Introduction

In 1996, the Australian Government established the first regionally based, multi-professional university department of rural health (UDRH).1,2 The UDRH program aimed to provide education and training facilities in non-metropolitan centres across Australia, thereby helping to attract health professionals to practise in rural and remote communities. The program continues as one of several government initiatives in tertiary education designed to strengthen and sustain rural and remote health care. These include admitting more students of rural origin into health courses and requiring at least 1 year of clinical training in a rural or remote community for 25% of Australian medical students (Rural Clinical Training and Support Program – Rural Clinical Schools).3 The rationale of these initiatives was an expectation that local access to clinical training for students of rural and remote origin and extended clinical exposure of other students interested in rural health care would increase the likelihood of employment uptake in these areas post-graduation.

Currently, there are 12 UDRHs located across Australia (one UDRH reformed into two independent campuses since 2013), all having the shared purpose of leading the rural and remote health agenda in education and research.4 UDRHs operate as clinical academic units located within the health service sector and have proximity to student placements. They serve a defined region and have sufficient critical mass to develop and deliver academically enriched clinical education and training, and the capacity to manage and coordinate placements and undertake targeted research relevant to the region.5-7 UDRHs can be major participants in health workforce education and development for students, early-career health professionals and established practitioners, and a key partner in the planning and development of the health workforce to assist in the development and delivery of health services relevant to their region. UDRHs are administered predominantly by metropolitan-based medical schools or faculties of health science and collaborate with other rurally based education providers (ie schools of rural health, other university departments of rural health) and multiple Australian universities. Internationally, the authors are aware of only one other similar large-scale multidisciplinary national program, the Area Health Education Center Program in the USA, which was established by the US Federal Government in 1972 and focused on health workforce in underserved rural and urban populations.8

The last formal evaluation of the UDRH program, which was conducted in 20089, reported that, ‘Nationally, the UDRHs have made significant contributions to rural clinical training, rural health service innovation and population health research, and increased rural community engagement with health promotion and population health awareness’ (p. 59). However that report did not include a detailed, empirical analysis of the geographic reach, activities, and outputs of UDRHs.

The funding of the UDRHs has recently been doubled to support increased training activity and expand their regional footprint. The Australian Government has also recently announced funding to establish three additional UDRHs: in the Broome and Kimberley region in Western Australia, the southern and central region of New South Wales, and the south-eastern region of Queensland. This article assesses the performance of the UDRH Network prior to the expansion funding announced in late 2015 in the following areas: geographical coverage across rural and remote Australia, student activity, contributions to rural workforce and health service development, engagement with rural communities, and research outputs.

Methods

Mixed methods were employed. Descriptive statistical methods were used to determine geographical coverage of UDRHs across Australia, and the pattern and trends of student education and training activity. Data were obtained from annual UDRH key performance indicator (KPI) reports to the Australian Government Department of Health detailing undergraduate- and graduate-entry domestic student clinical placement activity (of duration ≥2 weeks) between 2009 and 2013, and research publications for 2013. For each UDRH, additional administrative data reporting where students were placed in 2013 were mapped to local government areas in order to derive a primary geographical footprint for each UDRH.10 Areas with a population density of <1 person per km2 were designated as ‘remote’. Student access to each UDRH footprint was calculated as a ratio of the number of students on placement in 2013 to resident population. Further confirmation of regional engagement was provided by self-reports of the location of UDRH infrastructure (accommodation and educational facilities), funded positions, and formal and informal agreements with, and support for, health services, clinicians, and communities.

Discipline-specific access to clinical training within the UDRH Network was determined by comparing student placement numbers in 2013 with an estimate of the number of Australian domestic enrolments annually in tertiary health programs across Australia. Equivalent full-time student load (EFTSL) data from 201311 were used to estimate the number of students enrolled each year, dividing the EFTSL by the course duration, because published data on commencements were only available for medicine, nursing, and dentistry.12 Commencement data in these disciplines provided independent verification that the indirect method gave acceptable estimates (eg the nursing total of 41 286 EFTSL in 2013 for a course duration of 3 years yielded an estimated average of 13 762 students enrolled each year, compared with actual enrolments of 13 829 in 2010 and 13 749 in 2011).

The abstracts of all peer-reviewed research outputs generated by UDRHs and listed in KPI research activity reports for 2013 were reviewed and classified according to the broad type of research (workforce, clinical/health services, population health), topic areas (mental health, diabetes), and rural/remote focus.

Interviews were conducted with key staff across the UDRH Network about their clinical placement programs and work with rural and remote communities. Content analysis was used to identify clinical training programs, additional educational opportunities delivered by the UDRHs, and collaborative projects that demonstrated engagement in their region. Questions about clinical placements included the source of students (feeder universities), infrastructure (such as accommodation), placement coordination, student support, program delivery, educational activities, and staff support and development. In addition, the authors examined up to three sentinel projects from each UDRH in order to explore how the UDRHs engaged with health services, practitioners, non-health agencies, and communities in their respective regions. For each project information was collected about what the UDRH aimed to achieve, who was involved, who initiated it, and the UDRH contribution. Because the projects were at different stages of development, a formal assessment of project outcomes was beyond the scope of the review.

Ethics approval

The University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee approved the study (project no. 2014/636). All 11 UDRHs agreed to participate.

Results

Geography and student placements

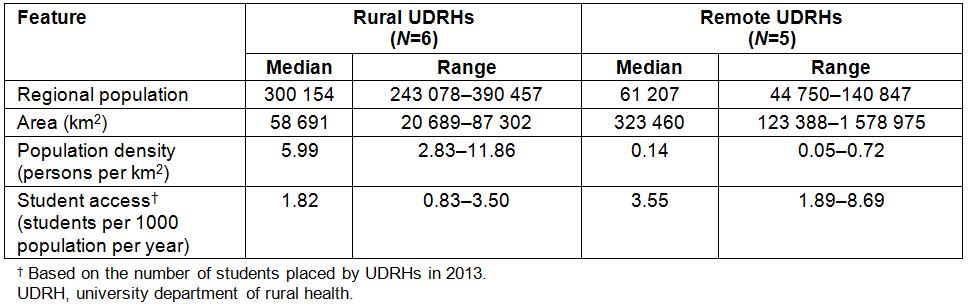

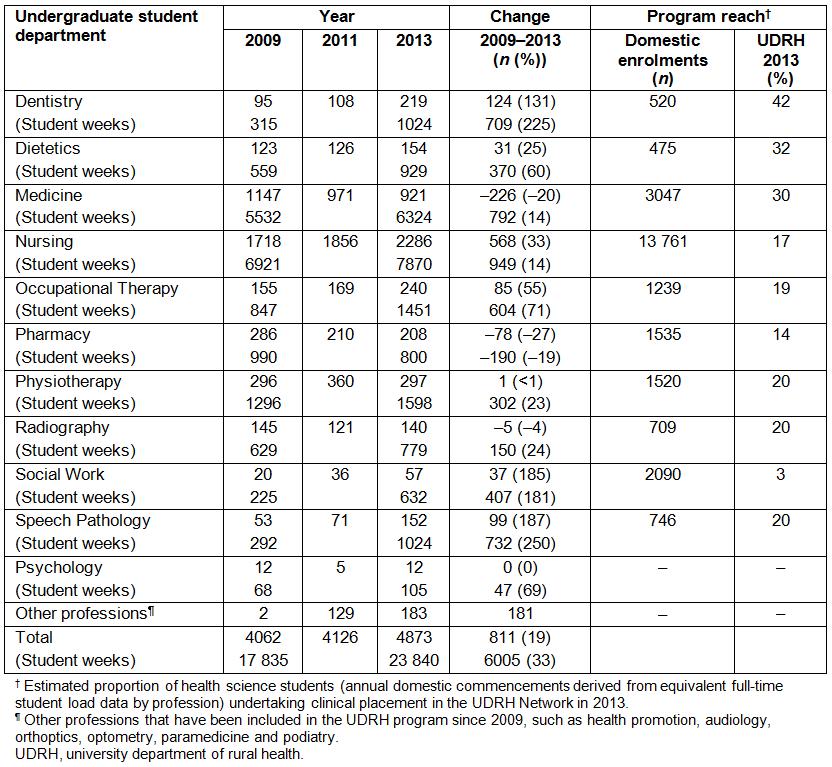

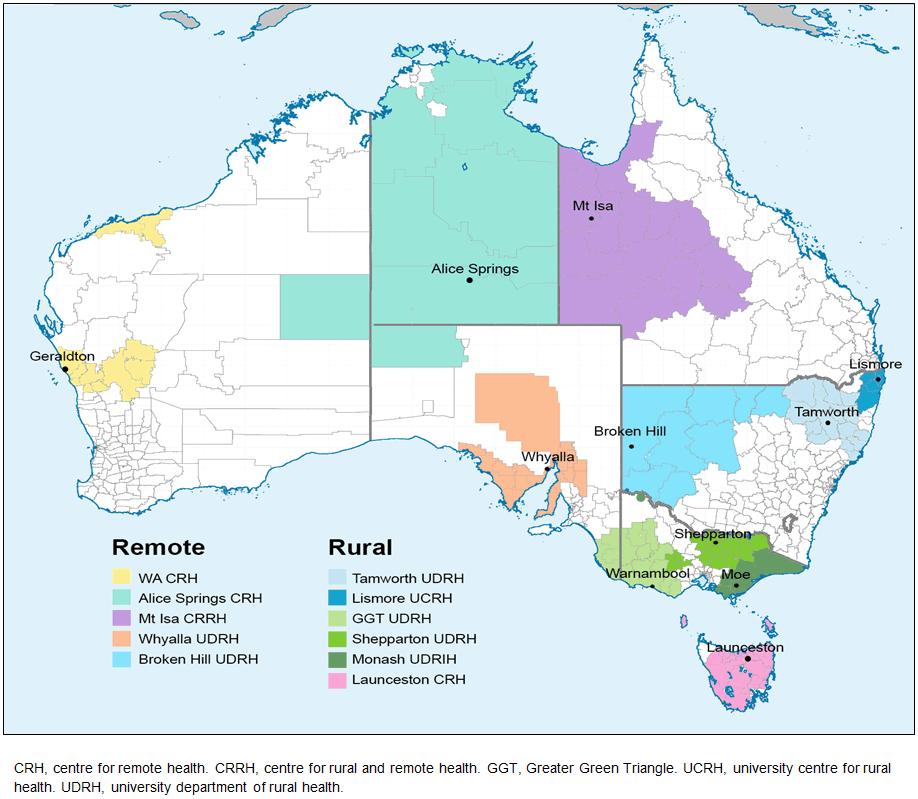

In 2013, The UDRH Network (Fig1) covered an area of 3.152 million km2 – 40.9% of Australia’s landmass – with a resident population of 2 207 426 (constituting 10.3% of the total Australian population and 34.2% of Australia’s rural population). Six UDRHs were located in ‘rural’ regions and five in ‘remote’ regions. While on average the rural regions were one-sixth of the size and had populations five times larger than remote regions, student ‘access’ to UDRH-supported clinical training was greater in remote regions, with a median of 3.55 students per 1000 population, than in rural regions, where the figure was 1.82 (Table 1). From 2009 to 2013, the number of students on clinical placements within the UDRH Network increased by 19%, and the number of placement weeks grew by 33% (Table 2), resulting in an increase in average placement duration from 4.39 to 4.89 weeks. The numbers of student weeks increased in all disciplines except for Pharmacy, in which the student weeks decreased by 19%. In 2013, the estimated discipline-specific access to UDRH programs ranged from 42% of annual enrolments in Dentistry to 3% of Social Work students, with an average of 18% across the 10 leading professions accessing UDRH-supported clinical placements that year. There were only a maximum of 12 Psychology students placed annually across the network during the review period.

Table 1: Key geographical features of the rural and remotely located university departments of rural health across Australia, 2013

Table 2: Program reach: Number of students on clinical placement within the University Departments of Rural Health Network, 2009–2013, by profession

Figure 1: Region map of university departments of rural health across Australia, 2013.

Figure 1: Region map of university departments of rural health across Australia, 2013.

Clinical placement programs

Each UDRH provided data on its clinical placement program. Features common to all programs included availability of cross-cultural, interprofessional and simulation training, orientation of students to placements, and UDRH-managed accommodation. Other features varied by context across the network. For example, one remote UDRH was authorised by local health services to manage all student placements in the region, while others had established coordination hubs in several centres across their respective regions, working closely with the local health service facilities. All UDRHs supported students from multiple universities. For some, students were drawn primarily from one university (host institution) while others had agreements with, and sourced students from, many universities across Australia. Recent developments within the UDRH Network have led to increases in placement capacity and duration, and have provided opportunities for students to contribute to service delivery in underserved rural and remote communities, including through the introduction of ‘service-learning programs’ by five UDRHs since 2009. In this educational approach, students deliver clinical care under supervision in student-led clinics or in an assisting role.13

Research outputs

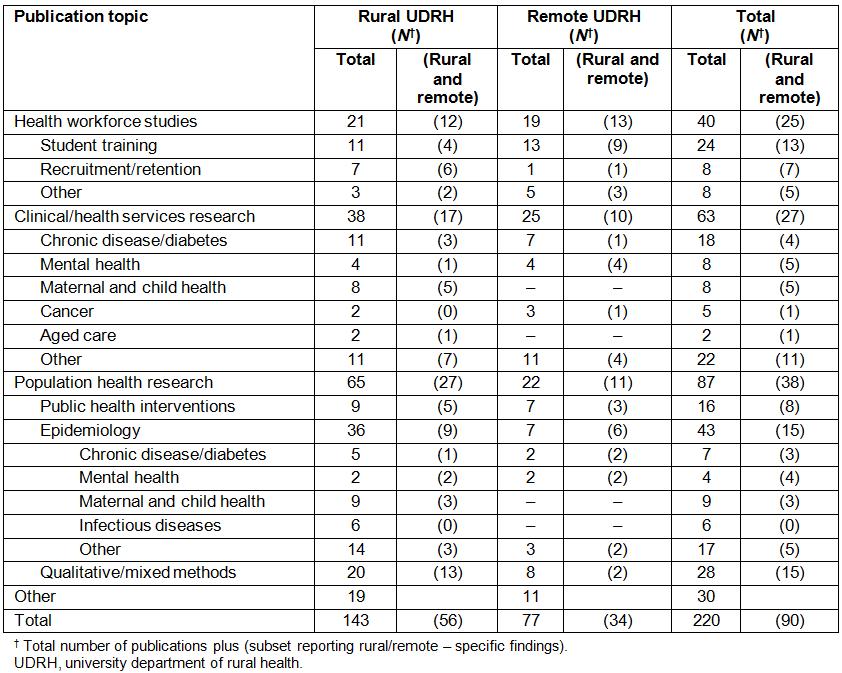

The UDRH Network published 220 co-authored peer-reviewed articles in 2013 (Table 3). Publications reported on health workforce studies (40 articles; 18%), clinical and health services research (63 articles; 29%), population health research (87 articles; 40%), and other topics including study protocols, international health studies and laboratory studies (30 articles; 14%). Forty percent of these publications (90 articles) either addressed a question specific to rural and/or remote health, or included findings on rural and/or remote health.

Table 3: University Departments of Rural Health Network peer-reviewed publications, 2013

Health services development

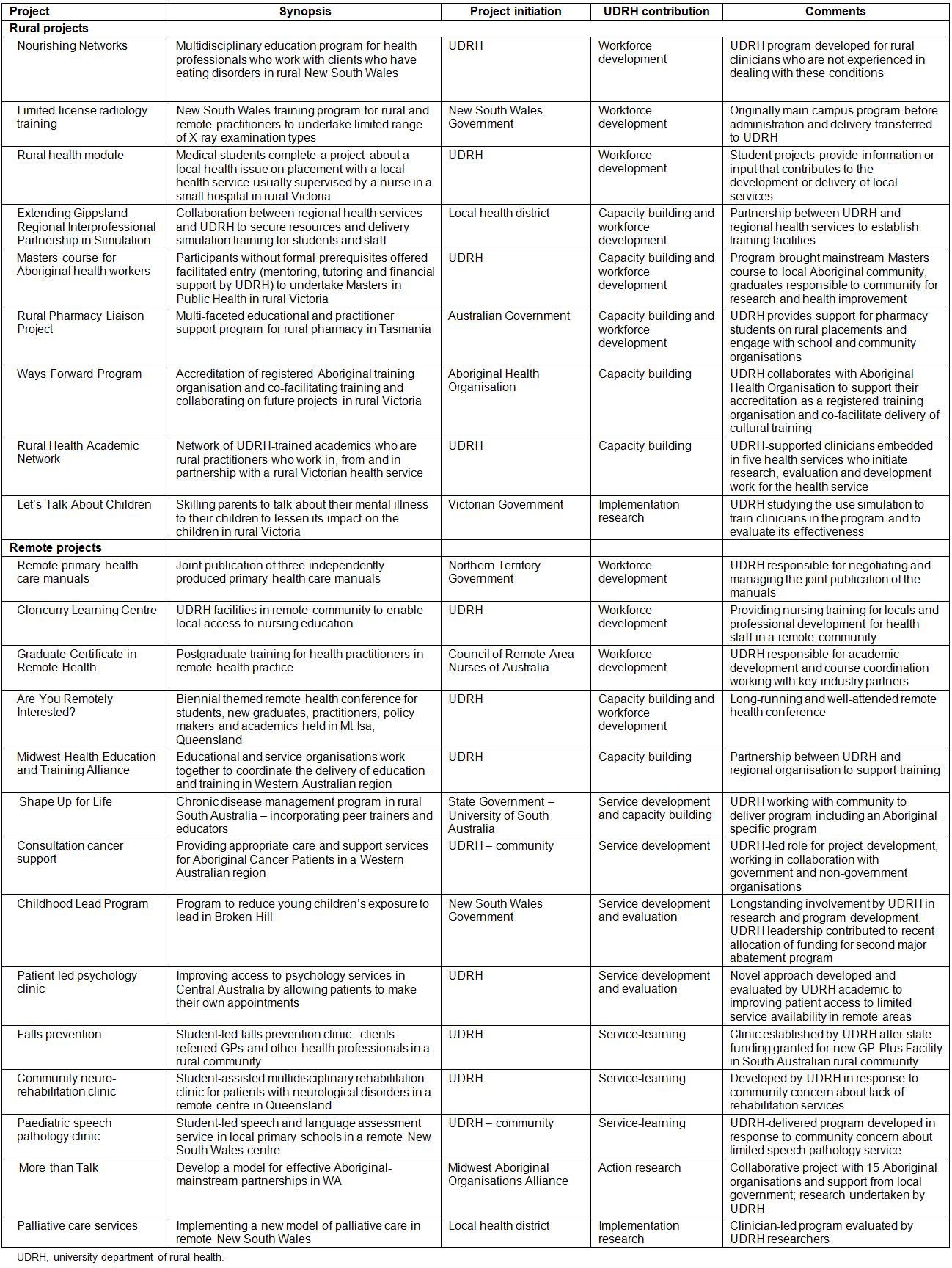

Table 4 provides examples of sentinel network projects that targeted priority rural and remote health issues within the UDRH catchments, some of which have been formally evaluated. They exemplify both UDRH investment and leadership in rural workforce and training development programs such as limited license radiology training14 and publication of remote healthcare manuals,15 health service development including patient-led psychology clinics,16 service delivery such as neuro-rehabilitation17 and speech pathology student-led clinics,13 and capacity building such as the Midwest Health Education and Training Alliance.18 Most projects were regionally based and responded either to government, health service or professional priorities, or community and clinician concerns. The UDRH contribution included academic services, support and infrastructure relating to research, evaluation, and education and training, as well as providing advanced expertise in service and organisational development, clinical services, and capacity building.

Table 4: Examples of University Departments of Rural Health Network projects that support rural and remote communities, 2009–2013

Discussion

This is the first detailed empirical analysis of the geographical coverage, activities, and outputs of UDRHs and the performance of the entire UDRH Network. It shows that the UDRH Network has established a strong and productive academic presence across rural and remote Australia.

In particular, the engagement of UDRHs with many health services and communities across 40% of rural Australia is a major achievement. The UDRH Network has offered enhanced rural clinical placements to nearly one in five domestic health students during their training. The relatively prominent student exposure (on a population basis) to ‘remote’ UDRH regions and the recent introduction of service-learning programs are particularly important, given that communities in remote regions often have the greatest health needs, the greatest shortage of health professionals, and most difficulty in recruiting and retaining a health workforce.

The effects of UDRH support varied among disciplines, with several major allied health disciplines benefiting through increased placements, while other disciplines, such as social work and psychology, continued to have limited rural and remote exposure. The UDRH Network, with its multidisciplinary orientation, complements and interacts with rural clinical schools, which concentrate on training medical students. The combination represents a carefully constructed system of rural health professional education and a significant commitment by the Australian Government to rural and remote health workforce development.

The UDRH Network has delivered substantial research outputs that are contributing to the rural health evidence base19, with approximately 40% of publications explicitly addressing a rural or remote health issue. Given the paucity of research publications relating to key rural and remote health issues prior to the establishment of the UDRH Network, this is an impressive output.20 Moreover, the fact that this research is being undertaken by academics and researchers based in rural or remote sites demonstrates the important role and contribution of local capacity building associated with the distributed locations of the UDRHs.

The significance of regional engagement of UDRHs is reflected in their contribution to local projects that develop new models of care relevant to identified needs, improve access to services, support better-trained health professionals, and build capacity in rural and remote organisations and communities to effectively respond to the health challenges in context. These strong local partnerships help to ensure that health services are better able to respond in the delivery of appropriate health care that meets community needs and minimises the need to travel long distances.

The present analysis links the success of the UDRH Network with the principles of the national strategic framework for rural and remote health: partnerships and engagement, local solutions, and a strong evidence base.21 The intent of the UDRH Network also accords closely with the findings of the strategic review of health and medical research in the health system through investment in teaching and research, the integration of teaching and research with clinical practice, and the development of health professional research capacity.22 At the same time, the activities of the UDRHs continue to meet the very different and distinctive needs of the respective populations that they serve.

The annual investment in 2013 of $50 million in the Australia-wide UDRH Network seemed well justified by the network’s productivity, student throughput and coverage. However, comprehensive and reliable information is lacking on the extent to which this investment is promoting the uptake of rural or remote practice after graduation or improving health outcomes. This is the key question. Finding a definite answer is difficult because many factors affect health professionals’ career choices. The available evidence indicates that first-hand experience of rural or remote health care in education and training is a critical formative component that engages individuals and ultimately leads to a resolution of rural and remote health workforce shortages.23

The recent additional funding from the Australian Government to increase training activity in the existing UDRHs and the establishment of three additional UDRHs in 2017 place greater emphasis on the need for ongoing monitoring of performance of the UDRH Network as it grows, with an expectation that more than 40% of nursing and allied health students will be offered a UDRH-supported clinical placement in the near future. The data presented here could assist in benchmarking performance for the new Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training Program as the Government moves to better align the UDRHs, and the approaches adopted within the UDRH Network, with the rural clinical schools.

Conclusions

Since their inception 20 years ago, UDRHs have become well-integrated entities, effectively embedded within their regional communities. The UDRH Network now operates across a substantial footprint and, on the available evidence, fulfils an essential academic role for the health system in rural and remote Australia. The present evaluation shows that UDRHs are making a difference based on an assessment of geographical coverage and activity, relevant contribution, and engagement in rural and remote communities. As the UDRH Network approaches a new phase of its existence, the next stage of evaluation should focus on providing evidence on the specific workforce, health service, and population health outcomes.

Disclosures

The authors declare the following possible competing interests:

- Professor David Lyle is Head, Broken Hill University Department of Rural Health; member ARHEN Board.

- Ms Veronica Barlow is an employee of Broken Hill University Department of Rural Health.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by a grant from the Australia Rural Health Education Network (ARHEN). The authors acknowledge the cooperation of ARHEN and the UDRH Network in completing this project, and Michael Frommer for reviewing the manuscript. The Monash University School of Rural Health–Bendigo and the Broken Hill University Department of Rural Health, University of Sydney are funded by the Australian Government Department of Health.