Context

We as Indigenous people live out our lives in two worlds according to our custom and tradition and the modern reality1.

Governance is the collective organisation of a group of people within a commmunity or society to make decisions about an issue important to the group2. Governance includes the processes, relationships, insitutions and structures that evolve as decisions within the group are made2. Effective governance in Indigenous medical education research aims to facilitate an approach whereby Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples work collaboratively in decision-making structures3. Such an approach aims to assist research outcomes that promote and prioritise Indigenous worldviews and values4. A clear goal of Indigenous medical education research is to implement medical curricula that are effective in building workforce capabilities that can meaningfully improve Indigenous health outcomes5. As a result, inclusive governance values and supports the nurturing of relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous stakeholders to create meaningful praxis in the medical education research process. Key points regarding governance in Indigenous medical education research are shown in Box 1.

Effective Indigenous governance is a fundamental component in the decolonisation of both medical education and medical research institutions and requires meaningful Indigenous representation and inclusion6,7. Decolonisation is concerned with the long-term process of divesting colonial power and working to redress colonial legacies that negatively influence the health and wellbeing of Indigenous peoples8. Decolonisation of medical education research structures is required to facilitate the better preparation of the future healthcare workforce as skilled clinicians, health advocates and respectful researchers with a critical consciousness of their own cultural positioning and power9.

Solid collaborative governance structures are important in the context of the ongoing struggle for social justice and recognition of the rights of Indigenous peoples in the Australian community. This struggle is apparent in the refusal to implement the recommendations of the Uluru Statement from the Heart10, and in the absence of a treaty between the Commonwealth and First Nations Peoples11. These circumstances highlight the importance for medical education and research structures to take meaningful action in being responsive to the rights of Indigenous peoples and become agents of social justice change within their organisations and local communities12.

This article provides a rationale behind the Healing Conversation research project’s current governance approach, noting that this may change over time, in an effort to contribute to the ongoing discourse regarding effective governance approaches in medical education structures in both urban and regional settings.

Inclusive governance is of significance to rural and remote communities that have diverse population demographics, varied experiences of accessible health care and different exposures to structures and conditions that faciliate good health and wellbeing13. The Healing Conversations research project addresses this by having research team members based in regional locations and performing data collection within regional South Australia and Western Australia, concurrent with urban locations. This works to ensure the experiences of Indigenous peoples in rural and remote locations are included and represented in Indigenous medical education research, reflecting the diversity of geographical locations in which Indigenous communities live, and the larger proportion of Indigenous peoples living in regional Australia when compared to non-Indigenous Australians14.

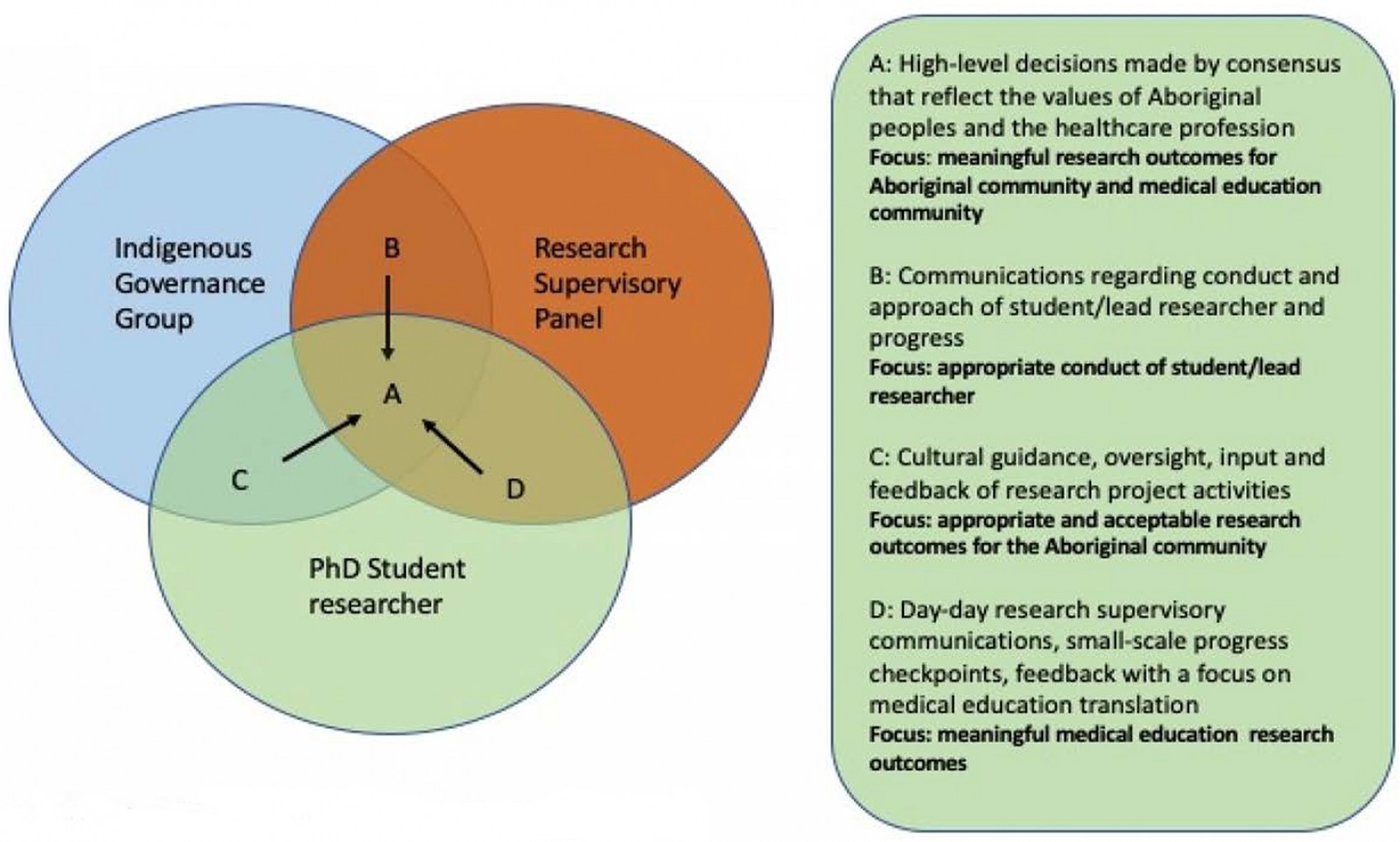

The Healing Conversations research team consists of three key entities that contribute to the overall implementation and accountability of the research process through an inclusive governance approach. These entities are the Indigenous Governance Group (IGG), Research Supervisory Panel and the PhD student as the lead researcher. The research team are located in urban and regional areas across South Australia, Western Australia and New South Wales.

Healing Conversations forms part of a PhD student research project by an Indigenous medical academic supervised by Indigenous and non-Indigenous medical practitioners with expertise and experience in Indigenous health and medical education. The IGG comprises four Indigenous health academics with diverse knowledges and expertise. One of the IGG members is also a member of the supervisory panel to ensure effective integration and communication of ideas, perspectives and concerns between the IGG and supervision entities. Effective collaboration and communication among the entities underpin efforts to guide meaningful action in this space15 and this is done by phone, online conferences and face-to-face meetings coordinated by the PhD student, who is based in a regional setting.

The roles and interactions of the Healing Conversations research team are outlined in Figure 1, noting the foundational role of the IGG in providing expert cultural knowledge, guidance and oversight to the implementation of the research project.

The described approach to inclusive governance is cognisant of the hierarchal and power-laden environment that accompanies medical education and research7. It is proposed this approach can assist authoritative structures conceptualise how they can be more responsive to Indigenous worldviews and knowledges, given the contemporary and historical context of colonisation in the heathcare system.

Box 1: Key points relating to governance in Indigenous medical education research.

Box 1: Key points relating to governance in Indigenous medical education research.

Figure 1: Actions and social coordination of the Healing Conversation’s research team resulting in consensus decision-making (A).

Figure 1: Actions and social coordination of the Healing Conversation’s research team resulting in consensus decision-making (A).

Issue

The torment of powerlessness

Indigenous peoples, in exercising their right to self-determination, have the right to autonomy or self-government in matters relating to their internal and local affairs, as well as ways and means for financing their autonomous functions16.

Disparities in healthcare outcomes for Indigenous peoples when compared to non-Indigenous populations are well known and researched in the international medical literature17,18. Reduced life expectancies, increased exposure to environmental and social risk factors for disease and reduced access to opportunities that facilitate good health, combined with reduced quality of healthcare provision, form the daily lived experienced for Indigenous communities living in Australia18-22. The complex ecosystem of health inequities illustrates why a multidimensional approach is needed to shift health disparities and promote healthy, strong communities for current and future generations of Indigenous peoples18,22,23. Indigenous medical education researchers are one part of this ecosystem. They can begin to challenge health inequities through sustained efforts to build responsive and capable health systems able to counter the effects of colonisation, racism and marginalisation on health outcomes24,25.

In order to achieve responsive and capable health systems, effective governance structures must embed Indigenous voices in medical education and research, prioritising a spirit of agency and ensuring structures are reflective of the contemporary needs of the Indigenous community26,27. This calls for a dynamic approach to governance to ensure medical education and research are effective and aligned to current trends and emerging evidence according to the voices and knowledges of Indigenous peoples7,26,28. Such emerging trends include the growing discourse around the integration of the cultural determinants of health into clinical care29 and the need for clinicians to be skilled and knowledgeable in addressing the impacts of colonisation and racism on Indigenous health outcomes20,30-32. Research methods and medical institutions that fail to address and counter the effects of colonisation, racism and dispossession are unable to make a meaningful contribution to improving Indigenous health7,24,32.

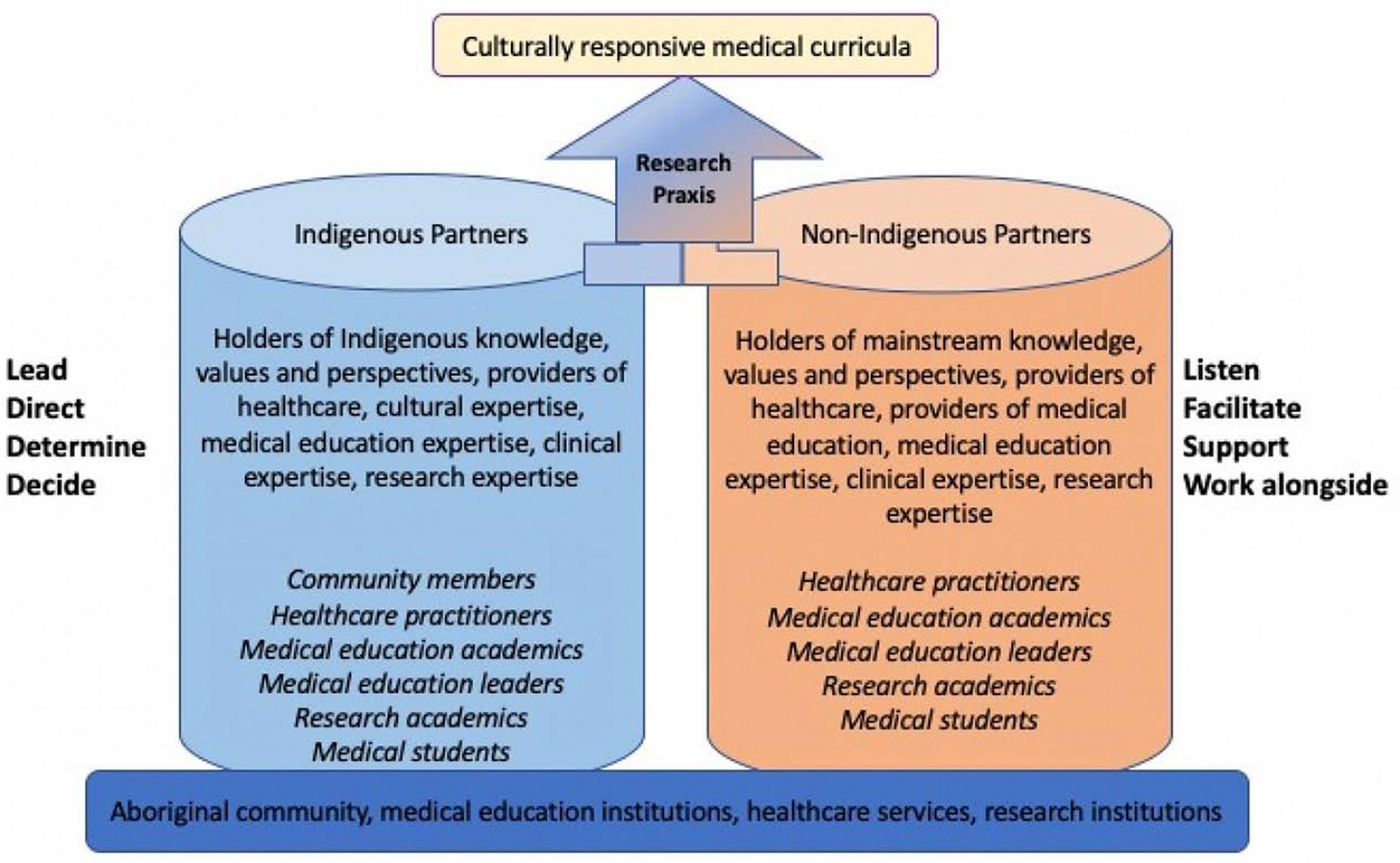

Healing Conversations is contributing to the evidence base. The project documents effective ways to build the skills and capabilities of healthcare practitioners, including the capability of practitioners to be responsive to experiences of racism and the role of cultural determinants within a clinical encounter33. The research has developed and is in the process of validating an alternative lens regarding capacity development of healthcare practitioners in Indigenous clinical communication skills in urban and regional settings. The inclusion of non-Indigenous partners is important to ensuring the translation of research outcomes to daily clinical practice, given the current diversity of the Australian healthcare workforce34 and the collective responsibility of this workforce to redress health inequities35,36. As knowledge translation is situated within mainstream academies, effective collaborative approaches are needed. Achieving this requires clear recognition of the roles of Indigenous and non-Indigenous partners in medical education research and practice, which can be achieved through a collaborative governance approach. This can work to ensure mainstream approaches are adapting to Aboriginal community contexts and needs, and not the other way around7.

Interconnectedness and governance in Indigenous medical education research

Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be. This is the interrelated structure of reality37.

The relevance of an inclusive governance approach is reflected by the dual worlds in which Indigenous peoples live in every single day3. Indigenous peoples in medical education research must balance maintaining their internal governance legitimacy with their external governance legitimacy demands3,38. Internal legitimacy is maintained through the support of peoples who share their cultural values38. External legitimacy requires Indigenous peoples’ contributions to be effective and credible to the medical academy and its wider stakeholders. Both legitimacies need to be balanced to enable useful change3. Achieving a workable balance in maintaining cultural integrity, maximising self-determination while also allowing for praxis within the medical academy can be facilitated through an effective governance approach3.

Figure 2 demonstrates the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous partners in creating culturally responsive medical curricula through medical education research. The qualities of effective non-Indigenous partners to listen, facilitate, support and work alongside Indigenous pedagogies and knowledge paradigms to be included in the medical education research can begin to shift institutions from within to be more responsive to the needs and priorities of Indigenous peoples12. This shift ideally will be inclusive of high-level structures guiding research implementation to the connections and partnerships formed during day-to-day research activities39. Nurturing relationships among partners can foster a vision for change that not only relies on external directives but is owned by the institutions themselves12.

Institutional ownership for change reinforces the notion that improving Indigenous health outcomes is a united responsibility36. Non-Indigenous partners have a role in Indigenous medical education research given their positioning in healthcare provision40, medical education delivery41 and in contributing to the culture of healthcare institutions36. Non-Indigenous partners are well placed to support Indigenous medical education research by realising the rights of Indigenous peoples to self-determination42. They can facilitate the inclusion of values and worldviews into research processes by respecting Indigenous ownership and control of research outcomes24,25,43. Engaging in activities of praxis guided by an inclusive governance structure provides a useful lens in which to approach knowledge translation efforts in research. It emphasises that activities need to be inclusive of Indigenous and non-Indigenous partners while preserving and promoting Indigenous worldviews and values when enacting change.

Non-Indigenous partners, also known as allies, are characterised by their humanistic qualities of understanding patterns of marginalisation and how oppression is maintained44. A demonstrated ability to work alongside Indigenous researchers in a way that does not perpetuate oppression or enact paternalism44 is quintessential in effective governance. This is a key component of the conceptual notion of two-eyed seeing, which values the strengths of different knowledge systems to create new and innovative solutions to complex problems45. Embracing effective governance could provide a structure to support and facilitate non-Indigenous partners to build capacity in being able to respectfully contribute to Indigenous health advancement. It also provides the opportunity to review and be accountable to the humanistic qualities that are expected when working in Indigenous medical education and research.

Figure 2: Partners in Indigenous medical education research and their roles in governance.

Figure 2: Partners in Indigenous medical education research and their roles in governance.

Legitimacy in two worlds

Defining parameters of effective governance can be a contested space46, particularly when governance involves the coming together of different knowledge paradigms and worldviews. Also, the right way to do things in research can be guided by cultural values43,46. When implementing change that draws on the knowledge and perspectives from two worlds, close negotiation and respect for differences is required4. A consensus must be reached on how decisions will be made, how accountability is enacted and how the legitimacy of different knowledge systems is handled – along with a clear outline of the resource availability to facilitate these processes46,47.

The notion that effective governance requires positions of power to be perceived as having been acquired legitimately48 can be a challenge in Indigenous medical education practice and research. There might be conflicting worldviews and notions of who holds the authority and knowledge to make decisions42. The legitimacy of Indigenous knowledge and its place within mainstream medical education and research need to be acknowledged and embraced for a collaborative governance approach to be effective38. To support this there needs to be a willingness to accept that individuals will have different criteria to meet when defining their capacity to contribute to the research based on their role, experiences and expected scope of contribution. This is enabled in the Healing Conversations research team through relationship building that recognises and values Indigenous approaches to knowing, doing and being49.

Decision-making regarding Indigenous governance, knowledge and capacity needs to be led by the Indigenous members of the research team to ensure respectful and appropriate decision-making is enacted, and to prevent further oppression and the maintenance of a colonial agenda27,47. This can be achieved through a number of approaches. In Healing Conversations, the IGG have a critical role in shaping the research outcomes in partnership with the wider research team50. The establishment of a dedicated Indigenous governance structure both empowers the Indigenous voice and facilitates accountability of the research process beyond the medical research institution. Indigenous representation is balanced with non-Indigenous representation, shifting away from a population parity approach. This works to facilitate effective consensus decision-making and prevents burden of advocacy being placed onto a lone Indigenous voice.

Lessons learnt

Implementing governance in Healing Conversations

To establish the IGG, the student researcher identified suitable individuals in Indigenous health research and education using information obtained through existing work relationships and networks. Suitability drew on factors including experience and known expertise in the field, geographical location, gender and availability to contribute to the project. The shared goal of increasing workforce capabilities to work effectively with the Indigenous community unites the research team. This is guided by shared values of respect for the role and knowledge each person brings, and an understanding of our own boundaries within the research process, negotiated through discussion and relationship building. Figure 1 demonstrates these boundaries, notably the space for the IGG and student researcher to have conversations and decision-making processes independent from the supervisory team when needed.

Defining community can be challenging in Indigenous health given the diversity within the collective Indigenous population51. The difficulty in being able to generalise what an entire nation of people thinks44 must be considered in governance approaches. The Healing Conversations research team address this by shifting away from a majority rule approach, to considering how to build consensus in the research outcomes52. Research outcomes from this process, given the tensions around defining community, further reinforce the importance of and need for Indigenous representation in governance structures to be maintained throughout knowledge translation efforts and into the structure of the medical academy. This will enable ongoing debate and discussion to ensure appropriate and meaningful inclusion and representation of Indigenous perspectives that is aligned to the local context15.

Research praxis is addressed in Healing Conversations through the development and maintenance of a research website, regular updates of participants and research stakeholders, presentation at international medical conferences, and community engagement in the research sites (South Australia, Western Australia). Additionally, early research findings are being integrated into medical education initiatives in clinical communication that are implemented using a collaborative approach with Indigenous and non-Indigenous medical academics. The overarching governance approach ensures that accountability of the research process is owned and shared by the entire research team.

Strengthening capacity and sustainability through governance actions

Capacity-strengthening is a fundamental process of effective governance38,46,47 and can be viewed through a collaborative lens. The capacity of Indigenous community members to contribute to change in positions from on-the-ground education activities to leadership opportunities within the medical academy can be strengthened through governance activities. Similarly, non-Indigenous contributors can strengthen individual and organisational capacities to support Indigenous leadership, include Indigenous knowledge structures and address organisational culture through their involvement and the nurturing of relationships within the governance process12.

The terminology regarding ‘strengthening capacity’ as opposed to ‘building capacity’ recognises the capacity to thrive, lead and govern that has existed within Indigenous communities for generations46. Strengthening the previously eroded capacity of Indigenous peoples to contribute meaningfully to improving health outcomes is what is now needed46 and is a fundamental reporting aspect of good research in this space24,47.

Capacities can involve technical skills, infrastructure, financial resources and equipment46, which all reflect the non-human structures that contribute to the governance community53. This can influence the sustainability of governance mechanisms at all levels54. The Healing Conversations research is strengthening the skills of the research team, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, in facilitating effective and evidence-based Indigenous clinical communication programs for medical students. Given the scope of the PhD project, no financial resources or equipment have been gained by the research team. However, this will become a key focus for negotiation when the project shifts to integrating research findings into medical curricula activities to ensure knowledge translation and praxis activities are appropriately resourced in the medical academy15.

Development of human-related capacities, although often not given high priority46, are fundamental to ongoing success in Indigenous medical education research and praxis. Such human capacities involve skills such as confidence, morale, values and motivation46. Without individuals who are skilled, confident and motivated to contribute to Indigenous medical education research, and subsequent medical education curricula activities, change cannot be sustained. Healing Conversations brings together motivated researchers in Indigenous medical education in both urban and regional settings. A shared vision for change is held regarding the capabilities of the future healthcare workforce to implement best practice and address the ongoing effects of colonisation in clinical encounters suited to the local context. The possible institutional benefits that can be gained from effective and inclusive governance structures support the consideration of this to be implemented widely in the medical education academy.

Effective governance in medical academies as a driver to institutional change

… stop talking, start listening, and work with us to deliver55.

Implementing the structure of governance as described in Healing Conversations offers a useful approach to conceptualising the roles of non-Indigenous and Indigenous stakeholders in Indigenous medical education research. It allows a structure that guides relationship-building and outlines the necessary human qualities and capacities to create and sustain meaningful change in Indigenous medical education research. It also requires collective responsibility and accountability for change in this space56.

It can be difficult to separate entities responsible for medical education research and medical education curriculum given the interwoven nature of the two. The next step in reflecting on governance in research is to consider how this approach transitions into medical curriculum implementation. In medical institutions, a multidimensional approach to enabling Indigenous agency is needed15. Indigenous representation is necessary in day-to-day curriculum activities, medical education leadership structures, the student cohort, organisational hierarchies and in ongoing external community engagement efforts15. This approach shifts away from having a single, standalone structure for Indigenous voices to be heard and included in medical education organisations to prioritising efforts to include Indigenous representation at all levels of the institution that are respectfully supported by non-Indigenous partners.

This poses a call to action to medical academies and their leadership structures to consider their commitment to addressing Indigenous health disparities by facilitating Indigenous self-determination at all levels of the institution54. This requires medical academies to:

- commit to a clear vision for action in Indigenous health

- work with Indigenous communities to embed collaborative governance approaches

- own their role in supporting, listening and facilitating Indigenous knowledges and perspectives into the academy

- outline their approach to capacity strengthening of all partners

- own their collective accountability to address Indigenous health inequities.

This will require firm commitment to the human and material resources needed to provide a sustainable and effective governance approach15, with a prioritisation to the development of the Indigenous medical education workforce.

Conclusion

Colonisation is a fundamental determinant of Indigenous health. Medical education institutions must acknowledge their historical and contemporary role in the colonial project and engage in an institutional decolonisation process35.

Meaningful inclusion of Indigenous peoples in governance plays a fundamental role in the development and maintenance of culturally safe individuals, organisations and institutions15. When done effectively, Indigenous representation in governance can serve as an expression of agency and self-determination within the community and can work to facilitate the multilevel capacity of institutions to respond to Indigenous health inequities12. The inclusion and prioritisation of Indigenous voices in the design and shaping of vital institutions such as medical education and health care can work towards enhancing the collective wellbeing of the Indigenous community38,39.

Medical education academies must now look to prioritise and embed Indigenous governance structures within curriculum and research activities and commit to capacity-strengthening initiatives that will sustain Indigenous representation over time in both urban and regional environments. This approach acknowledges the collective responsibility and accountability of healthcare systems to action and redress Indigenous health inequities in a way that fosters self-determination within the community and the medical academy.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge our esteemed colleague, mentor and friend, Professor Dennis McDermott, who died in April 2020. Dennis was a valued member of the research team, supervisor and IGG member.

References

You might also be interested in:

2021 - Why do some medical graduates lose their intention to practise rurally?

2015 - Employment experiences of immigrant workers in aged care in regional South Australia