Introduction

Rates of scabies and impetigo (skin sores) in remote Aboriginal communities in Australia are amongst the highest in the world1, with prevalences of up to 50% and 70% respectively2. Both skin infections are closely associated, as superficial skin damage from scabies infestation increases the risk of secondary bacterial infection by Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes, the main bacterial pathogens of impetigo3,4. Skin sores also follow minor trauma, abrasions, insect bites and dry skin5 and can result in serious complications1. S. aureus and S. pyogenes can become invasive, leading to skeletal infections and sepsis6,7. Other post-infectious complications include acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis, acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease, reinforcing the global importance of understanding skin infections1,8. Furthermore, a high burden of skin and other infections in early life has been associated with developmental delays and vulnerability in early childhood9. Skin infections were identified as a significant health problem contributing to the high levels of developmental vulnerability identified in Australian Early Development Index survey results for Aboriginal children living in remote communities across the Pilbara in Western Australia in 2007 and 200910. Consultations with parents and stakeholders had attributed skin infections as adversely impacting children’s early development, general wellbeing and school readiness.

Treatment and community control of scabies and skin sores in Australia’s remote Aboriginal communities has proven challenging for decades. Topical permethrin cream for scabies and intramuscular injection of benzathine penicillin G (BPG) for skin sores remain the first-line treatments in these settings11, notwithstanding concerns around compliance for the former12,13. Ivermectin has recently been shown to be superior to topical therapy as an important oral alternative3,14. Recently, short-course oral antibiotics (cotrimoxazole) were confirmed as non-inferior to the BPG injection in treating skin sores15, offering a more acceptable treatment option.

With the availability of newer, evidence based therapies it is important to understand Aboriginal parents/carers’ preferences as well as clinician assumptions about skin infection treatment options and their acceptability within these communities.

Methods

Study setting

The study took place in remote Aboriginal communities and a regional town in the Pilbara region of Western Australia. The traditional Aboriginal people in the region have experienced rapid change in recent decades from a highly mobile, nomadic existence to living in outstations and missions16 and more recently discrete communities where the legacy of colonisation and contemporary social and economic disadvantage are evident in a range of poor health and wellbeing outcomes17.

The populations range from approximately 70 people in the smallest of the four communities to 350 in the largest and 5500 in the nearest regional town18. The distance from the communities to the nearest regional town is 150–700 km. The local Aboriginal Medical Service administers the community clinics and provides outreach services. The clinics in the three smaller communities are staffed by one or two remote area nurses, and two to four nurses and a general practitioner in the larger community. Allied health professionals and medical specialists including a paediatrician visit all four communities regularly. Health services in the town are available through a general practitioner clinic and a small public hospital with emergency services.

Data collection

A series of semi-structured, face-to-face interviews and focus group discussions were conducted using a culturally appropriate yarning methodology19 with parents/carers of young children in the largest community, and healthcare practitioners and service providers servicing all four communities and the regional town. All interviews and focus group discussions were conducted by IAD (female) or DH (male) between October 2014 and November 2015. Interviews and focus group discussions were between 20 and 120 minutes in length. All interviews were recorded and both researchers reviewed their fieldwork observations throughout the study.

RW, an experienced researcher leading the maternal and child health research program in the Pilbara partnership, provided initial introductions and explained the purpose and significance of the skin studies to the larger program of research to all participants. She also provided ethical and cultural guidance to establish relationships with participants prior to the study. Key Aboriginal people and the Aboriginal Medical Service Board also provided Aboriginal guidance.

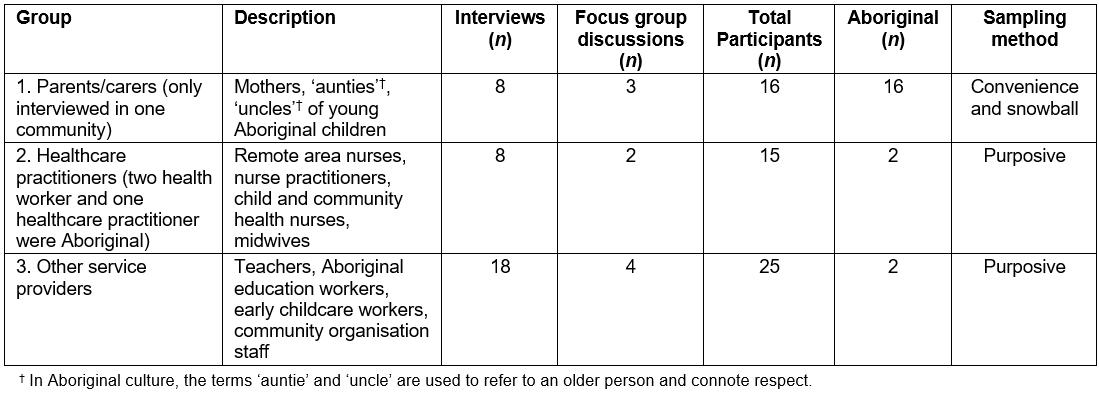

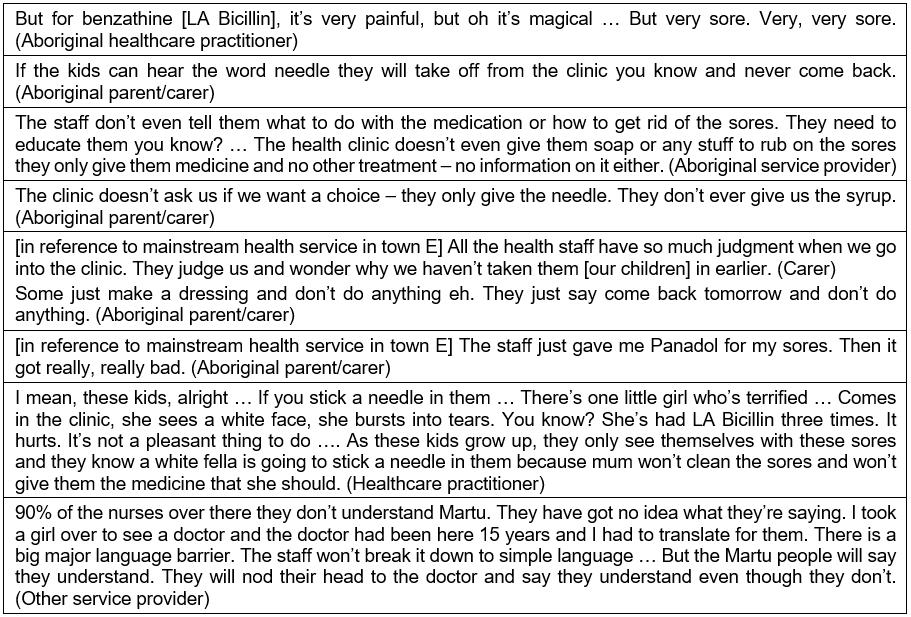

Table 1 summarises data collection activities. Group 1 comprised 15 parents/carers recruited through the community play groups and primary school using a snowballing method to identify additional participants20. Group 2 involved 14 healthcare practitioners and group 3 consisted of 19 service providers involved with parents/carers and their children.

Photographs of scabies and skin sores of varying severities were used to facilitate discussion and obtain insights regarding participant knowledge and understanding of skin infections (Fig1). All participants were provided with information to facilitate (i) greater recognition and knowledge about treatment of skin infections; (ii) perceived child health issues in the community, and their underlying causes; (iii) knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding skin infections; (iv) perceived barriers and enablers to child healthcare provision including skin infections and their treatment (health professionals) and healthcare seeking behaviour (parents/carers) for scabies and impetigo and their perspectives regarding treatment; and (v) specific treatment options for skin infections. Information was collected until no new themes emerged.

Table 1: Summary of data collection activities

Figure 1: Images of skin infections of different severities. These images were shown to participants. in the study to gauge knowledge and understanding of when treatment was indicated. A. Healing impetigo. B. Scabies with secondary bacterial infection evidenced by the presence of papules with honey coloured crusts. C. Purulent impetigo.

Figure 1: Images of skin infections of different severities. These images were shown to participants. in the study to gauge knowledge and understanding of when treatment was indicated. A. Healing impetigo. B. Scabies with secondary bacterial infection evidenced by the presence of papules with honey coloured crusts. C. Purulent impetigo.

Data analysis

Interviews and focus group discussions were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. All transcripts and handwritten notes were imported into QSR NVivo v10 (QSR International; https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo/what-is-nvivo) for data analysis. The transcripts were coded by IAD and DH independently, with formal and informal discussions regarding coding development and emerging findings with one another and RW. Wherever possible, information was checked back with participants. An inductive process was employed, for themes to emerge from the data21. The coding was structured around major topics in the question guide, and additional codes were added as new themes and subthemes emerged. The key findings regarding community perspectives on skin infections; healthcare practitioner perspectives on the clinical management and specific treatment options for skin infections; and practices, considerations and preferences are presented.

Ethics approval

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants with the exception of one participant, who provided oral assent to participate. Confidentiality and anonymity of all participants was assured and no personal details were recorded. Ethics approval was obtained from the Western Australian Aboriginal Health Ethics Committee (HREC 510) and the University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Office (RA/4/1/6563).

Results

Perceived child health issues in the communities

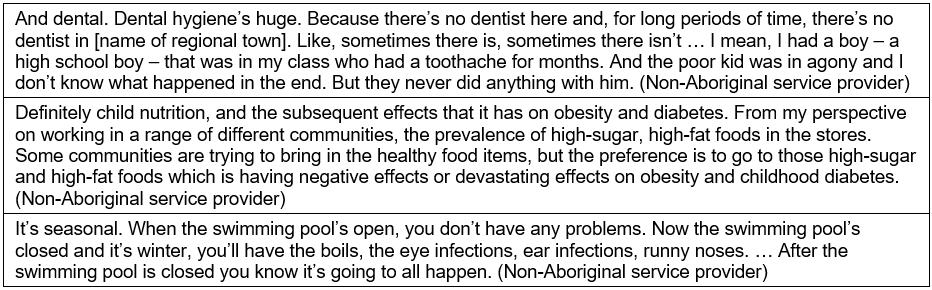

All participant groups raised the issue of skin infections, particularly the burden on children. Poor nutrition due to a lack of access to affordable, healthy food options in local community stores was raised as contributing to skin infections, poor dentition and early onset diabetes. Some parents and service providers believed skin infections had decreased since improvements to the community’s water supply and establishment of a swimming pool (Box 1).

Healthcare practitioners reported skin infections as a dominant health issue among children presenting to the clinic. Most differentiated scabies, fungal infections, ring worm, boils, sores, impetigo and dermatitis, whereas parents/carers referred to ‘sores’ for all skin infections.

Box 1: Quotes illustrating broad health issues within the communities.

Box 1: Quotes illustrating broad health issues within the communities.

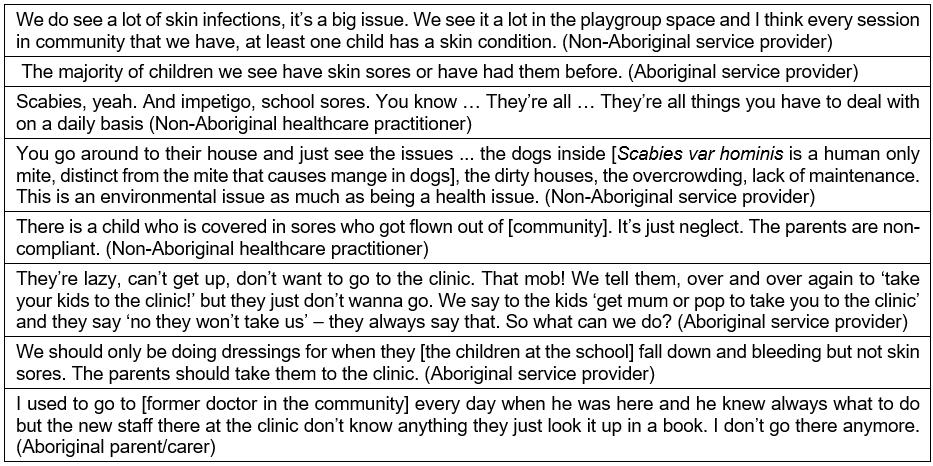

Community service provider/healthcare practitioner perspectives on skin infections

Community service providers reported that the pain and discomfort associated with skin infections affected children’s health, general wellbeing and ability to concentrate and participate at school. While most acknowledged the importance of treating skin infections, they were also unaware of the serious health consequences associated with bacterial skin infections (eg acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis and acute rheumatic fever).

Healthcare practitioners described the sequelae, if not the mechanism, leading to such complications, although most were unfamiliar with crusted scabies and its clinical presentation as a mite hyper-infestation. Most parents/carers and service providers lacked confidence in healthcare practitioner knowledge and ability to adequately manage skin infections.

Both of these groups considered housing and living conditions (including overcrowding, inadequate housing and cleanliness), environmental factors, hygiene practices and malnutrition as reasons for widespread skin infections within these communities (Box 2).

Box 2: Quotes illustrating community stakeholder perspectives on skin infections.

Box 2: Quotes illustrating community stakeholder perspectives on skin infections.

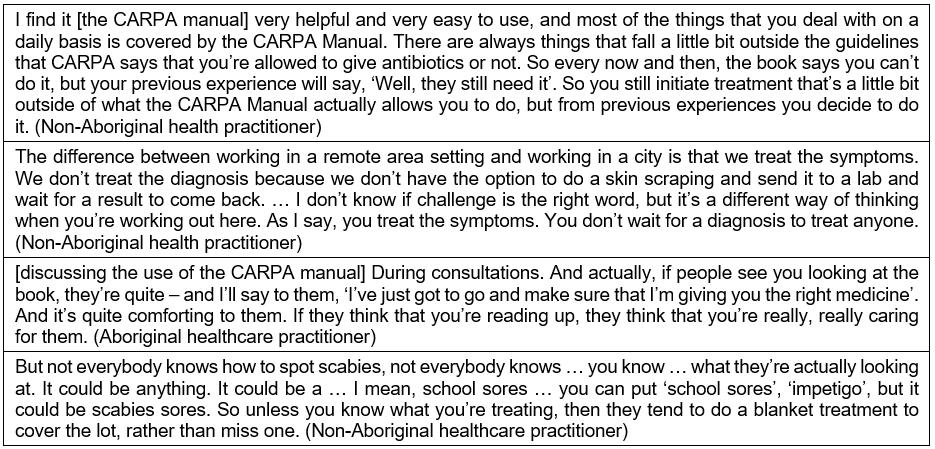

Healthcare practitioner perspectives on clinical management of skin infections

All healthcare practitioners referred to the Central Australian Rural Practitioners Association (CARPA) manual11 as an essential guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of skin infections. However, some used treatment outside the CARPA recommendations such as Bactroban (mupirocin), a topical antibiotic that is contraindicated in the CARPA manual, due to the risk of antimicrobial resistance22.

Most healthcare practitioners found skin infections challenging to diagnose as presentations often look similar or present atypically and there was lack of clinical guidelines and resources to assist in the diagnosis. When presented with photographs of scabies and skin sores (Fig1), few healthcare practitioners could accurately diagnose or gauge the severities of sores.

While the presence and severity of fever and pain generally determined the choice of treatment, some healthcare practitioners were reluctant to prescribe antibiotics for fear of increasing resistance. This was confirmed by evidence that contrary to guidelines 28% of children with standard skin sore presentations were not prescribed antibiotics23. Generally, less severe sores were cleaned and antiseptically dressed (eg with Dettol (Reckitt Benckiser, UK; active ingredient chloroxylenol, an antiseptic), ‘medicated soap’ and ‘medicated bubble bath’); more severe and widespread infections required antibiotics (Box 3).

Box 3: Quotes illustrating general healthcare practitioner perspectives on the clinical management of skin infections.

Box 3: Quotes illustrating general healthcare practitioner perspectives on the clinical management of skin infections.

Specific treatment for skin infections: practices, considerations and preferences

Benzathine penicillin G injection and oral antibiotics for skin sores: Most healthcare practitioners used BPG injection for skin sores (consistent with the CARPA manual)11 given its single dose administration and long half-life. This preference was informed by their concern regarding parent/carer lack of adherence to using oral antibiotics and household refrigeration for storing them.

Notwithstanding the practical advantages of BPG, all participant groups regarded the painful injection as a barrier, instilling fear of the clinic in young children, and adversely affecting future healthcare seeking behaviour. For this reason, some healthcare practitioners considered oral antibiotics as a positive alternative.

Many parents/carers spoke about the ‘pain’ and ‘fear’ associated with the needle and its traumatising effect on their children. One parent, however, reported that their child had requested the needle, based on previous experience of being hospitalised due to the skin infection (Box 4).

Box 4: Quotes illustrating practices, considerations and preferences regarding benzathine penicillin injection and oral antibiotics for scabies.

Box 4: Quotes illustrating practices, considerations and preferences regarding benzathine penicillin injection and oral antibiotics for scabies.

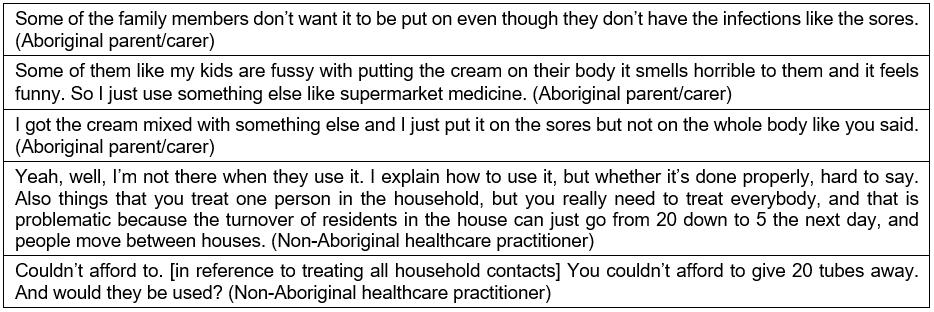

Permethrin cream (Lyclear) for scabies: All healthcare practitioners were familiar with permethrin cream as the treatment for scabies and had provided it to parents to apply to their children at home. Some, however, were unaware of the CARPA guidelines and the need to apply the cream to the entire body, including the head and face, instead instructing parents/carers to apply the cream from the neck down or spot-treat scabies infected areas of the body. Additionally, few healthcare practitioners adhered to CARPA guidelines to treat all household members to avoid re-infestation, citing large turnover of household members and the high cost to the clinic of treating a number of people.

Not surprisingly, parents/carers also expressed confusion regarding the application process for using the scabies cream. Many were not aware of the need to apply the cream to the entire body. Some carers spoke of the smell, the ‘funny’ texture, and the time it took for the skin infections to heal when using the cream as potential barriers to treatment uptake (Box 5).

Box 5: Quotes illustrating practices, considerations and preferences regarding permethrin cream.

Box 5: Quotes illustrating practices, considerations and preferences regarding permethrin cream.

Parent/carers perspectives regarding treatment and care

Parents/carers using permethrin cream as the treatment for scabies identified the need for more holistic and culturally appropriate care and an active follow-up and recall system to promote adherence to oral antibiotics. They suggested healthcare providers need to provide more information on the critical importance of skin health and treating skin infections properly. Parents/carers reported that healthcare providers seldom involve them in decision-making regarding the use of BPG injection or oral antibiotics for skin sores

Parents/carers (many speaking English as a third or fourth language) reported several challenges in adhering to oral antibiotics. They found healthcare practitioner language regarding how and when to use antibiotics too complex, making it difficult to follow directions or understand the need to complete the course of antibiotics. Some also found the taste of the syrup and the size of the tablets undesirable. They suggested storing oral antibiotics at school to be administered by teachers, and having nurses or Aboriginal health workers visit the playgroups or their homes for this purpose.

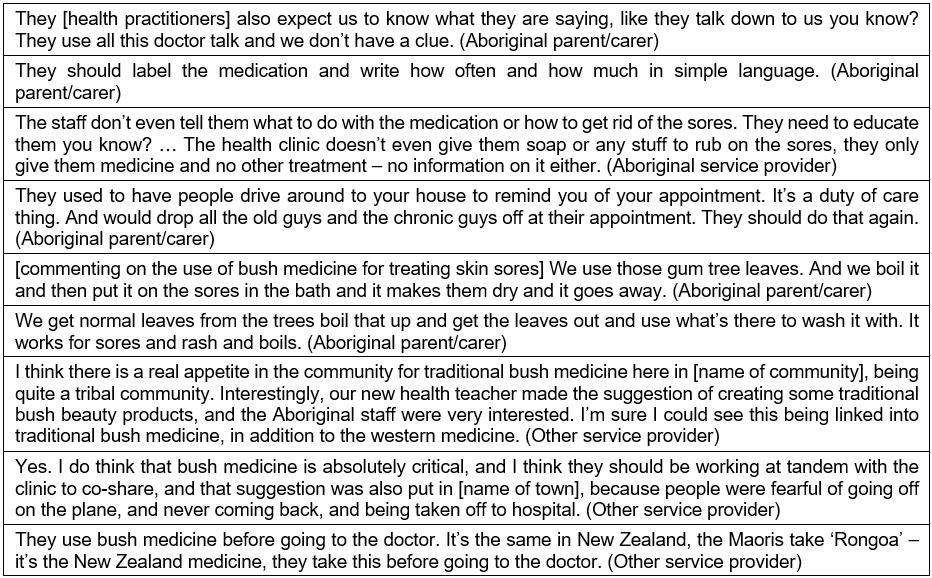

Use of ‘bush medicine’

Most parents/carers discussed the effectiveness of ‘bush medicine’ for themselves, their children and families in treating scabies and skin sores. All participants acknowledged the use and benefits of traditional ‘bush medicine’ for treating skin infections, an idea supported by some healthcare professionals who agreed it could be beneficial to explore the use of bush medicines in conjunction with western medicine.

Box 6: Quotes illustrating parent/carers and service provider perspectives regarding skin treatment and care

Box 6: Quotes illustrating parent/carers and service provider perspectives regarding skin treatment and care

Discussion

This is the first qualitative study in a remote Aboriginal community setting to document parent/carer, healthcare practitioner and service provider attitudes and practices regarding skin infections, and their perceived impact on child health and wellbeing. This study reveals that skin infections are a normalised yet pervasive child health and development issue, which adversely impacts on children’s wellbeing and school participation. The findings are consistent with previous studies in remote communities showing high rates of clinic presentations for skin infections24, with a recent community clinic audit in the same communities showing 16% of childhood presentations for skin infections23.

Healthcare practitioners were typically aware of the high prevalence, types of skin infections, the potential long-term impacts and the need for effective diagnosis and treatment regimens, although treatment guidelines were not always followed. Moreover, there is a sense of normalisation where the high rate of skin infections among children in the community is widely acknowledged, but not considered a priority. A similar study in remote Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory in Australia shows that the high prevalence of skin sores creates a tendency for multiple skin sores to be ‘normalised’25. A recent review of hospital presentations in the Pilbara found that normalisation also affects healthcare practitioners, resulting in the systematic under-diagnosis of up to 60% of skin infections amongst Aboriginal children26. The findings highlight the critical need for education for healthcare practitioners to create greater awareness of the importance of skin infection diagnosis, treatment and adherence to CARPA guidelines.

Parents/carers reported a range of challenges that affect their adherence to skin treatments including practical limitations with adherence to oral antibiotics and topical scabies treatment, and fear of painful BPG injection. Several parents/carers emphasised the need for healthcare practitioners (and service providers) to communicate more clearly and to more effectively engage with and strengthen the capacity of communities to support the healthcare needs of their children. The importance of cultural sensitivity and acknowledgement of differing conceptions of health was most evident when bush medicines were discussed. These findings highlight the need to involve communities in developing local, regional and national strategies for improving the prevention and control of skin infections to address their specific concerns.

Despite the burden of disease, clinical recognition and diagnosis remains the main method for treating scabies in remote communities27. The under-recognition and under-diagnosis of skin infections requires diagnostic tools to meet the specific needs and challenges of health care in low-resource settings28. Most healthcare practitioners described the precise diagnosis of skin infections as challenging and dependent on their experience and ability to interpret clinical signs and symptoms, in the absence of rapid diagnostic tests, leading to a process of trial and error. Many highlighted the need for resources to assist the clinical diagnosis of skin infections and support community education. Such a resource has recently been launched as part of the National Healthy Skin Guidelines for Indigenous Communities in Australia29.

The CARPA manual in use at the time preferenced BPG injection for skin sores as the first-line treatment option11. However, this is the first study where the pain and discomfort from an injection of BPG was described by all study participants as a major barrier to healthcare seeking behaviour. This affirms a previous study where the pain of BPG injections was hypothesised as a likely reason for poor treatment uptake in skin control programs25 and formed the basis of the Skin Sore Trial, during which a short course of oral antibiotics was trialled to improve treatment uptake for skin sores15.

Children can experience higher anxiety and subjective pain compared to adolescents and adults30. Parents/carers and service providers spoke of children ‘walking funny’ and being in pain for several days after the injection, consistent with an earlier study showing that one third of children experience ongoing pain 2 days after the injection, and several children declined participation in a trial when randomised to BPG15. Parents/carers also found the procedure distressing, similar to parent reports in other remote settings in Australia, where BPG is administered for secondary prophylaxis of rheumatic heart disease31. Strategies such as warming the needle, mixing lignocaine with the BPG, applying a cold pack prior to injection and other pain minimisation tools are currently not included in the CARPA manual30-32 and their implementation depends on the healthcare practitioner’s training and experience.

Oral antibiotics for the treatment of skin sores were recommended by the 2014 CARPA manual at the time of this study only when the BPG injection is deemed ‘not possible’11. While parents/carers generally preferred oral antibiotics to avoid the pain associated with the injection, they identified several barriers including palatability, lack of refrigerators for storage, ceasing medications early due to a lack of understanding of the need to complete the course of medication, or simply forgetting amid competing family demands.

Antibiotic adherence to long-term medication for chronic diseases is poor throughout the world, with approximately 50% adherence in developed countries, and less in resource-limited settings33. Although there is limited literature for skin infections, compliance with oral iron tablets is poor in remote Aboriginal communities34. In addition, poor adherence in remote Aboriginal communities is attributed to lacking a home refrigerator for storing antibiotics35 social, economic, health system factors, characteristics of the disease and patient-related factors36. Healthcare providers need to be aware of these factors to support parents and carers to overcome poor adherence to treatment regimens36. This study adds greater clarity to the importance of reform in this area through the voices of parents/carers and community service providers.

For the treatment of scabies, the CARPA manual recommends two full-body applications of permethrin cream, 1 week apart11. The study findings suggest that the successful completion of the treatment regimen is undermined because of inappropriate application of the cream (not covering the entire body), the time it takes for the scabies infestation to clear or the itching symptoms to subside, and the unpleasant smell and texture of the cream. Similar barriers have been documented elsewhere, as well as a lack of privacy in overcrowded homes to apply the cream and poorly functioning bathrooms for washing the cream off13,25.

Use of traditional ‘bush medicines’

A previous study reinforces the potential benefits of traditional treatments and found Aboriginal people generally seek traditional treatment remedies prior to western practices37. Acknowledging Aboriginal traditional cultural identity and local knowledge, particularly bush medicine management, is crucial for prevention of chronic diseases among Australian Aboriginal people38. Using traditional bush medicine is a priority for Aboriginal people to restore and protect their culture and gain a sense of control and ownership over their health and wellbeing38. A New Zealand study also found that acknowledging existing knowledge and cultural beliefs is effective in educating parents and improving health outcomes for children39. The potential use of bush medicine for the treatment of skin infections and its integration in remote Aboriginal community clinical practice is being further explored with the study communities.

Further, parent/carers requested clear, illustrated, plain (and Martu) language, instructions around treatment options: what the medication is for, how to apply or take it and why it is important. These findings also confirm the need for education of healthcare practitioners, health services and parents/carers to improve their knowledge and understanding of health protocols, similar to other research findings40. However, despite that the majority of Martu parents and carers do not speak English as their first language, clear treatment instructions and the use of interpreters are lacking. The failure to use interpreters and to translate health information contributes to the continued health inequities and is a form of institutionalised racism41. To address these identified shortfalls a resource is being developed to promote empowerment, avoid misunderstandings around treatment uptake and medication completion.

Limitations

There are several limitations in interpreting the findings and translating them in a broader context. First, researchers were non-Aboriginal and performed data analysis and interpretation from their perspective. However, member checks with Martu, other participant groups and senior Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal researchers ensured the reliability of the information42. Second, the high turnover of healthcare practitioners and service providers, and mobility among Martu families moving between the four communities and the town, mean that the findings are reflective of participants present at the time of the study. Although parents/carers were only interviewed in one community and the regional town, their mobility across the communities enhances their likely representation. Feedback has since been checked with Martu leaders representing all communities, who have confirmed the findings. Third, in discussing different treatment regimens it was often difficult to ascertain whether parents/carers and service providers were referring to scabies or skin sores (impetigo), as both groups generally referred to ‘sores’.

Conclusions

The study findings provide important and unique insights into the current knowledge gaps and education needs in regards to skin infections and their treatment among Aboriginal children living in remote communities. Using these findings to inform health policy and practice guidelines and develop partnership opportunities could help reduce the burden of skin infections in these communities, and improve the health, wellbeing and early development outcomes of Aboriginal children living there. More effective prevention and control of skin infections in remote Aboriginal communities requires community education on the importance of skin health; improving antibiotic adherence; implementing recall systems; providing home visits; engaging with schools; improving healthcare practitioner cultural competence and familiarity with, and adherence to, skin infection treatment guidelines; and ensuring clear and appropriate communication to parents/carers on treatment procedures. This study also identified the need for a collaborative and empowering approach that engages parent/carers in decision-making regarding treatment options for scabies and skin sores, including the potential value of bush medicines.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Puntukurnu Aboriginal Medical Service. We thank the Martu families, healthcare practitioners, community workers and agency stakeholders including World Vision Australia and YMCA who participated in the study. It was conducted with support and guidance of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal chief investigators from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Centre for Research Excellence in Aboriginal Health and Wellbeing (CREAHW) (APP1000886). DH was funded through a University of Western Australia International Scholarship and the Stan Perron Charitable Trust. DH and RW were supported with funding through the NHMRC CREAHW (APP1000886). IAD was awarded the Anne and Peter Hector Scholarship through the Telethon Kids Institute to support this study. AB receives an early career fellowship from the NHMRC (1088735).

References

You might also be interested in:

2015 - Analysis of barriers to adoption of buprenorphine maintenance therapy by family physicians