Context

This article describes Memorial University of Newfoundland’s Faculty of Medicine (hereafter referred to as Memorial) rural-focused medical school program to provide an in depth look at how Memorial’s faculty of medicine is achieving its social accountability outcomes related to producing rural doctors for its region (Newfoundland and Labrador, NL) and nation (Canada) as reported in the companion paper ‘Does rural generalist focused medical school and family medicine training make a difference? Memorial University of Newfoundland outcomes’1.

Physician retention in underserved and rural areas is challenging, including in NL, Canada’s eastern most province2-4. The literature describes key interventions to increase the number of rural doctors. These include admitting more rural-origin students to medical schools, providing more medical school education in rural communities, and providing rural-focused postgraduate vocational training4,5. These optional but interdependent variables are linked together in what has been described as a ‘pipeline to rural practice’.

The term ‘pipeline to practice’ was used as early as 1998 in the 10th Report from the Council on Graduate Medical Education, where a potential solution to ‘rural geographic maldistribution’ was described (see Box 1)6.

A number of pipeline to practice ‘stream’ programs have placed interested students from rural backgrounds into a rural-focused learning stream, achieving excellent outcomes. Early examples include the University of Minnesota–Duluth’s Rural Physician Associate Program (RPAP)7,8, Jefferson Medical College’s Physician Shortage Area Program (PSAP)9,10, the University of Missouri School of Medicine Rural Track Pipeline Program (MU-RTPP)11,12, and the Rural Health Leaders Pipeline at the University of Alabama13,14.

Flinders University (South Australia) created the Parallel Rural Community Curriculum (PRCC), which provides opportunities to learn all clinical disciplines in an integrated way rather than in conventional clerkship block rotations. This longitudinal integrated rural stream program is an optional choice for Flinders medical students15,16 and provides a model that is being adapted by medical schools worldwide.

Memorial, like other Canadian medical schools, is a graduate-entry medical school. It provides medical degree (MD) education (paradoxically referred to as undergraduate) accredited by the Committee on the Accreditation of Canadian Medical Schools/Liaison Committee on Medical Education (CACMS/LCME), vocational residency training programs (postgraduate) accredited by the College of Family Physicians Canada (CFPC) and the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (RCPSC), and accredited continuing medical education (CME: professional development for practicing physicians).

The first part of this article describes programs, interventions and initiatives related to Memorial’s rural-focused medical school program starting with Before Medical School (MedQuest, Aboriginal Initiatives, Admissions), MD Education program (Pre-clerkship, Clerkship, Electives and Selectives), Postgraduate Vocational Training (Family Medicine Residency Training Program), and After Medical School (CME/PD). The second part of this article using the same sequential flow provides a geospatial rurality analysis of administrative data collected upon entry into and during the MD program and postgraduate (PG) training (Learners & Locations (L&L) database) to highlight rural-focused initiatives.

Box 1: Pipeline to practice solutions for rural communities according to the Council on Graduate Medical Education4.

Programs/interventions/initiatives

Memorial pathways to rural practice

Memorial is a rural-focused medical school that provides MD education and PG vocational residency training programs directed towards the healthcare needs of NL and Canada. This social accountability focus remains as relevant now as it was during the medical school’s establishment in 196717-19. Memorial’s pathways to rural practice has several interconnected components that begin before a student is admitted, follows them throughout their MD education and keeps up with them during their postgraduate training and clinical practice.

Before medical school

Memorial’s ‘pathways’ approach begins before the student is admitted into medical school. Memorial’s pre-medical school initiatives include the MedQuest program, Aboriginal initiatives and an admissions process that strives to be inclusive and representative of all segments of NL’s population.

MedQuest secondary school outreach: MedQuest was founded in 1990 as a high school outreach program designed to expose rural students in the province to medicine and other health professions as potential careers, on the premise that rural students are more likely than their urban counterparts to pursue health-related careers in a rural area. Currently, the program consists of six 1-week sessions during which students live on campus and benefit from hands-on experiments, lectures, Q&As, and tours of health facilities. Now in its 24th year of operation, MedQuest has seen 3400 participants from across the province20.

Aboriginal initiatives: Memorial’s Aboriginal Initiative was established in 2008 to coordinate and establish programs to increase the recruitment of Indigenous (officially Aboriginal in Canada) students to medical school and improve the understanding of Indigenous health by all students. Through this initiative, Memorial has established Aboriginal recruitment components that include school visits, the Healers of Tomorrow Gathering, MedQuest (with designated seats for Aboriginal secondary students), the Pre-Med Summer Institute, the Pre-Med Orientation and Mentorship Program, and the Medical College Admissions Test (MCAT) Preparatory Grant as well as three Aboriginal-pathway-reserved MD program seats. During medical school, Memorial offers mentorships, the Memorial Friendship Circle, and specific Aboriginal health sessions designed to address the core competencies developed by the Indigenous Physicians’ Association of Canada, which focus on the wellbeing of First Nations/Inuit and Métis peoples and the role that future physicians can play in building healthy communities among these populations21.

Admissions: Memorial’s MD education program admissions process reflects the goal of producing a diverse class that represents the population and will produce the best doctors for the future. This aligns with the future medical education of Canada MD report recommendation #2, ‘Enhance Admissions Process’22.

The Admissions and Interview committees include representatives from Aboriginal communities, rural communities, the general public, allied health professionals, medical students, clinicians, biomedical scientists, university, administration, the provincial medical association and provincial departments of health. The diversity statement23 reflects Memorial’s commitment to meeting the province’s healthcare needs through three priority areas: Aboriginal Peoples of NL; students from rural and remote areas; and economically disadvantaged students. Memorial’s inclusive and holistic admissions approach results in decisions based on a number of assessments, including academic history as well as personal characteristics, including educational, socioeconomic and geographic background. This approach recognizes the different levels of students’ access to opportunities and the resultant effects on academic performance and other aspects of their medical school application.

MD education program

The MD education program is divided into two major parts: the first 2 years (Phases 1, 2, 3) are pre-clerkship and the final 2 years (Phase 4) are clerkship/preparation for residency training. The new curriculum, introduced in 2013, conceptualizes this further with a story-based spiral curriculum that sets much of the patient–family context in a variety of rural and regional communities, reflecting the distributed population and health determinant challenges of NL.

Pre-clerkship: In addition to determinants of health, the majority of educational placements focus on providing community-based experiences in which students experience first-hand the community’s healthcare needs. There are two 2-week placements, including an exclusively rural first year, a Community Health rotation where students are matched with a rural family physician preceptor who coordinates community experiences and half days in clinic. This course gives students early exposure to the broad health needs of the rural community in a primary care context.

Clerkship: Memorial’s flexible clerkship is designed so that students spend some or all of their training outside the tertiary care center in St. John’s. While all clerkship rotations (surgery, obstetrics, pediatrics, psychiatry, internal medicine) can be taken outside St. John’s in communities across NL and beyond to New Brunswick (NB), and Prince Edward Island (PEI), the Family Medicine clerkship in particular is designed to provide a predominantly rural learning experience.

Core clerkship in Rural Family Medicine: The Discipline of Family Medicine has established the practice of placing students exclusively in rural Family Medicine practices early on. Students work with and learn from rural physicians throughout NL, mainly in the ‘cottage hospital’ setting of small GP-run rural and remote hospitals. Students from NB, Prince Edward Island (PEI) and Yukon (YT) are matched to sites in their home province. The Family Medicine Clerkship has progressively been extended. The name of the clinical experience has been formally changed to ‘Rural Family Medicine’ to reflect the formal expectation that all students will spend a full 8 weeks living and working in a rural community and experiencing the full scope of family practice.

Electives and selectives: Family Medicine electives can occur in any setting. However, rural and remote electives have proven to be very popular with Memorial medical students. These sites give senior students more opportunities to practice advanced skills with greater independence under the supervision of rural Family Medicine teachers.

A 4-week mandatory rural selective provides the opportunity for students to learn in a rural setting in any core discipline, including Family Medicine. More recently, 12-week longitudinal rural rotations have given students the opportunity to experience Family Medicine and other specialties in a rural community. Students follow patients through the course of their illness, from clinic or the emergency room to the consultant appointment, hospitalization, surgery, and recovery. These opportunities teach continuity of care and a broad scope of practice.

Postgraduate vocational training

Postgraduate vocational Family Medicine Residency Training Program: The Family Medicine residency program trains residents in urban, rural and remote practice in sites across NL, NB and Nunavut (NU) over the course of 2 years. Each year, approximately 35 first-year residents enter the program while equal numbers graduate into practice.

The focus on rural training fits with the evidence that residents with at least 6 months of training are more likely to choose to practice rural Family Medicine24,25. In 2014, resident schedules were adjusted to reflect 2-year training opportunities by creating a regional ‘streams’ program in NL, which ensures a minimum of 6-months – and often up to 1.5 years – of postgraduate training in rural locations. The Northern Family Medicine (NORFAM) stream, established in 1992, allows residents to spend 21 months in Labrador26.

Moreover, the curriculum has changed to reflect the College of Family Physicians of Canada’s move to the Triple C Curriculum: continuity of education and patients; comprehensive Family Medicine; and training experiences that are centered in Family Medicine. The resultant longitudinal integrated experiences have enabled preceptors to work in greater depth with the residents to foster appropriate skill development while allowing residents the opportunity to become integral members of the communities in which they live and work. The Family Medicine residency training program also offers a 1-year enhanced skills program in Emergency Medicine and Care of Elderly, both of which allow residents to gain additional skills that add to their future rural practice.

After medical school

CME/PD: The Faculty of Medicine has recognized the importance of continuing medical education and professional development (CME/PD) for physicians to maintain their vital roles in rural communities. In addition to providing traditional CME to support practicing physicians, especially those in rural practice, Memorial has a very active faculty development program for rural preceptors anchored in an annual retreat. An example of these professional development programs offered by Memorial is ‘6 for 6’, which provides opportunities for rural physicians to enhance their leadership skills required to support rural health research and maintain their academic proficiency27,28. Additionally, the Discipline of Family Medicine provides extensive professional development for rural preceptors. Memorial also offers provincial library/information resources in partnership with the regional health authorities.

Learners & Locations

The Memorial L&L database used in this research is an administrative tool developed and used by Memorial’s medical school to collect data on student backgrounds, students’ learning locations, and Memorial MD-graduate practice locations and has been used since 2008. Administrative file data are extracted for all students from the time of admission and throughout their educational experiences. Entry-class sizes differed throughout our study period; there were 60 students per year in 2007–2008, 64 students per year in 2009–2012 and 80 students per year (60 NL students, 10 NB students, 4 PEI students and 6 other students) from 2013 to the present. Memorial’s medical school admitted only two international students during our study period because the school’s social accountability mandate focuses on meeting the needs of NL, Atlantic Canada, and Canada. In reporting the data, the largest class cohort possible was used for their location information. The purpose of the L&L database is to track medical students’ geographic trajectories from birth through high school and medical school placements to ongoing practice locations. The L&L database has allowed for the assessment of the ‘Pathways’ strategies employed by Memorial. The Health Research Ethics Authority (HREA) were consulted to determine if an ethics approval was required for this study. The HREA decided that no ethics approval was required since the interventions described were part of the medical school program and the administrative data used to assess each of them were defined as program evaluation or quality improvement. A privacy policy and compliance checklist were developed internally to ensure student information remained confidential and secure.

The following geographic categories were developed for the L&L database: rural community (<10 000 population); rural town (10 000–29 999 population); small city (30 000–99 999 population), mid-sized city (100 000–499 999 population), large city (500 000–999 999 population) and metropolis (over 1 000 000 population). This classification adapts the standard Canadian and international definitions of ‘rural’ to more closely reflect common functional differences in practice locations throughout NL. Smaller municipalities with >50% commuting flows to larger population centers are categorized in accordance with the larger center to reflect population access to larger center services, including medical care. In keeping with this categorization system, the current study used Statistics Canada 2011 population data to classify background, placement, and practice locations29.

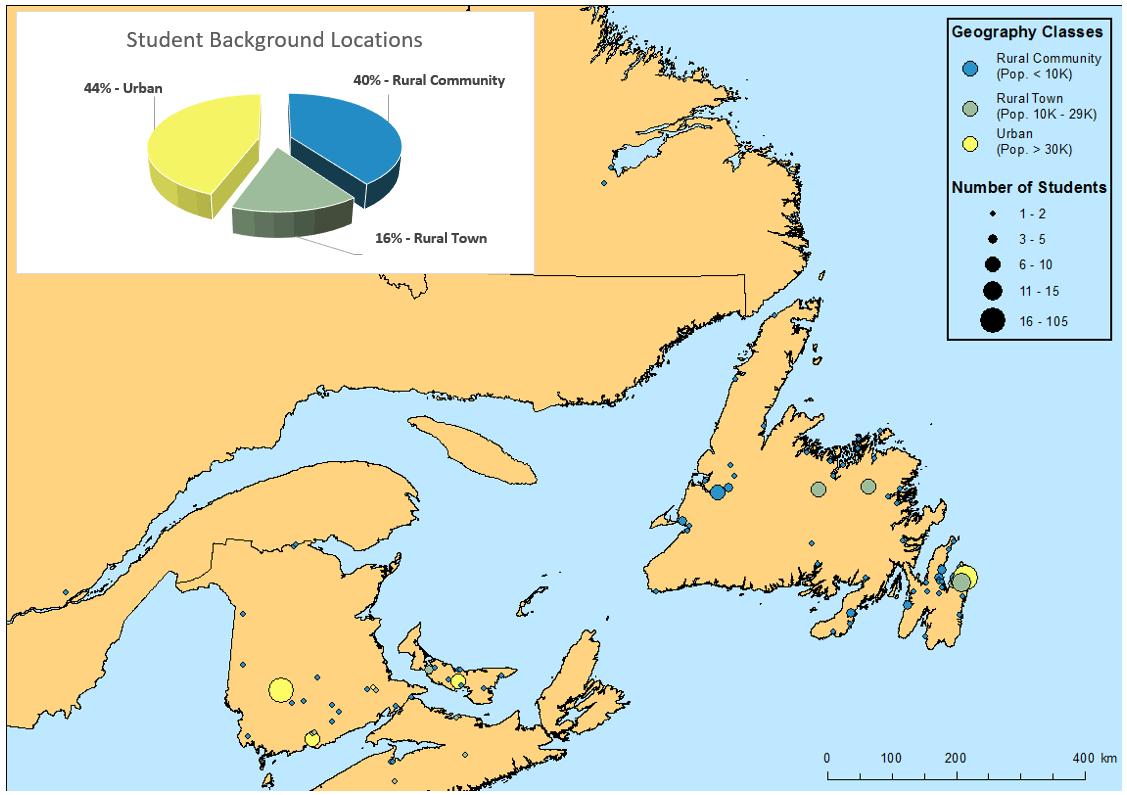

Using data reported from medical school applications, of the students from Memorial’s MD-graduating classes of 2011–2020 who had a confirmed address in Canada (N=698) and reported having a permanent address in Canada (N=651 students), 56% (40% rural community, 16% rural town) spent the majority of their lives before their 18th birthday in a rural location and 44% in an urban location (Fig1). Students who participated in the MedQuest program made up 19.3% (135 students) of the entire Memorial medical student body (N=698) for the same graduating classes (2011–2020).

As of September 2016, 23 Memorial MD-students self-identified as Aboriginal (15 currently active MD-students) and eight are now pursuing postgraduate studies – seven of whom are studying at Memorial (Family Medicine (n=4), Psychiatry (n=2) and Radiology (n=1)). Among Aboriginal students who provided address history (n=22), two (9%) were from an urban location, 20 (91%) were from a rural location (3 (14%) from rural towns, 17 (77%) from rural communities).

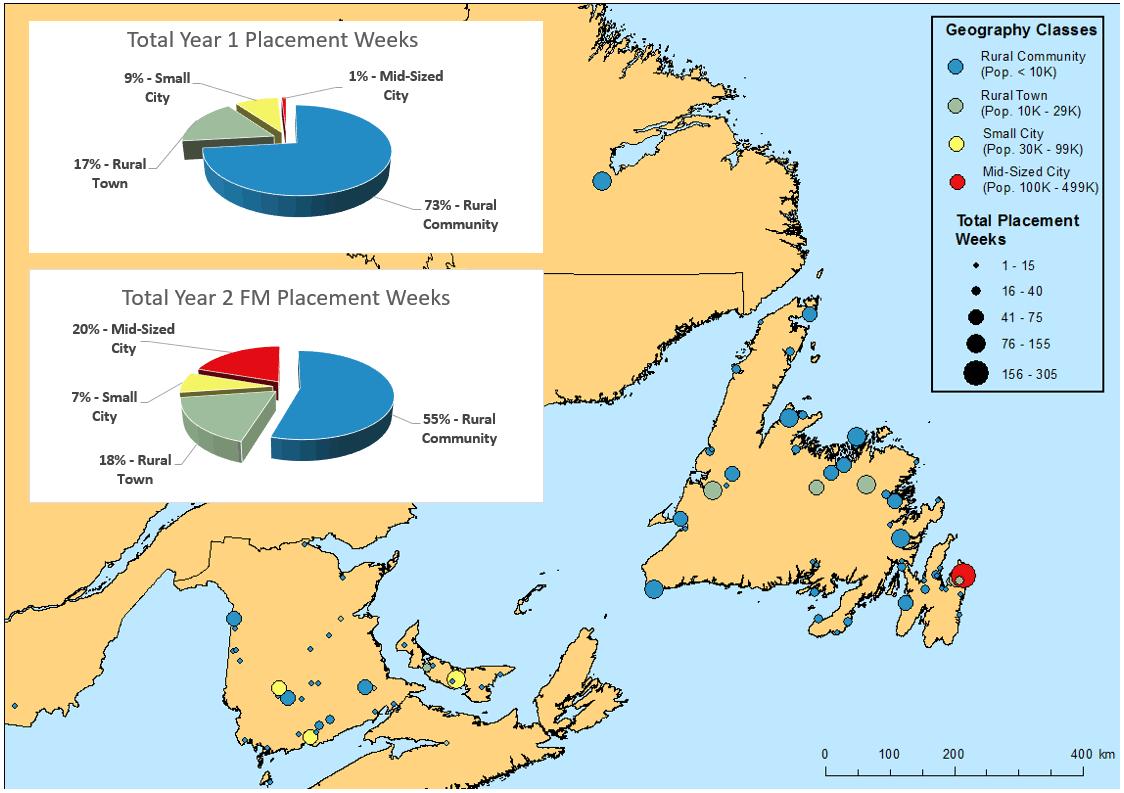

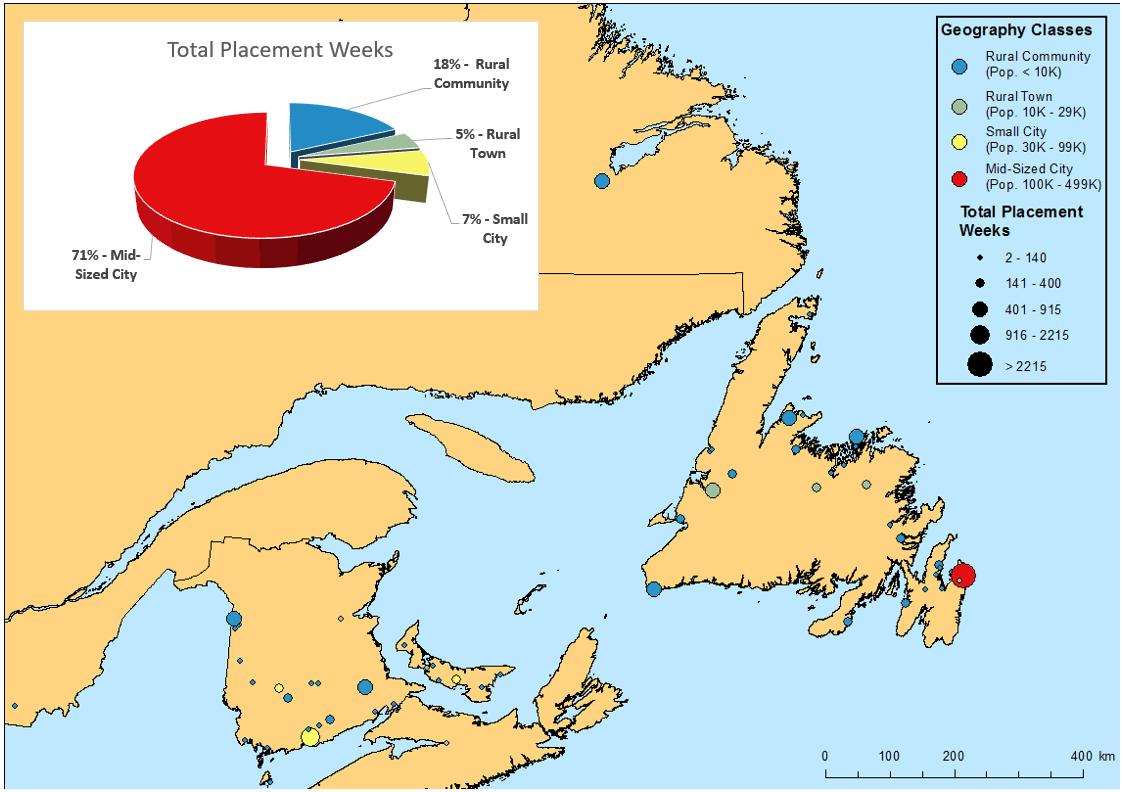

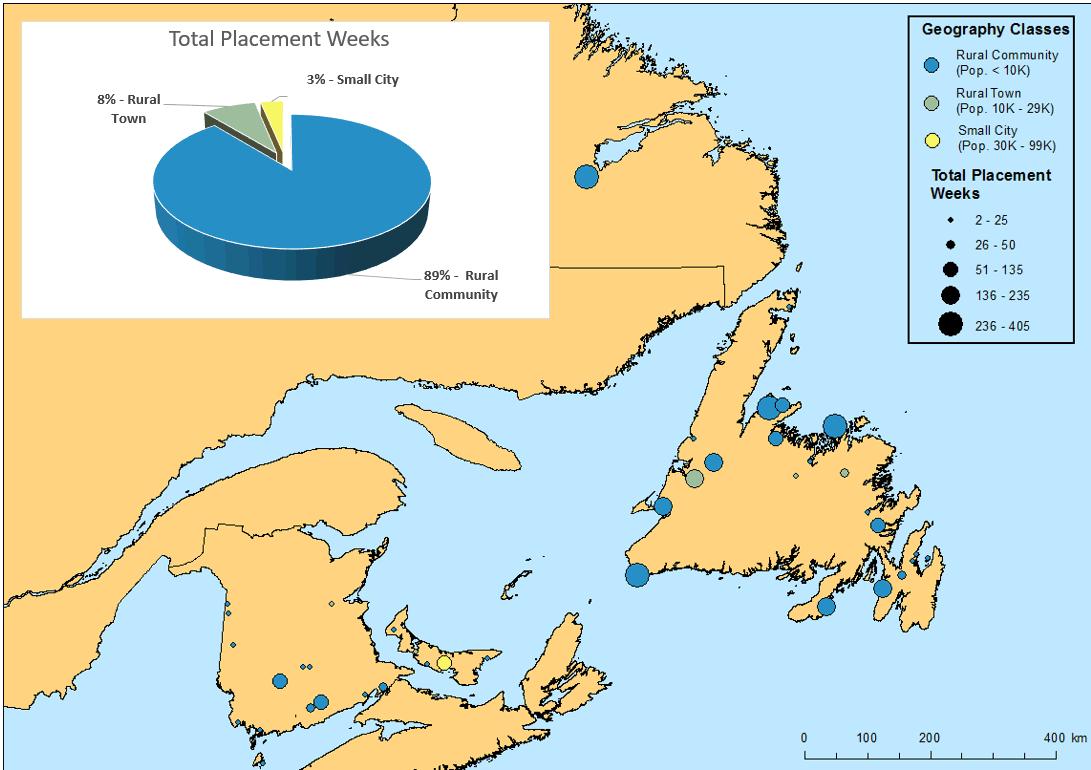

For Memorial’s MD-graduating classes of 2011–2019 (n=617 students), 90% of Year 1 Community Health placement weeks took place in rural towns and rural communities (Fig2). For Year 2 Family Medicine placements, 55% of placement weeks were spent in rural communities and 18% were spent in rural towns (Fig2). For Year 3 clerkships, MD-graduating classes 2011–2018 (n=537 students), 18% of placement weeks took place in rural communities and 5% took place in rural towns (Fig3). For Year 3 Family Medicine, MD-graduating classes 2011 to 2018 (n=537 students), 89% of placement weeks took place in rural communities and 8% took place in rural towns (Fig4).

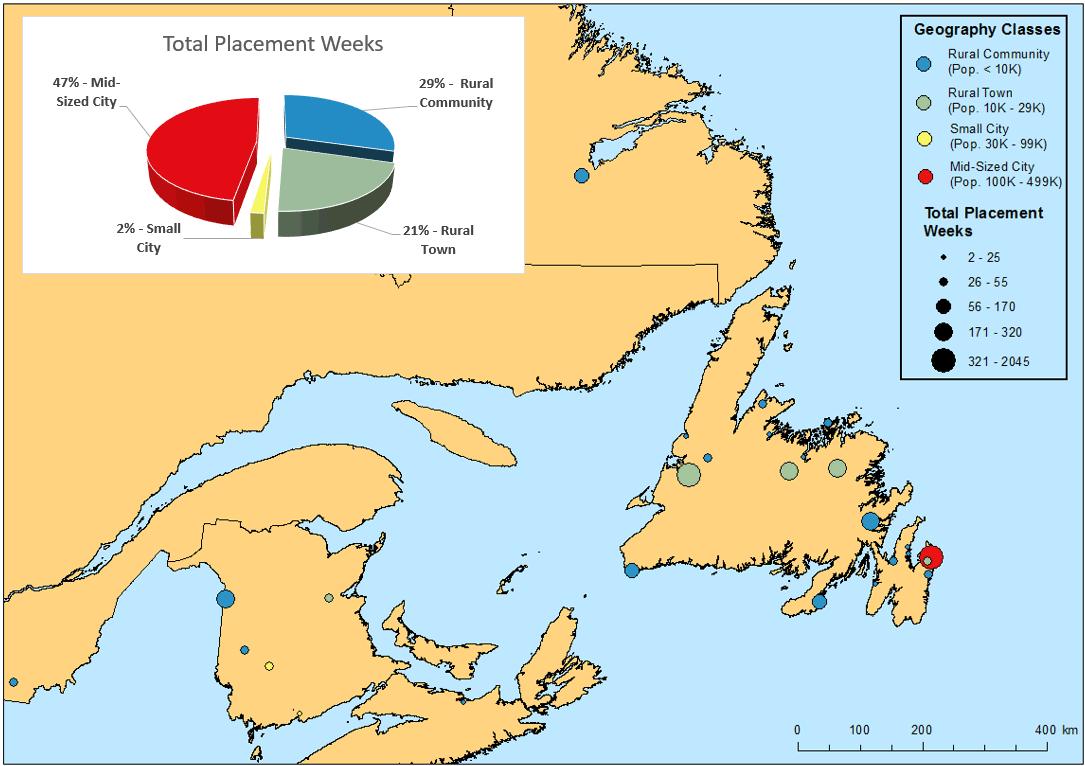

Of Memorial MD-graduates from 2011 to 2013 who completed Memorial Family Medicine vocational training residencies (n=49 residents), 100% completed rural training to varying degrees. For these 49 vocational training residents, the average amount of time spent in rural areas was 52 (55%) weeks out of a total average FM training time of 95 weeks. For Family Medicine residencies from July 2011 to October 2016, 29% of all placement weeks took place in rural communities and 21% of all placement weeks took place in rural towns (Fig5). For 2016–2017 first-year residents, 53% of the first year training is completed in rural location.

Figure 1: Map showing Memorial medical degree (MD)-student background locations for 2011–2020 graduating classes, showing locations where students spent the majority of their lives before their 18th birthday. Symbol size indicates total number of students. Only the Atlantic region is shown as it represents the majority of background locations.

Figure 1: Map showing Memorial medical degree (MD)-student background locations for 2011–2020 graduating classes, showing locations where students spent the majority of their lives before their 18th birthday. Symbol size indicates total number of students. Only the Atlantic region is shown as it represents the majority of background locations.

Figure 2: Map showing combined weeks per location for Year 1 Community Health and Humanities placements and Year 2 Family Medicine placements, Memorial medical degree (MD)-graduating classes 2011–2019. Symbol size indicates total number of placement weeks spent at each location. Only the Atlantic region is shown as it represents the majority of placements.

Figure 2: Map showing combined weeks per location for Year 1 Community Health and Humanities placements and Year 2 Family Medicine placements, Memorial medical degree (MD)-graduating classes 2011–2019. Symbol size indicates total number of placement weeks spent at each location. Only the Atlantic region is shown as it represents the majority of placements.

Figure 3. Map showing combined weeks per location for Year 3 All Clerkship placements, Memorial medical degree (MD)-graduating classes 2011–2018. Symbol size indicates total number of placement weeks spent at each location. Only the Atlantic region is shown as it represents the majority of placements.

Figure 3. Map showing combined weeks per location for Year 3 All Clerkship placements, Memorial medical degree (MD)-graduating classes 2011–2018. Symbol size indicates total number of placement weeks spent at each location. Only the Atlantic region is shown as it represents the majority of placements.

Figure 4. Map showing combined weeks per location for Year 3 Rural Family Medicine placements, Memorial medical degree (MD)-graduating classes 2011–2018. Symbol size indicates total number of placement weeks spent at each location. Only the Atlantic region is shown as it represents the majority of placements.

Figure 4. Map showing combined weeks per location for Year 3 Rural Family Medicine placements, Memorial medical degree (MD)-graduating classes 2011–2018. Symbol size indicates total number of placement weeks spent at each location. Only the Atlantic region is shown as it represents the majority of placements.

Figure 5. Map showing total Postgraduate Family Medicine residency program placement weeks spent in all location types, Memorial medical degree (MD)-graduating classes 2011–2013. Symbol size indicates total number of placement weeks spent at each location. Only the Atlantic region is shown as it represents the majority of placements.

Figure 5. Map showing total Postgraduate Family Medicine residency program placement weeks spent in all location types, Memorial medical degree (MD)-graduating classes 2011–2013. Symbol size indicates total number of placement weeks spent at each location. Only the Atlantic region is shown as it represents the majority of placements.

Lessons learned

Memorial, the only medical school in Newfoundland and Labrador is relied upon to provide a workforce for a significant rural and remote population, but who also need access to care provided by appropriately trained specialists in regional centers. As a result of this context, Memorial has had to develop functional pathways to rural generalist practice. The outcomes of Memorial’s medical graduates are presented in a companion paper, which provides a quantitative comparative analysis within the context of Canada and Canadian medical graduates1. Analysis of national data found that 26.9% of Memorial Family Medicine postgraduates were practicing in a rural location 2 years after completing their postgraduate training compared with the national average of 13.3% (2004–2013)29.

For NL’s context, an end-to-end approach has been important to Memorial’s overall success. Using a geospatial approach, this paper provides an in-depth look at Memorial’s rural generalist pathways to rural generalist practice. This starts with high school student engagement through the MedQuest program and other initiatives before a student is admitted and continues with rural-focused MD program and competency-based rural focused family medicine residency training program as illustrated by the information provided by the L&L database. The ‘Pathways’ approach can also be seen in Memorial, providing rural physicians with professional development and supports to become rural preceptors and/or full-time faculty members while still maintaining rural practice in their own communities.

Pathways to prepare medical students and residents for rural practice like those provided by Memorial require collaborative commitment by the government, the university’s medical school, practicing physicians, healthcare providers, patients, rural communities and their leaders. This paper shows that Memorial, for its part, is continuing to increase its rural focus content and learning as commitment to the needs of its province and country for rural physicians. In NL, Canada, and around the world, recruiting and retaining rural physicians remains a challenge requiring close collaboration with communities, physicians, health authorities, and governments. The shared goal in NL, as around the world, is accessible, effective, cost efficient health care as a World Health Organization priority for health for all the people living in the many rural and remote communities across the globe30-34.