Introduction

Rehabilitation is primarily an 'educational problem-solving process'1,p814 of adjustment in response to injury or illness that is experienced and owned by the patient2,3. Rehabilitation services as we know them today originated during the World War II and were aimed at returning injured servicemen to active duty4. More recently, target populations have broadened to include many more diagnostic categories5. This is because rehabilitation increases quality of life by enhancing the ability of patients to undertake the activities of life, that is, to function at the 'person level'.

In Australia and internationally there is a growing appreciation of the contribution of rehabilitation services to quality of life for people with a range of conditions. For an increasing number of patients in a widening range of diagnostic categories, rehabilitation is 'the link'6,p.226 or 'the glue'5,p.S52 between acute care and the community. As such, rehabilitation is central to the effectiveness of the whole healthcare system.

In New South Wales (NSW) , Australia, specialised rehabilitation services support persons to reclaim self-care through the provision of 'medical rehabilitation' services7 which involve:

- the prevention and reduction of functional loss

- the limitation of restrictions of activity and participation arising from impairments

- the management of disability in physical, psychosocial and vocational dimensions

- improvements in function 5,p.S31.

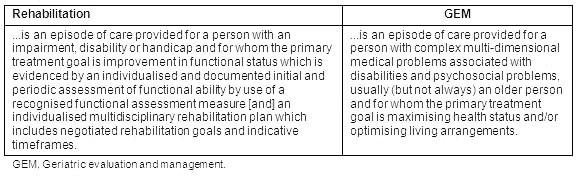

Of relevance to this study are the NSW Department of Health patient classifications, 'rehabilitation' and 'GEM' (geriatric evaluation and management), which are defined in Table 1. Patients in both these classifications receive rehabilitation services.

Table 1: Definitions of rehabilitation and geriatric evaluation and management patient classifications in New South Wales8

In NSW, most specialist medical rehabilitation services are in metropolitan or large regional centres. This suggests that many rural dwellers are either hospitalised a long distance from home for inpatient rehabilitation, or do not have access to such services.

Being hospitalised for rehabilitation away from one's home is far from ideal. Conversely, the provision of rehabilitation services close to home makes an important contribution to patient rehabilitation by facilitating interaction between patients and their communities. If family and friends have shorter distances to travel they are likely to visit more frequently. More visits means more support for patients during adjustment to their altered circumstances. More visits also help family and friends to adjust. This support is valuable for patients not only during their 'formal' rehabilitation, but also during post-discharge rehabilitation as they re-integrate into their communities, often with a newly acquired disability.

This article reports on a project that studied the expansion of specialist rehabilitation services in rural NSW.

The study

Aim: The aim of this project was to study the expansion of specialist rehabilitation services in central NSW through the introduction of rehabilitation as a new service type at 2 small rural multi-casemix hospitals, within an integrated area-wide model of rehabilitation service delivery.

The expansion of specialist rehabilitation services in central NSW: The expansion of specialist rehabilitation services in central NSW involved the introduction of rehabilitation as a new service type at 2 small rural multi-casemix health services (Coonabarabran Health Service [CHS] and Wellington Health Service [WHS]). An integrated area-wide model of rehabilitation service delivery was developed through collaboration among the area health service (Macquarie Area Health Service [MAHS]), Lourdes Hospital and Community Services (an affiliated health organisation within MAHS and local specialty rehabilitation provider, referred to herein as Lourdes) and the author. The model was used to guide the introduction of rehabilitation for patients with less complex rehabilitation needs at CHS and WHS, under the guidance and leadership of Lourdes.

Lourdes provides specialist inpatient and outpatient services and is located near the base hospital in the regional town Dubbo, 426 km north-west of Sydney at the crossroads of the Mitchell and Newell Highways. The 30 inpatient beds consisted of 21 rehabilitation beds, 4 GEM beds and 5 palliative care beds.

Prior to the introduction of rehabilitation at CHS and WHS, rehabilitation education was provided for the nursing staff. Initially, the author conducted a two-day introduction to rehabilitation education program at each site. Following this, three rural clinical nurse consultants joined the author to facilitate the development of clinical rehabilitation skills in the workplace at CHS and WHS. At this time, several nurses from CHS and WHS also attended a one-day rehabilitation nursing workshop at Lourdes. In addition, some community consultation took place in both locations regarding the introduction of rehabilitation, but only limited information about this was available for either town.

Methods

In order to study the introduction of rehabilitation as a new service type, quantitative and qualitative methods were used. Information about bed occupancy and patient participation in rehabilitative activities were collected from hospital databases and patient observation by staff over a 10 month period. These data were analysed quantitatively using descriptive statistics. In particular, answers to the following questions about bed occupancy and patient participation rehabilitation activities were sought:

Bed occupancy:

- Did the total number of patients hospitalised for rehabilitation per annum in MAHS change following the introduction of rehabilitation at CHS and WHS?

- Did the total number of rehabilitation bed days per annum change in MAHS following the introduction of rehabilitation at CHS and WHS?

- Did the length of stay (LOS) for rehabilitation patients in MAHS change following the introduction of rehabilitation at CHS and WHS?

- Did the total number of GEM patients hospitalised per annum in MAHS change following the introduction of rehabilitation at CHS and WHS?

- Did the distribution of rehabilitation bed days per annum among the health facilities in MAHS change following the introduction of rehabilitation at CHS and WHS?

Rehabilitative activities:

- What percentage of patients at CHS, WHS and Lourdes wore day clothes?

- What percentage of patients at CHS, WHS and Lourdes ate in a dining room?

- Did patient participation in rehabilitative activities (wearing day clothes and eating in a dining room) differ among sites (CHS, WHS and Lourdes)?

Qualitative data involved semi-structured interviews with 10 hospital employees, including both clinical and non-clinical staff. This enabled exploration of the perceptions and experiences of staff working at CHS and WHS regarding the introduction of rehabilitation as a service type.

Setting

The CHS and WHS were part of MAHS, which on 1 January 2005 (as a result of a realignment of area health service boundaries) became part of the Greater Western Area Health Service (GWAHS).

The CHS is in Coonabarabran, a small rural town approximately 160 km north-east of Dubbo. As a state suburb, the population of Coonabarabran was 3421 in 20069. The CHS had 25 inpatient beds, a 24 hour emergency department and community health service. Before the introduction of rehabilitation, CHS provided general medical, minor surgical, paediatrics, haemodialysis and palliative care, as well as radiography. Clinical inpatient care was provided by GPs, registered and enrolled nurses and a physiotherapist. Some new equipment was purchased and minor building alterations were undertaken before rehabilitation commenced.

The WHS is in Wellington, a small rural town approximately 50 km south-east of Dubbo. The population of Wellington Local Government Area was 8120 in 200610. The WHS had 33 inpatient beds, a 24 hour emergency department and community health services. Before the introduction of rehabilitation, WHS provided general medical, minor surgical, paediatrics, haemodialysis and palliative care, as well as radiography. Clinical inpatient care was provided by GPs, registered and enrolled nurses and physiotherapists. Some new equipment was purchased and necessary building alterations were identified but not undertaken, before rehabilitation commenced.

Data collection

Data collection commenced following approval from three human ethics committees (two clinical and one university).

Quantitative data: Bed occupancy data relating to rehabilitation and GEM admissions were collected from 2 sources. The GWAHS data bases were accessed for data relating to rehabilitation and GEM admissions for the whole of the former MAHS. The second set of bed occupancy data was recorded daily by nursing staff at each of the 3 sites (WHS, CHS and Lourdes) on 'data collection sheets', which were specifically designed for this project, for the period 22 February-31 December 2005.

The numbers of patients observed to dress in day clothes and eat meals at a dining table were also recorded daily by nursing staff at each of the 3 sites on the data collection sheets. Data were recorded for all inpatients, not just patients classified as rehabilitation or GEM, for the period 22 February-31 December 2005. The patients were not aware they were being observed.

All data were numerical and contained no identifying information about individual patients. The GWAHS data were provided in an Excel spreadsheet and stored as password-protected files. The completed data collection sheets were stored by the nursing staff at each site and collected by the researcher during periodic visits. Following this, data were entered into an Excel spreadsheet and stored as password-protected files.

Qualitative data: Staff working at CHS and WHS were invited to participate in a series of 3 semi-structured interviews using open-ended questions by distribution of a participant information sheet and consent form. The only inclusion criterion was the ability to speak English fluently. Staff expressed interest in participating in the interviews by directly approaching the researcher and signing the consent form.

Ten staff from CHS and 10 from WHS participated in interviews, each of which lasted between 20 and 60 min. Fifteen completed all 3 interviews (Table 2). Reasons for not completing all 3 interviews were: staff resignation, staff relieving at another service for the period between interviews, and staff on leave when an interview was scheduled.

Table 2: Summary of interviews

Fifteen participants were female and five were male. Their ages ranged from 31 to 61 years with a mean age of 46.1 years. Twelve participants (6 at each site) were nursing staff who worked either a mix of rotating rosters or mainly Monday to Friday morning shifts. Others were managers, physiotherapists or non-clinical staff. Ten were employed full time and 10 part time. Time in their current position at the first interview ranged from 7 months to 30 years.

The author conducted the interviews in a private office in each participant's work place during working hours between February 2005 and January 2006. All interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim.

The interviews included questions such as:

- Please tell me about the introduction of rehabilitation at (name of health service).

- What differences have you noticed since rehabilitation services were started?

- What has the introduction of rehabilitation meant for you in your role here?

Data analysis

Quantitative data: SPSS software (SPSS; Chicago, IL, USA; www.spss.com) was used to generate descriptive statistics for bed occupancy and the number of patients dressing in day clothes and eating meals at a dining table. In addition, correlations between bed occupancy and the numbers of patients participating in the rehabilitative activities were calculated.

Qualitative data: Interview transcripts were analysed qualitatively by the author. Analysis was informed by Strauss and Corbin11 to inductively identify the common and not-so-common themes. The transcripts were analysed in sub-sets to capture similarities and differences across time and between sites. Given the potential for breach of confidentiality in such small sample sizes and communities, data from clinical and non-clinical participants were not compared. After reading and re-reading each transcript, descriptive codes were assigned to strings of text. On completion of the assigning of descriptive codes for all transcripts in a sub-set, clusters of similar codes were labelled as first-level themes. These themes were later clustered and labelled as higher-order themes. Sub-sets were also compared for similarities and differences.

The findings of the analysis of the CHS interviews were drafted into a three-chapter 22 560 word story. To ensure the credibility and confirmability12 of the Coonabarabran story, two CHS participants were asked to read and provide feedback on the draft. A similar process was undertaken regarding the 19 775 word Wellington story involving one WHS participant. All participants agreed their draft story reflected what had happened at their site. Some minor changes to terms used were recommended for each story and these were made.

Results

The key findings are that in the former MAHS between July 2002 and December 2005, the number of rehabilitation admissions increased, the number of rehabilitation bed days fluctuated, and overall rehabilitation LOS increased, but decreased at Lourdes. Only small numbers of patients at CHS and WHS were admitted under the classification of rehabilitation. The GEM classifications were only used at Lourdes, and the annual number of these admissions decreased.

Patients at all 3 sites participated in rehabilitative activities, namely dressing in day clothes and eating meals at a dining table; however, not all rehabilitation patients at CHS and WHS dressed in day clothes. Patients at CHS were more likely to eat meals at a dining table than dress in day clothes, and vice versa for those at WHS.

The uptake of rehabilitation by staff was faster at CHS than at WHS. At both sites a variety of factors enabled the introduction of rehabilitation. Perhaps the most significant of these was nurses 'growing' their role in rehabilitation. There were also numerous threats to rehabilitation at both sites. Despite these, each site developed an approach to rehabilitation that suited its particular circumstances.

Bed occupancy

There was a 64.6% increase in the number of patients admitted for rehabilitation in the former MAHS between the periods 2002-2003 (n = 226) and 2004-2005 (n = 372). The July-December 2005 data (n = 191) suggests a continuing trend.

The total number of rehabilitation bed days fluctuated between the periods 2002-2003 and 2004-2005 (Table 3).

The total number of GEM patients decreased between the periods 2002-2003 (n = 48) and 2004-2005 (n = 24). The July-December 2005 data (n = 10) suggest maintenance of similar numbers. However, because use of the GEM classification was limited to Lourdes, the available data do not accurately reflect patient types among all facilities in the former MAHS.

The number of facilities in the former MAHS (including Lourdes) that reported rehabilitation patients between the periods 2002-2003 and 2004-2005 alternated between 10 and 14. At the same time, the average LOS for rehabilitation patients for all MAHS sites steadily increased. During the same period, the average LOS for rehabilitation patients at Lourdes decreased (Table 4).

Bed occupancy by site: Details of the daily 24.00 hours count of all patients and rehabilitation patients at CHS and WHS is provided (Table 5). The number of inpatients varied throughout the data collection period, with only small numbers of rehabilitation patients on any one day. At Lourdes most patients were classified rehabilitation patients, where the major variation in patient numbers was created by closure of the service for the Christmas/New Year period.

Table 3: Rehabilitation and extended care occupied bed days (source: Greater Western Area Health Service from New South Wales Department of Health data system)

Table 4: Rehabilitation admissions and average length of stay (source: Greater Western Area Health Service from New South Wales Department of Health data system)

Table 5: Bed occupancy by site

Patients participating rehabilitative activities

Lourdes had the highest percentage of patients wearing day clothes (Table 6). This was expected, given that on average 85.6% of Lourdes patients were rehabilitation patients. At CHS and WHS, the mean number of patients wearing day clothes was less than the mean number of rehabilitation patients. This suggests that not all their rehabilitation patients dressed in day clothes.

Lourdes also had the highest percentage of patients eating meals at a dining table (Table 7). A higher proportion of CHS than WHS patients ate meals at a dining table.

At Lourdes and WHS the mean percentages of patients eating breakfast, lunch and the evening meal at a dining table were less than the mean percentage of rehabilitation patients. This suggests that not all rehabilitation patients ate meals at a dining table.

At CHS the mean percentages of patients eating lunch and the evening meal at a dining table were more than the mean percentage of rehabilitation patients, suggesting that rehabilitation and non-rehabilitation patients ate lunch and the evening meal at a dining table.

Generally speaking, patients were more likely to wear day clothes at WHS than CHS, but there was no statistical difference between the means. However, patients were more likely to eat meals at a dining table at CHS, and there was statistical difference between the means for all three meals (Table 8).

Table 6: Patients dressing in day clothes by site

Table 7: Patients eating meals at a dining table by site

Table 8: Comparison of Coonabarabran Health Service and Wellington Health Service inpatients participating in rehabilitation activities

Other differences between sites related to the statistically significant relationships among patients participating in rehabilitative activities and the number of patients and the percentage of rehabilitation patients. Higher numbers of inpatients were associated with:

- fewer patients wearing day clothes at CHS and WHS

- fewer patients eating lunch at a dining table at WHS

- fewer patients eating the evening meal at a dining table at WHS.

This suggests that the presence of higher proportions of non-rehabilitation patients impacted negatively on the likelihood that patients would participate in rehabilitative activities. Interview data from both sites support this interpretation, with participants reporting that acute patients take priority over rehabilitation patients when nurses are busy.

Higher percentages of rehabilitation patients were associated with:

- more patients wearing day clothes at WHS

- more patients eating breakfast at a dining table at CHS

- fewer patients eating breakfast at a dining table at WHS

- more patients eating lunch at a dining table at WHS.

This suggests that nurses at WHS, and to a lesser extent CHS, were more able to enact their role when the case-mix had higher proportions of rehabilitation patients and, as a consequence, lower proportions of non-rehabilitation or acute patients. At WHS, these activities occurred despite considerable difficulties encountered as a consequence of the limited space available for the dining tables, as was revealed in staff interviews.

Staff experiences and perceptions of the introduction of rehabilitation at Coonabarabran Health Service and Wellington Health Service

There were similarities in and differences between the experiences and perceptions of staff at CHS and WHS regarding the introduction of rehabilitation. In February 2005, participants at both sites reported a range of understandings and views about the introduction of rehabilitation. By mid-2005 there was agreement that rehabilitation was good for CHS, a view that was not evident at WHS until the third interviews in the period December 2005-January 2006.

At CHS and WHS various enabling activities took place, but at the same time a number of factors threatened rehabilitation at each site. These enablers and threats emerged as themes in the various temporal sub-sets of data for each site, and a summary of these is provided (Tables 9 & 10).

In essence, CHS and WHS developed similar but different approaches to rehabilitation. Indicators of each are summarised (Table 11).

Table 9: Summary of enablers and threats to rehabilitation at Coonabarabran Health Service

Table 10: Summary of enablers and threats to rehabilitation at Wellington Health Service

Table 11: Indicators of alternative approaches

The following comments from two study participants provide insight into the perceptions of CHS and WHS staff:

[The introduction of rehabilitation]...is not as big a deal as I thought it was going to be. (CHS nurse participant)

I mean we still do the same stuff that we always did, but to me [the introduction of rehabilitation has] highlighted that we're all there for the patient and we all have to work together to get that patient the best outcome. ...Everyone working together to get that happening. (WHS nurse participant)

Discussion

As the first formal study of the introduction of rehabilitation in small rural multi-casemix hospitals in Australia, this study contributes to understanding not only the introduction of rehabilitation, but also to understanding the process of change in small rural inpatient settings. This was made possible through the collection of quantitative and qualitative data and, in particular, the conduct of qualitative interviews at 3 points in time at both sites. Furthermore, studying the introduction of rehabilitation at both sites enhances transferability of findings.

Within a context of growing appreciation of the contribution that rehabilitation services can make to the quality of life of people with a range of conditions and an increasing demand for rehabilitation beds, the decision to introduce rehabilitation as a new service type in 2 small rural multi-casemix hospitals is contemporary. Instead of being hospitalised far from home, residents of the 2 rural communities participated in formal rehabilitation programs with the support of their families and friends nearby. With increasing awareness of the importance of the psycho-social domains of rehabilitation13, and a maturing understanding of the important contribution made to rehabilitation by family and friends3, rehabilitating close to home is considered desirable.

Of particular interest is the nature of the rehabilitation services provided at the 2 small hospitals. The medical care of inpatients at both sites was managed by GPs who had access to a rehabilitation physician at the specialist rehabilitation provider. Some may question whether such a service is specialist rehabilitation when, according to the Australasian Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine14,p.1, a specialist medical rehabilitation service is 'directed by a rehabilitation physician and each patient's clinical management is under the supervision of a rehabilitation physician'. Furthermore, allied health staff coverage was commonly part time and at one site physiotherapy was often the only allied health discipline available. As a consequence, nursing was the discipline primarily responsible for guiding patient rehabilitation; this is contra to an international body of literature that portrays specialist rehabilitation as reliant on extensive allied health input15,16.

However, with processes in place to ensure patients with complex rehabilitation needs were transferred to the regional specialty rehabilitation provider, staff in the smaller facilities were only expected to support the rehabilitation of patients within the scope of their rehabilitation expertise. While, generally speaking, allied health staff are familiar with rehabilitation, nurses are less so16,17. As a consequence, rehabilitation nursing expertise developed slowly at both sites. It started with the introduction of practices to normalise the patient's day, namely patients dressing in day clothes and eating meals in a dining room or at a dining table. It progressed to nurses encouraging patients to be more active and self-caring, and for some nurses teaching patients specific ways to be more independent.

Most importantly, the development of an appreciation of rehabilitation as an approach different to that used with acute care patients enabled nurses to see that other (non-rehabilitation) patients can benefit from nurses using this approach. This approach could be especially relevant for patients who have frequent hospital admissions due to chronic conditions. Nursing adopting a rehabilitative approach fits with recent initiatives to support people with chronic conditions, such as the NSW Chronic Care Program18-20 and the Australian Government Transition Care Program21 for older people. However, as suggested in this study, the actual mix of acute and rehabilitation patients may be an important consideration.

It must be stressed, however, that staff working in the small facilities relied heavily on allied health input into patient rehabilitation. While nurses acquired some rehabilitation skills, their knowledge base did not negate the need for the specialist input of physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech pathology for their formal rehabilitation patients. Furthermore, as nursing's understanding of what these disciplines had to offer grew, allied health staff were asked for their input into the care of more patients. At one site, a tendency for nurses to view allied health as being responsible for rehabilitation led to an over-reliance on allied health services. It was very clear that the full extent of nursing's rehabilitative potential at both sites is yet to be realised. This will only be possible when appropriate support is provided at a structural level.

In addition to reporting on the introduction of rehabilitation in the 2 facilities, the findings of this study also provide insight into the process of change in small rural inpatient settings. While rehabilitation was an addition to the usual business of these hospitals and was seen by some staff as 'extra work', it required staff to change the way they practised. In particular, it required nursing staff to interact with patients differently. Rehabilitation also provided a springboard for reviewing other practices, in particular communication between clinical disciplines, as well as communication between clinical and non-clinical staff. As such, the introduction of a new service type, namely rehabilitation, was advantageous as a catalyst for other changes.

In addition to variations in the readiness of staff to engage in change, the broader community was also reluctant to support the introduction of rehabilitation. This was particularly evident when patients were asked to dress in day clothes. Many patients were reluctant to discard their traditional hospital attire, and families usually needed much persuasion to provide day clothes for them. This highlights the need for community consultation as a central component of any proposal to change inpatient service delivery. Through genuine engagement with their communities, small rural multi-casemix hospitals may find the champions required to bring the community along as supporters of service developments.

Despite some staff and patient reluctance, change did take place. Associated with the introduction of rehabilitation as a new service type, a new model of inpatient service delivery emerged at each site. In addition, local staff at both sites initiated additional changes that enhanced inpatient care in general. However, the extent to which these initiatives are sustainable is not clear. Local leadership is critical for the success of new service types, especially when these are in addition to the existing casemix, as was the case in this study. At the same time, leadership from specialty rehabilitation providers is critical to the ongoing development of an integrated network of rehabilitation providers to ensure that the role of all network members is clear and the staff at each site are adequately prepared to meet the rehabilitation needs of their patients.

It is apparent from this study that rehabilitation services can be provided at several levels. In addition to specialist rehabilitation services, individuals and communities could benefit from nurse-initiated rehabilitation-focused inpatient care. Furthermore, as rural communities across Australia age and the Australian population as a whole is experiencing more chronic conditions and disability, this could become an important focus for small rural multi-casemix hospitals.

This study has some limitations. The first is that the study was time-limited and has therefore only captured the beginning of change in the 2 facilities. As a result, the extent to which any or all of the changes have been sustained over time is unknown. The second is that reliance on clinical staff to collect numerical data on a daily basis meant that data sets were not always complete and, given the nature of some of the data, secondary sources were not always available to assist in finding missing data. Third and most importantly, patients' experiences and perceptions of rehabilitation in their local multi-casemix rural hospitals were not gathered, nor were patient outcome data collected. It is not known if patients were satisfied with the processes and outcomes of these rehabilitation services.

Conclusion

It is apparent from this study that rehabilitation services can be provided at several levels throughout rural Australia. When linked to a specialty rehabilitation provider, small multi-casemix rural hospitals appear to have the potential to support the rehabilitation of patients with uncomplicated rehabilitation needs in their local communities. This may either be through the early transfer of patients from specialty rehabilitation beds to continue their rehabilitation closer to home, or through new programs aimed at enhancing the self-care efficacy of people with chronic conditions.

To fully realise this potential, and because small rural hospitals are primarily staff by nurses, nursing staff working in these facilities need to be supported to develop their rehabilitative potential. This support should come from the collective wisdom of specialist rehabilitation nurses, medical rehabilitation specialists and allied health staff, and must be provided at the broader structural level. Through cross-disciplinary sharing of knowledge and skills, residents of rural communities could spend less time hospitalised at long distances from their homes.

Acknowledgments

The Greater Western Area Health Service, Catholic Health Care Service and Royal Rehabilitation Centre Sydney funded this project. The support of the staff from the former MAHS and GWAHS (in particular Coonabarabran and Wellington Health Services) and Lourdes is also acknowledged, without their support the project would not have been possible. The contribution of John Bidewell, who conducted the statistical analysis, was also invaluable.

References

1. Wade D. Describing rehabilitation interventions. Clinical Rehabilitation 2005; 19: 811-818.

2. Pryor J. Nursing and rehabilitation. In: J Pryor (Ed.). Rehabilitation - a vital nursing function. Canberra, ACT: Royal College of Nursing Australia, 1999; 1-13.

3. Ellis-Hill C, Payne S, Ward C. Using stroke to explore the Life Thread Model: an alternative approach to understanding rehabilitation following an acquired disability. Disability & Rehabilitation 2007; 30(2): 150-159.

4. Smith DS. A history of rehabilitation in Australia. Fellowship Affairs 1994; 13: 38-40.

5. Simmonds F, Stevermuer T. The AROC annual report: the state of rehabilitation in Australia 2005. Australian Health Review 2007; 31: S31-S53.

6. Pryor J. A grounded theory of nursing's contribution to inpatient rehabilitation.

7. New South Wales Department of Health. A policy framework for medical rehabilitation in NSW. Sydney, NSW: NSW Health Department, 1995.

8. New South Wales Department of Health. NSW SNAP Data Collection Data Dictionary Version 2. Sydney, NSW: NSW Health Department, 2002.

9. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2006 Census of Population and Housing. (Online) 2008. Available:

http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/ABSNavigation/prenav/LocationSearch?locationLastSearchTerm=Coonabarabran&locationSearchTerm=

Coonabarabran&newarea=SSC16809&submitbutton=View+Community+Profiles+%3E&mapdisplay=on&collection=Census&period=2006&areacode=SSC16809&

geography=&method=&productlabel=&producttype=Community+Profiles&topic=&navmapdisplayed=true&javascript=true&breadcrumb=

PL&topholder=0&leftholder=0€taction=104&action=401&textversion=false&subaction=1 (Accessed 6 May 2008).

10. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2006 Census of Population and Housing 2008b. (Online) 2008. Available:

http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/ABSNavigation/prenav/LocationSearch?locationLastSearchTerm=wellington&locationSearchTerm=wellington&newarea=LGA18150&submitbutton=View+Community+Profiles+% 3E&mapdisplay=on&collection=Census&period=2006&areacode=LGA18150&geography=&method=&productlabel=&producttype=Community+Profiles &topic=&navmapdisplayed=true&javascript=true&breadcrumb=PL&topholder=0&leftholder=0€taction=104&action=401&textversion=false&subaction=1 (Accessed 2 April 2008).

11. Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedure for developing grounded theory, 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1998.

12. Guba EG. Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiry. Educational Communication and Technology Journal 1981; 29(2): 75-91.

13. Nolan M, Booth A, Nolan J. New directions in rehabilitation: exploring the nursing contribution. London: The English Board for Nursing, Midwifery and Health, 1997.

14. Australasian Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine. Rehabilitation Service Categories. Sydney, NSW: Australasian Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine, 2006.

15. Manley S. The rehabilitation team. In: M Grabois, SJ Garrison, KA Hart, LD Lehmkuhl (Eds). Physical medicine and rehabilitation: the complete approach. Boston, MA: Blackwell Science, 2000; 26-32.

16. Norrefalk J. How do we define multidisciplinary rehabilitation? Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine 2003; 35: 100-101. (Letter)

17. Pryor J. How prepared are nurses for practice in a rehabilitation setting? Royal Rehabilitation Centre Sydney, monograph series no 1. Sydney, NSW: Royal Rehabilitation Centre Sydney, 1999.

18. New South Wales Department of Health. NSW Chronic Care Program: Phase Two 2003-2006. Sydney, NSW: New South Wales Department of Health, 2004.

19. New South Wales Department of Health. NSW Chronic Care Program: Rehabilitation for Chronic Disease volume 1. Sydney, NSW: New South Wales Department of Health, 2006.

20. New South Wales Department of Health. NSW Chronic Care Program: Implementing Rehabilitation for Chronic Disease volume 2. North Sydney: New South Wales Department of Health, 2006.

21. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Transition Care Program, program guidelines. (Online) 2005. Available: http://www.healthconnect.gov.au/internet/wcms/publishing.nsf/content/ageing-policy-transition.htm (Accessed 1 May 2008).