Introduction

Australia is rich in culture, history and natural resources, with a unique landscape, geography and climate1,2. With over 24 million inhabitants, it is the world’s sixth largest nation in terms of land mass3. Nearly one-third of the inhabitants live in areas outside major cities, with 2.3% of the population living in ‘remote or very remote areas’1,3,4. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare defines ‘rural’ as anywhere that has an ‘urban centre’ with 999 999 inhabitants or less, and ‘remote’ as anywhere having an ‘urban centre’ with 4999 inhabitants or less5. The factors of population dispersion that make this country unique can pose significant challenges. In research examining rural Australia, a number of common themes have emerged including low population numbers and density, geographic isolation and a limited diversity of labour1,2,6-9. With so many people living in rural areas, this presents a special set of challenges for health clinicians providing emergency care, and it means they have a set of support needs very different to that of their urban counterparts1,10,11.

Australia has an ageing population with an ageing rural workforce1-3,12-14. Our life expectancy as a nation is on the rise, reflecting better overall health3. Based on population projections by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, by 2064 there will be an estimated 9.6 million people aged 65 years or more, and 1.9 million aged 85 years or more, constituting 23% and 5% of Australia’s population respectively3. This is also reflected in the age of the workforce, with over 50% of the nurses and midwives registered to practice with the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) this year aged over 50 years15. Chronic disease rather than injury, accident or infection is now the biggest killer in this age range3. Health outcomes are poorer for Indigenous Australians, people living outside major cities, those in low socioeconomic areas and people with mental illness16. This is reflected in their higher rates of illness, health risk factors and death compared to other Australians, which presents further challenges for rural nurses because the majority of the people who have poorer health outcomes live outside of metropolitan areas1,5,12,16.

Of the many different groups of people living and working in rural areas, health clinicians make up the largest workforce, with nurses forming a significant percentage of this heterogeneous group1,2,7,12,16. There is a widely recognised global shortage of healthcare professionals willing to work in these rural areas, which threatens the health of these communities as they struggle to access adequate health care and other resources1,2,14,16-18. Working in these areas presents significant challenges11,14,15,17-20. Common themes identified in the literature range from difficulties with geographic isolation1,2,4,6-9,14; problems with recruitment and retention1,8,16,18-22; and a lack of access to continuing education, due to difficulty getting time off from work; limited financial resources2,6,8,9,11,14,15; and a perceived shortage of applicable topics1,2,6,8-10,18,23-26. The overwhelming majority of nurses working in rural emergency departments are middle-aged women working part time in areas characterised by their presentation diversity and unpredictability2,14-16,20.

Caring for the critically ill does not occur solely in large urban hospitals. Nurses practising in rural settings practise as ‘nurse generalists’, caring for a wide range of patients, including those needing critical care2,6,9-11,15,16,19,23. Generalists need a wide variety of skill sets, and it can be challenging for clinicians in rural areas to maintain current practice through continuing education2,9,11,16. Rural nurses are multi-skilled and have an expanded role compared to their urban counterparts11. Health status of people has a major impact on their community. If there are not enough experienced clinicians able to provide excellent emergency care in these rural areas then the healthcare needs of the community will not be met2,11,16,18.

This scoping review seeks to determine the support needs of nurses providing emergency care in rural settings as reported in the literature. The main focal point will be on Australian research, with international work included where relevant. With nearly one-third of Australia’s population living in rural areas, Australian nurses providing emergency care in rural areas face challenges unique to themselves and have support needs different to their urban counterparts1,3,4,10,11. The review will focus on four main areas of need, as established in the literature. Recommendations will be developed based on analysis of themes identified in the literature.

Methods

A scoping review method was selected because it provides a sound preliminary assessment of the available research literature, enabling knowledge gaps to be identified26. It aims to identify the size, scope, extent and nature of the research evidence, and identifies a broad range of literature27,28. This enables policymakers, planners and leaders to decide whether a full systematic review is required29.

Search strategy

The Joanna Briggs Institute guidelines for scoping reviews were used. These recommends the comprehensive search of at least two online databases with an analysis of the text words in the title and abstract. This is followed by a secondary search using all key words; the reference lists are then checked for additional studies26. In commencing the review, a search was performed using the key words ‘rural’, ‘nurse’, ‘emergency’, ‘clinicians’, ‘support needs’, ‘challenges’ and ‘Australia’. The PubMed, Cochrane and ERIC e-databases were searched, and a Google Scholar search was also completed to widen the subject knowledge. The search was further broadened to include all work that adhered to the above criteria either through exploring the citations given in the literature reference lists or other articles listed in Australian rural health publications27.

Inclusion criteria

Because of the changing face of rural health, and the amount of information available internationally, only research from the past 5 years focusing on Australian peer-reviewed research with some grey literature was used; international research that was relevant to the Australian context was also included. Broad eligibility criteria were used to capture the full extent of literature in this field. All sources of evidence were searched including primary studies and text/opinion articles, leading to greater sensitivity in the search results, as is desirable in scoping reviews27.

Results

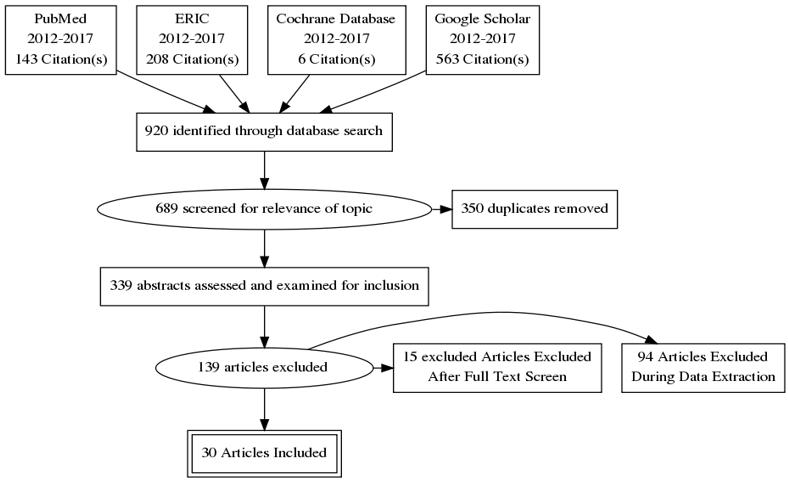

The initial search through all databases produced over 900 articles. Duplicates were removed, and the remainder was further assessed for relevance based on their title and abstract, resulting in 30 articles being selected (Fig1). An article was included if:

- it was in English

- it focused on clinicians in rural and remote areas

- it focused on reported support needs or challenges in rural and remote health

- it focused on clinicians providing emergency care

- the research was either peer-reviewed or grey literature27.

The main areas of concern revealed in the literature fell were a lack of effective graduate training programs or the availability of mentors2,8,18,19,24,28,30, poor recruitment and retention numbers1,8,17,20-22, a need for better recognition for the extended role of the rural and remote clinician1,2,10,31 and poor access to role-specific ongoing education2,6,8-10,15,18,22,23. These were compounded by feelings of geographic isolation1,2,6-8,14,18,22,23 and perceived poor funding2,6,8,9,18,21. These issues will be further explored in four broad areas:

- unpredictable nature of rural emergency care and the need for further education and support

- extended role of the rural emergency nurse

- implementation of rural nursing graduate programs

- issues surrounding the recruitment and retention of rural nurses.

Figure 1: Flowchart of review search strategy.

Figure 1: Flowchart of review search strategy.

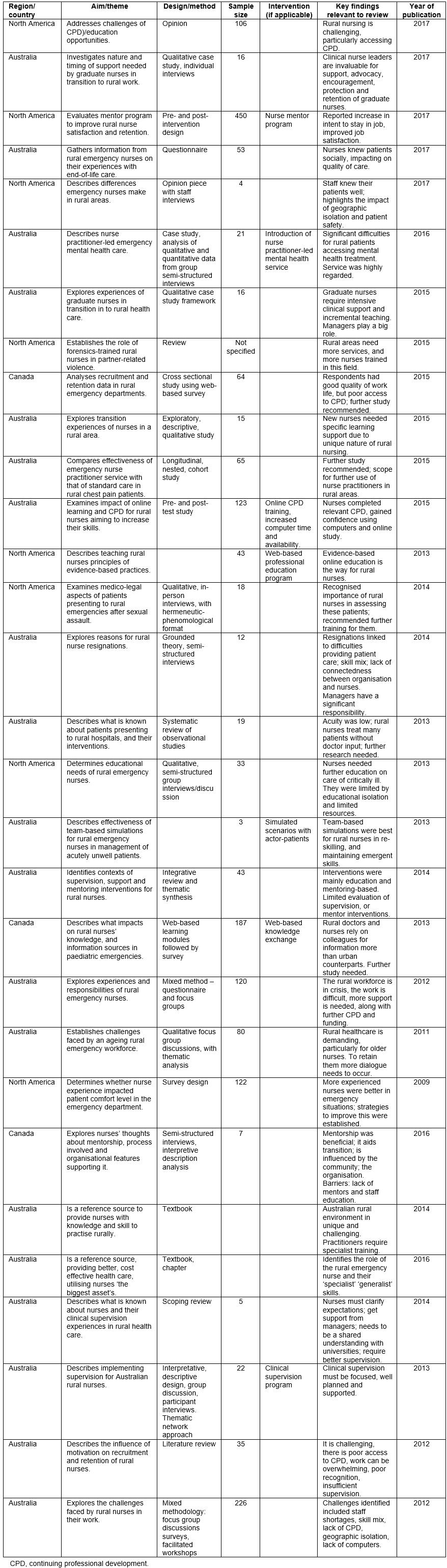

Table 1: Summary of literature on support needs of clinicians providing emergency care in rural areas

Unpredictable nature of rural emergency care and need for further education and support

Emergency nurses working in rural areas must be prepared to deal with a variety of presentations, such as labouring pregnant women, people with mental health disorders, chest pain and trauma, including paediatric emergencies1,2,6,9-12,18,19,22,32. One of the most common themes identified in the literature was issues relating to the unpredictable nature of the work, and nurses’ concerns and lack of confidence when dealing with acutely unwell patients2,10,14,15,20. Nurses feel that they rarely have the chance to partake in educational programs, particularly those designed for the whole emergency team to practise working together in life-threatening situations8,10,11,18.

The difficulty in accessing continuing education is influenced by several factors: some rural hospitals lack funding2,6-8,14,18,21, so it is challenging for nurses to secure time off to attend courses; few staff are available to backfill their position; and there is a shortage of ‘casual’ staff to fill short-term absences1-3,8,14,18,20-22,24,30,33,34. Limited financial resources make the geographical isolation harder to overcome, because the cost of travel in rural settings is high, it can be time consuming, and accommodation and course fees can be prohibitive1,2,8. Due to advances in technology, emergency nurses working in rural areas have more options for continuing education than ever before, which is crucial for maintaining a skilled workforce in rural health care facilities9.

Many nurses perceived a lack of relevant continuing education topics2,6,8-10,14,18,22,23; they reportedly favoured further education in an ‘active participation’ style with group-based scenario simulations2. Observers found that registered nurses in rural settings in particular found this type of education beneficial to their ‘re-skilling’ or maintaining their emergency management skills10. In one study, it was discovered that rural emergency clinicians (including both doctors and nurses) were actually less likely to make use of online training guidelines and education compared to their metropolitan-based colleagues, and were more likely to consult their work colleagues for advice when requiring further knowledge on a subject23. Much of the literature also identified a need not just for improved emergency skills but also for a better basic knowledge of key areas such as assessing and managing presentations relating to mental health issues, caring for bariatric patients and geriatric patients, and for victims of domestic violence and sexual assault; and managing paediatric presentations2,9,23,32,35,36.

Extended role of the rural emergency nurse

Rural nurses felt they required better recognition and respect for their extended ‘specialist’ role, because they work in rural areas, often on their own with minimal support or backup, functioning with a severe lack of resources, including both staff and equipment2,11,14,37. They have increased autonomy and responsibility compared to their urban counterparts2,10,11,25,38 and felt that this was not sufficiently reflected in their remuneration2. Professional independence and an extended scope of practice can also mean professional isolation14,39. Sometimes, the rural emergency nurse is the only clinician who might see a patient in an emergency situation, acting as an administration officer, nurse, radiographer, ‘wards person’, care assistant, social worker and physiotherapist or any other associated healthcare role2,11,18,22. In many rural hospitals, there is no doctor on site full time – the nurse is responsible for assessing whether the doctor must be contacted and required to attend, leading to increased pressure on the nurse to ‘make the right decision’, a challenge not experienced in metropolitan facilities2,11,31. In some areas the use of nurse practitioners has already been successfully implemented to improve the care of patients presenting with chest pain or mental health problems, or because of domestic violence and sexual assault1,9,32,35,36,38, just as emergency nurse practitioners are now increasingly prevalent in urban emergency departments.

Implementation of rural graduate programs

Research found that rural graduate nurses benefited from graduate programs with an emphasis on the effectiveness of adequate mentorship and ongoing clinical supervision2,8,18,19,24,26,28,30. Graduate nurses are just commencing their clinical careers, face greater challenges in delivery of safe patient care and require more support than their more experienced rural colleagues23. Evidence indicates that workload, skill mix and organisational pressures are still of concern for new graduates, and heavily influence their ability to safely and effectively perform their role26.

Research shows that opportunities such as access to appropriate and adequate training; active involvement of stakeholders in program design, implementation and evaluation; a needs analysis prior to intervention; marketing; organisational commitment; adequate clinical supervision; and regular program feedback and evaluation could all contribute to making graduate mentorship programs just as effective as training initiatives when it comes to retention8,16,19,26. The effectiveness of the mentorship programs depends on the timely support of graduates working in rural emergency departments. It is adversely influenced by inadequate staff allocation and resources, and a limited number of clinical supervisors, which are compounded by deficits in supervisors’ ‘mentorship’ knowledge and education8,18,24,26,28. New graduates need intense clinical support but many experienced emergency colleagues do not know how to meet these support needs24,26. To perform well as rural emergency nurses, graduates need to have advanced problem-solving skills, and be able to multi-task, be independent and ‘step up’ and assume the team leader role early on in their career28. Rural nurse leaders have an essential role in supporting new graduate nurses, and in facilitating the successful retention of nurse graduates in the nursing workforce21,24,34. New graduates rely on them as clinical leaders to provide support, encouragement, feedback, emotional backing, advocacy, openness and protection from the unique demands or rural emergency nursing34.

Issues related to recruitment and retention of rural nurses

Research demonstrates the importance of sufficient recruitment and retention strategies for any workforce. It is consistently demonstrated that this is a key support need for rural nurses1,8,16,19-22. In Australia, to attract new nurses to rural areas, the traditional approaches include financial incentives, training opportunities; and attractive relocation packages including work visas, accommodation, ongoing clinical support, and the opportunity for personal growth16,39. This has resulted in many overseas-trained nurses (and doctors) applying for positions; however, few choose to stay in their area of practice after their contract is completed, resulting in a high turnover of staff and a transient population14,16,21,30. Outcomes can include a significant variation in standards of knowledge and skill sets, because many do not have postgraduate qualifications or rural specific training. There is evidence to suggest that these incentives being offered to nurses is creating a growing workforce of rural nurses inexperienced in rural health14,21.

Most strategies to improve recruitment and retention have been predominantly education and training based or involved the use of graduate programs or mentorship pathways, which have shown some success in recruiting and retaining rural nurses18,19,24,28,30,34. Studies in the past 5 years appear to favour this approach for graduate nurses taking their first steps in to their new careers and for more experienced workers taking on the new challenge of providing rural emergency care. However, when nurses felt that they were unable to provide what they thought was appropriate patient care, the result was poor retention16,21. In these incidences, it is up to the clinical nurse leaders to ensure that the core values and realities of the department align with the perceptions and expectations of the staff21.

Barriers to recruitment and retention identified in the literature include rural emergency departments finding it difficult to attract, support and retain adequately skilled workers15,19. Efforts are hampered by several factors, such as high clinical workloads (especially for lone practitioners); limited career pathways; difficulties accessing appropriate professional development opportunities; a lack of formal mentoring programs; and little or no allotted time for professional study, or clinical supervision8,17,19,20. Clearly documented positive approaches that were beneficial to recruitment and retention were improved education, and better training, supervision and mentorship. What is not clear however is what effect these interventions have on staff, service and patient outcomes8,20,21.

Discussion

The literature reviewed offers a significant foundation from which to understand the support needs of emergency care nurses in rural Australia. It is important, however, to recognise the limitations of the current research and the significant gaps in the existing knowledge. According to Kidd et al in 20142, and Baker and Dawson in 201331, little is known about the needs of the clinicians in rural emergency departments, therefore to ensure that the training and education for this group is maintained there needs to be further research on the subject2,31.

Plenty of research for places such as North America and the United Kingdom is available but these places do not necessarily have the same geographic distribution as Australia. Many of the Australian studies have been performed on relatively small sample sizes, with some groups consisting of only handful of participants. The geographic distribution of the studies is also important; what applies in far north Queensland may be different to rural New South Wales or Victoria. The government for each state manages health resources, and each has a different approach, budget and initiatives1. Given current knowledge is limited, and that Australia is such a complex, diverse nation, further study is recommended to influence future government policy.

The literature says that, unlike their urban counterparts, rural nurses are not exposed to high acuity emergency presentations as a core part of their daily workload, leading to significant concerns about perceived ‘skills rusting’2,6,14. Consequently, rural nurses may not feel as comfortable with advanced skills such as primary assessment, and the treatment, stabilisation and transfer of a critically ill patient6,9. As a rural ‘specialist’ there is a need to maintain competency of a wide variety of skills, which creates challenges for nurses trying to maintain their current practice through continuing education across many areas2,6,8-11,14,18,19,23. There is evidence to suggest that rural emergency nurses would prefer more job-specific training in the form of in-the-field group training by visiting educators2,10. The implications for further education are that the development and effective delivery of continuing education to rural nurses is required, because meeting these workers’ unique educational needs is vital to safe patient care and nurse confidence9,11.

Improved computer-based evidence-based training for rural nurses can help with educational deficits; however, few appear to take advantage of the available online training options6,14,23,25. One possible explanation for this is that clinicians require better access to computers to complete the teaching; another opinion is that hospital bosses may overestimate their staff’s computer proficiency7,14. There may be available online training, but not all clinicians are confident or competent when using computers and online training resources, therefore employers should ensure their staff have access to continuing professional development programs that improve their information technology knowledge. This has the potential to improve staff productivity, healthcare standards and patient outcomes7,14.

Consideration should also be given to the training and use of clinicians in extended roles, enabling them to meet the increasingly complex needs of the local populations1,11,32,38. Greater numbers of emergency nurse practitioners could be employed; urban areas have already employed more nurse practitioners to suit the needs of their local populations15,38. The advancement of the nursing scope of practice has the potential to improve access to emergency health care for rural patients; it also acts as a recruitment and retention strategy to entice nurses in to the workforce who may be looking for a new challenge, or wishing to work more autonomously1,8,18,40. In some areas, the use of nurse practitioners has already been successfully implemented to improve the care of patients presenting with a diverse range of problems1,9,32,35,36,38. Rural services are also under increasing pressure due to the ageing population; if health services are to be expected to be able to meet this future demand then more research and investment are required2,12. Despite the increasing prevalence of emergency nurse practitioners and nurse practitioners, relatively little is known about the safety and quality of the service in the rural emergency department environment and further research is necessary38.

The geographical distribution of nurses is also interesting. As of March this year, 1125 nurses registered with AHPRA were endorsed to dispense medication as a rural nurse practitioner15. Of these nurses, over 800 were registered in the state of Queensland alone, which is a large disparity in advanced role cover for the country. It requires study, investment and understanding of the influencing factors. There has been little uptake or research on the subject of the role of emergency nurse practitioners and nurse practitioners; in general, the short trials that have occurred were promising, but in all cases recommendations were made for further funding and study32,35,36,38. Absent from the literature was investigation into disparities in the geographic distribution of rural nurse practitioners; a better understanding of this could assist the expansion of the role.

It is well understood that effective recruitment and retention of rural nurses improves staffing numbers, which has been shown to improve patient care8,17,21. The inability to provide adequate patient care has been identified in the literature as a major cause for resignation amongst rural nurses16,21. This has significant implications for influencing policy, because the shortage of emergency nurses willing to work in rural hospitals is worsening. These hospitals often have a lower retention rate than urban areas, which is concerning because high staff turnover rates often lead to poorer patient outcomes16,19,21. Researchers found that there were plenty of training opportunities available for rural emergency nurses, but that access is limited by multiple constraints2,20. An example of the initiatives in place is a program run by the Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine, which has developed a mentoring program to give junior doctors an opportunity to be ‘nurtured and inspired’ by their senior colleagues. Initiatives such as this could so easily be geared towards improving the numbers of emergency nurses in the same areas41. Most state and territory health services run initiatives looking to recruit ‘regional and remote’ nurses. Recruitment campaigns by the state government in Queensland acknowledge the prospect of professional isolation, offering ‘incentives and benefits’ to improve recruitment15,38. However, some industry experts think that more training pathways should be available, with improved promotion of these programs to convince more nurses to ‘go rural’40. One suggestion is the addition of more structured graduate programs with better marketing, and the encouragement of urban universities to increase their acceptance of students from country areas, because this is an important determinant of future place of practice16,40. This could significantly improve the number of graduate nurses entering the workforce with a commitment to rural emergency care. The non-profit organisation Rural Health Workforce Australia recommends the implementation of a rural graduate program that is offered to allied health workers, similar to those used by nurses and doctors, thus improving the multidisciplinary team approach to rural care40.

Graduate mentorship programs exist but their studies either concentrate on one small community or use a small group of participants, so it is hard to assess whether they are statistically relevant. Results so far look encouraging and warrant further study to ensure they are evidence-based and performing as intended. The effectiveness of these approaches, particularly for graduate nurses commencing work in rural emergency departments, has featured increasingly in the literature, but relatively little is known about them8,18,24,28. Significantly, successful completion of the graduate nursing mentor program has been shown to improve job satisfaction amongst nurses and augmented their desire to stay within the role24,28,30,34. There is plenty of international literature to support the use of these programs but, although similarities can be seen, further information is required from rural areas of Australia18,30. A well-designed program should feature both mentorship and direct clinical support for new graduate nurses and ‘new starters’ to emergency departments26. This ensures that new staff feel well supported and have adequate access to learning opportunities whilst feeling that they are a respected and valued team member. This promotes a sense of ‘connectedness’, so that they do not feel disillusioned with their role, and are more likely to stay21,30. This is important, because it has become increasingly evident that poor retention is not always a result of geographic or social isolation, or lack of financial incentives; it can be a combination of poor support and a misalignment between nurses’ expectations and reality16,21,30.

When creating a mentor program for clinicians new to rural emergency work, a needs analysis must be performed prior to an intervention. Organisational commitment, particularly from the clinical leaders (and clinical facilitators where available) is imperative, to promote a healthy culture and vision for the emergency department8,21,26. Further Australia-based studies would be worthwhile, preferably over several areas and involving a mixed methodology, focusing on the role and benefits of direct clinical support, the effectiveness of one-on-one mentorship and ongoing relevant continuing professional development opportunities.

Interestingly, most research to date lacks any mention of the social side of rural life, and whether this has any impact on nurses’ decisions to stay or leave their roles. Invariably in small communities, most nurses and their patients know each other socially, and they often have to care professionally for friends and relatives33,37. The psychosocial impact of a nurse’s role in a close-knit rural community requires further investigation, because it is a potentially significant support need. The limitations of this review are that it only included studies from the past 5 years, and included research only on rural nurses, and not other professional disciplines, meaning that the knowledge is not necessarily transferable to other healthcare roles.

Conclusion

Nurses providing emergency care in rural areas face a range of challenges. The most common support needs identified by nurses providing emergency care in rural areas were a perceived lack of effective graduate training programs or the availability of mentors, limited access to role-specific ongoing education, poor recruitment and retention numbers, a need for better recognition for the extended role of the rural emergency nurse, and poor access to role-specific ongoing education. These were compounded by geographic isolationand poor funding. To enable safe and effective patient care, staff in rural and remote environments need access to appropriate, focused and evidence-based education, which can improve nurse satisfaction and retention, as well as an improvement in available graduate programs featuring adequate direct clinical supervision. Further research across all areas is strongly recommended, particularly regarding the psychosocial impact of providing rural emergency care, because this is virtually unreported in the literature and could inform recruitment policy.