Introduction

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women, and one of the leading causes of mortality in women worldwide1. In 2012, there were 528 000 new cases of cervical cancer around the world; 266 000 of these cases resulted in death1. Cervical cancer screening (CCS) is very effective in reducing the incidence and mortality associated with cervical cancer because it detects abnormalities before they progress to cancer2. As a population-based screening program, CCS is often held as an exemplar of public health universal screening initiatives because it has a high sensitivity and specificity compared to other treatable diseases in North America and Europe3,4. Increased uptake of CCS programs has been correlated with a reduction in the mortality of cervical cancer in Canada5,6 and the USA7. Despite the dissemination of CCS worldwide, there has been little change in incidence and mortality from cervical cancer8,9.

Traditionally, CCS has been performed via Papanicolaou (Pap) smear, a procedure in which cervical cells are physically scraped from the inside of the cervix and observed to detect abnormal growth, which may indicate precancerous tissue that may progress to invasive cervical cancer10. Recently, some jurisdictions have moved towards human papillomavirus (HPV) testing as the primary CCS modality4. The HPV test identifies the presence of a number of strains of HPV known to be precursors of cervical cancer11,12.

There are disparities in cervical cancer incidence in some groups of women, reflecting different rates of participation in and access to CCS13. Rurality, among other demographic characteristics, is a risk factor for higher cervical cancer rates14. For example, in rural Appalachia, USA, the prevalence of cervical cancer is 35% higher than the national average, which may be due to lower CCS participation caused by the lack of access to CCS services15.

Previous literature has found many barriers and facilitators to CCS participation. In a previous systematic review of 117 qualitative studies of women’s preferences and experiences of CCS, the authors identified barriers to participation such as emotional discomfort associated with the screening procedure, relationships with healthcare providers (HCPs), and comfort and inclusion in the healthcare system16. Some of these barriers may be more pronounced for women in rural and remote areas due to increased barriers to accessing healthcare services13,17. Barriers particularly relevant to women in rural areas may include the limited availability of HCPs in their area, the need to travel long distances to receive necessary care, and a rural culture that may inculcate beliefs that seeking care may affect their physical ability to earn a livelihood, thereby discouraging women from participating in CCS18.

For rural women, access is not only a function of financial and physical resources, but also ‘a multidimensional concept that is contextually modulated by the place, the players, and the processes within which it is examined’ (p. 180) 19. Access to healthcare services requires a negotiation between rural HCPs and urban healthcare facilities, the availability of adequate transportation to healthcare facilities, a rural culture that supports and advocates for preventive health, financial capital and insurance status, and patient-centered care (PCC)14,20,21.

Given the unique barriers and facilitators that rural women may face accessing health services, an examination of this issue is worthy of focused attention22-24. Improving access to CCS for women in rural and remote areas has the potential to prevent cervical cancer; geographical disparities in accessing this important form of screening are an issue of inequity. This systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis aimed to elaborate on the existing qualitative evidence about rural and remote women’s perspectives to CCS participation, with the aim of supporting the design and administration of interventions that improve CCS rates for women living in rural and remote areas of high-income countries. The research question for this investigation was ‘What are the perspectives, preferences and experiences of women who live in rural and remote areas about cervical cancer screening?’

Patient-centered care

The concept of PCC has been prolific in the medical and health science literature. Decades of research have transformed the patient–physician relationship from a primarily paternalistic dynamic to one that acknowledges, values and integrates patient perspectives, preferences and experiences in health care25-27. PCC is often understood for what it is not: not paternalistic, not disease-centered and not technology-centered28. Moreover, PCC may be considered to be an approach that is responsive to a patient’s needs and preferences29, and takes into account the patient’s level of desire for participation in shared decision-making30. PCC emphasizes a need to address patients’ biopsychosocial preferences alongside their medical needs, to acknowledge that patients are experts in their disease experience, and to adopt a notion of partnership between HCPs and patients that is exemplified by models of shared decision-making28,30,31. These aspects of PCC may improve women’s experiences of the healthcare system and their relationships with HCPs32.

Although there is no shortage of research describing PCC, there is relatively little application of these concepts to interventions designed to improve women’s health. Research in this area has identified a strong need to tailor PCC concepts in a way that reduces gender inequities by enhancing the rapport between patients and care providers and improving patient compliance in treatments33. Furthermore, for rural women, there is an additional complexity related to inadequate access to high-quality care in rural and remote areas; this has been recognized in calls for research and the design of interventions to alleviate inequities in health outcomes related to the intersections between gender and geography34. For the purposes of this research, the concept of PCC was used to anchor the challenges rural women face seeking CCS to the ones most aligned with interactions between women and their HCPs. The findings of the present analysis are presented with a PCC lens, and implications of these findings with the broader literature on PCC are highlighted in the discussion.

Methods

This systematic review represents a secondary analysis of a subset of data retrieved as part of a larger systematic review conducted under a contract with the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH)16. The initial systematic review was conducted in collaboration with CADTH, as part of a health technology assessment of HPV testing for the purpose of cervical cancer prevention16. In the initial review, the authors synthesized 117 qualitative research studies about women’s experiences and perspectives of CCS without placing any restriction on geographic area or demographic features of women. The present review focuses on a subset of this large dataset, studies that concern the experiences and perspectives of women living in rural and remote areas.

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in Ovid Medline, Ovid Embase, Ovid PsycINFO, EBSCO Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PubMed and the Social Sciences and Humanities segments in Scopus. Selected grey literature sources identified from the Grey matters checklist were also searched35.

The search was limited to studies published since 1 January 2002 to capture recent literature relevant to women’s experiences with CCS in rural and remote areas. The search was conducted on 6 February 2017, with monthly search updates ensuring that the review was current to 1 June 2018. Results were limited to English- and French-language publications. Conference abstracts were excluded from the search results.

The search terms combined a topic-specific search filter about CCS with a published search filter designed to retrieve qualitative research36. The CCS search terms were developed, and peer-reviewed by information scientists according to the PRESS criteria37. This review searched within the 117 eligible studies included in the initial review to identify studies conducted in rural and remote areas in high-resource countries. The definitions of ‘rural’ and ‘remote’ provided by Statistics Canada and OECD were used, including studies of women who lived in small towns and villages with less than 1000 inhabitants or a population density between 150 and 400 persons/km238. There are notable differences between rural and remote areas. However, these distinctions were not discernable in the studies reviewed. As a result, the authors thought it was more appropriate to review the studies from rural and remote areas together, while recognizing that there may be differences in the preferences and experiences of women between these areas. Two authors screened the titles and abstracts of studies retrieved from the literature search. If consensus was not reached, then the full text of the study was reviewed for eligibility and discussed amongst three authors.

Eligibility criteria

The authors included studies that were published between 1 January 2002 and 1 June 2018. Eligible publications were primary, empirical qualitative research that used any form of descriptive or interpretive qualitative methodology. These publications involved adult women (aged 21–70 years) with data relevant to any aspect of women’s perspectives on CCS in rural and remote areas of high-income countries. The search was restricted to high-income countries to ease the comparison of data across health systems. Studies conducted in Canada, the USA, New Zealand, Australia and members of the European Economic Area were eligible for inclusion. Included studies were published in English and available through the McMaster University library system, interlibrary loan system or correspondence with the primary author.

Qualitative studies that did not include women’s experiences and perspectives relevant to CCS, the perspectives of elderly women (≥71 years), adolescent or pediatric populations and studies that were conducted in areas not considered to be rural or remote according to the Statistics Canada and OECD definitions were excluded. Moreover, this review excluded studies conducted in rural and remote areas of low- and middle-income nations, and studies that were unclear about the participant demographic, the location of the research study, or that did not contain data relevant to the research question. Furthermore, studies that were not published in the English language and those without primary empirical data were excluded. Finally, quantitative research that represented findings using statistical hypothesis testing was excluded from this study.

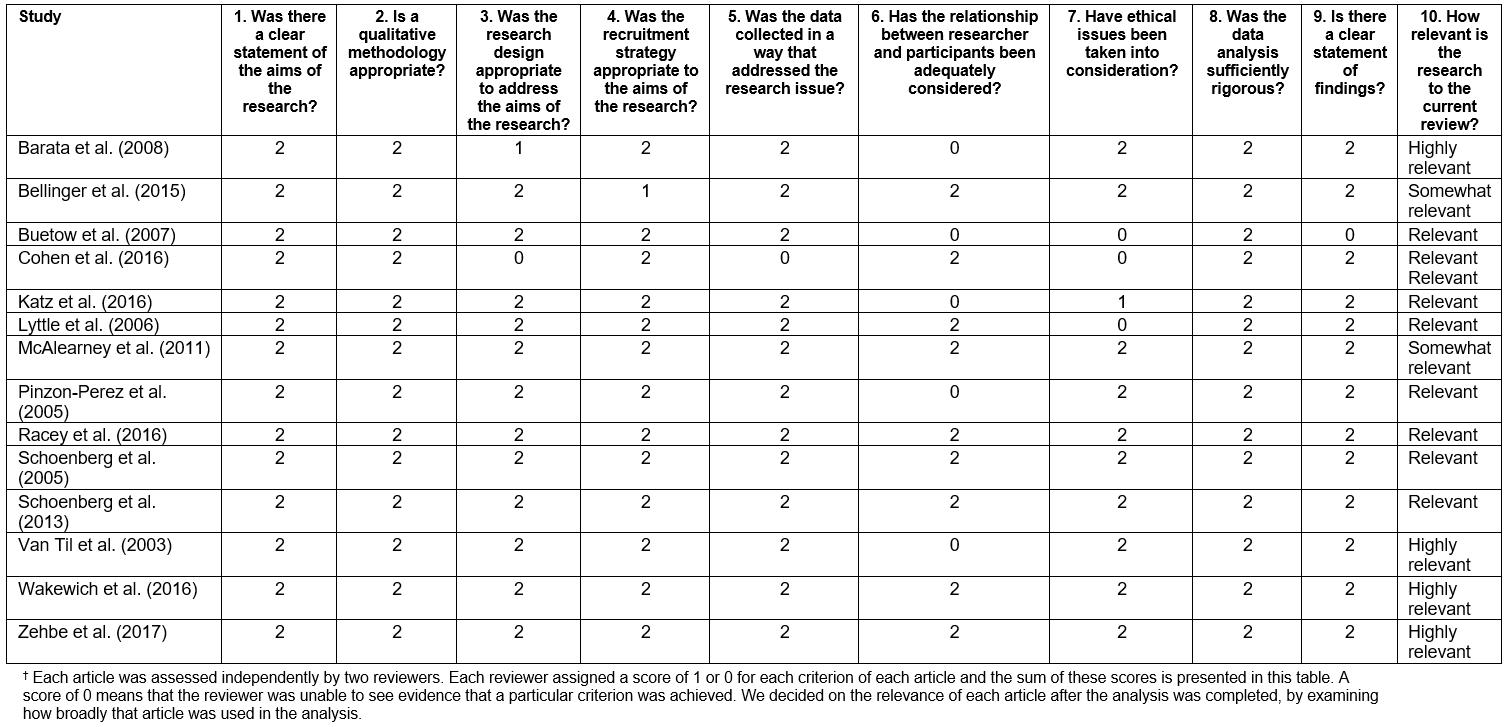

All published qualitative research relevant to the research question was included and there were no limitations on the search based on qualitative methodology or independently assessed quality. Quality appraisal of the studies was performed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Qualitative Checklist39. The results of critical appraisal are presented in Appendix I to inform the evaluation of studies; however, the authors did not use appraisal to exclude studies from this review. This decision comes from an ongoing debate amongst qualitative scholars about the usefulness, appropriateness and approaches to critical appraisal of qualitative research. The authors’ perspectives on this issue are detailed elsewhere40. Studies that contained findings not supported by data were also excluded from this study, consistent with the qualitative meta-synthesis method described in the next section41.

Analytical method

This study employed the integrative technique of qualitative meta-synthesis41. This research approach synthesizes findings from multiple qualitative studies to produce a new interpretation of the phenomenon while retaining the original meaning of each qualitative study. Pre-defined research questions and search strategies were used to guide the collection, eligibility assessment, relevance and data extraction.

The primary source of data was authors’ interpretation and conclusions described in published journal articles. Data presented in the studies were not re-analyzed, rather data were the ‘data-driven and integrated discoveries, judgements, and/or pronouncements researchers offer about the phenomena, events, or cases under investigation’ (p. 903)42.

Two researchers extracted data relevant to the research question, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion with at least three authors. Guided by grounded theory43,44, a staged coding process was employed to break the findings of studies into their key themes and concepts. These components were regrouped thematically across studies. Using inductive41,42 and constant comparison approaches44, the final list of themes was developed in a way that was relevant to the research question, and emphasized the significance, prevalence and coherence of findings across a large number of studies.

Ethics approval

Because this meta-synthesis analyzed studies already in the public domain, approval from an institutional research ethics board was not required.

Results

Search results and summary of included studies

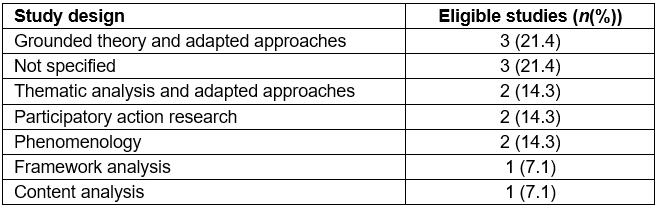

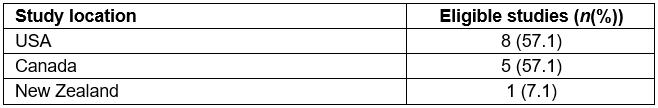

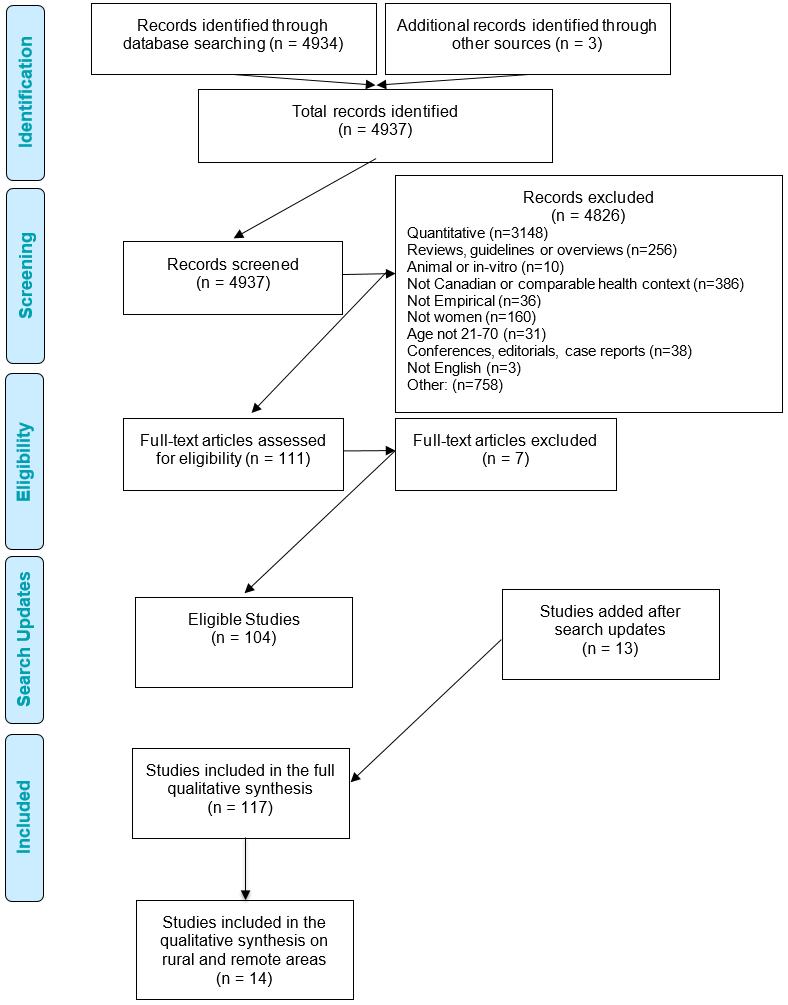

Fourteen studies that examined the perspectives, preferences and experiences of 566 women accessing cervical cancer screening in rural and remote locations were synthesized in this review. These locations include small towns and rural regions (eg rural Appalachia) in the USA, Canada and New Zealand. Figure 1 is a PRISMA diagram of the article screening and selection process. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the number of included studies according to study design and study location.

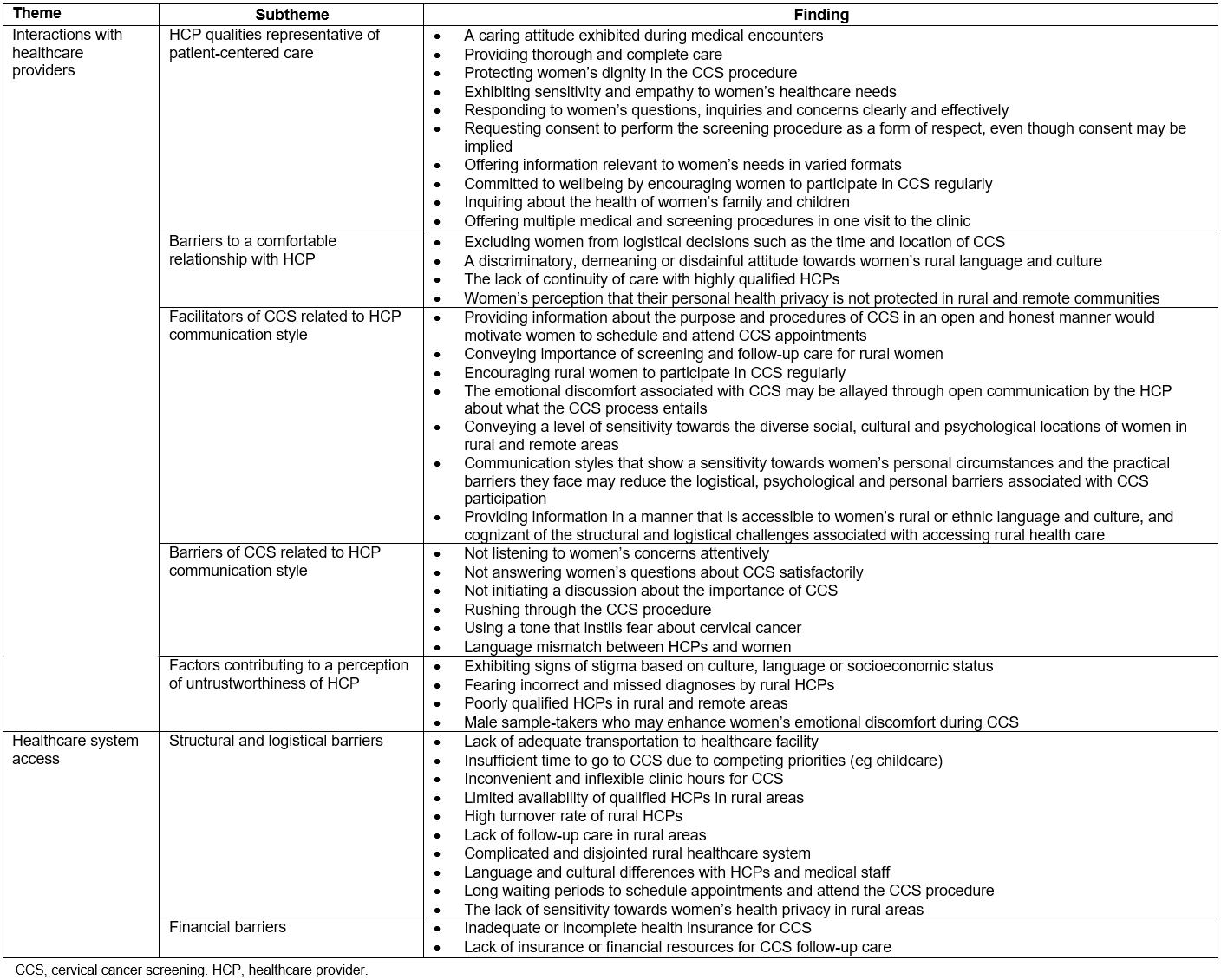

In this synthesis, the findings are separated into two distinct themes: interactions with HCPs and healthcare system access. Data relevant to these themes are overlapping and, in some cases, interdependent. The results section details these two themes separately, followed by an integrated discussion about the implications of these themes to CCS in rural and remote locations in high-resource nations. In this section, factors that are both relevant to and distinct from rural location are described. These factors are summarized in Table 3.

Table 1: Body of evidence examined according to study design

Table 2: Body of evidence examined according to study location

Table 3: Summary of factors that influence seeking cervical cancer screening

Figure 1: PRISMA diagram of article screening and selection process.

Figure 1: PRISMA diagram of article screening and selection process.

Interactions with healthcare providers

For many women, HCPs were described as individuals who strongly influenced their preferences, experiences, perspectives and expectations of health care. Rural women described many factors that influenced their relationship with HCPs. Three subthemes emerged: PCC approach to health care, receiving medical information in a manner that is cognizant of rural women’s circumstances and the factors that contribute to women’s mistrust of HCPs and the healthcare system.

Facilitators and barriers to a comfortable rapport with HCPs: Women in most studies described their experiences with CCS as dependent on whether they had a comfortable rapport with their HCP45-54. Although multiple barriers were mentioned by women to cultivating a comfortable rapport with their HCP, these barriers appear to be mitigated or reduced by a PCC approach to health care. Moreover, for many rural women, PCC was such an important factor in CCS that its absence was expressed as an obstacle to maintaining a comfortable rapport with their HCP47,48,52,53. The focus here is on relational aspects particularly relevant to rural and remote women, with more general findings summarized in Table 1.

The concepts and ideas of PCC were recurrent in women’s discussion about their preferences, expectations and experiences of CCS in rural and remote areas45-54. Barriers to PCC specific to rural patient–physician relationships include determining the time and location of CCS without considering the logistical obstacles that rural women may face or including women in the decision-making process46,53; having a discriminatory, demeaning or disdainful attitude towards women due to their distinct language and rural culture42,43,47,50; the absence of continuity of care with HCPs who may practice in rural areas on locums or for only short periods48,52-54; and women’s perception that their personal health privacy in rural and remote locations is limited due to the close-knit nature of rural communities49,52. In particular, Racey and Gesink described that rural women’s perception of limited privacy comes from limited social distance with HCPs and medical staff in rural and remote areas49. The limitations of social distance extended to worries about whether test results conveyed by phone were audible to other patients in the waiting room of the test facility, who might know the patient given the nature of small communities53,54.

Generally, rural women preferred to receive medical information in a manner that is accessible to their language and culture and cognizant of the structural and logistical challenges to accessing CCS in rural and remote locations45,46,51. In this case, accessibility may refer to HCPs’ ability and willingness to appropriately convey the importance of screening and follow-up care55, encourage and remind rural women to attend CCS regularly47,49-52 and convey a level of sensitivity towards the diverse social, cultural and psychological locations of women in rural and remote areas48,50,52,54. Effective communication that shows a deliberate sensitivity towards women’s personal circumstances and the practical barriers they encounter due to rural residence may reduce some of the logistical, psychological and personal barriers associated with CCS participation46,48,52,56. For example, Black women in rural areas in one study emphasized the importance of their HCPs being sensitive to the costs of screening and follow-up care45. Moreover, some women also explicated a strong preference for their medical clinic and HCP to offer several medical and screening procedures in one visit51. This preference for ‘bundling’ medical procedures arose from a desire to overcome obstacles specific to needing to travel to the clinic over several days, which was detrimental to women’s work and family priorities51.

Inadequate communication from HCPs may increase women’s emotional discomfort during the screening procedure related to uncertainty about the purpose and process of CCS45,47-52,55. For many women, inadequate communication comprised being cared by a HCP who did not listen to their concerns45,47, rushing through the CCS procedure35, not answering the questions posed by women about CCS satisfactorily47,51, not initiating a discussion about the need and importance of CCS for women residing in rural and remote areas55 and using a tone that instilled fear of death about cervical cancer in women51. Pinzon-Perez and associates found that a language mismatch between HCPs and rural Latina women may decrease CCS participation48. The use of language that is accessible to women and aligned with their social location in their own rural community was a cited preference among several women45,51. Pinzon-Perez et al found that the majority of rural Latina women they interviewed sought a HCP who could speak their native language, a preference that is harder to meet in rural areas for those who speak minority languages48. Black and Latina women in two studies indicated a desire for information that was relevant to their unique needs45,48.

A supportive relationship with HCPs creates an environment of comfort for women and exemplifies a patient-centered approach to health care. Such a relationship may encourage women to initiate and continue CCS despite the many structural and logistical barriers they encounter when accessing the healthcare system.

Trust and mistrust of healthcare providers: Issues around trust and mistrust were a recurrent theme in women’s discussions about their interactions with HCPs in rural and remote areas45-56 (Table 1). Although most women considered their HCPs to be trustworthy, a sizeable group expressed distrust47-53,56. For rural women, distrust in clinicians may arise when HCPs show signs of stigma towards those of a lower socioeconomic status, participate in free insurance programs and reside in rural locations50,51,53,56. This obstacle may emerge from concerns about how rural HCPs interact with women and a fear that HCPs will show contempt and chastise women about their unhealthy habits50. Moreover, due to an inherent mistrust in the healthcare system, rural women may have emphasized a tenacious fear of incorrect or missed diagnoses that may result in adverse consequences to their health and lifestyles47,53.

Rural women’s fears and mistrust of their HCPs may arise from an underlying perception that HCPs in rural and remote areas, compared to those in urban areas, are poorly qualified to practice medicine. Some rural women viewed their HCPs as not being sufficiently competent or having ambiguous qualifications, amplifying their mistrust of HCPs47,50,51. McAlearney et al found that many women expressed skepticism and distrust in their HCP’s qualifications, certifications and training: ‘Participants questioned if local doctors were truly physicians and were even skeptical of the degrees and certificates posted in offices’ (p. 124)47.

Healthcare system access

Women identified many structural and logistical barriers to healthcare system access45,47,48. These included lack of adequate transportation to the healthcare facility where they would receive CCS50,51,54,56, insufficient time to attend appointments due to competing priorities such as childcare and work50-52,54-57, and the inconvenient and inflexible hours of many healthcare facilities providing CCS49,50,52,54.

Women also described limited availability of qualified HCPs in their rural location50,52, and the HCPs that were available were not taking new patients52. Some had concerns about limited access to follow-up care in their rural community in the event of a positive finding from a CCS screening test52,53,56,58.

Discussion

Review of findings

This qualitative meta-synthesis described the perspectives and experiences of rural women concerning preferences and access to cervical cancer screening. Findings from 14 studies were organized in two themes; the first described elements of access to CCS related to interactions with HCPs. HCP interactions may serve as barriers or facilitators to CCS, depending on the HCP’s characteristics and patient-centered qualities. The second theme identified rural women’s struggles accessing healthcare facilities. Women described challenges related to logistical and structural access including transportation difficulties, navigating through complex healthcare systems and dealing with the lack of availability of HCPs who provide high-quality and continuous care.

This section described how PCC contributes to the collective understanding of rural health care. This section also illustrates how PCC may be tailored to women’s health issues while being sensitive to both gender and rurality, and the intersections between these two social identities.

Intersection of gender and rurality

The intersection between gender and rurality offers an important opportunity to examine how two different identities may come together to amplify the barriers to accessing CCS59. Examining the ways that gender and rural identities contradict and support participation in CCS enables an understanding of the ways in which issues of interaction, agency and resistance influence rural women’s experiences with CCS.

In the context of CCS, socially constructed norms of gender privacy contribute to the potential for emotional discomfort and embarrassment experienced by some women if cervical cell samples are obtained by a male clinician. Rurality may amplify these important experiences; in small communities there are often fewer opportunities to receive care from a sample-taker of the woman’s preferred gender, who speaks her language and respects her culture, or one with whom she has a comfortable social distance.

The intersection of female and rural identities may intensify the disincentives women experience when accessing CCS. For example, a woman may regularly participate in CCS because the physical pain and emotional discomfort she experiences is allayed by her HCP, who uses communication techniques to establish a comfortable relationship (gender). However, this effort to reduce the barriers to CCS may be futile if she perceives a lack of access to follow-up care in the event that CCS shows a positive result (rurality). In another situation, a different woman may not seek CCS in the first place if she experiences discrimination from her HCP (rurality, gender, race, class, language). However, these concerns may be managed with increased access and availability to alternative HCPs who are perceived by the woman as having the capacity to relate to her situation and appreciate the various factors that complicate CCS participation (gender, race, class, language).

The concept of rural idyll, which romanticizes the perceptions of rural life as happy and prosperous, elaborates an additional dimension to the discussion of intersectionality between gender and rurality60. The rural idyll may be critical to explaining how the normative roles of rural communities that categorize females as individuals with certain knowledge, attitudes and behaviors may circumscribe the extent to which and how they seek CCS. For example, Little described how the rural idyll notion emphasizes women’s subordinate positions in rural communities, which may be more likely to restrict their roles to domestic roles, further amplifying the structural and functional barriers they face61,62. For example, some rural women may believe their health needs are less important than the social needs of their family 63. This belief, in turn, may discourage women to participate in CCS when these needs conflict, especially given the pervasive logistical and structural barriers to accessing CCS. In this way, subordination may increase the adverse effects associated with the intersection between gender and rurality.

These examples indicate an interdependency between gender and rurality64. The intersection of these two identities may contribute to the magnification of barriers to CCS that further disincentivize women from CCS participation. The relationship between these two identities may be essential to operationalizing how educational interventions may be cognizant to issues of gender, rurality and the interrelations between the two. For example, in a previous review of patient perspectives and experiences not focused on rurality, the authors described eight factors (emotions, cultural and community attitudes and beliefs, understanding personal risk, logistics, multiple roles of women, relationships with HCPs, comfort and inclusion in the healthcare system, and knowledge) that may serve as incentives or disincentives for women participating in CCS16. By using the metaphor of a first-class lever from the physics discipline, the authors conceptualized how the social location of women influences the mechanism through which each of these factors incentivize or disincentivize women’s CCS participation. The authors described how some factors may be more influential for some women, and how certain combinations of factors may serve as strong disincentives to CCS participation for other women16. Concerning rural women, disincentives associated with gender (eg emotional discomfort, competing priorities) are exacerbated by barriers related to rurality (logistics, interactions with HCPs, comfort and inclusion in the healthcare system, and knowledge). In some rural areas there may be a culture or belief that screening is only required when exhibiting overt signs and symptoms of a medical condition or when one’s ability to work is limited significantly49,65. This belief system may influence the relationship, trust and rapport rural HCPs can establish and cultivate with rural women66. Women’s interactions with HCPs and their experiences accessing the healthcare system may be inextricable from a rural culture that imbues a belief system that may oppose preventive health. Effective communication between women and HCPs is crucial to encourage positive CCS behaviors55. However, negative experiences in a ‘culture of referral’ may alienate women who reside in rural and remote areas19, adversely influencing their social and psychological capital, as well as their willingness to seek CCS.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Many research studies have elaborated the barriers and facilitators to CCS for women around the world. However, there is not yet a synthesis of qualitative research of rural women’s experiences in participating in CCS. This study provides a comprehensive synthesis of qualitative evidence about women’s preferences, perspectives and experiences on CCS in rural and remote locations.

Although a high proportion of the studies included (8 of 14) were located in the USA, this review included qualitative data from other healthcare contexts, allowing for a strong consistency across the themes presented in this analysis. Many findings relevant to the two themes presented in this review are congruent with previous literature in CCS and rural or remote health care20,66.

The eligibility criteria for article selection focused on retrieving studies conducted in high-income regions. Therefore, the findings described in this synthesis are likely not transferable to low- or middle-income countries. Studies that met the definition of a rural and remote location by Statistics Canada and OECD were included in this study. A study that was conducted in a location deemed rural and remote under this definition does not mean that its primary focus was to describe the issues pertinent to rural health care and CCS. However, the location was a useful and manageable variable for clarifying the issues pertinent to utilizing and accessing CCS in rural and remote areas.

Conclusions

This article describes the preferences, perspectives and experiences of rural women accessing CCS. By considering how access to CCS may be increased for women living in rural areas, this review casts a spotlight on issues relevant to the interdependencies and interrelations between gender and rurality as social identities. This analysis, alongside the information about women’s perspectives, may contribute to improving the functionality, usability and acceptability of CCS for women residing in rural and remote areas.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contract from the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) for the larger systematic review that made this secondary analysis possible. We appreciate the important contributions made by the CADTH HPV screening team in furthering our understanding of the challenge of offering CCS in a way that is acceptable to women. We acknowledge the research assistance selecting articles and conducting critical appraisal of articles in the larger study from Muzammil Syed, Jacqueline Wilcox, Arjun Patel and Eamon Colvin. We also acknowledge Caitlyn Ford for her peer review of the search strategy and help with the search updates.

MV receives salary support from the Government of Ontario and the Ontario SPOR SUPPORT Unit, which is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Government of Ontario.

References

appendix I:

Appendix A: Results of critical appraisal of studies.

You might also be interested in:

2014 - The right staffing mix for inpatient care in rural multi-purpose service health facilities

2010 - Injections that kill: nosocomial bacteraemia and degedege in Tanzania