Context

WHO and the International Diabetes Federation have predicted that the number of adult-onset diabetics worldwide would more than double by 2030 from the present level of 171 million to 366 million1. This increase would be approximately 42% in developed countries and approximately 150% in developing countries. The maximum increase is in expected in India. In India, diabetic retinopathy was the 17th cause of blindness 20 years ago; today it has ascended to the 6th position. A third of the people with diabetes are unaware that they have the disease. A person with diabetes is 25 times more likely to go blind than a person in the general population. The annual cost of treating a person with diabetes at risk is much lower than the welfare benefits paid to a blind person per annum, particularly in some developed countries2.

Issue

'Right to Sight' is a global initiative (Vision 2020) designed to eliminate avoidable blindness by 2020. This concept was built on the foundation of community participation, along with an emphasis on the development of human resources infrastructure and technology for eye care, plus cost-effective disease control interventions. Currently diabetic retinopathy is considered one of the priority areas in the Vision 2020 program.

Sankara Nethralaya, a non-profit, non-commercial ophthalmic organization was founded in 1978, in Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. Today, it is a renowned Indian tertiary eye institute with a track record of undertaking community services since its inception. Recognizing its social responsibility, Sankara Nethralaya has embarked on a major outreach program on diabetic retinopathy with financial support from the Lions Clubs International Foundation and the RD Tata Trust, Mumbai, India.

Preparatory phase

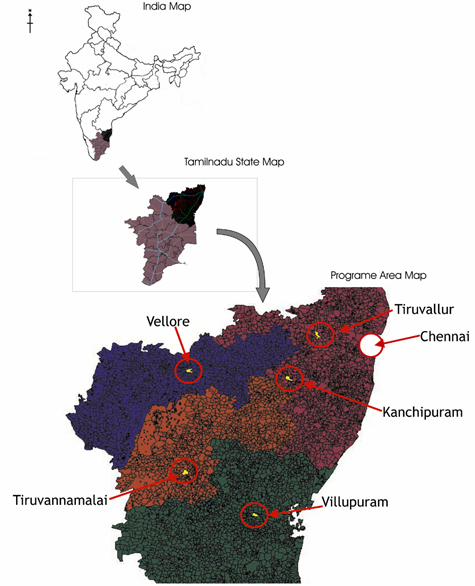

Target areas: This program envisages covering six rural districts and urban slums of Chennai city, Tamil Nadu state of South India, over a period of 3 years (Fig 1).

Figure 1: Map of the project area.

Team: The project team includes four retinal specialists, one genetic researcher, one epidemiologist, two optometrists, two research fellows, one fundus photographer, and 10 social workers. A detailed manual covering all the important activities of the field operation was prepared.

Survey: Prior to screening, a survey was conducted by social workers in the selected villages to discover available resources and possible locations for screening camps. In order to increase the referral of persons with diabetes to the screening camps, social workers met local diabetologists and GPs. A database of addresses was also created for continuing medical education program. This type of survey assisted in assessing the extent of existing eye care facilities with respect to diabetic retinopathy.

Pilot study including time-motion to ensure quality control: All of the team members underwent intensive training for one week, 8 hours a day. All team members were given orientation to the anatomy and physiology of the eye, and also to diabetes and diabetic retinopathy. Training was given for accurate measurement of blood pressure (BP) and estimation of capillary blood glucose. Each trainee was evaluated before he or she was allowed to participate in the study. Expert diabetic educators and dieticians held counseling sessions. A pilot study involving 100 volunteers was conducted; time-motion study was conducted to estimate the time needed for each task. The aim was to avoid biases or errors in any of the procedures employed and to ensure that each member of the team was well trained in the screening procedures, including filling out the study data sheet. In order to ensure quality control, the BP apparatus and glucometer were validated and calibrated at regular intervals. Random monitoring of the team members was conducted as they counselled patients.

Sankara Nethralaya diabetic retinopathy model

This program aimed to achieve the following objectives:

- To create awareness about diabetes and diabetic retinopathy in the general population in Indian rural areas.

- To conduct diabetic screening camps for early detection and prompt treatment of sight threatening diabetic retinopathy.

- To train general ophthalmologists and general physicians in diagnostic techniques to identify patients at risk of developing diabetic retinopathy.

- To perform relevant biochemical and genetic investigations to discover the risk factors associated with the development of diabetic retinopathy

Awareness strategy: Approximately 12.5 million people live in the study areas. A targeted awareness strategy was implemented using several methods.

Meetings Awareness meetings were held in the target areas at least a month prior to the screening camps. The target was to organize approximately eight to nine such meetings in each district over a period of 5-6 months. The target group for awareness meetings included persons with diabetes, high-risk general population, Lions Club members, young persons and pensioners, women's self-help groups, para-medical staff, pharmacists and industrial workers.

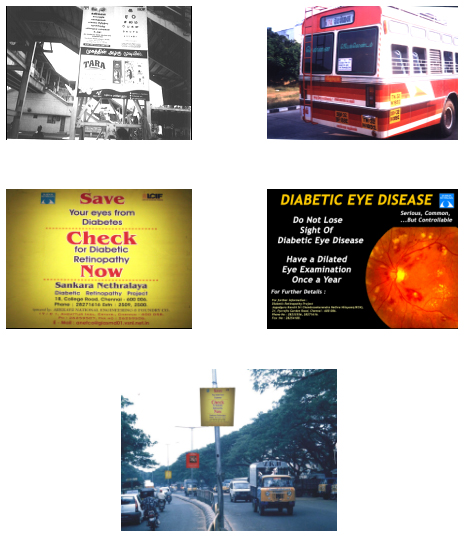

Visual aids These were pamphlets, leaflets, banners, lamp pole kiosks (a cylindrical structure on which awareness message containing card boards were displayed), wall paintings, stickers on city buses, posters, and audiovisual CDs containing information on diabetes and diabetic retinopathy. Leaflets were distributed approximately one week before starting a screening camp. Lamp pole kiosks were displayed at prominent locations. Pamphlets were distributed to people attending awareness meetings and screening camps. Two audiovisual CDs were prepared; one was an educational CD on diabetic retinopathy, and the other in traditional Tamil folk art medium, called Villupattu, being an effective awareness medium among the rural population (Fig 2).

Figure 2: Various awareness aids used in the campaign.

Media All types of media were used to propagate and disseminate information; these included newspaper articles, press releases, radio talks, cable TV advertisements, SMS and internet messages, and digital display in post offices and railway stations.

Celebrations Special events were organized on special days such as the World Sight Day (October 14), and the World Diabetic Day (November 14) during the project period.

Outcome measure of awareness campaign: A KAP (knowledge, attitude, practice) study was conducted before and after each awareness meeting. Separate KAP questionnaires were prepared for the general population, general physicians, and general ophthalmologists.

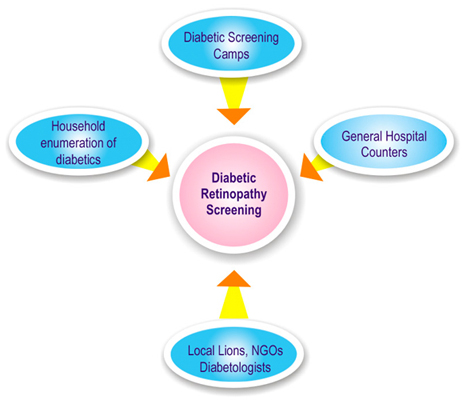

Screening strategy: It was envisaged that approximately 250 persons with diabetes would be screened in one day; therefore, various recruitment approaches were adopted to attain maximum yield (Fig 3).

Figure 3: Various recruitment strategies.

At the diabetic screening camps (Fig 4a), the finger-prick method for random blood sugar estimation (glucose oxidase method) was performed using a glucometer (Accutrend Alfa; Boehringer Mannheim, Germany). General population above the age of 30 years underwent initial diabetic screening. Newly diagnosed (provisional) diabetes was defined as the one whose random blood glucose was more than 200 mg/dL (11.1mmol/L)3; these patients did not undergo further tests such as oral glucose tolerance test. All persons with diabetes (known, provisional or borderline - random blood sugars between 144 and 149 mg/dL or 7.8-11 mmol/L) were counselled and referred to the diabetologists for further evaluation and management.

Figure 4a: Flow chart illustrating diabetes screening strategy.

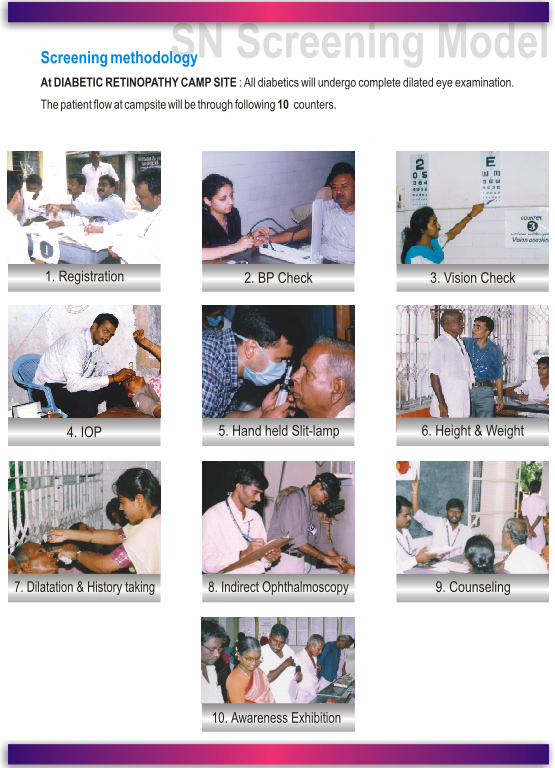

At the diabetic retinopathy screening camps, all persons with newly diagnosed (provisional) diabetes, plus persons with known diabetes (referred from general physicians and diabetologists) were screened. The flow of diabetic retinopathy screening is illustrated (Fig 4b). In diabetic retinopathy screening camps a detailed history was obtained containing study variables such as duration of diabetes, type of treatment, physical activity status, alcohol intake, smoking status, family history of diabetes4 and family income5. Ocular history included details of first and last eye examination, nature of present eye complaint, any laser or ocular surgery. Anthropometric measurements such as height and weight for calculating body mass index (BMI) were measured for all persons with diabetes attending diabetic retinopathy screening camps6. Community halls or schools were selected for conducting screening camps through 10 centres (Fig 5).

Figure 4b: Flow chart illustrating diabetes retinopathy screening strategy.

Figure 5: Patient flow at the Diabetic retinopathy camp site.

Visual acuity was measured using LogMAR chart. A hand-held (Heine HSL 100 CE; HEINE Technical, Germany) slit-lamp was used for anterior segment evaluation including the depth of anterior chamber and rubeosis iridis. Intraocular pressure measurement was performed with Schiotz indentation tonometer (Schiotz, John Weiss & Son Ltd, London, UK). Dilated fundus evaluation was done with binocular indirect ophthalmoscope (Keeler Instrument Inc., PA, USA) and +20D Nikon lens. Diabetic retinopathy was graded as per the new disease severity scale given by the American Academy of Ophthalmology7. Patients with narrow angles and sight threatening diabetic retinopathy were re-examined at the base hospital in order to undergo fluorescein angiogram or ultrasound and treatment such as laser photocoagulation or vitreous surgery.

Educational strategy: Continuing medical education (CME) programs were organized for GPs for updating themselves in diabetes and diabetic retinopathy. The focus was to encourage fundus evaluation for all diabetics for early recognition of diabetic retinopathy.

Investigational strategy: Patients with sight threatening diabetic retinopathy underwent biochemical and genetic analysis. Biochemical studies included estimation of total serum cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein, serum triglycerides, and hemoglobin, packed cell volume and glycosylated hemoglobin fraction, and microalbuminuria. Genetic study included screening for polymorphisms and sequence variants (VEGF, PKC-β, receptor for AGEP and ApoE) and their association with the diseases in the candidate genes. The investigations on patients were performed in accordance with the 'Declaration of Helsinki'8.

Program achievements

Since the launch of the program in June 2003, we have successfully covered three rural districts. Altogether, 103 awareness meetings covering approximately 100 000 population were held. Stickers containing diabetic retinopathy awareness messages were displayed at railway stations, public transport systems and post offices targeting approximately 2.5-3 million people.

To date, of the 25 313 general population who underwent diabetic screening, the prevalence of diabetes mellitus was found to be 21.7%; however, the point prevalence of newly detected diabetes mellitus was 4.5%. Of the 7770 diabetic patients who underwent diabetic retinopathy screening, the prevalence of any retinopathy was 17.6%; of these 17.6%, sight-threatening retinopathy was evident in 5.9%. Two CMEs on diabetes and diabetic retinopathy were organized, training 23 ophthalmologists and 43 general physicians.

The interim analysis of KAP (knowledge, attitude and practice) data revealed significant improvement in the awareness on several important parameters. These parameters included awareness of diabetes mellitus (before, 76%; after, 98%), awareness of diabetic retinopathy (before, 29%; after, 96%), need for regular eye examinations (before, 57%; after, 98%), and role of laser in preventing visual loss (before, 17%; after, 81%).

Current issues

As the program has been implemented effectively, community response has been very encouraging. On one day, almost 1000 individuals came for diabetic retinopathy screening, against the target of 250. However, in order to ensure quality care, we did not screen beyond 300 persons with diabetes on that day. The others were counseled and registered for the next camp.

Because diabetes and diabetic retinopathy is a chronic disease, the cost of health care calls for constant funding in order to provide free treatment. Due to the high volume patient load, costly equipment like laser machine cable does undergo wear and tear and requires frequent replacement.

Keeping the team focused on the objectives of program is an important and challenging task.

The future

- Telescreening for diabetic retinopathy as a pilot study is being attempted. This would facilitate examining a large section of the rural community, particularly in those areas where healthcare access is limited.

- Awareness campaigns need to be sustained with a slogan: all people with diabetes need dilated eye examination once a year.

- The training of general physicians and para-medical personnel about referral guidelines on eye examinations is important in the development of an integrated diabetes healthcare network.

- Community participation is the key to success for any awareness or screening model. Local village groups like women's self-help groups play an important role in motivating diabetics to attend screening camps.

- The role of social worker was vital in the diabetic retinopathy-screening model for effective implementation; he or she served as a link between the community and diabetes healthcare professionals.

- Community halls and schools are the best locations for conducting camps. These locations facilitate the smooth flow of patients at the campsite.

- Support from voluntary organizations like local Lions Clubs has been outstanding.

- An inbuilt recall system will monitor follow up of treated patients, as well as those patients who drop out of the program.

- Residents develop interest in community programs by participating in the outreach screening camps.

- Training local ophthalmologists and GPs in rural areas helps in the continuity of diabetic care.

- Weekly review meetings among the team members and visits by funding cum monitoring teams assists in keeping the targets in focus.

The effectiveness of this program should inspire others to follow similar diabetes screening models in the overall care of rural people with diabetes, who are underprivileged compared with the urban population.

The present screening model is somewhat different from other reports9,10. Differences include an extensive awareness program, besides screening for diabetes and diabetic retinopathy. Another difference is the use of indirect ophthalmoscopy as a screening tool, in contrast to seven-fields photography methods which are not only expensive, but also may not be feasible to adopt in rural areas. In addition, our model incorporates the training of general physicians and ophthalmologists from the study areas, in order to sustain the objectives of this study.

Developing a dedicated and integrated diabetes care team is mandatory for the prevention of blindness caused by diabetic retinopathy.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to the Lions Clubs International Foundation and RD Tata Trust, Mumbai, for the generous grant provided for the project.

References

1. Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 1047-1053.

2. James M, Turner DA, Broadbent DM, Vora J, Harding SP. Cost effectiveness analysis of screening for sight threatening diabetic eye disease. BMJ 2000; 321(7258): 424.

3. Lamb EJ, Day AP. New diagnostic criteria for diabetes mellitus: are we any further forward? Annals of Clinical Biochemistry 2000; 37: 588-592.

4. United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes study Group. 30 Diabetic retinopathy at diagnosis of non-insulin-dependant diabetes mellitus and associated risk factors. Archives of Ophthalmology 1998; 116: 297-303.

5. Dandona L, Dandona R, Naduvilath TJ, McCarty CA, Rao GN. Population based assessment of diabetic retinopathy in an urban population in southern India. British Journal of Ophthalmology 1999; 83: 937-940.

6. Narendra V, John RK, Raghuram A, Ravindran RD, Nirmalan PK, Thulasiraj RD. Diabetic retinopathy among self-reported diabetics in southern India: a population based assessment. British Journal of Ophthalmology 2002; 86: 1014- 1020.

7. Wilkinson CP, Ferris FL, Klein RE et al. Proposed international clinical diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema disease severity scales. Ophthalmology 2003; 110: 1677-1682.

8. Touitou Y, Portaluppi F, Smolensky MH et al. Ethical principles and standards for the conduct of human and animal biological rhythm research. Chronobiology International 2004; 21: 161-170.

9. Mak DB, Plant AJ, McAllister I. Screening for diabetic retinopathy in remote Australia: a program description and evaluation of a evolved model. Australian Journal of Rural Health 2003; 11: 224-30.

10. Reda E, Dunn P, Straker D et al. Screening for diabetic retinopathy using the mobile retinal camera: the Waikato experience. New Zealand Medical Journal 2003; 116(1180): U562.