Introduction

Delivering health services and improving the health outcomes of the 1.3 million people residing in northern Australia, a region spanning 3 million km2, presents specific challenges. Northern populations experience poorer health outcomes than their southern counterparts across a range of measures including life expectancy, potentially preventable hospitalisations, avoidable deaths, and risk factors for chronic disease1-3. Many entities, including public, private, community controlled and other non-government organisations, are responsible for planning and delivery of health services across the north. Training and retaining a fit-for-purpose, competent health workforce is also a major focus of the region’s governments, universities, health services and training organisations but, as in rural and remote areas in Australia generally, workforce shortages across the north are widespread4.

With around 40% of the northern Australian population living in townships and communities of less than 8000 people, health service capacity, including workforce, is widely distributed5. Outside of the larger regional centres of Cairns, Darwin, Mackay and Townsville, which offer a full range of primary healthcare, secondary and most tertiary services close to home, patients access visiting or on-site primary care services including Aboriginal community controlled health services (ACCHSs) and referral pathways often involving travel or e-health for specialist and allied health services. Larger towns also offer small public hospitals and clinics. Other subcontexts of health service delivery in the north include discrete Aboriginal, and Torres Strait Islander, communities; and population centres with high numbers of fly-in/fly out or drive-in/drive-out workers, such as mining towns. Around 15% of the northern Australian population identify as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander, representing 30% of all Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders in Australia6.

The 2015 Australian Government’s Northern Australia White Paper articulates an opportunity for northern Australia to ‘become an economic powerhouse’ within Australia, identifying health as a key strategic pillar in developing the north6,7. Northern Australia, as defined in the White Paper, incorporates all of the Northern Territory (NT) and the northern parts of Queensland and Western Australia (WA) above the Tropic of Capricorn6 (Fig1). Across the north, health care and social assistance is the largest employing industry, representing 13% of total employment7. Improving health services, including health workforce, in the north is fundamental to both the wellbeing of people living in the region and broader economic productivity and development.

Health services are the most obvious output of health systems but rely on many other health system components or ‘building blocks’ including financing, governance and leadership, human resources for health (ie health workforce), medical technologies and health information systems8. Although many articles and policy papers address aspects of these different components in northern Australia (as identified in this review), few (if any) take a systems level approach, integrating and analysing the way these various components interact and cumulatively influence the coverage, quality and responsiveness of health services in the region. The aim of this review is therefore to systematically review the available published literature (both peer-reviewed and grey literature) describing health service delivery and health workforce characteristics, trends, challenges and opportunities across northern Australia and to identify key policy-relevant gaps. The review constitutes the first component of a broader project commissioned by the Cooperative Research Centre for Developing Northern Australia to develop a Northern Australia Health Service Delivery Situational Analysis9.

Figure 1: Geographic boundary of northern Australia as defined in the review (all of the Northern Territory, along with Queensland and Western Australia above the Tropic of Capricorn).

Figure 1: Geographic boundary of northern Australia as defined in the review (all of the Northern Territory, along with Queensland and Western Australia above the Tropic of Capricorn).

Methods

Design

Scoping reviews enable complex and heterogeneous bodies of literature in a field to be summarised and mapped in terms of volume, nature, characteristics, extent and gaps10. This literature review adopted a scoping review design11 utilising systematic methods to comprehensively identify and map the literature relating to health service delivery and workforce in northern Australia. The searching, selection and extraction methods followed the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews Checklist12.

Search strategy

Both peer-reviewed and grey literature were sourced for the review with searches for both types undertaken in parallel by two members of the project team during August 2019.

Grey literature searches: Given the focus of the review on identifying policy-relevant health systems literature and gaps, grey literature such as strategy documents, annual reports and policy papers were identified as important sources of information. Searches involved website searching, contacting policy experts for advice on key articles and websites, and snowballing from references. Documents were sourced from organisational websites, including government health services and planning bodies, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health organisations, universities and research institutes. Searches for policy and health system strategy documents were conducted by jurisdiction (ie by state and territory) and, where available, across jurisdictions.

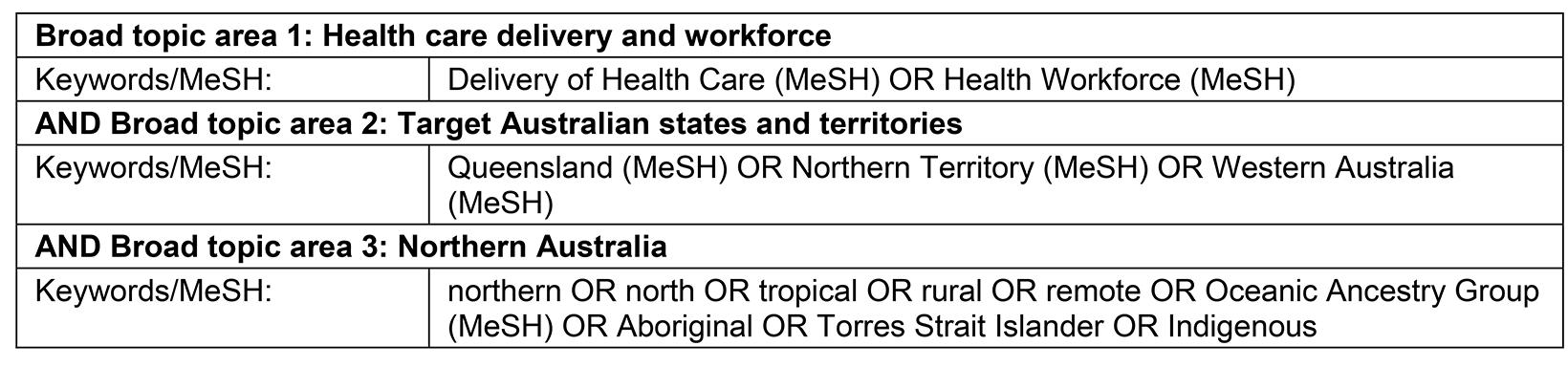

Electronic database searches: Peer-reviewed publications were identified from electronic database searches, reference lists and expert recommendations. An initial list of keywords was developed to reflect the review aim, and searches using these terms were piloted in Scopus and Medline (Ovid). Final search terms were selected to ensure an appropriate balance of breadth and specificity. The final search strategy as used in Medline (Ovid) is shown in Table 1. Final electronic searches were conducted in Scopus, Medline (Ovid), CINAHL, ERIC and Informit (Health and Indigenous suites); these databases were selected for comprehensiveness and likelihood of containing policy-relevant information appropriate to the Australian context. Searches in Medline (Ovid) and CINAHL used medical subject headings (MeSH) and keywords, while searches in the other databases relied on keywords.

Table 1: Search strategy and keywords in Medline (Ovid)

Selection and extraction

Selection and extraction were undertaken in parallel by the two members of the research team who undertook the grey literature and database searches. This process involved frequent meetings between the two researchers to agree on an approach to interpreting the inclusion criteria and determining eligibility, supplemented by regular meetings of the broader review team to discuss the boundaries and address any concerns. Stakeholders involved in the broader Situational Analysis project were also consulted about the approach to searching, selection and extraction in the review. Articles were included if they were published in English and described characteristics, trends, challenges or opportunities relevant to health service delivery and workforce in northern Australia. Although a relatively narrow date range of 2015–2019 was used in the database searches to maximise policy currency of the research-based findings, the search strategy enabled flexibility to include seminal documents and resources published prior to 2015 as identified through snowballing, expert recommendation and grey literature searches. Three jurisdictional advisory groups involving senior health system stakeholders in each jurisdiction, which were convened for the broader Situational Analysis project, were an important source of advice for additional literature. Following screening of title-abstract records from the database searches, full texts of peer-reviewed literature were uploaded to Clarivate EndNote and assessed for eligibility. While there were no uncertainties about inclusion of any grey literature sources, uncertainty about whether 29 peer-reviewed articles met the inclusion criteria was resolved by consensus involving at least three reviewers.

Information from peer-reviewed and grey literature was extracted to a single data extraction template in Microsoft Excel using the following fields: authors/organisation; title; date of publication; study setting/geographic location; study type; study design/type of evidence; focus, aim and rationale of the study; current capacity; developmental trends; key challenges; key opportunities; and gaps. Additional fields were added to enable examination of whether articles mentioned community participation and, if so, how any participatory planning was operationalised; these fields facilitated critical examination of the body of literature using a community engagement lens. A broad interpretation of community engagement was used for this purpose, which allowed the reviewers to identify whether researchers or policymakers had sought to engage end users of the research or policy (whether community members directly, clinicians in a target health service or representative organisations) in the development of the publication, and how such engagement was enacted. Information relating to the social determinants of health was also extracted (either as reported in the article or reflecting analysis by the authors of this review). Finally, records were classified using a health systems framework (described below) to facilitate analysis of the highly diverse body of literature.

Synthesis

Relevant data from the articles included quantitative and qualitative data, and findings were synthesised and reported in narrative form, using a narrative synthesis approach13 to facilitate mapping of the domains covered by the literature. This synthesis focused primarily on identification of key issues and gaps, with quantitative findings extracted where possible to supplement findings relating to health service delivery, and workforce capacity and trends. Consistent with a scoping review approach and the review aim, selected articles were not critically appraised for methodological rigour; however, mapping of the study types enabled the review to report the extent and nature of the empirical body of evidence underpinning the findings.

Findings were analysed and reported against the WHO health system ‘building blocks’8: service delivery, health workforce, health information systems, access to essential medicines and technologies, financing, and leadership and governance. As is sometimes done internationally when using the building blocks, a seventh category – community engagement – was added to capture and describe community-focused issues and gaps. The WHO building blocks are interconnected components that contribute to the functioning of health systems.

Results

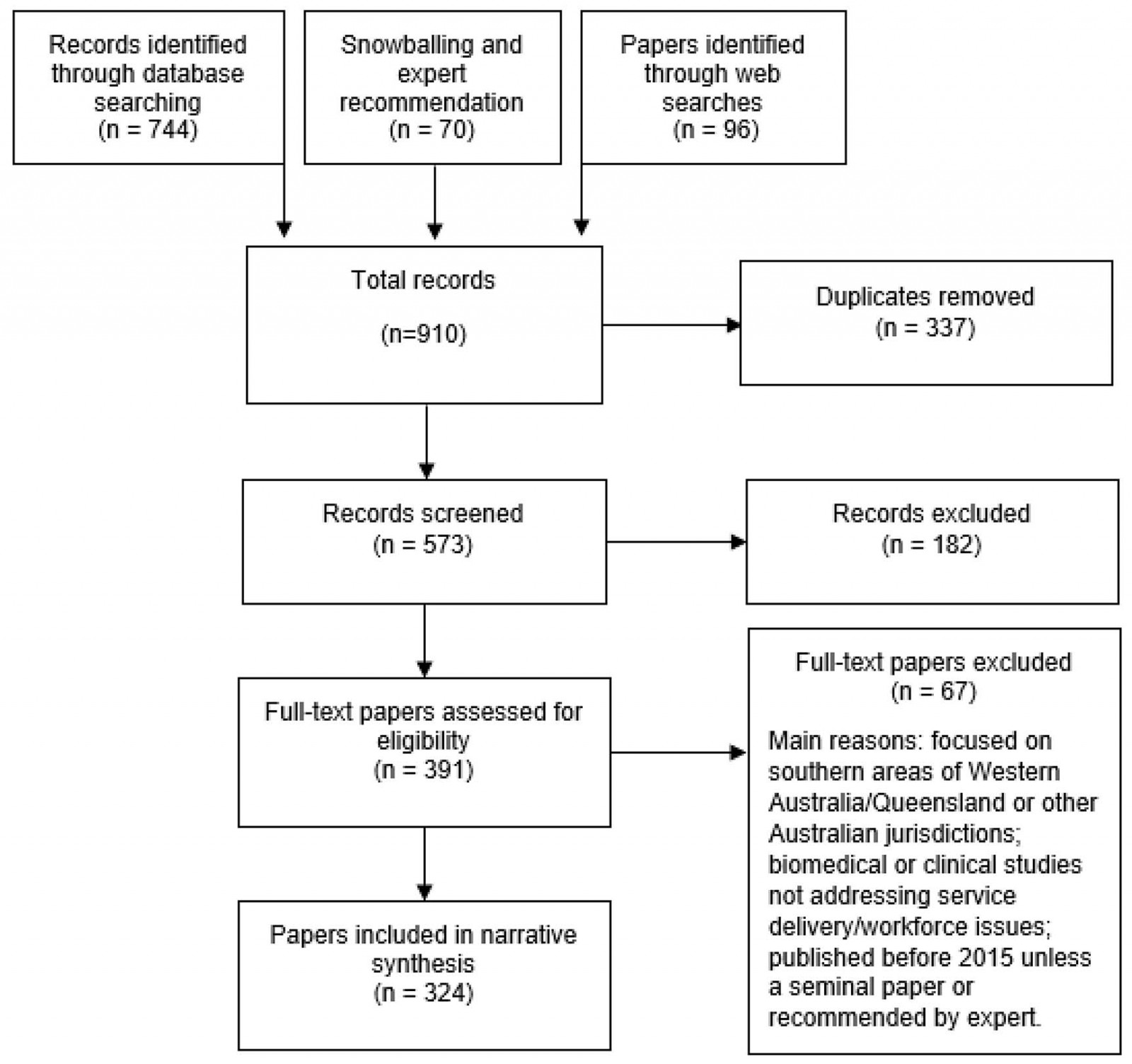

From a total of 324 documents and data sources included in the review following screening and eligibility assessment (Fig2), 197 were identified as peer-reviewed journal articles and 127 as policy papers and data sources (grey literature). The grey literature synthesis reflects the strategic efforts of key health service delivery and workforce planning bodies in northern Australia, and includes policy strategies, plans and reports including budgets, health profiles and datasets. The peer-reviewed literature (referred to from here as articles) consists of empirical research (88%), expert opinion (10%) and other literature reviews (2%). Most articles focus on the jurisdictions of Queensland (39%) and the NT (35%), with fewer articles focused on WA (17%) or on cross-jurisdictional issues (10%). Grey literature has roughly equal focus on the NT (31%) and cross-jurisdictional issues (30%), with fewer sources focused on Queensland (23%) or WA (17%). Key findings are presented against the six WHO building blocks and the community engagement addition.

Figure 2: PRISMA flow diagram, showing results of literature searches.

Figure 2: PRISMA flow diagram, showing results of literature searches.

Leadership and governance

The innumerable organisations providing healthcare and workforce education and training across the north have largely separate governance and resourcing structures, with clear distinction between jurisdictions. Though uncommon, there are a few notable examples of cross-northern governance arrangements focusing on coordination and information-sharing relating to health services and workforce planning and delivery. An example of cross-jurisdictional collaboration is the clinical use of remote primary healthcare manuals in the NT and northern WA14. While research initiatives sometimes involve project-specific governance arrangements involving academic, health service and community stakeholders across jurisdictions15,16, the only cross-jurisdictional initiative identified at a broad health policy level is the (now disestablished) Greater Northern Australian Regional Training Network (GNARTN). GNARTN was established in 2013 to address a range of clinical workforce and clinical placement, education and training issues, via an agreement reached between WA, NT and Queensland health departments, supported with Commonwealth funding17. GNARTN aimed to address a lack of ‘governance connectivity’ across the northern jurisdictions, with stated achievements including improvements to health service efficiency and effectiveness, building of new capabilities, reduced duplication and identification of shared opportunities for new initiatives17.

Even within jurisdictions, several articles identify fragmentation of health-related policy and planning as an important governance challenge18-20, with some articles offering specific examples of how policy and planning fragmentation result in service fragmentation, impeding optimal health service delivery. One study found that a key challenge for NT-based health professionals providing postpartum diabetes care to Aboriginal, and Torres Strait Islander, women was disjointed systems and confusion about roles and responsibilities, highlighting a need for improved communication and integration of different health system components21. Another study demonstrated that poor coordination of services inhibited support systems for people travelling to large regional centres from remote far north Queensland to access health care19.

Primary health networks (PHNs), four of which are in northern Australia, were established nationally to address fragmentation resulting from different funding streams and siloed engagement between different organisations22-24. The PHN roles are intended to involve a commissioning cycle of planning, determining need and innovative solutions, procuring services and monitoring and evaluation, drawing from comprehensive needs assessments. However, no northern-focused studies evaluated the PHN model or the establishment of devolved health services districts or networks such as Queensland’s Hospital and Health Services. In general, few articles offer an analysis of the complex governance structures or policy approaches apparent across the north, apart from articles expressing strong support for community governance models in the ACCHS sector (see ‘Community engagement’). Nonetheless, some articles have a macro policy focus; examples include an evaluation of Connecting Healthcare in Communities, a historical initiative in Queensland aimed at establishing formal partnerships in the primary healthcare sector to improve health care and outcomes25, and a study examining the effect of changes in primary health care in the NT over 5 years (2009–2013) on services’ ability to respond to health inequity26. This latter study found that long-term secure funding is needed to support delivery of comprehensive primary health care, which underpins equity performance. Perhaps linked to the relative lack of policy analyses, very few studies addressed issues pertaining to policy leadership, although community leadership was an implicit focus in the literature on ACCHSs (see ‘Community engagement’). Articles for only two studies directly mention leadership in relation to study findings, with one identifying a general need for strengthened Aboriginal leadership as part of health system reform in the NT27, and the other identifying gaps in formal recognition and training of Indigenous health workers as program leaders in Queensland28.

Community engagement

Community engagement in the literature represents a continuum of approaches from passive feedback platforms to active community control of health governance structures. Most strategic plans and policies of northern organisations – including the PHNs, government health services and universities – express an intent to engage with individuals and communities through management mechanisms, governance models, service delivery or ‘consumer’ feedback processes. The grey literature also demonstrates an aspiration for health services to be delivered in a way that values and respects cultural rights, views and values of Aboriginal, and Torres Strait Islander, people across the north22. Jurisdiction-based frameworks, such as the NT Aboriginal Cultural Security Framework 2016–202629, aim to guide the work of government services providing culturally secure health care.

Notwithstanding these aspirational sentiments, the tangible role or mechanisms to engage with community members as agents of health governance is poorly reflected in the grey literature, with the notable exception being the ACCHS sector. The ACCHS model of health service delivery is described as an exemplar in community engagement, adopting a healthcare approach that values culture, spirit, country, family, community and language as critical determinants of physical, social and emotional health and wellbeing of Aboriginal, and Torres Strait Islander, people26,30-33. Community engagement approaches in other organisations sometimes involve partnerships with ACCHSs and ACCHS peak bodies within the jurisdictions. The Western Queensland PHN, for example, has a partnership with the Queensland Aboriginal and Islander Health Council and individual ACCHSs to ‘enable greater quality and capability of services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in the catchment’34.

Numerous articles reviewed highlight the comparative strengths of ACCHSs in responding to population health inequities and in providing a comprehensive model of primary health care26,35-40. Further, ACCHS peak bodies across the three northern jurisdictions were noted to provide a strong voice for Aboriginal, and Torres Strait Islander, people in regional service delivery, research and policy. For example, the Kimberley Aboriginal Medical Services Council and the Kimberley Aboriginal Health Planning Forum lead the longstanding production of the Kimberley Chronic Disease Protocols, the Kimberley Maternal and Child Health Protocols and the Kimberley Standard Drug List41. However, tensions were identified in the literature between cultural preferences and biomedical models of health care in the north, such as in the use of practice manuals relying predominantly on scientific and clinical logic (rather than community choices) to sanction birthplace42, in maternity services policy that effectively ‘silence’ the voices of Aboriginal Australians43, and in community-disengaged policies on end-of-life care for remote-dwelling Aboriginal people44,45.

Financing

The grey literature highlights growing cost pressures facing the northern Australian health system regarding the high chronic disease burden, ageing population, and the need to maintain ageing infrastructure and upgrade information and communications technology infrastructure46-51. Reflecting the higher disease burden and costs in the north, data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare indicate higher per-capita spending on health in parts of northern Australia compared with national averages: in 2017–2018, the average per-capita spending on health in the NT was A$10,857 per person compared with A$7485 per person nationally52. According to Zhao et al53, in the NT alone the excess costs associated with the Aboriginal health gap were A$16.7 billion over a 5-year period (made up 22% of excess healthcare costs, 35% due to lost productivity and 43% attributable to lost life-years). The high chronic disease burden across the north is reported as a leading driver of escalating costs48,54.

A large body of evidence in the review supports strengthening comprehensive primary health care as one of the most effective strategies for improving health outcomes and containing healthcare costs54-59. An important distinction is made in the literature between fee-for-service ‘walk in/walk out’ models of general practitioner-led primary care (as exemplified by the Medicare Benefits Schedule financing structure), and the strategic intent of resource allocation for population-based ‘comprehensive’ primary healthcare models (as implemented in ACCHS)60. A rationale is also offered for transitioning to models of funding for remote primary healthcare services that include the safety and equity requirements for a ‘minimum viable service’, requiring payment reforms that reward value over volume of services55. In the NT, Wakerman et al55 found that the current funding systems for remote primary healthcare services, including Medicare, do not promote equity in access, warranting establishment of a minimum funding base for primary healthcare services in remote communities, supplemented by a capitation rate. Such reforms may be in the pipeline – the Australian Healthcare and Hospitals Association, in its blueprint for the next 10 years in the health sector, reported developing a mixed funding formula for the health sector whereby 25% of resource allocation is outcomes-based, and is initially trialled for the top four chronic diseases, risk factors or determinants of health61.

Service delivery

A wide range of health services and models in northern Australia are described in the literature. Examples include hospital services58,62; remote primary care clinics57,63; ACCHSs26,35,36,64; rehabilitation, cancer, dialysis and palliative care services65-69; visiting specialty, general practitioner and nurse-led remote area outreach clinics70-72; maternal and child health services73,74; mental health and social services75-77; health promotion services64,78,79; oral health services80-84; and e-health services (see ‘Essential medicines and technologies’). Most articles were about improving access to the various healthcare services outside of larger regional centres and highlight a range of persisting barriers. These barriers include:

- contextual factors such as small population sizes and remoteness, meaning great distances between communities and services18,85

- workforce shortages, especially in remote and very remote areas (see ‘Health workforce’)

- deficiencies in providers’ cultural capability training and/or the ability of service models to deliver their cultural capability goals86.

Most of these articles relate specifically to rural and remote health service delivery, with few addressing health service issues in the larger regional centres. In addition, apart from the articles relating to mental health and social services already cited, mental health issues in the north appear to be under-prioritised and under-explored in both the policy and peer-reviewed literature.

Key enablers of successful health service models and programs include:

- use of innovative workforce models87-89

- cross-sectoral collaboration between health services and non-health organisations90

- community leadership and involvement in program design and implementation36,72,91

- a focus on complex healthcare needs rather than disease-specific care67,92

- continuity of care, including services close to home93

- effective cross-cultural communication16,86,94-99.

Several articles address investment need in primary prevention, with many of the reported studies demonstrating significant health benefits from such investments64,79,96,100-105. For example, McMullen et al106 link environmental risks with health service use in northern WA, finding that around 20% of attendances at primary care facilities are directly attributable to the environment, indicating that investments in environmental factors such as sanitation and hygiene, home condition, land use, air pollution and chemical exposure could substantially reduce healthcare demand. The ability of comprehensive primary healthcare models to combine competent clinical care with population health programs underscore its relevance to rural and remote contexts in improving health care and outcomes38,107, often at reduced costs (see ‘Financing’).

Strategic planning documents of the government services express strong commitments to equitable health outcomes, prevention of poor health and supporting people to lead healthier lives46,48,108-110. However, some of the jurisdictional health budgets and implementation documents analysed in the review indicate limited translation of strategic intent to act on social determinants of health at a strategic planning level into operational capacity and funded action111-113. In WA, a review of the health system recommends reforms involving a cultural shift from acute, reactive, hospital-based systems to systems focused on prevention and equity114. As noted earlier, articles for several studies report the importance of addressing the social, cultural and environmental determinants of health that underpin health outcomes. For example, studies across the north identified a need for increased attention to and investment in nutrition, including food access and affordability115,116; physical activity96,117; adequate hygiene and housing58,118; tobacco control102,119; alcohol policy105,120,121; child literacy101; health literacy122; socioeconomic circumstances including employment and income122,123; and caring for country124.

Health workforce

The literature documents many ongoing challenges across northern Australia in recruitment and retention of health workforce. All three jurisdictions report shortages of health workforce, particularly of medical generalists and specialists, and allied health workforce, in rural and remote areas125-128. Some articles report very high turnover of nurses and allied health professionals in government-funded remote NT clinics and heavy reliance on agency nurses129-131. For example, a study conducted in the Top End region of NT found that only 20% of nurses and allied health professionals remained working at the same remote clinic 12 months after commencing, with half leaving within 4 months129. Low levels of doctor retention have also been documented in WA, with Bailey et al132 finding that the majority of new doctors leave rural practice within 5 years of their posting.

A synthesis of studies on health workforce retention applied to the NT context describes potential savings to the NT health system of around $32 million per annum if staff turnover in remote clinics was halved131. The present study finds considerable evidence about what works in improving health workforce retention but describes a persistent implementation gap in translating empirical research evidence into policy action. Addressing this gap requires political commitment, and coordination and collaboration between different organisations and sectors.

Under-representation of Aboriginal, and Torres Strait Islander, people in the health workforce is also reported; for example, in the WA Country Health Service catchment, 10% of the population identify as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, but only 4.4% of health sector employees identify as such, although a range of strategies are being employed to increase recruitment and retention and to support Indigenous leadership development133. Articles for several studies examine the role and/or training pathways of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workers and Health Practitioners89,123,134,135, finding the roles to be highly effective but potentially hampered by significant unmet training needs. While availability of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workers and Health Practitioners is described as instrumental to culturally safe health service delivery, this cadre of health workforce is seen to be under-recognised, under-supported and under-utilised136.

Training needs are also reported across a wide range of capability areas for different health professional staff, including in provision of culturally safe care among hospital staff in the NT135, health promotion skill development for primary healthcare staff working in Cape York104, and research skills among regional allied health professionals from the northern districts of Queensland Health137. Articles for several studies profile successful models of undergraduate medical and rural generalist training to develop a fit-for-purpose rural medical workforce, which are currently being used in the north138-145. These highlight the importance of exposing undergraduate students to all elements of the rural training pathway, including well-supported rural clinical placements, to build the rural and remote workforce. Apart from a study evaluating allied health assistant roles in the NT88, however, no articles report studies on the development or evaluation of rural generalist training pathways in allied health, nursing or pharmacy. Trainee and staff support and wellbeing, including occupational health and safety, are also important considerations in building and supporting health workforce across the north, particularly for those working remote and very remote locations146-148.

Health information systems

The grey literature indicates increasing uptake of digital information systems in healthcare settings in the north47,49. Improved data sharing is also reported as an opportunity for improving the quality and coordination of patient care23,149. In Queensland, investments totalling more than $1 billion are estimated to be needed to upgrade ageing information and communication infrastructure in the health sector, to deliver a range of priorities including contemporary network and data centre foundations, information interoperability, statewide electronic medical records and secure information-sharing environments49.

Despite the policy attention on digital information systems and infrastructure across the north, few evaluations of health information systems were identified in the literature. One study evaluating an electronic data management system implemented in the delivery of health services to the Fitzroy Valley in WA (Communicare) found the system to be a feasible way to establish population health indices for the remote health service with minimal expenditure150. Another study evaluated the Chronic Conditions Management Model in the NT, involving monthly functional recall lists, quarterly functional traffic light reports of performance and 6-month trends reports151, finding that the model leads to substantial improvements in preventive care for cardiovascular disease in the primary healthcare context. Additionally, another study identifies the lack of connectivity between patient information systems in different services as a key challenge in implementing a diabetes antenatal care and education clinic in the remote NT18. Future evaluative work should explore the benefits and shortcomings of different digital health information systems being rolled out across the north, including implementation experiences.

Essential medicines and technologies

The literature in this building block addresses both access to medicines and the role of technological innovations in improving health care, particularly among rural and remote patients. Several articles report barriers to treatment access, such as low levels of health literacy among patients with poorly controlled diabetes, and difficulties accessing reimbursement for hepatitis B treatment, in the Torres Strait region70,152; and deficits in registration and recall systems for rheumatic heart disease treatment in northern Queensland153. A statewide initiative in Queensland that aims to improve access to medicines and pharmaceutical advice among Aboriginal, and Torres Strait Islander, people is also reported154. Although not examined directly in the literature, nationwide funding mechanisms such as the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme also support medicines access in the north.

There is increasing emphasis on the benefits of digital and telehealth models of care in northern jurisdictions47,49, which may be translating into increased use of e-health technologies. Several articles report studies conducted in different service contexts that evaluate telehealth models for treatment, service access or workforce development. Overall, these studies found telehealth to be a feasible and satisfactory delivery method from the perspective of both service providers and patients155-172. One of these studies explored the impact of teleoncology models of care in enabling safe delivery of chemotherapy in a remote area of north west Queensland (Mount Isa)171, finding no significant differences between the Mount Isa and Townsville Cancer Centre patients with regard to demographic characteristics, mean numbers of treatment cycles, dose intensities, proportions of side effects and hospital admissions. The study concludes that it appears safe to administer chemotherapy in rural towns under the supervision of medical oncologists from larger centres via teleoncology, provided that rural healthcare resources and governance arrangements are adequate. Several articles address the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of point-of-care testing for diagnosis and treatment management of a range of conditions173-175. Similar to those for the telehealth studies, these articles highlight the benefits of this technology in bringing treatment closer to home, especially for rurally based patients.

However, some important limitations to the overall effectiveness of digital and telehealth are identified in the literature. These include a need for adequate rural healthcare resources, including local health workforce65; infrastructure, including technical support163,165, training and governance arrangements159; as well as a need for e-health services to complement, rather than replace, community-led comprehensive health service models176. Staffing pressures were a barrier to telehealth use in one study163, and technical issues such as client position and camera angle were identified as a challenge in another165. One article contends that, despite its multiple benefits in providing timely and responsive services to remote clients, video-conferencing was unable to replicate the achievements of actual occupational therapists during community visits167.

Discussion

This review represents the first comprehensive sector-informed narrative synthesis of published literature on health system issues across northern Australia. A wide range of health sector actors including planning bodies, universities and training organisations, peak bodies and providers exist across the north, delivering primary, secondary and tertiary services and workforce education and training in highly diverse contexts of care. Although a great many exemplar health service and workforce models are apparent in the north, the synthesis presents a picture of a highly fragmented sector with many and disjointed stakeholders and funding sources. Overall, despite the many strengths of the northern health system, including expertise in training and supporting a fit-for-purpose health workforce, health systems in the north are struggling to meet the health needs of highly distributed populations with poorly targeted resources and ill-suited funding models. Ageing of the population and rising rates of chronic disease and mental health issues, underpinned by complex social, cultural and environmental determinants of health, continue to compound these challenges.

The literature overwhelmingly highlights the benefits of comprehensive primary health care, exemplified by ACCHSs, and the potential for significant cost savings to be made from investing in these models. There is convincing evidence of the health-promoting influence of primary health care, including its role in preventing illness and death and in creating more equitable distribution of health in populations177. Primary health care provides continuity of care that has been shown to reduce total hospitalisations, avoidable admissions and emergency department use in a range of settings in Australia and overseas178-180. In the northern Australian context, evidence shows that investing A$1 in primary health care in remote Aboriginal communities can lead to a saving of between A$3.95 and A$11.75 in public hospital expenses, in addition to the health and social benefits for patients181. Mental health, alongside cultural, social and emotional wellbeing, is a critical component of comprehensive primary health care. The overwhelming evidence of the benefits of such comprehensive, health-promoting (rather than disease-focused) models of care, and the gaps identified in this review, suggest important opportunities for strengthening comprehensive primary health care in the north.

The literature also highlights widespread recognition that community preferences, control and participation are essential in healthcare decision-making; but outside of ACCHSs, implementation of community engagement goals into practice is highly variable. A similar gap is identified between stated commitments of services and policymakers to address the social and cultural determinants of health, and policy action and funding. Addressing these gaps should be an urgent policy priority to improve the cultural responsiveness and overall effectiveness of health services in the north. Action in these areas is widely supported in the literature: improving access to and suitability of housing, nutrition and transportation can significantly improve health outcomes and influence healthcare patterns of use118,182. Furthermore, cultural competence of healthcare services and professionals is associated with increased likelihood that Aboriginal people will access services183,184. The findings of this review provide a strong rationale, based on both scientific evidence and widespread policy commitments, for increased efforts to prevent poor health by resourcing programs that target the social, cultural and environmental determinants of health and support co-produced policymaking. Policy-focused, and co-produced, evaluative research should be mobilised to help guide these efforts, with a particular emphasis needed in future research on understanding governance mechanisms that enable cross-sectoral and cross-cultural activity, and community leadership and engagement.

The ongoing health workforce shortages identified in this review highlight the urgency of investing in evaluation and reform of the jurisdiction-based educational pathways and governance structures that act as barriers to timely recruitment, and in adequate resourcing of training and staffing models that support local career pathways, strengthen retention and stabilise the primary care workforce in the north. High staff turnover impacts on health outcomes for people living in remote areas, with increased staff turnover associated with higher hospitalisation rates and higher average hospital costs185. Ensuring a sustainable remote health workforce while preventing excessive turnover requires investments in targeted recruitment; adequate support, including access to good quality housing and information and communication technologies; competitive and realistic remuneration packages and retention incentives; effective and sustainable workplace organisation; a collegiate professional environment; and access to family supports and broader community amenities131. Established evidence also supports continuing investment in rural generalist workforce models, which have been shown to improve workforce retention, improve health outcomes and reduce costs in rural areas186-188. The gaps in the literature pertaining to rural generalist training pathways outside of medicine highlight important opportunities for future research to further test and evaluate multidisciplinary models of rural health workforce development in northern Australia. Specific and urgent investment is also needed to develop Aboriginal, and Torres Strait Islander, health workforce career pathways, including leadership development189.

Strengths and limitations

This scoping review is the first attempt to comprehensively synthesise and describe the published literature on health system issues across northern Australia. Strengths of the study include its use of a health system (rather than solely health service) framework and its focus on both peer-reviewed and grey literature. This approach enabled examination of several inter-related structures and processes that combine to determine key health system strengths and weaknesses, and comparison of policy approaches and intent with research evidence. The use of several search strategies, including database and website searches as well as stakeholder recommendation, increased the likelihood that the findings are representative of the key service and workforce issues in the north.

A key limitation, which reflected the breadth of the review, was the narrow window of eligibility for peer-reviewed articles (notwithstanding the inclusion of seminal articles outside of the 2015–2019 date range), which likely resulted in the omission of research findings relevant to the review aim. Future syntheses might address this limitation by undertaking more of a deep dive into some of the specific issues and gaps identified in this broad review, such as those relating to community co-produced policymaking and research, data interoperability in and between northern Australian health services, and cross-sectoral and cross-jurisdictional governance arrangements for service and workforce planning.

Conclusion

Policy goals about developing northern Australia economically need to build from a foundation of a healthy and productive population. Improving health outcomes in the north requires political commitment, local leadership and targeted investment to improve health service delivery and workforce stability, building from the evidence to direct resources towards strengthening community-led comprehensive primary health care. This requires coordinated efforts across many organisations and the three jurisdictions, drawing from past collaboration experiences. Further evaluative research, linking structure to process and outcomes, and responding to changes in the healthcare landscape such as the rapid emergence of digital technologies, is needed across a range of policy areas to support these efforts.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the advice and feedback provided from a range of stakeholders from across the north, especially individuals involved in the jurisdictional advisory groups established for the broader Situational Analysis project. The authors also thank and acknowledge the Cooperative Research Centre for Developing Northern Australia for supporting the review.

References

You might also be interested in:

2011 - Farewell Ralph McLean - a quiet contributor to rural health