Introduction

The configuration of the Australian rural health workforce continues to receive attention with regard to availability, recruitment, retention and scope of practice as strategies to improve care1. Significant policy initiatives have been implemented to ensure people in rural and remote areas have appropriate access to health services, with increasing interest in the role allied health professionals can play in the wider rural health workforce2,3. Previously the focus has centred on pharmacy and physiotherapy, with limited data on osteopathy.

Australian osteopaths are university-trained, primary contact, government registered health professionals – their registration is consistent with that of other Australian health professionals such as physiotherapists and chiropractors. The scope of practice of Australian osteopaths, although not defined in law, focuses on addressing disorders of the musculoskeletal system through manual therapy and other interventions (including exercise and ergonomic advice)4. Australian osteopaths are trained to undertake primary medical (eg cranial nerve examination) and musculoskeletal assessments, and liaise with other health professionals when needed4. The vast majority of Australian osteopaths practise in the private setting, managing private-paying, worker’s compensation and traffic accident patients4.

In the rural context, over 64.1% of rural New South Wales general practitioners (GPs) referred patients to osteopaths or chiropractors, with over 23% referring to these professionals at least once a month5. A current challenge facing the Australian osteopathic profession is the unequal distribution of practitioners6, with most osteopaths (58.2%, n=1485) practising in Victoria7. Notwithstanding, there is little research exploring how Australian osteopaths practise in rural or regional settings. In response to this gap, the aim of the current work was to profile the demographic, practice and clinical management characteristics of Australian osteopaths who identified their primary practice location as rural or remote.

Methods

This study is a secondary analysis of data derived from the Australian osteopathy practice-based research network (PBRN) – the Osteopathy Research and Innovation Network (ORION) Project (http://www.orion-arccim.com)4,8.

Sample

A total of 992 osteopaths provided a response to the 27-item ORION practice survey between July and December 2016. At the time of data collection, this represented 49.1% of the profession in Australia4. Details about the research design, sample and baseline characteristics are described elsewhere4.

Questionnaire

Demographic characteristics included practitioner age, gender, highest osteopathy qualification and duration of working in osteopathy practice. Practice characteristic items related to average patient care hours and average patient visits per week, health professionals co-located in the same practice, receiving/sending referrals, and use of diagnostic imaging. Clinical management items included frequency of treating specific body regions, patient populations and use of osteopathy techniques. Participants also nominated whether their practice location was in an urban, rural or remote setting.

Statistical analyses

‘Rural’ and ‘remote’ responses were combined into a single response (rural) and analysed as a dichotomised variable with ‘urban’ the alternative response. Inferential statistics (independent t-test and χ2 test) were used to identify significant demographic, clinical and practice characteristics. Unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) (and confidence intervals) were calculated for χ2 statistics and effect sizes for independent t-tests where appropriate. Significant exposure variables (p<0.20) were then entered into a multiple logistic regression model. Using backward stepwise elimination, variables significantly associated with practising in an urban or rural location were identified. Adjusted ORs (AORs) and their 95% confidence intervals were calculated with α set at p<0.05. Descriptive and inferential statistics were generated using JASP v0.9.2 (JASP-Stats; https://jasp-stats.org) while the regression model was generated using SPSS v25 (QSR International; http://www.spss.com).

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was provided by the University of Technology Sydney (# 2014000759). All participating osteopaths provided informed consent.

Results

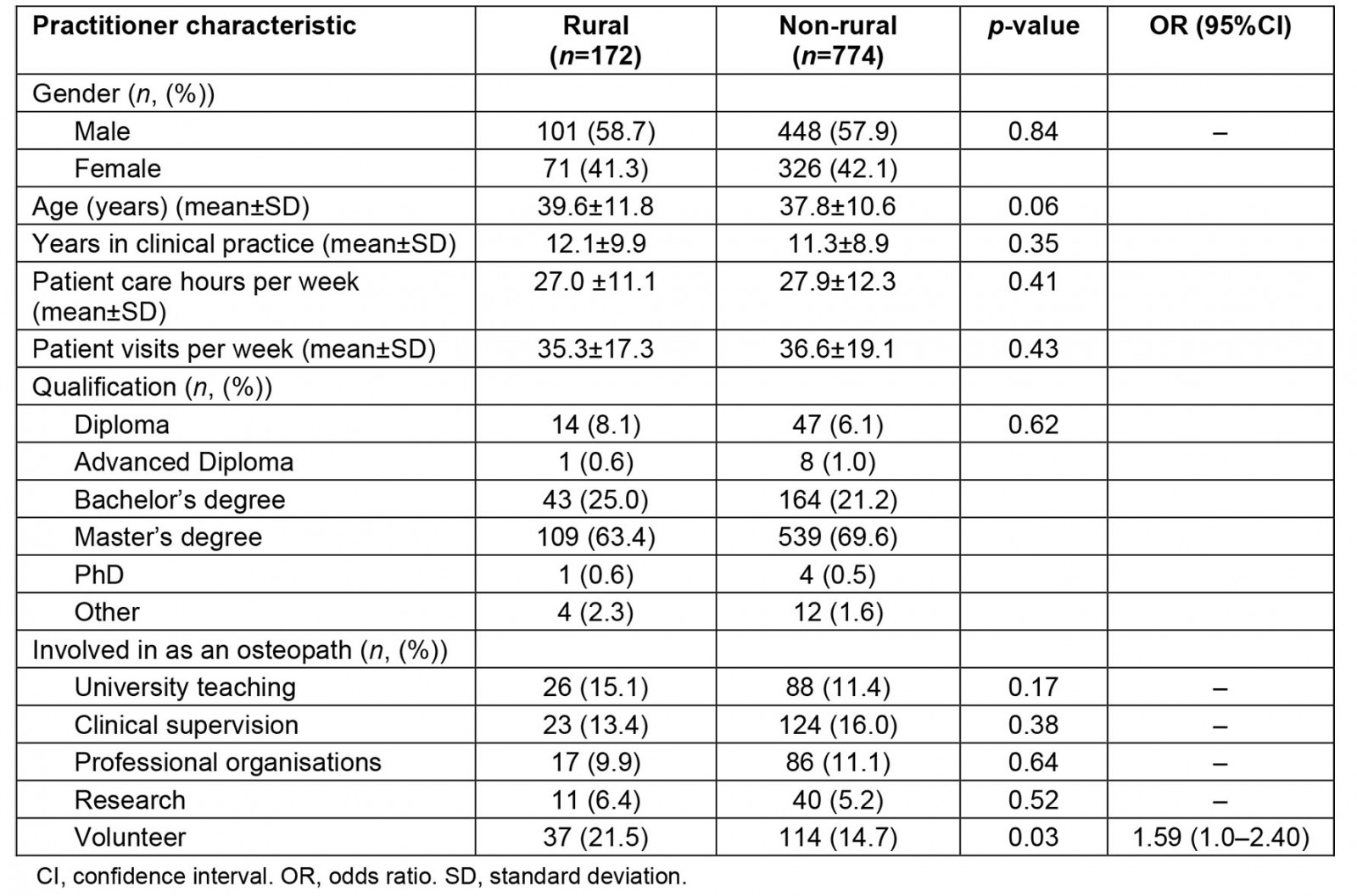

Of the 992 responses to the ORION practice questionnaire, 18.3% (n=172) identified as practising in a ‘rural’ or ‘remote’ location, with 46 (n=4.6%) participants indicating they practised in both urban/rural and rural/remote locations. Osteopaths practising in a rural location were mostly male (58.7%) with a Master’s degree (63.4%) (Table 1). Osteopaths practising in rural locations were more likely to report volunteering as an osteopath (OR=1.59) compared to osteopaths from non-rural locations (Table 1).

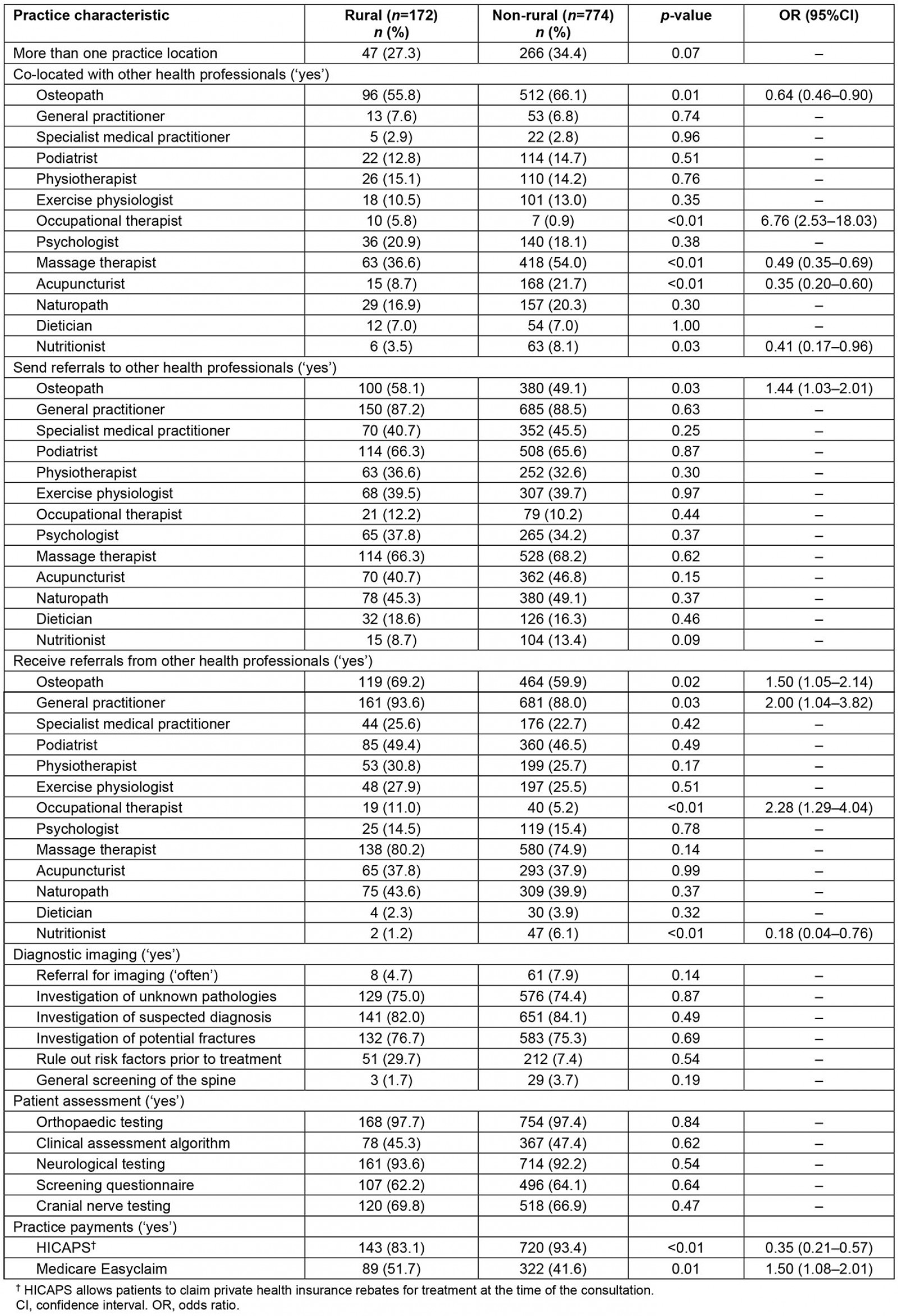

Practice characteristics of the participating osteopaths are described in Table 2. Australian osteopaths in rural locations were less likely to be co-located with another osteopath (OR=0.64), but more likely to report being co-located with an occupational therapist (OR=6.76), compared to osteopaths in non-rural locations. Compared to osteopaths practising in urban locations, osteopaths in rural areas were more likely to refer patients to other osteopaths (OR=1.44) and receive referrals from GPs (OR=2.00). Osteopaths in rural areas were more likely to process government rebates (Medicare EasyClaim) for their patients (OR=1.50), but less likely to process private health insurance rebates (OR=0.35) at the time of consultation (HICAPS) compared to osteopaths in urban areas.

Australian osteopaths in rural locations were more likely to treat patients aged 65 years or older (OR=2.13) and treat Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (OR=18.35) compared to urban-based osteopaths (Table 3). Osteopaths in rural locations were less likely to treat non-English-speaking patients compared to osteopaths in urban areas (OR=0.14).

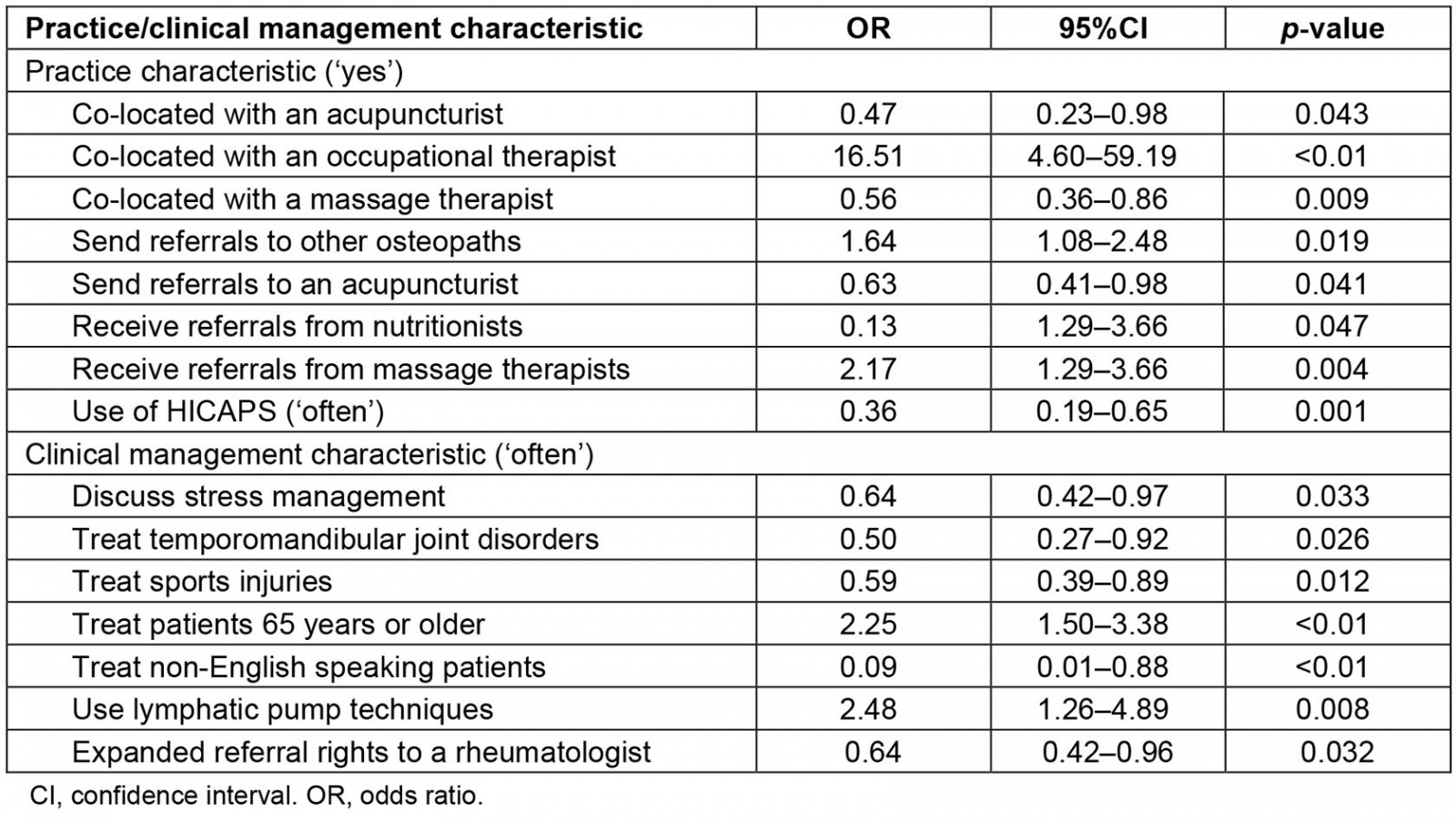

The backwards stepwise logistic regression analysis (Table 4) indicates that osteopaths practising in rural locations were less likely to be co-located with an acupuncturist (AOR=0.47) or massage therapist (AOR=0.56), compared to urban-based osteopaths. Osteopaths in rural areas were more likely to send referrals to other osteopaths (AOR=1.64) and receive referrals from massage therapists (AOR=2.17) compared to urban-based osteopaths. HICAPS was less likely to be used by rural osteopaths compared to urban osteopaths (AOR=0.36). Compared to their urban counterparts, rural osteopaths were more likely to treat patients aged 65 years or older (AOR=2.25) and use lymphatic pump techniques (AOR=2.48), but less likely to discuss stress management (AOR=0.64), sports injuries (AOR=0.59) or treat non-English speaking patients (AOR=0.09).

Table 1: Practitioner characteristics of Australian osteopaths who reported practising in a rural or remote location

Table 2: Practice characteristics of Australian osteopaths who reported practising in a rural or remote location

Table 3: Clinical management characteristics of Australian osteopaths who reported practising in a rural or remote location

Table 4: Adjusted odds ratios for significant practice and clinical management characteristics of Australian osteopaths who reported practising in a rural or remote location

Discussion

Our secondary analysis of data from the Australian osteopathy PBRN identified that 18.3% (n=172) of our sample who practised in rural or remote settings, osteopaths were more likely to be male and hold a Master’s degree. They were more likely to often treat patients over the age of 65 years and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and less likely to use HICAPS and treat non-English-speaking patients.

Australian osteopaths who practised in rural locations were more likely to report treating older patients (age >65 years) than colleagues in urban locations. This association may be a reflection of the demographics of rural populations: over one-third of older Australians live in rural areas compared to just under a quarter of Australians aged less than 65 years in urban areas9. Further, musculoskeletal complaints are more likely to be prevalent in older Australians compared to younger people10 and this may result in more older patients seeking osteopathy care. Older patients are more likely to be referred to an osteopath by their GP compared to other age groups11, with a similar finding observed in rural New South Wales GP referrals to osteopaths and chiropractors5. Osteopaths therefore play a significant role in managing the musculoskeletal health of older patients in rural communities.

Patients were more likely to be referred from massage therapists to osteopaths who practise in rural locations, compared to osteopaths in urban locations. This association may be the result of three factors: established referral relationships between osteopaths and massage therapists in rural communities12, proximity of practice locations close to or within the same community12,13 and/or rural populations being more likely to seek complementary and allied health services for musculoskeletal complaints, compared to urban populations14,15. Compared to their urban counterparts, osteopaths in rural areas were also more likely to refer to other osteopaths, even though rural-based Australian osteopaths are 40% less likely to work in a practice with other osteopaths. It may be that the practices of these osteopaths are geographically located within close proximity13, and have similar practice interests (eg paediatric practice), where referral to another osteopath may be beneficial to the patient. How and why patients are referred to other osteopaths in this context presents an interesting avenue for future research.

Australian osteopaths in rural locations were less likely to use HICAPS for processing private health insurance claims, compared to urban-based osteopaths. Lower utilisation of HICAPS may be related to the lower uptake of private health insurance in Australian rural and remote populations16,17, and it highlights the possibility of out-of-pocket costs for osteopathy care in these settings. Given this potential, exploring why patients in rural settings choose osteopathy care over other available health services warrants additional investigation18. Further research investigating the role of osteopathy in reducing the burden of disease associated with musculoskeletal conditions in rural populations is also warranted.

Limitations

There are several limitations associated with this study including the self-reported nature of data collection, recall bias and social desirability bias. Dichotomisation of several variables in this analysis, particularly related to manual therapy interventions and patient presentations, may have resulted in a loss of nuance in the frequency of use of interventions or presentations. Given dichotomisation was used to highlight interventions and presentations that were commonly used or encountered in practice, we do not believe this affected the analyses performed.

Conclusion

Australian osteopaths practising in rural locations were more likely to engage in referrals with a range of other health professionals and report treating older patients, compared to urban-based colleagues. The current data are valuable in highlighting the role that osteopathy currently plays in the rural health workforce. The findings could inform continuing professional development for osteopaths working or planning to work in rural settings. Rural osteopaths may be able to advocate for increased representation within professional associations, and in developing health policies that are able to cater for rural Australia. Further research exploring the level of awareness about osteopathy, the range of care osteopaths can provide and the accessibility of osteopathy care among rural populations is warranted for a better understanding of ways in which the osteopathy profession can contribute to improving the health of rural Australians.

Funding statement

The ORION project is funded by Osteopathy Australia. The funding source had no influence upon the design of the study, in data collection, analysis and interpretation or in writing the manuscript. The research reported in this article is the sole responsibility of the authors and reflects the independent ideas and scholarship of the authors alone.

Competing interests

The authors report no competing interests in relation to this article.