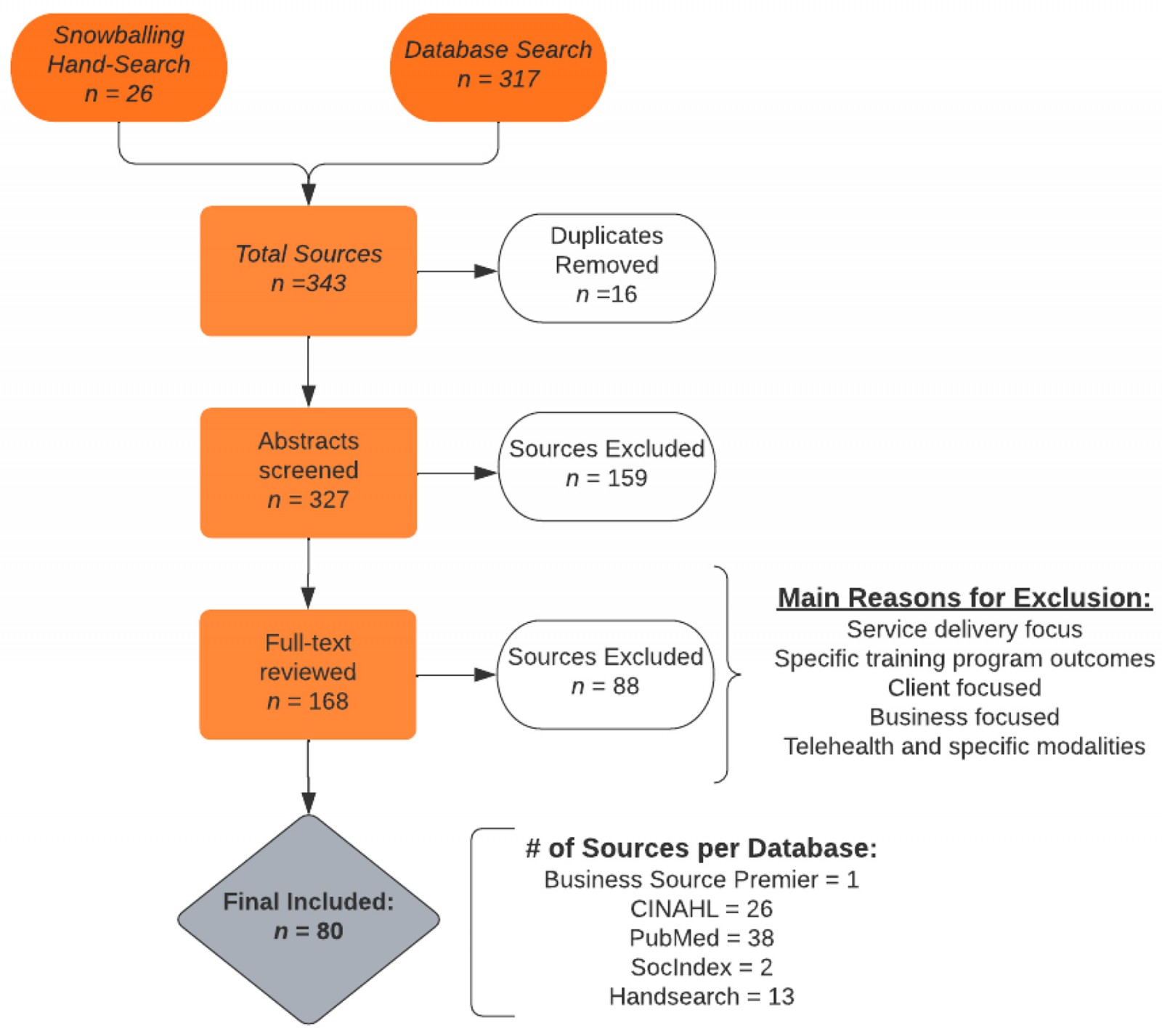

A total of 343 sources were identified between the database searches and subsequent hand search. After a full-text review, 80 articles were included in the scoping review (Fig1). Of the 80 sources, 42 were descriptive, 25 were qualitative, six were mixed methods, and seven were not research17. From the total number of articles, 77 were from peer-reviewed articles, with the remaining three providing valuable insights to the literature analysis justifying their inclusion within the review.

Figure 1: PRISMA-SCR flow chart.

Figure 1: PRISMA-SCR flow chart.

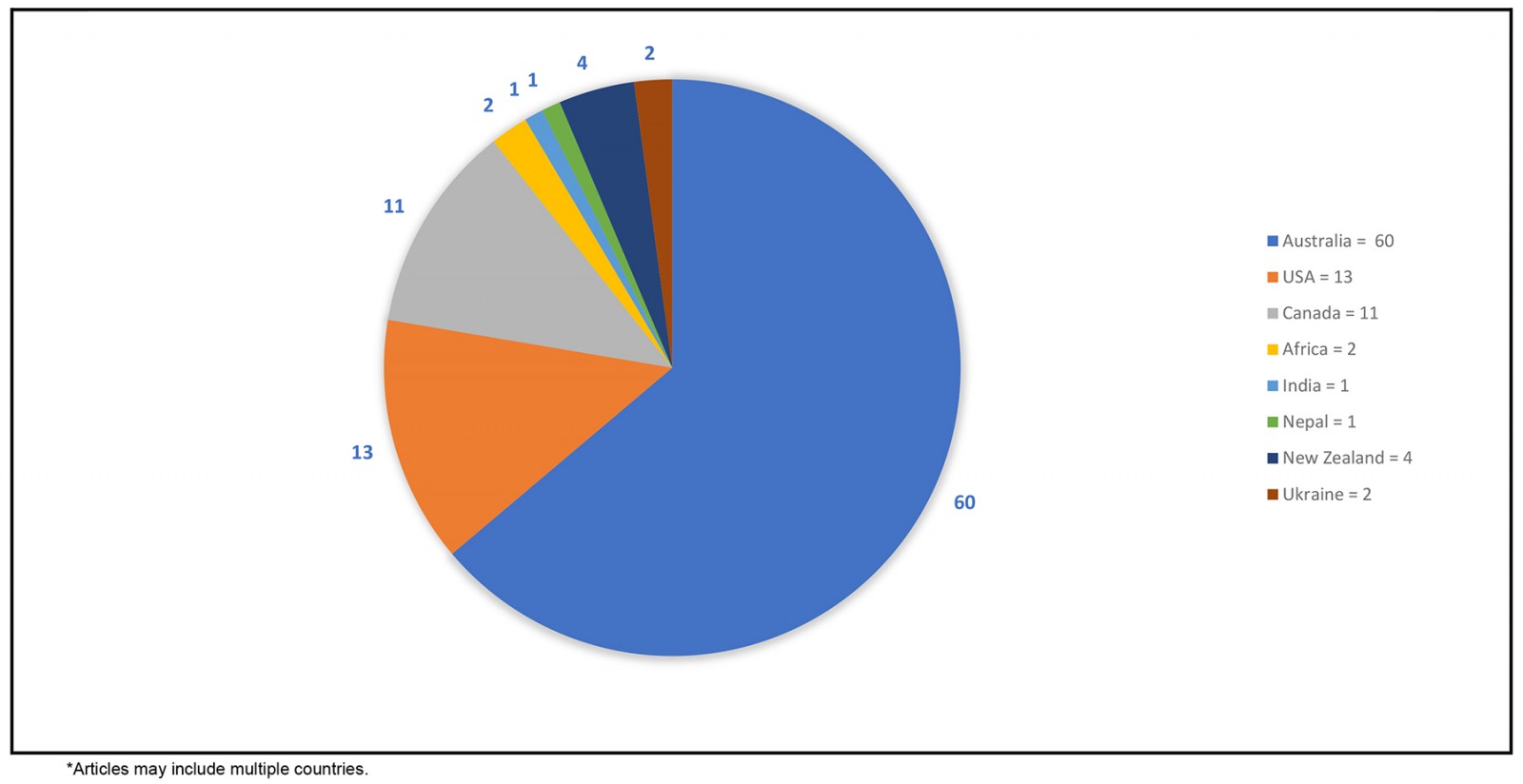

Characteristics of evidence

The evidence included came from eight countries – Australia, the US, Canada, New Zealand, Africa, Ukraine, India, and Nepal – with the frequency distributions shown in Appendix II. Twenty-three AHPs were represented in the articles, with inconsistent definitions of AHPs seen. Allied health professions included within the scoping review were speech language pathology, occupational therapy, physical therapy, audiology, chiropractic, dietetics, environmental health, exercise physiology, imagery, medical laboratory, optometrist, orthotics and prosthetics, pharmacy, psychology, social work, diversional therapy, paramedic, counselor, behavioral support, nurse’s aide, child life therapy, information management, and midwife. Fifty-six sources of evidence discussed multiple AHPs, and 25 sources only involved one AHP in their research. Professions that were examined in single-discipline studies included physical therapy, pharmacy, occupational therapy, social work, orthotics and prosthetics, and chiropractic.

Individual evidence

The literature included in the scoping review were analyzed into three a priori categories based on the initial research questions. The results of the analyses are presented below according to those categories.

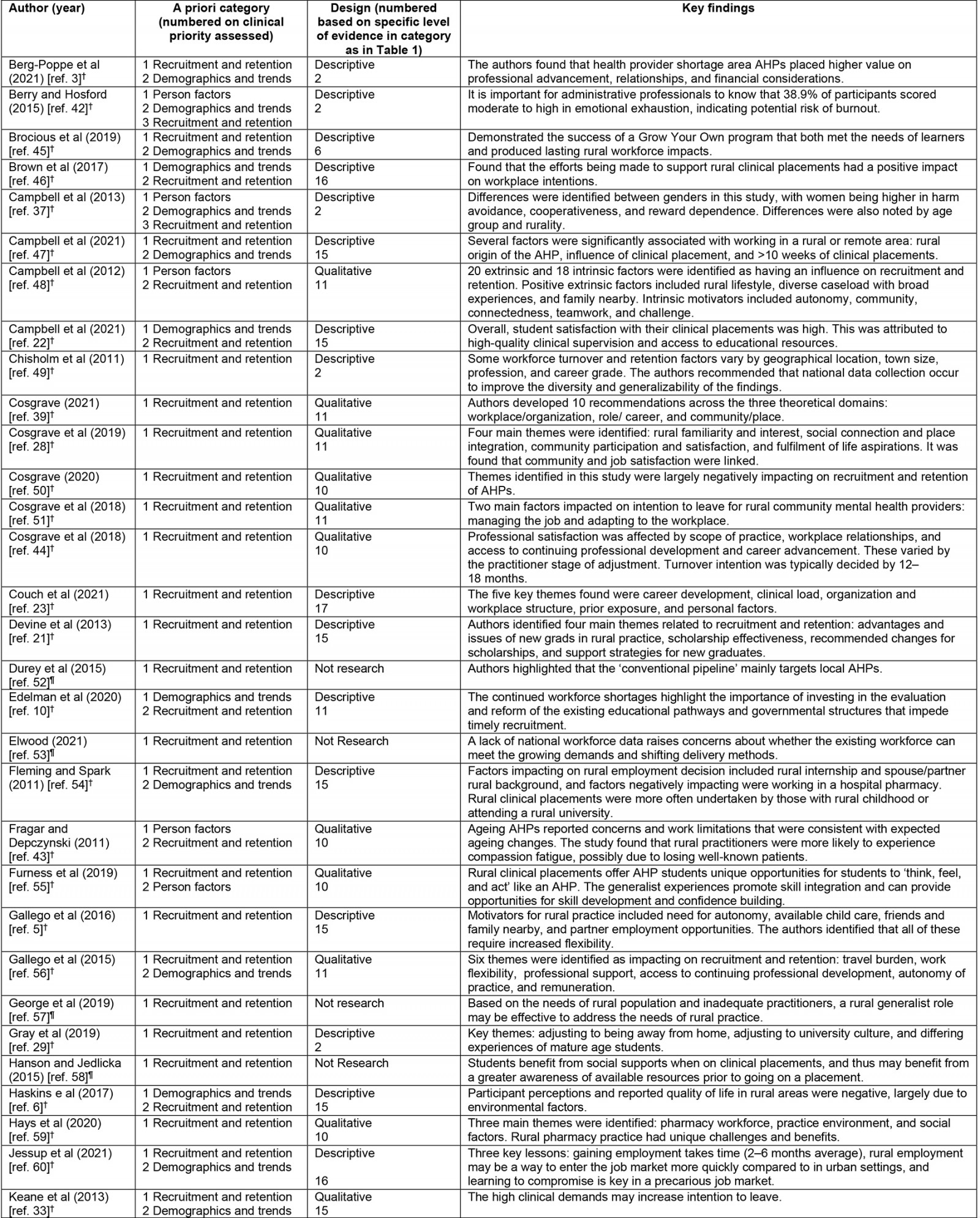

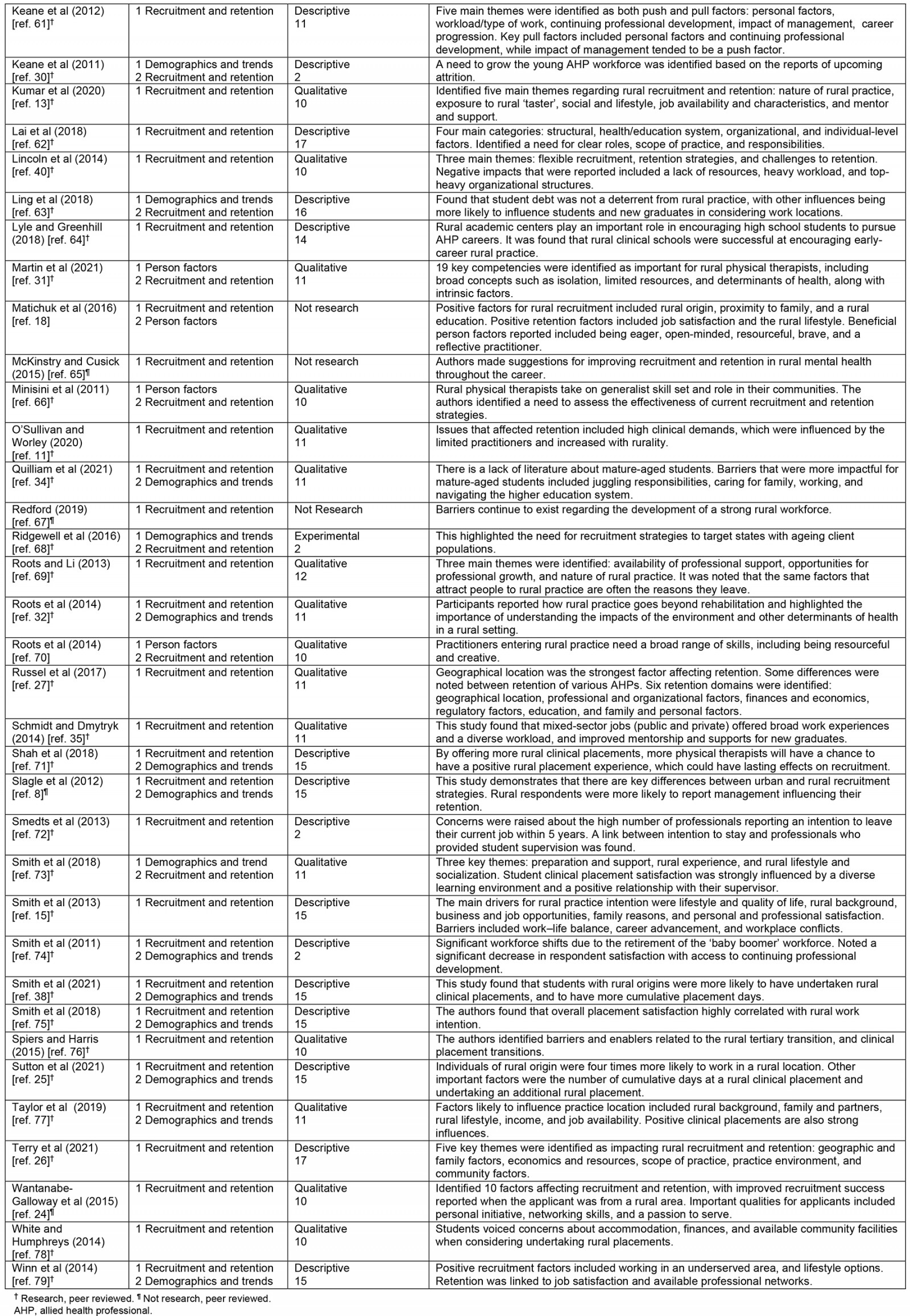

Recruitment and retention

The most frequently published research addressed recruitment and retention, with 65 articles having key findings related to this topic, as seen in Table 2. Of those 65 articles, seven focused on the stage prior to tertiary education, 34 focused on changes made during the AHP education program, 33 addressed recruitment, and 52 focused on retention of AHPs. Various strategies were suggested for each stage of the recruitment and retention process. Strategies encouraged in the literature regarding students prior to their AHP program included targeted recruitment, such as increased exposure to healthcare professions while in high school18,19 and offering quality K–12 dual enrolment programs20.

During the AHP educational program time frame, suggestions involved institutional level modifications such as offering flexible delivery methods, extending rural health pipeline programs, and increasing available scholarships and supports for students. Suggestions at the educational phase also discussed additional curricular topics that should be considered when educating and encouraging future rural health practitioners18,19,21-24. These curricular topics included population health and social determinants of health, with one source suggesting that a specialist generalist practitioner role be considered to better meet the needs of rural communities struggling with understaffing22,23. The specialist generalist role refers to the unique skills and knowledge held by rural practitioners, as they need to maintain a broad expertise for treating such a diverse caseload22. Strategies also included ways to improve clinical placements, such as thorough pre-placement briefings and orientation, allowing students opportunities to get involved in the rural community within which they are learning, and helping with finding accommodations or funding the placement25-31. Gray et al (2019)29 found that promoting student self-efficacy could reduce feelings of isolation, which are also commonly reported in rural AHPs5,23,27,29,32-44.

Table 2: Literature targeting recruitment and retention3,5,6,8,10,11,13,15,18,21-35,37-40,42-79

Demographics and trends

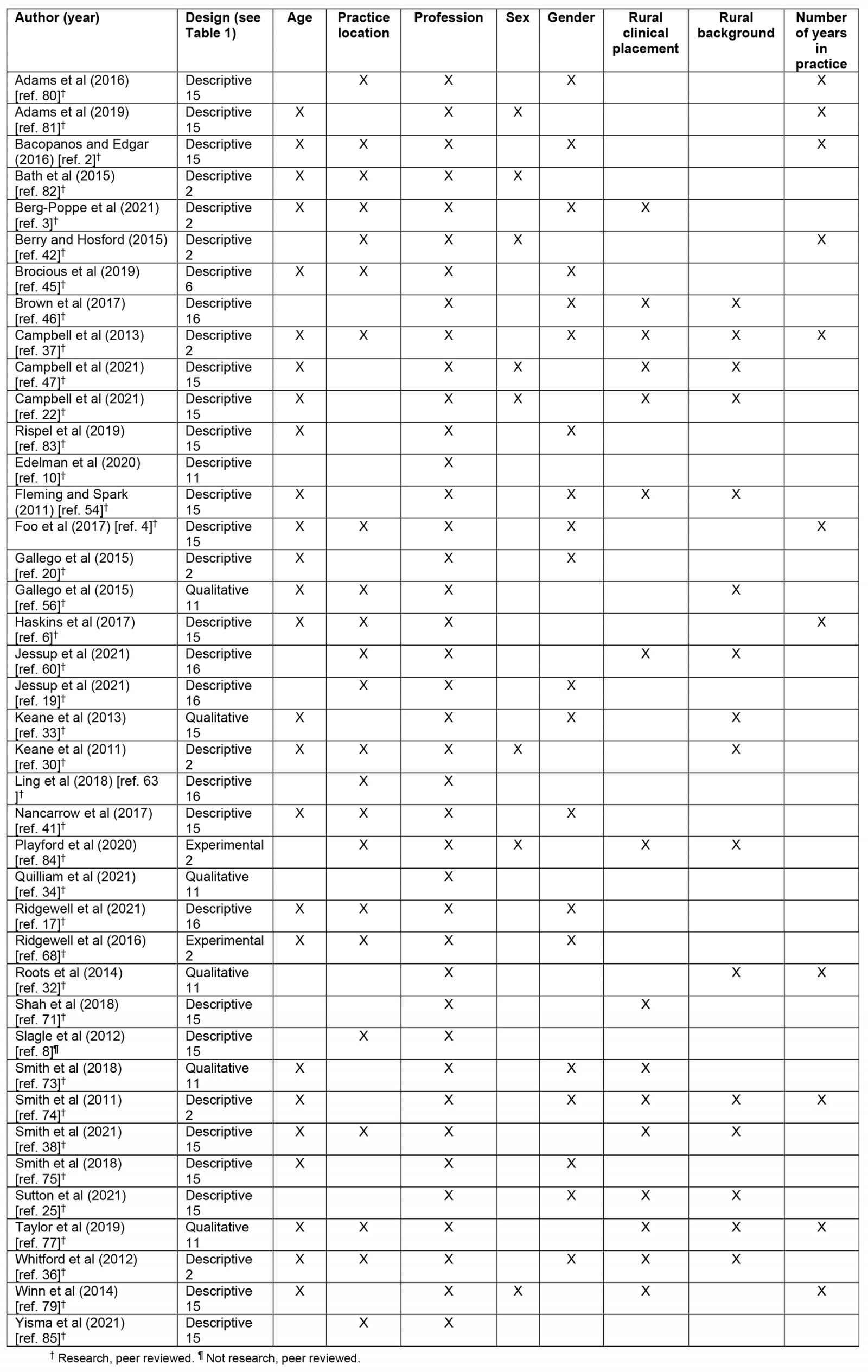

The evidence included in this study assessed a wide variety of demographics, with the most common demographics collected being age, practice location, profession, sex, gender, rural clinical placement, rural background, and number of years in practice, as displayed in Table 3. Operational definitions were not used in the data and several terms were used interchangeably, including sex and gender, and career, profession, occupation, and discipline.

While many studies included demographics in their research, sources that only addressed demographics examined factors such as: socioeconomic status and financing of one’s education, gender differences between AHPs, shifts in employment status, general environmental scans of a range of AHPs, longitudinal practice trends, AHP prevalence by region, generational differences, practice characteristic differences, and service differences influenced by practice location and practice sector40,46-53,68,74. By selecting up-to-date research, it was identified that more recent studies are no longer examining broad generational characteristics identifying workforce practitioner differences based on age. Rather, demographics were more focused on specific differences, such as the increase in female practitioners, specifically within the orthotic/prosthetic workforce or in practice sector impacts on practice, with some researchers examining the potential for inter-sector collaboration for increased practitioner supports46,50,68,69.

Table 3: Most common demographic factors assessed2-4,6,8,10,17,19,20,22,25,30,32-34,36-38,41,42,45-47,54,56,60,63,68,71,73-75,77,79-85

Person factors

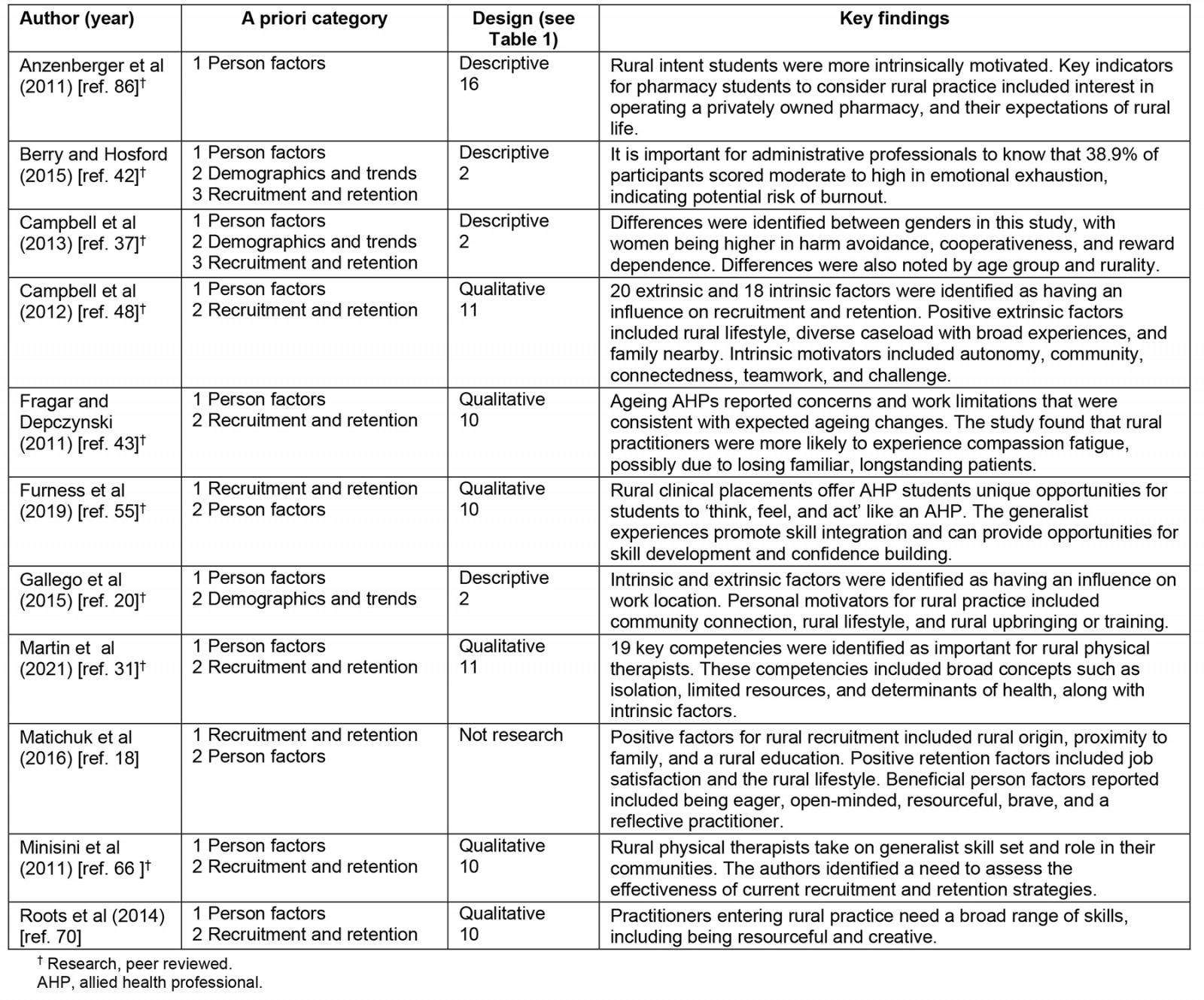

Out of the 80 pieces of evidence included in this review, only 11 addressed the person factors of rural AHPs. Most of the evidence regarding person factors was qualitative (n=6), with a mix of descriptive, mixed methods, and non-research as well17. The literature that addressed person factors is presented in Table 4.

Table 4: Literature addressing person factors18,20,31,37,42,43,48,55,66,70,86

Authors of the literature included in this scoping review have investigated cognitive, physical, and psychosocial factors that influence an individual’s decision and abilities to successfully practise in rural communities. The literature available does touch on all three of the person components, but the psychosocial domain has the most robust findings. The methods of assessing person factors varied across studies, with some having used valid and reliable assessments such as the Maslach Burnout Inventory and the Rural and Remote Allied Health Motivation and Personality survey, while other studies used focus groups to discuss personal qualities and skills that were beneficial for rural practitioners53,71.

Cognitive skills and abilities identified in the literature included managing potential ethical conflicts, understanding the needs of rural communities, using technology to support clients, and being reflective practitioners to enhance their skills21,67.

While physical skills were rarely discussed, one article focused on age-related changes that impact on more experienced therapists, including musculoskeletal changes, visual decline, increased fatigue, and decreased fine motor dexterity43. Other skills included skill integration specific to rural practice, and proactively managing one’s own health and resilience21,62.

The most discussed person factors present in the literature addressed psychosocial features. The features identified were either rural community focused or individual-level practitioner skills and traits. The community-focused traits included a desire to care for others, appreciation of feeling needed by the community, feelings of connectedness to the multidisciplinary team and surrounding community, and an enjoyment of a rural lifestyle23,33,62-66. Individual-level characteristics highlighted both positive traits and potential barriers to overcome. Positive traits for rural practitioners consisted of resourcefulness, flexibility, bravery, confidence, assertiveness, cooperation, and integrity21,23,33,67,71. Research also found that rural practitioners tended to be self-directed and novelty seeking, with lower harm avoidance than their urban counterparts21,53,71. Additionally, research identified several barriers that rural practitioners often had to overcome, such as emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, being overwhelmed, and a potential lack of community acceptance33,53,71.

Discussion

Summary of evidence

Education plays an important role in influencing AHP workforce outcomes because it fosters the development of future practitioners19,29,30,56,65. There are several ways educational programs can encourage students to consider future rural practice. Structural supports that schools can offer include flexible delivery options, established gathering spaces to support social connection, and financial supports through scholarships and grants to ease extraneous burdens that can impede student success26,32,41,56. There are also curricular topics that are beneficial for increasing a student’s understanding of the multitude of influences that affect an individual’s health. These include population health, social determinants of health, interprofessional practice, and the AHP role in mental health19,22,23. These topics are particularly relevant for rural practitioners, who probably have an extended scope of practice14,57. Educational programs should also consider and educate students as to the core competencies that practitioners identify as valuable for successful rural practice21. Core competencies identified by Martin et al (2021) included intrinsic factors such as flexibility, independence, and resourcefulness31. Lastly, rural clinical placements are beneficial for students because they allow students to experience the realities of rural practice and gain hands-on skill integration52. Immediately following rural clinical placements, students self-reported interest in future rural practice was 70–84%46,48,55,66. Time spent on clinical placements is important for students and employers to consider what skills, abilities, and person factors are most valuable for their future employment. Studies have demonstrated that person factors can be both positive and negative, depending on a wide range of extrinsic and intrinsic influences. One example of this is how a person views personal accomplishments, because it can be motivating for some practitioners, but can be a negative influence if it is absent or less valued by the practitioner33,53. Educational programs can also support this by having clear communication with their clinical placement sites in order to assess what skills and abilities the site looks for in employees, then sharing that with students so they can be prepared for the workforce21.

Recruitment of AHPs is a vital part of growing the healthcare workforce, and it benefits from the use of specific strategies to bolster the outcomes37,39,48,66. Demographic research demonstrated that while AHP workforce is growing, it continues to grow at the same rate as population growth. This means that there continues to be an inadequate AHP-to-population ratio60,70,87. It is important to consider the multitude of experiences, values, and needs of healthcare professionals when attempting to fill a job opening. The available literature discussed the importance of using targeted recruitment in order to increase exposure to rural healthcare professions when students start seriously considering their future career paths18,19. At the individual level, practitioner values and demographics should be considered to assess the fit, both introspectively by the applicant, and by the hiring team21,33,67,73,79. Any recruitment strategies used by rural clinics should be flexible and would be most beneficial if they were tailored to each applicant3,6,34,43,73. The organizational-level strategies focused on supporting new employees by offering financial and professional supports8,12,19,23,43,52,59,63,71. A key strategy to support new staff, particularly individuals with no close ties to the community in which they will be working, is to ensure that there are opportunities for the new staff to engage with the team and the surrounding community, which offers social supports and can decrease personal and professional isolation6,12,23,43.

In the time following the recruitment of an AHP, certain experiences or lack of support may increase the likelihood of that professional leaving the job. While research demonstrates that job turnover is multi-faceted, certain personal, professional, and environmental factors were reported as main influences for leaving one's job, also referred to as 'push factors'2-6. Professional push factors included a lack of career advancement opportunities, seeking better remuneration, and retirement, which vary with the sector and location of one’s employment3,6,40,45,74. Some studies found that respondents had concerns about environmental factors such as poor housing or accommodations, decreased safety, and a lack of schooling options for their children, which left rural practice with a negative connotation6,12,38,74. Push factors that were reported related to personal reasons were widespread, but included issues with management, high clinical demands, and a lack of support accessing clinical professional development24,38,43,57,61. It is necessary for communities to track the ageing client population, as they will probably need greater healthcare services57. With the subsequent increase in workload demands that place more stress on practitioners, it is important for administrative professionals to work preemptively to target recruitment, thereby mitigating risks of burnout and turnover43,53,65,75,77. While the issues identified above are important to address throughout the employment process, they are especially important to target in the first 12–18 months, as some literature found that most employees knew if they would be leaving a job within that time frame35.

Based on the knowledge of these common push factors, there have been many strategies recommended at the systemic, organization, and individual levels. The systematic level focuses on broad-scale changes that would be beneficial for AHPs, such as decreasing bureaucracy that impedes practitioners in successfully opening or maintaining private practice clinics or reducing the processes that slow down the introduction of new practitioners into the workforce52,65. One unique system-level practice model that was implemented in Australia was the public–private partnership model35. This model was beneficial because it provided both the public and private sectors with greater supports for rural practitioners, and it overcame limitations that impede rural service delivery in a traditional model38. Strategies that address the organizational level included contextual factors such as career advancement opportunities, retention incentives, and allowing flexible employment options to meet employee work–life needs2,12,18,65,75. The individual-level supports addressed the person needs by establishing mentorship and support networks, promoting the key person factors of self-efficacy, autonomy, and diversity; and increasing access to continuing professional development5,12,18,19,22,23,37,39,48,53,58,61,67,71,78,79.

Limitations

The findings of this study were limited by the set date range and the necessary restriction to English-only publications. Additionally, only snowballing hand searches were completed, despite the author identifying that citation mining hand searches would have been beneficial to broaden the research on person factors. The research questions limited the evidence that could be included, because articles that focused on service delivery and specific specialty services had to be excluded. Research findings may be skewed for certain AHP groups because there was more research related to professions such as physical therapy, occupational therapy, and social work, with less for other disciplines. Another limitation was that the emphasis on rural practice had to be clearly identified in order to be included in the scoping review, which may have inadvertently left out key research.

Future research

Research would benefit from further investigation of AHP demographics and more workforce trend predictions, with particular emphasis on examining the potential impact of practitioner life stage on attrition. While there is much research on specific recruitment and retention strategies, the evidence would be bolstered by the investigation into long-term outcomes of specific recruitment and retention strategies. Collaboration with state licensure boards would be a potential avenue for increased data collection in rural areas to provide specific and useful information to rural practitioners.

Conclusion

The evidence largely demonstrates that there is no clear road map of what leads a person to take up rural practice, but there are a multitude of common factors found among rural practitioners33,79. These factors are important for students, practitioners, and hiring managers to be aware of when considering employment in rural practice. Specific strategies used for recruitment and retention should be flexible and individualized to the needs and preferences of each practitioner. With continued staffing shortages in rural areas, it is important for practitioners and healthcare businesses to intentionally ensure that valuable time and resources are being used for training new staff appropriately, with the hope that it will lead to long-term employment.

Funding

This article was written without funding.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

appendix I:

Appendix I: Database specific search methods

Appendix II: Frequency of countries included in the literature

You might also be interested in:

2015 - Rural health activism over two decades: the Wonca Working Party on Rural Practice 1992-2012