Introduction

Stunting remains a public health problem that needs to be addressed, including in Indonesia. Globally, there are more than 165 million stunted children aged less than 5 years1, with more than 8.4 million children with this condition in Indonesia2. The WHO has defined stunting as a condition in which a children has a height that is less than the WHO Child Growth Standard median by more than two standard deviations1. Stunting hinders cognitive and physical developments in children3, leads to lower productivity and increases risks of non-communicable diseases such as diabetes and heart disease in adulthood4. Hence, early screening and prompt intervention for stunting in young children is important.

In Indonesia, studies have reported differences in stunting prevalence by socioeconomic status (SES) and location of residence (rural or urban). Children of lower SES or living in rural areas were more likely to experience stunting5,6. The multilayered aspects of stunting (immediate, underlying and basic causes) might contribute to these differences7. The direct causes of malnutrition (dietary intake and pre-existing conditions7,8) have been closely associated with poverty and location of residence9-11. Underlying factors consist of access to basic needs of foods, care for mothers and children, health services and healthy environment12. Basic factors include social and political context, which can influence the availability of resources for children, including those related to health and nutritional status12,13. These factors are closely related to the location of residences and the SES12-14. In Indonesia, several interventions have been targeted to reduce stunting. At the primary health center (PHC, Puskesmas), services related to nutrition and growth are available for nutrition promotion, prevention, screening and management of malnutrition, including stunting15,16. However, evidence on how these programs were associated with stunting reduction is still lacking.

Previous studies have assessed risk factors for stunting in Indonesia12-14. However, there was limited information on determinants of stunting within the different SES or locations (rural or urban) in Indonesia, as well as factors associated with stunting disparities by SES and rural–urban status. The present study aimed to explore whether stunting prevalence and determinants differ by SES and rural–urban status. Further analyses to assess contributors to the persisting differences in stunting prevalence by SES and rural–urban status will be conducted. Hence, better information for policymakers in tailoring targeted intervention programs to reduce stunting in Indonesia can be provided.

Methods

Settings and participants

Publicly available secondary data from the Indonesia Family Life Survey-Wave 5 (IFLS-5) was used in this study. IFLS is a longitudinal, multi-stage survey representing 83% of Indonesia’s population conducted in 13 provinces in Indonesia. In IFLS-5, data from 4090 children and their mothers were available and within biologically plausible values for height. In this study, missing values for several key variables excluded 203 children (4.96%): 115 children due to missing data on nutrition services, 83 children due to missing data on mother’s education, and an additional five children due to missing data on mother’s height. The data analyses were conducted on 3887 children.

Data collection

The data include self-reported children’s health status, obtained from questionnaire-based interviews and anthropometric measurement conducted by a nurse.

Outcome variable

The outcome variable was divided into two categories: stunting (height less than the median by more than two standard deviations) and normal height/tall (height greater than the median by more than two standard deviations). This outcome was calculated using the z-score of height and the corresponding median and standard deviation of the children under the same age based on the WHO anthropometry guideline adopted by the Ministry of Health in Indonesia17,18. The larger z-score corresponds with taller children and better nutritional status.

Independent variables

This study focused on determinants of stunting prevalence and disparities by SES and rural–urban status. Child and maternal sociodemographic characteristics (gender, low birth weight, mother’s stature and mother’s education) were included in this study. Low birth weight was defined as birth weight less than 2500 g, and mother’s short stature was defined as mother’s height less than 145 cm. Dietary habits were also assessed in this study, focusing on two components: unhealthy snack consumption and protein intake. Consumption of protein and consumption of unhealthy snacks were dichotomised into intake less than seven times per week and equal to or more than seven times per week, implying inclusion of these components in the daily diet. Unhealthy snacks in this study include instant noodles, fast food, carbonated beverages, fried snacks and sweet snacks. Information on household sanitation and expenditure were also included in the analyses. SES was represented by household expenditure. Household expenditure was categorised into four quartiles, then the poorest quartile (first quartile, poor) was considered one category, and the other three quartiles another category (second to fourth quartile, non-poor). This constitutes a comparison between the lowest 25% of sample with the remaining 75% of the sample.

For the community-based health services, availability of services associated with children nutrition was included: services in growth and developmental monitoring, additional nutrition aside from breast milk for babies 6–24 months and treatment for malnutrition for children aged less than 5 years. The availability of the three components in three nearby PHCs where the children lived was assessed, as a proxy for nutrition services availability in the community. The variables were assessed in the number of available services, ranging from 0 (no availability in all three nearby PHCs) to 9 (availability of all three services in three PHCs). The availability of nutrition services was further dichotomised based on the availability of all three services in the three nearby PHC (available or not available). Information on children’s health, household conditions, and community-level data on health facilities, were obtained from questionnaire-based interviews.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses were conducted using χ² and independent t-test to assess differences of stunting prevalence by sociodemographic determinants. Logistic regression was used to assess the association between availability of nutrition services, dietary habits and other sociodemographic characteristics with stunting. Stratified analyses were also conducted to assess potential differences of stunting determinants by household expenditure and rural–urban status.

To further assess the contribution of sociodemographic determinants in disparities of stunting prevalence, the regression-based Oaxaca–Blinder decomposition methods19 and the ‘mvdcmp’ extension in STATA v16.1 (StataCorp; http://www.stata.com) were used. The decomposition methods classified the contribution into two parts: differences in characteristics, which represents the differences in characteristics distribution between the two comparison groups; and differences in effects/responses, which represents the influence or association of each covariate in the analyses within the comparison groups20. The differences in effect responses are attributed to differences in the regression coefficients in the analyses. Through these analyses, contributors of stunting disparities by SES and rural–urban communities can be quantified.

Ethics approval

Prior to the survey, the IFLS-5 was approved by the ethics review board of Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia and RAND21. Therefore, ethics review was not required for these analyses.

Results

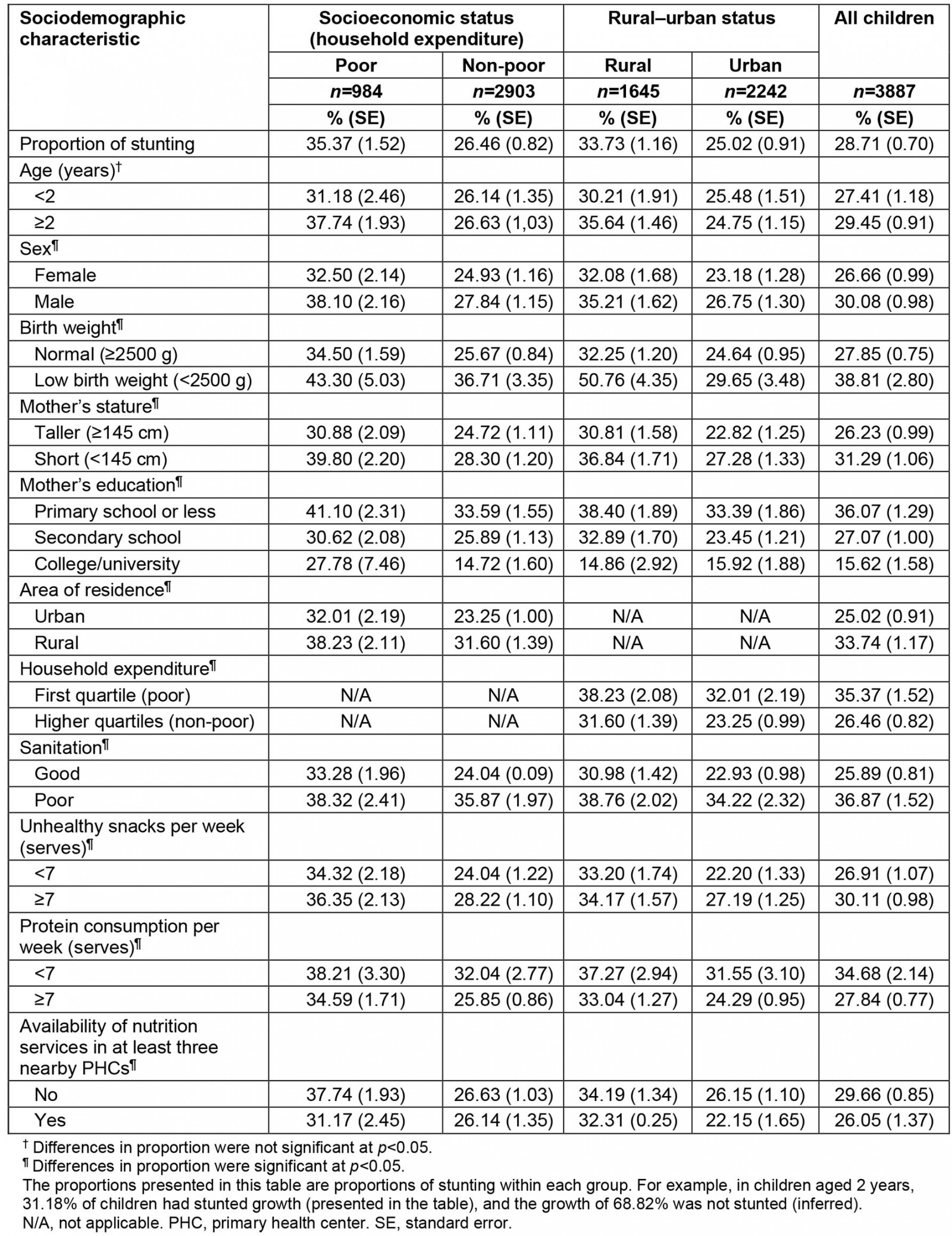

A total of 3887 children were included in the analyses, with 28.7% children categorised as having stunting. Approximately 35.37% of children in the lowest quartile of household expenditure were stunted, compared to only 26.46% in the three higher quartile groups, representing a stunting prevalence gap of 8.9%. The proportion of stunting in rural areas was 33.73% compared to only 25.02% in urban areas, representing a stunting prevalence gap of 8.7% (Table 1).

Table 1: Prevalence of stunting by different socioeconomic characteristics in Indonesia

Differences of stunting prevalence and determinants by socioeconomic and rural–urban status

Differences in stunting prevalence by the different biological, sociodemographic, and dietary and nutritional service factors are presented in Table 1. Higher prevalence of stunting was also observed among male children (30.1% in male v 26.7% in female children (total prevalence by sex, Table 1)). Stunting prevalence was also higher in children with low birth weight, and children with mothers of short stature or with low education level. Children living in rural areas or in areas with less availability of nutrition services also showed higher prevalence of stunting (Table 1). In terms of dietary habits, there were significant differences in stunting: children who consumed unhealthy snacks more frequently, and consumed protein less frequently, had a significantly higher proportion of stunting (Table 1).

Stunting prevalence by household expenditure and area of residence was also assessed. Comparing children with similar risk factors (low birth weight, mothers with short stature, poor sanitation, poor diet) disparities by household expenditure and rural–urban area was still evident (Table 1). In every sociodemographic characteristic, the prevalence of stunting was higher among children of poor families and children living in rural areas, compared to children of non-poor families or those living in urban areas (Table 1). Larger differences in stunting proportion were observed when comparing unhealthy snack consumption among children from poor households (36.35%) with children from non-poor households (28.22%). For children with a lack of availability in nutritional services in their area, there was a higher prevalence of stunting in children from poor households (37.7%) compared to only 26.6% stunting prevalence in the non-poor households. These findings were despite all these children having similar lack of availability in nutrition services in their area. The greatest stunting prevalence was observed among children who had low birth weight, were from poor families (43.30%) or living in rural areas (50.76%). Higher prevalence of stunting was also observed in children with a combination of risk factors. For example, stunting prevalence was more than 35% among poor or rural children who had lack of sanitation, had non-nutritious dietary habits, or with maternal short stature (Table 2).

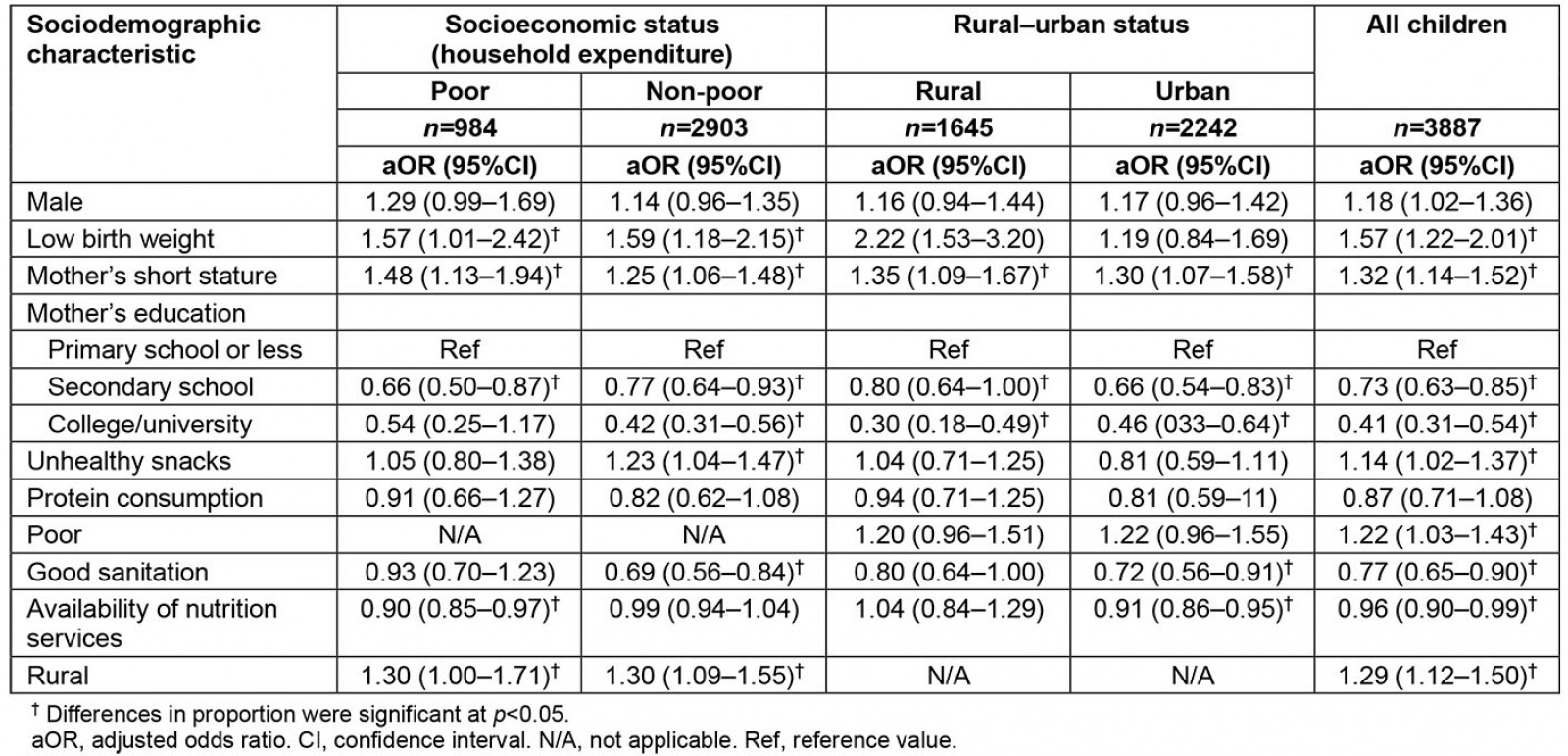

To assess the association of the different factors with stunting in this study, the authors conducted logistic regression for all children, as well as stratifying by household expenditure and rural–urban status (Table 2). For all children, being male, of low birth weight and having a mother with short stature were significantly associated with higher odds of stunting. For the sociodemographic characteristics, having a mother with little education, being from a poor household, having a lack of sanitation and living in a rural area also significantly increased the odds of stunting. Regarding dietary habit, when analyzed for all children, those who consumed unhealthy snacks more frequently had higher odds of stunting than children who consumed unhealthy snacks less frequently (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 1.14, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.02–1.37). Although not significant, protein consumption more than seven times per week reduced stunting. The availability of nutrition services at the nearby PHC proved to be an essential factor in reducing stunting (Table 2). For all children, those living in areas with more availability of nutrition services had lower odds of stunting (aOR 0.96, 95%CI 0.90–0.99).

When stratified by household expenditure, slightly different patterns were observed. In the poor households, availability of nutrition services had significant association in reducing stunting (aOR 0.90, 95%CI 0.85–0.97), while in children from the non-poor families this association was not significant. Meanwhile, in households with higher expenditure, good sanitation reduced stunting (aOR 0.69, 95%CI 0.56–0.84), while unhealthy snack consumption significantly increased with the odds of stunting (aOR 1.23, 95%CI 1.04–1.47). This association was not significant within children coming from poor families. Good sanitation had stronger association among children from non-poor households (Table 2). This finding suggests differences in stunting determinants by household expenditure and rural–urban status.

Table 2: Logistics regression of sociodemographic factors related with stunting

Determinants of stunting disparities by socioeconomic and rural–urban status

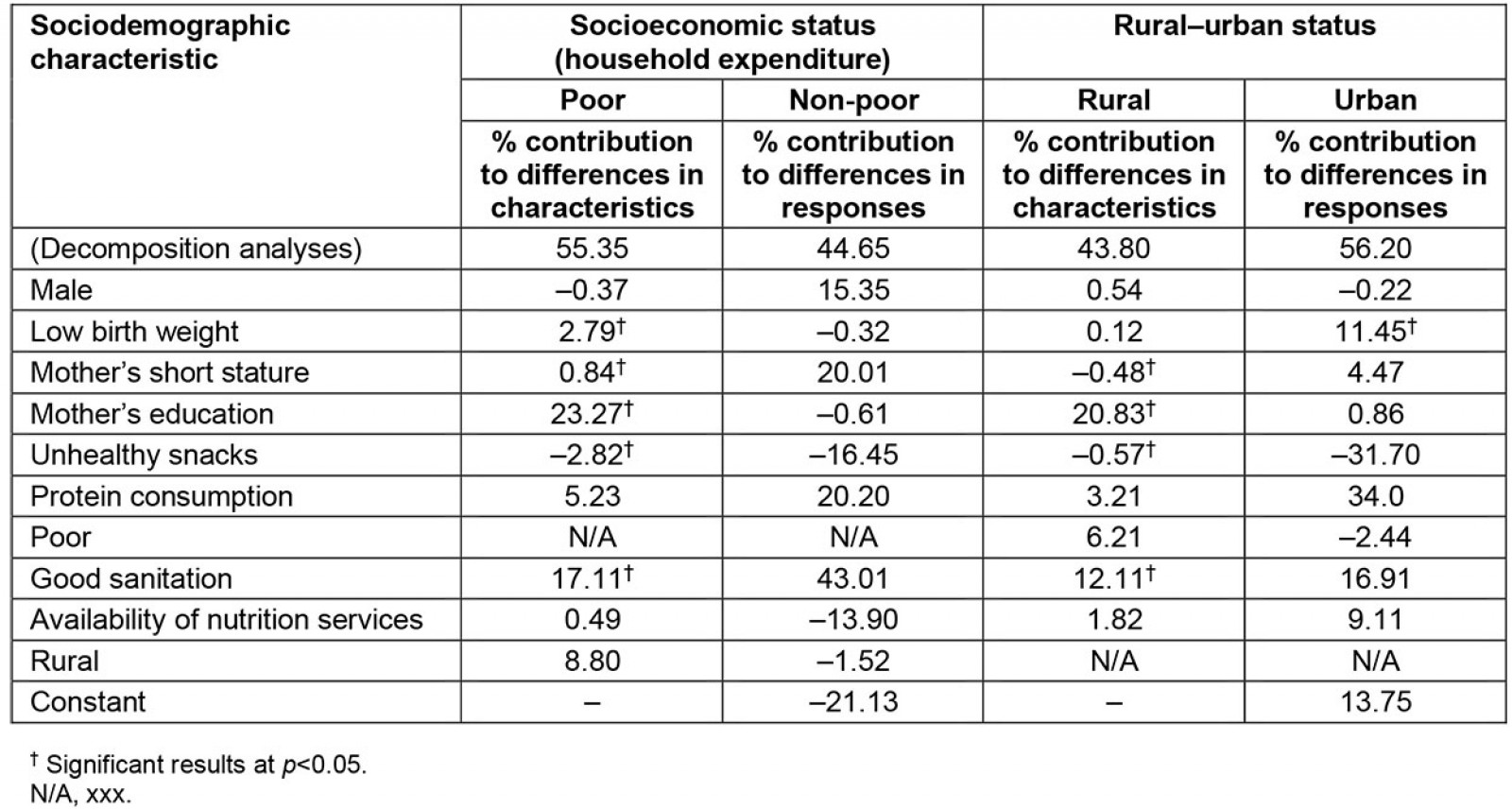

To assess determinants of differences in stunting prevalence by level of SES and rural–urban status, the authors conducted decomposition analyses using the Oaxaca–Blinder methods. Table 3 presents the result from the decomposition analyses, which shows that the differences in stunting were partially attributed to differences in characteristics between children from different levels of SES or rural–urban status. For disparities by household expenditure, it was found that differences in sociodemographic characteristics were the more dominant contributors in stunting prevalence gaps (55.35%). These were mostly due to differences in prevalence of low birth weight, mother’s education, mother’s short stature, unhealthy snack consumption and good sanitation (Table 3). Increasing level of mother’s education in poor families to the level of education of mothers in the non-poor families can reduce the gaps in stunting prevalence by more than 23%. If the proportion of mothers with short stature between the two groups were similar, this would reduce the gap between the poor and non-poor families by 0.84% (Table 3). However, differences in responses (differential effect of factors on poor and non-poor households) was also relatively high (44.65%). This implies that for children who have similar characteristics (eg low birth weight), the possibility to develop stunting is different by level of household expenditure.

For the rural–urban comparison, differences in responses were more dominant (56.20%) in contributing to gaps in stunting prevalence, with low birth weight as the significant contributors in differences of responses. Differences in proportion of mother’s short stature, mother’s education, consumption of unhealthy snacks and good sanitation between rural and urban areas contributes significantly to the gaps of stunting prevalence. This finding implies the importance of prioritising these areas in stunting reduction, particularly in rural areas. The differential effects of unmeasured variables (ie variables not included in the decomposition analyses) were represented by the ‘constant’, which was available for differences in responses. In the analyses, unmeasured variables were shown to have substantial contribution to the gap in stunting prevalence due to responses/effects. For stunting differences by SES, the unmeasured variables contributed to –21.13% difference in response. The negative values imply that if the unmeasured variables were similar between the poor and non-poor groups (in proportion and responses of the characteristics), the gap in stunting prevalence would have been larger between the poor and non-poor group. For stunting prevalence gap by rural–urban status, the unmeasured variables accounted for a 13.75% difference in response. Making the condition of unmeasured variables between rural and urban similar would decrease stunting prevalence by 13.75%.

Table 3: Decomposition results of the gap in stunting prevalence, Indonesian Family and Life Survey 2015

Discussion

This study corroborates previous findings on several key biologic and sociodemographic determinants of stunting. These factors include being male, having low birth weight and mother’s short stature22-24. Further additional evidence on the association of sociodemographic factors with stunting was also emphasised – in particular, the higher stunting prevalence in rural areas or in children living with inadequate sanitation and poor households. Previous studies have signified the importance of these factors as underlying factors of stunting24-27. What this study adds is information on differences in the determinants of stunting by level of household expenditure and rural–urban status. Furthermore, determinants of stunting disparities in Indonesia are also shown.

Differences of stunting prevalence and determinants by socioeconomic and rural–urban status

In the stratified analyses by household expenditure and rural–urban status, there were slight differences in factors associated with stunting prevalence. Even with similar risk factors (low birth weight, mothers with short stature, poor sanitation, poor diet), being poor or living in a rural area were related to higher prevalence of stunting. This was observed across most sociodemographic factors analysed in this study. This finding is in line with previous studies highlighting the concentration of stunting among poor households or in rural areas28-30. However, this study adds to the current literature by conducting further analyses on predictors on stunting disparities by both socioeconomic status and area of residence. Children from advantaged families (living in urban areas or with families of higher household expenditure) benefited from the availability of good sanitation and better maternal education status.

The stratified analyses conducted in this study signify the importance of nutrition services in stunting reduction, mainly among children from poor families. Access to nutrition services reduces stunting among these children. This can be explained by the limitation of resources among the poor as well as lower level of maternal education. Therefore, availability of nutrition services for children from poor families were important in improving their condition31. In Indonesia, nutrition services at a PHC include monitoring of children’s growth and development, provision of additional nutritious food for children aged 6–24 months, and treatment of malnourished children aged less than 5 years. Previous studies have also reported the effectiveness of these services, generally conducted through Posyandu (a volunteer-staffed integrated health service post affiliated with PHC)32,33. Health services availability, including nutrition services, also need to be improved, particularly in rural and remote areas in Indonesia. This could be done by providing financial and non-financial incentives to health workers serving disadvantaged areas34.

Studies evaluating educational intervention on nutrition also showed promising findings. Children from families receiving nutritional educational programs performed better in nutritional status measurement35,36. Several studies have also reported the effectiveness of community programs in reducing stunting prevalence36,37. Hence, availability of nutrition services in the form of nutritional assistance or education become substantial factors to improve nutrition, particularly in these poor children.

With their better SES, children in families with greater household expenditure have the resources for a variety of dietary alternatives. Unhealthy snack consumption with high salt and sugar increased stunting prevalence, particularly in children from more privileged families. This result indicates the importance of good dietary habits: reducing unhealthy snack consumption and increasing intake of basic nutrients, particularly protein. Snacks high in sugar or salt generally have low nutritional value and high energy content. Their consumption can displace consumption of nutritious foods, which are important for children’s growth and development38-40. Previous studies also signified the role of diet quality in reducing the risk of stunting41-43. A higher score of diet diversity by one point contributes to lower stunting risk by more than 10%43,44. The diet of Indonesian children is dominated by carbohydrates from staple food, fibre from vegetables and legumes and protein from eggs. Nevertheless, the diet lacks fruits as sources of vitamin and fibre; meat, poultry and fresh fish as sources of protein; and dairy products as prime sources of calcium45. Therefore, promotion of a diverse diet rich in protein, fruit and vegetables is important for these children whose families have the resources to adopt healthy dietary habits.

This study also found the importance of good sanitation on stunting reduction. The finding was consistent across the different groups and was also a significant predictor in gaps of stunting prevalence. The finding is in line with previous reports showing that access to good sanitation was found to be an important stunting predictor27,46. Good sanitation prevents children from infection, particularly diarrhoea, a condition that hinders absorption of nutrients and general development24,47. Improvement of sanitation is important in a stunting reduction program, as a sensitive and effective intervention.

Determinants of stunting disparities by socioeconomic and rural–urban status

The Oaxaca–Blinder decomposition analyses is a regression-based analyses comparing two groups. The present study compared poor with non-poor households, and rural with urban areas. For each group, stunting was estimated by a function of covariates and its coefficients. The gap of stunting prevalence between the two groups can be classified as differences in characteristics or endowment (explained components or characteristics effects), and differences in coefficients or effects (unexplained components or coefficient effects)20,48-50. For example, when looking at rural–urban differences, the differences in characteristics reflect a counterfactual comparison of the differences in outcomes from the rural group perspective – the expected difference if children in rural areas were given the distribution of covariates of the children in urban areas. The differences in effects reflect a counterfactual comparison of outcome if children from urban areas experienced the same behavioral response or effect as children in rural areas.

In the decomposition analyses, assessment of the factors related to gaps in stunting prevalence by SES and rural–urban status were further explored. The analyses showed the different proportions for low birth weight, mother’s short stature, mother’s education, unhealthy snack consumption and children living with good sanitation were significant contributors to the gap in stunting prevalence by SES. Similar findings were also observed in rural–urban differences, except for low birth weight, which was not statistically significant in contributing to the rural–urban gap in stunting. Differences in distribution of mother’s education and sanitation were shown to be the most dominant factors. These findings were in line with previous studies, which underscores the importance of maternal education and sanitation in stunting reduction51,52. Improvement of mother’s education and sanitation within poor and rural communities will reduce the gap in stunting prevalence by more than 30%.

The assessment of differences, although not significant, showed that sanitation and dietary habit (protein and unhealthy snack consumption) were the highest contributors to stunting disparities. The analyses also showed the importance of unmeasured variables (represented by the constant). These unmeasured variables might include underlying factors contributed to stunting that were not measured in this study. These include number of siblings, parity, breastfeeding53, and contextual factors including food price and food security54.

The assessment of differences in characteristics and differences in responses (effect) is equally important as the basis for further intervention. For example, with the significant contribution of sanitation in disparities by SES and rural–urban status, improving the sanitation condition in poor and rural communities to match the condition in non-poor and urban communities will reduce stunting gaps by more than 10%. Meanwhile, with high contribution of dietary factors due to differences in responses, reduction in unhealthy snack consumption and increase in protein consumption will not be sufficient to reduce stunting disparities. The impact of these factors was weaker in poor and rural communities. However, implementation of programs to improve behaviour and awareness regarding dietary pattern, particularly in urban areas and non-poor households, might be a more effective approach.

Study limitations and strengths

This study contributes to the knowledge of stunting disparities by SES and rural–urban status in Indonesia. However, there were several limitations of the study. First, the cross-sectional study design of IFLS-5 limited the ability to infer causation. Second was the possibility of bias due to the self-reported nature of several variables as well as unmeasured confounding. In addition, the nutrition services were assessed based on availability in nearby PHCs. Information about whether the respondent accessed or utilised the nutrition services was limited.

Despite these limitations, this study provides theoretical and practical contribution to stunting disparities in Indonesia. From a theoretical perspective, this study adds to the body of knowledge in stunting disparities and its determinants in Indonesia. From a practical perspective, the slightly different determinants of stunting by level of household expenditure and rural–urban status indicate the importance of different approaches in addressing stunting. Based on the present findings, children from the poorer families may benefit from programs providing additional resources (eg nutritional assistance and nutrition services) to reduce stunting. The implementation of several pro-poor programs in Indonesia might need to be directed to also cover stunting reduction and improving access to PHCs. This could be followed by a large education campaign for all children about healthy eating, to reduce unhealthy snack consumption and increase diet quality. Previous studies have reported the effectiveness of educational campaign in improving dietary diversity which can improve nutritional status in children55,56. Improvement of sanitation will also be important, particularly for disadvantaged children. The simultaneous combination of these steps could reduce stunting and improve children’s general health status in Indonesia.

Conclusion

This study showed a persistent gap in stunting prevalence by SES and rural–urban status. The stunting prevalence was higher among children from poor households and children living in rural areas. From the stratified logistic regression, there were slight differences in factors associated with stunting by household expenditure and rural–urban areas. For all children, mother’s short stature and low education (primary school or less) were consistent risk factors of stunting. Meanwhile, for children from poor households, availability of nutrition services and living in urban areas were additional factors related to reduced odds for stunting. Consumption of unhealthy snacks and lack of good sanitation increased the odds for stunting in children in non-poor households. For urban areas, good sanitation and availability of nutrition services reduced the odds for stunting. In the decomposition analyses, several key factors contributing to stunting disparities were identified. Low birth weight, mother’s short stature, mother’s education, unhealthy snacks and good sanitation were shown to be significant contributors to stunting disparities by SES and rural–urban status.

Based on these findings, targeted and effective intervention tailored to address specific determinants of stunting within groups is needed. The significant association between maternal level of education and stunting for all groups of children highlights the importance of improvement in maternal education to reduce stunting, as well as nutritional education for all mothers. Specifically for children from poor or urban families, improvement in the availability of high-quality nutrition services is needed for stunting reduction. Improvement of sanitation and reduction of unhealthy snack consumption could also reduce stunting disparities by SES and rural–urban status in Indonesia.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Indonesian Family and Life Survey that has provided access to the data. IFLS-5 was a collaborative effort of RAND and Survey Meter. Funding for IFLS-5 was provided by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute for Child Health and Development, and grants from the World Bank, Indonesia and GRM International, and from the Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.