Introduction

Diarrheal disease, a major cause of death across the world, is associated with inadequate sanitation, lack of access to potable water for consumption and absence of hygienic behavior such as hand-washing to reduce the transmission of disease1,2. WHO has estimated that, globally, approximately 1.7 billion cases of childhood diarrhea occur annually3. Also, close to 600 000 children die each year from diarrheal disease, the majority in low- and middle-income countries4. This is remarkable because the problem can be easily prevented with clean water, availability of latrines and good hygiene practices5-7. Even though access to sanitation, the practice of good hygiene, and safe water supply could save many children every year, 768 million people around the world must rely on unimproved water sources8-10. Additionally, one in three people (2.4 billion) live without sanitation facilities – including 946 million people who defecate in the open6. Evidence has linked poor sanitation with growth stunting, environmental enteropathy and impaired cognitive development – long-term disorders that aggravate poverty and slow economic development11.

Poor status of water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) can impact the growth and development of children in multiple ways12 and school-aged children are more at risk than any other age group of suffering from diarrheal illnesses that could be prevented by clean water and good hygiene13-15. Investigators of systematic reviews reported that inadequate WASH in schools results in adverse health outcomes including infectious, gastrointestinal, neurocognitive and psychological illnesses16. Infectious diarrhea alone results in about 0.7 million deaths in children aged under 5 years in 2011 and 250 million lost school days17. Furthermore, it has been estimated that infections contracted by children in schools will lead to infections in up to half of their household members10.

Interventions to implement WASH programs in schools aim to improve the health and learning performance of school-aged children, and the health of their family members, by reducing the occurrence of diseases associated with poor access to safe water and good sanitation2,18. Recent literature has demonstrated the impact of school WASH interventions on diarrhea-related outcomes among school-going children16,19,20. A meta-analysis showed reductions in diarrhea associated with the promotion of hand-washing and improvements in water quality and the disposal of excreta of 48%, 17% and 36%, respectively7. Another review found that various WASH interventions reduce diarrhea risk between 27% and 53% in children2. School WASH interventions have also been associated with improvements in educational outcomes and reductions in absence caused by illness19,21. In addition, WASH initiatives may facilitate the achievement of UN Sustainable Development goals by 2030, particularly Goal 6, Target 6.2 (‘Achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all, and end open defecation’)22.

In Ethiopia, access to safe drinking water and sanitation services are among the lowest in sub-Saharan Africa, and water- and sanitation-related diarrheal disease is among the top three causes of all deaths23. In addition, many Ethiopian schools have inadequate sanitation. Where sanitation facilities exist, they may be poorly designed and constructed or may not have sufficient water for hand-washing; only 1% of rural schools in Ethiopia have on-premises water sources, adequate sanitation and water and soap for hand-washing24. According to the national WASH inventory, of an estimated 27 000 primary schools across Ethiopia, 7% meet the official standard for students per hand-washing stand, 21% meet the official standard for students per latrine, 31% have a safe water supply and 33% have sanitation coverage25. Although efforts to improve WASH in primary schools are being undertaken, studies conducted in Ethiopia have found a drastic diarrhea problem26-28, and high levels of parasitic infections and soil-transmitted helminth morbidity among school-aged children28-31. Despite this, none of the previously conducted studies ever assessed the prevalence of diarrhea in schools, and there is no reliable evidence of a difference in diarrhea prevalence among children attending Ethiopian schools that implement WASH interventions and those that do not. Furthermore, there is no indication whether the implementation of WASH interventions has affected the prevalence of diarrheal diseases among school-aged children in the study area of Habru district, north-eastern Ethiopia. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to compare the prevalence and associated factors of diarrheal diseases in school-aged children between those schools in the study area that adopted WASH interventions and those that did not. The findings from this study may help school directors, rural health policymakers and health managers in the development and implementation of WASH programs in schools and other communities in Ethiopia.

Methods

Study area and period

The study was conducted in the rural Habru District of Wollo Zone, in the north-eastern part of Ethiopia, about 490 km from Addis Ababa (the capital city of Ethiopia). According to an annual report of the Habru District Health and Education offices, the district has 97 schools (35 are primary schools) attended by 39 962 children. Of the 35 primary schools, 10 have had school WASH programs for more than 2 years and the rest have not implemented any WASH program. Of the total number of children, 5358 are in grades 5 and 6.

Study design

A school-based comparative cross-sectional study design was used to compare the prevalence of diarrheal diseases in children attending schools that had implemented WASH programs and schools that had not in Habru District from January to March of 2016.

Study population and sample detail

All students aged 8–15 years from 35 primary schools of the Habru District (10 WASH-implementing and 25 non-WASH-implementing schools) were the source population of the study. Randomly selected students in selected primary schools were the study population.

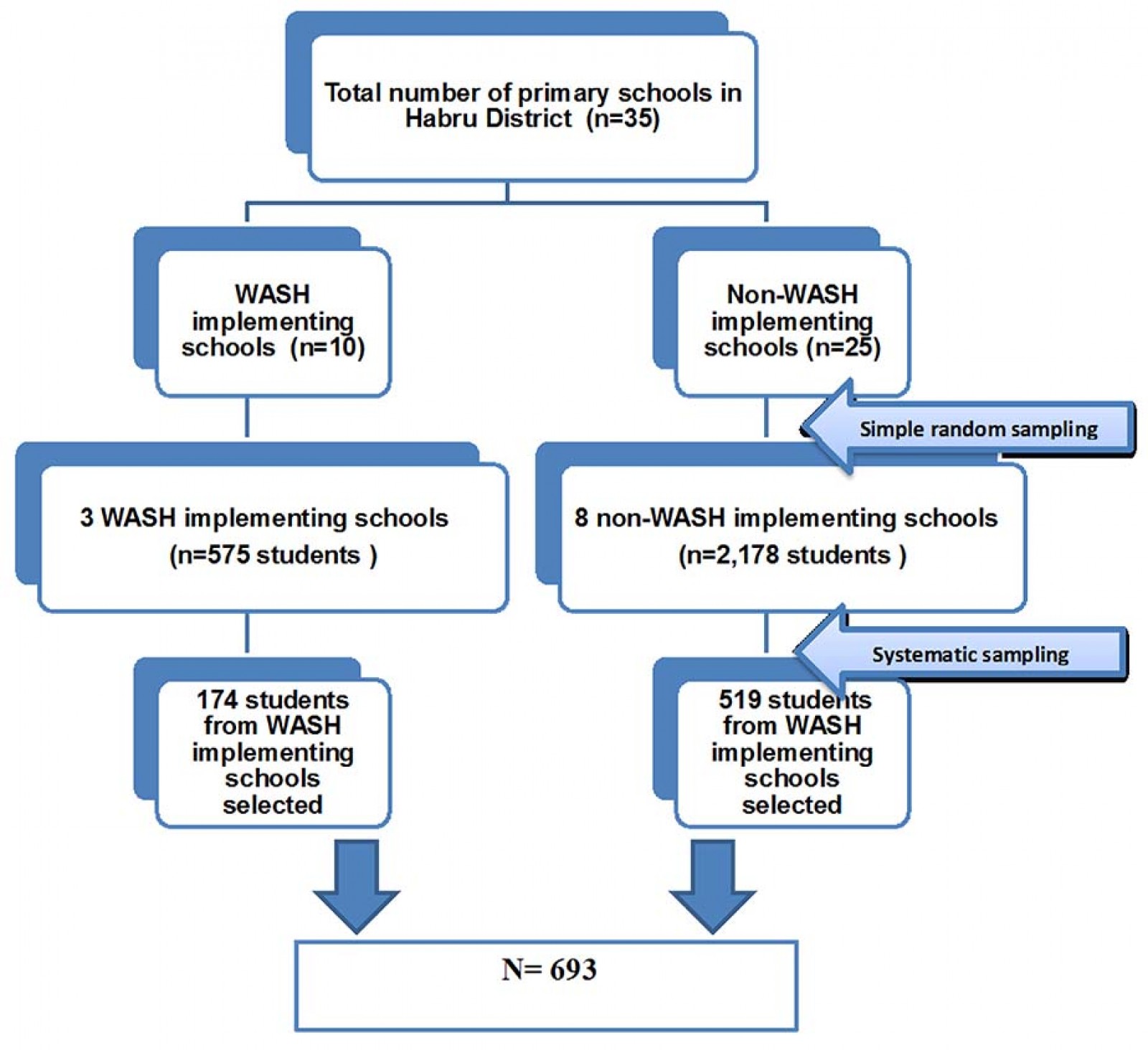

Eleven primary schools were randomly selected for the study from 35 Habru District primary schools – three of these schools were implementing WASH interventions. Students aged 8–15 years were randomly selected from these 11 primary schools. Students attending night school or who had not been attending a WASH-implementing or non-WASH-implementing school for at least 2 years were then excluded from the study (Fig1).

The required sample size to provide a robust measure of the prevalence of diarrhea was calculated using Epi-Info v7 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; http://www.cdc.gov/epiinfo) by estimating as an outcome variable 50% prevalence of diarrhea within the previous 2 weeks among children in schools that had not implemented WASH programs (because there were no previous studies indicating the prevalence of a diarrheal disease among school children in these schools). The sample size calculation used a 95% confidence interval (CI), 80% power, a ratio of schools with WASH programs to non-WASH program schools of 1 : 3 and a detection level of two times the odds ratio (OR), design effect 1.5 and a 10% non-response rate. The required sample size was determined to be 693 (174 from schools with WASH programs and 519 from schools without WASH programs).

A multi-stage sampling procedure was employed to select study participants. First, all primary schools in the Habru District were categorized into WASH-implementing and non-WASH-implementing schools. Then, 30% of primary schools from each category were selected using the lottery method and included in the sample (three with WASH programs and eight without WASH programs). Afterward, all school children aged 8–15 years from these 11 schools were identified, and 575 students in WASH schools and 2178 students in non-WASH schools were listed as a sampling frame. Then, a sampling interval (K) of N/n was computed and the first student was selected using the lottery method and every third student in WASH schools and fourth student in non-WASH schools was selected until the required sample size was achieved.

Figure 1: Schematic presentation of sampling procedure.

Figure 1: Schematic presentation of sampling procedure.

Study variables

The outcome variable was the occurrence of a diarrhea episode during the 2 weeks preceding the survey (yes/no). Independent variables included the following: (i) demographic factors (age, sex, grade, educational status of the mother, educational status of the father); (ii) WASH-related awareness factors (awareness of the causes and the means of transmission and prevention of diarrhea); (iii) WASH-related practice factors (self-reported latrine utilization at school and home, self-reported hand-washing practice at school at critical times); and (iv) enabling factors (such as hygiene education in the school, availability of water throughout the year in the school, cleanliness of the school latrine, availability of a latrine at home, regular hygiene inspection in the school).

Operational definitions

Acute diarrhea: Diarrhea was defined as the passage of three or more abnormally loose, watery, or liquid stools over 24 hours32.

Improved water source: A water source was considered to be improved if it was collected from protected springs and/or wells, a pipe or a distribution point.

Latrine utilization: Latrine utilization was defined as regular and consistence use of a latrine at home/school.

Hand-washing at critical times: Critical times for hand-washing included after visiting the latrine and before eating food. Hand-washing was defined as using clean water and soap or ash.

Data collection and analysis

Four trained diploma nurses used a pre-tested structured questionnaire to collect data by face-to-face interview. A checklist was used to observe and assess the WASH condition of the studied schools. The data collection tools were developed by reviewing relevant literature10,18. The data collection tools were first prepared in English then translated into Amharic (the local language), then back-translated to English to ensure consistency and to enhance reliability. The questionnaire was pre-tested on a different group that was 10% of the actual sample size. One day of training was given to data collectors and supervisors before data collection. The data collection process was closely supervised daily by two environmental health officers.

Data were entered using EpiData v3.1 statistical software (EpiData Association; http://www.epidata.dk/download.php) and exported into the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v20.0 for analysis (SPSS; http://www.spss.com). Frequency distributions and χ2 tests were used to present important variables. A χ2 test was used to assess if there was any significant difference in the prevalence of diarrhea among school-going children in WASH-implementing and non-WASH-implementing schools; the two categorical variables were prevalence of diarrhea (yes/no) and type of school (WASH-implementing or non-WASH implementing). Binary logistic regression analysis was used to identify the independent predictor factors for acute diarrhea among school-going children in WASH-implementing and non-implementing schools. Finally, multivariate binary logistic regression analysis was performed to control for the possible confounding effect. The Hosmer–Lemeshow statistic was used to test the goodness-of-fit of the final model. Adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with corresponding 95%CI was used to estimate the association between dependent and independent variables, and a p-value ≤0.05 was used to declare statistical significance.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the health research ethical review committee of Mekelle University College of Health Science (ERC 06133/2016). A formal letter was obtained from the district education office, and the assent of school directors and school committee assigned by families of the students was obtained. Both oral and written consents were obtained from the study participants before the interview and, at all levels, confidentiality was assured. After data collection, health education on WASH issues was provided to all students. During data collection, children who had diarrhea were immediately referred to a nearby health institution for management.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants

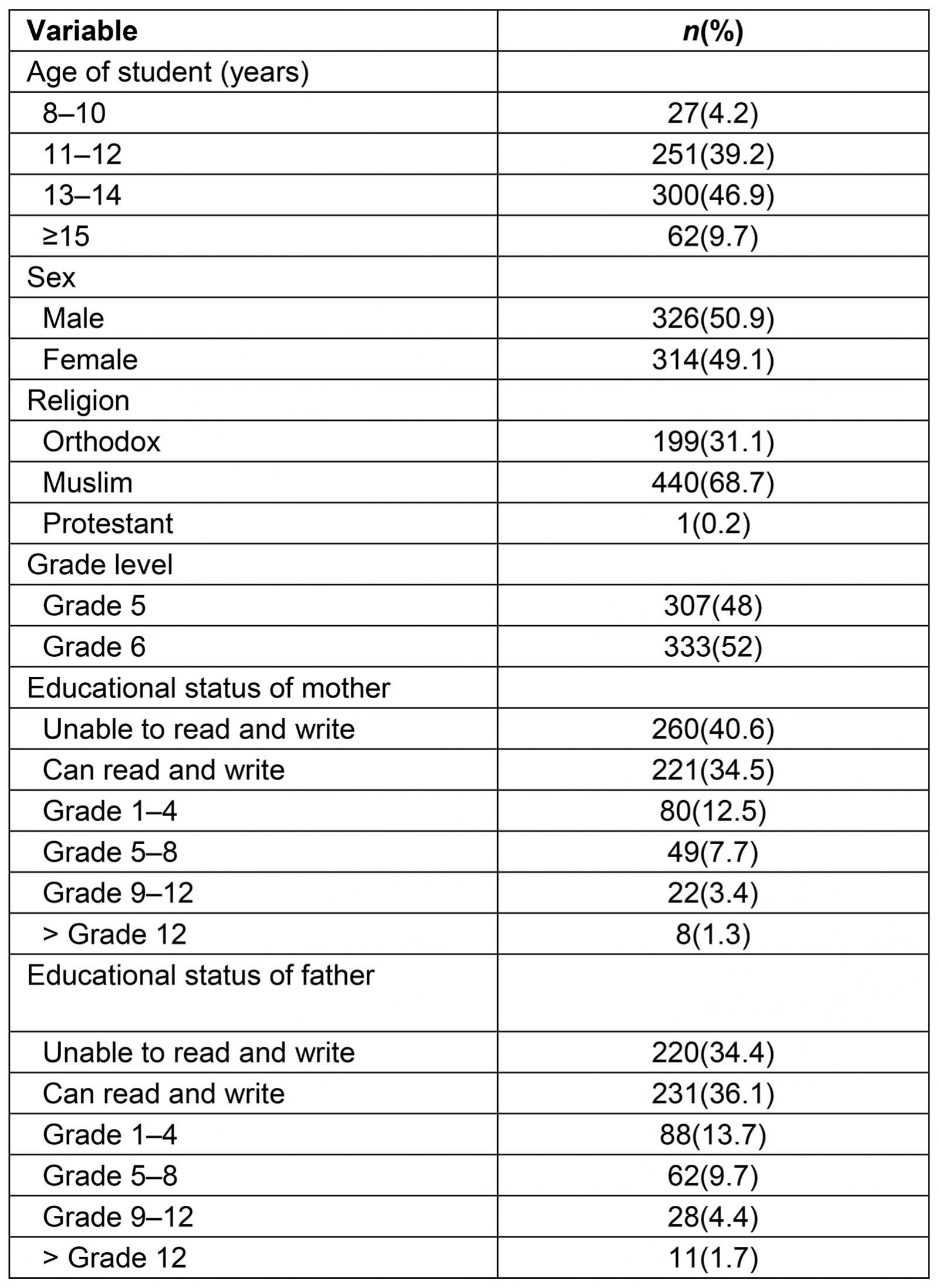

In total, 640 school children (160 from schools with WASH programs and 480 from schools without WASH programs) participated in the study, with a response rate of 92.35% of the targeted children. Among these, 307 (48%) students were from fifth grade and 333 (52%) students were from sixth grade. The sex composition of the sampled school children was overweighed by male students (326/640; 50.9%). In this study, 300 (46.9%) of the students were in the age group of 13–14 years. Regarding the educational status of parents, 260 (40.6%) mothers had not learned to read and write and 220 (34.4%) of the fathers had not attended formal education and were unable to read and write (Table 1).

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics of students in Habrudistrict primary School, North Wollo, Ethiopia, January–March 2016 (n=640)

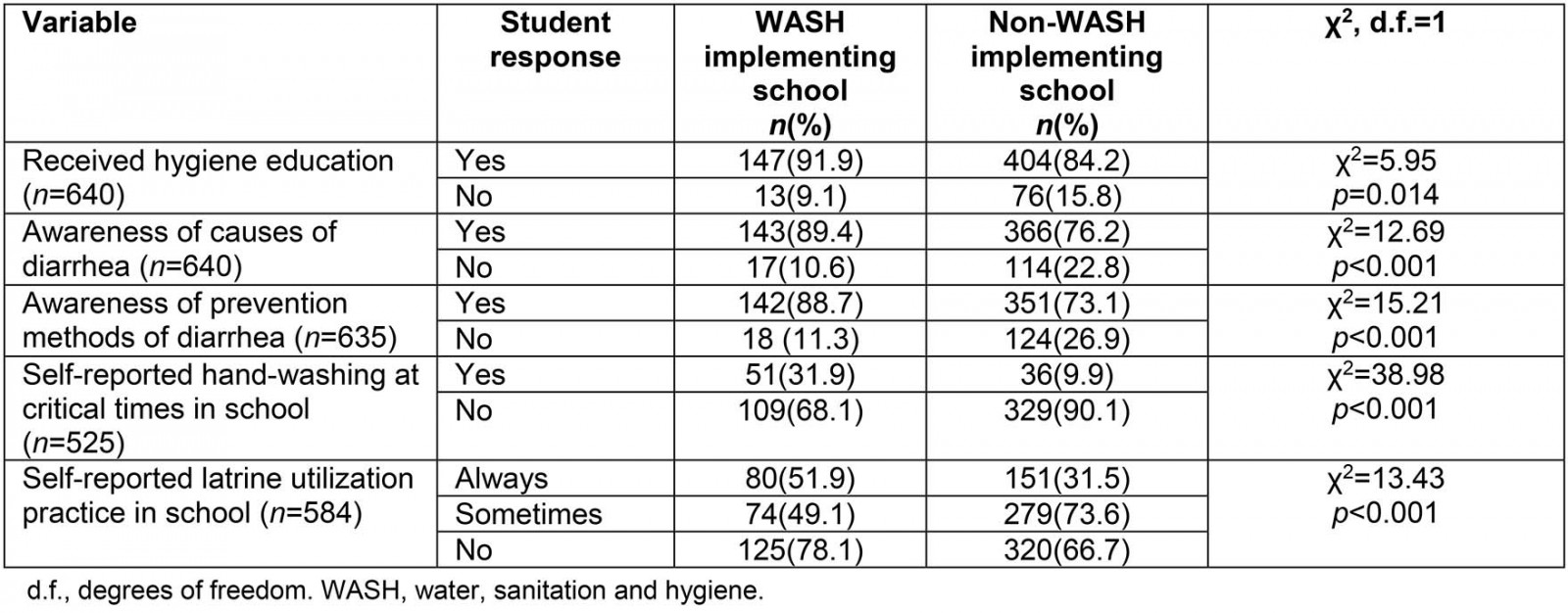

Hygiene education, awareness and practices of students

In this study, 551 (86.1%) of school children reported that they received hygiene education from school teachers, 91.9% in schools with WASH programs and 84.2% in schools without WASH programs. About three-quarters of students in schools without WASH programs knew about the causes (76.2%) and prevention measures (73.1%) for diarrhea, respectively. In WASH-implementing schools, 143 (89.4%) and 142 (88.7%) of students knew about the causes and measures for diarrhea prevention respectively. The study also found in that in WASH-implementing schools 109 (68.1%) of the students did not practice hand-washing at critical times while they were at school (Table 2).

Table 2: Comparison of hygiene education, knowledge and practices of students among WASH-implementing and non-WASH-implementing primary schools of Habru District, North Wollo, Ethiopia, January–March 2016

Prevalence of diarrhea

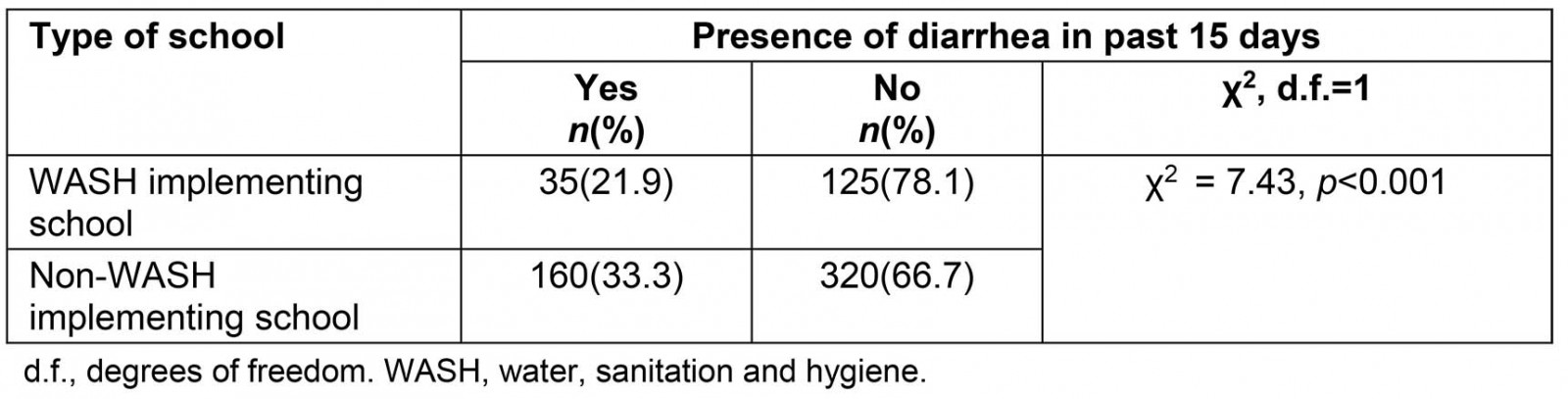

A total of 160 students (33.3%) (95%CI: 29.0–37.5%) were from schools without WASH programs and 35 (21.9%) (95%CI: 15.6–28.1%) were from schools with WASH programs. The overall prevalence of diarrhea in school-going children during the 15 days preceding the survey was 195 (30.5%) (95% CI: 26.9–34.1%). The proportion of diarrheal diseases was significantly higher in students attending schools without WASH programs than students in schools with WASH programs (χ2=7.43 (degrees of freedom 1), p<0.001) (Table 3). Children attending non-WASH-implementing schools were more likely to have had diarrhea in the 2 weeks preceding the survey compared with those attending WASH-implementing schools (OR: 0.56, 95%CI: 0.36–0.85).

Table 3: Comparison of type of school and occurrence of diarrheal diseases in Habru District, North Wollo, Ethiopia, January–March 2016 (n=640)

Factors associated with diarrhea prevalence

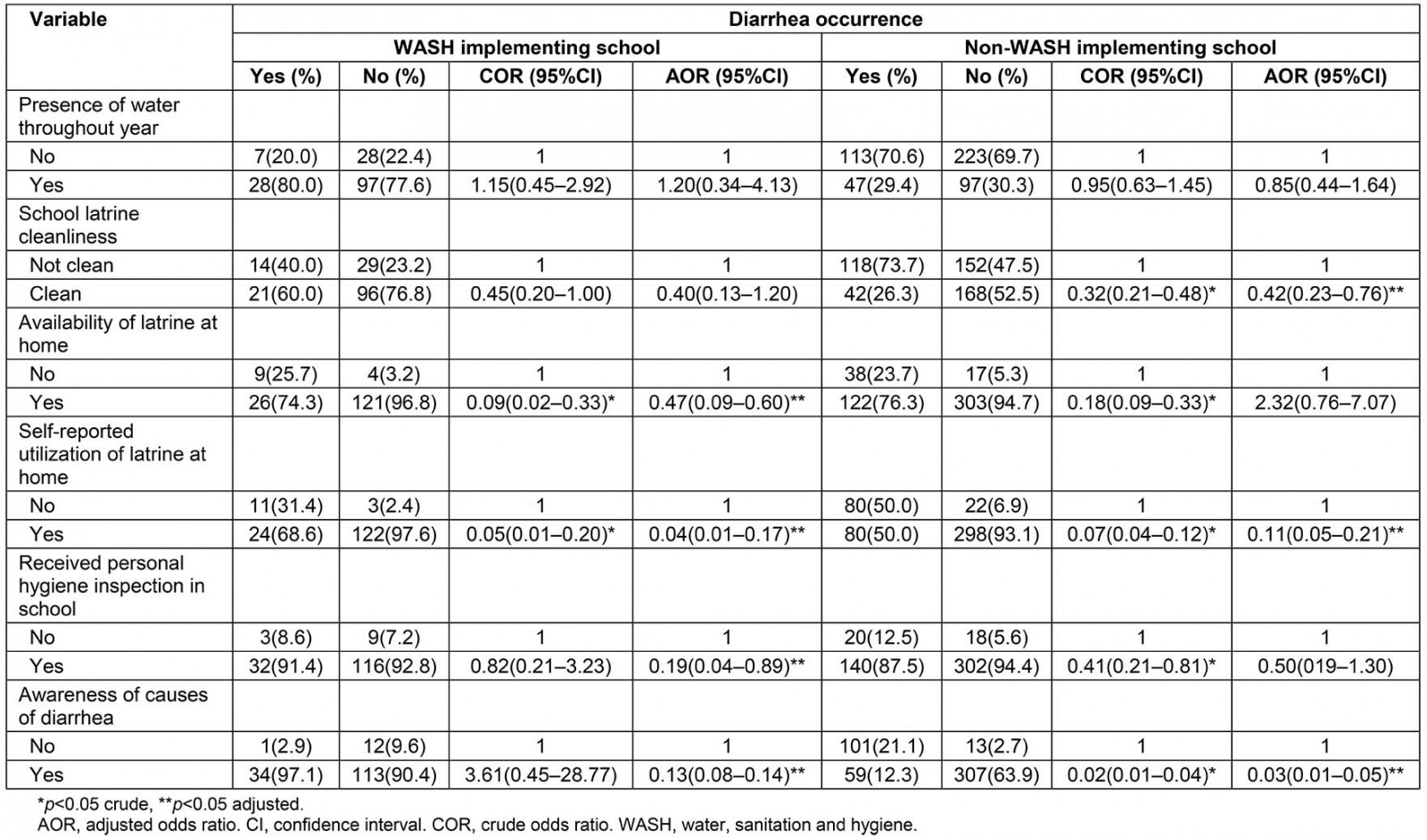

Table 4 shows factors associated with diarrheal diseases among children attending schools with WASH programs and schools without WASH programs. In WASH-implementing schools, factors associated with decreased odds of diarrheal diseases among students included availability of a latrine in the home (AOR: 0.47, 95%CI: 0.09–0.60), self-reported latrine utilization at home (AOR: 0.04, 95%CI: 0.01–0.17), received personal hygiene inspection in the school (AOR: 0.19, 95%CI: 0.04–0.89), and awareness about causes of diarrhea (AOR: 0.13, 95%CI: 0.08–0.14). In non-WASH-implementing schools, factors associated with decreased odds of diarrhea included school latrine cleanliness (AOR: 0.42, 95%CI: 0.23–0.76), self-reported latrine utilization at home (AOR: 0.11, 95%CI: 0.05–0.21), and awareness about the causes of diarrhea (AOR: 0.03, 95%CI: 0.01–0.05). Students attending schools with WASH programs but no access to a latrine at home were 10 times more likely to have had diarrhea in the 2 weeks preceding the study than those with access to a latrine at home (AOR: 10.47, 95%CI: 2.99–36.60).

Table 4: Comparison of factors associated with diarrhea occurrence among students in WASH-implementing and non-WASH-implementing primary schools of Habru District, Amhara, Ethiopia, January–March 2016 (n=640)

Discussion

This study assessed the prevalence of diarrheal disease among primary school children aged 8–15 years in the Habru District of Ethiopia and found the overall prevalence of diarrhea to be 30.5%. This result is higher than the study conducted in Assossa District (Ethiopia) and Babile Town (Ethiopia)33,34. However, the overall prevalence was lower than found in the studies conducted in primary schools of Motta Town (Ethiopia) and Khartoum (Sudan)28,35. The present study clearly showed that there is a relatively low prevalence of diarrhea among students in WASH-implementing schools (21.9%) compared with non-WASH-implementing schools (33.3%) and this difference might be due to the impact of the school WASH program. There was a significant difference in WASH facilities such as improved water supply and sanitation facilities between the schools with and without WASH programs. In addition, WASH interventions in schools can influence diarrheal outcomes among children through the teaching of hygienic practices and behaviors. Other studies have shown that school WASH interventions can reduce diarrheal diseases among school-going children19,20,36. Studies from Cambodia and Kenya reported a significant positive effect of sanitation practices on reducing diarrhea prevalence37,38.

A cluster-randomized trial conducted in Kenya provides ample evidence that school WASH interventions may reduce diarrhea and gastrointestinal-related clinic visits among children younger than 5 years20. A meta-analysis in 2014 showed that the overall effect of access to an improved sanitation facility on reduction in diarrhea morbidity was 28%38. More recent studies have also emphasized that the provision of adequate WASH facilities in schools has a crucial positive effect on health and educational outcomes and school attendance19,20,24,39,40. Good sanitation and hygiene practices are potentially important in controlling parasitic worms among school children40. School WASH improvements can result in improved school attendance for girls19. A cluster-randomized controlled trial conducted in Chinese primary schools showed that a school-based hand-washing program has been decreasing both absenteeism and length of absence for students41. In line with this study finding, there is good evidence that WASH interventions, hygiene and hand-washing decrease diarrhea42.

Cleanliness of school latrine facilities had a significant association with the prevalence of diarrheal diseases in the study area. Students in schools with clean latrines were less likely to develop diarrheal diseases than students in schools without clean latrines. The reason for this may be that students who spend their school time in schools with clean latrines might be attracted to use the latrine facility and may develop the habit of utilizing the latrine regularly and hygienically. In line with this, studies have shown that disposing of feces safely can reduce diarrhea, and this can be achieved when latrines are kept clean43,44.

Latrine utilization by school children at their home was one of the major hygiene practice factors that increased or decreased the prevalence of diarrheal diseases. In this study, regardless of whether the school had a WASH program or not, students utilizing a latrine in their home were less likely to develop diarrhea than students who did not utilize a latrine in their home. This finding was consistent with the study in Motta Town (Ethiopia)28. In addition, students who had an awareness of the causes of diarrhea were less likely to develop diarrheal diseases than students without awareness. Similarly, reduced risk of parasitic infections was observed in children with substantial knowledge of hygiene and sanitation practices45.

This study has several limitations. First, due to the cross-sectional nature of this study design, temporal relationships cannot be established between the explanatory and outcome variables. Being a cross-sectional study rather than using a longitudinal design, the study is limited in assessing the long-term impact of school-based WASH interventions. Second, the study does not allow for seasonal changes in diarrhea prevalence. Third, common issues related to self-reported practices and recall bias should not be ignored. Fourth, the study didn’t use multilevel analysis, which is the ideal alternative to address nested data since there might be a dependency between school-related factors and the presence of diarrhea at an individual level. Despite this limitation, the study detected a significant difference in diarrhea prevalence among students from schools with WASH programs and without WASH programs. Last, the lack of standardized questionnaires with acceptable reliability and validity for assessing WASH interventions in Ethiopia limits the findings of this study. In future studies, researchers are recommended to use a strong design such as observational study designs to assess the impact of school WASH programs.

Conclusion

The prevalence of diarrheal disease among students in schools without WASH programs was higher than in students attending schools with a WASH program. Environmental factors (cleanliness of the school latrine), hygiene practices (latrine utilization by students at their homes) and students’ awareness about the causes of diarrheal diseases were factors associated with reduced prevalence of diarrheal diseases among school-going children. Hence, scaling up WASH programs across all rural primary schools along with awareness creation activities on latrine utilization and hygienic behavior at school and in the broader community are strongly recommended.

Acknowledgements

We thank the students who volunteered and took their time to give us all the relevant information for the study. We also thank data collectors, supervisors, school directors and school committee members.

References

You might also be interested in:

2012 - Prevalence of low back pain among peasant farmers in a rural community in South South Nigeria