Introduction

Cancer incidence and mortality have increased in recent years among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (from here on respectfully referred to as Indigenous). While Indigenous people are as likely as non-Indigenous people to be diagnosed with cancer, they are 1.3 times more likely to die from cancer1. Five-year survival is significantly less for Indigenous people than non-Indigenous people1. Indigenous people are more likely to be diagnosed with more fatal cancers, especially liver, lung and cervical cancers1. These differences can be explained in part by lower participation in screening2, delayed diagnosis and receiving less cancer treatment3. In addition, a number of systemic barriers, such as discrimination, transport, accommodation, finances and limited access to culturally appropriate services, serve as challenges to treatment and prognosis4,5. It is also known that some Indigenous people hold strong beliefs about the causes and preferred treatments for cancer, which can influence health behaviours of those with cancer and their support networks6. This is important because greater perceived support received by cancer patients has been shown to improve quality of life and reduce depression, and be beneficial for overall health7,8.

Previous investigations of the causes of health disparity among Indigenous Australians have identified the need for culturally responsive approaches to healthcare provision and the importance of partnership with community for sustained and meaningful engagement9. Prior to undertaking this project, the research team were working with a remote community in the state of Queensland, Australia, investigating patterns of care within the primary healthcare setting for Indigenous people with cancer. In the course of this study, an Aboriginal Elder in this community requested the team explore community perceptions of cancer. In response to this request, and in consultation with community members, the research team proposed two main aims, which were to make community perceptions of cancer visible in the community and to develop resources for the community to represent these perceptions.

Methods

Conceptual framework

This project was informed by community-based participatory research (CBPR) processes10. CBPR is considered an appropriate research method to improve health equity by connecting research evidence and practice through community engagement and social action10. CBPR processes facilitate a partnership between researchers and community and are more likely to respond to local context. Reciprocal interest and ownership of learning and social change are enhanced when CBPR processes are used and as such promote sustainable engagement and action10,11. Following the initial request for this project, the research team organised community engagement forums to ascertain the need for a project to explore community perceptions of cancer. Group discussions helped to identify perceptions and define resources to represent these perceptions.

Study participants and recruitment

This project was conducted in a small regional community in Queensland. The community has a population of 967, of which nearly 85% identify as Indigenous. Approximately 57% of the population are aged over 20 years (18.4% aged 20–29 years; 10.9% aged 30–39 years; 11.5% aged 40–49 years; 10.5% aged 50–59 years and 6% aged 60–69 years). The main industries of employment are local government administration (19.8%), hospital (11.3%) and education (primary 10.7% and secondary 7.3%)12. The community is serviced by a state government funded multipurpose health clinic providing emergency care, and inpatient, outpatient and residential aged care. There are a number of visiting specialists and allied health services to the clinic. The community is approximately 175 km from a large regional hospital service. Prevention and early intervention programs for ear health, sexual health, drug and alcohol interventions, antenatal and postnatal care are also available13.

Representatives of two organisations (one community and one international non-government organisation) as well as the cultural adviser who instigated the project were engaged and agreed to be community champions for the project. The community champion role was particularly important in terms of gaining local support for the project and sustaining project momentum. Staff from the two organisations assisted to raise awareness of the project among their respective networks. Recruitment strategies included the placement of flyers in visible areas of community, and promotion through the local radio station (ie interviews with the research team). Participation was open to consenting community member aged 18 years and over, who were present at the first community forum when the study was presented and discussed. The following day, a second community forum was held and participants would self-select for the activity using the Photovoice method and yarning groups. Participants were encouraged to get involved in both activities. Prior to conducting forums and group sessions, the project and implications for involvement were reviewed and written consent was obtained.

Data collection and analysis

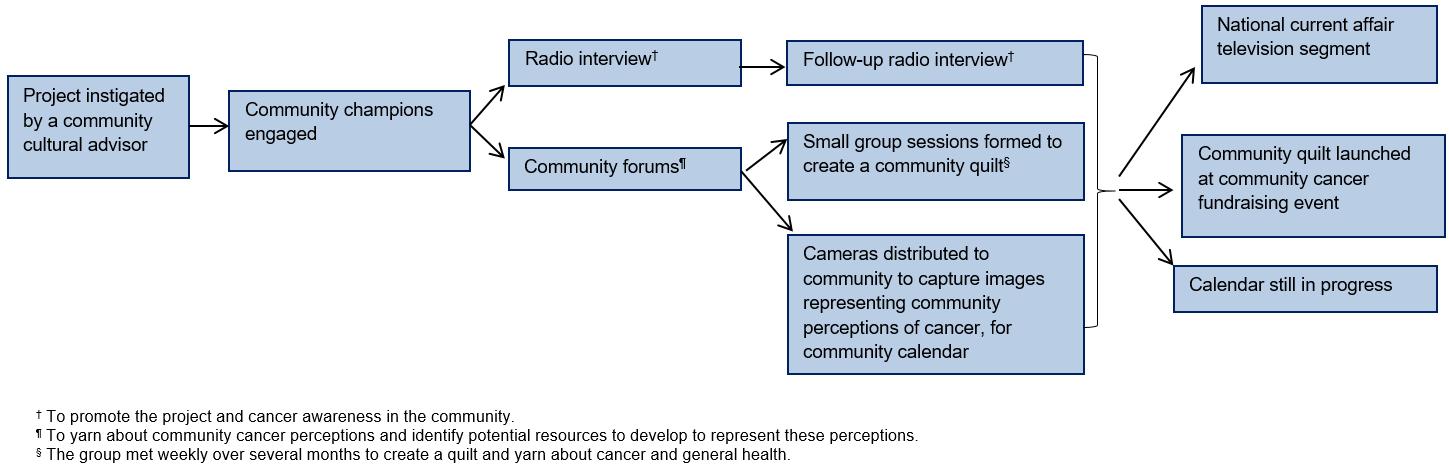

Participatory, qualitative and visual research methods were employed to gather data. Figure 1 is a schematic overview of the project. Qualitative data to explore and define cancer in the community were collected from yarning groups including both men and women at two open community forums held at the beginning of the project, and subsequent yarning groups with women at sessions to create a resource. A yarning group was also held at a cancer fundraising day to seek perspectives about involvement in the project. Yarning is the way Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people refer to storytelling14. Yarning methods are considered a culturally appropriate research method, emphasising relaxed conversational processes, that seek to build a relationship with the participants to co-create knowledge and share experiences in a particular area of interest15. There is an interaction (two-way process) between researcher and participants14. Yarning methodology consists of different types of yarning: social, research topic, collaborative and therapeutic yarning15. In this study, yarning research topic methods were used to explore the perceptions of cancer in the community, and this was done in a purposeful yet informal manner. Written informed consent was obtained from eligible participants prior to audio-taping the yarning groups. Data were also included from publicly available interviews about the project broadcast on radio and television16. Data were transcribed verbatim and analysed thematically17. Three research team members (JM, CB, BA) met at intervals throughout the project to identify prominent themes related to cancer perceptions in the community and at cessation of the project to identify main themes related to community assessment of the project.

Photovoice using cameras was the visual method chosen to capture images and stories representing community cancer beliefs. Photovoice is a research strategy using photography to represent individual or community perspectives of a topic or experience in a context specific way18. It is a culturally appropriate method as it promotes ownership over knowledge, addresses power imbalances between the researcher and participants, and builds capacity of participants and researchers19,20. The purpose of Photovoice was to supplement qualitative data and to potentially use the images in resources selected by the community. Following the initial community forum, those participants who expressed interest in the Photovoice activity were provided with small, fully automatic and digital cameras and shown how to use them. Participants who had their own devices (mobile phones or cameras) were encouraged to use them. Fully automatic cameras were chosen to reduce the training required to use them and to limit potential bias through researcher involvement. Those who took photos met with the research team to share their photos, why they chose those images and what they represent on a subsequent visit to the community. Themes arising from this process were identified and clarified within the group18.

A consensus decision making approach was used to select resources and activities to represent community perceptions of cancer and raise cancer awareness. This approach acknowledges the needs of individuals and community and gives voice to all participants as part of the process21,22. Two activities were chosen: creating a community quilt and producing a community calendar.

Figure 1: Schematic overview of project procedures.

Figure 1: Schematic overview of project procedures.

Ethics approval

Prior to conducting this project ethics approval was obtained by the QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute Human Research Ethics Committee (reference number P2237).

Results

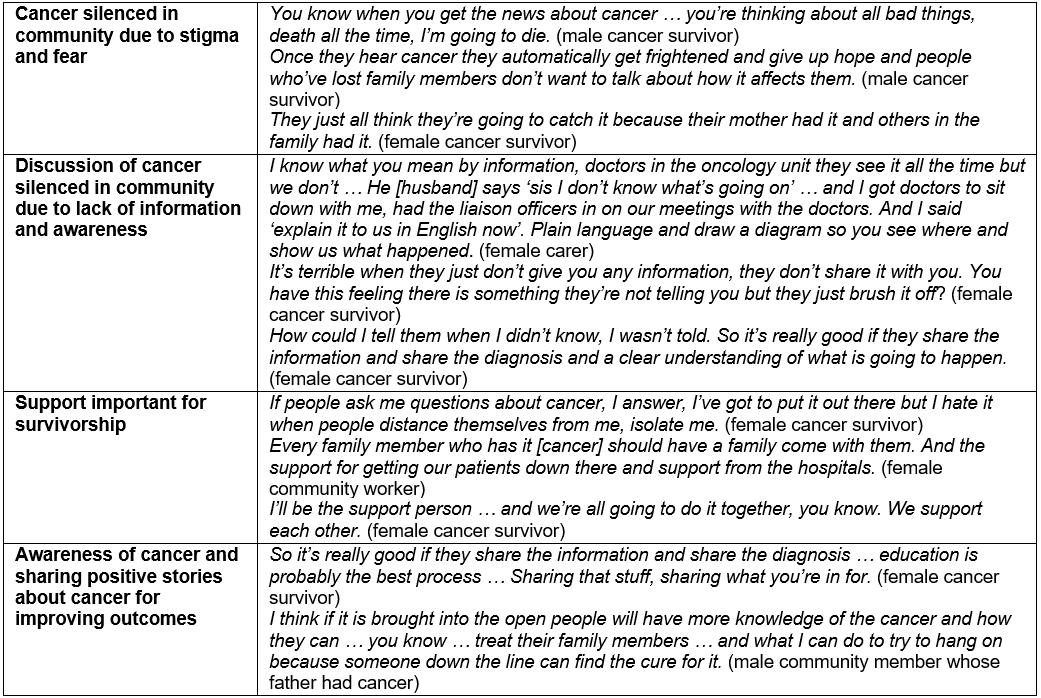

Analysis of data collected in this project highlights the perceptions of cancer in a remote Queensland community. Findings are summarised and illustrative quotes are presented in Table 1. Approximately 50 men and women aged 18 years or more attended the community forums, some being cancer survivors or carers for someone with cancer and others from the broader community. Significant verbal input was received from about 20 people at the forum yarning groups. A core group of around 11 women attended subsequent women’s groups.

Table 1: Quotes illustrating perceptions of cancer in the community

Cancer perceptions in the community

Three main themes were derived from thematic analysis of data collected about community perceptions of cancer identified by participants as important to improving cancer outcomes: (1) silence in the community, (2) support important for survivorship and (3) awareness of cancer and the importance of sharing positive stories.

Discussion about cancer in this community has been mostly silenced. Many people, including health professionals, do not talk openly about cancer. Reasons for this include stigma, cancer being seen as dirty, and fear. Cancer was generally feared, as little was known about it, and thought to be associated with death because a number of people needed to leave the community for diagnosis and treatment, some of whom died while away. Easy to understand information in the community, at primary health services or at tertiary health services during treatment, was considered scarce, complex and not relevant to community needs. Although cancer wasn’t seen as common in the community, most people could identify a close friend or family who had been diagnosed with cancer. For those who had lost a family member to cancer, the impact on the broader family and community was described as significant.

Support from family and broader community was recognised as important for facilitating both emotional and practical support. Several cancer survivors shared how they felt isolated and rejected by those in the community as a result of a cancer diagnosis. Concerns about understanding and navigating the health system during cancer treatment were shared by several survivors and family members of cancer patients, particularly given they were travelling long distances from a remote community to a large urban hospital. Some participants described their fear of losing close networks as so intense that they chose not share their diagnosis with family and/or friends.

Sharing their cancer story as a way of raising awareness and contributing to reduced stigma and fear was considered very important to survivors. While considered by participants as critical for improving cancer outcomes, the group recognised that community awareness of cancer prevention, signs, symptoms and the importance of screening was not high. A particular challenge noted by the women was the challenge of passing on messages about cancer prevention and screening to the younger generation. The group noted concerns about young people being less aware of traditional ways of living, teaching and learning and therefore may be less receptive to stories and advice from Elders.

Resources to raise cancer awareness

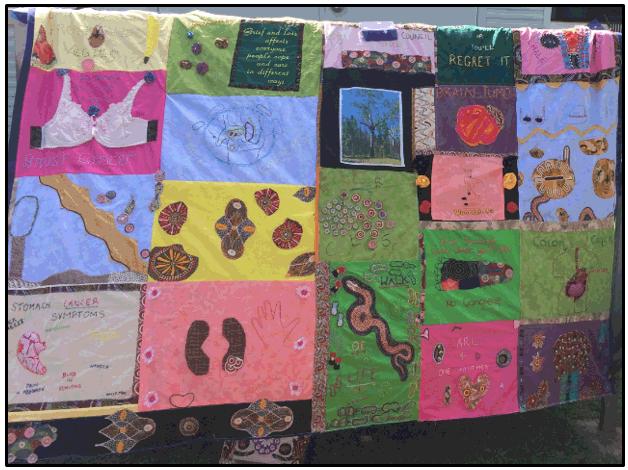

Resources chosen for development by the community to represent cancer perceptions and raise awareness were a community quilt (Fig2) and community calendar.

A number of women including some cancer survivors formed a group who met at the community women’s shelter. The women chose to make a community quilt with squares showing messages or stories about cancer. Initially women thought that the quilt could be used by cancer patients while in hospital. After further discussions about how to better utilise the quilt to spread messages about cancer, the group decided to hang the quilt in the local primary health clinic. The quilt represented community perceptions about cancer as well as important messages about cancer prevention and the disease itself, thereby acting as a message medium. Project team and local health workers were included in quilt making sessions and yarns at the shelter. Many conversations within the group throughout the process of creating the quilt related to cancer. Other conversations related to general health and wellbeing as well as stories about life in the community and reciprocal sharing of recollections. This was important for building a level of trust, sharing and support as well as engaging in yarns about health behaviours, signs and symptoms of cancer, cancer screening, cancer prevention, diagnosis and treatment. The finished quilt was unveiled at the community cancer fundraising day.

The second resource chosen was a community calendar. A number of photos representing cancer in the community were taken for use in developing a community calendar and messages about cancer awareness, screening and prevention for each month chosen. While several images have been contributed and progress has been made, completion of this resource was not possible in the project timeframe. It is hoped that the images and messages will extend the reach of cancer awareness activities to the broader community as well as contribute to reducing fear and stigma about cancer.

Figure 2: The community quilt, with each square representing community cancer perceptions.

Figure 2: The community quilt, with each square representing community cancer perceptions.

Outcomes and community feedback

An important outcome of the project was interest from a nationally recognised news and current affairs journalist who featured the project as well as interviews with community members on a segment about Indigenous cancer16. This segment generated great interest in the project and increased conversation, contributing to increased awareness of cancer in the community as well as being a positive story about community action.

Participants, primary healthcare professionals and community champions viewed the overall project as valuable for facilitating and improving the conversation about cancer with family and friends, the broader community and among health professionals:

All that hype around that program got people talking and we’ve [the women’s group] been talking straight up about it. (female community worker)

That’s a good outcome. She took her work [the quilt square] home and showed her husband and they talked about it. (female community member)

Participants also saw the group sessions as important for providing a shared and safe space for support, for asking health related questions and as an instigator to share knowledge and stories:

You learn together, it was a wonderful project. I laughed a lot. (female health worker)

This project has been a healing process for people … because I don’t know how many people deal with the grief from cancer. (female community worker)

I’m hoping that by having this [the quilt] up it’ll start conversations about cancer for our mob and people start thinking about living healthy and eating healthy and going and getting things checked. (female community worker)

The positive responses to the project in the community could indicate improved cancer awareness amongst the broader community, which could go some way to improved screening and help-seeking behaviour.

Discussion

The current project illustrates cancer perceptions of a remote Indigenous community in Australia and how these perceptions were represented in a community identified resource to raise cancer awareness. Cancer is not spoken about in the community due to stigma and fear. Participants also identified a lack of information about cancer from health services and a lack of community awareness about cancer as other reasons why cancer is silenced. Participants recognise that support from family and community along with local cancer survivors sharing positive cancer stories would be important steps for improving cancer outcomes.

It has been argued that stigma is an important cause of a number of health disparities23. Cancer patients who engaged in risky behaviours considered to have caused their cancer have reported greater negative stigma than those considered not having engaged in behaviours that may have caused their cancer24. Stigma can significantly affect screening, health seeking behaviour and provision of support25-28. Consequently actions to address stigma are important and research has an important role here through raising awareness, dissemination of evidence based information and community education29. This project contributed to combatting stigma by starting the community conversation around cancer, raising awareness and providing health related information and education at community forums and women’s group sessions. In addition, project exposure on the local radio station and on the national television segment provided an opportunity for conversation about cancer as well as a space for cancer survivors to share their stories. There is some evidence to suggest that cancer awareness activities at a community level may improve awareness and increase the likelihood of earlier presentation, diagnosis and treatment30-32. However, awareness activities should be accompanied by systematic action to strengthen the health system, improve social determinants to health, reduce inequities and reduce exposure to risk factors30-32.

Community participation in the research process shows promise in reducing disparities in health outcomes. Implementing community based participatory processes is more likely to lead to the development of culturally appropriate methods, context specific interventions, reciprocal and respectful relationships and sustainable change33-35. Employing community participation processes has led to improvements in knowledge and stigma about HIV/AIDS in Thailand36, cervical screening among Vietnamese-American women37 and a reduction in breast cancer disparities between African American and white women38. Community participation in the present project was embedded throughout the project from identifying the problem through to evaluating the project and presentation of the project at a conference.

This project was set in a remote Queensland community and sustained presence of the research team in the community was a challenge; to counter this, a number of community champions were identified. The benefit to the project was threefold. First, the community champion continued project momentum whilst the research team were not present in the community. Second, the support and engagement of the community champion facilitated rapport and trust with community members and overall support for the project. Third, participation as a community champion in the project built community capacity by developing a range of project skills, communication skills and health related knowledge. Identifying and building relationships with community champions is an important way to build project support and sustainable reciprocal relationships, particularly when working with the community’s considerable distance from the research team39,40.

Primary health care is an important setting for action to reduce health disparities, engage in community level awareness raising and prevention activities and provide culturally appropriate care for Indigenous people41,42. It plays an essential role in promoting healthy behaviour, improving cancer screening and diagnosis, and plays an increasing role in cancer follow-up care43. However, it is critical to deeply engage community in program and service development, particularly in rural and remote communities33-35. This project evidences the important role of primary health care in working alongside other health and community services to address community identified concerns, in this case instigating conversation around cancer. However, it is critical that the community be deeply engaged in program and service development, specifically in rural and remote communities.

Strengths and challenges

An important strength of the project is engagement of community champions to contribute to project inception and implementation as it improves the likelihood of sustaining the project over the longer term. Community defined and driven projects enhance the prospect of success due to a sense of ownership and empowerment over the project, and this project was well supported by the local primary health clinic and other important community organisations.

Challenges were faced with the use of cameras for Photovoice. Only a small number of images have been received to date, such that most qualitative data was collected from yarning groups at community forum and group quilting sessions. Furthermore, a self-selected sample was used, and therefore potential bias may have arisen whereby participants who volunteered for the activities may have a different perception of cancer than those who didn’t participate. In particular, men were challenging to engage in the project over the long term and participation fluctuated (eg Photovoice or sewing a quilt may not have attracted male participants). Furthermore, women’s business was conducted separately while men did not formally and purposefully met for social and yarning purposes during the research period. However, significant verbal input was provided by around 20 community members at the two initial forums and by 11 women at subsequent group sessions. In addition, women involved in the project reported having conversations with male relatives about cancer screening and symptoms as a consequence of their participation in the project; the lower involvement from men may have implications for ongoing help-seeking behaviours.

Conclusion

Silence around cancer in this community may influence awareness and discussion about cancer, screening participation and help-seeking behaviour. In this project, engaging with the community created a safe space for conversation around a previously taboo topic, which could potentially lead to improved screening and help-seeking behaviour. The role of primary health care, particularly in rural and remote areas, in reducing health disparities by partnering with community to conduct awareness and prevention activities and by providing culturally appropriate care for Indigenous people is emphasised. This could contribute to improved screening, earlier diagnosis and support for Indigenous people throughout the cancer trajectory.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Indigenous community who participated in this project. The authors gratefully acknowledge and thank the regional community who participated in this project. They also acknowledge the project team of the National Health and Medical Research Council (#1044433).

This study was undertaken under the auspices of the Centre of Research Excellence in Discovering Indigenous Strategies to improve Cancer Outcomes Via Engagement, Research Translation and Training (DISCOVER-TT CRE, funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council #1041111), and the Strategic Research Partnership to improve Cancer control for Indigenous Australians (STREP Ca-CIndA, funded through Cancer Council NSW (SRP 13-01) with supplementary funding from Cancer Council WA). The authors also acknowledge the ongoing support of the Lowitja Institute, Australia’s National Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding agencies.