Introduction

Oral health is valued by Australian Aboriginal people, but structural factors, including organisational factors and cost of care, are seen as barriers to accessing care1,2. Receipt of appropriate and timely dental care by Aboriginal people in remote communities is challenged on several levels. Navigating the often complex and confusing bureaucratic processes and system factors can be difficult in the absence of any support or advocacy, and the lack of culturally appropriate service delivery can discourage care seeking3. Also, geographical remoteness, a lack of available services within the community and capacity to travel long distances, and the impact of travel on the family, further compound the challenges of accessing care.

Aboriginal children in Australia and Western Australia (WA) have higher rates of dental decay than non-Aboriginal children4,5. In WA, a large proportion of the decay experienced by Aboriginal children is untreated decay (1.6 times greater than that among non-Aboriginal children); the inequity, however, is greater among children in the north-west of WA, where untreated decay among Aboriginal children is six times greater than that among non-Aboriginal children6.

Reports of patient experiences are useful adjuncts in evaluating strategies used in service delivery and are increasingly seen as an important component of evaluating health services because they contribute not only to ‘measuring system performance, but also provides insights into patient journeys and their quality of care’7.

Evaluation of an interventional research project, based on a minimally invasive model of care to overcome some of the perceived barriers, found the model to be effective in delivering primary dental treatment to young children in remote Aboriginal communities8. This article reports on the experiences of parents and carers and perceptions of the use of the minimally invasive dental treatments delivered to young Aboriginal children in remote communities in the north-west of WA. The objective was to elicit views of parents and carers to enable the evaluation of a model of care for dental treatment in young Aboriginal children with a view to its implementation in WA and, potentially, other remote communities.

Methods

Full details of the core randomised controlled trial have been reported elsewhere8,9. Briefly, the study was a parallel two-arm, stepped-wedged, cluster-randomised controlled study set in the Kimberley region of WA. The aim of the study was to develop, implement and evaluate a model of primary dental care based on minimally invasive approaches, including the atraumatic restorative treatment10 and the Hall technique11 (ART–HT) (no dental drill or local anaesthesia) to provide dental treatment to Aboriginal preschool children aged 0–6 years.

Participating communities (n=25) were randomly allocated into early (12 test communities, n=177) or delayed intervention (13 control communities, n=161). Participants in the early treatment group were offered dental treatment using the ART–HT approach after their baseline examination, and parents in the delayed intervention group were advised to follow up their child’s dental treatment through their usual dental service provider (which includes government dental services, volunteer non-government dental services, private practitioners and the Royal Flying Doctor dental services). Children in both groups were examined again at follow-up 12 months later and were offered care using the ART–HT approach.

Participants

Parents and carers who attended with a child study participant for clinical care at follow-up were invited to take part in either focus group or one-to-one interviews. All interview participants were provided with a $50 voucher redeemable at the local community store for groceries and power cards as compensation for their time.

Data collection

All interviews were conducted, using an interview guide, by two of the researchers: the Aboriginal Research Officer (ARO, Aboriginal, female) and the chief investigator (non-Aboriginal, male). Interviews were held in convenient locations for the interview participants depending on venue availability, such as a classroom or an office, on a veranda or under a shady tree. Privacy and confidentiality were maintained throughout the interviews. Interviews were audio-recorded with permission, and at the end of the interview the ARO canvassed the interview participants on their level of satisfaction with regard to cultural safety and transparency during the interview. The recordings were transcribed verbatim by an independent transcribing agency. The communities located in the Kimberley region of WA represent more than 30 language groups, with English being a second or third language for some of the interview participants. The ARO further translated the audio-recordings where responses had been delivered in Kriol (a creole language spoken by Aboriginal people across northern Australia) and in cases where the agency transcriber was not familiar with the diversity of the language groups. A copy of the transcript was provided to all adult participants, by post, by email and in person, wherever possible, to allow them the opportunity to confirm its accuracy and make any additions or changes. No adjustments were made.

Interview guide

The guide was semistructured and the open-ended questions were based on those used in a previous study that evaluated parental perceptions on the use of a minimally invasive treatment approach to dental treatment among children scheduled for a dental general anaesthesia12. All interview participants were asked the same questions, guided by the yarning approach13.

The interview guide questions were:

- What were some of the good things that you have experienced with your child’s dental care?

- What were some of the ‘bad or not so good’ things you have experienced with your child receiving dental care?

- What sorts of things could have made your child treatment better?

- How did you feel about the place where you received treatment? How could it have been better?

- How did you feel about the way the treatment was carried out and how could this be better for your child?

- Do you think this research has helped you understand more about your mouth health? If so, what do you know now that you didn’t know before?

Data analysis

Transcripts were read independently by three authors (SP, SC and PA), and preliminary coding was undertaken following the approach of Braun and Clarke14. The analysis was not rooted in a particular discourse analytic framework nor driven by theory, but rather had a more utilitarian aim of understanding parent and carer perceptions and experiences of care. The thematic analysis framework was seen to be appropriate for distilling the realist/lived experiences of the study participants and to provide a rich and detailed account of the data15.

Initial thematic development was undertaken with the readers making annotations on the transcripts and then developing a flowchart that identified commonalities and differences between the participants from the two groups. The coding was undertaken within the framework of the interview guide. The analysts met several times and identified the emergent themes. Where differences were encountered, the matter was resolved through discussion and mutual agreement. The transcribed texts were imported into NVivo v12.6.1 (QSR International; http://www.qsrinternational.com), and coding and identification of emergent themes were further refined. The process was iterative, and codes were added, eliminated or consolidated into other codes to assist in developing the emerging themes.

De-identified transcripts were further reviewed by an author not involved with data collection but familiar with thematic analyses (HF) and the other authors (two Aboriginal researchers and one non-Aboriginal researcher). The analysts subsequently met on several occasions (by teleconference) to review the findings and agree on the final themes and subthemes. Relevant, illustrative comments from interview participants that conveyed and reflected their responses to the research question were then extracted from the transcripts.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for the study was granted by the WA Country Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee (WACHS HREC project reference 2017/01), the WA Aboriginal Health Ethics Committee (project reference 790) and the University of Adelaide Health Research Ethics Committee (H-2017-015). Participants provided signed informed consent. The trial was registered with the ANZ Clinical Trials registry (ACTRN12616001537448).

Results

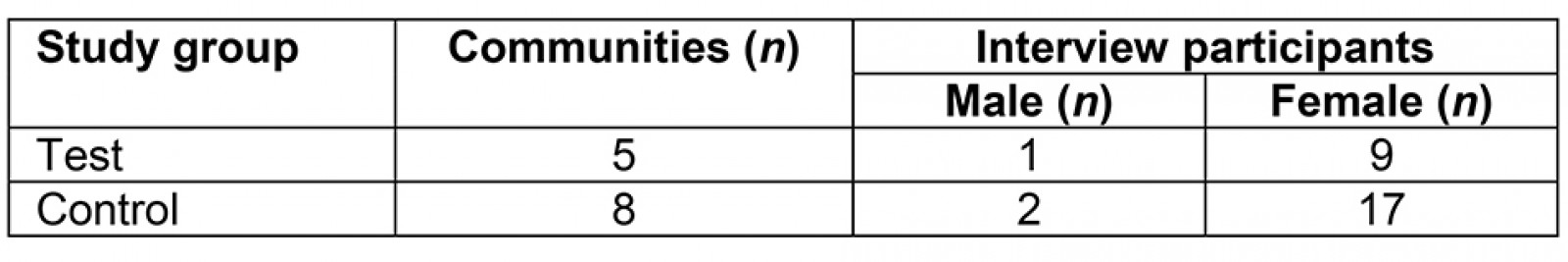

Twenty-nine parents and carers participated in one-to-one interviews (none opted for focus group interviews) (Table 1). Interview participants consisted of 3 males (3 fathers) and 26 females (22 mothers, 3 grandmothers and 1 great aunt). Interview duration ranged from 3 to 30 minutes.

The three principal themes and the subthemes that emerged after thematic analysis were:

-

access to care

- access barriers and service availability

- impact on the child and family due to lack of access to care

-

experience of care

- cultural safety

- child-centred care

- comprehensiveness of care

-

community engagement

- service information

- engagement

- oral health education.

Table 1: Characteristics of test and control study groups

Access to care

Covering an area of more than 400 000 km2, the Kimberley region of WA is classified as remote or very remote; with a low population density, availability of dental services is limited.

When it comes to our kids’ teeth and dental care in our community we pretty much don’t have much … So it’s non-existent, we don’t have these sort of services in [community’s name]. (ID592, female control)

Interview participants reported infrequent visits and the limited time spent by service providers in community.

It’s the first time they’ve been here in two years, because they need to do it more regular … It doesn’t matter what they’re doing now, it doesn’t work because every two years is a long time. (ID819, female control)

Participants also reported that having limited access to a vehicle, financial demands, unfamiliarity with larger towns and the time away from school and work placed additional stress and burden on families.

Um the closest one is [town’s name] … maybe 4 or 500 kms. (ID588, female test)

Like I say, we live 100 kms from our dentist, which is in [town’s name] and sometimes it’s just a struggle to get the kids in there, especially with parents who don’t have cars, the distance you’re going to travel … It is a challenge. (ID664, male control)

It’s very hard getting into town from here … Into town and to organise a car, lift, or get the hospital to pick us up. It takes hours … It costs money … when we have to go into town, we have to pay for it. (ID819, female control)

Unclear and confusing bureaucratic processes encompassing eligibility criteria, forms, waitlist appointments and fees were additional challenges.

Yes. I had to take [child’s name] to the [town’s name] dentist. It’s been a long time waiting on the list because she really had sore teeth. We got referred to the [town’s name] dentist but couldn’t do it because we had to pay money for it and then they told me to go to Centrelink and Medicare [Australian Government payments and services program] and all that because we are in the community. It’s hard to know what to bring, all this stuff, so I didn’t go with that. (ID663, female control)

A lack of dental services available for young children in remote communities was highlighted and participants were confused about the age at which the children were eligible to receive care from visiting oral service providers.

No, not in [child’s name] age group. It’s usually from Year [grade] 1, I think and primary … they won’t see, like, four year olds. (ID596, female test)

She’s not school age, they only come to see school age kids … that’s on the list anyways, like they just told me it’s school kids, bringing school kids. (ID591, female control)

Impacts resulting from the unavailability of services for preschool children were also reported.

… just go to the clinic and just, I asked them what can I do for [child’s name], because having them problems with his teeth, he was suffering. So they told me to take him into [town’s name] and then because he was a bit too small, they said he’s not old enough to go into the dental … Just to help them to stop them from suffering. (ID593, female control)

Participants appreciated services that were targeted towards younger children and where comprehensive care was provided in community.

If it hadn’t been for this program [ART–HT] I wouldn’t have taken her for any treatment unless she’d been in obvious pain … So it was great to catch decay that was starting, not causing problems yet. (ID666, female test)

So yeah, … having the kids been treated out in the community. So if we had to have any work like that, we’d have to go to [town’s name], fillings and that. So you’ve brought the team to do it here, that’s really helpful you know. (ID592, female control, reflecting on test treatment approach provided at follow-up)

Disappointment was evident when only examinations were performed, leaving parents and carers with unmet expectations of treatment for their children.

Um but they just check it and they’ll say what they gotta do you know to their mouths what needs to be done, um but then you gotta go into town you know. (ID860, female control)

… there’s no follow-up treatment unless I travel into town and take the child back to see a dentist … They check the teeth and then we go to [town’s name]. (ID592, female control)

Accessing care outside of the community challenged the cultural safety of participants, who reported on the difficulties in navigating unfamiliar environments and processes.

Instead they’re putting a baby’s appointment in different town and it is struggling, because some of us we don’t know where to go in a big town … We’re from a local community here in [community’s name] and for me I went to [town’s name] and I got lost … we still don’t know any other place but [community’s name]. We’re brought up here and we want to be here, home for our children and for ourselves, because we don’t want to go [town’s name] … (ID593, female control)

However, they also acknowledged the appropriateness of the delivery of care with the tested model.

One of the good things was that it happened to be at a child centre … seeing other kids around, so it just moved the focus a bit … So I think being at a kids’ centre or a kids’ playgroup, the kids feel more safe … So where the service is provided is really important. (ID863, female test)

But like this … Project, to actually come into the community which saves us a lot of hassle, save the parents without cars a lot of hassle and the kids actually get to see the dentist. (ID664, male control, reflecting on test treatment approach provided at follow-up)

Experience of care

A feeling of ease and comfort, which builds a trusting relationship between the provider team and the care recipient, was reported.

I think it has to come from the staff, I reckon for the kids to feel that they can trust them. (ID863, female test)

He was more happy. And I think because he had a good friendly staff to deal with, and he was relaxed, so the environment was a good environment, and he felt well looked after I’d say. (ID589, female control, reflecting on test treatment provided at follow-up)

Child-centred care positions the child at the centre of the care and empowers them to engage in the care process. Interview participants reflected on the holistic and child- and family-centred approach employed by the project clinical team during the oral care for their children.

It’s alright like really calm and thing and not rushing it’s just right nice and step by step it’s alright I reckon … she’s saying it there, the things I wanna say so it’s alright. (ID672, female test)

She very quickly trusted all the staff here. She was giggling. And that’s everybody, both in the first check-up and then with the treatment. Just the way she was treated. She was relaxed and I didn’t need to be there. Usually she’s really clingy. (ID666, female test)

I think, yeah just the way they treated, talked to her, made her feel comfortable, you know, let her know that she didn’t have to go through with it if she didn’t feel comfortable … And my daughter is happy, so. (ID862, female test)

The minimally invasive approach was well received by parents and children, and the benefits of this treatment approach were compared with that of standard dental care approaches.

She’s just had all the fillings done and one was really deep and it could have caused her pain. I don’t know how I would have got her to a regular dentist. Especially if there were needles and drills involved. (ID666, female test)

Um yeah it was good I liked it, yous did everything. Yeah not so much needle and things that makes them scared so yeah it was good he liked it yeah. (ID596, female test)

Parents and carers reported on children having improved self-esteem and a sense of achievement following episodes of care, with many expressing their children’s confidence and eagerness to return for further treatment.

Very satisfied with his treatment and the things that he got done with his teeth. He’s very proud that he’s been to the dentist … He was awake early this morning ready and waiting to come to get his teeth done. (ID596, female test)

So it must be he likes it now because the one from yesterday, then doing good. That’s why he wanted to come back earlier than the last time, if you guys can do it early. It’s good I reckon. (ID672, female test)

Now, I see [child’s name] is more confident coming to the dentist. Last year, he was freaking out, ‘I don’t want to go to the dentist’ and all of that, but now he feels more confident coming. (ID671, female control)

Community engagement

Parents and carers spoke of the value of strong engagement with the community and of receiving clear and timely notification of service provider visits by the project team.

… where as you [project team] go out and then you tell people and then there’s the signs up and everything, so, yeah, that was good. (ID596, female test)

I know that you guys [project team] … bring flyers out, so that was like two weeks beforehand or a week, so they came around to my house and gave me these that you mob were coming. Then I had another person knocking on my door to say that you mob were here last week … One of the Councils told me that you mob was here. I said that’s good. (ID663, female control)

In contrast, when there was limited community engagement, parents and carers were poorly informed and subsequently missed the opportunity to access care.

Yeah, they [other services] didn’t promote themselves … In school newsletters or office or the shop or just going around letting people know that the dentist is here. Knocking on people’s door. (ID663, female control)

Yeah no dentist around here keep missing them … Nah … Maybe they [other services] give us a heads up when they coming maybe a week early or something … Put a poster in the shops. (ID590, male control)

… and there’s no notices and the clinics, they put out notices but we don’t see any around … (ID596, female test, referring to other services)

Interview participants also reflected on how information about treatment needs and regimes, given in lay terms that were easily understood, reinforced the feeling of trust and collaboration between the service provider and the child and parent or carer.

So the treatment that he did get was like quick, and made it clear what was happening, what was going on, so well informed … like easy to understand and clear. (ID589, female control, reflecting on test treatment provided at follow-up)

Yep, yeah, I understood everything, like, how they explained it and not like in hospital terms or doctor terms, it was all straightforward, so I understood everything that was done for [child’s name] and his teeth. (ID596, female test)

They reported times when receiving treatment provided by other services resulted in a reluctance to attend for follow-up care because they had felt shamed or were made to feel guilty about their children’s teeth.

… the kid would go in there and it’s just straight to the point, and we’re doing this and we’re doing that, the kids just wants to get out of there … I think a few years ago now when I took one of my boys, he was pretty young. And that happened so he just didn’t want to go. (ID863,female test, reflecting on other services)

And like when I went to the dentist with my first child I got a bit of negative comment from the dentist, and it was discouraging for a first time mum … I didn’t want to go back. (ID591, female control)

The provision of non-judgemental and attainable information on maintaining good oral health for their children was valued.

Okay well with your team coming to see us in [community’s name] it’s been good because I’ve been able to find out how my kids’ teeth are and that, and getting them checked and that. And also understanding how to care for them and all that … so it’s been good you mob coming to see us out in the bush. (ID592, female control, reflecting on test treatment approach provided at follow-up)

Just also different things … caring for it and I haven’t been slapped over the fingers for providing her with so many sweet things. People made suggestions as to how I could help cut down how many sweet things she has and how to eliminate chance of more decay. (ID666, female test)

Discussion

Parents and carers interviewed in this project expressed a range of views that were distilled into three principal themes of access to care, receipt of care and appropriate community engagement.

Aboriginal Australians do not always have the same level of access to health services as non-Aboriginal Australians, which may be due to remoteness, affordability or a lack of cultural safety. The challenges confronted by Aboriginal people, especially those in remote communities, in accessing oral health services have been reported2,16,17. Parents and carers interviewed in this study reported challenges in accessing oral services in community, and of the burden and impact of having to travel long distances to seek care. The capacity for families to travel hundreds of kilometres to a regional centre is challenged by access to a reliable vehicle, capacity to pay for fuel on top of paying for other essentials and the impact on the family by the need to travel long distances. Structural and system factors, including bureaucratic processes and the loss of cultural security, further compound the barriers. In spite of this, the parents and carers also demonstrated resilience and strength in overcoming the barriers in trying to obtain care for their children; for example, one reported leaving the community very early in the morning to travel a few hundred kilometres in order to be able to attend a clinic in a central location after being told that their child was too young to have dental care in community by the visiting service provider team. Improving access to care is expected to reduce the inequities in oral health between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people18.

The tested model adopted a holistic, child- and family-centred care, which sees children as being more than their illness with a ‘concern and compassion for their overall experience and acknowledgement of children … and their parents as partners in care’19. Care was also delivered within community in a culturally respectful, shared-care manner that was perceived by the parents and carers to be better for their children and themselves. The use of minimal high-tech equipment enabled services to be delivered in non-traditional settings such as community centres and childcare centres, which parents and carers viewed as culturally safe environments in community, instead of having to leave the community for care. Cultural safety was further enhanced by the presence of the ARO, who provided much-needed cultural brokerage and ensured a willingness to return for care and follow-up of treatment advice.

The model of care also facilitated development of a trusting relationship because it was delivered in a ‘non-discriminatory, non-judgmental and respectful’ manner, which is critical for reducing the disparities in health between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people1. Nurturing positive relationships encourages trust in people and in the processes or prescribed treatment20. Establishing a caring environment in which the child was put at ease and made comfortable was identified by the study participants as a critical component of care. Parents and carers were at ease when their child was at ease. The absence of care and empathy being a deterrent to care seeking by Aboriginal people has been highlighted3, whereas a trusting relationship between the clinical team and the recipient of care as a critical component of care delivery has been reported21.

Patient engagement is viewed as an integral part of health care and a critical component of safe, person-centred services22. Lack of appropriate engagement and poor information sharing to facilitate access to care as well as information enabling maintenance of oral health for self and their young preschool children was also reported in interviews with parents and carers. Similar findings have been reported elsewhere1,17. Some participants in this study held misconceptions about their child’s eligibility to access care from visiting dental teams. Other participants reported that visiting teams did not provide enough information about their visit to communities, the child’s dental treatment, or ways of looking after the child’s teeth to avoid problems. Parents and carers were able to contrast their experience of the standard model of care with the tested model of service delivery in which extensive community engagement and information sharing was undertaken.

Acceptability of the atraumatic treatment (no dental drill or local anaesthesia) was high among the child participants and interviewed parents and carers. Satisfaction was expressed when children received comprehensive care in community, and parents and carers reported adverse impacts when care was ad hoc; for example, when only examinations were performed and parents and carers were advised to seek the required treatments at a larger regional town – often hundreds of kilometres away. The challenges for families to follow through with referrals are often a matter of prioritising among other competing demands, and, sometimes, dental treatment needs are foregone with the resultant impact of pain and functional impairment, sleep interruptions and interference with social function16.

Limitations in this study include the fact that the participants were volunteers within a cluster-randomised trial and thus may not necessarily be representative of all participants in the randomised controlled trial or of their community. However, participants were from communities across the Kimberley region and thus the views probably reflect the views held by parents and carers in those communities. Some interviews were undertaken by a non-Aboriginal male, which may have limited the amount of information shared by Aboriginal female participants. However, checking the fidelity of the responses of the participants with the Aboriginal interviewer suggested this not to be the case. The interviews were undertaken in non-standard settings, depending on the availability of facilities, but the variation in the settings was across both groups, thus should not bias the response by the participants.

Conclusion

The findings from this study suggest higher parent and carer satisfaction with care that was accessible and delivered in a child- and family-centred manner, and where service providers had appropriately engaged with the community and families. The minimally invasive dental treatment approaches were well accepted by the children and their parents and carers. This, coupled with the findings that the use of minimally invasive treatment approaches, without the use of the dental drill or local anaesthesia, could deliver effective care in remote communities8, suggests that such a model of care should be considered in delivering oral healthcare services for young children in rural and remote locations.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the traditional custodians of the land upon which the research was conducted and thank the parents for their willing participation in interviews and the participating communities and the Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations. The research was supported by funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council (APP1121982), Colgate Oral Care Australia and Dental Health Services, Health Department of WA.

References

You might also be interested in:

2017 - Developing a medical workforce for an Australian regional, island state

2015 - Rural health activism over two decades: the Wonca Working Party on Rural Practice 1992-2012