Introduction

Rural and remote mental health is a longstanding concern in Australia and across the world1. Similar to global findings, the Australian Rural Mental Health Study found little difference in prevalence of mental health disorders between rural and urban residents2. However, suicide rates in rural areas are significantly higher. In 2012-2016, men who lived in very remote areas were two times more likely to die by suicide than men in major cities, whilst men who lived in outer regional areas were 1.5 times more likely to take their own life compared to men who lived in major cities3. Females across location followed a similar, albeit weaker, pattern3.

The rural Australian stereotype comprises several common themes from previous studies including geographical and social isolation, reluctance to discuss problems, conservative attitudes and values, lack of viable healthcare options and specialists, and reliance upon external factors such as the weather4-6. Those rural features have been associated with higher rates of suicide in rural and remote Australia. In addition, occupations rooted in agriculture, forestry or fishery, which are naturally more prevalent in rural locations, may contribute to the elevated risk of suicide5-8, considering their increased access to lethal means9, long working hours10, social isolation11 and dependency on natural events12,13. The gun culture produced by regular hunting, a general acceptance of the value of guns14 and a functional approach to death (eg animal euthanasia)15 by many rural Australians may act as another risk factor.

Considering lower levels of help-seeking in rural residents16, there is significant research into the barriers preventing help-seeking. Limited access to mental health professionals such as psychologists is a longstanding issue for rural communities. Access to qualified staff is usually limited as there is a lack of specialists in rural areas17. Furthermore, rural residents have been found less likely to engage with psychiatrists and psychologists for a psychological problem than their metropolitan counterparts, after controlling for limited access18.

The rural lifestyle has long been considered a domain where the people are ‘tough’. Rural people, particularly males, are traditionally considered physically and emotionally strong, and able to solve their own problems19,20. The concept of ‘Aussie battlers’ is constantly portrayed in the media, where any form of reduced masculinity is perceived as weakness21,22. The rural ideology generally suggests residents are self-reliant and prefer to suffer in silence23. Fuller et al24 determined that the self-reliant attitudes encompassed by many rural Australian residents made it difficult for people to even acknowledge they were having difficulties and experiencing distress. Difficulty acknowledging distress is also likely to influence help-seeking behaviours because, in order to seek help, a person must recognise that they require it25. A factor that may exacerbate a male’s ability to detect mental health difficulties is that they are more likely to encompass many physical symptoms of depression such as sleeplessness, feeling ill or lack of motivation11,26. Extending on this, males appear to exhibit externalising behaviours such as aggressiveness or substance abuse when depressed or suicidal, rather than internalised symptoms such as low mood20. Such physical and externalising symptoms, if unaccompanied by obvious low mood usually typical of depression, may prevent men from recognising their own mental health difficulties.

One trait exemplified within rural Australia is stoicism. Stoicism is defined as the endurance of pain or hardship, without the display of feelings and without complaint. Wagstaff and Rowledge27 suggest denial, suppression and emotion control are the key components of stoicism. The values embraced by many rural people and promoted as those of the ‘Aussie battler’ encourage ‘getting on with it’ as an effective and admirable coping strategy. Therefore, it is unsurprising that evidence suggests higher levels of stoicism are prevalent within rural contexts23,28. Being stoic is related to the tendency to actively avoid situations where there will be encouragement to discuss thoughts, emotions and problems25. Based on these findings, it is expected that stoicism has been linked to lower help-seeking intentions for psychological issues29.

To the authors’ knowledge, previous studies have not investigated the impact of rurality on help-seeking intentions or predictors of help-seeking such as stoicism and attitudes. Therefore, the current study aimed to further investigate whether rurality, stoicism and attitudes predict help-seeking intentions and whether predictors of help-seeking intentions differ by rurality (urban v rural).

Methods

Procedure

The online questionnaire was set up in Qualtrics software (Qualtrics; http://www.qualtrics.com). Participants were members of the community who accessed the study through word of mouth and its promotion on personal social media channels such as Facebook. The study was also promoted through the Australian Institute of Suicide Research and Prevention social media channels. An article about mental health in rural communities and promoting the survey was published in The Land newspaper. The purpose was to increase the number of rural participants. Participants were recruited over a period of 6 months between February and July 2018. Participation was voluntary and anonymous and took approximately 20 minutes. At the end of the questionnaire, the software directed participants to a debrief sheet. Participants were then given the option to provide their email address (in a separate database to ensure anonymity) to go into the draw to win one of three $50 retail vouchers for their participation.

Measures

Rurality: Participants were asked to provide their postcode, which was converted into Accessibility and Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA) classification for rurality where 1=major cities, 2=inner regional, 3=outer regional, 4=remote and 5=very remote4.

Demographics: Participants were asked their age, gender, Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander status, marital status and employment status/occupation.

The General Help-Seeking Questionnaire30: This is a 10-item scale designed to measure an individual’s intention to seek help from a range of sources (including intimate partner, family member, doctor, mental health professional) for a personal or emotional problem. Responses are scored on a seven-point Likert scale from 1=extremely unlikely to 7=extremely likely, where higher scores indicate a higher likelihood of seeking help from that source. The final item, ‘I would not seek help from anyone’, is the reverse, where higher scores indicate less motivation to seek help from any source. This item was reverse scored and items were added to form a general likelihood of help-seeking. Participants can score between an arbitrary range of 7 and 70. The internal reliability was adequate for this questionnaire (α=0.74).

The Liverpool Stoicism Scale27: This is a 20-item scale designed to assess an individual’s level of stoic beliefs and behaviours. The questionnaire encompasses three key domains of stoicism: lack of emotional involvement, a dislike of free emotional expression and an ability to endure emotion. Responses are recorded on a five-point Likert scale of 1=strongly disagree through to 5=strongly agree. Eleven items were reverse scored so that the higher the total score, the higher the level of stoicism. Participants can score between an arbitrary range of 20–100. The internal reliability was adequate for this scale (α=0.85).

Attitudes toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale31: This 29-item scale is designed to measure general attitudes about seeking help for psychological problems. The questionnaire consists of four subscales including recognition of need for psychological help, stigma tolerance, interpersonal closeness and confidence in mental health professionals. Items are measured on a four-point Likert scale from 1=strongly disagree to 4=strongly agree. Eleven items were positively framed (eg ‘If I thought I needed psychological help I would get it no matter who knew about it). Remaining items were reverse scored so that the higher the total score, the more favourable one’s attitudes toward seeking help from mental health professionals. Three items were removed because very similar items appeared in the Liverpool Stoicism Scale. Participants can score between an arbitrary range of 29–116. Nevertheless, the internal reliability was high for this scale (α=0.90).

Statistical analysis

Little’s Missing Value Analysis indicated that there was no systematic variation between missing data points and data was Missing Completely At Random (Little’s MCAR test) and missing values were substituted using multiple imputations. The χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test (less than five per group) was used to compare different groups. Multiple linear regression was used to predict the score of help-seeking intentions. All scales had normal distribution (the range for skewness or kurtosis below +1.5 and above −1.5) and all variables include were centred. In addition, the Process model for bootstrapping mediation was used to determine if attitudes mediated the relationship between stoicism and help-seeking intentions separately in urban and rural areas. Bootstrapping was the statistical model chosen because it estimates both the direct and indirect effects and has more power to find an indirect effect compared to the causal steps approach32. An arbitrary threshold of significance was used where p-values were less than 0.05.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committee (GU Ref No: 2017/910).

Results

In total, 698 participants started the survey. However, 207 participants (29.7%) failed to complete the survey, 7 participants (1.0%) provided invalid postcodes and 13 participants (1.8%) did not indicate their age or were younger than 18 years and were removed from the database. This resulted in 471 participants (67.5%) having completed the study (36.3% male; 63.5% female; 0.2% preferring not to answer). Age range was 18–85 years (mean=41.10, standard deviation=15.19), including 11 participants identifying as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander (2.3%). Majority of participants were in a de facto relationship or married (55.4%). The most commonly reported occupation was agriculture, forestry or fishing (42.0%). Other reported occupations included health (11.3%) and education and training (13.2%). Approximately half of the participants had engaged in psychotherapy with a mental health professional (51.8%). More than one-third had been diagnosed with a mental illness (41.4%), while more than half of the participants had contemplated suicide (58.4%). Little’s MCAR test found the data were randomly missing across the entire data set (χ214011=14261.27, p=0.068; N=471).

Rurality

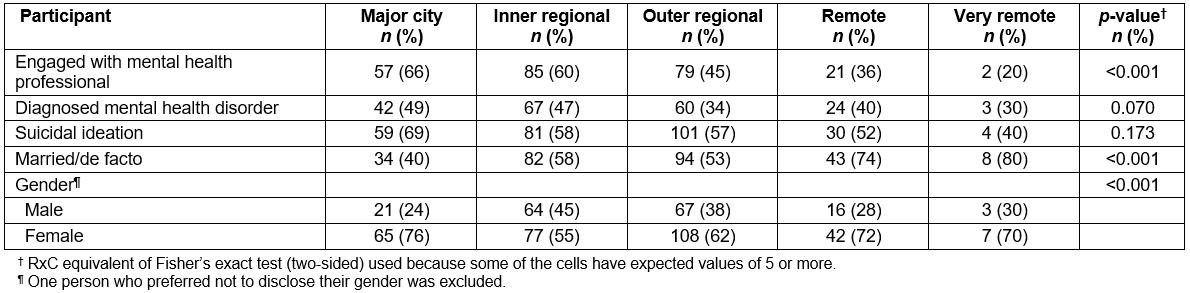

Participants were relatively well spread by rurality (ARIA classification category). Most participants resided in outer regional areas (37.4%), followed by inner regional (29.9%), major city (18.3%), remote (12.3%) and very remote (2.1%) areas. A series of χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests showed that participants in different rurality categories differed significantly by sex, marital status and having a diagnosed mental illness (Table 1).

Table 1: Study participants by rurality

Regression analyses

Prior to conducting the hierarchical multiple regression, the relevant assumptions of this statistical analysis were tested. Adequate sample size, assumption of singularity, assumption of multicollinearity and assumptions of normality, linearity and homoscedasticity were all satisfied and all variables were centred.

A two-stage hierarchical multiple regression was conducted with help-seeking intentions as the dependent variable. Sex, age, diagnosed mental illness, suicidality, marriage status, previous engagement with a mental health professional, stoicism and attitudes were added to the model at stage 1 to control for well-known predictors of help-seeking intentions. ARIA code was entered at stage 2 of the model. The hierarchal multiple regression revealed that, at stage 1, the predictors explained 32.3% of the variance (R2=0.323, F(8,461)=28.95, p<0.001) in help-seeking intentions. Adding ARIA code to the model at stage 2 explained an additional 1.2% (R2=0.012, F(1,460)=8.66, p=0.003).

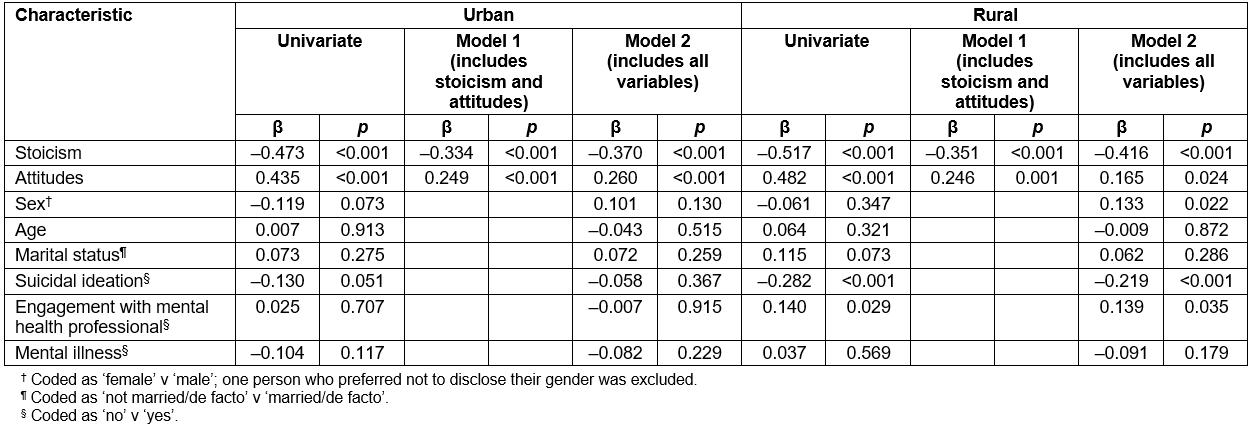

In addition, univariate and multiple regression analyses were conducted to test whether predictors of help-seeking intentions differed in urban and rural locations (Table 2). The first multiple regression tested rural participants (ARIA codes 3, 4 and 5). The regression included sex, age, marital status (married/de facto v not), diagnosed mental illness, suicidal ideation, previous engagement with a mental health professional, stoicism and attitudes as predictors, and help-seeking intentions as the dependent variable. The predictors explained 36.7% of the variance (R2=0.367, F(8,234)=16.96, p<0.001) in help-seeking intentions in rural location. Significant predictors included sex (β=0.13, p=0.022), suicidality (β=–0.22, p=0.001), stoicism (β=–0.42, p<0.001), attitudes (β=0.17, p=0.024) and engagement with a mental health professional (β=0.14, p=0.035). A regression model with the same variables was tested predictors for urban participants (ARIA codes 1 and 2). The predictors explained 27.1% of the variance (R2=0.271, F(8,218)=11.50, p<0.001) in help-seeking intentions. Significant predictors included only stoicism (β=–0.37, p<0.001) and attitudes (β=0.26, p<0.001).

Table 2: Univariate and multiple standardised regression coefficients predicting help-seeking intentions in urban and rural areas

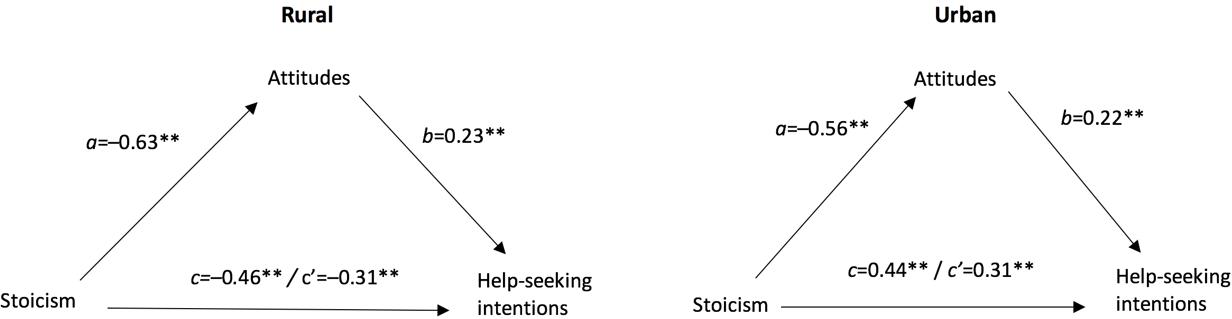

Mediation analyses

Considering the results showed potential mediation effect of attitudes between stoicism and help-seeking intentions (Table 2), the authors conducted further mediation analyses. Mediation models were also tested separately for rural and urban participants (Fig1). For rural participants, the 95% bias corrected confidence interval was between –0.227 and –0.063, indicating a significant indirect effect. The total (path c) and direct effects (path c') of stoicism on intentions to seek help were b=–0.46, p<0.001 and b=–0.31, p<0.001, respectively. Attitudes partially mediated the relationship between stoicism and help-seeking, with the model accounting for 26% of the variance in help-seeking (adjusted R2=0.26, F(1,242)=88.16, p<0.001). Participants reporting high levels of stoicism were more likely to have negative attitudes toward help-seeking, and they also reported lower intentions to seek help.

For urban participants, the 95% bias corrected confidence interval was between –0.205 and–0.090, indicating significant indirect effect. The total (path c) and direct effects (path c') of stoicism on intentions to seek help were b=–0.44, p<0.001 and b=–0.31, p<0.001, respectively (Fig1). Attitudes partially mediated the relationship between stoicism and help-seeking, with the model accounting for 22% of the variance in help-seeking (adjusted R2=0.22, F(1,225)=64.75, p<0.001). Participants reporting high levels of stoicism were more likely to have negative attitudes toward seeking help, and they also reported lower intentions to seek help.

Figure 1: Mediation analysis between stoicism and help-seeking intentions through attitudes for rural and urban participants.

Figure 1: Mediation analysis between stoicism and help-seeking intentions through attitudes for rural and urban participants.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate using an online survey how rurality in addition to other factors impacts on help-seeking intentions using multivariate analysis and whether factors predictive of help-seeking intentions differ in urban and rural settings. In addition, the study used a mediation analysis to explore the role of attitudes toward mental health professionals and stoicism on help-seeking intentions for mental health concerns. Key findings showed that rurality (as separated by ARIA code) did predict help-seeking intentions in the final model. In line with previous recommendations by Caldwell et al18, the present study also highlighted the need to recall differences between all regions rather than using dichotomous groupings for rurality. Avoiding dichotomous groupings was not possible for all analyses; nevertheless, stoicism and attitudes did predict significantly the help-seeking in both urban and rural areas. Furthermore, attitudes toward seeking professional help would partially mediate the relationship between stoicism and intentions to seek help.

The present study determined that rurality predicts help-seeking intentions: intentions to seek professional help for a mental or emotional problem decrease with the higher degree of rurality using ARIA classification. This is not surprising considering previous research has shown several barriers to seeking help in rural and remote areas, including stoic ideals23, isolation2, stigma33 and negative attitude toward mental health professionals15. Concerns regarding anonymity and privacy in rural towns also influence help-seeking34. Due to the limited access faced by remote participants, mental health professionals are exploring the validity and feasibility of online help-seeking resources for rural and remote people35. Although the current study did not explore online help-seeking, it may be a source of help for people living in outer regional and remote areas.

People who have experienced suicidal ideation had lower help-seeking intentions than those who had not. Stigma associated with suicide in communities, is likely to deter individuals who may be experiencing suicidal ideation from seeking help. The ‘help negation’ effect explains that the more suicidal thoughts a person has, the less intention they have to seek help36. The help negation effect is maintained regardless of prior help-seeking experiences and helplessness37. Rural communities in the Netherlands with a higher suicide rate had lower intentions to seek help for mental distress compared to similar communities in Belgium with lower suicide rates38. However, previous exposure to mental health professionals was also found to predict higher help-seeking intentions for rural participants. In line with current results, Vogel et al39 found having prior experience with mental health professionals was a positive indicator of future help-seeking.

Males also reported lower help-seeking intentions than females in rural areas, but not in urban areas. This is congruent with previous research suggesting rural men typically endorse more stoic views and a desire to solve their own problems29. Higher levels of stoicism combined with poorer attitudes toward mental health professionals may exacerbate men’s tendency to have lower help-seeking intentions as well. This idea is in line with Judd and colleague’s research23 who found gender was no longer a significant predictor of help-seeking intentions when attitudes were controlled for.

Attitudes are a well-known barrier to seeking help for mental health issues40, so it was not surprising that attitudes were also a significant predictor for help-seeking intentions for both rural and urban participants. Similarly, stoicism was also found to be a significant predictor for help-seeking intentions for both rural and urban participants. Being stoic is related to the tendency to actively avoid situations where there will be encouragement to discuss thoughts, emotions and problems, so it is unsurprising it is likely to influence help-seeking. Previous findings have also determined that a high level of stoicism is related to lower help-seeking intentions for psychological issues29.

A mediation model showed that attitudes partially mediated the relationship between stoicism and help-seeking intentions for both rural and urban participants. Much of the current research suggests the rural lifestyle as a barrier to help-seeking16,17,20. However, the present study suggests that negative attitudes, an entirely malleable factor, partially explain the relationship between stoic ideals and help-seeking intentions, regardless of location. The need to be stoic endorsed by Australian society may not be as pliable as attitudes, and therefore targeting attitudes during preventative interventions may be more plausible. Emerging evidence suggests stigma and attitudes toward help-seeking and mental health disorders can be improved with education-oriented programs, usually in secondary school or university settings41.

A number of limitations should be noted. First, participants were recruited from several sources, including social media channels, Australian Institute of Suicide Research and Prevention contacts and The Land newspaper, with the goal of reaching as many participants as possible, particularly from rural communities where recruitment is notoriously difficult. The Land newspaper is primarily based in New South Wales, limiting recruitment initiatives in other states and territories throughout Australia. Therefore, the results in this study may not generalise to all communities throughout Australia but rather depict a general pattern.

Second, the study utilises a help-seeking intentions measure, rather than tracking participants’ actual help-seeking. Removal of three items from the attitudes scale and use of rurality as dichotomous (rural v rural) for some analyses should be also considered as limitations. In addition, emerging research suggests help-seeking intentions may not accurately predict help-seeking in reality42. Finally, the cross-sectional study design does not allow the determination of causality.

Conclusion

This study has a few implications for clinical intervention and community prevention. Understanding how geographical locations differ on well-known predictors of help-seeking can help develop specific initiatives designed to assist an area based on its explicit needs. Currently, the majority of initiatives aimed at closing the gap between rural and metropolitan mental health and suicide rates is to focus on increased access to mental health specialists such as psychologists and psychiatrists. This research suggests other factors such as stoicism and attitudes need to be addressed in order to encourage help-seeking and understand suicidal behaviours. As attitudes to seeking professional help partially mediated the impact of stoicism on help-seeking intentions, strategically influencing negative attitudes may improve help-seeking intentions for rural participants. This is particularly important because attitudes are likely to be more pliable than robust personality factors such as stoicism. Future research should be rooted in continuing to understand the malleable factors influencing help-seeking such as attitudes and developing programs to strategically target them at the community level. Employing e-mental health strategies in conjunction with malleable factors may also be an avenue for future research to address the limited help-seeking in rural areas not explored in this study. To address the present study’s limitations, utilising a longitudinal design may assist in understanding how factors such as attitudes and stoicism may change over time and by location regarding active help-seeking rather than relying purely on help-seeking intentions.