Introduction

Pain is a common and distressing symptom of cancer and its treatment, affecting more than half of people with cancer (‘patients’) across the disease trajectory1. Qualitative research with patients and families is informative in elucidating barriers and facilitators to cancer pain management and understanding their priorities. Two meta-syntheses of qualitative research have highlighted a need to improve the patient-centredness of pain management by better individualising care to each patient’s needs and taking a partnership approach that upskills the patient and family to self-manage2,3.

A notable gap in the qualitative research from developed countries concerns the experiences of patients receiving care for cancer pain outside urban settings. Only one study has focused on issues faced by rural patients with cancer pain. That Canadian study included patients with advanced cancer who had to travel an average of 177 km to receive specialist palliative care4. Patients faced interruption to their lives and challenges to pain control during their commute. However, they still felt that their rural location's lifestyle and community support outweighed the increased access to the care they would have gained from moving to an urban area.

To date, no study has explored the experiences of Australian patients or families regarding the management of cancer pain in a non-urban setting. Australia is a large country (7.7 million km2) with a small population (25.9 million)5. Major cities constitute less than 1% of land mass, yet are home to nearly three-quarters (72%) of Australia’s people, with the remaining population unevenly distributed across areas that the Australian Standard Geographical Classification remoteness structure terms as inner regional (ie urban) (17%), outer regional (9%) and remote/very remote (2%)6. Historically, survival for people with cancer has been worse for Australians living in outer regional and remote areas than urban areas due to more limited access to services for diagnosis and treatment7. However, since 2010, the Australian Government has invested heavily in capital grants supporting outer regional cancer centres (henceforth shortened to ‘regional’). This investment means that most outer regional communities now have access to an integrated cancer care service based around a radiotherapy unit. As these services continue to grow, it is essential to appraise patient and carer experience of the care delivered to ensure they can be further tailored to meet the needs of regional communities.

The current study aimed to explore patient and carer experiences of care from a regional cancer centre with specific reference to cancer pain management.

Methods

A qualitative approach was used to develop an in-depth understanding of patient and carer experiences and interpretation of care for pain from a regional cancer service.

Reporting adheres to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ)8.

Setting and sample

The study was conducted at a single comprehensive cancer centre in regional New South Wales (NSW), Australia. This centre is located in an area classified as category 3 using the Modified Monash Model9 and provides inpatient and outpatient radiation and medical oncology, haematology and specialist palliative care services to people living across five local government areas.

The sample was drawn from a larger cohort of participants who consented to be involved in the multi-site stepped wedge cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) Stop Cancer PAIN Trial (‘trial’)10, and their informal carers (‘carers’). This trial tested strategies to implement cancer pain guidelines. Recruitment and data collection occurred during the usual care phase of the trial.

Rather than an aim to reach a particular sample size, all trial participants at this centre were invited to participate in the interviews.

Eligible patients and carers were adults (aged ≥18 years) and capable of providing written informed consent and completing an interview in English. All patients had a current diagnosis of cancer, attended the centre as outpatients during the trial period of August to November 2015, and had reported worst pain over the past 24 hours to be ≥2 on a 0–10 numerical rating scale (NRS) when screened in the outpatient waiting room before a consultation. The trial team approached patients who met eligibility criteria via telephone and invited them to give informed consent to participate.

People were eligible to be included as a carer if a participating patient identified them as providing him/her with substantial emotional and practical support in an unpaid capacity.

Data collection

Data were collected via semi-structured telephone interviews. Interview questions focused on participants’ experience of pain assessment and management and degree of person-centredness and coordination of care.

All interviews were conducted by the trial coordinator (AH), a female registered nurse with palliative care expertise and experience conducting research interviews with people with advanced cancer. The interviewer had telephone contact with participants before the interview while conducting surveys associated with the larger trial. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service. Transcripts were not returned to participants for comment or correction. No field notes were taken during or after the interviews.

Analysis

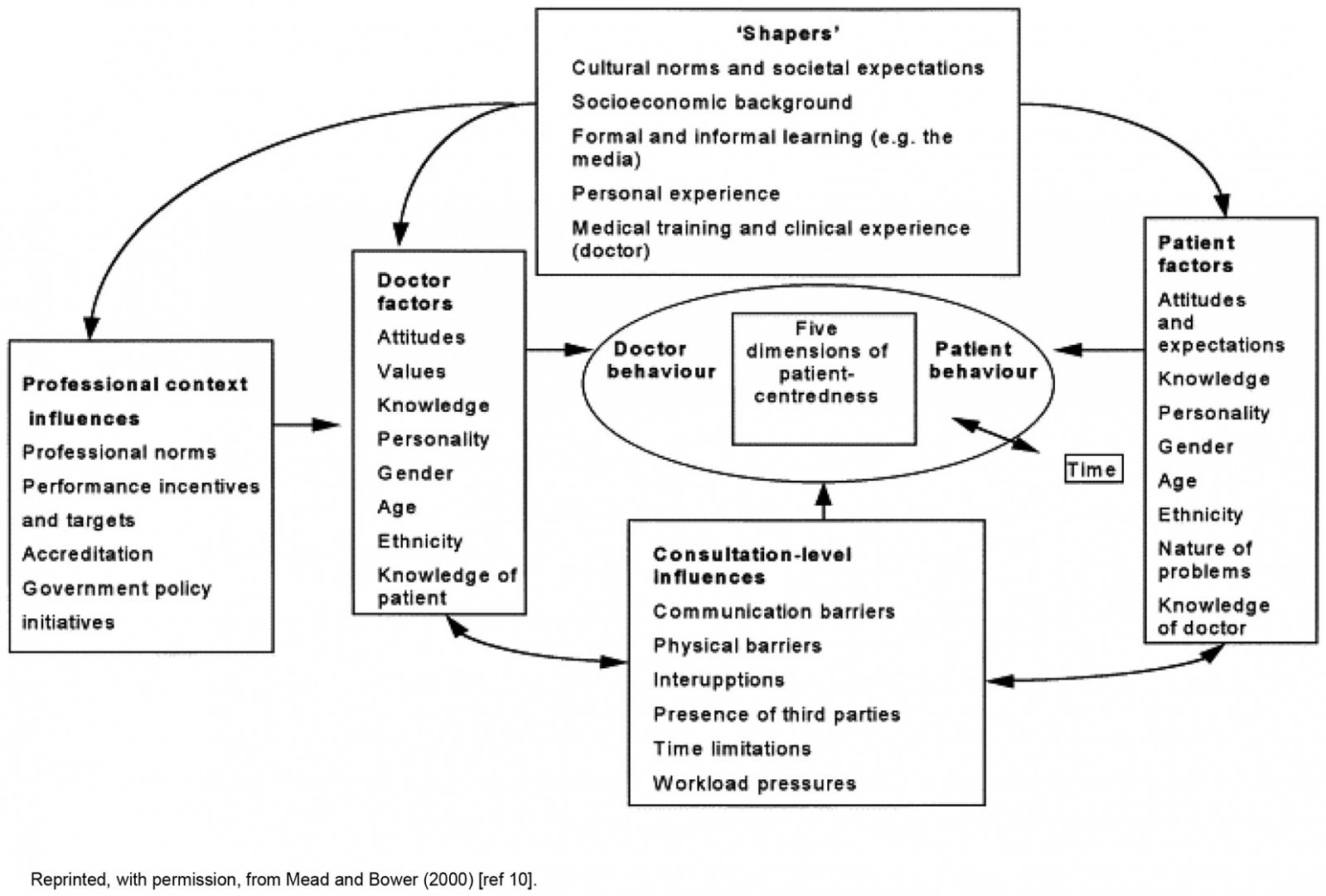

Analysis took a largely deductive approach aimed at building on previous qualitative research on cancer pain management. More specifically, the researchers built on a previous meta-synthesis2 by coding against Mead and Bower’s (2000)11 framework of patient-centred care. This model highlights five dimensions of patient-centred care, namely ‘biopsychosocial perspective’, the ‘patient-as-person’, ‘sharing power and responsibility’, ‘the therapeutic alliance’, and ‘the doctor-as-person’, as well as a range of influential factors (Fig1). Analysis began by coding participant perceptions of pain management against the five dimensions of patient-centred care, and then coded references to the regional setting against the various levels of influential factor. Where content on the regional setting was a poor fit for the framework, codes were created inductively.

To reduce the risk of bias and enrich interpretation, analysis of each interview was conducted by two independent researchers (AR and LE), who then met to agree codes. These researchers had cancer nursing and public health backgrounds respectively. Any disagreements that arose between the reviewers were resolved through discussion, and emerging themes were discussed with a third reviewer (TL).

Data were managed using NVivo v11 (QSR International; https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home).

Figure 1: Factors influencing patient-centredness.

Figure 1: Factors influencing patient-centredness.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the South Western Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/14/LPOOL/479). All participants gave written informed consent.

Results

Eighteen interviews were conducted with 13 patients and 5 carers. Interviews lasted between 10 and 65 minutes (mean 26 minutes). The sample included people with advanced cancer, some of whom were too unwell to complete longer interviews.

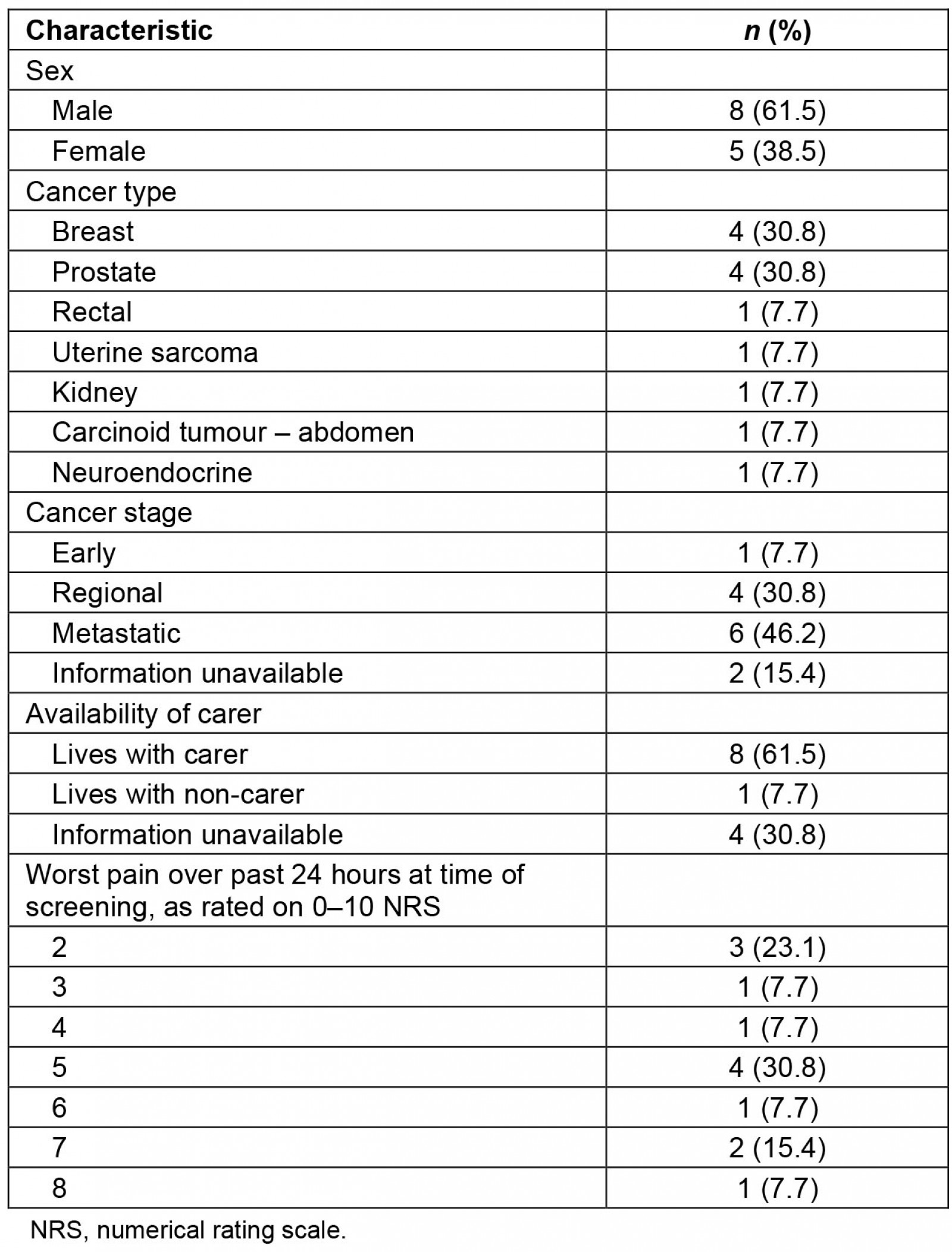

Patient participants’ ages ranged from 56 to 84 years, with a mean of 65.8 years (standard deviation (SD) 19.3). Their ratings of worst pain over the past 24 hours at time of eligibility screening ranged from 2 to 8 on the NRS, with a mean rating of 4.7 (SD 1.9). Other sample characteristics are summarised in Table 1. Carers included three women and two men, all of whom were patient spouses.

Table 1: Characteristics of 13 patients with cancer who participated in interviews on their experience of pain management at an Australian regional cancer centre

Dimensions of patient-centred care

Participants reported experiences relevant to all five dimensions of patient-centred care described by Mead and Bower’s (2000) framework11.

Biopsychosocial perspective: Participants made various references to biological, psychological and social impacts of their pain. Several participants had received pain-related advice from a physiotherapist regarding positioning and mobility. However, participants mostly reported the service focusing on pharmacological management and having to discover non-pharmacological strategies for themselves.

Like if the doctor gives me a tablet and says, you’ve got to take this because you’ve got a … germ in your system and this is an antibiotic that’s necessary to kill it, I’ll take that, that’s not a problem. But for him to say here’s a prescription for a tablet which should help you when you’re in pain, when you’re in pain and you need it, you take it. I had a lot of trouble coming to terms with that. [Doctor’s name] used to say to me, you should take one, now’s the time to take it, and I’d put it off and put it off and put it off until sometimes quite often the pain would ease and get better … not having had it [pain medication], because I would use the TENS machine and the heat packs and the resting, you know, yeah. … [Interviewer: So is that [non-pharmacological strategies] something that you just decided to do independently?] Yes, we decided to do that ourselves. (74-year-old woman with breast cancer)

Patient-as-person: Many participants gave instances of pain management being tailored to their needs based on preferences and responses to side-effects.

He really went into all the aspects of medication and how to control the pain and what was effective and what wasn’t and he said, ‘Now if you find this is not going to work for you, let me know and we’ll find something else.’ He was really terrific. (65-year-old woman with uterine sarcoma)

Sharing power and responsibility: Power sharing and responsibility were most discussed within the context of pharmacological management. A small number of participants reported that they did not feel there was enough discussion or explanation around pharmaceutical pain management. As a result they feared potential side-effects and put up with pain rather than take the prescribed medication, often without telling their doctor.

I’d rather have a bit of pain than feel like a zombie. [Interviewer: So did anyone else, did any of the doctors or nurses or anyone else talk to you about the pain medication and what it might …?] Oh, just the oncologist when she prescribed it said if I was experiencing severe pain to take medication … But I never ever bothered. [Interviewer: Did you have any other information or training, apart from the prescription and the medication?] I don’t think so. (83-year-old man with prostate cancer)

They’d say rate your pain and I’d go, ‘oh it’s probably peaked at about 5 or 6 and at the moment it’s 2’, and they’d go ‘oh right-o – here’s your tablets you know and take these’, and it’s like I didn’t have any option, the medication was just pumped into me. (71-year-old man with rectal cancer)

The therapeutic alliance: Many participants referred to the caring nature of centre clinicians and the empathy and support they showed.

When you’re going through cancer, to have the understanding of your doctors, or you can understand them, and them giving it to you straight; none of this fooling around or going … you know, it’s just upfront, straight, but in a way that it’s kindness and, it’s like, ‘we know’. The whole service there, not just Dr [Name], the receptionist - it’s like ‘we know how you’re feeling and we know what you’re going through’. Even the receptionist said ‘any time you just ask me, I’ll give you a hug’. Do you know what I mean? (55-year-old woman with colon cancer)

The doctor-as-person: Participants reported a high degree of familiarity with their healthcare team, made manifest through informal discussion and personal sharing. This was welcomed by participants as setting them at ease.

Well she’s very approachable and she goes through everything with me pretty carefully, you know, as well. Well when I say carefully she – well we talk about sport most of the time … she’s very approachable and she’s got time, you know, she’s got time to talk to the people who go and see her I think. [Interviewer: Yeah. So do you feel – when you go to see her do you feel better because of that approach?] Yeah I do, yeah. (82-year-old man with prostate cancer)

Factors influencing the patient-centredness of care

Receiving care in a regional setting was perceived to have predominantly positive influences on the person-centredness of care received, with cultural norms flowing through to other levels of Mead and Bower’s (2000) framework11, as outlined below. There were no references to receiving care in a regional setting that did not fit easily to the framework.

Professional context influences: Several patients commented on perceived differences between regional versus urban settings with regard to the former having a heightened sense of community. This was perceived to contribute to a more informal, personable approach to professional practice by health professionals and auxiliary staff at the cancer centre, and the hospital more generally.

I was up there [hospital] last with my mother and one of the nurses asked how my husband was because she knows him. It is a much nicer feeling than having to go to a big sterile hospital. I know they try to make them not that way but a little community hospital has its benefits … [The hospital is] five minutes [from home] which is brilliant, and most of the nurses up there or a lot of the nurses up there are local people that you know and it’s very much a community hospital … and even to the extent of the cleaners and the kitchen staff and all that – they’re all local women or a lot of them are local women … They’ll [gardeners] be working in the garden and people will be sitting out and you’ll often see banter and chat between them [gardeners and patients] because they know each other. That’s something that you don’t get in one of the bigger hospitals. I’ve been in [major city] Hospital and seen the gardener and you might nod at him but that’s probably the extent of the interaction. (66-year-old woman with uterine sarcoma)

Participants commented on ease of access to pain care and attributed this to the proximity of the centre, the availability of home visits and, in some cases, being given mobile telephone numbers by their healthcare team to contact them out of hours. Ease of access was valued not only for convenience, but also because it made participants feel safe.

She [nurse] had a huge influence as far as my confidence as a carer – I always had a telephone contact that I knew I would get on to her and I only had to phone her once and she was back to me in a moment, yeah. (female carer of a 76-year-old man with breast cancer)

Living in a smaller community was also perceived to contribute positively to coordination and continuity of care through virtue of having longstanding relationships with their GP as ‘family doctors’, and there being well-established communication pathways between a smaller number of primary care and specialist providers than might be the case in a city.

Yeah, it works out well because I see the oncologist say one week and then about 10 days later I see the GP [general practitioner], [that’s] the way the cycle works between the two of them. So I’ve only got about a 10 or 11 day period where I’m not in touch with a professional. In both cases they both told me if there’s any problem [they said] don’t let it develop, come and see them or get in touch with them and they’ll organise to see me ASAP … That’s comforting and I’ve been seeing her [the GP] for over 20 years so I know her pretty well. It’s a pity that Area Health are taking over a lot of the little hospitals because that local community feeling is something that you can’t duplicate in a big organisation. (79-year-old man with prostate cancer)

One negative case was presented by a patient–carer dyad who had experienced conflicting advice from their GP and oncologist, with no one clinician taking the lead.

[Interviewer: … how well has pain been managed in [patient]’s case?] So I think on the one hand you’ve got her GP who is always trying to convince her that she will never be pain-free and that she should be willing to accept constant pain, and then you’ve got her oncologist who is saying well you know I’m sure we could do something about this, there’s no reason why you should live in pain … the whole thing has been fragmented, there’s no one person who takes control – so you’ve got her GP, you’ve got her oncologist, you’ll got all sorts of other specialists looking at various things but there doesn’t seem to be any coordination overall. (male carer of a 72-year-old woman with breast cancer)

This carer also voiced the only disadvantage identified from receiving care in a regional setting, namely a long waiting time for accessing a pain specialist.

She needs to be seen I think by the pain clinic, I think it’s called the pain clinic and he [doctor] said ‘I’ll get you a referral’, and then he [doctor] said ‘but don’t hold your breath because it’ll take at least twelve months before they can see you’, so I don’t see what the point of that was! (male carer of a 72-year-old woman with breast cancer)

Doctor and patient factors: Patients’ knowledge of their health professional team and vice-versa was perceived to contribute to the therapeutic alliance and place the team in a more appropriate position to provide emotional support.

They [health professionals] tend to know your history. (66-year-old woman with uterine sarcoma)

Consultation-level influences: The regional setting appeared to reduce physical barriers to consultations in the form of easier appointments, less overcrowding and fewer travel-related problems. Healthcare professionals were perceived to have more time and flexibility when dealing with patients and carers. This made participants feel more valued and at ease with going to appointments.

There's appointment times and the availability of appointments. And that's been excellent … I haven't got one complaint about the hospital or the staff or the people there. They're just wonderful … I am so happy to be here getting treatment where I've had the treatment. I'd have hated to have been [getting treated] in the city. [Interviewer: Are you from the city originally?] Well I've lived in cities, I know what they're like [What's the difference do you think between the country and the city?] Availability of parking to get to places. The ease of actually getting somewhere … Not the overcrowding of sort of consulting rooms and that type of thing … the staff are not under anywhere near, I don't know, from my angle I see them not under the pressure. And they are able to devote their time to you and in a very, very pleasant and lovely way. [Does it feel more personal?] You feel respected and you feel - yeah, respected. (76-year-old man with breast cancer)

Discussion

The current study is the first to explore the perspectives of patients with cancer and their carers regarding pain management when living and receiving cancer care in regional Australia. Participants reported that their care was generally patient-centred, although they would have welcomed greater involvement in shared decision-making regarding pharmacological management and non-pharmacological alternatives. Participants perceived that living in a regional setting conferred advantages to the patient-centredness of care by means of influences at the levels of professional context, doctor–patient relationship and consultation. In general, the regional setting was also perceived to contribute to continuity of care between specialist and primary care providers.

A patient/carer preference and unmet need for non-pharmacological management strategies is among the most consistent findings across qualitative studies to date, regardless of setting and country2,3. Due to time limitations, doctors may sometimes prescribe opioids as a default rather than planning a more holistic approach based on comprehensive assessment12. While clinicians tend to be focused primarily on controlling pain, patients have a more complex and individualised goal of balancing pain relief against medication side-effects based on the relative disability conferred by each within the context of their everyday lives13. Rather than viewing patients’ reluctance to take opioids as a problem with ‘adherence’, medical teams should accept that patients’ unique experiential perspectives make them the ultimate experts on their own pain and should coach them to self-manage using pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies according to their personal preferences and priorities14.

The present study’s finding that participants received and valued a high level of community support in the regional setting is consistent with previous findings of Canadian research on cancer pain and Australian research on cancer more generally conducted with remote patients4,15. The present study extends these previous findings by showing that social networks for patients/carers in an Australian regional setting can include hospital staff, blurring professional boundaries to benefit patient-centredness. Moreover, while participants living in more remote settings may face challenges in travelling for specialist treatment, the regional setting in this study seemed to afford a balance between social support from a close-knit community and easy access to comprehensive cancer services. Indeed, participants viewed specialist care to be accessible on four of the ‘5 As’ of access (ie all dimensions except affordability, which was not mentioned)16. They reported care to be ‘available and accommodating’ in terms of flexible appointments and ample time spent with each patient, ‘acceptable’ in terms of being run by and for the community, and ‘geographically accessible’ in terms of easy travel and parking. Participants also perceived care to have a high degree of continuity between specialist and primary care providers, which is a well-documented challenge in the urban setting17.

Interestingly, participants generally reported a high degree of access to primary and specialist care, despite access to the former often being limited in regional and remote Australia18. One exception was a woman with complex, non-malignant pain who could not access a pain specialist and whose GP and oncologist were perceived to have provided conflicting advice. Although only a single case, this experience is consistent with a lack of specialist pain services in regional Australia19 and documented prevalence of non-malignant pain in people with cancer20. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has since extended government support for telehealth services and prompted a surge in uptake21, increasing access to specialist pain services for people in regional and remote areas that was not available during this study’s project period. An 8-week online pain management program has now also become available for the first time22.

Study limitations

The present study is limited by not including the perspectives of health professionals, especially with regard to workload and time constraints. Also, the sample lacked patients or carers from Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander backgrounds, who constitute a greater proportion of regional and remote populations than of urban one23. Participants were not asked how much experience they had of receiving care from urban oncology services as a basis for comparing the two settings. The study focused on pain, while other problems may be less well served in regional areas24. The study focus was on only one regional cancer centre in NSW, and care has been found to vary between centres and states/territories, at least for anti-cancer treatment and survival25,26. Finally, the unique population distribution and service context of Australia’s regional setting may limit international generalisability, even to countries with similar universal health systems.

Further published research is needed on all kinds of care in the Australian regional setting, including the experience and outcomes of anti-cancer treatment, supportive and palliative care more generally27. The supportive networks highlighted by participants in regional and remote studies to date are of particular interest, given their value at all stages of the cancer trajectory. Future studies are needed to understand how such networks can be optimally mobilised28 and – perhaps – how urban services could learn from regional in terms of activating social support.

Conclusion

While much research has focused on lack of services and poorer outcomes for people with cancer in rural areas, living in an Australian regional setting may offer benefits for the patient-centredness of care for cancer pain and continuity of care. As in studies in urban settings, however, participants in the present study had an unmet need for non-pharmacological pain management. More research is needed to better understand the benefits and trade-offs of cancer care in regional versus urban settings, and how each setting might learn from the other.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded as part of the larger Stop Cancer Pain Trial by the National Breast Cancer Foundation. We would like to acknowledge the personnel and patients at the regional service that formed the focus for this analysis.

References

You might also be interested in:

2004 - A virtual clinic: telemetric assessment and monitoring for rural and remote areas