Introduction

Australia has one of the highest ratios of doctors per capita in the world, yet the health workforce is maldistributed1,2, with some rural areas counting 50% fewer healthcare providers per capita than urban centres3. Recruiting and retaining a high-quality rural health workforce is an unresolved global challenge4,5, and Australia is no exception1,2. Rural people account for 28% of Australia’s population, have higher and more complex health needs than the general population, yet poorer access to primary healthcare services and diminished continuity of care6,7. Geographic isolation is reported as the major disincentive for healthcare providers to work in rural Australia2,8. Stop-gap solutions such as a high rotation of short-term health staff and locums in remote parts of the country provide temporary relief, but Zhao et al argue this costly ‘quick fix’ hampers development of a thriving rural health workforce that is authentically embedded within the community9.

Primary care is the main entry point into the health system for all forms of early pregnancy care, with GPs the first point of contact for 90% of all pregnancies in Australia10. Rural women seeking health care in early pregnancy report deficits in local reproductive health services including diminished choice, lengthy wait times and significant disruption caused by the need to travel large distances at personal expense11-13. Women with unintended pregnancy also describe dissatisfaction and in some cases shock that some healthcare providers were unprepared to provide information in relation to abortion services12. A 2023 Australian Government inquiry into universal reproductive health care in Australia called the inequity of reproductive health a 'postcode lottery’14.

This article uses the words ‘woman’ or ‘women’ but the authors wish to acknowledge that girls and other people who do not identify as women – including transgender men and gender non-binary individuals – also have the capacity to experience pregnancy and may also need pregnancy options and abortion services. However, as none of these groups were mentioned by our study participants we do not refer to them directly.

Despite being fully decriminalised in all states and territories, abortion remains a ‘grey and stigmatised area of health practice, outside the purview of mainstream medicine’ (p. 5)15. Australia’s public health system does not routinely fund, provide or monitor abortion16. Most procedural (surgical) abortion services are delivered by a small number of independent providers at considerable out-of-pocket cost to the consumer13. For the past decade, only qualified GPs have been permitted to prescribe MS-2 Step, the combined misoprostol and mifepristone medication used for medication abortion up to 63 days gestation17, yet less than 10% of GPs in 2021 had undertaken the mandatory training18. Millar argues that the exclusion of abortion from the medical student curricula positions abortion as ‘exceptional’ to mainstream health19. High levels of conscientious objection to abortion provision among rural GPs support this claim20. While all conscientious objectors are legally obliged to refer to other available services, the absence of clear referral pathways or proximate options for rural populations means this obligation can easily remain unfulfilled21,22.

Little is known about how rural primary care providers, who are relied upon to deliver all primary healthcare services including abortion to local people they know22,23, manage this complexity. Previous studies in Australia have focused either on the views and experiences of rural GPs and nurses with specific expertise in sexual and reproductive health or medication abortion20,24-26, or on the experiences of consumers accessing these services27-29. Through qualitative interviews, our study aims to contribute a unique perspective. That is, the experiences of rural primary care providers who become the ‘first point of contact’ for women with unintended pregnancy and, irrespective of their knowledge, interest or expertise in abortion provision, are charged with the task of ensuring abortion-seekers reach the services they need.

Methods

This study focuses on the Western region of New South Wales (NSW), a large inland area of approximately 316,600 people dispersed across large regional cities, small towns, remote communities and on large-scale agricultural properties30. Of this population, approximately 17% are female and of reproductive age (15–44 years)30. With only one publicly advertised abortion service in this region, most inhabitants live in what Cartwright et al refer to as an ‘abortion desert’ or 160 km (100 miles) from the nearest known clinic31.

Purposive sampling was used in this study. Invitations to all 113 registered GP practices in the region, including 14 Aboriginal Medical Services, were sent in three waves, comprising a formal letter sent by post and two follow-up email reminders. The study was promoted over a 12-month period from July 2021 to July 2022 on local community noticeboard social media accounts, through the Western NSW Primary Healthcare Network, as well as through professional networks, snowballing and word of mouth. Eligibility criteria included experience supporting consumers with unintended pregnancy in a Western NSW primary healthcare setting in the previous 5 years, regardless of pregnancy outcome.

A semi-structured interview schedule was developed to explore the experiences, perceptions and roles of any primary healthcare worker providing health services for unintended pregnancies. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Inductive analysis of the data was undertaken by AN, EM and KB in two stages. Using the Framework Method32 based on Braun and Clarke’s thematic analysis methodology33, the team coded seven transcripts. An initial working thematic framework was designed by each coder independently, then compared and discussed as a team. A cohesive refined framework was then produced, which AN and EM used to recode the same seven transcripts a second time to test the salience of identified themes and make adjustments. AN then coded the remaining nine transcripts using NVivo v11 (Lumivero; https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo). A subsection of transcripts was reviewed by JT and GL to cross-check the thematic findings. Any discrepancies were discussed until consensus had been reached.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (2021/194) on 2 June 2021.

Results

Over the 12-month period, 16 participants joined the study. Eligibility was confirmed either via email or phone, and participants provided consent in writing prior to the interview or verbally at the commencement of the interview. All interviews were conducted by AN by phone call, videoconference or face-to-face. Interviews were of 35–95 minutes duration. All participants were offered an A$30 e-gift card after completing the interview in recognition of their time and contribution.

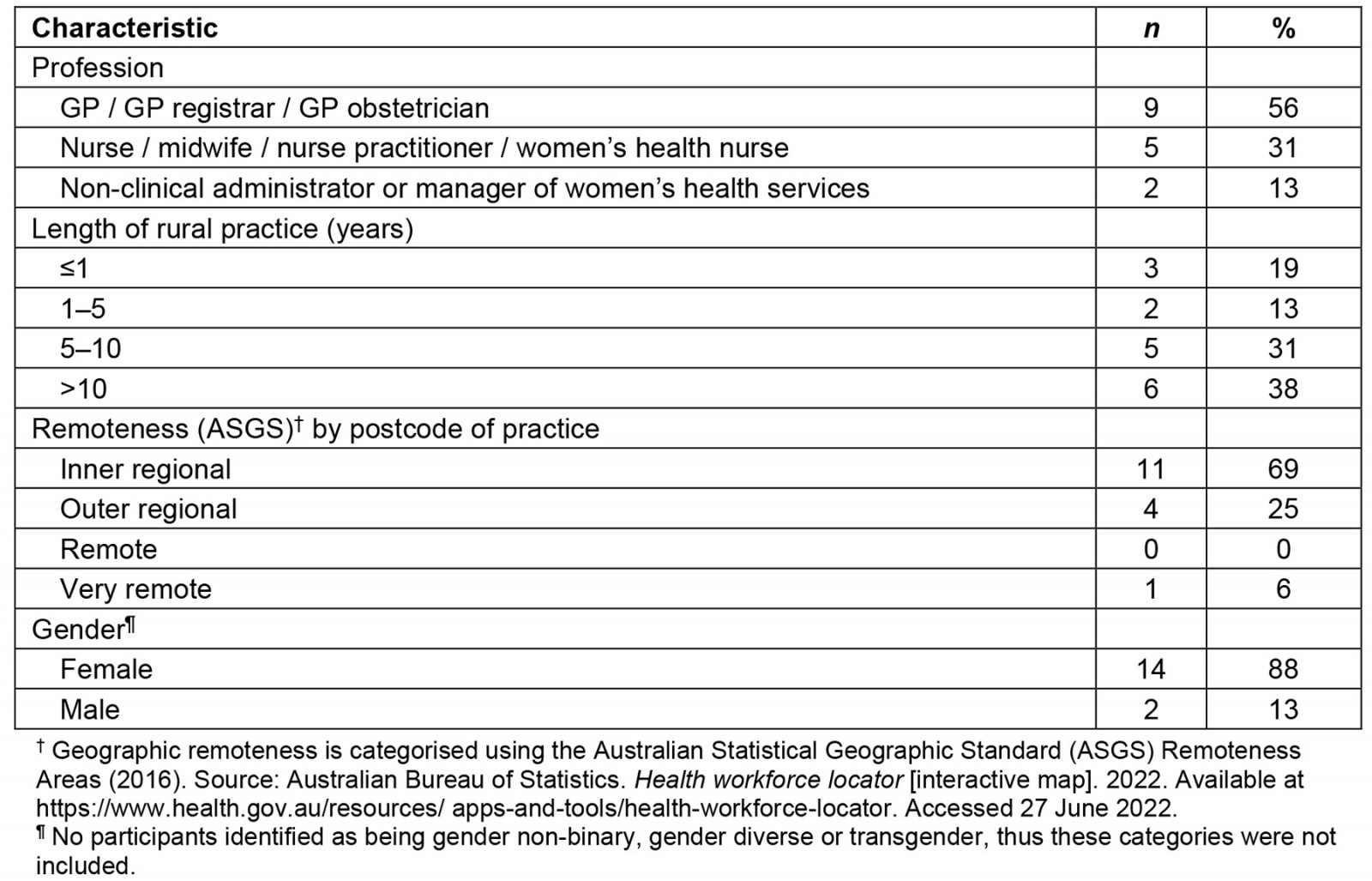

Among the nine rural GP participants, three identified during their interview as qualified to prescribe MS-2 Step. One of the three also provided procedural (surgical) abortions. Other participants included nurses and midwives, as well as frontline administrative or operational staff from women’s health and family planning services. One participant was in an Aboriginal-identified role.

Additional descriptive characteristics can be found in Table 1.

All participants agreed primary health care was the entry point into the health system for unintended pregnancy, but that local abortion services were scarce. Almost all (n=15) knew about alternative clinic-based or telehealth abortion options provided by independent service provider MSI Australia (previously known as Marie Stopes Australia), and most mentioned the sole publicly advertised abortion service in the region (n=11). None of the participants stated they held any conscientious objection to abortion, although two did acknowledge that they found discussion of abortion with consumers difficult for personal reasons.

Four main themes were identified from the data: (1) scarce abortion services place overreliance on availability and goodwill of local prescribers; (2) lack of back-up support, financial incentives and training deters providers; (3) there is interprofessional stigma, secrecy and obstruction; and (4) local abortion access requires workarounds through informal rural networks. The first theme describes how the absence of a public model of abortion care simultaneously diminishes service options and shifts the responsibility of finding referral pathways onto individual providers within an already-overburdened rural primary healthcare setting. The second theme highlights how structural limitations, including financial disincentives, and lack of education and training opportunities prevent or discourage primary healthcare workers from becoming abortion providers. The third theme describes the personal and professional challenges described by rural primary healthcare providers in navigating difficult and sometimes obstructive professional environments in relation to abortion care. The fourth theme describes how individual providers leverage their own local community networks to find ways to make abortion care available to rural consumers despite systemic barriers.

Table 1: Participants’ demographic characteristics (N=16)

Theme 1: Scarce abortion services place overreliance on availability and goodwill of local prescribers

Almost all participants spoke of difficulties of finding easily accessible local abortion services or referrals, exacerbated by the absence or conditionality of abortion provision in Western NSW public hospitals. As one participant (RPCP005) said, ‘If you’ve got a pregnancy where there’s an abnormality and what not, it’s not an issue, there are services. But there aren’t services for the on-request personal decision-making.’

This lack of public services meant redirecting all responsibility onto the small number of individual GPs trained and willing to prescribe medication abortion. As one participant (RPCP002) stated, ‘there’s only myself and one other doctor who are registered prescribers of MS-2 Step and we – to the best of our knowledge no other GPs in [major regional town] or surrounding areas prescribe it.’ Another GP explained the challenges of being the only prescriber in a large regional town but with no capacity to take on new patients:

We’re a private practice that has closed books. So unless you’re a patient of our practice who happens to see me or sees a colleague or calls reception and they’re someone who knows that I provide that service, you’ve not got a hope of seeing me. (RPCP016)

Workforce shortage and reliance on locum doctors also cause complications for the time-sensitive nature of abortion. For example, one participant (RPCP015) explained how abortion access was wholly dependent on one doctor’s schedule: ‘He’s one week on, one week off. So, a woman could be getting close to nine weeks and it’s his week off, it’s tricky.’ Another participant (RPCP008) described access to medication abortion as ‘a little bit hit and miss’ in more remote parts of the region where the service provider only visits small regional towns once a month.

The paucity of GP abortion providers also meant existing services were flooded with requests from other primary healthcare workers trying to find local options, creating tension and overwhelm. A nurse participant described a difficult conversation with a GP who had previously offered to receive abortion referrals:

He was like, ‘no, no, no, I’m not doing it anymore, I’ve got too many people, you referred too many people to me, and I was too busy, and I don’t have any support, and I’m not doing it anymore.’ (RPCP001)

A GP participant (RPCP014) said simply, ‘Demand far outstrips our ability to provide … we turn women away every week, every day.’

One participant described the deleterious effect of such a haphazard provision environment on consumers and providers alike:

The main impacts that I see are a full reception, having women who are distressed who are looking for services, and the distress that the admin staff experience by turning women away if we don’t have enough capacity to meet that demand. (RPCP008)

Theme 2: Lack of back-up support, financial incentives and training deters providers

Most participants identified the lack of back-up support from local public hospitals for any complications or additional care as a major deterrent in providing medication abortion. One GP participant (RPCP004) said encountering difficulties negotiating hospital care for a telehealth medication abortion patient experiencing complications discouraged her from becoming a prescriber: ‘If something does go wrong, who’s actually going to be able to back you up with that?’ Telehealth abortion was mentioned by almost all participants as increasing service access, especially during COVID-19, but several participants voiced concerns about the disconnect between telehealth services and local continuity of care. One participant (RPCP010) said, ‘The women are very much, I think, on their own for that and that’s why – doing it through some sort of impersonal telehealth process with someone who’s based in Sydney is just – it’s far – so far from ideal.’

Some participants described a tension between the financial modelling of GP private practice, the time required to deliver quality medication abortion services including counselling and the lack of government subsidisation for this. One participant described this in the following way:

Having specific item numbers that remunerate practitioners appropriately for providing this service might reduce gap for fees or allow bulk billing to be actually financially viable for these sorts of services to increase relative access. (RPCP016)

For another participant, this tension prevented them from offering services altogether, as they felt unable to deliver thorough care under a time-based financial billing model that favoured short consultations:

If you come to somebody like me, I’m willing to spend the 40 minutes with you, but I can’t do that for Medicare funding because if I do that for Medicare funding, then I’m earning a third or half of what the guy next door is earning … I used to be prepared to do that but I’m not anymore. (RPCP013)

One participant (RPCP010) acknowledged their workplace absorbed a financial loss to ensure service accessibility and quality of care to consumers: ‘We book long appointments here. That’s intentional … We charge low rates ... We don’t obstruct access to services, so payment is the least of their worry.’

This arrangement relied upon the generosity of the collaborating GP prescriber: ‘Obviously, we’re also relying on the extreme goodwill of our wonderful GP who is happy to work for a percentage of Medicare.’

Yet another participant suggested a Medicare-funded service model could also prevent unnecessary costs to the broader health system in the long term:

One of the things we don’t take into account is the cost of the state or the country looking after a child who was never wanted and the cost to that child who knows that … it’s actually saving the taxpayer a hell of a lot of money down the track. (RPCP005)

Almost all GP participants mentioned the absence or optionality of abortion education within their medical curriculum.

One participant (RPCP013) described dismay when a tertiary institution requested censorship of education about abortion services during student clinical placements: ‘How dare a university try and interfere with the clinical services we provide in our tiny country town to our women who are often quite disadvantaged socioeconomically.’

The unwillingness to provide clinical training or supervision for abortion was also cited as a problem by more than one participant. One GP participant (RPCP004) said, ‘I know the supervisor in our practice, she’s quite religious and I can imagine that that could be a challenging discussion to have as a junior registrar.’

Another GP shared this view:

Doctors who have an ethical, moral objection to contraception services or termination of service – termination of pregnancy services, I am 100 per cent sure that 99 per cent of them won’t make arrangements for their registrar to receive that education from somebody else. (RPCP013)

Theme 3: Interprofessional stigma, secrecy and obstruction

All participants described experiencing opposition to abortion from other medical professionals, ranging from passive disinterest to proactive obstruction.

Abortion stigma and obstruction were described by more than one participant as directly related to the power structures within hospital management. One participant (RPCP003) said, ‘the problem is that you do have a number of conscientious objectors in the hierarchy of these larger hospitals … that is going to be super hard to get past, because they're the people that make the rules.’

Most participants also identified interprofessional stigma among colleagues as yet another reason why abortion services were both limited and not advertised. One participant said the issue was the following:

Being judged by your fellow peers. I know someone who does that but it’s still on the quiet. It’s still a personal conversation you have that they’re happy to do it. But it’s not – no one stands up and says, right, I’m offering this service. (RPCP007)

Another participant (RPCP014) described this sense of secrecy in the following way: ‘Oh you know it’s kind of whispered in corridors, like who – do you know anyone who does abortions?’

A junior GP (RPCP016) described frustrations at the lack of open communication among GPs about where services were available, describing an incident where a consumer lost valuable time searching for abortion providers: ‘They’d seen one or two or three GPs before getting in with the right person ... and actually getting started with the service that they’re requesting.’

For some participants, the unwillingness of providers to openly share information about where medication abortion could be prescribed or dispensed meant they spend considerable clinical time searching for answers. One participant explained this in the following way:

I spend more time ringing pharmacies, looking at Google Maps trying to figure out where they are, where the pharmacy is. Then I have to call the pharmacies and see if they will … dispense it, and … if they will, how long it will take to get it. Then call the patient back with that information so then we can make a plan [about dates]. I might have to call five or six pharmacies before I find one that will dispense. (RPCP014)

Such unclear pathways complicate the timely location of available services for consumers and primary care workers alike, and consequently limit choice. As one participant said, (RPCP004) ‘when it takes three or four weeks to get into an appointment with the doctor, that can be another barrier, that by the time you get there … you're too late to have a medical termination.’

Participants frequently cited negative ramifications in a small-town context as a reason why local health providers were not willing to become medication abortion prescribers or advertise their services, making them harder to find. One participant (RPCP003) described becoming known as the local abortion provider was ‘quite tricky’ for the individual’s quality of life in a small community, stating, ‘that doesn't bode well for them staying in the community either.’

Even reproductive health specialists were reported as refraining from publicising their services. As one participant (RPCP001) said, ‘There's no advertising at all about this gynaecologist, obstetrician/gynaecologist that provides this service. If you googled him, it wouldn’t be on his website. It's just like this underground service that he provides.’

A participant working at the only clinic publicly offering abortion services in the region said acceptance of abortion within the workplace enabled productive discussion among peers, but acknowledged this was rare:

Within [regional clinic] we have lots of collegiate support between each other. We spend a lot of time talking about, oh you know this imaging provider did something really dodgy and so don’t use them, and whatever. We’re all very open about it and it doesn’t feel underground. (RPCP014)

Theme 4: Local abortion access requires workarounds through informal rural networks

Many participants in this study described using their own interprofessional and personal networks within the rural community to devise informal abortion access. Speaking generally, one participant (RPCP001) said, ‘You need to know the right people; you need to know the contacts. You need to know who to ask. It's sort of like the back little alleyways to access those services.’

One GP participant (RPCP013), although not a medication abortion prescriber, regularly saw women seeking these services and relied upon a trusted colleague for help:

I work with him, his room is next door to me, so I can go and bang on the door and say I really need a favour, but if you're a woman who's ringing from [regional city] and speaking to our receptionist, all they're going to say to you is, well, his next appointment is in eight weeks' time.

One nurse participant (RPCP011) said that their longstanding role as a women’s health practitioner meant that women within the community entrusted information about available abortion services, which could then be used as an informal directory: ‘It was through having a conversation with both her and her mother that I found out it was this female GP in another township is a prescriber of medical termination. So, I grabbed that name too.’

Other participants shared stories of using their multiple roles within the health system to develop informal referral pathways for abortion. For example, one participant (RPCP002) explained:

It’s quite convenient because in [regional town], if a patient has an issue and they contact me, then I can admit them under my care at the hospital. Whereas if something happens and they need to access care and I haven’t got admitting rights at a local hospital, then I’m relying on another service to pick them up.

Another participant (RPCP005) described a similar situation, saying:

Now, it might be your hospital week, but if the person that needs to see you isn’t comfortable going there and will only see you at the AMS [Aboriginal Medical Service], we will organise a time to meet them there to actually see them, and vice versa.

One nurse participant (RPCP015) shared yet another effective informal referral pathway involving collaboration and task-sharing between a nurse-led women’s health service and an interstate GP, whereby consumers sought services from the women’s health clinic, the GP prescribed medication abortion via telehealth within the clinic setting and the nurse undertook all pre- and post-abortion care. The participant described this ‘workaround’ as necessary because, ‘We realised that that service was kind of non-existent anymore because a lot of conscientious objections in [remote town].’ The participant went on to explain that perceptions within workplace management that abortions should only be provided by specialists (not through collaborations with private practice GPs) ultimately ended the service: ‘So that was working well for two years, and we got a new medical director, and he axed it.’

Several participants said it was the strong community ties that motivate local providers to go the extra step to help. One participant (RPCP011) said, ‘It has to be local. It has to have those people who know those townships, those communities, they know the needs, they've seen it, they've heard it, and they feel it themselves too.’

Another participant (RPCP013) praised the work of local colleagues but acknowledged workarounds were time intensive, extra work and too dependent on the goodwill of individuals: ‘Imagine how much better it would be if we had an actual service ...’

Discussion

This study explores the experiences of 16 primary healthcare workers who provided ‘first contact’ health services for unintended pregnancy in Western NSW in the previous 5 years. All participants, irrespective of their role or scope of practice, described their confidence and willingness to provide early pregnancy counselling and decision-making support. However, almost all also described multiple, complex and often intersecting barriers to their provision of or referral to local abortion services.

Our study findings highlight the multiple pressures of a rural primary healthcare system in workforce crisis, the incompatibility of medication abortion with GP financial modelling and appointment scheduling and, perhaps most pertinent of all, the professional politics involved with trying to deliver a historically stigmatised reproductive health service without adequate support from the public health system. The way in which these pressures and responsibilities coalesce in the lived experience of rural ‘frontline’ health providers is the focus of this article. As each of the four identified themes in this study illustrate, the availability of abortion services in rural primary care settings is dependent on the motivation of individual primary care providers to persist against a system that is either unwilling or unequipped to integrate abortion into routine healthcare practice, sometimes to their own financial, personal or professional detriment.

Our study design centralised the experiences of rural primary healthcare providers trying to overcome the dual challenges of rural health systemic deficiencies and broader abortion exceptionalism in Australia to ensure abortion services are accessible to their communities. The impact of abortion restrictions and obstructions on the lives of rural primary care providers is a focus rarely seen in literature on abortion services worldwide34. Yet solutions to sustaining and increasing abortion access in rural communities will need to directly address the multiple administrative, financial, reputational deterrents these individuals face, and the burden imposed on those who continue regardless.

Previous Australian studies have highlighted the limitations of a medicalised model of abortion16 in a system that is overregulated, out of step with current international models of care and yet to integrate abortion into mainstream healthcare35. The consequences for rural people experiencing difficulties accessing abortion care in Australia have been well documented13,14,29,36,37. Recent research with rural primary healthcare providers in Australia has focused on the experiences or views of those with a specific interest in or willingness to prescribe medication abortion20,24-26,38-42. Even among this motivated group, low uptake of medication abortion training, fears of managing service demand, lack of local support and potential collegial dissent, as well as the general capabilities of the rural health system, were reported as the major ongoing challenges20,24-26,38-40.

One of the strengths of this study is its deliberate recruitment of a wide range of participants working in rural primary healthcare with a range of interest and expertise in abortion. This not only includes GPs, but also nurses, midwives and women’s health clinic administrative staff whose experiences highlight the complexities of negotiating abortion access, including for those working within the health system. The geographic specificity of this study is also important in this context. Western NSW is the largest region and ‘abortion desert’ in the state, and is facing a severe GP shortage, with the local primary health network projecting a quarter of the region’s population are at risk of not having a GP practising in those communities over the next 10 years43. Nurses across the region have also repeatedly described the nursing shortage as ‘dangerously unsafe’ to patients and escalating burnout for those working on the ground 44.

Australia’s National Women’s Health Strategy 2020–2030 lists maternal, sexual and reproductive health as its first priority, acknowledging ‘the need for women and girls to be informed of, and to have access to, safe, effective, affordable and acceptable forms of fertility regulation, health services and support’ (p. 22)45. Yet there was a stark absence of any indication of future national policy, funding or plans for universal, free public abortion in the recently released Senate Inquiry report 14.

The Australian Government’s ongoing resistance to integrating abortion into its public health system, or to providing adequate subsidisation through the Medicare health insurance scheme, shifts the responsibility to provide and manage the cost of abortion services onto primary care. Tomnay argues this leaves many primary care providers inadequately remunerated, running at a financial loss or unable to afford to provide these services46. The consequential impact on rural abortion access is clear – the country’s largest independent abortion provider MSI Australia stated the justification for the closure of four of its regionally based abortion clinics was that they were simply ‘financially untenable’47.

In July 2023, Australia’s pharmaceutical regulator, the Therapeutic Goods Administration, removed requirements for GPs to train and register as medication abortion providers48. While some abortion advocates have described this policy shift as a solution to increasing prescriber numbers, especially outside urban centres40,49, this study countercalls for greater consideration of the rural context. Our findings highlight how the paucity of rural abortion services and referral pathways already places undue pressure on individual rural GPs to forego income, risk reputational damage and uncertainty of back-up support, simply to ensure local rural services are available. That participants in this study continued to do this work is not indicative of a solution, but rather reflects individuals taking on the burden of responsibility instead of and in spite of the system. The personal impact on these practitioners, whose individual views are in conflict with the institutional structures they represent, is described by Chowdhary et al in a similar USA-based study of abortion providers as the ‘sustained burden of identity negotiation in highly stigmatized environments’ (p. 1355)34. As our findings demonstrate, such a burden is often unsustainable.

Nurse-led models of abortion care are one workforce-strengthening strategy that is already in an exploratory phase in Australia50. Benefits of this approach include alleviating demand on GPs and empowering nurses to extend their scope of practice and, consequently, enabling greater medical abortion access for rural populations51,52. Yet as Carson et al explain in a recently published study of nurse-led abortion in similar rural settings where abortion is publicly funded in Canada, ‘the optimism about the potential for abortion to become more accessible for people in rural and remote areas is challenged by ongoing resources issues, a lack of health professionals in the local community, and perceived stigma in some smaller communities’ (p. 17)53. Limited availability of ultrasound services, the need for pharmacies willing to stock abortion medication as well as proximate emergency services for back-up support were three reasons why Carson et al suggest such optimism overlooked the realities of rural primary care53. Ironically, abortion provision within rural public hospitals would instantly resolve each of these concerns and provide a clear pathway for services in rural Australia. Any proposed solution that implores the primary healthcare workforce to shoulder more responsibility also simultaneously permits the ongoing obfuscation of responsibility of the Australian public health system.

This study has limitations. The findings of this study are reflective of the experiences of primary care workers in one specific area of rural Australia and may not be generalisable to other parts of Australia or to other rural contexts. Our recruitment strategy sought participants with experience supporting people with unintended pregnancy, and, while abortion was not specifically stated, no conscientious objectors were recruited, suggesting potential selection bias. The study recruitment period also coincided with Australia’s first large scale COVID-19 vaccination program, which directly impacted the primary healthcare workforce workloads across the Western NSW region. As such, some GP practices did indicate to the research team that, while interested and supportive of this study, they were simply too overwhelmed to participate in research during this unprecedented time.

Conclusion

Improving rural abortion access in Australia is contingent on solutions that address the unique barriers, disincentives and competing burdens experienced by the rural primary healthcare workforce on top of a pervasive culture of abortion exceptionalism nationwide.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the rural primary healthcare workers who participated in this study for their generosity of time and support of research particularly during a global pandemic.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.