Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer affecting women worldwide and the most common cause of cancer-related deaths1,2. The WHO Global Breast Cancer Initiative aims to reduce global breast cancer deaths by 2.5% per year and to prevent 2.5 million deaths between 2020 and 20401. Screening and early diagnosis are vital in achieving this goal1,3. A study estimated that screening every 2 years could reduce breast cancer deaths by 26% for every 1000 women tested4. For this reason, the United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends that women aged 50–74 years and at average risk of breast cancer should have mammography screening every 2 years5. In Turkey, within the scope of the National Cancer Screening Program, mammography is performed every 2 years for women aged 40–696. An effective screening program aims to reach 70% of the target population. However, studies have reported various barriers to participation in screening, and mammography screening rates are well behind the target7-9. A study conducted in Turkey reported that 35% of women have had mammography, and 75% were unaware of the need for mammography10.

Health literacy is defined as the ability of individuals to read, understand, and act on health information11. For this reason, it has been previously emphasized that health literacy is a crucial component in predicting women’s behaviors, including knowledge, awareness, and decision-making for cancer screening12-14, and a high level of health literacy is one of the crucial determinants of participation in cancer screenings13,15-17. In addition, individuals with poor health literacy are less able to understand and evaluate the benefits of mammography screening and have lower participation rates12,18. Therefore, effective interventions should be developed for individuals with insufficient health literacy to increase screening rates. To develop an effective intervention, it is important to carry out studies that reveal the current situation. Although there are international studies investigating the relationship between breast cancer behaviors and health literacy12,13,15,19, the number of studies dealing with the issue, especially in rural areas in Turkey, is limited. Considering that women living in rural areas have lower rates of accessing and benefiting from health services20, it is essential to investigate the issue among women living in rural areas. This study aims to determine the relationship between breast cancer screening behaviors and health literacy levels.

Methods

Design and participants

The population of the cross-sectional study consisted of women aged 40–69 living in a town in the south of Turkey. The study was completed with 312 individuals who could read and write in Turkish, had cognitive competence, could answer the questions, and volunteered to participate in the research. Whether the sample size was sufficient for the research hypothesis at the 95% confidence level was calculated using GPower v3.1.9.2 (https://www.psychologie.hhu.de/arbeitsgruppen/allgemeine-psychologie-und-arbeitspsychologie/gpower) after the data collection phase. According to the post-hoc power calculated over the between-groups relationships, the study’s power was 99%, with an alpha of 0.05 and an effect size of 0.712.

Data collection

Data were collected between October and December 2022, via a survey form, from women who applied to the health house center in a rural area for various reasons. Convenience sampling was used to determine the women to be included in the sample. The questionnaire consisted of three parts: questions to define the individual (12 questions), questions about breast cancer screening (13 questions), and the Turkish Health Literacy Scale-32 (THLS-32).

Turkish Health Literacy Scale-32: The scale was developed by the European Health Literacy Research Consortium. Its validity and reliability in Turkey was evaluated by Okyay et al21. The scale consists of 32 questions, including two health-related dimensions (treatment and service, prevention of diseases and health promotion) and four information-acquisition processes (access, understanding, evaluation, and use/application) concerning health-related decision-making and practices. According to the scores obtained from the scale, 0–25 points indicate insufficient health literacy, 25–33 points problematic/limited health literacy, 33–42 points adequate health literacy, and 42–50 perfect health literacy. In this study, the overall reliability of the scale was calculated as 0.973.

Variables

The study’s dependent variable was participation in mammography screening in the last 2 years. Sociodemographic characteristics, some characteristics related to lifestyle, characteristics related to disease/health status, and THLS-32 levels were used as independent variables.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences v25.0 (IBM Corp; https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics). Descriptive statistical methods (number, percentage, mean, and standard deviation) were used to evaluate the data. The fit for normal distribution was checked with kurtosis and skewness values. The scale scores met the assumption of normal distribution. For this reason, the independent sample t-test and Mann–Whitney U-test were used to compare quantitative data. In addition, the relationship between having mammography in the last 2 years and health literacy status was examined by χ2 analysis. Furthermore, the individuals who had a value above the cut-off score for health literacy who had breast mammography in the last 2 years were determined.

Ethics approval

Approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University (2022-YÖNP-0641; 16/33). In addition, consent was taken from the participants through an informed consent form describing the study content.

Results

Participants

The mean age of the participants was 54.0±8.6 years, and 64.1% defined their income as in balance with their expenses. Slightly more than half (51.0%) of the participants were primary school graduates, and one-third (30.4%) were not working. About one-third of the participants smoked (27.9%), but none used alcohol, and their physical activity rates were low (20.8%). Of the participants, 14.4% had a breast-related disease and 10.6% had lost a relative to breast cancer. In addition, 97.4% had heard of at least one breast cancer screening, 93.6% had heard of mammography, and 28.5% had had mammography in the last 2 years.

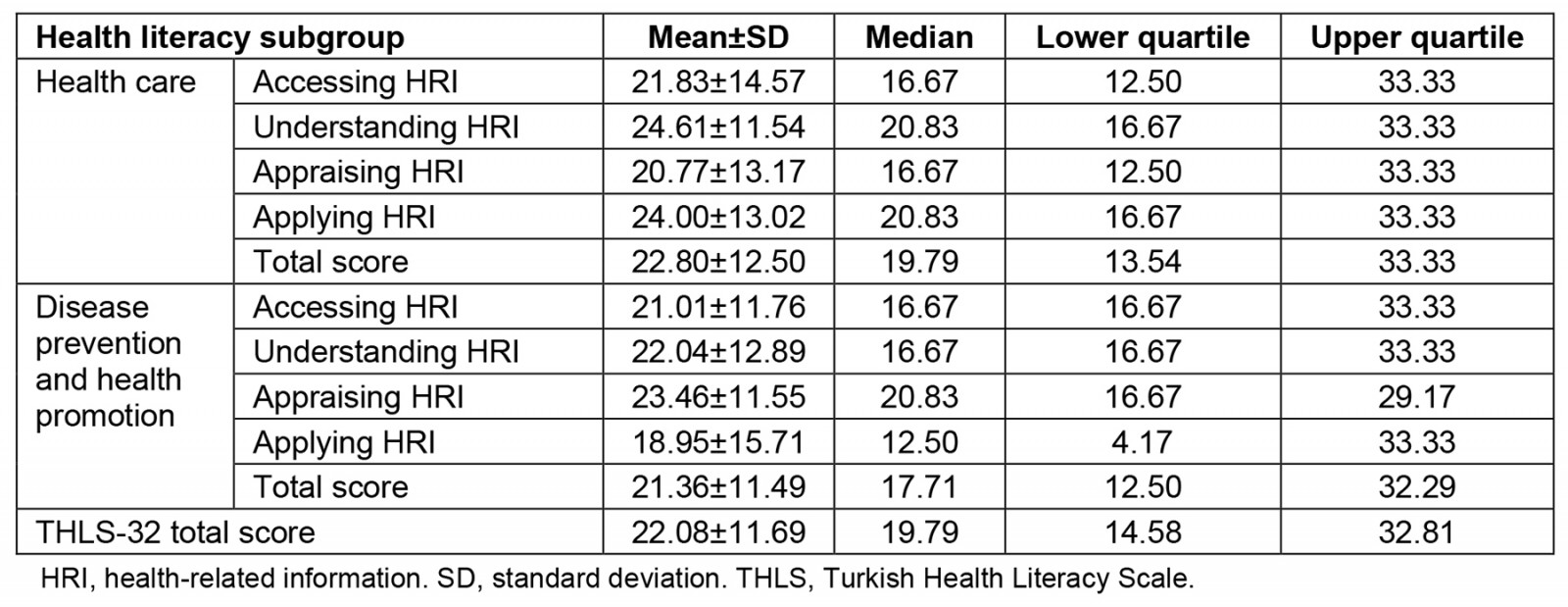

Distribution of the results of the THLS-32

The distribution of the scores obtained by the participants from the THLS-32 scale is given in Table 1. The health literacy levels of the participants was insufficient.

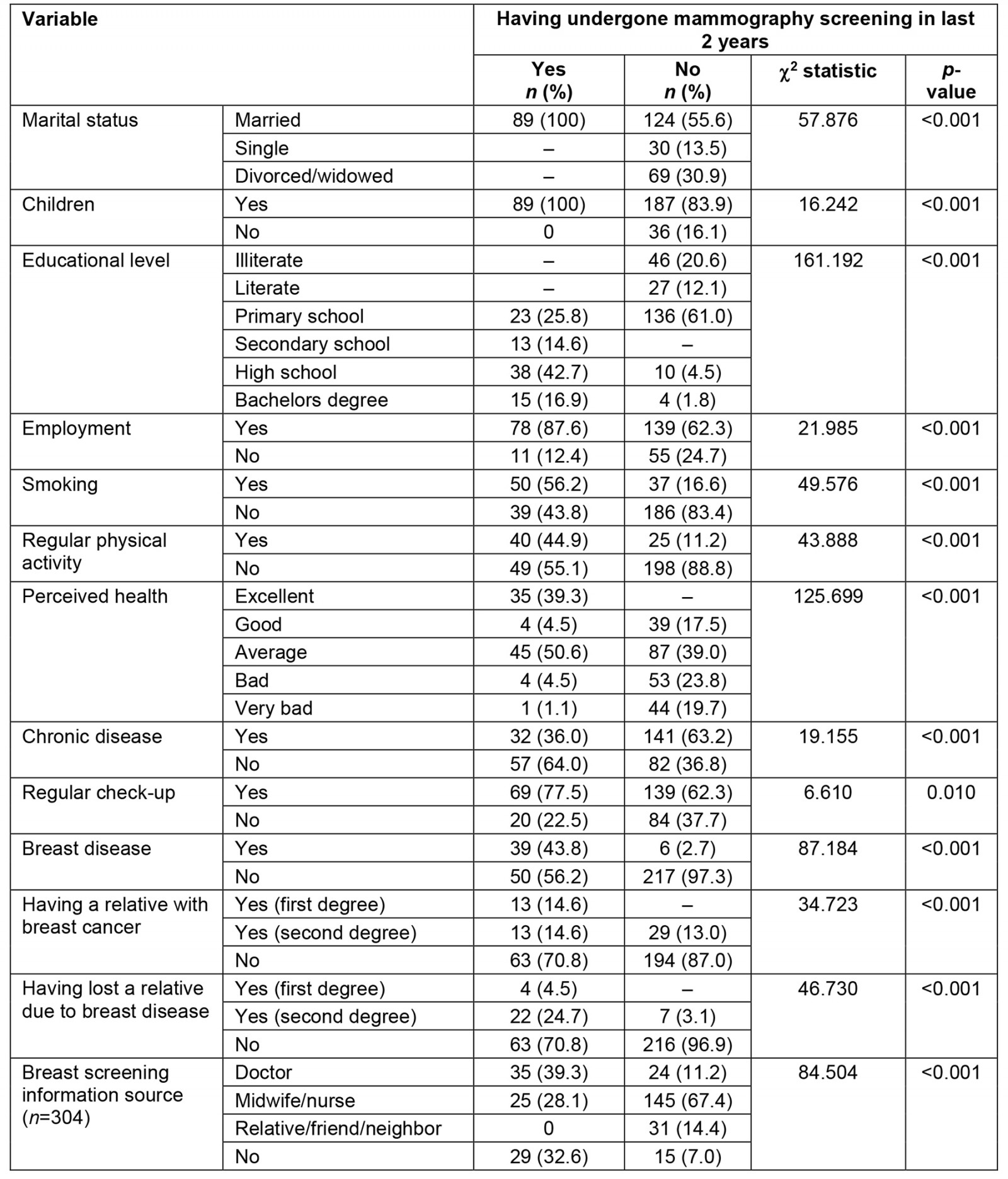

The relationships of the studied variables with mammogram screening are given in Table 2.

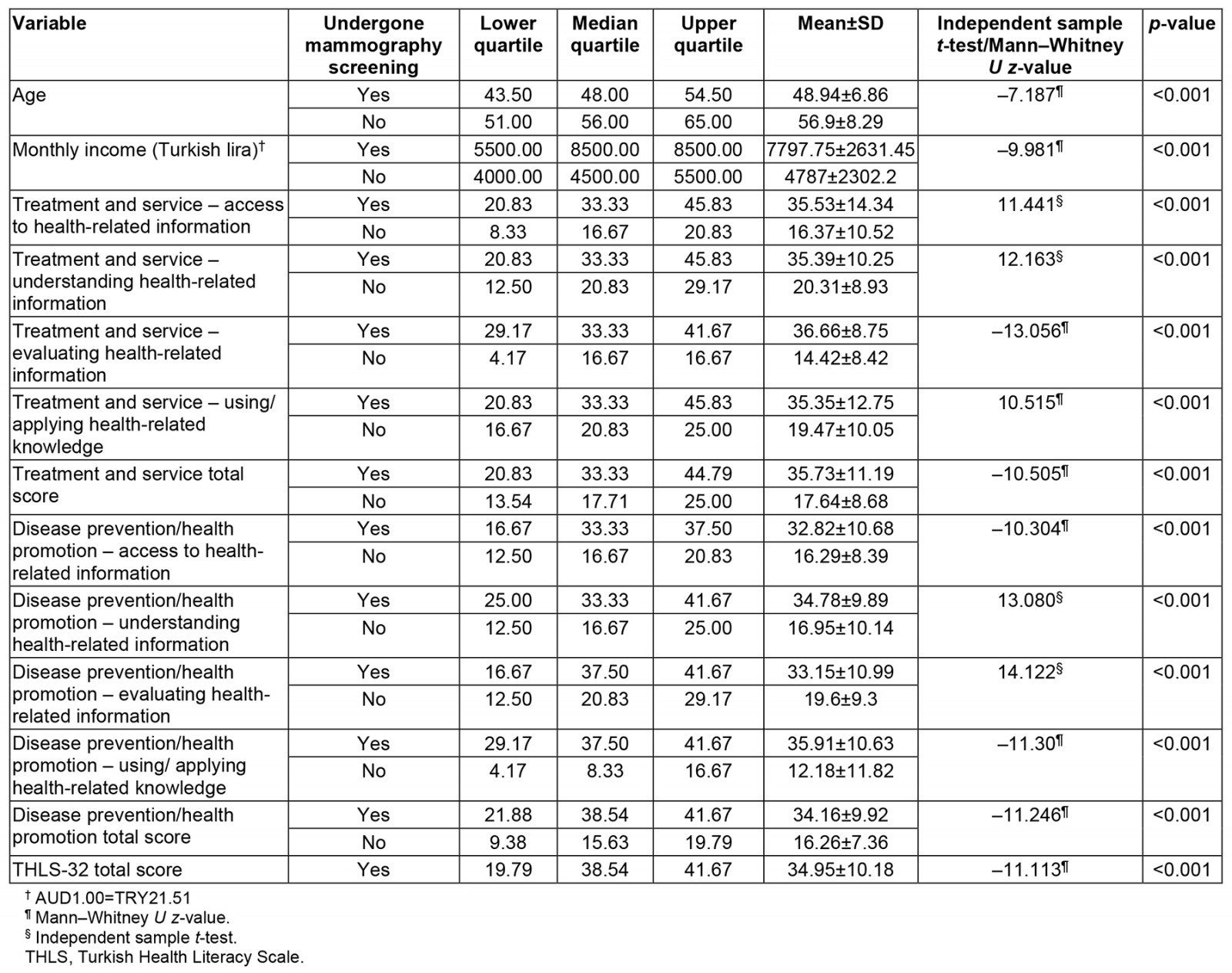

There were significant differences between the mammogram screening groups concerning most THLS-32 subgroup scores, including the THLS-32 total score (Table 3).

In the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, the cut-off score was 33.59. A sensitivity of 0.640, specificity of 0.045, and likelihood ratio of 14.28 were obtained. The area under the ROC curve was significant (area=0.902 p=0.000). The results determined that individuals with a health literacy score of 33.59 and above had breast mammography in the last two years. This result supports the assumption that those who score 33–42 on THLS-32 on the scale have sufficient health literacy.

Table 1: Distribution of the THLS-32 total and subgroup scores

Table 2: Relationships of the studied variables with mammography screening

Table 3: Comparison of the numerical variables between the mammography screening groups

Discussion

Although breast cancers (the most common cancer types affecting women worldwide) have the chance of being detected at an early stage by screening, the results of this study and of other studies show that breast cancer screening rates are far behind the target14,22. For this reason, implementing interventions that aim to increase women’s health literacy levels have been included in the literature23-26. These interventions include mass media (eg television, radio, and billboards), small media (eg videos), printed materials (eg brochures, flyers, letters, and newsletters), group training, and patient reminders23. In addition, multiple interventions, including email, phone calls, and home visits, have been reported to be effective in increasing mammography screening rates26. The inclusion of community health workers in screening programs is also among the effective interventions23. Furthermore, in this study and other studies, healthcare professionals were among the top information sources for breast cancer screening programs10,27. However, a study emphasized that the knowledge level of breast cancer among health professionals working in primary care screening is insufficient22,28. For this reason, it is important to increase the awareness of health professionals working in primary care, especially serving the society in rural areas, in order to increase the participation of individuals in cancer screening.

This study showed a statistically significant relationship between some sociodemographic characteristics of the women and the presence of breast-related disease, having a relative with breast cancer, having a relative lost to breast cancer, the source of information about breast cancer screening, and having mammography in the last 2 years. Similarly, in other studies, the presence of breast-related disease17 and having a relative with breast cancer17,29 are associated with having mammography screening.

The total score obtained from the THLS-32 scale in this study showed that the health literacy levels of the participants need to be increased. These results are consistent with those observed in previous studies17,19,29. Studies show that individuals with low health literacy levels have lower levels of knowledge and awareness about cancer screening than those with adequate literacy levels15. As a result of this study, there were significant differences between health literacy levels and having mammography in the last 2 years. Similarly, studies have emphasized the relationship between health literacy and participation in mammography screenings12,17-19,29. However, insufficient health literacy levels of women in this study may have caused the low screening rates. For this reason, implementing interventions that aim to increase women’s SDL levels in screening programs may increase participation in screening programs30. Health education is one of the most effective strategies for improving health literacy in society31. Therefore, breast cancer education programs and public health campaigns should be organized according to the health literacy level of women14. Also, it has been stated that visual aids in culturally appropriate health education materials may benefit people with low literacy levels32.

The strengths of this study are that it is one of the limited studies examining the relationship between health literacy and mammography screenings of rural women in Turkey. However, the relatively small sample size, the use of the non-probability sampling method, and the fact that the research was conducted in a single district are among the limitations of this study. For this reason, multicenter studies should be conducted with larger sample groups.

Conclusion

The results of this study showed that women's breast cancer screening rates were well behind the target and were associated with regular check-ups, a history of breast disease and cancer, and breast cancer information sources regarding breast cancer screenings. In addition, the health literacy levels of the participants were insufficient, and there was a significant relationship between their participation in breast cancer screenings. For this reason, effective intervention studies aiming to increase the health literacy levels of society may contribute to the increase in breast cancer screenings. In particular, community health workers are in an ideal position to implement these intervention programs.

Funding

No funding was provided for this study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

You might also be interested in:

2015 - Indonesian medical students' preferences associated with the intention toward rural practice