Introduction

Outbreaks of waterborne pathogens constitute a public health concern, as large numbers of people can be infected within a short time1. Very frequently, their identification may be delayed as infected people may choose self-treatment with over-the-counter (OTC) anti-diarrheal drugs instead of seeking care from a health professional2,3.

In 2020, the identification and proper investigation of outbreaks was affected by the unprecedented health crisis of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The medical and public health services were overburdened and focused almost exclusively on the management of COVID-19 cases. Additionally, the fear of contracting COVID-19 discouraged people from visiting healthcare facilities4.

In this article we present the results of the investigation of a waterborne outbreak of Escherichia coli in Greece during the COVID-19 pandemic, in collaboration with a local pharmacy. Our aim is to emphasize the utility of alternative resources and channels of communication with the local population during outbreaks, which could also be used in remote areas of the country.

Initial notification and outbreak confirmation

On 15 June 2020 two cases of E. coli O157 infection were notified in a small town (3272 inhabitants) in the Peloponnese region of Greece. They were two women aged 40 and 59 years. Stool samples had been tested with the multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (FilmArray; Biomerieux, https://www.biomerieux.com.au/product/filmarray-multiplex-pcr-system)5. The two patients reported that other people in the same town had been sick with gastroenteritis. Nevertheless, there was no increase in the number of gastroenteritis cases based on hospital records.

We contacted the local pharmacist, who verified that there was an increased purchase of OTC anti-diarrheal drugs for several days in the town.

Methods

Epidemiological investigation

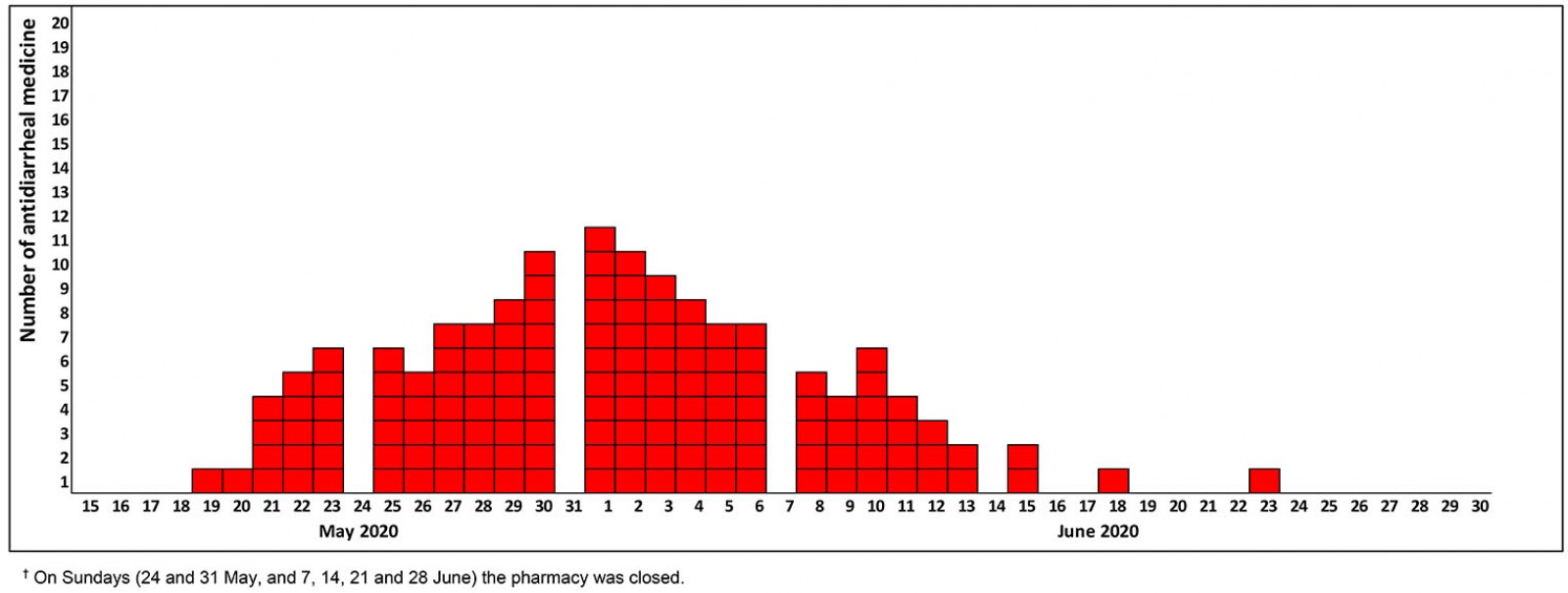

To follow up the course of the outbreak, we asked the pharmacist to provide us with the daily number of OTC anti-diarrheal drugs sold from 20 May 2020 onwards. The main hypothesis was that the source of the outbreak was the water supply. To test the hypothesis, a 1 : 1 case-control study was designed. A case was defined as any resident of the town who developed diarrhea between 29 May and 6 June 2020 and purchased OTC anti-diarrheal drugs from the pharmacy. A control was defined as any resident of the town who did not develop diarrhea during the same time period and purchased products other than anti-diarrheal drugs from the pharmacy.

To recruit cases and controls, we asked for the support of the local pharmacist. We requested him to provide us a list of his clients. We provided the pharmacist with a written request to participate in the study, to pass on to his clients, along with an informed consent form. The clients that agreed to participate were noted, and at the end of each day a list with the telephone numbers of the clients that consented was sent to us.

Interviews were conducted by epidemiologists of the National Public Health Organization at the central level by telephone; personal data were not recorded.

A structured questionnaire was used to record demographic characteristics, date of symptoms onset, clinical manifestations, participation in social events, and food and water consumption (tap and bottled water). E. coli O157 was the only pathogen identified at that time, so questions concerned a 5-day period prior to the onset of symptoms. Controls were asked about possible exposures on 26–30 May, because most people reported 31 May 2020 as the day of symptoms onset.

Laboratory testing of clinical samples

After our request, the pharmacist advised symptomatic clients to submit stool samples at the local hospital, if this was possible. He informed them that stool samples would be received without jeopardizing their safety in accordance with the COVID-19 infection control protocols.

Samples were tested with multiplex PCR for 22 pathogens with the BioFire FilmArray Gastrointestinal Panel5.

Environmental investigation and water sampling

We contacted the local municipality, which is the competent authority for the safety of drinking water and requested information on the town’s water supply system and probable failures at the distribution in May and June, and chlorination records. The municipality collected water samples that were tested for indicators such as total coliform colonies per 100 mL, required by the legislation6; as well as molecularly for norovirus and rotavirus.

Statistical analysis

Stata v12 (StataCorp; http://www.stata.com) was used for data analysis. We calculated οdds ratios (ORs) and respective 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). Associations statistically significant (p<0.05) in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariable model. The multivariable analysis was performed by multiple logistic regression using backwards elimination.

Ethics approval

The National Public Health Organization is authorized by Greek law to process personal data during outbreaks for epidemiological investigation. We requested informed consent from study participants. For children aged less than 18 years the consent was requested from their parent or guardian. Data were managed in accordance with the national and European Union regulations.

Results

The daily numbers of antidiarrheal drugs sold by the pharmacy are depicted in Figure 1. There was an increased number of sales from 27 May 27 to 6 June. Overall, 58 cases and 57 controls were recruited for the case-control study. The age distribution significantly differed between cases and controls (p=0.005) (mean age 53.6 v 43.4 years, respectively). Sex distribution was similar (56.9% and 56.1%, respectively, were females). Reported symptoms were diarrhea (100%), abdominal pain (10.3%), fever (>38°C) (6.9%), loss of appetite (5.2%), vomiting (3.4%), nausea (1.7%) and fatigue (1.7%). One case reported bloody diarrhea.

In univariate analysis, the development of gastroenteritis was significantly associated with the consumption of ice cubes made from tap water (OR= 34.8, 95%CI=10.0–147.6, p<0.001), and with teeth brushing using tap water (OR=7.9, 95%CI=0.9–365.7, p<0.001) and tap water consumption (OR=6.6, 95%CI=2.6–17.5, p<0.001). Consumption of bottled water had a protective effect (OR=0.17, 95%CI=0.06–0.43, p<0.001). In the multivariable analysis, consumption of tap water (OR=10.9, 95%CI=3.1–38.0, p<0.001) and ice cubes (OR=39.3, 95%CI=10.3–150.9, p<0.001) were independently associated with the onset of gastroenteritis.

Figure 1: Number of over-the-counter anti-diarrheal medicines purchased at the local pharmacy by date of purchase, 20 May to 6 June 2020.†

Figure 1: Number of over-the-counter anti-diarrheal medicines purchased at the local pharmacy by date of purchase, 20 May to 6 June 2020.†

Laboratory testing of clinical samples

Stool samples from 11 cases were collected. One was positive for shigatoxin-producing E. coli, one for enteropathogenic E. coli, four for E. coli O157, and one for Salmonella spp. Four samples tested negative.

Environmental investigation

The town is supplied with water from two wells. The drilling water is collected in a tank, where it is chlorinated and is distributed through the town network. No failures of the system were identified. The five water samples collected on 18 June tested negative. According to the available measurements on 5 and 14 June 2020, the residual chlorine ranged from 0.12 mg/L to 0.14 mg/L.

Discussion

Our investigation indicated that a waterborne outbreak occurred from 29 May to 6 June 2020 in a town in the Peloponnese Region of Greece. More than one pathogen was detected in stool samples. This finding along with the low values of residual chlorine supported the hypothesis of fecal contamination of the water supply network7. Mixed etiology of waterborne outbreaks is frequently reported8,9.

The focus of the local healthcare services at the time of the outbreak was on the management of cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection10. It has been documented that community pharmacists have played a key role during the COVID-19 pandemic, in informing the public, maintaining the supply of personal hygiene products, and making appropriate referrals as required. In parallel, pharmacists contributed to the provision of primary healthcare services, in the context of the gap on healthcare services that emerged due to the pandemic11.

Without the cooperation of the local pharmacist the confirmation of this outbreak would not have been be possible. The contribution of community pharmacists in early detection of outbreaks has become increasingly significant over the years, especially in remote areas10,12 and in areas that OTC medicines are easily accessible13. The implementation of a recording system of the number of anti-diarrheal and antiemetic drugs sold could function as an early warning system for foodborne and waterborne outbreaks13. In this outbreak, the daily number of OTC anti-diarrheal drugs sold was a proxy of the temporal distribution of cases, providing us with a rough estimation of the outbreak duration. Apart from the verification of the outbreak, the pharmacist also contributed to the investigation, as the onsite visit of an outbreak investigation team was not possible.

The main limitation of the remote coordination of the outbreak investigation is that we cannot be sure about the representativeness of the recruited cases and controls, even though specific guidance was given so that the selected sample would be as random as possible. Another limitation was the delayed identification of the outbreak, which probably did not allow the verification of its waterborne origin.

Collection of samples took place 22 days after the date of symptom onset of the first cases. The early detection of waterborne outbreaks is a prerequisite for minimizing their consequences14-16. Despite these difficulties, the results of the analytical study and the records of residual chlorine supported the waterborne origin of the outbreak, and local authorities were advised to strengthen monitoring of the quality of drinking water in the area.

Conclusion

This study of the outbreak showed that alternative methods for the detection and investigation of outbreaks can be used, in the context of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. This was the first time that local pharmacies were actively involved in a waterborne outbreak investigation in Greece. Utilization of already available resources is not only important during the challenging times of the pandemic but can also be used in the future for a more effective response to public health events, especially in remote areas of the country.

References

You might also be interested in:

2022 - Home visits in rural general practice: what does the future hold?

2015 - Effect of rural practice observation on the anxiety of medical students