Introduction

Decentralized curricular models are potentially vulnerable for learning environment deterioration due to their remote localization and limited student numbers. Prior investigations of learning environments in decentralized medical curricula describe inconsistent results, and are limited to certain geographical areas – excluding, for example, Scandinavia. The aim of this study was to compare learning environment perceptions of students in a decentralized curricular model in Norway to those of their urban counterparts, and relate the findings to international comparable data.

Learning environment

The learning environment has proved important for medical students’ wellbeing, satisfaction and academic results1-3. Although learning environments are complex and multifactorial, certain initiatives seem to affect them positively. Among these initiatives are integration of learners as active members of communities of practice and tailored guidance by teachers to aid learners’ development of self-regulation4. Furthermore, employing problem-based learning as opposed to lecture-based instruction has been shown to increase learning environment satisfaction5.

To achieve an optimal learning environment, the first step is to diagnose the current situation. Reflecting the complexity of measuring this variable, numerous inventories have been developed for this purpose6. One of the most frequently used within medical education is the Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure (DREEM)7. Existing literature investigating learning environments utilizing DREEM take on different approaches: examining one cohort or institution, comparing within or between institutions, and exploring correlations between learning environment perception and other variables such as academic achievement and learning styles3.

Decentralized curricula

Decentralized medical education has existed for more than four decades8, and interest is increasing. Reasons include needs for an expanded repertoire of learning arenas to meet the growing demand for medical doctors, as well as workforce maldistribution across remote areas. While educational quality has been questioned internationally9 and locally10, there is now growing evidence that decentralized models provide adequate learning opportunities for students11,12.

Some comparative DREEM studies describe more positive learning environment perceptions among students enrolled in smaller rather than larger clinical training sites when comparing urban and rural programs13, or within different-sized rural programs11. Others, however, have found minor variations within different-sized training sites14,15, or more positive perceptions among students in larger compared to smaller rural hospitals16. No previous studies have looked into learning environment perception of students in a decentralized curriculum in Scandinavia.

Thus, due to inconsistency in previous results and insufficient knowledge about learning environments in decentralized curricula, we aimed to evaluate students’ learning environment perceptions in a decentralized curriculum in Norway and compare it with that of their urban counterparts, using the DREEM questionnaire. Moreover, we wanted to compare our findings to previously reported learning environment data from other medical curricula internationally.

Methods

This comparative cross-sectional study was conducted in 2021–2023.

Context

The medical degree program at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology is a 6-year undergraduate curriculum, located in Trondheim and integrated with Trondheim University Hospital. For the cohorts included in this study, approximately 135 students per cohort were matriculated. In 2018, an optional decentralized curriculum comprising study years 3 and 4 was established, accommodating a maximum of 16 students per cohort. Here, the clinical training takes place in regional hospitals and in primary healthcare settings, 80–190 km from Trondheim. Learning objectives and summative assessments are identical for the decentralized and the urban curriculum, but the curricular organization differs somewhat. While both curricula apply problem-based learning, at the decentralized site plenary lectures have been replaced by flipped classroom activities, and clinical activities are longitudinally integrated rather than organized in discipline-specific blocks17. Enrollment in the decentralized curriculum is voluntary, and for the participants included in this study, all students who requested participation were admitted.

For both curricula, years 3 and 4 comprise clinical learning, and students get clinical exposure within a broad range of hospital-based medical specialties (eg internal medicine, surgery, neurology, gynecology, pediatrics, imaging, and intensive care). End-of-year and end-of-semester examinations are applied for years 3 and 4, respectively.

Participants and data collection

Year 4 students in the period from 2021 to 2023 were invited to participate in the study. Thus, the 2017, 2018 and 2019 cohorts (n=395) were approached, of which 362 students were enrolled in the urban curriculum, and 33 students in the decentralized curriculum. Power calculations were performed before commencing the study, showing a power of 0.84 for detecting a difference of 13 points in overall DREEM score with sample sizes of 30 in group 1 and 100 in group 2.

The secure-server tool www.nettskjema.no was used for data collection. Students answered the questionnaire during the final 2 months of year 4.

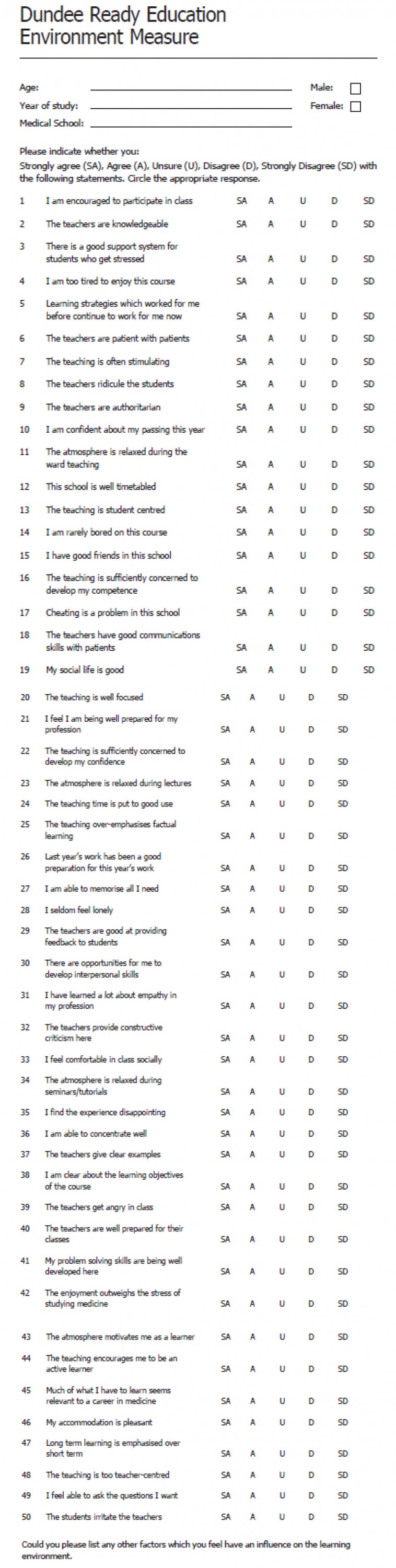

The DREEM questionnaire

DREEM contains 50 items, allocated to five subscales: students’ perception of learning, students’ perception of teachers, students’ academic self-perceptions, students’ perception of atmosphere, and students’ social self-perceptions. Each item was rated on a five-point Likert-scale from ‘strongly agree’ (4) to ‘strongly disagree’ (0), with a maximum total score of 200. A proposed interpretation of the total score suggests that 0–50 implies a ‘very poor’ environment, 51–100 ‘plenty of problems’, 101–150 ‘more positive than negative’, and 151–200 ‘excellent' environment18. Permission to translate and use DREEM was obtained from the developers of the questionnaire.

DREEM is widely used in medical education research internationally, providing an extensive pool of studies as a basis for comparison. Medical educators from diverse backgrounds participated in the development of the tool, and it is argued by the developers to be culturally neutral, making it universally applicable and relevant18. DREEM has been translated into several languages, including Swedish19. A Norwegian master’s student did a translation into Norwegian, although the result has not been published in a research journal20.

Translation of DREEM

We systematically translated the original English version of DREEM into Norwegian, directed by Beaton et al’s ‘Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures’21. This process included two separate forward translations, back translation by two independent native English speakers, and a review of all versions by a qualified committee, consisting of the authors of this article, one additional clinical educator and a professor in pedagogy. We looked to the existing Norwegian translation20 in the process but ended up with a slightly different result. The prefinal version was pretested by year 5 students (non-participants in the current study), and modifications were implemented based on their feedback. The committee reached consensus on the final version. The original DREEM and the final version of the Norwegian DREEM as translated here are in Appendix I. Apart from the translation process, further validation of the psychometric properties of the Norwegian version has not been undertaken in this study. However, acceptable validity and reliability scores have been reported for the original DREEM and other translated versions, including the Swedish translation22-24.

Data analysis

Overall DREEM score and subscale scores for students enrolled in the decentralized curriculum were compared to that of students in the urban program by applying the independent t-test. STATA v18.0 (StataCorp; https://www.stata.com) was utilized for statistical analysis. For single items, means and descriptive statistics (median and quartiles) were calculated.

Ethics approval

Study participation was voluntary. As an incentive to increase the response rate, respondents were offered an opportunity to win a gift card valued at 500 Norwegian kroner (A$75 at the time of study). Urban program students submitted their responses anonymously. Students in the decentralized curriculum were identifiable to researcher ISJ. Written informed consent was obtained from these students. This was done as the current study is part of an extended project evaluating the decentralized curriculum, enabling different parts of the evaluation data to be correlated. This was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (no. 450319). All data were processed in terms of confidentiality and protection.

Results

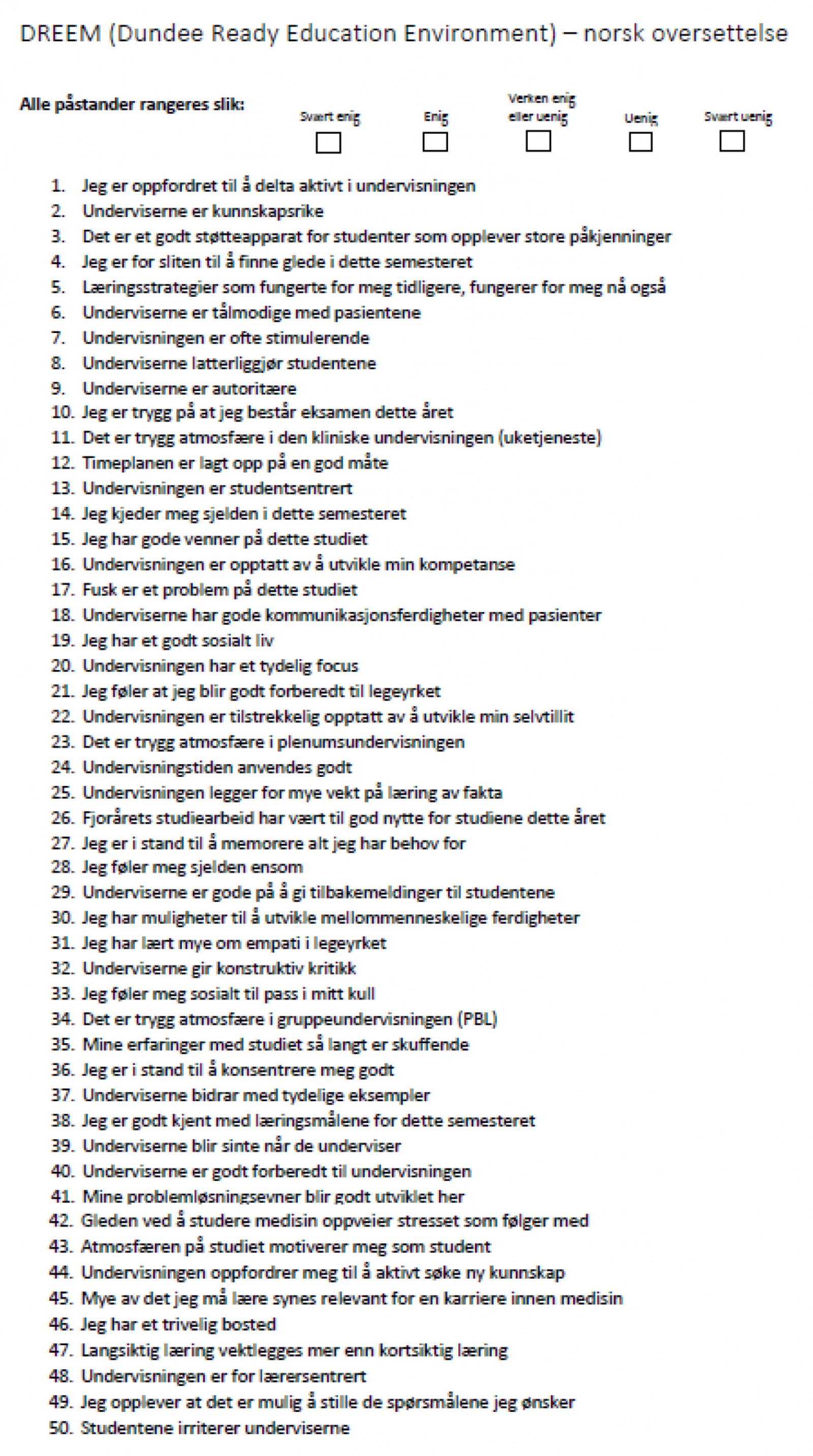

A total of 216 urban-site students (response rate 60%) and 31 decentralized-site students (response rate 94%) completed the survey. Mean overall DREEM score for all students was 133.5. Students in the decentralized curriculum scored significantly higher on all subscales (Table 1). The subscale ‘Perception of learning’ displayed the largest difference between the two groups, while ‘Social self-perception’ differed the least.

Mean score and variability for each item are shown in Figure 1. For negative items (marked with *) the scoring is reversed, which is accounted for in the analysis. Hence, a negative item ranked as ‘strongly agree’ equals 0 points instead of 4 points, ‘agree’ equals 1 point instead of 3 points, and so on. Most items were scored higher by the decentralized students, with some exceptions. Items that urban students scored higher than decentralized students were ‘Learning strategies which worked for me before continue to work for me now’, ‘My social life is good’, and ‘I seldom feel lonely’.

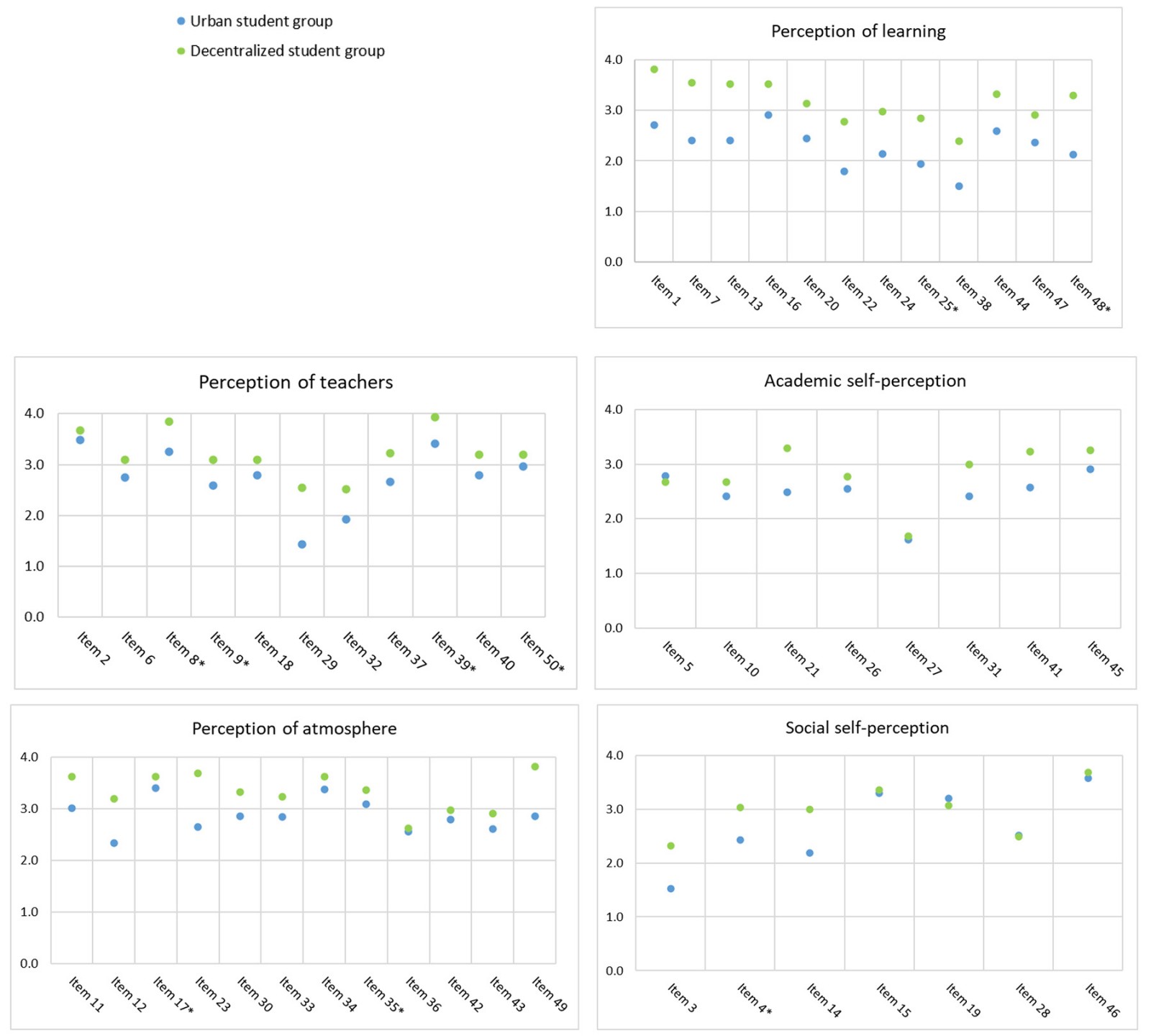

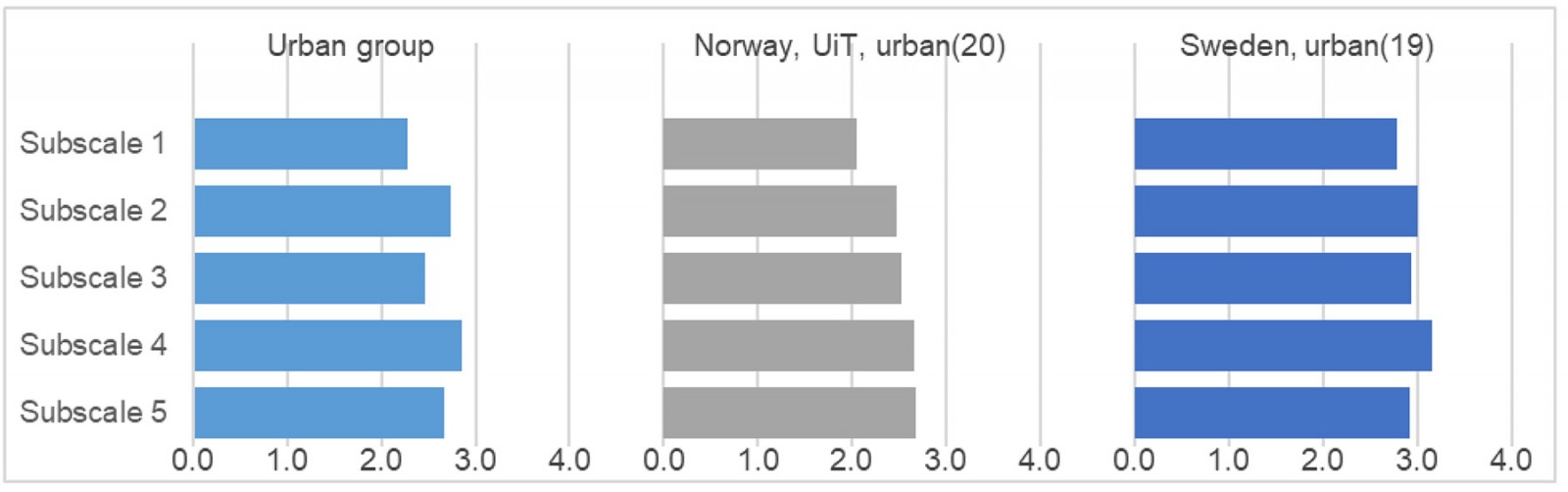

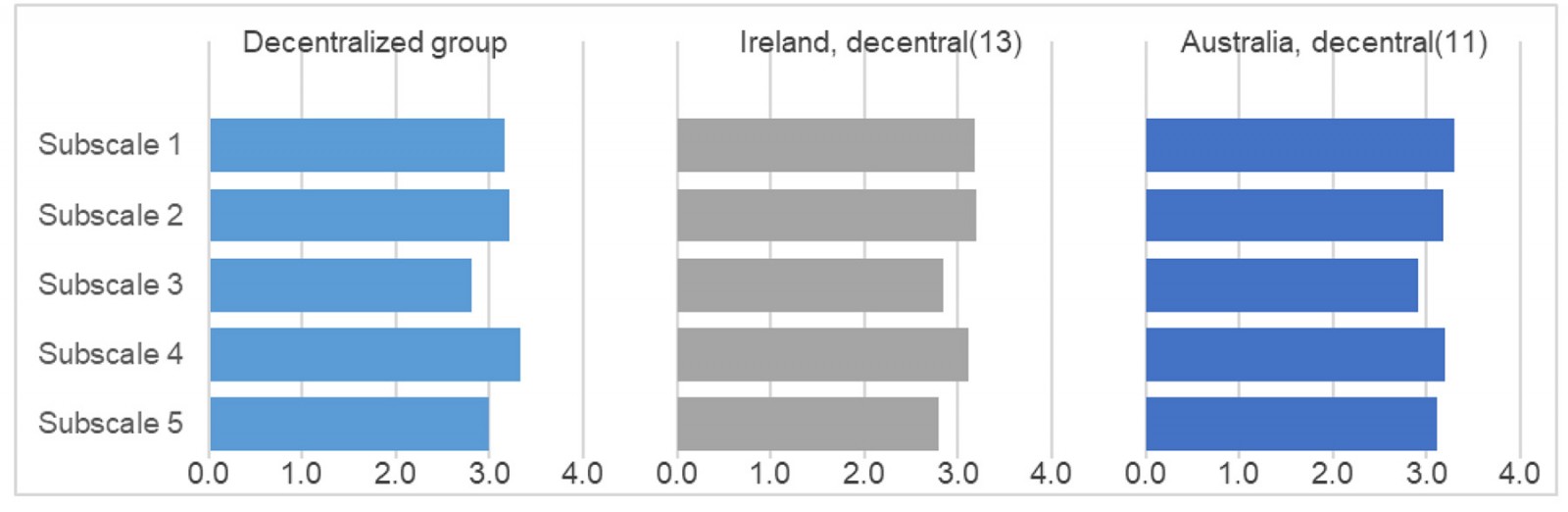

Comparison with studies performed in other urban and decentralized contexts are shown in Figures 2 and 3.

Table 1: Mean Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure overall and subscale scores and 95% confidence intervals for urban and decentralized student groups, Norwegian University of Science and Technology

| Scale/subscale | Urban | Decentralized | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean score n(%) | 95%CI | Mean score n(%) | 95%CI | ||

| Overall DREEM score (max. 200) | 130.1 (65.1) | 127.8–132.5 | 156.8 (78.4) | 150.6–163.1 | <0.01** |

| Perception of learning (max. 48) | 27.3 (56.9) | 26.5–28.1 | 38.0 (79.2) | 36.0–40.0 | <0.01** |

| Perception of teachers (max. 44) | 30.1 (68.4) | 29.5–30.6 | 35.4 (80.5) | 34.2–36.7 | <0.01** |

| Academic self-perception (max. 32) | 19.8 (61.9) | 19.2–20.3 | 22.5 (70.3) | 21.2–23.8 | <0.01** |

| Perception of atmosphere (max. 48) | 34.3 (71.5) | 33.6–35.0 | 39.9 (83.1) | 38.4–41.5 | <0.01** |

| Social self-perception (max. 28) | 18.7 (66.8) | 18.2–19.2 | 20.9 (74.6) | 19.5–22.4 | <0.01** |

** Significant intersite differences (p<0.05) were found for overall score and all subscale scores.

CI, confidence interval. DREEM, Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure.

Figure 1: Mean Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure scores per item within each subscale, for urban and decentralized student groups, Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

Figure 1: Mean Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure scores per item within each subscale, for urban and decentralized student groups, Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

Figure 2: Subscale scores per item for the urban group in the present study (Norwegian University of Science and Technology) and other urban-site student groups.

Figure 2: Subscale scores per item for the urban group in the present study (Norwegian University of Science and Technology) and other urban-site student groups.

Figure 3: Subscale scores per item for the decentralized group in the present study (Norwegian University of Science and Technology) and other decentralized-site student groups.

Figure 3: Subscale scores per item for the decentralized group in the present study (Norwegian University of Science and Technology) and other decentralized-site student groups.

Discussion

Students in both the decentralized and the urban curricula were relatively satisfied with their learning environment, with the decentralized student group’s overall DREEM score classifying as ‘excellent’ and the urban group’s as ‘more positive than negative’18.

The DREEM inventory broadly investigates various aspects of students’ learning environments. The most pronounced difference between the two student groups examined in this study were seen in students’ perception of learning, a subscale that indicates students’ views on the learning activities in their curriculum. Furthermore, distinct mean score differences were found in students’ perceptions of the skills and abilities of their teachers, and students’ notions of the atmosphere during teaching situations and at the study program in general. Several factors are possible explanations for these findings.

Dissimilarities related to curricular organization and type of learning activities applied at the two study sites may play a decisive role. In the decentralized curriculum, students are to a large extent activated through regular flipped classroom activities that are longitudinally integrated through the semester, while more traditional lecture-based teaching takes place in the urban curriculum. Circumstances related to this pedagogical disparity are reflected in the mentioned subscales. Within the subscale ‘Perception of learning’, the item scores for ‘I am encouraged to participate in class’ and ‘The teaching is student centered’ elucidate this, being two of the items with largest intersite score differences. The score gap on the item ‘The teachers are good at providing feedback to the students’ within ‘Perception of teachers’ may further illustrate an outcome of being exposed to flipped classroom activities as compared to lecture-based formats.

Both the urban and the decentralized student group scored ‘Perception of atmosphere’, the highest of all five subscales, with the decentralized group being somewhat more satisfied with the atmosphere in total. The largest group score difference was seen for the item ‘The atmosphere is relaxed during lectures’ (the term ‘lecture’ was replaced by ‘plenary teaching’ in the Norwegian translation to accommodate for both lectures and flipped classroom activities); a slightly smaller difference was seen for ‘The atmosphere is relaxed during the ward teaching’, and only a minor difference was seen for ‘The atmosphere is relaxed during seminars/tutorials’ (seminars/tutorials were specified as problem-based learning in the Norwegian translation). This directly reflects variation in curricular organization between the two sites, as lecture formats diverge the most (traditional plenary lectures at the urban site and flipped classroom at the decentralized site), thereafter formats of ward teaching (some similarities, but more outpatient exposure and fewer students per group at the decentralized site), while formats of tutorials/ problem-based learning sessions are quite similar. That both student groups scored perception of atmosphere rather highly may partly be explained by the less hierarchical culture prevailing in the Scandinavian pedagogical context.

The localization of the two curricula is another independent element possibly contributing to different learning environment experiences. Decentralized programs tend to be characterized by fewer students, fewer teachers and less specialized expertise among these, and fewer student welfare facilities. The limited student numbers may result in more feedback, closer follow-up, and enhanced encouragement and sense of responsibility among students for contributing in learner-centered activities. Few teachers per subject area may cause more student–teacher continuity, which allows for development of relations between students and their teachers. Such continuity is one of the core principles of Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships – the curricular model on which the present decentralized program is founded17. Considering the findings in this study, it seems like this principle contributes positively to the learning environment. Extreme scores for ‘The teachers ridicule the student’ (3.8) and ‘The teachers get angry in class’ (3.9) indicate that teachers at the decentralized site are good at caring. However, it should be noted that despite the decentralized students’ relatively high scores on items related to feedback, as mentioned above, both the urban and the decentralized groups had fairly low absolute scores on these items. This coincides with international DREEM studies3 and can be seen as a collective call for improvement in this regard.

The combination of few students, continuous relationships with teachers, learner-centered activities, and vertical integration of subjects may contribute to students feeling psychologically safe in the decentralized curriculum. These students scored particularly high on the items ‘I feel able to ask the questions I want’ and ‘The atmosphere is relaxed during lectures’ – scores that could indicate students experiencing their learning environment as safe, and absence of fear of being humiliated. The importance of ensuring a welcoming community for novice members is stressed in discussions of implications for medical education when viewing medicine as a community of practice25. To support the transition from peripheral to actual participation, the community must exercise inclusivity and make sure everyone has a sense of belonging. Perhaps the conditions in a smaller, decentralized model are more conducive to this. However, taking into account the significance of a safe learning environment for students’ learning, this should be strived for in all educational contexts.

Notably, decentralized models typically offer fewer welfare facilities for students. Therefore, the social consequences of transitioning from urban to decentralized training was one of the concerns related to the establishment of the new program. In this, admittedly limited, sample however, this does not seem to be an issue. It should be mentioned that several of the decentralized students came from the area where the program is located, or from surrounding areas, and thus may have established social networks before commencing the program. However, two items in this category were scored slightly higher by the urban group than by the decentralized group: ‘My social life is good’ and ‘I seldom feel lonely’ – indicating that some improvement is still needed to meet not only the academic requirements, but also the social needs of the decentralized students.

Academic self-perceptions were mostly similar for the two student groups, with some exceptions. The largest intersite discrepancy was seen for ‘I feel I am being well prepared for my profession’. Applying the theory of community of practice may offer a plausible interpretation: Higher levels of participation in the community, which is assumed to occur in the decentralized curriculum due to the low student numbers and the high student–teacher continuity, entails more exposure to realistic clinical situations, providing increased access to become familiarized with the profession. Moreover, integration in the community can aid students’ development of their professional identities, which may also be a way of preparing them for their upcoming profession25. This is the only subscale to receive a mean score of less than 3.0 for the decentralized students. Looking to previous DREEM studies, medical students tend to have low scores in this category. This has been explained by the nature of medical studies, being demanding and overwhelming in terms of workload for all students15.

Our results are comparable to those of other urban and decentralized programs internationally. Similar to our findings, other decentralized programs seem to score lower on the self-perception subscales, and higher on the other subscales11,13. Perception of learning tends to be scored lower for urban programs19,20, as reflected in our study as well. For all studies included in the comparison (Fig2, Fig3), students perceive the atmosphere as highly positive.

Limitations and strengths

One limitation of this study was that students in the decentralized group provided their name with their survey response. This could possibly have affected their scoring, as a means of (intentionally or unintentionally) pleasing the researchers. Nonetheless, these students were only identifiable to researcher ISJ, not the program leader nor any other researcher. However, differences in the organization of the learning activities being directly reflected in students’ responses in the questionnaire increases the trustworthiness of the data. The two student groups are in agreement about the ability to memorize all that is needed (item 27), which further strengthens this notion. Additionally, the scoring tendency for each group is to a great extent similar for all items. Hence, response bias may be present, but is probably of limited extent.

Self-selection to the decentralized curriculum could present a bias as it possibly attracts students who are favorably disposed to the features of this model. These features include both the curricular organization and the geographical localization.

The response rate in the urban group of 60% can raise questions about the representativeness of the received responses in this group. Still, the results were consistent across the three included cohorts, which points towards measurement credibility despite the mediocre level of participation. The high response rate in the decentralized group (94%), on the other hand, increases the credibility of the responses from this group.

Conclusion

Both the urban and the decentralized groups experienced their learning environments as positive. Educational atmosphere stood out as being particularly highly perceived, which may be attributed to the less hierarchical Scandinavian culture. The decentralized student group was more satisfied with their learning environment in general, and they perceived the learning as especially positive. This could be due to the use of flipped classroom and the structuring of learning activities in a longitudinal integrated manner. The small size of the student group and successful community integration may also be of importance. More research is needed to explore each factor’s contribution to the learning environment, and potential cause-and-effect relationships.

Acknowledgements

Vidar Gynnild, Marie Thoresen, Robert James Heaslip, Sarah Beth Evans-Jordan, and Nivetha Puvanendran contributed to the translation process of the DREEM questionnaire.

Funding

No external funding was received for this study. The PhD scholarship of the first author was funded by the Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.