Introduction

The lack of health facilities, the rising cost of health care and the difficulty in accessing quality health care for rural communities put these communities at risk for poor health outcomes1. To sustain rural communities, the health of young rural residents becomes a priority. To address the healthcare needs of rural communities, it is important to understand what contributes to health, chronic disease and conditions, and what is necessary health care. Health and illness extend beyond the biomedical to include the psychological and social dimensions, as illustrated by Engel’s psychosocial model2. All three dimensions – biological, psychological and social – need to be considered as parts and as a whole, implying that each domain in itself and all domains as a group are central to understanding and promoting health.

Considering the differences, especially in the social domains of urban and rural life, healthcare delivery systems developed for urban communities may not meet the unique contexts and needs of rural communities. Studies have found that perceptions of health-related behaviors differ between urban and rural adolescents concerning alcohol abuse and methods of interventions3. To develop strategic health programs and effective, health-promoting policies for rural adolescents, the personal perspectives of adolescents about their health and health needs should be understood and incorporated into health services, health education and health policy4. Studies examining the health concerns of rural adolescents have primarily utilized surveys that do not capture personal perspectives of adolescents5. There is a need for qualitative studies that capture the personal views of adolescents. This study utilized focus groups to elicit the personal views of rural adolescents.

Health vulnerability of rural adolescents

Rural adolescents are a highly vulnerable group. Studies have found that alcohol and drug use, pregnancy and STI rates are high among rural adolescents6,7. Poverty, substance abuse, and lack of employment opportunities, transportation, education, health services and health insurance associated with living in rural areas increase rural adolescents’ vulnerability to health issues8. Studies have found that compared to urban adolescents, rural adolescents have higher rates of use of alcohol, cocaine, methamphetamine, and inhalants, and are more likely to engage in dangerous behavior such as binge drinking, heavy drinking and driving under the influence7. Rural adolescents are particularly vulnerable to the availability of marijuana because of the ability to produce the substance in rural regions and that more follow-up intervention after treatment is completed is required than with urban adolescents9.

Rates of adolescent (ie 15-19-year-old girls) childbearing in 2015 in rural USA was two thirds higher (30.9 per 1000) than in urban USA (18.9 per 1000)10. Educating and engaging adolescents on sexual health topics may not only curb unplanned pregnancies, but may also decrease STIs. Adolescents represent only 25% of the sexually experienced population yet acquire nearly 50% of all new STIs6. Barriers to accessing quality sexual health services include lack of health insurance or ability to afford, lack of transportation, discomfort with facilities, lack of adolescent-friendly services and concerns about con%uFB01dentiality11.

Adolescents’ health status can also be gleaned from overweight and obesity rates. In Kansas, 30.9% of 10-17 year olds were found to be either overweight or obese in 2016, making Kansas the 25th highest US state for most overweight and obese youth12. While data on rural Kansas youth are not available, obesity rates among adult residents in Kansas was reported to be 31% in rural areas compared to 27.8% in urban areas. Poverty rates, education levels and lifestyle differences in rural compared to urban settings were cited as the main contributors to this disparity12.

Rural adolescents also face challenges with mental health because more than 85% of rural residents live in areas with shortages of mental health professionals13. Per capita rates of behavioral health professionals in urban areas are 1.6 times more than in rural areas14. The shortage of mental health professionals means that 65% of rural residents receive mental health services from their primary care physicians14. Subsequently, rural residents are more likely to use pharmacology than psychotherapy to treat mental health disorders.

Many rural adolescents will remain underserved and without primary or preventative care due to an inadequate number of health providers. It is estimated that an effective and efficient physician-to-population ratio is 1:120015. In the USA, for primary care physicians that ratio is 1:1300 in urban areas and 1:1910 in rural areas. For family physicians, that ratio is 1:2940 for rural areas. Given the poor health outcomes of rural adolescents and the lack of information to develop strategies to improve rural health care, this study aims to elicit rural adolescents’ personal views on health and health care.

Methods

To better understand rural adolescent health, this study was conducted in Kansas, where 72 geographic health professional shortage areas and 97 mental health professional shortage areas were designated by the governor16. These areas have a ratio of population to primary care physician of ≥3500:1, and a ratio of population to psychiatrist of ≥30 000:1. A qualitative approach was utilized to obtain the opinions of adolescents and elicit their personal perspectives on health care.

Participants

Participants were 65 adolescents from four rural counties, defined as having 6-19.9 persons per square mile. Six focus groups were conducted with 8-15 adolescents per group. Adolescents were 13-19 years old (mean=15.83, SD=1.31); 18 males and 47 females; 54 White, seven Hispanic, one Black, and three multiracial.

Data collection

The research team included faculty and graduate and undergraduate students. Research and Cooperative Extension professionals and public health directors residing in the target communities helped with recruitment and scheduling of the focus groups. The adolescents who participated in the focus groups were recruited by community-based organizations such as schools, 4-H clubs, faith-based groups, and out-of-school organizations in geographic locations selected by the funder of the project. The individuals conducting the focus groups were trained in a graduate couple and family therapy program. Focus group sessions were audio recorded as well as typed by a trained transcriptionists as the focus groups were being held. Analysis was conducted of audio-recorded transcripts as well as typed transcripts.

Focus groups were asked:

1 ‘What do you consider to be the most important health issues for teens today?’ [This is where we try to see what teens think are the most important, pressing health issues.]

2 ‘What do you think are gaps in health services for youth?’

3 ‘What barriers or challenges do you or your friends face that keep you from being healthy?’ [Peer pressure/peer influence. Cost of healthy options? Do they have a doctor, provider, insurance? Is lack of information or embarrassment a factor?]

4 ‘What recommendations or suggestions do you have to address these barriers or challenges?’

5 ‘Is there anything else you want to say about adolescent health or your experiences related to health services for adolescents?’

Each group met once during either in-school or out-of-school class sessions, or club meetings. Groups were informed that no answer was wrong and that personal input was sought to enhance health services and programs for the community. Semistructured questions asked pertained to health issues adolescents faced, ways to address these health issues, and gaps and barriers to receiving services. Discussions that were audio-recorded and transcribed for analysis averaged 45 minutes per group.

Data analysis

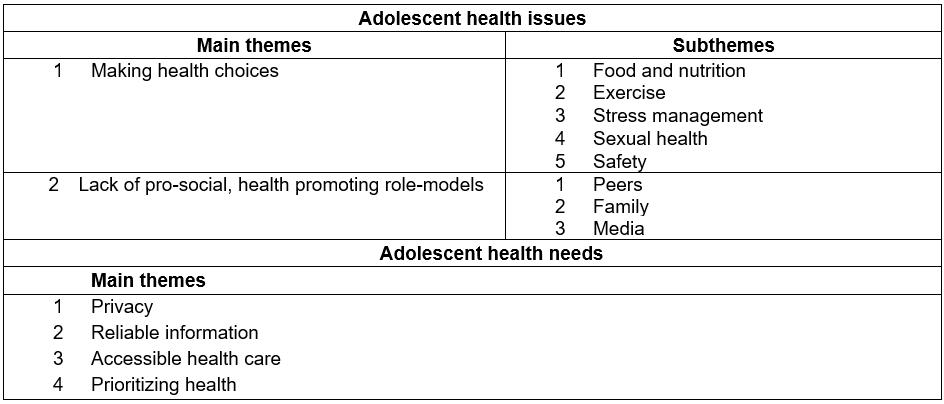

Grounded theory guided the analysis of focus group transcript content to identify overarching themes. The process included three levels of coding – open, axial and selective17. Open coding involved identifying and categorizing data at a basic comparative level of line-by-line analysis18. Axial coding identified relationships and connections between established open codes. Once core categories began to emerge and no new categories surfaced, selective coding began where data relevant to the emergent categories were identified. Related concepts were combined to form subthemes within main themes (Table 1).

Data were analysed by two researchers to help ensure confirmability and dependability of the findings19. Transcripts were analysed via open coding separately by each analyst. After analysing the first transcript, both analysts met to converge their findings. Differences of opinions that arose were discussed until consensus was met. Relationships and connections between open codes were identified and collapsed together to form the initial set of broad themes. This same process was repeated for the second transcript. Thematic findings from the first and second transcripts were then combined. This process of comparing and contrasting across transcripts, known as triangulation, helped ensure the credibility and trustworthiness of the findings19. The same process was used on all subsequent transcripts. Upon completion of axial coding, selective coding ensued. The themes, subthemes and excerpts from the transcripts are presented below.

Table 1: Themes and subthemes

Ethics approval

Kansas State University Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for this study entitled ‘Kansas adolescent health needs assessment and strategic plan pilot project’ (approval number 7208). While parental consent was waived, adolescents gave their consent to participate in the focus groups.

Results

Two themes reflected adolescent health issues – making healthy choices and having poor role models – and four themes reflected health needs – privacy, reliable information, accessible health care, and prioritizing health. Barriers that prevented health-promoting practices included the lack of adults as role models for positive health practices and promotion. The lack of privacy impinged on the willingness of adolescents to seek healthcare services. The absence of reliable health information and inaccessible health care made prioritization of health a challenge. These findings were consistent across all focus groups.

Health issues

Making healthy choices: There was awareness among the adolescents for the need to learn how to manage their own health and that choices and perceptions directly influenced their health. Despite this realization, making healthy decisions related to diet, exercise, stress management, sexual health, and safety was a challenge.

Food and nutrition: Access to quality, appetizing food was discussed in all six groups. Poor food choices were related to the preference of spending time with friends over spending time, money, and effort to seek out healthier food options, and the convenience of non-nutritious food:

I have to eat, but I have no time to fix food, so I get whatever’s in the fridge, and that’s not usually healthy [laughs].

School lunches were a major contention; specifically, the lack of ample food made many participants miserable due to hunger:

They don’t give us enough because we’re going through growth spurts and hormonal changes. We’re all like mentally unstable because we don’t know what’s happening with our bodies, so we need more food.

This hunger led to poor dietary choices after the school day, described as ‘pigging out’. This behavior, however, seemed to be reasonable considering that many of the youth had work responsibilities/chores on their family farms that was labor intensive and required more calories:

… a lot of us do sports then go home and work on a farm so we work it off, and like that 800 calories does not stick with you, so there has to be something more for us, I don’t think that’s a way to solve the obesity problem.

The magnitude of farm responsibilities and the lack of time it afforded at the end of the day was noted as a major challenge in preparing healthy meals:

We don’t have a whole lot of time to make it home and eat something … and the unhealthy stuff is what’s quick and easy. We’re gonna eat what’s available. I only have a half an hour to eat dinner and do homework, I’m gonna do it as quick as possible.

Exercise: There was consensus that exercise was beneficial to health. A barrier to exercising was the inability to access facilities without an adult:

We have a weight lifting room at school … but we’re not allowed to go into it (by ourselves) because of insurance reasons.

Not having transportation was another barrier:

We could go to [a nearby town] and swim … during the winter months but we can’t do that … we can’t drive!

Perceived judgement of others was another barrier cited:

Judgement, like, ‘Oh you have to work out because you’re fat’. You can’t just work out because you like to work out, it makes you feel good. Like, people think, ‘Oh she just works out because she’s fat or oh she thinks she’s fat’. Like, I’ve gone on like four runs now and every time, like at least ten, twenty people … break their necks to look.

Despite the fact that most were engaged in physically strenuous work on family farms, there was an understanding and appreciation for recreational forms of exercise pursued for pleasure and relaxation. There was a concern that the lack of facilities in local communities meant boredom for many adolescents. Many expressed the belief that boredom led to substance abuse, drinking and driving, and risky sexual activity.

Stress management: Managing the stress of juggling multiple roles and accompanying responsibilities – as student, athlete, employee, farm help and caregiver to younger siblings – was a major challenge for many:

If you live out of town it’s super hard, very hard if your parents work late at night in the city, and I’m like, ‘Crap, I have to get food for me and my little brother’. So you’re trying to take on your parents’ responsibility.

The common stress of trying to ‘fit in’ with peers was as problematic as stress from cyber-bullying that often targeted body image. Over-indulgence on unhealthy foods, use of substances, and self-harming behaviors, including suicide, were attributed to the inability to manage stress from bullying:

Yeah, it [bullying] can lead to suicide, because it’s stressful and can lead to killing yourself or lead to them killing someone … it [bullying] could lead to someone starving themselves and eating disorders.

In several groups, adolescents discussed having to manage chronic illness, such as diabetes, epilepsy, and ADHD, for themselves, a friend, or a sibling. How their own sense of helplessness in managing illness burdens peers and teachers was also an expressed concern:

I have like thyroid [and] diabetes. There’s been days when I’m just really low and don’t know where I’m gonna be able to get a snack. If it comes down to an emergency, they [friends] couldn’t get me something from the kitchen. I mean it adds stress to my life. Like, not knowing if I will be able to find a snack, but also my friends, they know they have to deal with it, they want to be there to help … It causes stress to teachers too.

There was an overall perception that managing stress well would lead to success in school while attempting to buffer stress with substances was an escape that would lead to poor academic success. There was a clear desire to succeed in what was considered to be attributes of a normative lifestyle.

Sexual health: There was concern voiced for not knowing the consequences of sexual intercourse and fear of seeking medical treatment for sexual issues:

[sexual activity] could lead to physical health issues too because what if, you know, what if she got something, such as a disease, or a child.

The pressure to be ‘cool’ and lack of sex education were noted as contributors to unprotected sex:

Just a lack of sex education. People don’t know how to be safe … if they were to have a problem I don’t think they would know where to go, or who to talk to. They would just kind of ignore it … and might end up with some health issue, infection or child.

What may be a barrier to seeking health care was the gendered standards and labels pertaining to sex. Not surprising, it was more socially acceptable for men than women to have sex: ‘If a guy (has sex), he’s cool, but if a girl (has sex), she’s a slut.’ Labels such as ‘slut’ prevented women from seeking help while men were only interested in having sex but not sexual health care.

Safety: As expected, due to normative risk-taking behaviors, there was a sense of invincibility among the adolescents that made taking risks and jeopardizing personal safety a non-issue for many: ‘A lot of people just don’t think it’s going to happen to them’. Discussions of safety revolved around how perceptions of invincibility and focus on immediate gratification may explain poor health choices, especially when attempting to cope with boredom. There appeared to be a general understanding that developmental stage explained the inability to control impulses – creating a perception that the immediate benefits of risky behaviors outweighed potential consequences. Interestingly, while looking for an excuse for the poor health choices, insight into reasons for risky behaviors was gained.

Lack of pro-social, health-promoting role models: The deficiency of healthy role models emerged as a pertinent health issue. Potential role models lacked skills, education, and resources to maintain health. Models for unhealthy behaviors were easily available in peers, family members and media: ‘We learn to do alcohol and drugs from our older siblings, friends, and parents’.

Peers: There was pressure to fit in by engaging in unhealthy and sometimes risky behaviors:

When I was with my friend one time, we were walking and he pulled out a can of chew[ing tobacco], and started putting it in his mouth and handed it over to me and said ‘Do it’. And I said I didn’t want to do it, and he said, ‘Come on it’d be fun’. And he was peer pressuring me.

The desire to be accepted by peers and maintain friendships was noted as reasons for falling prey to pressures to conform. The prevalence of such risky behaviors such as underage consumption of alcohol made them common and acceptable practices over time: ‘People have shown up drunk to school before’. Interestingly, there were no discussions pertaining to pressures to practice health maintenance.

Family: Parents were often cited as partaking in risky behaviors such as supplying alcohol, hosting parties with alcohol for adolescents, and texting while driving. These behaviors were perceived as confusing and made it confusing for adolescents to adhere to advice given by parents themselves who fail to ‘do as they preach’:

When my dad’s driving sometimes he’ll be like on his phone. Well if … I was on my phone you would tell me to get off, so why don’t [my dad] get off your phone.

These double messages from parents led to unsuccessful re-directing of their children. In addition, if any re-directing were to happen, it appeared to resemble bargaining:

Recently my stepdad found out that [my stepsister] partied, had sex, she drinks, she smokes weed, smokes cigarettes. I think a big part of it is that parents or guardians aren’t stopping it you know, aren’t cracking down on it. So my stepdad gave my stepsister an option for her to stop smoking weed if she smokes cigarettes … Since she’s not 17, he’d pay for [cigarettes].

There was concern that parents’ inability to re-direct would have consequences for children who observe and attempt to follow the confusing interactions.

Media: The negative influence of objectifying women in mass media and how this could influence self-esteem was a topic discussed. The illusion of the ‘perfect bodies’ portrayed in magazines, music videos and film was noted as the cause for people to think that their bodies were not ‘good enough’, which could lead to unhealthy eating practices. Risky behaviors were also attributed to consuming media that promoted such behaviors:

… pop music … references are about like objectifying women, drugs and alcohol abuse. You know, partying … that’s what it’s all about, and that’s what people listen to, and it’s stuff teachers are saying don’t do.

When asked how they acquired health literacy, many said they relied on online resources. While those resources were cited as helpful, there was awareness of the risk of being misinformed, which could lead to dangerous health practices. The complexity of deciphering the vast amount of information on the internet was described as daunting:

… like you can Google something and you’ll have 40 different diets pop up – like this celebrity’s doing this so you can look like her and everyone believes it for whatever reason. So who do you believe?

Health needs

Privacy: In each focus group, there was a unanimous desire for privacy. The small size of rural communities impinged on privacy and prevented the simple act of walking into health clinics:

It’s not as easy for you to walk into a place by yourself and be like, ‘Uh, I don’t know if I’m pregnant or not but I’d like you guys to check me out’. You can’t do that … well you could but we’re in such a small town, it would get right back to your parents immediately.

Embarrassment about being known for needing services, especially for sexual and mental health issues, was a main reason for not seeking help. The lack of privacy also influenced the procurement of health-related supplies such as contraceptives:

They might be embarrassed to buy [condoms]. If I was a guy I would be very embarrassed to buy that from the store. I’d go to like one of the little quick shops and go into the bathroom … they have [condom dispensers] in some bathrooms.

The fear of being judged for seeking health care was noted as one reason for turning to the internet. This, however, was coupled with the fear that any information sought, whether from health professionals or the internet, would be known by parents. The possibility of losing parental favor if parents knew of their health needs was a concern:

You don’t want [parents] to think differently of you. Your parents might make you feel unwanted or they might dislike you.

There was a belief that if parents and teachers had confidence that adolescents could be responsible for their own health, there would be more privacy in seeking health services. The necessity for parents’ or care providers’ permission to access health care was cited as an impediment to health. To have the necessary privacy and independence to access health care would first require the adults’ trust.

Reliable information: There was a pervasive call for accurate health information from educators and parents. Although information is available on the internet, there was concern about its reliability, and instead of fictionalized accounts, stories of real life experiences from trusted adults were preferred:

We want people to ‘be real’ with us. Tell us about the real life-threatening consequences of teen pregnancy. Teens need to know what it’s really like to have a baby. What it’s really like to have an STD.

There was, however, a preference for peer educators:

If it’s a 40 year old guy talking about [health issue] … some of us are going to pay attention, but most are gonna be like, ‘He’s too old for us’. If it’s a teenager that comes in and says, ‘Listen, these things can happen’ … I’m gonna listen and say, ‘Wow, I am not invincible’.

What seemed to be valued were frank conversations with trusted adults on relevant health issues. It was apparent that the perspective of adults, especially parents, was valued. There was a desire for deep, meaningful, and ‘real’ conversations with adults and care providers about topics that were considered uncomfortable to discuss. There was faith that adults would know and be able to guide and help decipher the vast body of information available if adults were accessible

The discussions among adolescents that took place during the course of this study allowed for the sharing of experiences and were viewed favorably. Some adolescents suggested that a similar setup could be used to disseminate health information:

More, like, teenage-friendly conversations among adults like these [patted hand on table referring to focus group discussion] … respectful mature topics like, no like, dancing around the subject. Like tell us … we need to know.

The lack of education and being told to not partake in certain unhealthy behaviors was frustrating. Instead, the request was for factual information and no coddling or shielding from the realities of life.

Accessible health care: The challenges of accessing health care resulting from geographical distance from health providers and lack of affordability was voiced along with suggestions to alleviate the cost and inconvenience of seeking health care. While distance to health providers, especially medical specialists, determined the frequency of seeking services for some, others thought that technology and the internet could reduce the need for health centers if home remedies were used instead. Online communities that share home remedies for common ailments appeared to be an acceptable alternative to seeking health care from a trained, licensed and certified medical practitioner. Healthcare services within schools was believed to be a way to allow access to bona fide health care.

The cost–benefit analysis of health care was thought to factor in decisions to seek medical treatments and preventive health care. An adolescent who endured a broken wrist for 7 months alluded to the fact that the cost of health care may potentially prevent or delay seeking services:

I know everybody can’t afford to go to like yearly [medical] checkups ... I know for the office in town, I think it’s like $80 per office visit. At least the doctor I would go to … that’s with insurance, good insurance. So I don’t, I don’t know if people don’t go to the doctor a lot because it’s not worth it to go right away. So you don’t go to the hospital for three months. Like, my wrist was broken for seven months.

In addition to the cost of health care, resources that can help achieve and maintain good health, such as healthy foods, were noted as being unaffordable in many rural communities. The often monopoly of a sole grocery store in town made food security a real concern for many:

Healthier foods are really expensive compared to like Burger King or whatever ... Like to stay healthy and in a small town like this there’s only one real place to get food and so one place that can drive up prices.

Prioritizing health: There was a need to prioritize a healthy lifestyle that included preventative care. The lack of positive role models for how to prioritize health was noted as a challenge to even knowing how to make health a priority. There was consensus that healthy options existed, but convenience not health promotion often won out. Although there was a clear understanding of the potential risks of using substances, being sexually active, unhealthy eating, and living increasingly sedentary lifestyles, the risk to feeling gratified through unhealthy or risky behaviors even for a moment prevailed. The long-term consequences of the adolescents’ choices were not a consideration. Interestingly, perceived laziness and wanting to make health choices easy were cited as other reasons for not prioritizing health:

I could go run on my treadmill or I could … spend three hours on my phone on social media and sit there like in laziness. (I) like, the easy way out, that’s really what the big problem is. You don’t ride your bike because it’s the easy way out. You take drugs to make you feel better because it’s the easy way out.

Being aware of the need to prioritize health did not equate to doing so due to the absence of examples of healthy role models in their communities.

Discussion

This focus group study eliciting rural adolescents’ views of their health issues and needs may provide important information that can help mitigate some of the obstacles to accessing and providing appropriate health care in rural communities for youth. The findings illustrate the complexity of adolescent health that goes beyond the inability to access health care and nutritious food. The biopsychosocial model3 that considers the social context of living in areas lacking exposure for the community and where the stigma of seeking health care is prevalent provides a more holistic view of rural adolescent health.

The factors that contribute to adolescent health in rural settings reside in the communities themselves. Common features of rural settings are familiarity and close-knit communities, though integral to developing a sense of belonging, can be impediments to privacy20. Lack of exposure and reputable resources to educate young people may instigate biases against those who are not well – mentally or physically21. Biases can lead to the stigma associated with seeking health care as alluded to by the adolescents in this study. Stigma leads to distancing and fear promotion, making it difficult and at times impossible for adolescents to seek the care they need20. Adolescents who need sexual/reproductive and mental health care seem to be the ones most fearful of seeking services. So even if appropriate healthcare services are made available and accessible, the lack of privacy that is often imbued in rural communities may likely prevent adolescents from benefiting from those services.

Another factor that needs to be considered is the nature of adolescence and how this period of development influences overall health. It is acknowledged that adolescence is a time of tremendous change and identity seeking22. This phase includes a high level of curiosity and with that risk-taking as young people differentiate themselves. It appears that traditional forms of education may not be obsolete. Interestingly, the rural adolescents in the study knew that not all information – especially information available on the internet – is reliable. Perhaps the cultural method of story-telling used to pass on teachings from one generation to another is what rural adolescents yearn for and value. Sharing life stories is one of the key strategies for expressing wisdom that contributed to growth for both story-teller and recipient23. Contrary to general perceptions that adolescents do not want interaction with or involvement of parents, adolescents in this study desired connection with their parents and adults in general24. The call by adolescents for ‘frank’ discussions about stress management, consequences of substance abuse, realities of adolescent pregnancy and the importance of sexual health point to adolescents’ longing for factual health anchored in the experience of trusted adults. It is through open dialogue and frank conversations with adults that adolescents believe they would best access the type of health information they need. The difficulty in accessing the internet in rural Kansas may be an impetus for the request for in-person dissemination of information. Internet access can be costly in rural areas due to the lack of competition. Twenty-one percent of Kansas households are considered to be underserved with fewer than two internet providers available25.

However, even when armed with accurate information and the options to improve their wellbeing, adolescents may make choices that contradict their desires to be healthy. Making poor choices is a feature of adolescence – a period of exploration, carving out a unique identity, succumbing to peer pressure and an inability to fully determine what is helpful or harmful. What seems to augment these poor choices is a lack of positive role models. Adolescents look for role models in their parents, siblings, peers and community24. The absence of positive role models means adolescents lack guidance at an age where they are highly impressionable and when their overall health can be affected for their lifetime.

Though a limited workforce and the overextension of farm families may be routine in rural communities when the daily reality for most rural adolescents is filled with part-time jobs, assigned homework, household and farm chores, little time is left for reflection and healthy extracurricular school activities. Mindful awareness, reflection and attuning to one’s self are essential practices to cultivating resilience, empowerment and improving wellbeing26. Hard work is valued in rural communities and is often viewed with pride, but in the context of rural adolescents, this is synonymous with being over-extended and stressed and leading to decisions based on convenience and immediacy.

Rural schools are often the proverbial ‘beating heart’ of small communities and a center for familial activity as well as the primary location where adolescents congregate. School-based access to confidential mental health screening, referral, and treatment that reduces the stigma and embarrassment often associated with mental illness, emotional disturbances, and seeking of treatment must be established. The systemic nature and inter-connectedness of the findings point to a need for greater collaboration with school systems to provide access to not only mental health services, but medical, dental, nutritional healthcare and social services as well. Schools can strategically begin with one component of health to make a significant contribution. For instance, helping adolescents make healthy food choices improves physical and mental health27 – a link that was discovered in a systematic review of 12 epidemiological studies. A recent study that reviewed school and community-based interventions noted that schools can be effective agents for promoting mental health interventions to low and middle income groups28.

Rural healthcare providers, who are notably ‘few and far between’, could benefit from collaborating with schools and communities to relocate services to ease access and increase availability. Communities need to develop more integrated health care that not only provides prevention, early intervention and treatment for adolescents, but also includes adolescents in the planning. Such involvement would give adolescents ‘voice’ and give them some investment in the creation and development of services. Research on adolescents’ health experiences and literacy should continue to include adolescents’ ‘voice’ to inform health interventions, delivery and promotion. All adolescents, not only rural adolescents, can benefit from being empowered when their opinions and voices are heard.

The findings of this study point to the need for accessible and affordable health care in rural communities. Having mobile health clinics visit schools regularly may be a viable option. The physical and financial feasibility of mobile clinics that conduct health assessments and provide treatment should be studied. Research should include identifying prospective schools, evaluating the feasibility of resource allocation, and developing a prototype clinic to run trials.

There are limitations to the present study. Specifically, this study only included densely populated rural locations, so extending these findings to frontier locations needs to be done with caution. Also, in the attempt to provide flexibility, three focus groups had more than the recommended 6-10 participants. Large focus groups can prevent shy participants from speaking up and they may agree with the viewpoints of more outspoken participants. In addition, schools were not the most conducive location for these focus groups due to interruptions that commonly occur – such as announcements over the intercom or teachers entering the room at the beginning and end of the focus groups. Last, given that the participants were predominantly females (72.3%), the findings may not reflect the views and experiences of male youth.

Conclusions

The healthcare needs of rural adolescents are compounded by their unique socio-environment and the involvement of multiple systems – family, school, peers and healthcare providers – rooted within rural communities. Though rural communities offer many positive, quality-of-life attributes, they may afford limited opportunities for young people and may prevent adolescents from becoming thriving, contributing citizens. It is crucial that communities seek to hear, strengthen, and empower young people through education, sharing of personal experiences and struggles, protecting their time and channeling their energies, and by providing positive role models. Attaining and maintaining good health is a lifelong process. Learning how to be healthy takes time and effort. Communities that lack recreational resources that can offer the ‘down time to unwind’, to engage in healthy activities and to re-energize do a disservice to their adolescents. The lack of healthy forms of recreation can lead to boredom, and consequently engagement in unhealthy activities and risky behaviors.