Context

The belief that rural exposure during training can influence students to return to rural areas after graduation1-4, is one of a number of factors that influenced the Australian Commonwealth Government to establish the Rural Undergraduate Initiatives, including the University Departments of Rural Health (UDRH) Program. The University of Melbourne Department of Rural Health (UMDRH) was established at Shepparton, Victoria, in 1999, to teach and supervise undergraduate and postgraduate students, and to undertake research in rural settings.

To achieve its teaching objective, the UMDRH developed the Rural Health Module (RHM) in north-east Victoria. This subject immerses medical and other health professional students in rural, regional and Indigenous health services and communities, aiming to produce a transformative education experience5 and to influence their attitudes to rural practice and rural careers. All medical students participate in the 4 week RHM rotation in semesters 10 and 11 of the medical course; other health professional students elect to participate. The rationale was that senior medical students would have sufficient clinical skills to be able to apply them productively in the rural setting, thus enhancing their professional and experiential learning, as well as benefiting the rural health services and service providers with whom they interacted.

The RHM focuses on inter-professional and community-based experiential learning in regional, rural and indigenous communities. It aims to equip students with the knowledge and understanding for future participation in rural health, as well as providing an understanding of people of rural background. This article describes how the RHM was developed, implemented and formatively evaluated in its first 12 months.

Method and approach

The developers of the RHM adopted a participatory action research approach to the formative evaluation of the RHM. In addition, internal discussion papers, minutes of meetings and planning workshops, financial records and feedback from students, staff and preceptors were examined by the authors.

The development of the RHM as a generic inter-professional program was undertaken by the UMDRH staff, who were drawn from professions such as physiotherapy, nursing, dentistry, sociology, public health, pharmacy and medicine, in collaboration with the Faculty Education Unit, other schools and departments that place students in rural settings, and a wider group of stakeholders. A pilot program engaged health service managers, directors of nursing and GPs to organize placements for and supervise 160 fourth-year students in 25 rural hospitals in north-east Victoria and southern New South Wales6. The clinical preceptors were keen to be supported to engage students in their programs, health issues and communities. Two identified needs were: (i) assistance to find and fund student accommodation; and (ii) online support systems for tutorials and other interactions.

The pilot allowed an estimate of the formidable logistical and organisational issues inherent in an experiential course: accommodation, transport, catering and providing pastoral care for more than 250 medical students annually at regional and remote settings. Students were distributed across six rotations, each with approximately 50 students a year.

Developing the curriculum

The conceptual framework was developed iteratively, through inter-professional peer discussions, guided by the literature about rural health and rural living. A generic multidisciplinary and inter-professional framework for rural health education emerged, consisting of five key concepts that characterise the rural health context: rural-urban health differentials; access to services; confidentiality; cultural safety; and inter-professional teamwork7. This conceptual framework provided the scaffolding for the development of the RHM curriculum and guided the content of lectures, tutorials, community and clinical experiences. The curriculum was intended to build on content and clinical competencies taught in earlier semesters (1st-5th and 8th-9th), and to provide students with core and regional information about rural-urban differences to guide their experiential learning during the RHM. The 4 week RHM rotation is summarised (Fig 1).

Figure 1: The structure of the Rural Health Module (RHM).

The 2 day introduction covers key concepts, logistic and administrative information, rural road safety, and professional behaviour during clinical placements. Students are guided in how to use this framework to examine 'health practices' in their clinical placements. Members of the UMDRH staff are available for face-to-face support with students in Shepparton or support via phone or email for students not in Shepparton. Each pair of students is given a town or community information pack containing detailed information about the small town, its culture, its community hospital, and specific health information derived from the Victorian Burden of Diseases Study.

During their 2 weeks in the small towns, 3 key people supervise the students:

- The hospital preceptor, usually the nursing manager or hospital executive officer, who organises activities in a range of health services and provides day-to-day support.

- A GP preceptor from the community, where available and willing.

- The Community preceptor, who has a good knowledge of the small town, introduces students to community organizations and people. For example, a student with an interest in art might be introduced to a local artists group.

In their 3 days in Shepparton, students are placed with local community health agencies managed by the City of Greater Shepparton, Goulburn Valley Health, Goulburn Valley Community Health or Goulburn Valley Family Care. Students are co-supervised by UMDRH staff and nominated healthcare professionals in these agencies.

In their 3 days with Indigenous (Koori) communities, students are placed with Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organizations (ACCHO), which aim to address the deficiencies of mainstream health care institutions. ACCHO cover health, education, welfare, legal services, housing and employment and are part of a state and national network.

Assessment: Assessment includes a report from the community placement preceptor (25%), assessment of the student presentation (25%) and an end-of-semester written examination (50%)(Fig 1). Community placements grades ('fail-pass-exceptional') are weighted according to duration: small rural community (15%), Shepparton placement (5%) and Koori placement (5%). Student presentation marks are awarded for understanding of the key concepts, structure and level of analysis of the appraisal of a health practice, presentation skill, and engagement of other students in discussion. Examination questions are based on the common RHM learning experiences.

Logistics and preceptor networks in north-east Victoria

Along with training and support services (eg online support), a Preceptor Kit is made available. It contains:

- Administrative information (eg forms, incentives package, payments and indemnity arrangements).

- Academic information about the RHM structure and curriculum.

- Assessment and feedback forms for community preceptors.

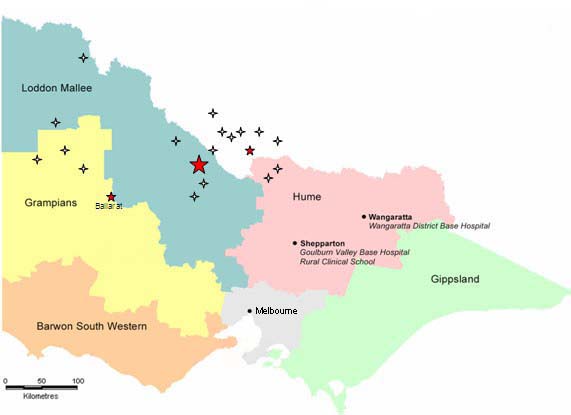

The three settings - Shepparton (a regional centre), Indigenous and small town - are located in north-eastern Victoria and neighbouring New South Wales (Fig 2). Apart from the distance of Shepparton from Melbourne (180 km), students have to travel from 50-300 km to get to the small towns in the region. This raises significant financial, logistic and safety issues.

Figure 2: Rural health module teaching sites in Victoria and New South Wales, Australia.

Accommodation

Student accommodation during the RHM is subsidised and include purpose-built student residences in the School of Rural Health, accommodation at community hospitals, hostels, motels, and billets. Accommodation is vetted by the local community mentors. No student accommodation is available in Aboriginal communities.

Evaluation framework

The RHM evaluation framework encompasses inputs, processes and outputs, enabling both formative and summative evaluation to determine if objectives are met with the resources available. Student input is sought on the content and delivery of the RHM, placement experience, and rural intentions. Long-term process and output indicators are being refined to measure the impact of the RHM on rural communities, health practice in rural environments and the quantity and quality of the rural workforce.

Issues

Students, staff and preceptors generally accept the value of the RHM in professional training. Students, however, expressed some concern about the compulsory nature of the subject. All stakeholders stressed the need for explicit learning objectives, relevant content and engaging delivery, resulting in a number of refinements to the delivery and format of the RHM. Also encouraged is innovation, for example using information and communication technologies (ICT) to provide pre-briefing information, to share experiences across cohorts of students and to facilitate online learning communities. Time and resources to support teaching remains an issue, particularly in the small and Indigenous communities.

Finding up to 1000 weeks of accommodation and clinical placements, distributed across rural Victoria (Fig 2), every year is an enormous undertaking for one university. Are these expectations realistic and sustainable? Are the expectations of the Australian Rural Undergraduate Initiatives Programs, of which the UDRH Program is one, realistic? If not, will the programs fail as 'placement fatigue' becomes more pronounced? The key sustainability issues are availability and costs of placements and appropriate accommodation; costs and safety of travel; and the capacity of community services and service providers to teach students.

Availability, affordability and capacity of teachers and services

The operating costs of the RHM are approximately AU$400 000 per year for 250 medical students. This includes building maintenance, transport, accommodation and rental subsidies, ICT support, student support services, office expenses and staff development and support. While there is academic and administrative support for the communities, they are only paid a token amount for taking students. Practice Incentive Payments for GP preceptors have improved to $200 a day but do not cover costs, estimated by the Rural Workforce Agency Victoria to be $240 a day. The cost of the supporting structure and staff is approximately $500,000 a year. This includes a half time academic coordinator, a full time administrative officer, and a range of academic and administrative support services provided.

The availability and affordability of appropriate accommodation, especially in the small communities are significant issues. The National Rural Health Alliance (NRHA) proposal that Commonwealth and State governments and health services, local governments and universities collaborate to establish and maintain student accommodation and educational facilities in small towns has had variable success. The expectations of and commitments to clinical placements by Commonwealth and State governments, rural communities and other non-clinician stakeholders must be matched by resources.

The morale and teaching skills of the preceptors must be developed and maintained; quarantined time to teach and to maintain teaching skills is essential. Private practitioners must be compensated for loss of income from teaching. These costs have not been factored into the equation for the RHM. So while the clinical placements may be available, the preceptors may not be. Even if they are available, could we afford them on the current scale and scope of the RHM?

Costs and safety of travel

The placements in small rural Victorian towns stretch over a distance of 400 km to the north west, 200 km to the east and south east, 100 km to the north and 100 km to the south, with virtually no public transport available. The UMDRH has purchased a number of vehicles to transport students to many of the small towns. However, these students then have no personal transport while at their placements. Most opt to use their own cars, which raises significant risks for students with little experience of country roads and conditions, as evidenced by the death of one of our international students in a traffic accident when returning from a rural placement.

Lessons Learned

The political and lobbying activities of the rural stakeholders to maintain the viability of rural health services has influenced The University of Melbourne, in partnership with many rural communities and health service providers in north and north east Victoria, to establish rural health experiences as a core activity in its medical curriculum. As a relatively brief rural exposure for senior medical students, the RHM emphasises a minimally directed, experiential and inter-professional program driven by five key concepts. Students are provided with logistical support and supervision from a network of trained preceptors.

However, issues of cost, appropriateness and sustainability remain. The effort of providing experiential rural placements for all medical students is significant and remains to be justified by long term outcomes, especially the quantity and quality of the rural workforce.

Quality placements, students and teachers can only exist if there is a quality health service, research, teaching and learning program. Herein lies a paradox: the necessary pre-conditions for the success of the program are simultaneously the intended outcome of the intervention that, at this point in time, are still not in place. In the current environment, education and research programs are mostly perceived an additional burden by health service providers.

In addition to adequate resources and an academic culture, a quality academic program requires rigorous continuing quality improvement procedures and processes. Rigorous and systematic quality assurance of all educational, research or service provision activities is essential to ensure that objectives are being met.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Commonwealth and Victorian Governments and Professor Richard Larkins for their support; Faculty Education Unit: Sue Elliott and Agnes Dodds; Members of the RHM team: Vicki Atkinson, Chris Chapman, Sally Belcher, Andrew Crowden, Dawn DeWitt, Tanya Garling, Bridget Hsu-Hage, Donna Jackson, Louise Jackson, Carmel Johnson, Munir Khan, Vishnu Sharma, Collette Sheridan, David Simmons and Jean Wood.

References

1. Brooks R, Walsh M, Mardon R et al. The roles of nature and nurture in recruitment and retention of primary care physicians in rural areas: a review of the literature. Academic Medicine 2002; 77: 790-798.

2. Laven G, Beilby J, Wilkinson D, McElroy H. Factors associated with rural practice among Australian-trained general practitioners. Medical Journal of Australia 2003; 179: 75-79.

3. Simmons D, Bolitho L, Phelps G et al. Dispelling the myths about rural consultant physician practice: the Victorian Physicians Survey. Medical Journal of Australia 2002; 176: 477-481.

4. Wilkinson D, Laven G, Pratt N, Beilby J. Impact of undergraduate and postgraduate rural training, and medical school entry criteria on rural practice among Australian general practitioners: national study of 2414 GPs. Medical Education 2003; 37: 809-814.

5. Taylor EW. Building upon the theoretical debate: A critical review of the empirical studies of Mezirow's transformative learning theory. Adult Education Quarterly, Washington 1997; 48(1): 34-50.

6. Wood J. Rural Health Week Interim Report. Shepparton, Australia: Department of Rural Health, University of Melbourne; 2001.

7. Bourke L, Sheridan C, Russell U, Jones G, DeWitt D, Liaw ST. Developing a conceptual understanding of rural health practice. Australian Journal of Rural Health 2004; 5: 181-186.