Introduction

Despite educational and policy efforts, the projected healthcare professional shortage in the United States is expected to increase in the coming years, with rural and underserved communities amongst those that will be most affected1,2. It is vital to investigate novel ways of recruitment and retention for these most vulnerable communities. The juncture between the conclusion of formal training and initial practice in a rural community is a critical time that influences retention3. To that end, Mountain Area Health Education Center (MAHEC) developed a Rural Fellowship program with the intention of facilitating both the placement and continued development of recent graduates from family medicine and one clinical pharmacy residency program in rural western North Carolina (WNC). The Rural Fellowship addresses early challenges faced by newly graduated clinicians: isolation, inexperience, purpose, and community integration2. The curriculum implemented a novel framework to address identified factors that support the transition to rural practice and retention for first-year providers. The focus of the present study centered on family medicine providers, but also included one rural clinical pharmacist in the cohort. The inclusion of clinical pharmacy was a first step towards making these cohorts more interprofessional while also recognizing the importance of team-based care in rural clinics. The unique financial and curricular model protects a full-time salary and, in the setting of rural clinical practice, preserves educational time for ongoing professional development. Since the Fellowship’s inception in 2017, 30 participants have completed the program. For the purposes of this study, a group of eight former Rural Fellows were selected for the interview process: seven family medicine physicians and one clinical pharmacist.

Efforts to rectify the healthcare workforce inequities in rural areas have traditionally focused on pathway programs, admissions, and increased rural clinical experiences. Medical students from rural backgrounds tend to display a higher interest in practicing rural medicine4. Research has shown that medical students’ exposure to rural medicine during a rotation or summer program can strengthen their understanding of, and interest in, rural practice5,6. Furthermore, recent evidence has shown a strong positive correlation between rural track programs and rural exposure during residency training and eventual rural placement upon graduation, especially for those from rural backgrounds5,7. Pipeline programs for pre-graduates and medical students, such as the Physician Shortage Area Program, have shown a similar trend of attracting physicians to rural areas8.

Beyond rural exposure during training, rare efforts have focused on post-residency rural programs as the final bridge to improve the problem of placement and retention. Post-residency training for family medicine has often focused more on specialized skill development, such as obstetrics or sports medicine9. Much of the existing research focuses on scholarships and loan-forgiveness as additional incentives for placement10. Additional models for encouraging rural placement and retention in the United Kingdom and Australia have revealed that post-residency graduates who completed a rural Fellowship had a higher likelihood of remaining in rural settings11,12. Despite this encouraging evidence, there is scant literature that demonstrates the impact of rurally focused post-Graduate Medical Education (GME) models in the United States.

The barriers to physicians’ placement and retention in rural communities are complicated and numerous. Challenges in recruiting include a perceived notion of professional and social isolation, poor access to specialty support and services, a disconnection from an academic cohort, and a lack of resources to foster physician development11,13. The goal of this evaluation is to determine the impact of this post-residency Rural Fellowship on these key factors.

Methods

Setting and participants

WNC comprises the 16 westernmost counties of North Carolina and is a mountainous, largely rural region composed of 14 rurally designated counties and two suburban counties. There are 806,232 residents currently living in WNC, 52% of whom reside in a rural county14. The largest urban center, Charlotte, NC, is approximately a 2-hour drive from our largest city, Asheville.

In collaboration with rural clinical practices in the westernmost 16 counties of North Carolina, we designed a Fellowship for healthcare providers transitioning from residency into their first year of practice. The Fellowship administration team, composed of a physician clinical director and program manager, focused on recruitment of physicians interested in practicing in a rural setting and collaborated with rural practices for prioritized placement where workforce needs exist. The Fellowship model retained a commitment of 80% of Fellows’ time practicing rural clinical medicine in partnership with employing clinical organizations, and protected 20% of their workweek for Fellowship activities through MAHEC. State-appropriated funds and grants supported the Fellowship time at 20% of a full first-year salary.

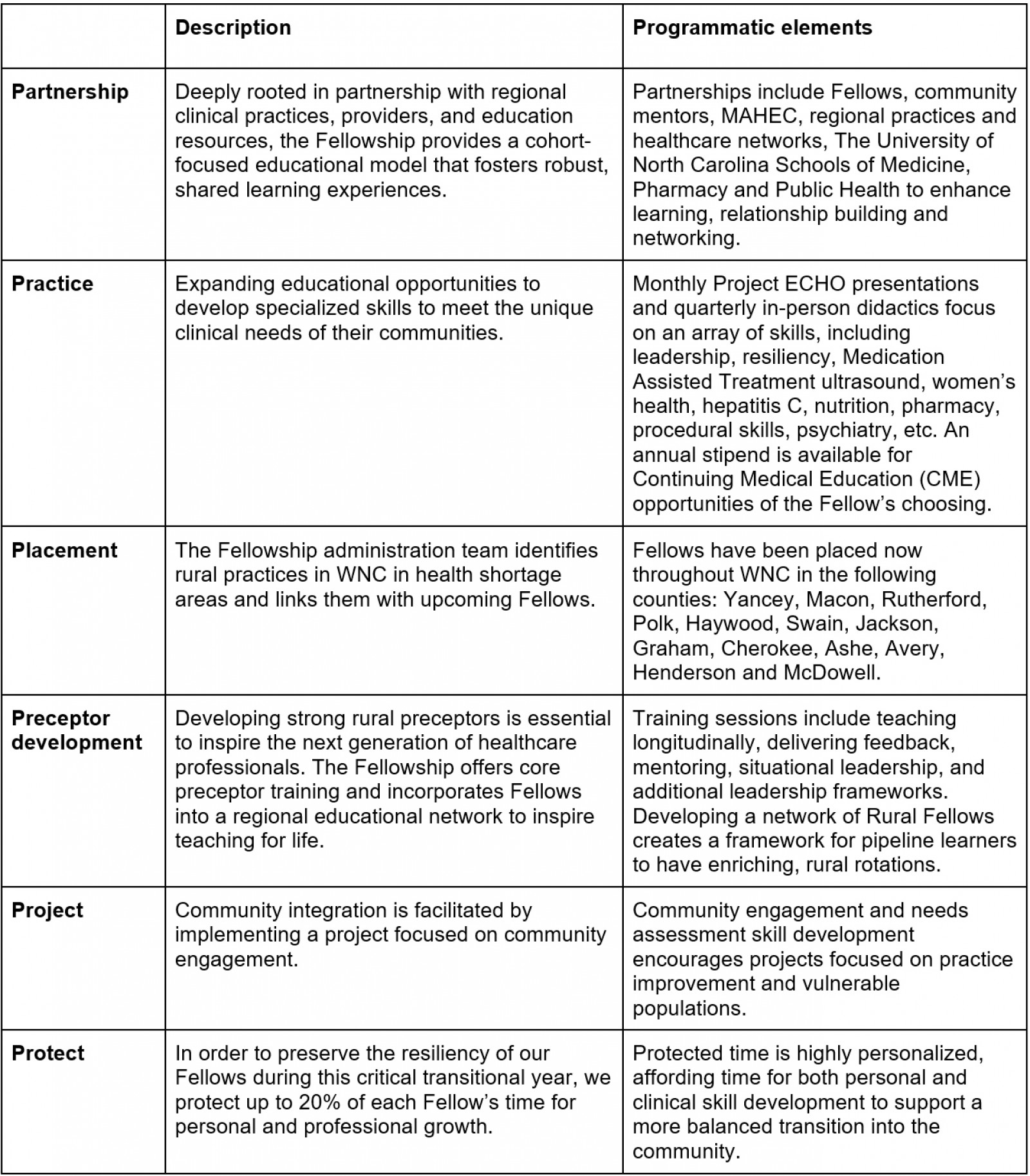

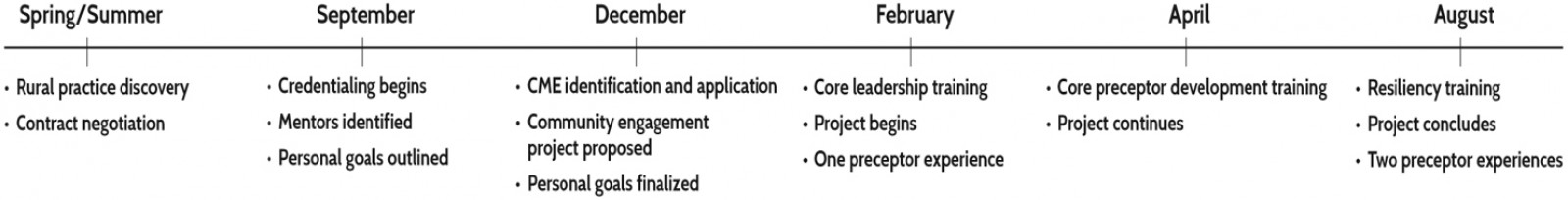

The Rural Fellowship model curriculum is organized around the '6 Ps,' depicted in Figure 1. The curricular components related to each P are detailed in Table 1. Over the course of their first year in practice, Fellows share in the curriculum described by the timeline in Figure 2. The Fellowship administration team offers individualized support to each Rural Fellow throughout the program via site visits to the Fellows’ practices for one-on-one meetings, frequent phone and email communication, and six retreats throughout the year. Each of the different disciplines are exposed to the same curriculum. In the spring and summer before the Fellowship year begins, applicants discover rural practice employment opportunities and negotiate their employment contracts with the help of the Fellowship administration team as needed. When the Fellowship year begins in October, the Rural Fellows are official employees of a clinic, hospital, or federally qualified health center, and are simultaneously engaged in MAHEC’s Fellowship program through a contractual agreement with the practice.

Beginning in September, the Fellowship assists Fellows with the credentialing process, outlining personal goals and identifying community mentors for their time in the program. Fellows individualize their development plan by identifying desired Continuing Medical Education (CME) opportunities, finalizing their goals, and engaging in their community project proposal by December. Core leadership training takes place in February; by this time, Fellows have had at least one preceptor experience, and have begun their community project. April brings core leadership training, one additional precepting experience, and continuation of community engagement project activities. As the Rural Fellowship curriculum draws to a close in August, Fellows participate in resiliency training, at least two precepting experiences, and conclude their community project. Throughout the year, Fellows participate in monthly virtual Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) education sessions and quarterly in-person didactic sessions. Monthly ECHO sessions reinforce curricular elements that help enhance key clinical knowledge needed for effective rural practice, such as behavioral health, substance use disorder, women’s health and other primary care topics. Furthermore, the ECHO sessions seek to build a longitudinal learning community among the cohort. The Fellowship program offers a unique blend of universal curriculum focused on personal and professional development, with individualized opportunities that allow each Fellow to maximize their experience by focusing on projects and engaging in CME that best suits their interests and needs. This allows Fellowship participants, regardless of specialty or credentials, to have an experience that is simultaneously unique and unified.

Figure 1: The 6 Ps: a novel cohort Fellowship.

Figure 1: The 6 Ps: a novel cohort Fellowship.

Table 1: The 6 Ps defined: the curricular components related to each P

Figure 2: The Rural Fellowship year at a glance.

Figure 2: The Rural Fellowship year at a glance.

Study design

During the winter of 2020, we conducted semi-structured interviews with all eight past Fellows who completed the program. They were asked to describe their experiences and detail the Fellowship’s impact on their preparation for rural medicine and desire to stay in rural practice. Furthermore, they were asked to discuss aspects of the Rural Fellowship that were done well and areas to be strengthened. Members of University of North Carolina Health Sciences at MAHEC’s Research Department conducted one-on-one interviews with the Fellows (CH, JF). The interviewers were unknown to the interviewees and the interviews were conducted in person. Fellows were tracked on an annual basis for 5 years following the initial interview to further evaluate rural retention rates.

Data analysis

A thematic data analysis design was implemented to identify and report themes emerging from the data15. Four authors (CH, GBD, RL, JF) inductively coded the interview transcripts. After the interviews were coded and major themes were identified among the coders, the results were presented to the four additional clinical and administrative members of the team to define and refine themes until content saturation and agreement were achieved. The team members responsible for recruiting and running the program did not participate in any of the interviews. The codes and themes were created independently of the '6 Ps' framework. Once the final themes were agreed upon, the findings were contextualized based on the '6 Ps' framework.

Ethics approval

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Institutional Review Board deemed this program evaluation exempt.

Results

Interviewees’ reflections on each of the '6 Ps' are described below. During the data analysis process, codes were created and categorized into the six themes as outlined below. Overall, participants reinforced the vital support the Fellowship provided and all would recommend the Fellowship to others. Each of these themes highlighted vital aspects of the Fellows’ success, most notably the cohort experience allowing for increased social support, preceptor development, and engagement with learners, and the protected time for personal exploration, professional development, and resiliency.

Partnership (peer experience)

When Fellows were asked about the most impactful part of the Fellowship, the peer cohort experience was most often mentioned. These connections were especially important due to their rural, often-isolated placements. The opportunity to have a shared experience with other first-year practicing rural providers was powerful:

It was good to have the opportunities to stay connected to a small cohort of colleagues who were doing similar work, trying to get established in a rural setting, facing similar challenges. (Interviewee #4)

Brainstorming with their peers who were sharing the same experiences also allowed them to address complex clinical care issues related to rural practice management. As one Fellow mentioned,

… it was interesting to all get together and talk about our trials and tribulations … [about] trying to build out a full-scope practice. And it was helpful to talk to them about what their issues were and to help them. (Interviewee #3)

Learning in practice

The practice of medicine in a rural setting can inherently feel isolating and distant from the peers and colleagues that can cultivate ongoing learning. Fellows felt that ECHO sessions were a beneficial part of the Fellowship because they provided valued learning opportunities related to their practice needs. The content covered in these sessions highlighted the barriers to critical and more difficult-to-reach services, such as substance use disorder, hepatitis C treatment, behavioral health, and ultrasound. As one Fellow mentioned,

I think the ECHO model is a great idea. Again, both for disseminating knowledge, as well as fostering a little bit of connection at a distance. (Interviewee #5)

The ECHO sessions helped foster and reinforce cohort connections,

… but it was nice to feel [connected] and hear all those voices on the ECHOs. (Interviewee #6)

While Fellows did appreciate the ECHO sessions, one barrier noted by the Fellows was the inherent struggle to find a common time for cohort learning and engagement.

Rural placement

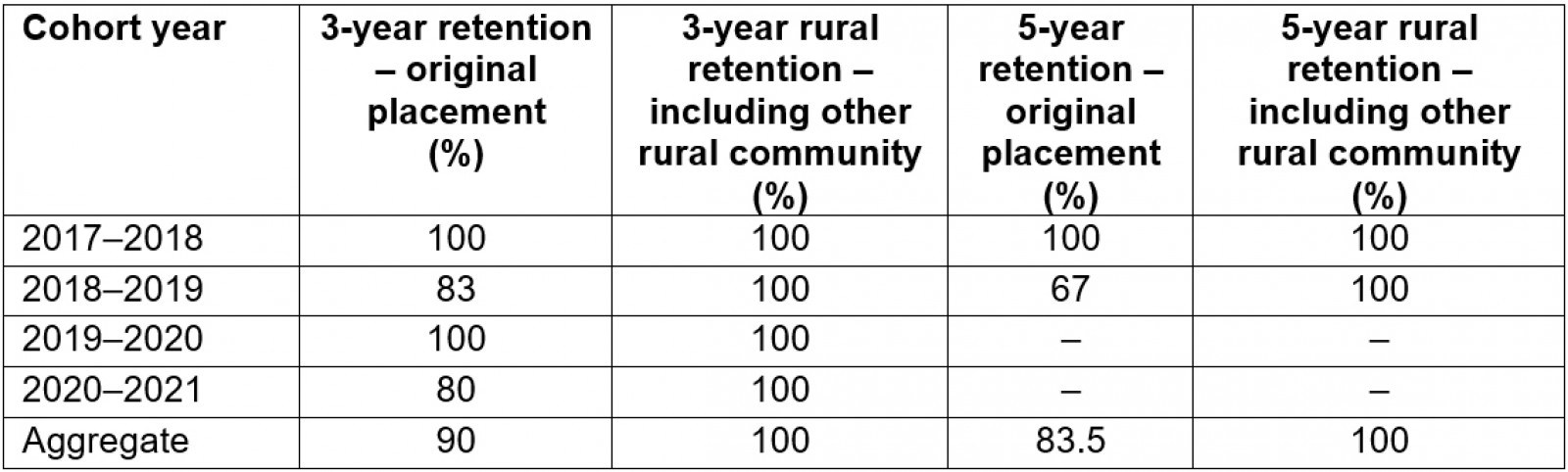

All of the Rural Fellows were interested in pursuing rural practice prior to their Fellowship year. Many chose rural practice due to their desire to provide comprehensive care, a notion that was reinforced during their Fellowship year. At three years post-fellowship, 89% of those in this study remained at their original Fellowship site and 100% are still practicing in a rural area. Table 2 outlines the 3- and 5-year retention rates of Rural Fellows in their original practice sites and in rural communities overall. Since the inception of the Rural Fellowship in 2017, Fellows have been widely distributed throughout rural counties in the WNC region. To date, Fellows have been placed in 13 of the 16, or 81%, of the westernmost counties in North Carolina. Additionally, the Fellows encompass a wide scope of medical practice needed in healthcare within a rural setting. As of October 2023, Fellow placement retention is 87% in rural WNC and 97% in rural practice overall.

I think with family medicine, to do full scope, meaning do primary care, pediatric, and extensive care and hospital care … You have to work in a really rural location because that’s the only places nowadays where family doctors still do it, be able to practice that full scope (Interviewee #7)

Table 2: Three- and five-year retention rates of Rural Fellows in their original practice sites and in rural communities overall

Preceptor development

Multiple Fellows felt that preceptor development was a highlight of the Fellowship. Every Fellow had specific preceptor development coaching and experientially supported the learning of medical students, regional undergraduate and high-school pipeline students, and family medicine residents. Several mentioned how much they enjoyed their teaching experience. As stated by one Fellow,

I think that physicians by nature are educators. We're educating our patients every day and I was really excited to extend that to teaching future physicians as well. (Interviewee #3)

The inclusion of training the Fellows to become educators also influences their careers after the Fellowship. As one Fellow mentioned,

... I’m going to continue to have longitudinal medical students ... It just helped to be a Rural Fellow and have that preceptor part of it be baked into the Rural Fellowship. (Interviewee #1)

Community engagement

In an effort to provide structured support for community engagement, each Fellow designs and implements a unique clinically focused or community-based engagement project in his or her geographic area during the Fellowship year. Planning for the projects begins in the fall, while the majority of project activities take place in the spring and wrap up in the summer months. Examples of past Fellowship projects include: providing sports medicine services in critical access areas of rural WNC; supporting regional providers’ care of patients with hepatitis concerns; and writing a column on assorted health and wellness topics for a local newspaper.

But as time went on, the [community engagement] project actually became really dominant in my Fellowship and has grown into something that has actually changed our practice and affected all of our practitioners. (Interviewee #8)

Protected time

The integrated protected time aspect of the curriculum was highly regarded among the Fellows. Multiple participants noted that the transition into the first year of rural practice can be stressful and overwhelming. Many noted that having a day outside of patient care was valuable for learning, warding off burnout, adapting to personal and clinical needs, and establishing time outside of the clinic to connect with their rural community. While a traditional schedule during the first year of medical practice is typically overwhelming, Fellows felt that the protected time allowed for an easier and smoother transition into their first year.

I think really just by allowing the [protected] time, [it helped] ward off the burnout ... I wasn’t as pressed to see a ton of patients in my first year, just allow that time to get settled ... So, it’s really the time allotment that was the valuable piece. (Interviewee #2)

Discussion

This program evaluation demonstrates a high success rate for rural placement and early retention. The analysis details the key variables that make a Rural Fellowship model impactful during the first-year transition into rural practice. Based on this initial analysis, new approaches to securing and supporting rural practice choice at the conclusion of traditional medical education should include a cohort model across multiple Fellowship sites, professional development, community engagement, protected time, and the incorporation of teaching. Findings through interviews demonstrate that such a Rural Fellowship experience effectively delivers the key rural content designed in the '6 Ps' curriculum. Not only does the Fellowship year support new clinicians’ transition to rural communities, but it expands their clinical skills and further develops the attitudes that promote resilience and retention. Furthermore, this model reveals the vital importance of instilling a deeper connection with the local community, beyond the walls of traditional practice. Sharing in this learning curriculum provides Rural Fellows with the connections to potentially facilitate future success through ongoing support, mentorship, and the sense of being connected to something bigger, including teaching the next generation of rural providers.

It has been well detailed in previous studies that retaining rural providers presents an ongoing challenge that requires a flexible and novel solution16,17. Previous studies have demonstrated that continued formal training beyond residency are critical to individual skill development, expanding scope of practice, rural placement, and clinical privileges8. This study evaluates a Fellowship program that is unique in its intention of developing a regionally grouped rural cohort that can utilize shared experience to adapt for continued success. Additionally, this study outlines a clinical financial model that provides lean but structured support. These early findings suggest that it is essential to further explore initiatives that extend training and support beyond traditional paradigms of medical school and graduate medical education to address widening gaps in geographic inequities related to limited rural healthcare access. Integration of the key elements, such as teaching and personal resiliency, that support a vibrant practice and personal meaning in medicine need to be cultivated throughout a professional career. Possible areas of growth in existing programming include increasing Fellow alumni participation, assisting with connections to specialty services, and additional support for community engagement through coaching. Recognizing that all communities are unique, this model could be applied to other health shortage areas, expanding to include other rural healthcare professions. While the Rural Fellowship is based in the USA, the program is flexible in addressing universal concepts of promoting placement and retention in rural areas where workforce needs exist. This transitional programming can be easily modeled to fit country-specific guidelines and is an important consideration for organizations interested in replicating MAHEC’s Rural Fellowship model.

Incorporation of preceptor development and mentoring skills into the Fellowship model has a potentially significant effect on building up workforce pathway programs. Since the inception of the Fellowship, the size of WNC’s rural preceptor pool has increased exponentially. This warrants further investigation as an additional area of study to expand preceptors in rural regions where, so often, it is challenging to assure viable preceptors and mentors.

This process has enabled the authors to examine future directions of the program in the WNC region and across the state. Based on early findings from MAHEC’s Rural Fellowship, the program is actively expanding in a more inter-professional direction by building relationships with clinical training programs beyond the local residency programs and making connections with practices across the region to identify the clinical sites with the greatest needs. The future vision includes cohorts of physicians, pharmacists, behavioral health specialists, advanced practice providers all learning with one another to better serve community needs. Additionally, initial conversations with other organizations across the state, including other Area Health Education Centers (AHECs) and academic schools of medicine, are exploring implementing a state-wide Rural Fellowship model. Ultimately, the primary goal for the future of the program is to diversify future cohorts and to help other rural areas implement a similar program to address healthcare workforce needs.

Despite early indications that the '6 Ps' were effectively delivered and impactful during the Fellowship year, there are some limitations owing to the length of study and the sample size. Further studies are needed to evaluate long-term retention, career satisfaction, and future resiliency of practice. A key limitation of this evaluation is the lack of longitudinal data beyond the initial years of Fellowship completion. In order to provide additional context around the impact of the Rural Fellowship, an analysis of the experience over time would clarify further which aspects of the curriculum are most meaningful and lasting. Additional monitoring of the program over time has the potential to demonstrate other secondary benefits, such as the ability to efficiently recruit and retain clinicians to rural areas, integrate them into the community environment, and groom future rural preceptors. A small sample confined to a specific region limits the generalizability of the study’s findings; however, the qualitative statements are congruent with responding to the challenges clearly outlined in existing literature12. These findings suggest promise to extrapolate to other areas and at a larger scale over time.

Conclusion

To ensure that health education and training further promote a geographically equitable workforce, innovative strategies, like the Rural Fellowship, demonstrate the potential for targeted recruitment where the greatest need exists. This cohort-based curricular model effectively addresses many of the barriers involved with initial rural placement for healthcare providers and enriches their integration into a rural community to also enhance retention.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank: Tayla Clark and Brenda Benik for figure development and graphic design; Blaise Ellery for writing support; and Lauren Payne, Bayla Ostrach, PhD, and Kathleen A. Foley, PhD for assisting in concept development and literature review efforts.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.