Context

Honourable history

In Norway, rural public health doctors have a long and honourable history dating back to 1603 when the first doctor was employed by the state as a regional medical officer in Western Norway. Government employment of rural doctors then continued for almost 400 years until 1984. During the twentieth century, and particularly after World War II, hospital specialists have gradually overtaken the leadership and influence of their rural colleagues. The Municipality Health Act 1984 compounded this when it determined that the main employer of rural doctors should be the municipality, rather than the state.

Centralisation and rural deprivation

In Norway, as in other western countries, the trend in the health service system has been towards urbanization and rural deprivation. Since 2000 the Norwegian transformation of specialist health care, including hospitals, into state enterprises has contributed to increasing centralization of the medical workforce, at the expense of services to rural and remote areas. This has happened despite Norway's inclusion in the group of European countries with an agreement to support a decentralised population. Although the Norwegian Government has supported certain initiatives (eg tutorial groups for residents) to stimulate recruitment and retention of rural and remote health workers, the challenges described by WONCA 1 before 2000 remain:

The world wide shortage of rural family doctors contributes directly to the difficulties with providing adequate medical care in rural areas in both developed and less developed countries. WONCA believes that there is an urgent need to implement strategies to educate, recruit and support sufficient numbers of skilled rural family doctors to provide the necessary services.

In all rural and remote Norwegian municipalities there has been population reduction in each of the last 10 years2. During the same period there has been an increasing instability among GPs in small and remote municipalities3, resulting in a distinct reduction in opportunities for medical student and intern placements. At the University of Tromsø, where the rural placement of medical students has been a core element of the curriculum since the founding of the medical school in 19734, this unprecedented situation is impacting on the quality of medical education.

Foundation of an academic centre for rural medicine

In 1999 the University of Tromsø's proposed project strategies to stimulate teaching, research and networking among rural practitioners were approved and financed by the Ministry of Health. Initially based in the north, the projects have developed into nationwide activity, culminating in the designation of the National Centre of Rural Medicine (NCRM) in Tromsø as the permanent Norwegian academic centre for rural practice from 2007 (Figs1,2). Today the centre is funded and professionally supported by three partners: the Norwegian Directorate of Social and Health Affairs; Health North (the state corporation for specialist health services in the northern region); and the University of Tromsø. The funding of the NCRM acknowledges the failure of economic incentives and government campaigns to motivate young doctors to choose a rural career, even under optimal economic and political conditions.

Figure 1: Map showing the location of Norway in northern Europe.

Figure 2: Tromsø: the home of the National Centre of Rural Medicine in Norway.

Issue

The NCRM was dedicated to examining both common and diverse expressions and values of rural practice, and to use this insight and knowledge to revitalise and strengthen the health care provided to rural-living populations. A key challenge for the NCRM is to identify factors that influence young doctors to choose rural careers. This article presents and discusses the NCRM's main aims and achievements to date.

Aims

The NCRM has three main aims. The first and principal aim is to bridge the gap between the academy and rural medical practice. The second operational aim is to promote research, education and networking among rural health professionals. The third political aim is to contribute to recruitment, stability and quality in rural health care.

The principal aim implies that rural medical practice - what is expected from the rural family doctor and how he/she actually delivers it - needs to be investigated, described and interpreted. Bridging the gap between practice and the academy specifically means integrating the rural perspective into medical theory and the body of medical knowledge. The operational aim is the core activity, fundamental to the academic centre, thereby contributing to the other two aims. The NCRM's political aim depends on coordinated work to promote empirical and research-based evidence aimed at improving rural practice and health care, and influencing relevant bodies to provide appropriate resources.

Achievements

Among a variety of activities and achievements, three will be discussed. The first is a book, which has encouraged a national collegial discussion about the concept and nature of rural medicine. The second is a professional development and research program that has consolidated the basis from which to continue the NCRM. The third is an innovation of networking and meeting places for rural doctors - primarily national but also international - aimed at enhancing opportunities to share experience, build theory and discuss professional development issues.

Published descriptions and distinctions of rural medicine: This 2005 Norwegian language book (English title: 'Between nostalgia and avant-garde - rural medicine in modern times') consists of 13 essays5. Among these, five concern historical and theoretical perspectives of rural medicine, and the remaining eight are based on rural GPs' experiences and stories from their own practice. The book created considerable discussion among the Norwegian medical establishment. The editors' declared intention was to be open to various interpretations of rural medicine, rather than narrowing the concept of rural medicine to any particular tradition. Among the criticism, one academic criticised the book as being imbalanced to the point of nostalgia and ideology, and so inappropriately addressing today's rural health challenges6.

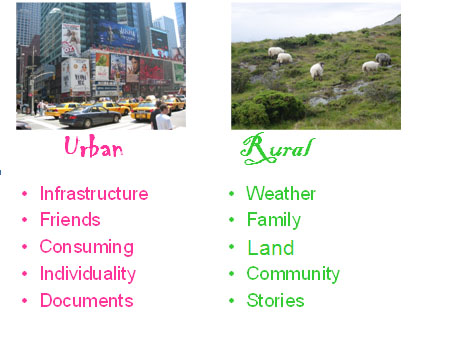

In 2007 the NCRM arranged a workshop with international narrative medicine scholar Professor Rita Charon7 at Columbia University, New York, to explore rural medicine perspectives. In support of the NCRM publication, the workshop endorsed the common experience in the 'stories of illness' shared by this expert and rural practitioners, and the fundamental value of narrative as providing examples of good clinical performance. In rural practice, narratives related to illness, family, culture, context and life history often contain information crucial to appropriate patient-centred understanding and decision-making. This corresponds to the common features of rural living, which are highly relevant to the rural doctor. Based on lifelong experience as a rural GP, and in accordance with the diverse perspectives of the NCRM book, one of the authors of this article [ES] has identified some comparative dimensions that describe key differences between urban and rural determinants and values (Fig3). Subsequent workshop and educational discussions in a variety of settings suggest these differences are consistent with the general views of doctors and medical students in Norway and other European countries.

Figure 3: Summary of key differences between urban and rural determinants and values.

Professional development and research: The NCRM Program for professional development and research was one of the initial joint projects of the University of Tromsø and the Ministry of Health. Launched in 1999, its aim was to stimulate quality improvement and research among rural GPs. Since its inception, the program has supported approximately 50 minor projects run by GPs, either alone or with other local health professionals. Among these, seven projects have expanded into major PhD research, constituting a varied portfolio of themes:

- A hermeneutical approach to understanding rural practice.

- Communication and understanding the risks of medical decision-making.

- The workload, work content, and the interaction of public health physicians in Norway.

- Medical leadership in rural practice.

- The role and tasks of the doctor in emergency teamwork.

- Care of people suffering from dementia in northern rural practices.

- The use of hospital specialist services from different municipalities.

Based on this, the NCRM has established a PhD research group among rural GPs. The group meets on a regular basis for mutual guidance and feedback, with participants granted part-time appointments to the centre to enhance their ability to combine research with clinical work.

Research strategy In the beginning, NCRM research strategy was simply to support and motivate individual initiatives among GPs; however, two main thematic areas are on the future agenda. The first is to investigate and describe aspects of rural practice; and the second, to explore the specific challenges of and possibilities for shared care between rural-based practitioners and hospital-based specialists. We believe the latter concern to be of particular importance in Norway where primary health care and hospital care function as separate enterprises, both economically and professionally. The rising hospital costs of many years have now reached enormous heights and are practically out of control. The logical solution is to promote shared care and allocate more resources (money, manpower, education and research) to developing primary and rural health care8.

Networking: The third main achievement of NCRM is creation of meeting places for and networking among rural practitioners and academics. Over the years the centre has promoted this by arranging annual national conferences on rural medicine, along with offering a virtual 'rural doctor meeting space' on the website. The NCRM has also brought the Norwegian discussion to an international agenda on several occasions by its participation in the European Rural and Isolated Practitioners Association (EURIPA) and in two workshops on 'Defining and describing rural medicine' (WONCA World Rural Conference, Santiago de Compostela, 2003; and WONCA Europe Conference, Paris, 2007). Other international initiatives include involvement in a student rural placement exchange, and contribution to an internationally renowned film on doctor-patient communication in a rural community9.

Nationally, the networking activities have been essential to NCRM achievements to date, and the future intention is to serve as a home base, a meeting place and an arena for development and debate. Internationally, the NCRM has been restrained by a language barrier, for few Norwegian patients, especially those who are elderly, speak English and this limits participation in the exchange of students among rural practices. In addition the NCRM website is still under development and does not yet have an English version. However, in the meantime, many Norwegian students and doctors are fluent in English, and are interested and involved in international networking activities.

Conclusion

The existence of a rural medical academy is crucial for long-term recruitment to and retention of the rural medical workforce, and also to maintain a balance between community- and hospital-based services. It is also important to convert rural doctors' experience into theory for the further development of medical knowledge and health care. Considering its achievements to date, the NCRM has made a favourable start to building a bridge between rural practice and the medical academy in Norway.

References

1. WONCA. Rural practice and rural health. (Online) 1999. Available: http://www.globalfamilydoctor.com/aboutWonca/working_groups/rural_training/practice/Practi_t.htm (Accessed 5 June 2008).

2. Statistisk sentralbyrå [Statistics Norway]. Fortsatt sentralisering [Continuing centralization]. (Online) 2007. Available: http://www.ssb.no/vis/emner/00/01/20/valgaktuelt/art-2007-08-30-01.html (Accessed 30 August 2007). [In Norwegian]

3. Andersen F, Forsdahl A, Herder O, Aaraas IJ. Legemangelen I distriktene - nordnorske funn, nasjonale utfordringer [Lack of doctors in rural districts - the situation in Northern Norway]. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2001; 121: 2732-2735. (In Norwegian)

4. Knutsen SF, Johnsen R, Forsdahl A. Practical training of medical students in community medicine. Eight years experience from the University of Tromsø. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care 1986; 4: 109-114.

5. Lian OS, Merok E (Eds). Mellom nostalgi og avantgarde. Distriktsmedisinen i moderne tid. Kristiansand: Høyskoleforlaget, 2005. (In Norwegian)

6. Hunskår S. Fri oss fra den nye distriktsmedisinen. [Free us from the new rural medicine!] Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2005; 125: 1879. (In Norwegian)

7. Charon R. Narrative medicine. Honoring the stories of illness. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

8. Macinko J, Starfield B, Shi L. The contribution of primary care systems to health outcomes within Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, 1970-1998. Health Services Research 2003; 38(3): 831-865.

9. Swensen E. Et hermeneutisk ballespark [Interview with Eivind Gustav Olsen Merok]. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2005; 125: 3304-3305. (In Norwegian)