The problem

In December 2018, the National Rural Health Commissioner presented the Australian Government Minister for Regional Health with advice on the formation of a National Rural Generalist Pathway (NRGP)1 outlining selection, training and employment strategies required for a sustainable and fit-for-purpose medical workforce for rural Australia2.

Despite this policy statement, small rural communities across Australia continue to grapple with a chronic shortage of healthcare professionals, particularly medical personnel3,4.

So, is it possible to implement the NRGP and, if it is, will it work?

Decades of government and professional efforts5,6 – including medical school rural quotas, bonded medical placements, rural scholarships, rural clinical schools, regional training hubs, rural intern rotations from city hospitals, rural general practice training rotations, recruitment of international medical graduates and unsustainable financial incentives – did not solve these workforce shortages7,8.

Why should this NRGP policy be any different?

These are the questions that the Riverland Academy of Clinical Excellence (RACE) sought to answer.

The context

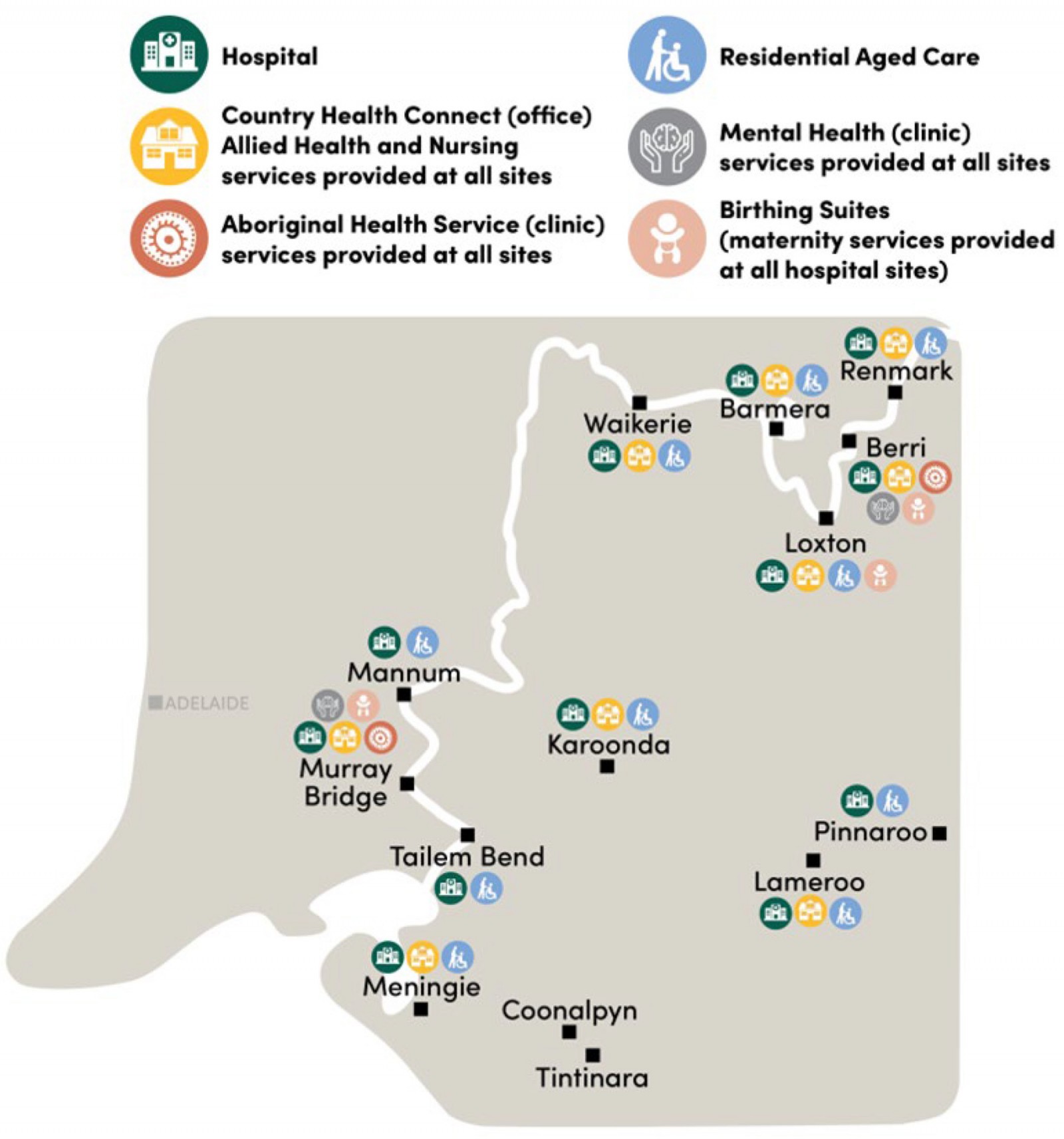

The Riverland Mallee Coorong Local Health Network (LHN) serves a population of 70,000 people across 12 rural towns in South Australia (Fig1). These towns each have a hospital and general practice. The hospitals vary in size, ranging between 4 and 50 acute beds, with 10 towns accommodating between 10 and 90 aged care beds. The Riverland Mallee Coorong LHN also provides community-based allied health, nursing and mental health services because there is acknowledged market failure of the private sector for these services. In 2019 there were approximately 100 doctors across the region. One hospital, in the small rural town (Modified Monash Model 5) of Berri, had a mix of GP contractors and some non-GP specialist salaried medical staff. In the other 11 sites the local GPs were engaged as contractors through a fee-for-service model.

All the general practices had been chronically understaffed for many years, which was further compounded by the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Challenges were exacerbated by the closure of national and state borders, severely limiting international recruitment.

Figure 1: Map of Riverland Mallee Coorong Local Health Network region.

Figure 1: Map of Riverland Mallee Coorong Local Health Network region.

The strategy

In 2021, the Riverland Mallee Coorong LHN created RACE9,10 as a vehicle for the principles of the NRGP. RACE aims to transform the region into an academic health science network11 and was designed to signal its intent to embrace the responsibility of training its own workforce, contribute to a robust evidence-based healthcare framework and provide excellence in care that the rural communities rightfully deserve. Initially focusing on medicine, which faced the most immediate crisis, RACE has since broadened its scope to encompass all facets of the LHN, including allied health, mental health, nursing and midwifery, and leadership development.

The outcomes

In two years, RACE has created transformation within the Riverland Mallee Coorong LHN, starting from the ground up and achieving accreditations for all the postgraduate training required from intern to Rural Generalist Fellowship. RACE has already recruited more than 30 new doctors to live and work in these rural communities and train for a Rural Generalist Fellowship; this number will rise to more than 40 by February 2025. This process has fostered a substantial increase of over 25% in the region’s medical workforce. To support the education and training of clinicians, RACE has developed a research unit, thus creating employment opportunities for rural and remote researchers. Albeit in its infancy, the local chief investigators have been successful on nine nationally competitive grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council and Medical Research Future Fund. There have been 17 publications and 20 international and national conference presentations with RACE clinicians and researchers as authors.

The tactics

Learn from and acknowledge local Aboriginal wisdom

First Nations Peoples offer a profound perspective on health and wellbeing. Central to this worldview is the spiritual connection to their ancestral lands, or 'country'. Complementing this with the conventional western model creates a holistic biopsychosociospiritual understanding12. This synergy holds significant value as it serves as a meaningful framework for individuals contemplating a career in medicine, emphasising the intrinsic importance of community and cultural ties. The places in which we were raised, the locations of our families and the communities we belong to profoundly influence our career choices. Historically, this dynamic has disadvantaged rural communities, as the production of healthcare professionals has been predominantly centralised in urban areas13. By deliberately shifting the approach within RACE to focus on cultivating local talent, this ancient wisdom is harnessed to empower and sustain local communities.

Never waste a crisis

The region has faced numerous medical crises. In each instance, when a small clinical team ‘fell over’ due to an unsustainable or unviable staffing model, the approach taken has simultaneously laid the groundwork for a sustainable future workforce while addressing the immediate crisis. This proactive stance prioritised the development of the region’s capacity to train its own rural generalists rather than persisting with outdated and ineffective strategies centred around recruiting externally trained doctors at any cost.

Change the narrative

The Riverland Mallee Coorong LHN established RACE to be distinguished by its commitment to fostering excellence in health care rather than merely serving as a last resort for those unable to secure positions elsewhere. RACE’s philosophy is clear: we do not use behaviourist drivers, such as inflated remuneration, but instead base our selection solely on merit – those deemed proficient and capable are invited to join a community dedicated to advancing clinical standards and practices.

RACE has been so successful at changing the narrative that many of our more experienced clinicians, who had become disillusioned with their previous experience of our services, have again joined us to become clinical supervisors and mentors, embracing the opportunity to be meaningfully engaged in a culture of excellence in rural health care. This meaningfulness is an important factor in motivating healthcare professionals for rural regions14.

Shear the whole sheep

The NRGP delineates essential components2: the selection of local students or those with ties to the region, a steadfast commitment to excellence, immersive local education from high school through to Rural Generalist Fellowship and the provision of supportive, meaningful employment opportunities. Despite well-intentioned efforts, and despite international evidence that comprehensive approaches are required for success15-17, previous workforce policies in Australia have implemented only fragmented segments of this pathway, perpetuating the ongoing crisis. This piecemeal approach is akin to shearing only half of a sheep and expecting it to remain healthy throughout its life. Recognising a need for comprehensive action, RACE decided to implement the pathway components as a whole. While some elements were already in place, such as hosting one year of Flinders University18 medical school training in the region and hosting a small number of GP registrars in the private practices, critical gaps persisted. We lacked influence over student and registrar selection, cohesion between training levels and a reputation for high-quality regional jobs, and we faced disengaged doctors disillusioned by the limited prospects for new colleagues in their practices.

Our initial focus was on addressing these deficiencies. We created salaried positions in one of our hospitals, jointly led by rural generalists and relevant other specialists tasked with facilitating junior doctor and advanced skills training, in addition to providing direct patient care. A medical education unit was formed, governed by a medical education committee and RACE Partnerships Council. It involved relevant internal and external stakeholders – including students, trainees, public and private practice supervisors and international experts – and created rotations for junior doctors that leveraged our strengths, met accreditation standards and enabled comprehensive junior doctor training in our region. Responding to concerns raised by junior doctors regarding job security, and the terms and conditions in GP training, we offered our interns 5-year contracts. Initially, the LHN wore the financial risk associated with offering 5-year contracts; however, the advent of the Single Employer Model19 and access to the John Flynn Prevocational Doctor Program20 has provided a stable framework for their training across local hospitals and private GP practices, fostering confidence in planning their careers and integration into the community (to be part of the ‘country’). We also prioritised support for clinicians undertaking research, teaching and personal development, ensuring they could take leave as needed to recharge. A dedicated research team was appointed to assist clinicians with research and quality improvement audits. Furthermore, we instituted initiatives such as grand rounds, journal clubs, leadership courses, one-on-one mentoring, and professional development skills conferences. Some areas still require attention, but the overall health of the ‘flock’ of medical staff has significantly improved, which is a testament to our comprehensive approach.

Ensure external critique

The landscape of health service and educational reform is strewn with well-intentioned initiatives that often go unscrutinised, lacking critical evaluation or exploration to extract valuable insights and knowledge. Recognising the importance of rigorous examination, RACE has proactively sought an external partner to evaluate, examine and enhance our research capabilities. After a thorough tender process, Flinders University emerged as the chosen collaborator, and we eagerly anticipate the results of this collaboration.

Conclusion

We have outlined the strategy and tactics employed by the Riverland Mallee Coorong LHN to address enduring medical workforce challenges. It appears that the NRGP can be implemented with success for both hospital and general practice medical workforces.

Rather than waiting for support from others, the LHN has adopted a proactive approach from within its own financial and human resources, transitioning from outsourcing its supply chain of medical workforce to vertically integrating the production requirements for its medical workforce. There is still considerable work ahead to ensure long-term sustainability, and further research is required into the change management, workforce, pedagogic and economic aspects of the pathway, but the initial outcomes appear transformational within only 2 years. The expansion of the medical workforce by 25% has re-engaged and reinvigorated the existing workforce, enabled new models of care, brought fresh ideas, perspectives and talent into the region, and instilled a renewed sense of optimism for our collective future.

Not only has the health service’s medical workforce thrived, but general practice is also thriving due to the integrated, multidisciplinary nature of rural generalist training and the broad scope of practice of a well-trained rural generalist workforce.