Introduction

The unmet needs for family planning are defined as those of the percentage of women who are fecund and sexually active, but do not use any contraception method, or do not want any more children or want to delay the delivery of the next child1. The unmet need for family planning reveals the gap between women’s reproductive intentions and their contraceptive behaviours and is a valuable indicator in monitoring and evaluating family planning programs and for improving access to reproductive health services1,2.

In 2012, approximately 213 million pregnancies occurred worldwide, 85 million (40%) of which were unintended. Of these, 50% ended in abortion, 13% ended in miscarriage and 38% resulted in an unplanned birth3. According to the 2015 Millennium Development Goals Report, the unmet need for family planning worldwide decreased from 15% in 1990 to 12% in 2015. However, these levels were 28% and 24% in Sub-Saharan Africa, 21% and 14% in West Asia, and 22% and 12% in North Africa4. The prevalence of unmet need for family planning has been reported to vary between 20% and 58% in low- and middle-income countries5. According to the 2013 Turkey Demographic and Health Survey (TDHS-2013), the percentages of unmet need among married women in the 15–49-year age group in Turkey were 15%, 8% and 6% in 1993, 2003 and 2013, respectively6.

There is a strong relationship between the status of a woman and her fertility behaviour. The status of a woman in a region can be understood through mechanisms that nurture, protect and reinforce the traditional control of a woman’s body and the inequality between the sexes. Among these mechanisms are social indicators related to family and kinship, such as early marriages, consanguineous marriages, forced marriages, bride prices, honour killings, and the level of women’s participation in social life7,8. The features of a traditional society are retained in rural areas and are found in the eastern and south-eastern Anatolia regions of Turkey, where Kurds make up the largest ethnic group. Women who live in these regions have a low status, and gender inequality is prevalent6. It can be said that in these settlements where male-dominated traditional norms predominantly reign, a woman’s worth is measured in accordance with her fertility7,8. According to TDHS-2013, the levels of unmet need are highest in rural areas and in eastern and south-eastern Turkey where the fertility rate is high, in women with low education and in women having the lowest household income level6. Studies show that women’s use of their reproductive rights is adversely affected by factors such as a low level of education5,9,10, unemployment9, inadequate access to health services5, patriarchal family relations11,12, poverty13, social norms and cultural factors10, religious beliefs10,14-18 and living in urban slum or rural areas5,15,17,19,20.

The aim of this study was to investigate the levels and associated factors of unmet needs for family planning among married women aged 15–49 years living in two settlements: a village inhabited by migrants from rural areas and from the eastern and south-eastern parts of Turkey as well as an urban settlement, both in Karabuk Province in north-western Turkey.

Method

This cross-sectional study was conducted in two settlements in Karabuk Province. One of these two settlements is the village of Cumayani, 15 km from the Karabuk provincial city centre. The people of the village are said to comprise Kurds who were deported from Diyarbakir, a province in the south-eastern Anatolia region of Turkey, and its surrounding areas during the period of the Ottoman Empire. The inhabitants of the village maintain an introverted lifestyle that enables them to preserve their tradition and culture. A family health centre and a primary school are located in the village. The second settlement is Emek, one of 20 urban neighbourhoods in Safranbolu district, which is 8 km away from the Karabuk provincial city centre. Compared to the other districts of Karabuk, the socioeconomic level of Safranbolu is relatively high.

In the study, the sample size was calculated using the sampling method for an unknown population. The sample size was estimated to be 578 (289 from each settlement) according to the standardised medium effect size of 0.3, α error probability of 0.05 and power (1–β error probability) of 0.95. In the study, 594 currently married women aged 15–49 years (298 from Cumayani village and 296 from Emek neighbourhood) were reached. Women who were separated, divorced or widowed were excluded.

In Turkey, the records from primary healthcare centres are the principal resource for obtaining address-based data about married women aged 15–49 years living in small settlements such as neighbourhoods and villages. Since 2011, when the family medicine system was established in the primary healthcare facilities in Turkey, the list-based organisational system has replaced the geographic region-based organisational structure. The addresses of women aged 15–49 years living in the settlements could not be determined and thus a systematic sampling could not be performed because, under the new model, a person could be registered to any family physician working either in his/her place of residence or in another location. Therefore, women were contacted on a household basis. Because the two settlements differed in size, the data were collected from one in every two houses in a row in the village of Cumayani and from one in every five houses in a row in Emek neighbourhood. Of the women aged 15–49 years in each household, only one was interviewed.

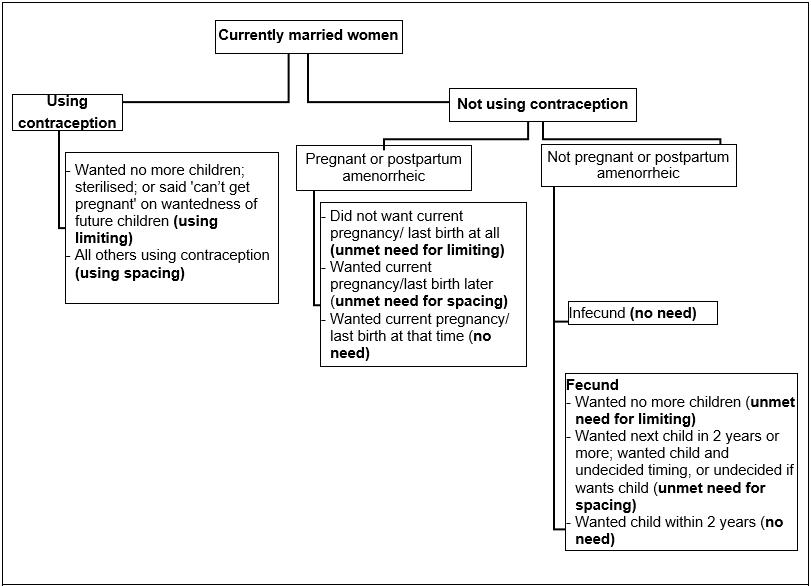

The dependent variable of the study was the participants’ unmet needs for family planning. ‘Unmet needs for family planning’ refers to the proportion of the total number of women who do not use any family planning method, even though they desire to limit or space future births. The unmet needs were determined according to the criteria revised in 20122 and used in the TDHS-2013 report6 (Fig1). The independent variables were the sociodemographic characteristics of the women, which included age, place of residence, monthly household income, type of marriage, family type, education level, employment status, husband’s education level, husband’s employment status and reproductive characteristics. Reproductive characteristics included age at first marriage, age at first pregnancy, total number of pregnancies, number of living children, number of spontaneous and induced abortions, and ideal number of children. The ideal number of children, regardless of the present number of children present, represents the number of children the women wished to have if they were at the beginning of their reproductive life. The data were collected between October 2016 and June 2017 from the women in their homes through face-to-face interviews using a questionnaire containing 54 prepared questions based on the relevant literature. The interviews were conducted by the first author and nine intern nurses. The training of the interviewers was conducted by the first author.

The data were summarised as proportions. The χ2 test was used for comparing the sociodemographic and reproductive characteristics of the women. Both bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to assess factors associated with unmet needs for rural, urban and then all women in the study group. The dependent variable was organised into two categories: code ‘0’ representing no unmet need (the reference category) and code ‘1’ representing unmet need. The variables with a value of p<0.2 in the binary logistic regression analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression model21. The variables in the multivariate analysis were considered as statistically significant at p<0.05. The data analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v20 (IBM; http://www.spss.com).

Ethics approval

Ethical approval and permission to conduct the study were obtained from the Non-Interventional Clinical Research Ethics Board at Karabuk University (26 October 2016, no. 3) and the Karabuk Public Health Directorate (71207605/604.02) respectively. Verbal consent was then obtained from all the women participating in the study to indicate that their participation was voluntary.

Results

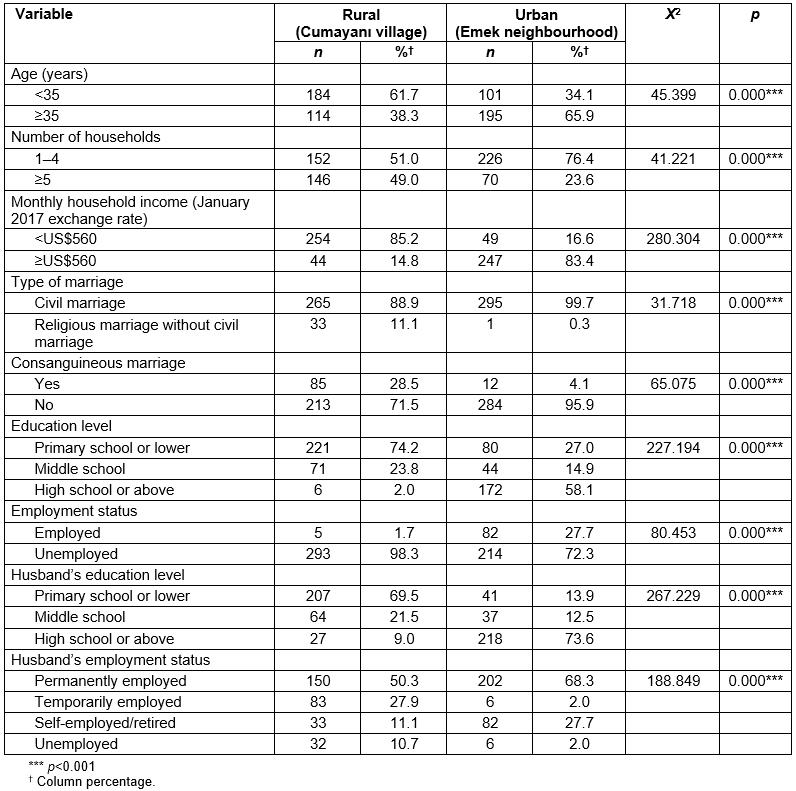

In the study, 594 currently married women (298 from Cumayani village and 296 from Emek neighbourhood) were reached. The ages, household incomes and education levels were significantly lower in the rural women than in the urban women (p<0.001). Thirty-three rural women (11.1%) and only one urban woman were married by way of a religious ceremony (p<0.001). The women and their husbands living in the urban settlement had higher education and employment levels than did the women and their husbands living in Cumayani (p<0.001) (Table 1).

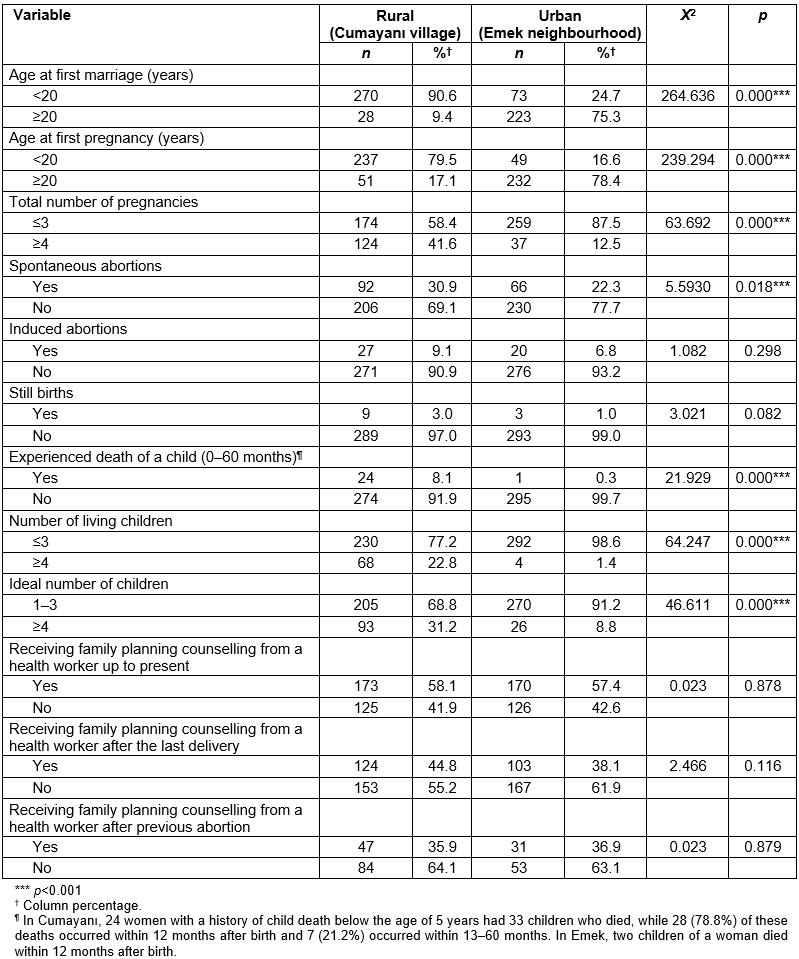

The rural women married and became pregnant at an earlier age than the urban women did (p<0.001). The total number of pregnancies, spontaneous abortions, living children and the ideal number of children were higher in Cumayani than in Emek neighbourhood. The number of women with a history of child deaths under 5 years was 24 (8.1%) in Cumayani, while it was only 1 (0.3%) in Emek neighbourhood (p<0.001). There was no difference between the two settlements in receiving family planning counselling (Table 2).

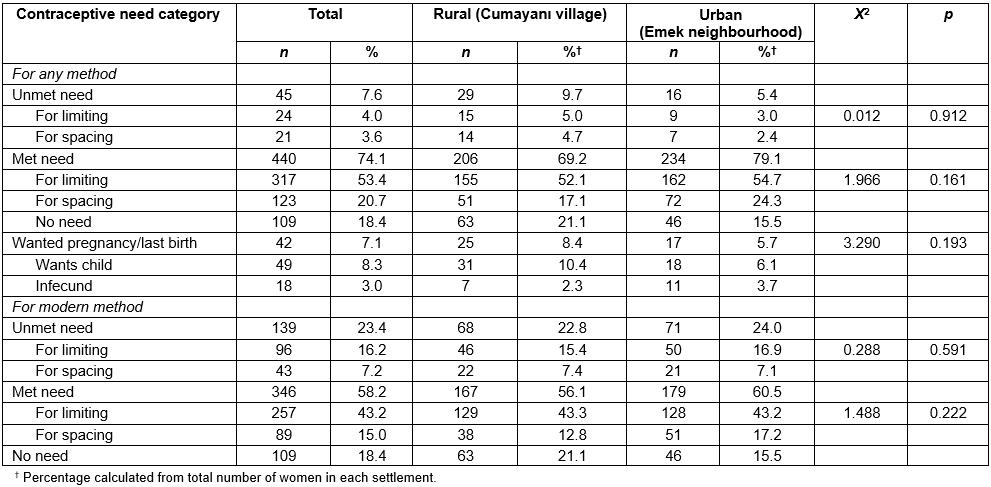

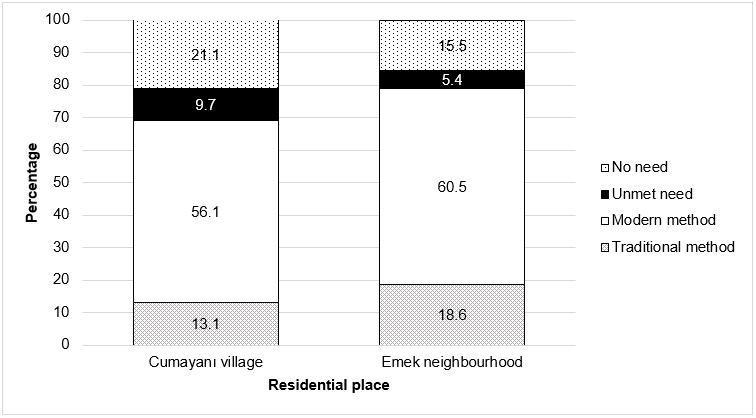

The level of unmet need for any family planning method was 9.7% for the rural women and 5.4% for the urban women. The level of unmet need for the modern method was 22.8% for the rural women and 24.0% for the urban women. There was no statistically significant difference between the two regions in terms of the percentages of met and unmet needs for spacing or limiting childbirths. Moreover, there were no significant differences between the two settlements in terms of the percentage distributions of subgroups in the ‘no need’ category (Table 3, Fig2). The percentages of unmet need, met need and no need for any family planning method among all the participants were 7.6% , 74.1% and 18.4%, respectively. The percentages of unmet need and met need for the modern family planning method were 23.4% and 58.2%, respectively (Table 3).

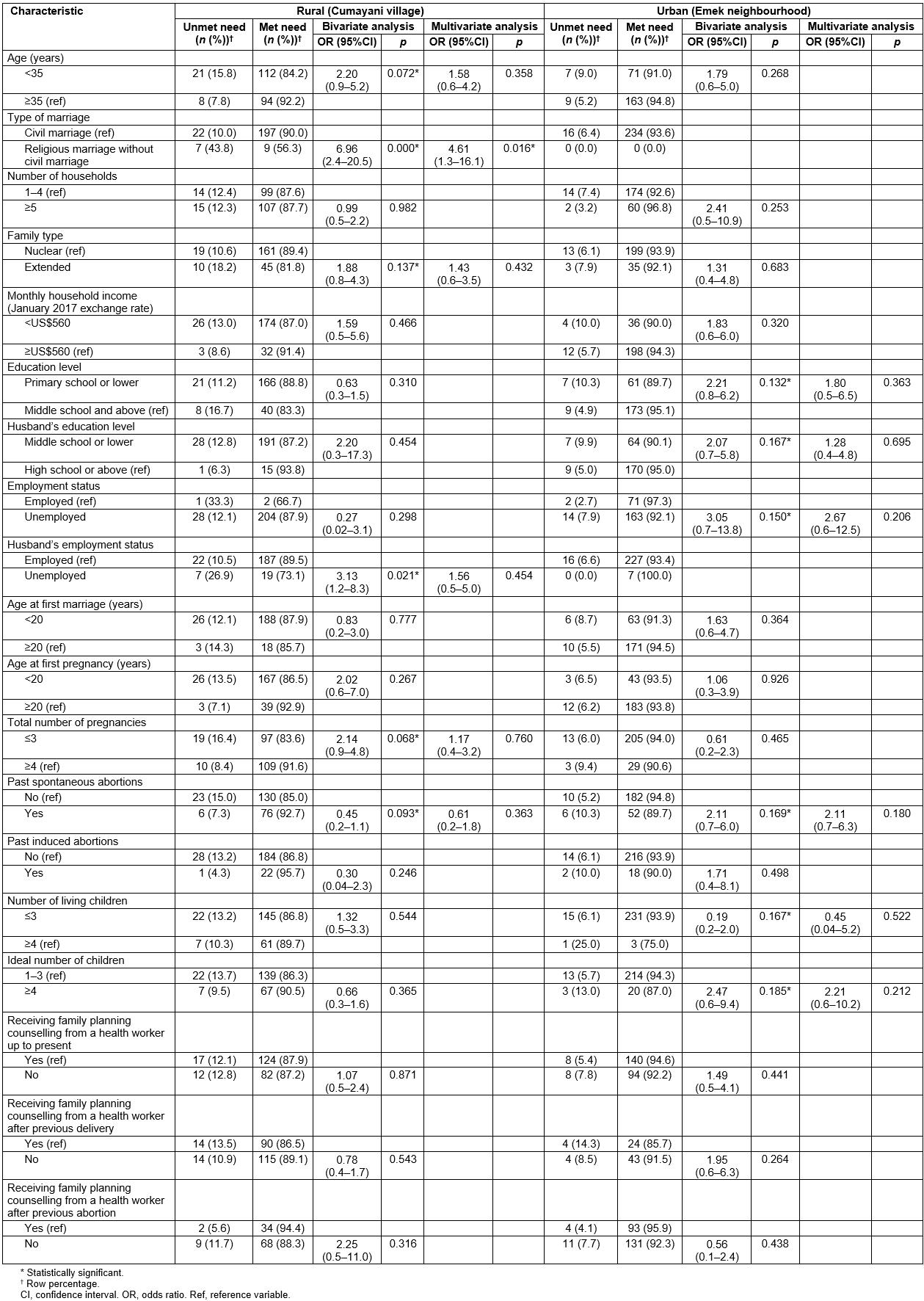

Table 4 shows the results of bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses of independent variables associated with the level of unmet need in each settlement. The bivariate analysis demonstrated that in Cumayani village the variables with p<0.2 were age, marital status, family type, husband’s employment status, total number of pregnancies and past spontaneous abortions. Among the variables included in the multivariate analysis, the variable ‘religious marriage without civil marriage’ (married by way of only a religious ceremony) increased the unmet need 4.6 times (p=0.016). Other variables did not affect unmet need (p>0.05) (Table 4).

In Emek neighbourhood, the variables included in the multivariate analysis were a woman’s education level, husband’s education level, woman’s employment status, husband’s employment status, past spontaneous abortions, number of living children and ideal number of children. No variable was significant in multivariate analysis (p>0.05) (Table 4).

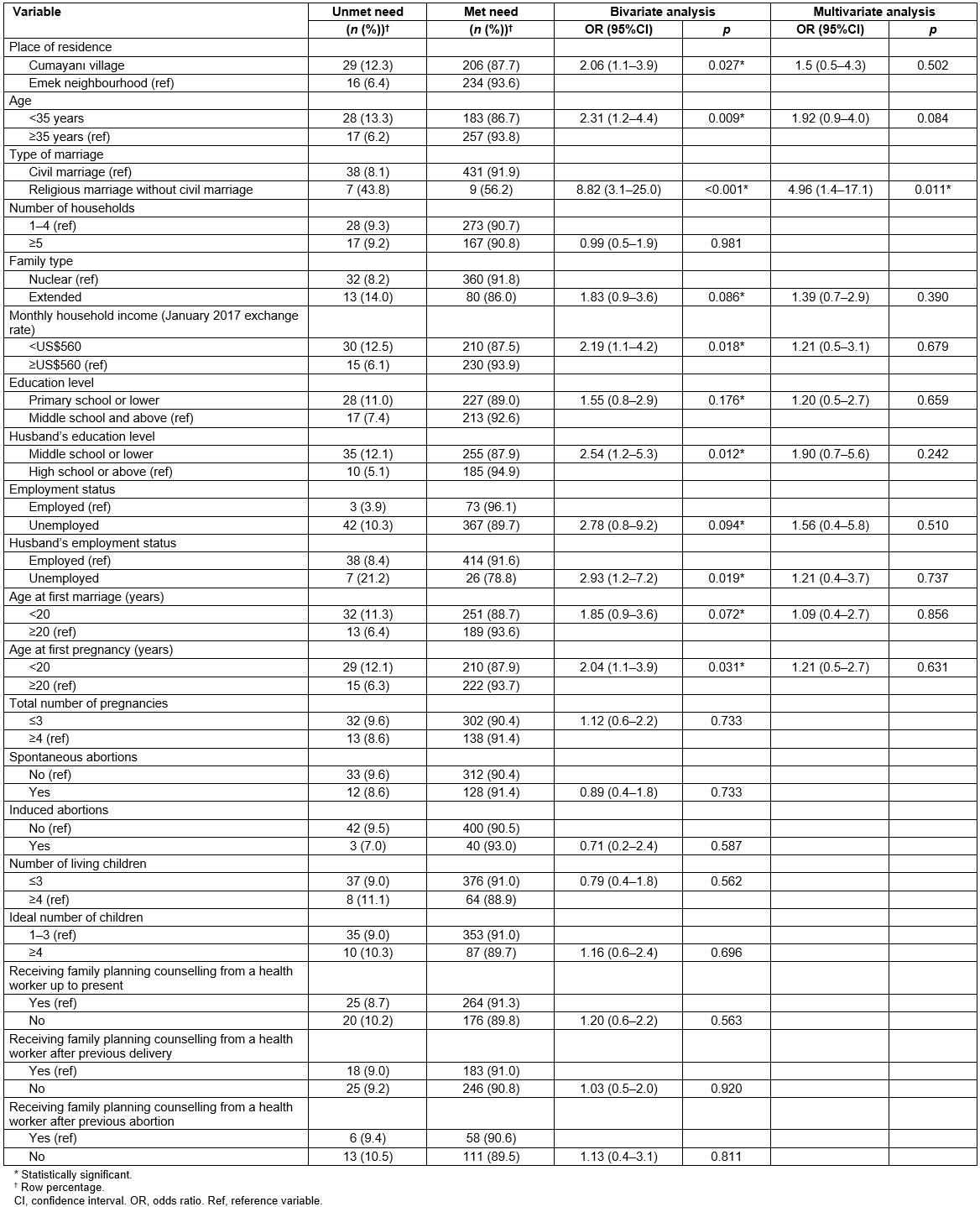

In the bivariate analysis including all the participating women in the study, the variables of living in Cumayani village (p=0.027), being younger than 35 years (p=0.009), religious marriage without civil marriage (p<0.001), extended family (p=0.086), monthly household income of less than US$560 (p=0.018), woman’s low education level (p=0.176), husband’s low education level (p=0.012), woman’s employment status (p=0.094), husband’s employment status (p=0.019), age at first marriage (p=0.072) and age at first pregnancy (p=0.031) increased unmet need. In the multivariate analysis, the only significant variable was religious marriage without civil marriage (odds ratio 4.96, p=0.011) (Table 5).

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants

Table 2: Reproductive characteristics of study participants

Table 3: Percentage distribution in the study population of currently married women according to contraceptive need category

Table 4: Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis of determinants of unmet need for family planning in the study population

Table 5: Pooled logistic regression analysis (bivariate and multivariate) of determinants of unmet need for family planning

Figure 1: Criteria for unmet needs for family planning.

Figure 1: Criteria for unmet needs for family planning.

Figure 2: Categories of behaviours displayed by study participants to use a family planning method, and their need for family planning.

Figure 2: Categories of behaviours displayed by study participants to use a family planning method, and their need for family planning.

Discussion

This study was conducted to determine the levels and associated factors of unmet need for family planning in currently married women aged 15–49 years living in two settlements, rural and urban, in Karabuk Province. The study presents remarkable findings regarding the powerful effects of socioeconomic inequalities and social determinants on women’s fertility behaviours. This was observed in two settlements located close to each other: Cumayani village and Emek neighbourhood. The most striking finding of the study was that the strongest determinant of unmet need for family planning was religious marriage without civil marriage.

In this study, the percentage of unmet need for family planning in the women living in Cumayani village (9.7%) was approximately twice that of the women living in Emek neighbourhood (5.4%). In both settlements, level of unmet need for limiting childbirths was higher than level of unmet need for spacing childbirths. According to the TDHS-2013, family planning needs are unmet in 6% of married women between the ages 15 and 49 years in Turkey. The percentage is 3% in western Anatolia and rises to 12% in south-eastern Anatolia. Unmet need in rural areas is 8.4%. Of this percentage, 4.8% represent unmet need for limiting births and 3.6% unmet need for spacing births. In urban areas, these percentages are 5.2%, 2.9% and 2.3% respectively6. In the present study, although the percentage of unmet need in Cumayani village was higher than in Turkey overall and in rural areas, the percentage in Emek was consistent with that in urban areas in Turkey.

In another study conducted in Karabuk Province, unmet need was the same as that in Cumayani22. In Manisa, a province in the western part of Turkey, level of unmet need in women living in the slums (17.7%) was twice that of women living in the city centre (8.3%)19. The levels of unmet need determined in the present study and in other studies conducted in Turkey were lower than the levels determined in studies conducted in other developing countries. In Bradley and Casterline’s study, in Turkey, unmet need in married women aged 15–49 years was 9.5% in 2003. In that study, with the exceptions of Vietnam, Colombia and Peru, Turkey was determined to have the lowest level of unmet need among 60 developing countries23. In Bihar state in India, the level of unmet need, which was 25% overall, was 32% amongst Muslims and 36% in adolescents15. In another study in India, the level of unmet need was 44% in rural areas24. In Nigeria, the rate of unmet need in rural areas (24%) was almost three times that of urban areas (9%)20.

In the present study, a religious marriage without a civil marriage was determined to be the strongest determinant for unmet need. Approximately 1 in 10 rural women and only one urban woman were married by way of only a religious ceremony. Although marrying by way of only a religious ceremony is religiously and socially acceptable in Turkey25, it is prohibited by the Turkish Civil Code26, which also decrees the legal marriage age is 18 years. The Civil Code also states that a religious marriage can be performed only after the civil marriage is fulfilled. The level of religious marriages in Turkey was 15% in 1968, but declined to 12% in 1978, to 8% in 1988, to 7% in 1998 and to 5.8% in 2003. However, it is as high as 8.4% in rural areas and 14.6% in eastern Turkey27. In a study based on the findings of the TDHS-2008, the level of marriages performed both legally and religiously was 93.3%, with 3.3% for only a civil marriage and 3.3% for a religious marriage alone28.

A religious marriage without a civil marriage not only paves the way for child marriages, but it also reduces women’s participation in social life and prevents them from benefiting from public services. These women and their children are faced with many difficulties such as not being able to receive an inheritance or birth certificate, and not being able to enrol in a school. In this respect, religious marriage should be considered as a factor that discredits women and reinforces gender inequality7. The male-dominated traditional norms, in which such marriages are approved, can be debated as reinforcing the barriers to women’s ability to make decisions about their fertility and, in a broader context, as preventing the autonomy of women concerning their own lives and their participation in formal education and joining the workforce.

The strength of the present study is that it concretely demonstrates the relationship between religious marriage without civil marriage (which is an important problem in Turkey) and unmet need. One of the limitations of this study was the small number of individuals in the sample, which included those living in only two settlements. Another limitation was that the data on the subgroups was limited.

Conclusion

The present study showed that the unmet needs for family planning for rural women were double those for urban women. A religious marriage without a civil marriage was the strongest determinant of unmet need. These marriages increased the unmet need by 4.61 times in the analysis comprising rural women, and by 4.96 times in the analysis including both rural and urban women. Significant socioeconomic inequalities were found between the two settlements. The fertility behaviour of rural women was similar to that of women in patriarchal societies. The study results indicate that the elimination of unmet need for family planning will require comprehensive interventions. Although the practice is illegal, the dynamics that cause women to marry only through a religious ceremony should be examined in the context of their causal relationship, including proximal and distal causes. The elimination of social and gender inequalities in society should be taken into account when planning interventions, with the goal of empowering women to make decisions concerning their fertility.

References

You might also be interested in:

2019 - Prevalence of unmet supportive care needs among Indigenous cancer patients across Australia