Introduction

Provincial policies are typically designed to address the needs of the majority through invoking authority. The importance of provincial policy is that it impacts on almost every aspect of Canadian life, either directly or indirectly. This is especially salient among women who are experiencing or have experienced intimate partner violence (IPV) who are accessing or attempting to access health and social services. Intimate partner violence can be understood as a pattern of physical, sexual, and/or emotional violence by an intimate partner within the context of coercive control1. Coercive control is a devastating reality of IPV, as it is through coercive control that women are robbed of their autonomy and partners are able to dominate and inflitrate all aspects of their lives2. It has been estimated that just over one in four Canadian women will experience IPV at some point in their lives3. Provincial policies have a direct impact on the health and social services available to Canadian women who experience IPV, and inequities in the access to these services are apparent depending on where women live4,5. While a critical discourse analysis (CDA) of policies influential to the delivery of women’s shelter services in urban Ontario, Canada, has been published6, there are no such analyses in the context of rural Canada. This is concerning given the prevalence of IPV in Canada and that roughly one fifth of Canadians are living in rural settings (operationalized, ‘a community with a population of less than 30,000 that is greater than 30 minutes away in travel time from a community with a population of more than 30,000’7). Moreover, the prevalence rate of IPV, the number of women living in rural Ontario, and the reality that policy shapes access to health and social services underscore the importance of further examining the impact and interconnectedness of policies concerning health and social services delivery in a rural context.

IPV has a wide variety of negative health and social consequences for women. Physical health outcomes for women include, but are not limited to, bruises, lacerations, fractures, and head injuries8-10. Research has also established a connection between IPV and serious mental health conditions, such as anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress8,11. These health effects, while significant in their own right, pale in comparison to femicide and filicide, with a recent report indicating one woman or girl being killed every 2.5 days in Canada12,13. As a result of the many health implications, women who experience IPV may require the care of a family physician, psychiatrist, dentist, social worker, and/or psychologist, among others14. The power dynamics inherent in healthcare settings are well documented and perpetuated by the structure of health care in terms of the sanctioned hierarchies of dominance and control15,16. These power dynamics are not unique to health services but also permeate social services, such as food banks, domestic violence shelters, social housing, woman abuse helplines, and/or legal aid that women access16-18.

IPV has been associated with staggering personal and societal financial costs. In a report released by the Canadian Department of Justice in 2012, it was estimated that spousal violence cost Canada C$7.4 billion in 200919. This figure was based on a variety of factors, including expenditures related to the criminal justice system (eg police and legal aid) and victims (eg medical attention and lost wages)19. Since women who have experienced IPV are known to require a variety of health and social services14, and because the delivery of these services requires the complex interaction of provincial governments, hospitals, and women’s shelters, it is essential that thorough, women-centered, violence-sensitive policies be enacted and enforced to ensure that services can be delivered to women in the most meaningful way.

In a community-based sample of Canadian women (N=309, including both rural and urban women), Ford-Gilboe et al (2015) examined whether women who had recently left an abusive partner differed from the general population in relation to their rate of health and social service use14. Service usage rates were found to be approximately 2 to 292 times higher than the general population14. This number is staggering but reflects unmet needs of a vulnerable population as well as difficulty in navigating systems that are not designed with women in mind. For example, participants were 8.5 times more likely to attend a walk-in clinic and 20 times more likely to access an emergency department; however, this increased service use was likely masking the true need that these women were 71.6 times more likely to require the care of a psychiatrist14. Furthermore, the authors reported numerous barriers that prevented women from accessing the services they required, meaning that these rates are considered an underrepresentation. Such barriers included an inability to pay for services, being added to a waitlist, lack of access to transportation and/or childcare, and lack of services in their geographical area14.

Many barriers to services stem from insufficient provincial funding and a lack of attention paid to inequities inherent in an urban-centered solution to a problem that is pervasive across all geographies. For example, a 2015 study reported that for women’s shelters to meet the needs of their communities, they often operate more beds than are government funded, through additional fundraising efforts, and have a substantial reliance on community volunteers20. Within these health and social services (including women’s shelters), accessibility barriers are all heavily influenced by policy as policy drives the funding model. Therefore, obtaining an enhanced understanding of how government, women’s shelter, and hospital policies are applied in the rural context is of utmost importance. Such an understanding of how these policies are related may help inform policy change to improve the delivery of care for women who have experienced IPV.

In addition to the numerous barriers to health and social services, the system in which women are trying to access services is fractured and fragmented21. Systems are often reactive rather than proactive, and shelters are oppressed by ‘structural processes evident through lack of resources, insufficient services for women, and layer upon layer of insensitive bureaucracy’ (p. 524)21. This fragmentation of the system and response to IPV can be more problematic for women living in rural contexts22. Edwards (2015) found that those who live in rural areas may experience ‘worse psychosocial and physical health outcomes due to the lack of services in rural locales and difficulty in accessing services that are available; research also demonstrates that IPV services in rural locales are generally less well funded and comprehensive than in urban locales’ (p. 359)22. The literature has identified the following challenges for women who have experienced IPV living in rural areas: (1) less resources in the community, (2) isolation of both a geographic and social nature, and (3) public transportation limitations22. Moreover, Edwards (2015), in a review of the literature, assessed differences among rural, urban, and suburban women in relation to IPV. Although no substantial differences in IPV rates by area type were found, she noted that IPV in the rural context may be more chronic and severe22. In a cross-sectional American study of 1478 women seeking services from a family planning/abortion clinic, Peek-Asa et al. (2011) reported a higher IPV rate among women living in small rural towns (22.5%) than women living in isolated areas (17.5%) and urban areas (15.5%)23. Meanwhile, a lower prevalence rate was noted among women living in large rural towns (13.3%)23. Peek-Asa et al. (2011) reported that, among the women in their study, those living rurally were approximately three times further away from the closest domestic violence services than their urban counterparts23. Considering the detrimental physical and mental health consequences of IPV and associated negative financial outcomes, it is necessary to ensure that government, hospital, and shelter policies take the specific challenges related to rurality into account.

Policy sets the tone and direction for action. As such, critically examining policies to ensure they are working in positive and intended ways, with minimization of unintended negative consequences, is important24. It is important to achieve a better understanding of how provincial policies are translated into the day-to-day operations of women’s shelters and hospitals as well as whether such policies are aligned well with, or are disconnected from, the realities of the lives of women who have experienced IPV in rural areas. The purpose of this CDA was to examine the degree of alignment and incongruence among provincial women’s shelters and hospital policies regarding the delivery of care and access to services for women who have experienced IPV in rural Ontario, Canada. This CDA sought to assess whether the enactment of provincial policy reached the frontline service providers as intended in the rural context. Specifically, in relation to provincial policy, this CDA assessed the Government of Ontario’s (2004) Domestic Violence Action Plan for Ontario (ODVAP)25 as well as a 2012 update report regarding its implementation26. This provincial policy was juxtaposed onto the relevant policy of a women’s shelter in rural Ontario, Canada. Examining such policies in the rural context is essential as those who have experienced IPV in rural areas have different experiences than their urban counterparts27 and, currently, no policy analysis of these documents has been conducted, signaling a gap in the literature that requires addressing.

Methods

Design

This CDA was a case study of one rural community using a critical, feminist, intersectional lens28,29. This CDA sought to not only describe the existing policy reality for women who have experienced IPV in rural settings but also explain the realities based on the structures, mechanisms, and/or forces at play30. The authors seek to make meaning of the social processes and interplay between these processes within the context of assuming that rural values present within communities will undoubtedly affect the realization of policy. The CDA was based on the principle of focusing on dominance and inequities by pressing the social issue of gaps in services provision and policies that are designed with urban populations in mind and flippantly translated to rural populations. This analysis was grounded in the reality of inequities experienced in rural communities in relation to access to and quality of services. The notion of the application of policy to rural settings as a second thought, compared to urban centers, was forefronted within this analysis. The rural community was selected based on three inclusion criteria: (1) rural community in Ontario, Canada; (2) contained a hospital; and (3) contained a women’s shelter. Rural community was conceptualized according to the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care’s (2010) definition: ‘'rural' communities in Ontario are those with a population of less than 30,000 that are greater than 30 minutes away in travel time from a community with a population of more than 30,000’ (p. 8)7. Hospitals were considered for inclusion if the physical structures were located within the community. Ultimately, many communities met the criteria for this research project. To enhance feasibility of accessing required documents the research team approached a rural community where an existing collaboration was in place with key stakeholders, to allow the researchers to have an in-depth understanding of the community.

Data

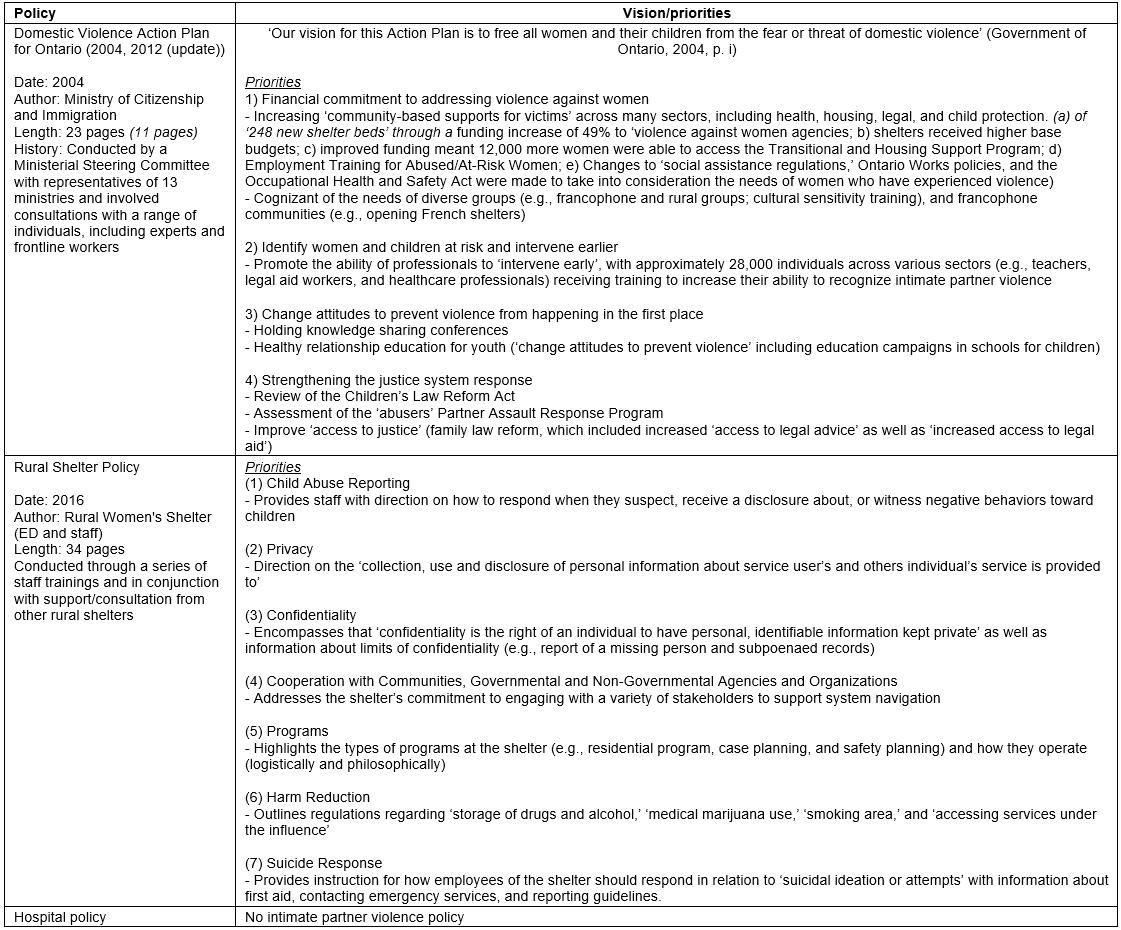

The policies were retrieved from public websites or by contacting general information mailboxes and requesting policies that were in the public domain. Three policies were sought: (1) ODVAP25, (2) the rural women’s shelter policy, and (3) the hospital policy. The ODVAP25 and an update report26 as well as the shelter policy were available within the public domain. The provincial policies were publicly available on the internet25,26. The ODVAP and update were analyzed together, as interpretation of the ODVAP update relies on an understanding of the initial ODVAP report. Meanwhile, the shelter policies were made available by a shelter employee who confirmed that the policies were in the public domain and available to anyone upon request. The women’s shelter is located in rural south-western Ontario and offers a variety of services for women who have experienced violence, including emergency shelter, advocacy, and counseling. Initially, the research team intended to assess the relationships among three levels of policy; however, the hospital located in the area of the women’s shelter did not have any policies specifically addressing the care of women who have experienced IPV. Through communication with a professional standards officer at the rural hospital, the research team was informed that the only possibly relevant policy was on sexual assault, specifically with respect to the transfer of sexual assault evidence. Given that this did not align with the purpose of this analysis, this policy was not included in the CDA. A summary of each of these policies is provided in Appendix 1.

Analysis

This analysis was conducted between January and March 2018 using NVivo v11.4.1 (QSR International; https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo/what-is-nvivo). After the policies were accessed, the research team, consisting of two trained research assistants (EJW and AT) and two principal investigators (TM and KTJ), independently conducted the analysis. Given the reality that IPV affects every aspect of a woman’s life and that the policies are situated in different sectors resulting in diverging orientations, the research team was purposefully composed of individuals from distinct backgrounds; specifically, primary health care (EJW), women’s health (KTJ), legal (AT), and community-based health promotion/expertise in IPV and rurality (TM). First, the research team became immersed in the policy documents by reading them several times to ensure a thorough understanding31. According to Morrow (2005), immersion involves ‘repeated readings of transcripts, listening to tapes, and review of field notes and other data. These repeated forays into the data ultimately lead the investigator to a deep understanding of all that comprises the data corpus (body of data) and how its parts interrelate’ (p. 256)32. Next, a CDA was conducted using a framework established by Fairclough (1995)33, and findings were organized into the following nodes: (1) problems (the issue that the policy was designed to address), (2) obstacles (barriers within the policy), (3) function of the problems (why the problems exist), (4) ways past the obstacles (solutions or plans/actions that are presented/the way forward), and (5) reflection of the analysis (from the perspective of the researcher)33. A CDA is an appraisal of the relationships between documents and the interaction with social practices33. A feature of CDA, according to Fairclough, is that it allows for the inclusion of context within the analysis and focuses on the relationship between the policies and social practices33. During the immersion and coding processes, there was constant movement between immersion, coding, categorization, and creation of meaning within the themes. The researchers vacillated between stages during the independent coding in the analysis process as discoveries were made until the researchers were satisfied that all data were integrated into codes and all codes were complete34. The team used both open and axial coding. Open coding was undertaken in relation to the analysis categories for each policy34,35. Axial coding was used to underscore the gaps and overlap both within and between policies36. When necessary, subnodes and mother nodes were used. These analyses were undertaken by TM, EJW, and AT. Meanwhile, KTJ did not initially complete the analysis; however, she became immersed in the data and instead acted as an impartial new perspective to address discrepancies in coding amongst the research team37. After individual coding was complete, the research team met to discuss themes; consensus was reached. During the meeting, both TM and KTJ recorded themes. Next, they wrote a synopsis, which was then circulated among research team members to ensure the recorded findings accurately encompassed the consensus from the group discussion. Refinements were made until all members agreed the findings were reflective of the discussion.

Ethics approval

The primary author (TM) discussed the undertaking of this policy analysis with the University of Western Ontario research ethics board. Since this was an analysis of publicly available documents, ethics approval was not required.

Results

The results of this critical policy analysis are presented in two separate sections, each using Fairclough’s (1995) framework33. First, an individual analysis of each policy is discussed. Subsequently, findings from the analysis of how the policies interact and gaps among policies are presented.

Individual analysis of policies

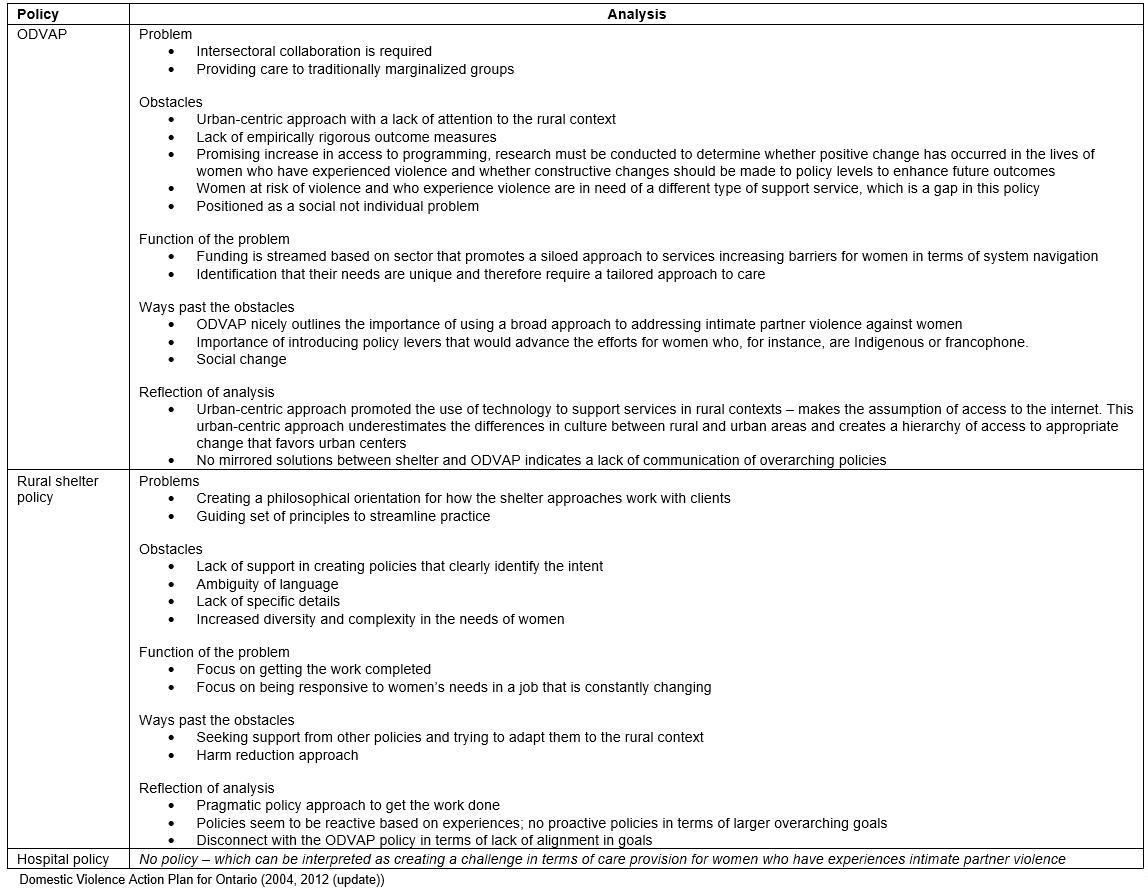

Overall, these policies appeared well-intentioned, containing valuable and meaningful strategies to address issues related to providing services for women who have experienced IPV. For example, the ODVAP (2004) included the following strategies: ‘Expert training advisory panels will develop and/or promote core training materials for front-line workers, professionals, neighbours, friends and families to help them detect the early signs of abuse’ (p. 11), and ‘Funding … will be provided for a new pilot training program to help abused women succeed in the workforce and gain economic independence’ (p. 8). However, as with any complex issue requiring the collaboration of various sectors and policy domains, there are challenges yet to be overcome. These challenges, for each policy, are presented using Fairclough’s (1995)33 framework in Table 1.

Table 1: Internal analysis of intimate partner violence policies using Fairclough’s critical discourse analysis framework

Interaction of policies

Policies do not exist in isolation; rather, they are required to interact with one another, both in terms of populations they serve and achieving the broader social goal. In thinking about how these policies interact or intersect and how the policies provide context for one another, the following main findings arose: (1) problems: missing link; (2) obstacles: ambiguity in perspective, disconnectedness in training goals, affirmative action required, and lack of hospital policy; (3) function of the problem: working in silos; and (4) ways past the problem: hospital policy – a starting place.

Problems: missing link

A missing link or gap in terms of how the ODVAP and the rural shelter policy would actually work together toward a common goal was apparent. The missing link was a problem underscored in both policies: given the complexity of IPV, the ODVAP25 focused on the need for societal change, which therefore involved all sectors. They stated a need to have ‘broad-based interventions through a wide range of sectors (health care, education, justice, business, unions, faith groups, etc.)’ (p. 2) as opposed to ‘a reactive, fragmented approach’ (p. 2). Meanwhile, the shelter had a specific policy on how to work with other agencies, with valuing of cooperation across sectors. This was a possible indicator of readiness for change, both on the part of the government and the women’s shelter, and the realization that the traditional siloed approach to care/service delivery is insufficient. Despite the good intentions of integration, the siloed approach to care that exists represents a significant power relationship in that it is up to the women to navigate complex systems that are not designed to work in tandem. Moreover, this siloed approach to care is perpetuated by current funding models, which do not prioritize or support integration at a service level. Specificity was another main gap in relation to defining how to achieve societal change and integration in terms of specific tangible solutions, such as ways for the policies to interact that would be appropriate for rural settings.

Obstacles: ambiguity in perspective

Each of the policies presented the problem from a different perspective, and this led to a degree of ambiguity. For example, provincial policy had the intent of bringing about society-level change in terms of education and rates of IPV across Ontario. The ODVAP stated that ‘a high profile public education campaign is targeting boys and girls aged eight to 14 years, and the adults who influence them. Pre- and early adolescence has been identified as a crucial time for the emergence of patterns of violence and victimization’ (p. 12). The focus here was largely to tackle change through a social determinants of health approach in dealing with violence in the Ontarian policy25. Conversely, the shelter had the intent of bringing about change at an individual level. Specifically, for clients who have experienced IPV and are using services, the shelter had the intent of supporting women in navigating systems through compassion, a trauma and violence-centered approach to care, and a harm reduction lens. However, what was missing in terms of linking these policies was a connection related to how societal change would be achieved when the organizations doing frontline work are only interacting with individuals who have experienced violence who have reached out for help.

Obstacles: disconnectedness in training goals

Both policies focused on the need for training. In the ODVAP, the government committed to training individuals to identify IPV25, that is, ‘enhanced training in the health, education, justice and social services sectors for front-line professionals and service providers as well as neighbours, friends and families across Ontario to recognize the signs of domestic violence and to help abused women get the support they need’ (p. 3). Meanwhile, the shelter policy involved ongoing, continued training, recognizing that there were gaps in their understanding and a need to stay up to date. However, in relation to the ODVAP, follow-through was missing regarding specific direction for how this should or could be achieved for the rural women’s shelter, as well as a plan to support the additional training of frontline service providers25. The lack of training being identified as a gap is an easy way for policies to deflect obstacles to the user of the policy; however, without sufficient direction regarding training goals, users are left with limited direction when attempting to enact policy.

Obstacles: affirmative action required

Another obstacle in both the government25 and rural women’s shelter policy was that for some aspects of the policy to be enacted there was a need for affirmative action. Both policies, at times, required women to self-identify as having experienced violence prior to the policy being able to respond to their needs. Policy that engages women who have not identified as being in an abusive relationship or who are in an abusive relationship but are not yet ready to leave the relationship are lacking. Given the affirmative action required, specifically, leaving the abusive partner or identifying the relationship as abusive, this limited the scope of the policies to a very specific segment of the population, thereby marginalizing a large subset of women. Ultimately, the ODVAP25 and women’s shelter policies were designed with the intent to promote the use of health and social services for women who have experienced violence, both of which had visions that extended beyond women who have left abusive partners; however the reality is that this model lacks the linkages between policies to support women to access services.

Obstacles: absence of hospital policy

The absence of hospital policy related to providing services to women who have experienced IPV is a cause for concern and may partially explain the disconnect between the provincial government policy and women’s shelter policy. This may suggest that addressing violence against women was not a priority for hospitals and/or that there was a lack of knowledge/training as to how to help women who have experienced violence. This also leaves a gap in services. Without a policy in place, hospitals are not positioned well to respond to the needs of women who have experienced IPV, as there is no continuity in the interaction among healthcare professionals. As such, when women’s shelters advocate the access of healthcare services, the experience for the women who have experienced IPV then largely depends on the individual health care professional with no consistency across providers. Without consistency, which could be governed through policy, there is no guarantee the response accounts for the health and social consequences of IPV.

Function of the problem: working in silos

Essentially, the function of the problem is maintaining the status quo or, more specifically, the siloed approach to care. Specifically, the missing link, ambiguity in perspective, disconnectedness in training goals, affirmative action required, and absence of hospital policy, when considered collectively, pointed to the ultimate disconnect within the system. The two policies (ODVAP25, rural women’s shelter) and the absence of a hospital policy demonstrate that each entity works separately to enact their own agendas without full consideration of the goals of other systems, suggesting a lack of unity and communication.

Ways past the problem: hospital policy – a starting place

When considering the problems, obstacles, and function of the problem, a hospital policy could offer a bridge between the ODVAP25 and the rural women’s shelter in many places. With the ODVAP’s integrated societal change goal25 and the rural women’s shelter’s woman-centered approach to care and system navigation support goal, a hospital policy would be well positioned to bridge these goals within the context of health. Specifically, a community hospital hosts both health and some social services for the general population (ie counseling), which positions them to be an access point for the population for information about the health and social consequences of IPV. A community hospital also provides care to women and families who are experiencing or have experienced acute and chronic conditions associated with violence, which cannot be achieved appropriately without an understanding of the link between health and violence. Although some of this positive work may be happening without a dedicated policy, a policy would help to better serve those who have traditionally ‘fallen through the cracks’. Without a hospital policy on IPV, there is a gap in the alignment of the provincial and women’s shelter policies, which creates barriers to accessing services and the delivery of care for women who have experienced IPV.

Discussion

The disparities among the policies examined in this analysis in conjunction with the absence of hospital policy make the integration of health and social services difficult. Through a CDA guided by Fairclough’s (1995)33 framework, provincial policy25,26 and a rural women’s shelter policy were assessed for congruencies and disparities. For the provincial and rural women’s shelter policies, the divergent overarching aims, lack of clear training goals, and requirement of affirmative action for the policy to respond were all barriers to the policies working together to achieve the broader goal of societal change and/or supporting families to thrive. These barriers presented reify existing power dynamics by taking a hands-off approach to the solution, placing the onus on women and individuals working within the system to change the structure of the system – an unrealistic goal.

The findings of this policy analysis were limited by several factors. First, the findings in this article are based on one rural community in Ontario, Canada, which may or may not be representative of other rural communities, international communities in particular. Second, the analysis was limited by the unavailability of a formal hospital policy. It is likely that actions are being taken within the hospital to address the impact of IPV on health; however, without a unified goal/direction in terms of an overarching policy, the perspective of a hospital was not included in this analysis. Although policy at the provincial level may be set with the best of intentions, it is important to ensure that future policy is carefully evaluated to ensure that targets are met, including those that affect rural areas. Despite these limitations, this critical policy analysis is the first of its kind in terms of examining the alignment of policies supporting health and social services in a rural community in relation to IPV. Future policy analyses should also be conducted to examine systems of text, talk, and action located in social spaces, which would be a logical next step to this analysis.

Additionally, a concerted effort is needed to encourage hospitals to establish formal, unified policies related to caring for women who have experienced IPV. Similar issues have been identified internationally, with a lack of policy present that extends beyond the IPV screening debate38,39. Instead, there is a need to focus on establishing and accounting for the impact of violence on health internationally. Recently, an online safety planning protocol has been implemented in several countries (ie Canada (iCAN Plan 4 Safety)40, USA (IRIS)41, New Zealand (isafe)42, and Australia (I-DECIDE)43). Beyond the safety planning protocol, this series of interconnected programs helps women identify the health consequences of violence and account for them when attempting to leave or more safely stay in an abusive relationship. Inherent in this model is a trauma- and violence-informed care (TVIC) approach – an approach that is commonly used in women’s shelters. TVIC is grounded in trauma-informed care (TIC), which aims to construct care practices that are built on comprehending effects of trauma in terms of health and behavior44. TVIC takes a client-centered life-course perspective on understanding the cumulative impacts of personal experiences on health/wellness. Where TVIC extends TIC is that the approach also integrates the impact of interpersonal and systemic violence as well as structural inequities on individuals’ health44,45. Essentially, TVIC recognizes that past and present experiences of trauma and violence have immediate and ongoing implications for health46. TVIC is a viable solution as it has been shown to take no additional time or resources (beyond initial training) to implement into healthcare settings, and the benefits are widespread, improving care for those with or without histories of violence. While TVIC has excellent uptake in rural women’s shelters, encourage uptake among federal policy and hospitals is equally important, as not only are there resources to undertake such a significant training and paradigm re-orientation, but the impact would be profound not only for women who have experienced IPV but for anyone who has experienced trauma47-49.

To support rural women’s shelters in their goal of helping women and families thrive, it is imperative to underscore the importance of service integration. Service integration is a goal of many federal level agencies; however, there is a significant lack of motivation in provincial policymakers to provide sufficient resources to bring this to fruition. Faced with this reality, rural women’s shelters have been found to work around ineffective systems or gaps in systems to provide care. In a study by Mantler and Wolfe (2018), it was found that a rural community lacked an appropriate response for mental health needs which is echoed in the international context50. As such, rural women’s shelters around the world are stretching their mandate to provide services and connect women with other services to address their needs51, such as in a study of integration between a women’s shelter with mental health services using tele-conferencing technology in the USA50. This ingenuity on the part of rural women’s shelters is not an isolated event. In a recent study of five rural Ontario women’s shelters, innovation in service delivery was explored and it was found that rural women’s shelters use strategies such as community education, networking, leveraging technology, and recruiting resourceful, able leaders in a hub configuration, which involves the integration of services in a localized access point (CENTRAL Hub Model) to improve service delivery for women who have experienced IPV52.

Despite this novel work around gaps within the system, more sustainable solutions are required to support the societal change where ‘to free all women and their children from the fear or threat of domestic violence’ (p. i)25 is the goal. Specifically, the need for system-level integration is imperative as this may reduce the gap between provincial and women’s shelter policies, while also dealing with issues related to limited access for women to healthcare services. In a review by Mantler et al (2018)53, they examined the only four studies around the world where primary healthcare services were integrated in women’s shelters, which were all from the USA50,53-56. In these studies, a variety of primary healthcare services were provided by an array of practitioners, and they included dental procedures54, primary care from a nurse practitioner55, rapid HIV testing as well as education56, and teleconference psychiatry facilitated by nurse practitioners50. Providing women with these services at shelters was associated with several positive outcomes, such as increased access and acceptability, bridging individuals to their healthcare needs, and decreasing future healthcare burden53. In another example, Attala and Warmington (1996) reported that when nurse practitioners (NP) provided care to women and their children at a shelter-based clinic, women most often rated the services positively for themselves (n=69; 95.5%) and their children (n=95; 96.7%)55. Meanwhile, services provided by a nurse practitioner under the direction of a remote psychiatrist (via teleconference) helped lead to a decrease in mental health-related emergency room visits50. Although more research in this area is necessary, especially in the Canadian context, these findings showed the important and promising role advanced practice nurses (such as nurse practitioners) can play in promoting the wellbeing of women who have experienced IPV53.

Conclusions

Integrated systems are paramount for women who have experienced IPV. These women face inherent barriers stemming from power relations in health and social services use, including barriers to accessing services, the decision to disclose or not, and the compounding effects of health, social, and economic consequences of violence on their lives14. Given the turmoil in the lives of women who have experienced or are experiencing violence, it is imperative that systems respond appropriately. The gaps between policies (and lack of policy) charge policymakers and administrators with the responsibility to ensure that policies are attentive to the needs of those who have experienced IPV. Furthermore, researchers who study IPV should ensure that policies created are based on the best possible evidence and that they are implemented in ways that effect tangible positive change in women’s lives. Lastly, frontline service providers need to ensure policies are being implemented in ways that reflect the intent of the policy and are ultimately working to improve service delivery. Despite the gaps found between provincial and rural women’s shelter policies and the need for these issues to be addressed, there are clear options that are empirically grounded to improve services and access for women who have experienced IPV in rural communities, which may be relevant to policymakers worldwide.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contribution of Adrian Taylor to the analysis and interpretation of policies.

References

appendix I:

Appendix I: Summary of policies

You might also be interested in:

2014 - Mount Isa Statement on Quad Bike Safety

2005 - Rural nursing unit managers: education and support for the role