Introduction

The increase in life expectancy of populations is making new demands on health systems, including the challenge of maintaining functional status and quality of life.

Physical decline during aging may lead to functional dependence, which is the need for assistance to perform activities of daily living. Functional dependence relates to activities such as use of the toilet, feeding, transferring, dressing, walking upstairs and bathing, as well as urinary and fecal continence1.

In developing countries such as Brazil, the evidence that older people today are in better health than their parents is unclear. According to a systematic review, functional dependence among urban Brazilian older adults ranges from 13.2% to 85.0%2. It highlights that most of the studies are from south and south-eastern regions and include different populations and sampling processes. Factors such as cognitive deficit, depression, chronic conditions, multiple illnesses, malnutrition, overweight, functional limitation in the legs, sedentary lifestyle and visual impairment are risk factors for functional dependence3. Female sex, older age and lower level of education have also been found to be consistently associated with functional dependence2-4.

Although elderly people from isolated communities usually have poorer health than urban counterparts5, the prevalence of and factors associated with functional dependence among rural elderly are poorly understood in Brazil. Rural specificities such as long distances, mobility restrictions, poor access to health services as well as architectural barriers may worsen the living conditions of elderly people with functional dependence.

The objective of this study was to estimate functional dependence prevalence and its associated factors among community-dwelling older adults in the rural area of the municipality of Rio Grande, Rio Grande do Sul state, Brazil.

Methods

This cross-sectional, population-based study was conducted in the rural area of the municipality of Rio Grande, Rio Grande do Sul state, Brazil. Rio Grande is a municipality in the southern of Rio Grande do Sul state, located between Lagoa dos Patos and the Atlantic Ocean, with an area of 2708.4 km2. This port city is an export corridor for commodities such as soybean and rice. Its rural population is dispersed over a vast territory and includes traditional communities formed mainly by Azorean migrants, such as those on the islands Ilha dos Marinheiros and Ilha da Torotama, who live mainly from fishing and traditional agriculture6.

In the year of data collection, the population of Rio Grande was approximately 209 000 inhabitants. Of this total, approximately 8500 inhabitants lived in rural areas, of whom 13% were older adults7. Regarding health services, the Family Health Strategy has 100% coverage in rural areas of Rio Grande. The strategy was initially developed in Brazil to provide primary healthcare access in remote and low-income communities. Family Health teams are responsible for the health of residents of a defined territory and seek to promote the quality of life of the population, prenatal care, maternal and child health and control of chronic, non-communicable diseases8.

The data presented here are part of the study entitled ‘Health of the rural population of Rio Grande’, whose objective was to obtain information about health conditions of children aged less than 5 years, women of childbearing age (15–49 years) and older adults (aged 60 years or more). This third group was the target population of the present study. All older adults living in the rural area of the municipality were eligible for the study.

A systematic random sampling process was used in order to select 80% of the permanently inhabited households in the municipality’s rural area. Researchers drew a number between 1 and 5. The drawn number corresponded to the household to be skipped – for example, if number 3 were drawn, every third household in a sequence of five would be skipped and left out of the sample. This procedure guaranteed that four in every five (80%) of households were included in the sample9. Data collection took place between April and October of 2017 and was done by interviewers who had been trained in administering the questionnaires. All the information was obtained using two standardized questionnaires. The household questionnaire was answered by the head of the household and its objective was to characterize the household and family income. The individual questionnaire was answered by the older adults or their caregivers and contained questions about health matters, use of health services, lifestyle habits and behavioral characteristics. The interviews were carried out by household visits. The older adults were invited to take part in the study and those who agreed gave written, informed consent. Caregivers consented on behalf of disabled older adults.

Data were entered onto the electronic questionnaire, using tablets, through the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) mobile application10. Daily, after the interviews had ended, the data were transferred to an online server. The data were stored on the server, checked for inconsistencies and corrected when necessary.

The outcome analyzed in this study was functional dependence, assessed by the difficulty performing activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living. The data were collected using the Katz Index for Activities of Daily Living (ADL), and Lawton and Brody’s Scale for Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL)11,12. The ADL measure contained six items: dressing, bathing, eating, transferring, toileting and continence. The IADL measure contained eight items: handling small objects, handling finances, using the telephone, shopping, going to distant places, preparing food, housekeeping and handling medication. For each activity, three response options were selected: ‘receive no help’, ‘receive partial help’ or ‘receive full help’. Functional dependence in ADL and IADL was defined as a need for partial or total assistance in one or more activities.

The independent variables measured were sex (male or female), age (60–69, 70–79 or ≥80 years), schooling (none, 1–4 or ≥5 years), medical diagnosis of diabetes (no/yes), urinary incontinence (no/yes), history of stroke (no/yes), depression in the past year (no/yes), long term therapy (no/yes) and self-rated health (excellent/very good, regular or poor/very poor).

Descriptive analysis was used to estimate the prevalence of functional dependence in ADL and IADL and to describe the sample. Characteristics of the sample were described stratifying by sex using Fisher’s exact test. Crude and adjusted analysis was performed by Poisson regression with robust adjustment of variance. Prevalence ratios (PRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs) were reported. In the case of ordinal exposures, the Wald linear trend test p-value was reported, while the Wald heterogeneity test was used for the remaining variables.

The adjusted analysis followed a previously established hierarchical model with three levels. At the first level it included sex, age and schooling. Medical diagnosis of diabetes, urinary incontinence, history of stroke and depression in the past year were included on the second level. The third and final level comprised the variables long-term therapy and self-rated health. The variables were controlled for those on the same level and/or on preceding levels. Variables with p<0.20 were kept in the model in order to control for confounding factors. Variables with p<0.05 were considered associated with the outcomes.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Rio Grande under process 51/2017.

Results

It was found that there were 1131 older adults among the 1785 sampled households with eligible residents. Of this total (1131), 1029 took part in this study, corresponding to an 8.9% rate of losses and refusals. Non-response was predominantly due to unavailability after two repeated invitations.

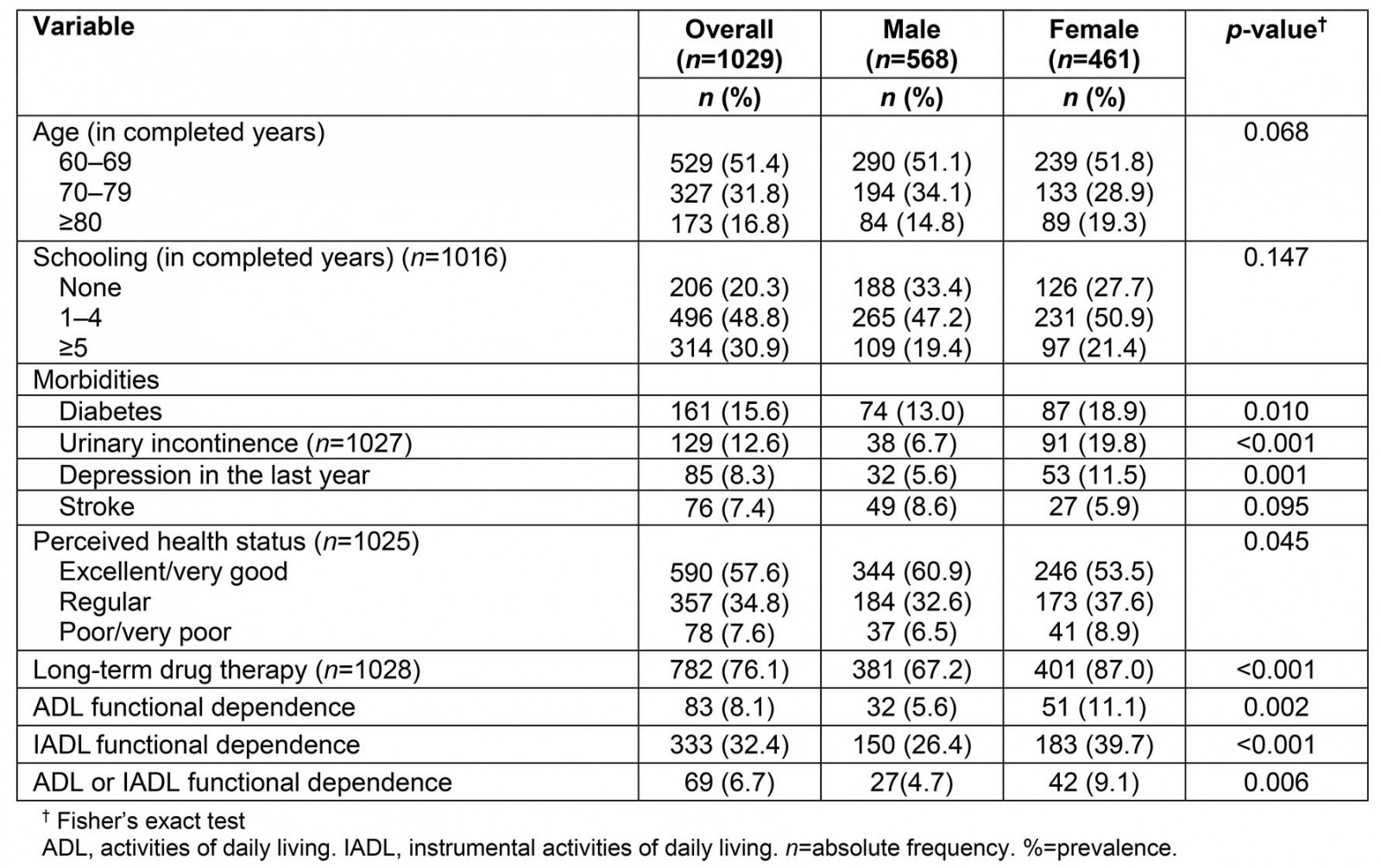

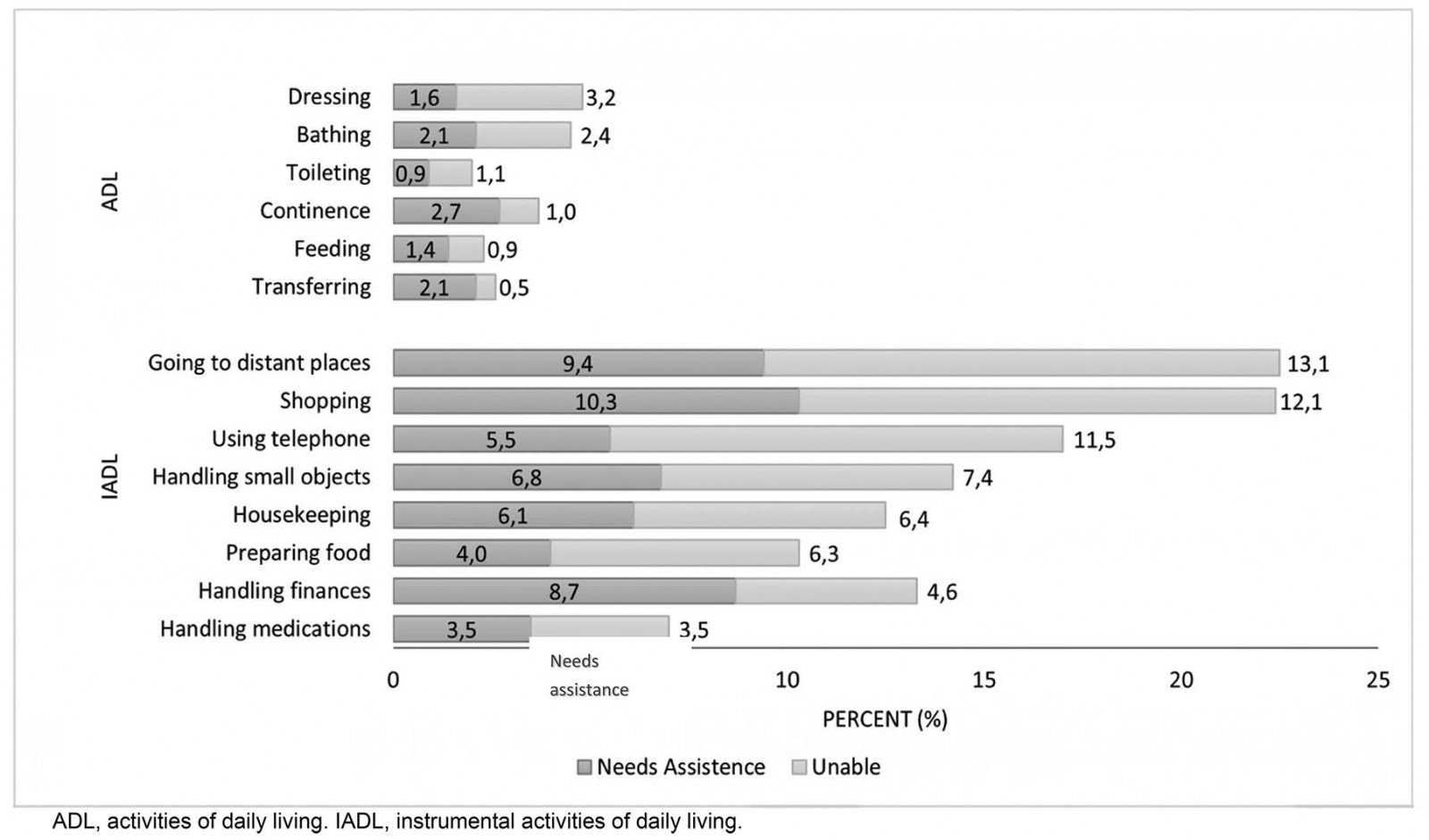

The mean age of the sample was 70.9±8.2 years (70.7±7.8 years for men and 71.1±8.5 for women; p=0.407) (data not shown). Almost 50% of the sample had 1–4 years of schooling. Women had a higher prevalence of diabetes, urinary incontinence, depression and continuous medication use. The overall prevalence of functional dependence in ADL corresponded to 8.1% (95%CI 6.4–9.7) and was higher in women (11.1%; 95%CI 8.2–13.9) than in men (5.6%; 95%CI 3.7–7.5). Overall care dependence in IADL was 32.4% (95%CI 29.5–35.2), being 26.4% (95%CI 22.8–30.0) and 39.7% (95%CI 35.2–44.2) for men and women, respectively. The occurrence of care dependence in one or more of ADL or IADL was 6.7% (95%CI 5.2–8.2) for the whole sample (Table 1). Bathing and dressing had a higher proportion of unable older adults among ADL. Going to distant places, using telephone and shopping were the main IADL with unable individuals (Fig1).

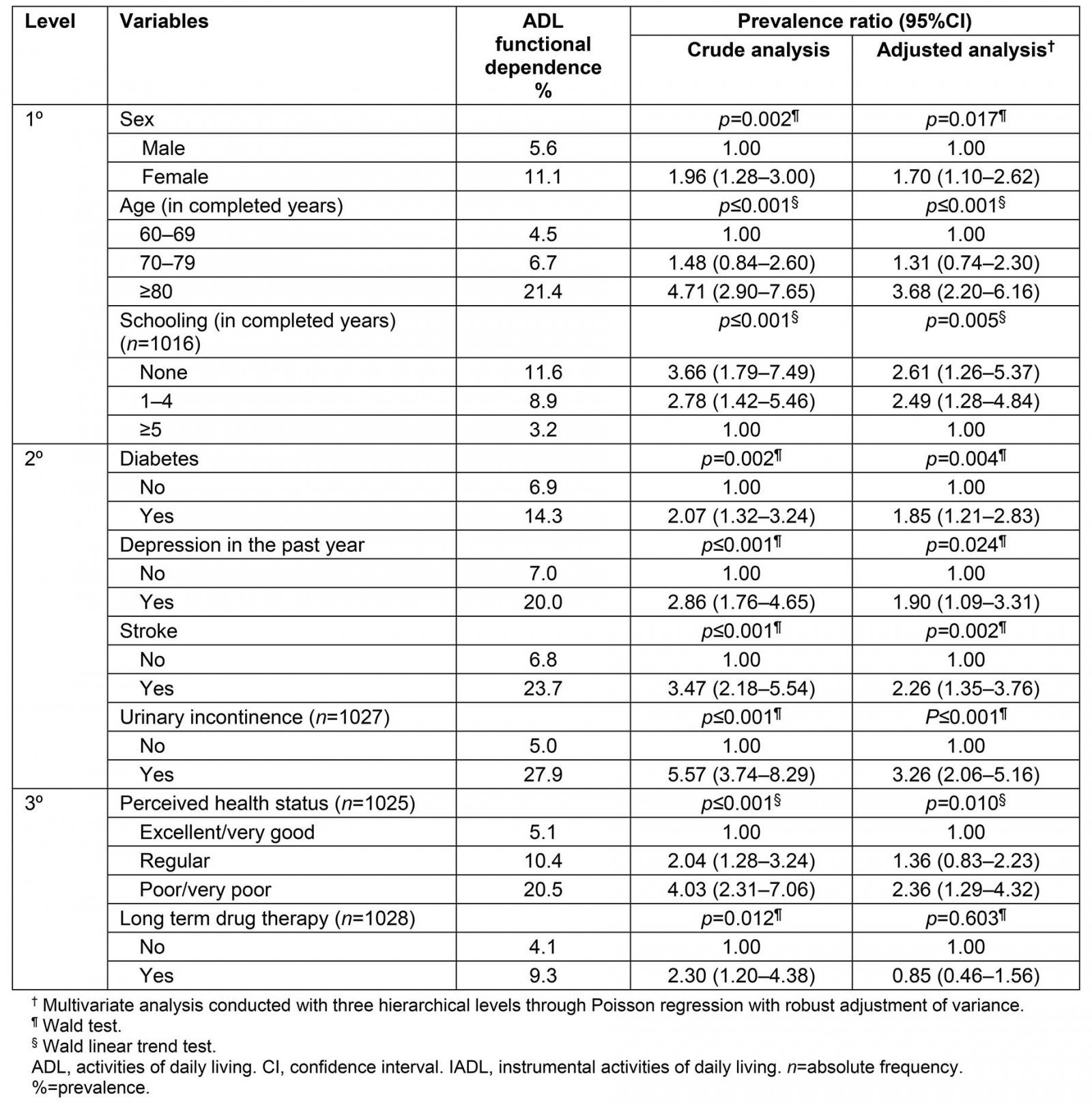

According to adjusted analysis, female sex (PR=1.70; 95%CI 1.10–2.62), age group 80 or over (PR=3.68; 95%CI 2.20–6.16), no schooling (PR=2.61; 95%CI 1.26–5.37) and 1–4 years of schooling (PR=2.49; 95%CI 1.28–4.84), having diabetes (PR=1.85; 95%CI 1.21–2.83), depression in the past year (PR=1.90; 95%CI 1.09–3.31), urinary incontinence (PR= 3.26; 95%CI 2.06–5.16), history of stroke (PR=2.26; 95%CI 1.35–3.76) and poor/very poor self-rated health (PR=2.36; 95%CI 1.29–4.32), were associated with functional dependence in ADL (Table 2).

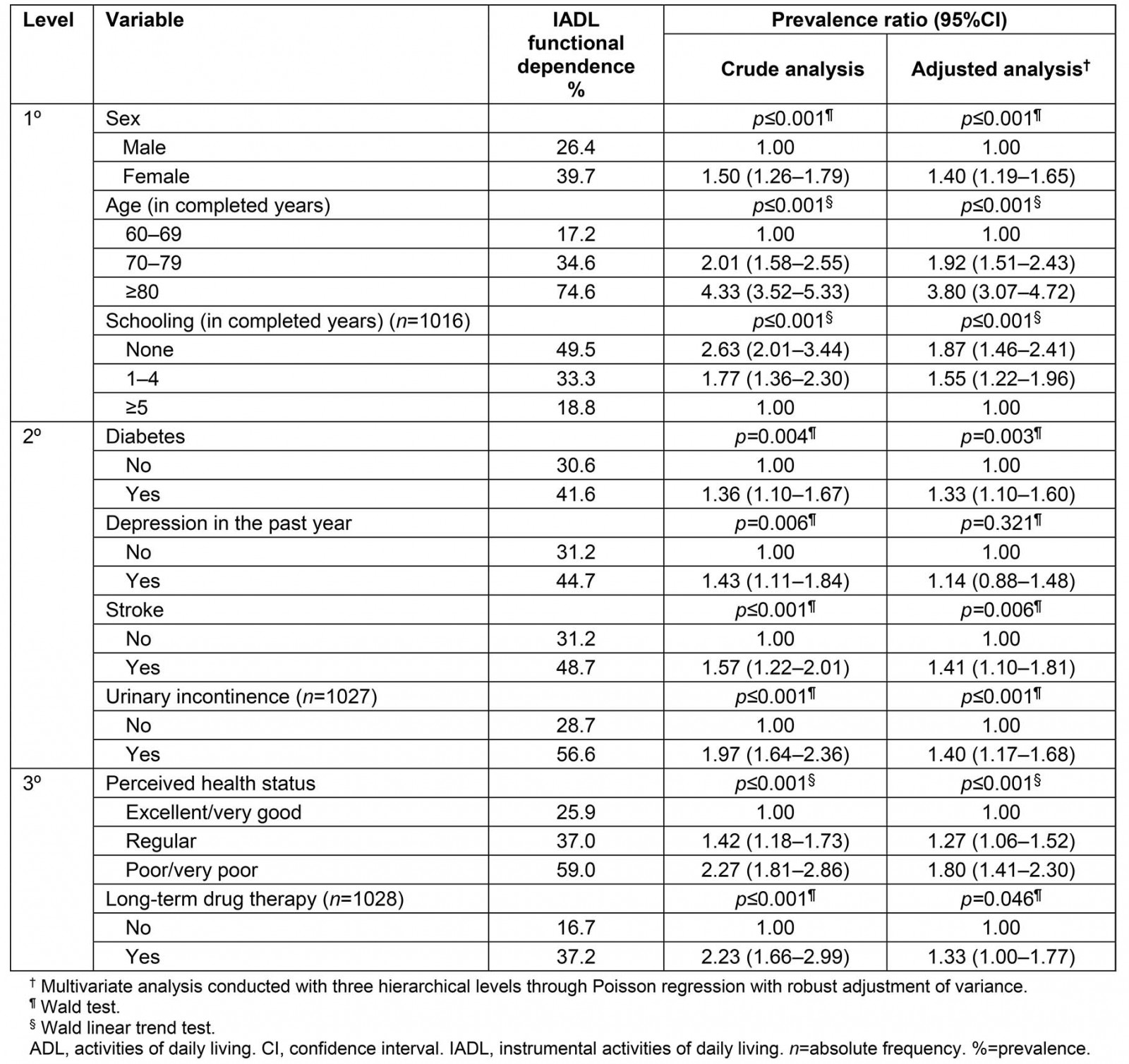

Significantly associated with functional dependence in IADL were female sex (PR= 1.40; 95%CI 1.19–1.65), the age ranges of 70–79 years (PR=1.92; 95%CI 1.51–2.43) and 80 or more years (PR=3.80; 95%CI 3.07–4.72), none and 1–4 years of schooling (PR=1.87; 95%CI 1.46–2.41), medical diagnosis of diabetes (PR=1.33; 95%CI 1.10–1.60), urinary incontinence (PR=1.40; 95%CI 1.17–1.68), history of stroke (PR=1.41; 95%CI 1.10–1.81) and regular or poor/very poor self-rated health (PR=1.80; 95%CI 1.41–2.30) (Table 3).

Table 1: Characteristics of the older adults in the rural area of Rio Grande, Rio Grande do Sul state, Brazil, 2017 (n=1029)

Table 2: Crude and adjusted analysis of factors associated with ADL functional dependence, Rio Grande, Brazil, 2017 (n=1029)

Table 3: Crude and adjusted analysis of factors associated with IADL functional dependence, Rio Grande, Brazil, 2017 (n=1029)

Figure 1: Level of dependence according to basic and instrumental activities of daily life, Rio Grande, Brazil, 2017 (n=1029).

Figure 1: Level of dependence according to basic and instrumental activities of daily life, Rio Grande, Brazil, 2017 (n=1029).

Discussion

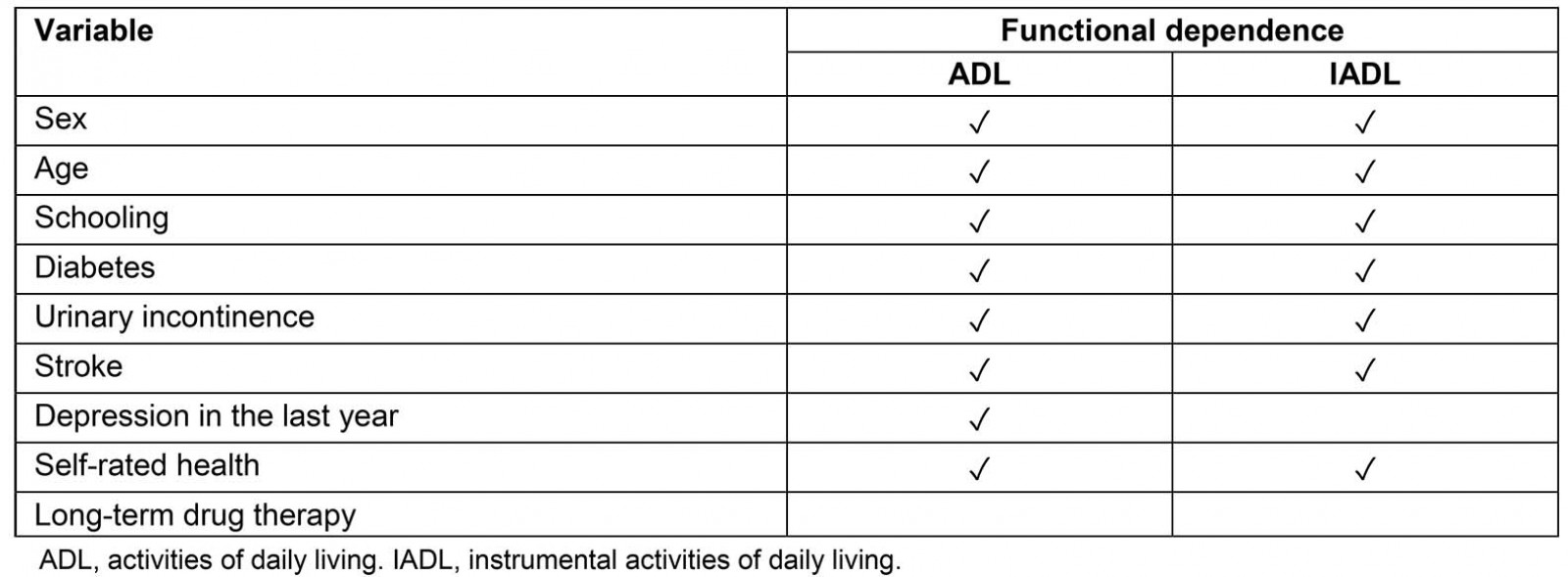

In this study, one in every three and one in twelve older adults were affected by functional dependence in IADL and ADL, respectively. Being female, older, having less schooling, diabetes, urinary incontinence, stroke and poor/very poor self-rated health were independently associated with both outcomes. Depression in the previous year remained associated only with functional dependence in ADL (Table 4).

There is considerable divergence in the prevalence of functional dependence reported in rural community-based studies, with values ranging from 2.3% in China13 to 59.3% in India14. The prevalence of functional dependence in ADL and IADL found in this study was lower when compared to most previous surveys. For example, in rural areas of south-eastern Poland, the prevalence of functional dependence was 36.8% in ADL and 43.2% in IADL15. Another study carried out in a rural area of West Bengal found that 32.5% of older adults had functional dependence in ADL and 59.3% in IADL14. All of these studies assessed the functional dependence with Katz and Lawton instruments. The proportion of females was higher in the Chinese and Polish studies (60%) and comparable to the present study’s findings in the Indian study (42%). Thus, the proportion of females does not explain a lower or higher prevalence of functional dependence in ADL or IADL. Characteristics such as age group, comorbidities and self-rated health, which vary between different populations, may partially justify the differences in the prevalence of functional dependence in the literature.

In Brazil, in the rural area of Pelotas, a neighboring city 50 km away from Rio Grande, the prevalence rates for functional dependence in ADL (18.2%) and IADL (45.4%) were higher than in the present study’s findings16. However, in the urban area of Bagé, 240 km away from Rio Grande, ADL and IADL functional dependence prevalence rates were similar: 10.6% and 34.2%, respectively17. Differences in the prevalence of functional dependence between Pelotas and Rio Grande/Bagé are difficult to explain. First, both Pelotas and Bagé samples were 60% female. Second, the age structure and the prevalence of common chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes and osteoporosis are similar in the three municipalities. Unmeasured characteristics may be underestimating the prevalence found in Rio Grande in comparison to Pelotas. However, the authors cannot rule out that the rural elderly people of Rio Grande may have less functional dependence than those in Pelotas.

According to the literature, older women are more susceptible to functional dependence than men4,18,19. This association is generally explained by the greater longevity of women20. However, the present study found only a slightly higher proportion of women than men in the older group (age 80 or more years). Moreover, sex and age were adjusted simultaneously in the model and both were independently associated with functional dependence in ADL and IADL. Women usually have a higher prevalence of comorbidities in epidemiological studies than men in different age groups. Furthermore, comorbidities are probably mediating variables between the effect of sex (females) on functional dependence. Also, women report physical dependence more easily than men, who may omit their symptoms due to cultural gender differences.

Older individuals were more likely to have functional dependence in basic and instrumental activities of daily life, and this association has been described in several studies14,15. This can be explained because the ability to perform a task involves the integration of physiological systems, which gradually deteriorates with ageing21.

Similar to the findings of national17,22 and international surveys4,14,15, schooling had an important effect on the prevalence of functional dependence in ADL and IADL. Individuals with more schooling have a better understanding of guidance on health and self-care; furthermore, they tend to have better living and working conditions and, consequently, their aging process may be healthier than those with little schooling23.

Diabetes, urinary incontinence and stroke were associated with the increasing probability of functional dependence in ADL and IADL, which is consistent with the literature18,19. The mechanism by which diabetes leads to functional dependence is still unclear. A possible explanation would be that complications related to diabetes, especially vascular and neuropathic, associated with coexisting morbidities, could be a potential mediating factor in the relationship between diabetes and functional dependence24.

Having had a stroke at some time in life and urinary incontinence were the morbidities most strongly associated with both ADL and IADL functional dependence. Considered to be one of the leading causes of long-term functional dependence in adult life, stroke has a direct impact on motor and sensory functions related to movement and balance, as well as urinary and fecal incontinence25. Thus, urinary incontinence and functional dependence may be chronic conditions resulting from more distant morbidities such as diabetes26.

Other studies have already identified the association of depression and functional dependence14,15. This association results from the fact that symptoms of depression such as fatigue, tiredness and malaise compromise the performance of activities related to self-care27. Inability to perform basic functions may also lead to depression28. Therefore, it is not possible to establish a causal relationship of the association found.

Regarding self-rated health, two longitudinal studies conducted in the Netherlands29 and the UK30 have reported poor self-rated health as a risk factor for functional dependence in older adults. In Brazil, a cross-sectional study based on data from the 2003 PNAD (Brazilian National Household Survey) found an association between self-rated health and functional dependence22. This finding is probably justified by the fact that the negative self-perception of health is strongly related to the presence of morbidities and other conditions that determine functional dependence31,32. However, there may be reverse causality, given that functional dependence in ADL and IADL can have a negative impact on self-rated health.

Some limitations of this study must be highlighted. Cross-sectional design prevented a temporal relationship for the associations between depression and self-rated health with the outcomes. Another limitation was the exclusion of institutionalized older adults, which may have contributed to the lower prevalence of the outcomes. However, the authors did not exclude individuals who were unable to answer the questionnaire. Instead, caregivers were interviewed.

Despite similar studies in rural Pelotas and in an urban area of Bagé, in Rio Grande functional dependence among older adults living in distant localities, such as those from the islands Ilha dos Marinheiros and Ilha da Torotama, as well as Capilha Beach, is described. The majority of the individuals are Azorean descendants and worked on fishing and/or vegetable planting. In the Pelotas rural area, most individuals are Pomeranian descendants and worked on tobacco and peach crops.

The sampling method resulted in a representative sample of rural older adults in Rio Grande. There were 1351 individuals (≥60 years) in the study ‘Health of the rural population of Rio Grande’, which is higher than the 1020 individuals reported by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics in the 2010 census33. It is reasonable to assume that the number of older adults in the rural Rio Grande increased from 2010 to 2017. Besides the ageing of this rural population, the increase might be related to the migration of retired older individuals from urban to rural areas.

Table 4: Variables included in the hierarchical analysis model showing association with daily living activity functional dependence in the adjusted analysis, Rio Grande, state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, 2017 (n=1029)

Conclusion

There is a high prevalence of functional dependence among rural elderly people in Rio Grande. In the context of the Brazilian economic crisis and health budget restrictions that affect the coverage of the Family Health Strategy, knowledge about functional dependence in far and remote populations is relevant to ensure access to health services and to reduce health inequities. Functional dependence in rural areas can be even worse than in the urban context. The lack of infrastructure, architectural barriers, loneliness and social isolation are characteristics that may exacerbate physical limitations and accelerate the deterioration of the health of older adults. Based on the present study’s findings, family health teams can identify individuals at higher risk of functional dependence and propose strategies to prevent or postpone decline in functional capacity.

Acknowledgements

This project received support from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development through a research productivity scholarship, as well as from the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Level Personnel/Ministry of Education and from Pastoral da Criança.