Introduction

Tobacco smoking is the leading avoidable cause of diseases and early death in Brazil and worldwide1. It is a public health problem, accounting for the highest morbidity and mortality rates and for some 70% of healthcare expenditure in Brazil, and this trend is increasing2.

Smoking is among the factors that increase the risk of developing diseases at more advanced ages, and rates have been growing rapidly in Brazil3. The need for research focused on this group can be justified by studies that identify elderly people as those who most demand attention from health institutions, because they are the most affected by diseases and morbidities caused by tobacco use, which can compromise their health4,5.

Studies with rural elderly people show high tobacco smoking prevalence, with 22.1% in India, 20.8% in China and 19.1% in the USA6-8. According to a survey specific to tobacco smoking, in Brazil tobacco smoking prevalence is greater in rural areas (20.4%) than in urban areas (16.6%)9. The results are similar to findings for the research studies on smoking in the general population10. These findings may be because elderly people living in rural areas tend to have lower levels of schooling and income, as well as less access to health services9.

Although tobacco smoking among the Brazilian adult population is monitored by surveys such as surveillance of chronic diseases by telephone survey (VIGITEL)11, the data obtained relates to people living in urban areas. Very little is therefore known about tobacco smoking prevalence and associated factors among elderly people living in Brazilian rural areas. As such, the objective of this study is to assess tobacco smoking prevalence and associated factors among the elderly in the rural area of the municipality of Rio Grande, Rio Grande do Sul (RS).

Methods

Study setting

This study is part of a larger study that evaluated the health conditions of the Rio Grande population. Its general objective was to know basic health indicators and the pattern of morbidity and use and access to health services in three population groups living in this area: children aged less than 5 years and their mothers, women of childbearing age (15–49 years) and the elderly (60 years or more).

This was a cross-sectional, population-based study conducted with individuals aged 60 years or more in the municipality of Rio Grande, RS. Located in the southernmost region of the state, 300 km away from the state capital of Porto Alegre, the municipality has an estimated population of 209 378, of whom some 8500 individuals live in its rural areas12.

According to Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics data, the rural area of Rio Grande comprised 24 census tracts and approximately 2700 permanently inhabited households. Data collection took place between April and October 2017.

Study sample

Systematic sampling was done of 80% of permanently inhabited households of the rural area of Rio Grande, RS, by drawing a number between 1 and 5. The number drawn corresponded to the household to be skipped. For example, if number 3 was drawn, any household number 3 out of a sequence of five households was not sampled (it was skipped). This procedure ensured that four in every five households were sampled.

In Brazil, as per the WHO definition, an elderly person is considered to be someone who is aged 60 years or more13. As such, all individuals living in the selected households and who were in this age range were eligible to take part in this study and were therefore invited to do so.

Upon acceptance, the supervisor introduced the interviewer who, after the informed consent form had been read and signed, administered the questionnaire corresponding to the age range of the respondent. The head of the household also answered the block of questions about the household. Where an elderly person was unable to answer the questions, the family member or carer in charge of them was interviewed.

At the end of the field work, 4189 households had been identified in the rural area of the municipality of Rio Grande, being 2669 permanent households and 1419 households either unoccupied or with temporary inhabitants (only at weekends/holidays). It was not possible to obtain information from dwellers or neighbors of 101 households, even after three or more attempts.

In the 2669 households that had permanent dwellers, 1351 elderly people were identified, 1131 of whom were included in the sample. A total of 1030 elderly people were interviewed.

The number of elderly people interviewed is sufficient to examine estimated tobacco smoking prevalence of 15%, with a 95% confidence level, a margin of error of two percentage points and an additional 10% for losses/refusals. With regard to studying associated factors, this number guarantees minimum statistical power of 80%, taking a prevalence ratio of 1.8 and an exposed/non-exposed ratio of 1:4 to 5:1, and an additional 15% to adjust for confounding factors.

Data collection procedures

Two instruments were used for data collection. The first, a household questionnaire, was answered by heads of household and assessed family socioeconomic characteristics. The second, specifically for elderly people, assessed aspects related to behavior, health and use of health services. The questionnaires were administered using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) mobile application on tablet computers14. All interviewers underwent a 40-hour training course.

The variables used in this study were sex, age, skin color, marital status, schooling, religion, work, alcoholic beverage consumption and tobacco smoking (‘never smoked’, ‘former smoker’, ‘smoker’). Smokers were considered to be individuals who reported smoking one or more cigarettes a day for the previous month or longer, and former smokers were taken to be those who had stopped smoking more than a month previously. Tobacco smoking characteristics among elderly smokers and former smokers were ‘smoker for how long (years)’, ‘number of cigarettes/day’, ‘smoked for how long (years)’ and ‘how long ago stopped smoking (years)’.

Data analyses

Data analysis was performed using the Stata v13 statistical software package (StataCorp; http://www.stata.com). First, the proportions of each of the categories of the independent variables of interest were calculated. Second, tobacco smoking prevalence for each of the exposure categories was calculated using Fisher’s exact test.

Crude and adjusted Poisson regression with robust variance was used to analyze associated factors, calculating the prevalence ratios (PRs) and respective 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The adjusted analysis followed a hierarchical model15 with four levels. The first level contained the age, sex and skin color variables, and the second level contained the schooling, marital status and work variables. The third level contained income in quartiles and religion, and the fourth level contained alcohol consumption in the previous week. Variables with p<0.20 were kept in the model and associated variables were considered to be those with p<0.05 in the Wald heterogeneity or linear trend tests.

Ethics approval

This research project was approved by the Federal University of Rio Grande Research Ethics Committee (report no. 51/2017, process no. CAAE 23116.009484/2016-26). All participants signed a free and informed consent form. The confidentiality of all information provided was ensured, as was the possibility of being able to leave the study at any time.

Results

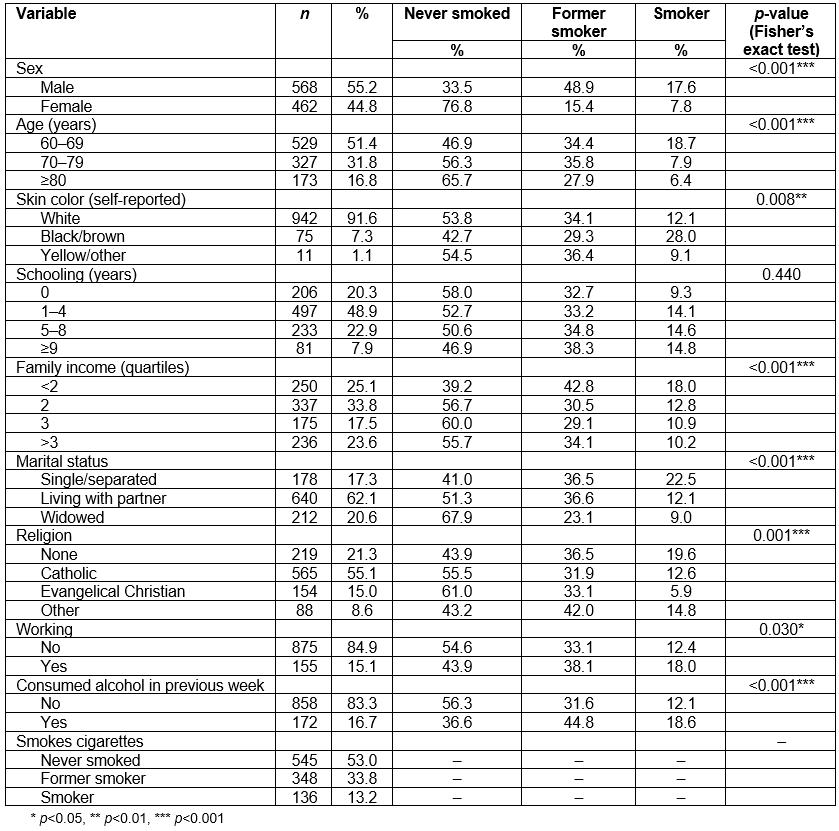

Of the 2669 inhabited households, 1351 elderly people were identified, 1131 were sampled and 1030 responded (losses and refusals 8.9%). The majority of the sample comprised elderly males (55.2%), people in the 60–69 year age range (51.4%), with white skin color (91.6%) and living with a partner (62.1%). Almost half stated having between 1 and 4 years of schooling (48.9%), 33.8% were in the second income quartile and 84.9% did not undertake paid work. More than half stated they were Catholic (55.1%) and 16.7% had consumed alcoholic beverages in the previous week. A total of 33.8% were former tobacco smokers and 13.2% were smokers (Table 1).

Tobacco smoking prevalence was higher among males (17.6%), people aged 60–69 years (18.7%), with black/brown skin color (28.0%), lower income (18.0%), single/separated (22.5%), working (18%) and who had consumed alcohol in the previous week (18.6%). Evangelical Christians smoked less than individuals of other religions or with no religion (Table 1).

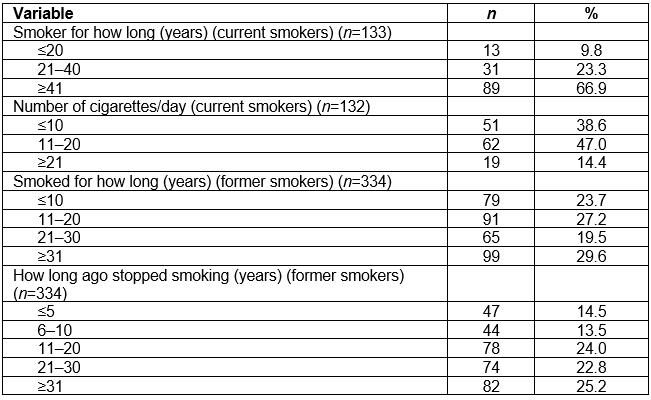

The majority of current smokers had smoked for 41 years or more (66.9%) and 47.0% smoked 11 cigarettes or more per day (Table 2). The majority of former smokers had smoked for 31 years or more (29.6%) and had stopped smoking more than 31 years ago (Table 2).

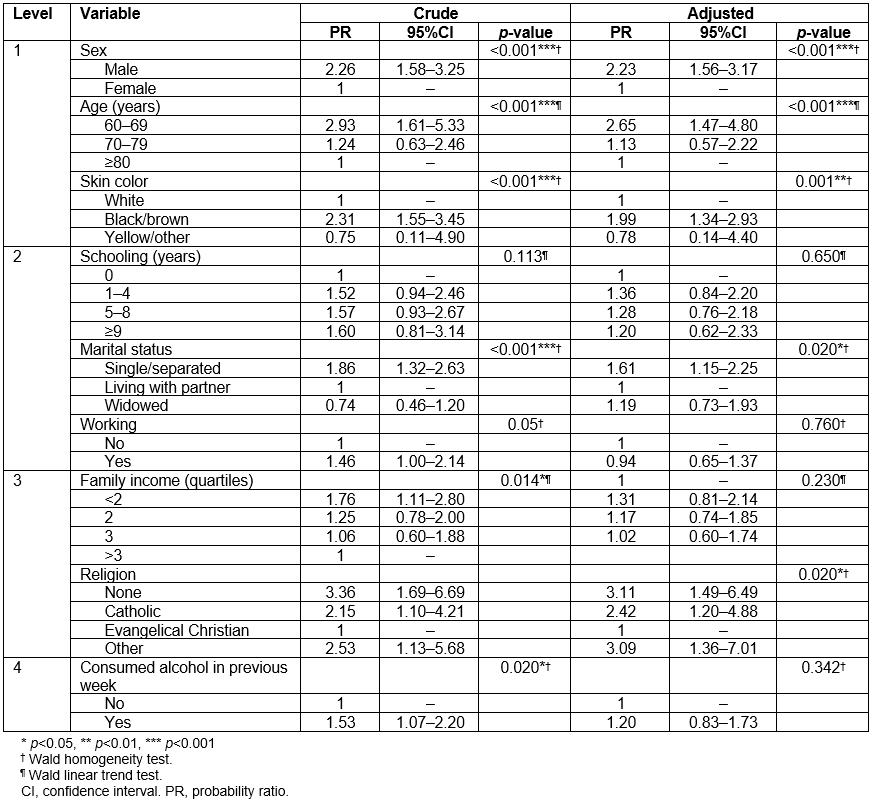

Being male (PR=2.23, 95%CI=1.56–3.17), being aged 60–69 years (PR=2.65, 95%CI=1.47–4.80), having black/brown skin color (PR=1.99, 95%CI=1.34–2.93) and being single/separated (PR=1.61, 95%CI=1.15–2.25) had statistically significant associations with the outcome after adjustment. Individuals with no religion (PR=3.11, 95%CI=1.49–6.49), Catholics (PR=2.42, 95%CI=1.20–4.88) and people of other religions (PR=3.09, 95%CI =1.36–7.01) had greater risk of smoking when compared to evangelical Christians (Table 3).

Table 1: Tobacco smoking characteristics and prevalence among elderly people living in the rural area of the municipality of Rio Grande, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, 2017 (N=1030)

Table 2: Tobacco smoking characteristics among elderly smokers and former smokers living in the rural area of the municipality of Rio Grande, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, 2017

Table 3: Crude and adjusted analysis of factors associated with current tobacco smoking among elderly people living in the rural area of the municipality of Rio Grande, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, 2017 (N=1030)

Discussion

Tobacco smoking among the elderly living in the rural area of Rio Grande, RS is associated with the male sex, being aged 60–69 years, having black/brown skin color and being single/separated, and is also associated with religion.

Tobacco smoking prevalence found in this study (13.2%) is similar to that found in urban areas of the state of São Paulo (12.2%)16 and by the National Household Sample Survey (PNAD)17, which assessed tobacco smoking prevalence in the rural areas of large municipalities (13.1%). These results show that tobacco smoking prevalence rates among elderly Brazilians are lower than those found in Canada (30.7%)18, China (28.4%)5, India (22.1%)6 and the USA (19.4%)19, and higher than those in Poland (9.3%)20, France (8.3%)21 and Italy (7.1%)22.

The lower prevalence found by this study, as well as in other countries, may be the result of legislation and increased taxation on tobacco and monitoring, in addition to educational/preventive policies and measures to scale up smokers’ access to treatment23. Many countries have joined the WHO convention on tobacco control and have adopted stringent policies to protect the population from the adverse effects of cigarettes24.

Brazil has stood out, as an example to the world, in tackling tobacco smoking. Internationally recognized by the Bloomberg Foundation Awards25 for its initiatives in organizing tobacco monitoring and surveillance, Brazil has made a combined effort to reduce the prevalence of tobacco use even further.

The association between males and tobacco smoking among elderly people living in rural areas has been reported by studies conducted in the USA8, India22 and China20. This association is explained by historical and sociocultural factors that placed cigarettes as a symbol of male status and social power, strongly relating them to masculinity and to personal/professional success26,27.

The habit of smoking was found to be most prevalent among elderly people aged 60–69 years, which is similar to prevalence found in other studies6,16,26. This result may arise from the appearance of diseases that lead older people to stop smoking and to adopt healthier behaviors16.

Elderly single/separated people are at greater risk of tobacco smoking16,26. Hypotheses have been raised to explain this association and they highlight that single/separated people tend towards solitude and isolation, thus being more vulnerability in terms of continuing to smoke compared to people who are married or living with a partner and who receive greater social support, which favors giving up smoking28.

The association between skin color and tobacco smoking is as yet little discussed in the literature. However, studies indicate that people with black and brown skin color are more vulnerable to tobacco consumption, because of less favorable socioeconomic conditions, difficulty in giving up nicotine and the scarcity of resources for so doing29.

Tobacco smoking prevalence among evangelical Christians was considerably less than for followers of other religions. Practicing a faith has been said to have a positive effect on some behaviors and favors keeping away from tobacco and other drugs16. As such it is plausible that values and teachings cultivated by the evangelical Christian faith may have greater influence over these behaviors, when compared to other religions, thus favoring self-control and less possibility of harmful conduct30.

This is the first population-based study with elderly people in the rural area of Rio Grande. The findings may be useful for local government managers, as well as serving as the basis for posterior trend analyses and monitoring of tobacco use in rural areas.

The findings show that tobacco smoking is frequent and of long duration and that, therefore, local health services suffer the impacts of diseases associated with tobacco use. Practices intended to encourage people to give up smoking need to be promoted as a means of preventing and/or minimizing the burden of diseases stemming from tobacco smoking. This is particularly important in rural areas, where traditionally access to health services is more difficult. To this end, the need exists to strengthen primary healthcare services, especially the Family Health Strategy, which has 100% coverage of the rural population of the municipality of Rio Grande, RS.

Limitations of this study include its cross-sectional design, which examines predictors and outcomes only at that moment in time and whereby cause/effect cannot be examined; lack of an instrument to assess the degree of nicotine dependence among the elderly people interviewed; and obtaining reported information about tobacco smoking characteristics that may be subject to memory bias.

Conclusion

This article presents the results of a study of a representative sample of elderly people living in the rural areas of a municipality in the far south of Brazil. Tobacco smoking prevalence and associated factors were identified among a population scattered over a huge territory characterized by low population density and places very far from the urban center of the municipality. Tobacco smoking stood out among that population as a relevant public health issue.

Although the prevalence of tobacco smoking found in this study is similar to other national studies with the elderly, tobacco use is still considerable and is among the main causes of avoidable diseases. The importance of this study therefore lies in its being the first conducted with elderly people living in the rural areas of the municipality studied. Its findings can become a tool for planning actions or public policies aimed at promoting behavioral changes that reduce risk factors associated with tobacco smoking among the elderly in rural areas.