Introduction

Health care has been recognized as a fundamental human right, yet many rural areas struggle with accessing highly skilled physicians1-3. In both Canada and Australia, rural residents have a greater risk of circulatory disease, suicide, and all-cause mortality4. Improving the number of primary care physicians may help reduce the disease burden in rural areas as work by Shi (1992, 1994) found that US states with higher ratios of primary care physicians to population had better health outcomes5,6. Globally, numerous programs, policies, and practices have been developed and implemented to attempt to reduce the maldistribution of primary care physicians. Yet, the problem of retaining rural physicians persist7,8.

Undergraduate medical education interventions have been identified as potential approaches for increasing the number of primary care physicians who practice in rural and remote communities9-11. Some of these strategies have included rural student recruitment, rural-orientated admissions policies and medical curriculum, and rural-based practice learning experiences8,9. Among these, rural placements have received a considerable amount of research attention12.

The Northern Ontario School of Medicine University (NOSM U) was founded with a social accountability mandate to address rural physician shortages in Northern Ontario. NOSM U aims to accomplish its mandate through the recruitment of undergraduate medical students who have an interest in rural practice and providing these students with positive rural educational experiences in both their undergraduate and postgraduate medical education13. In its undergraduate curriculum, NOSM U employs a decentralized educational model embedded with experiential learning components, where students undertake several placements in rural and remote communities. In their first year, students participate in a 4-week placement in Indigenous communities; in second year, students participate in two 4-week rural placements; and in third year they complete an 8-month comprehensive community longitudinal clerkship14-16.

The two 4-week remote and rural community placements in second year (henceforth referred to as RRCPs) are where students experience life as a rural physician17. The purpose of these placements is to ‘learn about what it is like to live and practice medicine in these (rural and remote) settings’18. In these experiences, learners are instructed to spend 20 hours in clinical time with their preceptor each week. Additionally, they spend 3 hours in community learning sessions, and learners are encouraged to participate in community events or activities. During this time students also participate in the formal curriculum, which is delivered using pre-recorded lectures or technology-enabled small-group sessions18. As their first exposure to rural clinical practice, RRCPs play an important role in framing student perception of rural health care. However, not all placements are created equally, and research conducted in Australia has suggested that students who were satisfied with their rural placement were more than two times more likely to have the intention to pursue rural or remote practice19. Therefore, it behooves researchers and medical school administrators to explore RRCPs at NOSM U and determine what factors create positive rural placement experiences.

Previous research on rural placements from other institutions have examined students’ perceptions of rural placements and described both the positive and negative impacts of these experiences on their future practice intentions20. Some students felt they had gained well-rounded clinical skills, problem-solving skills, increased capacity to deal with undifferentiated patients, and increased confidence and self-esteem as an emerging medical practitioner20. On the other hand, some students described the negatives of rural placements, including difficulty with ‘bumping’ into patients outside of the clinic, not meeting learning objectives, and anxieties associated with rural living20. Many of these positive and negative experiences can be mitigated or amplified by a student’s preceptor in the rural community21. Misalignment between a student’s and preceptor’s expectations of rural placements may lead to a negative experience and decrease the likelihood of future rural practice. A study by Ross and colleagues investigated the experiences of preceptors and students involved in rural community placements, but they combined both preceptor and student views into their analysis. This approach has led to some interesting findings, including what motivated preceptors to take on learners, the challenges with communication between the university and the preceptor, and the value of place in medical education22. However, it is imperative that the viewpoints of students and faculty are separated as each group may have different expectations or perceptions of what creates a positive experience. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to explore what rural preceptors believe contributes to positive early rural placements for students. With positive rural placements being cited as an important factor in medical students’ career intentions and preceptors having a major influence on the quality of these placements, it is essential to understand their view of positive placements.

Methods

This study takes a pragmatic approach to answering the research question. The research project had two distinct phases. First, participants were recruited through purposive sampling: preceptors that had been a primary preceptor in the last 2 years were invited to participate. In-depth individual interviews were conducted with these participants, and thematically analyzed. Second, these results from the in-depth interviews were used to create closed-ended survey questions. Again, a purposive sampling strategy was used, and email invitations were sent to all preceptors who had taken on a student. These results were analysed using frequencies (percentages). Participants were recruited through the NOSM U undergraduate medical education office. This sequential approach was selected because it allows researchers to explore an area of interest – in this case, positive rural placement – and then measure these variables quantitatively in a larger sample. This approach is more flexible because it is not tied to a specific research paradigm and helps give more robust evidence through the combination of the explanation in qualitative data and the agreement or disagreement in the quantitative data. Demographic data were not collected, to reduce the chance of identification.

Phase 1: In-depth interviews

In total, five preceptors agreed to participate in the in-depth interviews. A semi-structured interview lasting 30–60 minutes was conducted with these participants. The guide was based on a literature review on positive rural placements with questions posed pertaining to the role of placements: how they affect student knowledge, skills, and abilities; challenges and benefits for students and community; and duration, location, and timing of placements23. The interviews were transcribed verbatim. Participants were given pseudonyms, and all identifying information was removed. The transcripts were then sent to participants to be validated, and all participants agreed that the transcripts were accurate.

Phase 2: Surveys

Based on the results from the interviews and a literature review on positive rural placements, a survey was created to further understand aspects of effective rural placements. The survey consisted of three closed-ended questions in which participants were asked to rank their top three responses (see Appendix I for full list of questions). In tables 1–3 the closed-ended questions and possible responses are listed. The survey was piloted with a group of preceptors to ensure clarity and content validity. In total, 15 preceptors filled out an anonymous survey; 14 of them had taken on a student in the previous 2 years.

Analysis

Phase 1: In-depth interviews: All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and uploaded to Atlas.ti v8.4.24 (https://atlasti.com). Initially, a thematic analysis was conducted in which two researchers (HS and BB) immersed themselves in the data by doing multiple close readings, and developed codes in-text based on specific words or phrases24. These words and phrases were then combined into themes and reviewed by two members of the research team (KT and EC). Finally, the larger team (BR and FK) helped provide critical feedback. The research team consisted of an interdisciplinary group with backgrounds in medicine, pedagogy, and human resources. The team included a mix of males and females, and rural- and urban-dwelling individuals. The results are interpreted based on each individual’s unique experience and were discussed until an agreement of the interpretation was formed. Researchers maintained rigor by purposive sampling, multiple researchers confirming findings, member checking and multiple tools being used to confirm findings25.

Phase 2: Surveys: Response percentages were calculated in Qualtrics. Because the purpose of phase 2 was to verify information from more sources and test consistency through different instruments, both the interview and survey results are presented together in the results section. The results section is presented with the name of the theme and quotes from the interview, and each section ends with the addition of the results from the survey.

Ethics approval

This study received ethics approval from the Lakehead University research ethics boards (file number 1466625) and was done in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Participants from the interview and survey were informed and gave consent to having data used for publication purposes, with all personal identifiers being stripped and pseudonyms being used.

Results

Themes – role, risk, and reciprocity

In studying what rural preceptors believe contributes to positive early rural placements for students, the research team identified three overarching themes from the interview and survey data. First, the preceptors articulated how important the role of RRCPs are in a student’s medical journey. Second, the preceptors identified the inherent risks of rural placements. Third, the preceptors highlighted the need for reciprocity between stakeholders to create positive learning environments. Each of these themes are further articulated in the following sections.

Role of placements – a bridge between books and care

For students’ first clinical experience in the NOSM U curriculum, preceptors identified how RRCPs play a transitionary role in the integration of pre-clinical formal learning into clinical settings and are important for sparking interest in rural practice and providing an understanding of comprehensive care. Preceptor Felix framed the role of the placement in the following way:

It’s a transition period, an important one, we spend one or two years priming most of medicine into their brains in a more of a didactic way and then they emerge into the clinical world and have to start dealing with actual patients. I find it’s usually a bit overwhelming for them so I find the role of this is to my hope is to integrate their basic science knowledge that they’ve just acquired into the new clinical role.

This sentiment was echoed by other preceptors. Annabelle commented that:

… it allows an early integration of the knowledge, where learners are used to, up until this point, doing a lot of [organ] systems-based learning. Here they have the chance to begin to combine that systems-based learning with clinical care into integrated learning while in a rural environment.

The significance of this clinical learning occurring in a rural setting was emphasized multiple times by other preceptors in the study. Participants stated that it is important for students to interact with 'the patient within their setting' in order to understand how the realities of rural practice differ from those of urban centres. As Annabelle explained:

We also value the opportunity for learners to see their patients in multiple settings, so they might see them as an inpatient and later on [in the office or] at a patient’s home, and they may also see them working at the hardware store or the grocery store. So recognizing patients within community is part of the experience.

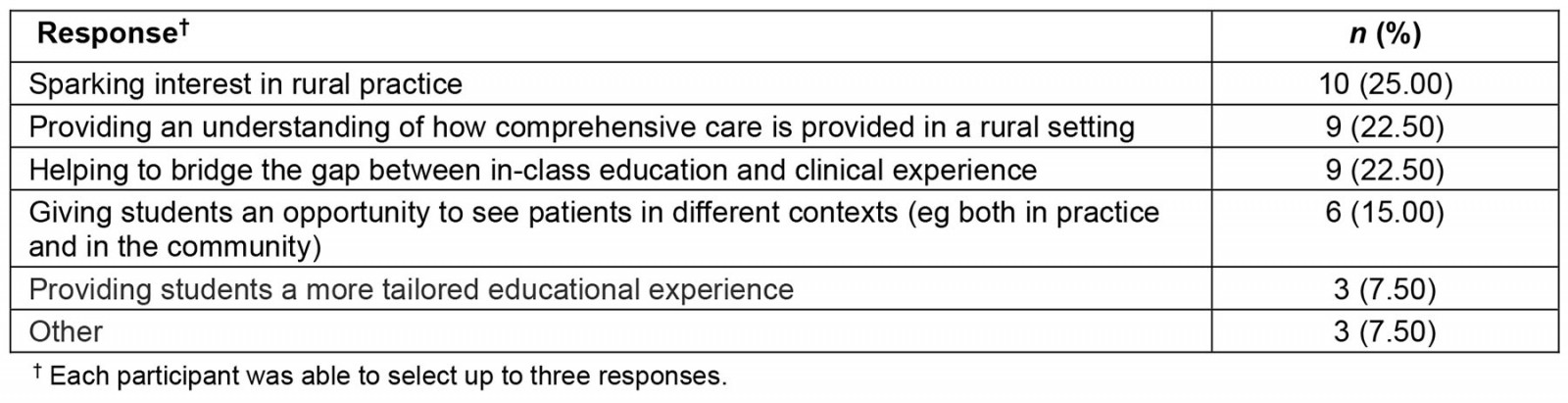

The survey results underlined the purpose of the placement. Preceptors responded that sparking interest, providing, and understanding comprehensive care, and helping to bridge the gap between in-class education and clinical experience were the aims of early rural placements (Table 1).

Table 1: Aims of early rural placement in undergraduate medicine – preceptor responses

Risk of rural placements – ‘It’s a double-edged sword’

Preceptors all noted that there is a risk to rural placements. Examples provided by the preceptors were that some students may learn that they are not happy living in rural areas and that students may not like the assigned rural practice or preceptor. The risk is not just for students, as participants in the study highlighted the extra workload of taking RRCP students and how this could place rural preceptors at further risk of burnout.

Preceptors shared how students who are from urban areas are sometimes uncomfortable with the lack of privacy that living in a small community affords. For example, Maggie said:

Also the lack of privacy can be a two-way street. Sometimes its intimidating to people who aren’t used to being under a microscope coming into a small town. Sometimes it can be more of their personal lives examined than they would like so it’s a double-edged sword – it’s very interesting.

It was noted by some of the preceptors that these placements have the potential to make it clear for students whether they are well suited for rural practice. Felix recounted a story of how the placement elucidated how one of his students was not well suited to rural generalism, but the experience did give the student the opportunity to learn about how family medicine works behind the scenes. Annabelle commented that the placement is an opportunity for the preceptors to model clinical courage, which is performing a procedure that you may have only done once or twice but doing it because it is in the best interest of the patient and for the student to consider whether they are well suited to this type of practice.

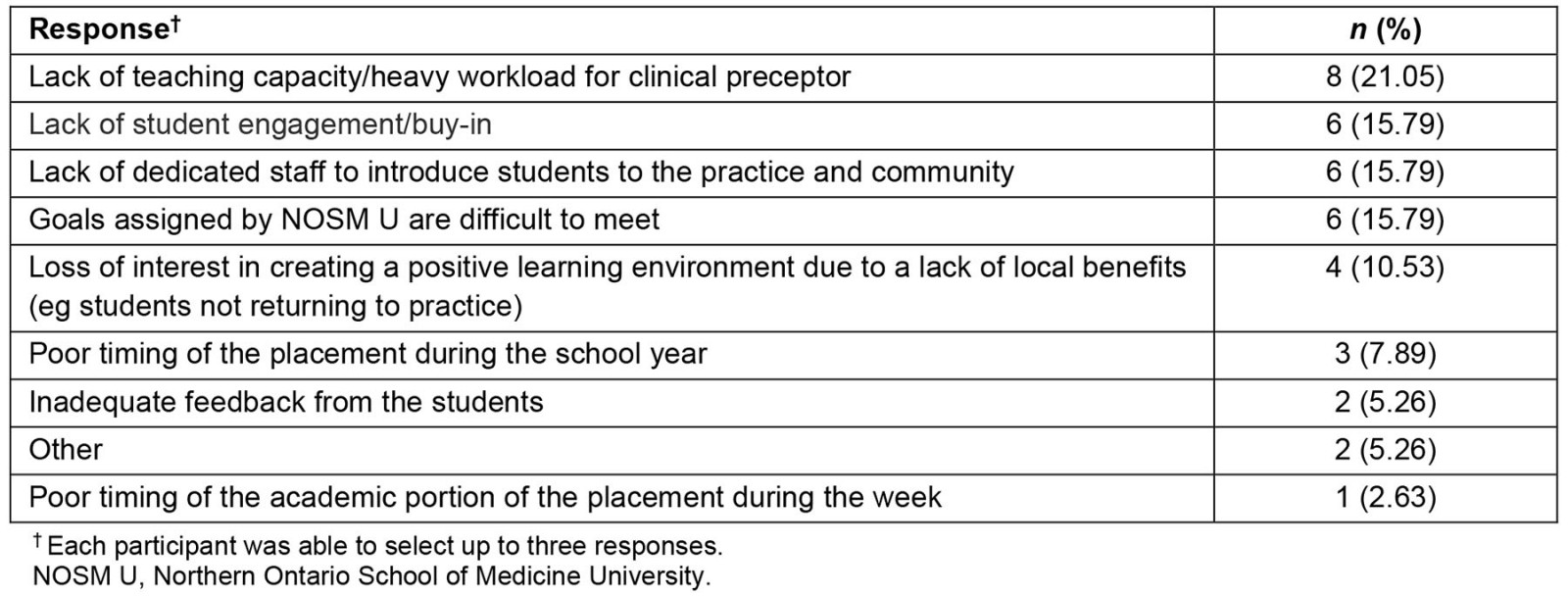

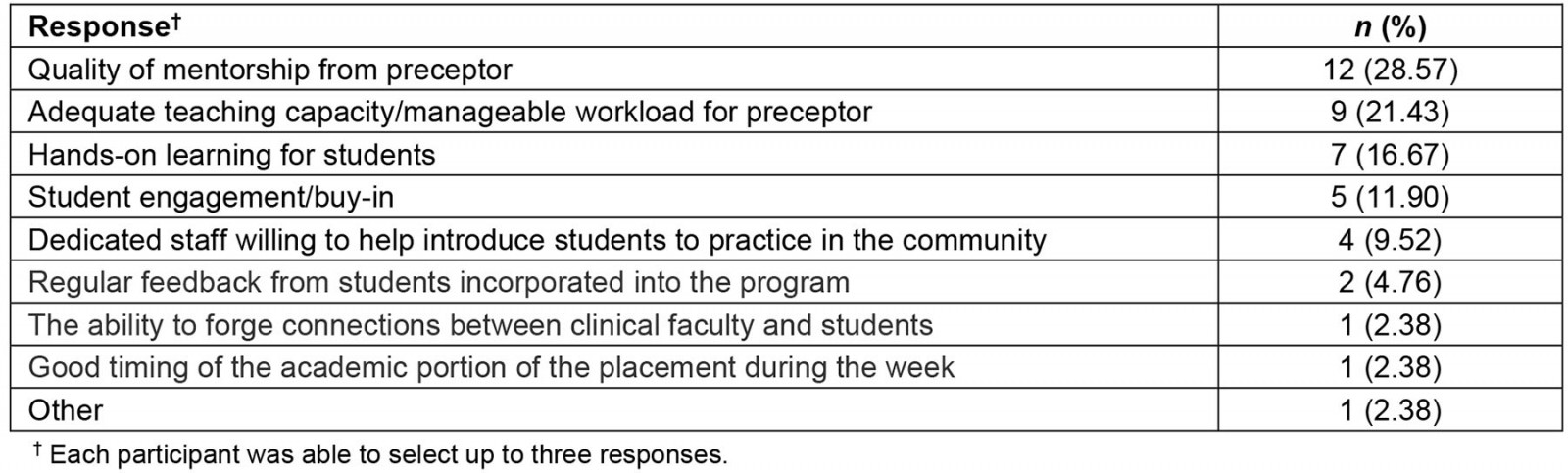

These placements may also place preceptors at risk as it was noted that, in particularly underserviced communities, it can be difficult for preceptors to dedicate sufficient time to work with students. Anne suggested that to ensure that preceptors have the capacity to take on students, the government needs to be involved in reviewing the number of preceptors required for a community to assume an academic mandate. The survey confirmed this result and found the biggest barrier to creating a positive rural placement experience was the lack of teaching capacity and the workload of the preceptors (Tables 2, 3).

Table 2: Barriers to and challenges of making a positive environment in an early rural placement – preceptor responses

Table 3: Factors that make a positive learning environment in an early rural placement – preceptor responses

Reciprocity between school, preceptor, and student

In the interviews it was identified that the quality of a student’s experience is determined by ongoing support and commitment from the school, the preceptor, and the student.

Participants stated that it is important for students to be given proper supports from the university to feel comfortable learning in a new environment. The provision of dedicated student housing arranged by the university was identified as being essential, as Felix stated:

Give them a space, give them a sense of that’s where we go when we get there. It takes away some of the uncertainty or the newness of it, makes it more comfortable.

Anne noted some of the challenges working with the university:

… integrating what the school wishes into the reality of rural small general practice. Sometimes it’s more fluid than they might perhaps like in terms of the agenda.

Preceptors also discussed some of their perceptions of the students. Anne highlighted the importance of helping students integrate into the community:

We’re fortunate to have a physician recruiter who takes on that piece around welcoming students, and certainly I think the feedback we’ve had is that it has been one of the highlights for them, it shows how intentional the recruiter is in terms of welcome, getting them out into the community and setting them up to do things in the community.

One participant, Maggie, voiced displeasure at the lack of NOSM U grads returning to her community after their placement.

These are people that are meant to be keen on rural. And we’re in a recruiting phase and there’s no interest from NOSM U grads coming and setting up practice here.

She further discussed that some students seem distracted by being away from home, and do not participate in community activities on weekends.

… the theoretical benefit is that they will see these as exciting places to practice and come back. The challenges are these they don’t like many of them, don’t like moving around a lot ... miss where they’re coming from, find themselves at loose ends after hours and that can be a challenge.

In the survey results, respondents further identified that lack of student engagement/buy-in was a barrier to creating a positive environment (Table 2).

Discussion

This study used preceptors’ perspectives to explore factors that create a positive early rural placement for undergraduate medical students. Our findings indicate that there is moderate consensus on the purpose of early rural placements among preceptors (theme: ‘Role of placements: a bridge between books and care’), that the heavy workload for preceptors could lead to burnout and placements might deter students from rural practice (theme: ‘It’s a double-edged sword’), and that the student, the preceptor, and the school all play important roles in creating positive early rural placement experiences (theme: ‘Reciprocity between school, preceptor, and student’). Understanding the preceptors’ views on positive early rural placements may allow for both preceptors and students to better align their goals. In doing so, they can create a mutually positive experience, which can potentially lead to increased rural intent or rural practice among students and reduce strain among preceptors and rural health systems.

Our study found that, in relation to the aims of early rural placements, preceptors’ responses from the interviews slightly differed from those recorded in the survey. Similar to a review on longitudinal community and hospital placements in medical education, the interviews conducted in this study suggested that RRCPs play a transitionary role in the integration of medical knowledge into clinical settings and for students to understand the rural patient and lifestyle26. However, the survey suggested sparking rural interest was most important. Based on the aim of a rural placement, a preceptor may value certain aspects of a placement over others, and this focus could change a student's perception of rural medical practice. For example, if a preceptor believes sparking interest in rural medicine is important, they might select experiences that showcase the unique scope of practice and the variety of clinical activities in the rural north27. However, if a preceptor is more concerned with the integration of pre-clinical learning, they might select more straightforward patients that align with the body-systems-based curriculum of second year. Having both preceptor and student participate in a dialogue about the purpose of their placement with opportunities for student and preceptor choice may allow for a mutually beneficial experience.

Throughout any rural placement there will be multiple competing interests and goals between education curriculum, clinical experience, community experiences, mentorship opportunities, and individual needs. Based on NOSM U’s mission of improving the health of Northern Ontarians, it is critical that these placements spark and support interest in rural medical practice. Previous research on NOSM U’s approach has suggested including mandatory community exploration experiences in the curriculum to engage with the community and promote rural medicine and associated lifestyle22. However, simply adding something to the curriculum does not necessitate a meaningful learning experience. Designers of these placements should use Maslow’s hierarchy of needs as students need to understand how engaging with the community will help students realize their goals of becoming physicians28.

The results from the interviews suggest that certain aspects of rural placement may make students uncomfortable and deter them from rural practice. Including pre-placement curriculum that addresses common rural challenges – for example how to deal with running into patients in the community, confronting loneliness, or having more clinical courage – might help students have a positive rural placement and encourage future rural work. Similar to other studies, this study also found that one of the barriers to rural placements was the increased workload on the preceptor29,30. Without close attention to these ongoing risks, these rural placements can increase the possibility of burnout among rural physicians acting as preceptors. One solution could be to make use of a team approach to precept students. Formally including office staff to help with administrative duties, physician recruiters to act as a guide to the community, and allied health professions to allow students to see patients through a different lens may help reduce the load on the physician preceptor so that they can focus on student’s experience in the clinical learning environment and allow the students to enjoy the community.

One of the more concerning barriers that was highlighted in the interviews with preceptors was the frustration that occurs when communities are unable to recruit graduating medical students. As an upstream health policy strategy NOSM U was established to address the physician workforce challenges in Northern Ontario by training and retaining doctors to serve these rural towns. However, for a site that has been an RRCP site since NOSM U’s inception, but the community has been unable to recruit physicians since becoming part of NOSM U’s educational program, it might be both difficult and frustrating to continue to commit the time and energy necessary for creating positive RRCP experiences. A potential solution could be for rural communities to have dedicated spots in the undergraduate medical school program, an adapted ‘grow your own’ return-of-service approach, specifically for some of the communities that take on students but are unable to then recruit them as full-time doctors31. In this way students could be identified by the community, given a reduced tuition payment by the community, they could do their placements in that community, and in return they would be establishing relationships with the preceptors and patients of that place and commit to serving the community after graduation. This could both help to reduce preceptor burnout and provide health care for more vulnerable communities.

The preceptors had various suggestions for improving placements, from having more than just student dwellings to a place that resonates with the concept of home, harmonizing the school’s objective with the demands of reality, and an intentional welcoming to the community. Because NOSM U is founded on a social accountability mandate that aims to engage communities, healthcare organizations, and professional groups, there should be formal mechanisms to ensure the needs of all these groups are being met32.

The interview data from this study highlighted incongruity between the extent to which many students and preceptors valued community participation, with the former being less inclined. For instance, results from the interviews suggest that, during RRCPs, students would travel home on weekends, rather than embrace life in the rural community. A similar finding was captured in the survey as respondents reported lack of student engagement as one of the biggest barriers to RRCPs. NOSM U aims to recruit students who are interested in rural medicine; however, the results from both the interview and survey suggest that NOSM U’s students are not engaging with the rural communities where they train. Utilizing a place-based education approach may help to alleviate students’ reluctance to reside in the community throughout their placement. Proponents of place-based education highlight the value in using places outside of the clinic for education33. Work by Ross and colleagues (2020) has examined rural placements using this theory and suggested that students have a different ‘place-relationship’ than their teachers in terms of the social dimension of place34. Another potential solution would be to examine the necessity and timing of examinations surrounding rural placements. Alleviating academic commitments during that time may allow for more opportunities to connect with the community. Future research is needed to address how to build these social dimensions for students to help them develop a sense of place in the rural community during placement.

One of the potential limitations of this study is the lack of background data on the participant preceptors. Including a question on how many years the preceptor has been taking on students, the type of clinical practice the preceptor is involved with, or the preceptor’s teaching philosophy may help to explain why there was variation in responses. Another potential limitation is the low sample size of the interviews. This was mitigated by creating a survey based on the interview results to help strengthen the findings of this study. Finally, this study was done in one school, and one region may reflect the institutional culture and might not be transferable to other educational settings.

Conclusion

This study explored rural preceptors' beliefs on what contributes to positive early rural placements for students. Preceptors discussed the role of early rural placements, the risks associated with these placements, and the role the student, preceptor, and school play in making these experiences positive. Beyond these identified themes the results prove that to create positive early rural experiences a multitude of factors must be considered and work in harmony. Failing to consider these aspects may result in negative experiences for both students and preceptors. This research is valuable to any institution that is actively focusing on creating positive placement experiences that align with an institutional mission.

Funding

This study received funding from the NOSMFA Research Development Fund.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

You might also be interested in:

2017 - Health care in high school athletics in West Virginia

2009 - Challenges faced in implementation of a telehealth enabled chronic wound care system