Introduction

Disasters significantly affect communities, economies and healthcare institutions globally. The United Nations Office of Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) published a report in 2020 stating that over the past 20 years (2000–2019) there have been 7348 reported disasters worldwide, with 1.23 million deaths, 4.03 billion people affected and a total of US$2.97 trillion dollars in economic losses1. This number of reported disasters is significantly elevated from the previous 20 years (1980–1999)1. Increasing effects of climate change, disaster awareness and reporting of disasters may be factors contributing to the increase in the number of disasters reported2.

There is no universally accepted definition of what constitutes as a disaster; however, most definitions describe disasters as extreme events that cause widespread damage (structural/material, human, environmental, economic and any combination of these) and have the ability to overwhelm resources. For this scoping review, the authors have chosen to define a disaster as:

A serious disruption of the functioning of society, causing widespread human, material or environmental losses which exceed the ability of affected society to cope using only its own resources3.

In rural and remote areas where resources are limited, disasters further disrupt the capacity of the health system to anticipate, cope and adapt4. Some challenges associated with rural and remote areas include geographical distance from major cities or towns, greater distances to tertiary facilities or specialists, organisational limitations including size and composition of healthcare teams, underresourcing and reduced infrastructure including roads of varying quality and increased susceptibility to extreme weather. These challenges are unique to rural and remote areas and all influence healthcare delivery and the health of individuals living in these regions5,6. With approximately 44.2% of the world’s total population residing in rural areas, it is important to understand what occurs in health care in this context during disasters7.

During disasters, healthcare facilities are relied upon to provide vital assistance to the community where nurses are at the forefront of providing patient assessment and management. However, in response to a disaster, nurses’ focus shifts from the individual patient to a whole-of-organisation focus, to facilitate the surge and influx of incoming patients8.

Nurses’ roles in disaster response have been discussed many times in the literature, with a focus on nurses working in the emergency department in metropolitan areas9-12. There has also been a large focus on nursing staff preparedness in disaster management and response13-18, and willingness to attend work in a disaster19-21. Some literature written in these domains focuses on the rural and remote context, but few focus on the nurses’ experiences in disasters. Insight into the experience of rural and remote nurses in disaster response could lead to identification of areas for future research.

Rural nurses are positioned in a unique way when compared to their urban and metropolitan counterparts. Often, a nurse may be the sole clinician available at a health facility, with other medical personnel only being available ‘on call’6. Availability of multidisciplinary staff may depend on the health needs of the community, the context of practice (ie distance from tertiary referral centres) and budgetary restraints. These in turn increase the scope of practice of rural and remote nurses, requiring them to broaden their range of clinical skills, which may result in a ‘we’re it’ attitude and generalist approach6,22. This is in stark contrast to urban and metropolitan areas, where health services and specialists are often available 24 hours a day6. Challenges in rural and remote areas include restricted access to resources, together with the multi-modal positions that rural and remote nurses frequently occupy, are brought to the fore when incidents involving multiple patients have the ability to overwhelm local resources and capabilities in a short period of time23. This is further accentuated in disaster situations where business is not ‘normal’, leading to a further increase in the demand for resources.

The purpose of this article is to provide an overview of the existing literature on the experiences of rural and remote nurses during disaster response.

Methods

This scoping review was guided by Arksey and O’Malley’s methodological framework for conducting scoping reviews24. Their five-stage process includes identifying the research question; identifying relevant studies; study selection; charting the data; and collating, summarising and reporting the results24. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist was used to guide the reporting of this review25.

Grant and Booth state that ‘this type (scoping) of review provides a preliminary assessment of the potential size and scope of available research literature. It aims to identify the nature and extent of research evidence’26. This was relevant in the adoption of a scoping review as opposed to other types of review as it allowed for the size and type of literature on the topic to be explored. Given an aim of this review was to explore and identify the types of available evidence in the field of rural and remote nurses in disasters, a scoping review aligned with the aims of this manuscript. The limited evidence of what nurses do in rural and remote settings during disasters further strengthened the rationale for choosing a scoping review design.

Identifying the research question

The research question that motivated this review arose from the need to understand what nurses working in rural and remote areas do and experience during a disaster. The following question guided the scoping review: ‘What are the experiences of rural and remote nurses during a disaster?’.

Identifying relevant studies

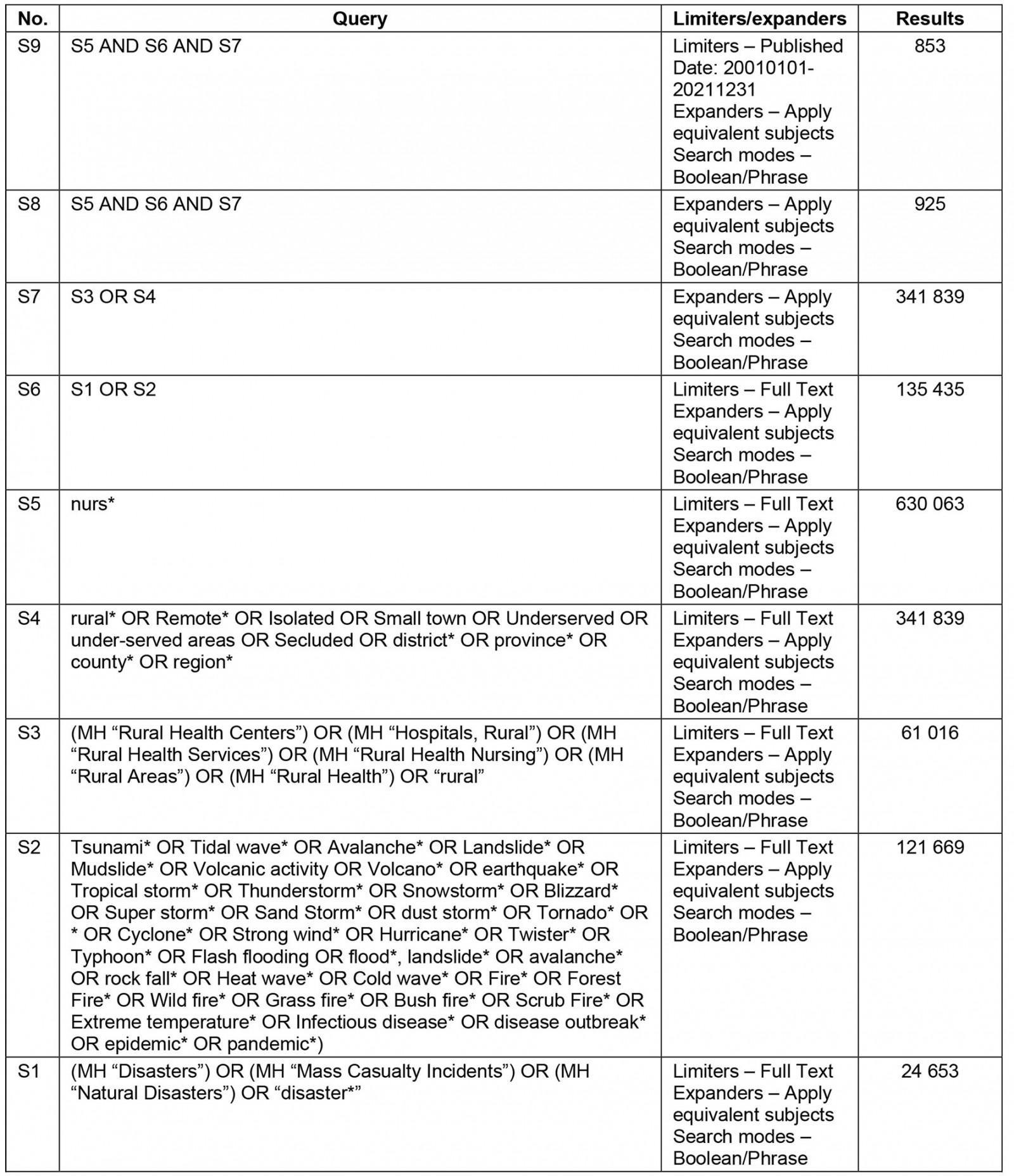

A preliminary search of MEDLINE and CINAHL databases was undertaken to refine MeSH terms and key words. These MeSH terms and key words were then developed into a full search strategy that was applied to the search of all intended databases, with modifications (eg truncation symbols) to suit the intended database. An example of the full search strategy using CINAHL is provided in Table 1. This search strategy was replicated across the other databases (CINAHL, MEDLINE, Scopus, Cochrane, Joanna Briggs Institute, Embase) in March 2021.

Table 1: Search strategy, CINAHL, March 2021

Study selection

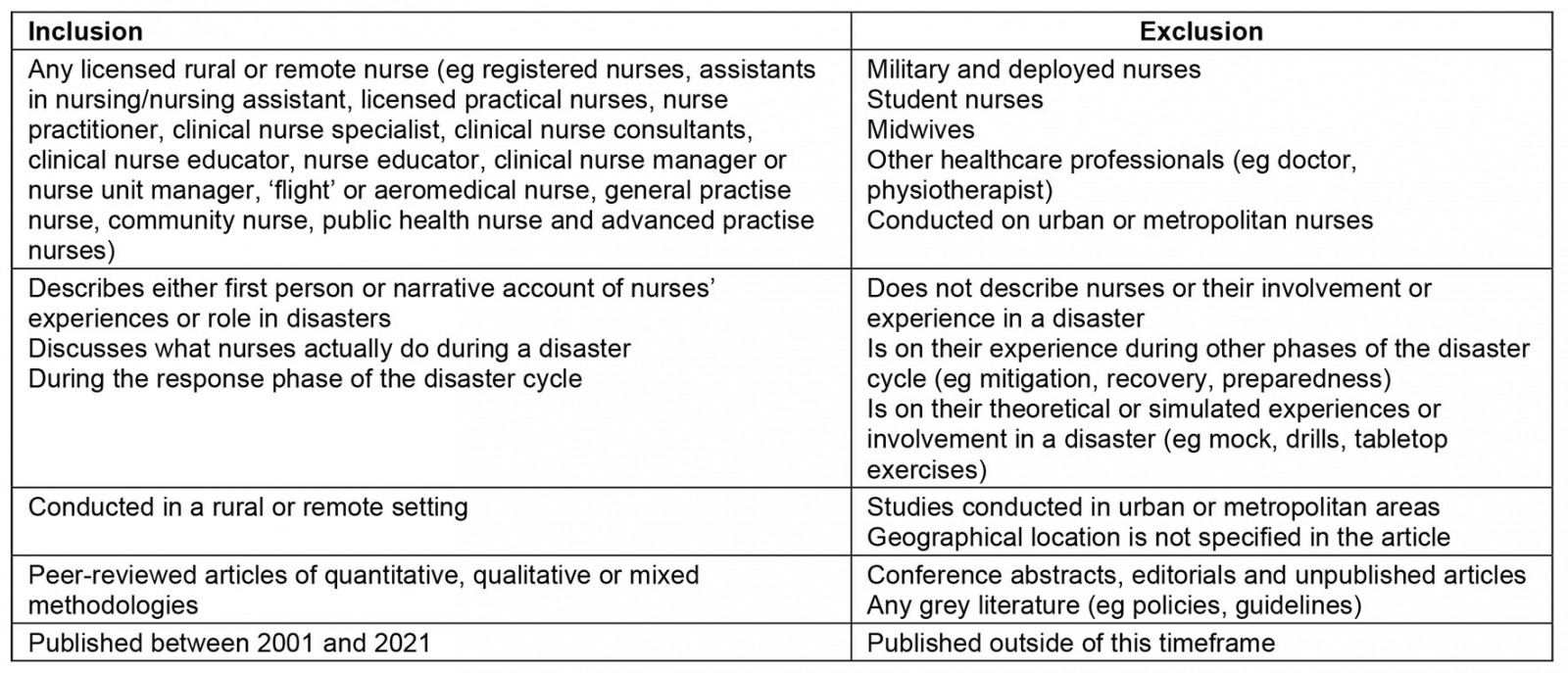

To guide this review, inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed (Table 2). Articles that discussed registered/licensed nurses identified as working in rural or remote areas and who had assisted during a disaster were included in this review. Due to the transient nature of military nurses and nurses deployed to rural and remote areas, the specialty of midwives to care specifically for labouring women and their children and the unqualified status of student nurses, these subtypes were excluded from the review. Articles describing the experiences of a nurse in a rural or remote area, either first- or second-hand, were considered for inclusion. All articles were required to focus on the response phase of disasters. This was defined as ‘Actions taken directly before, during or immediately after a disaster in order to save lives, reduce health impacts, ensure public safety and meet the basic subsistence needs of the people affected’27. All methodological approaches were considered for inclusion in this review. Articles published in English during the years 2001–2021 were considered for review.

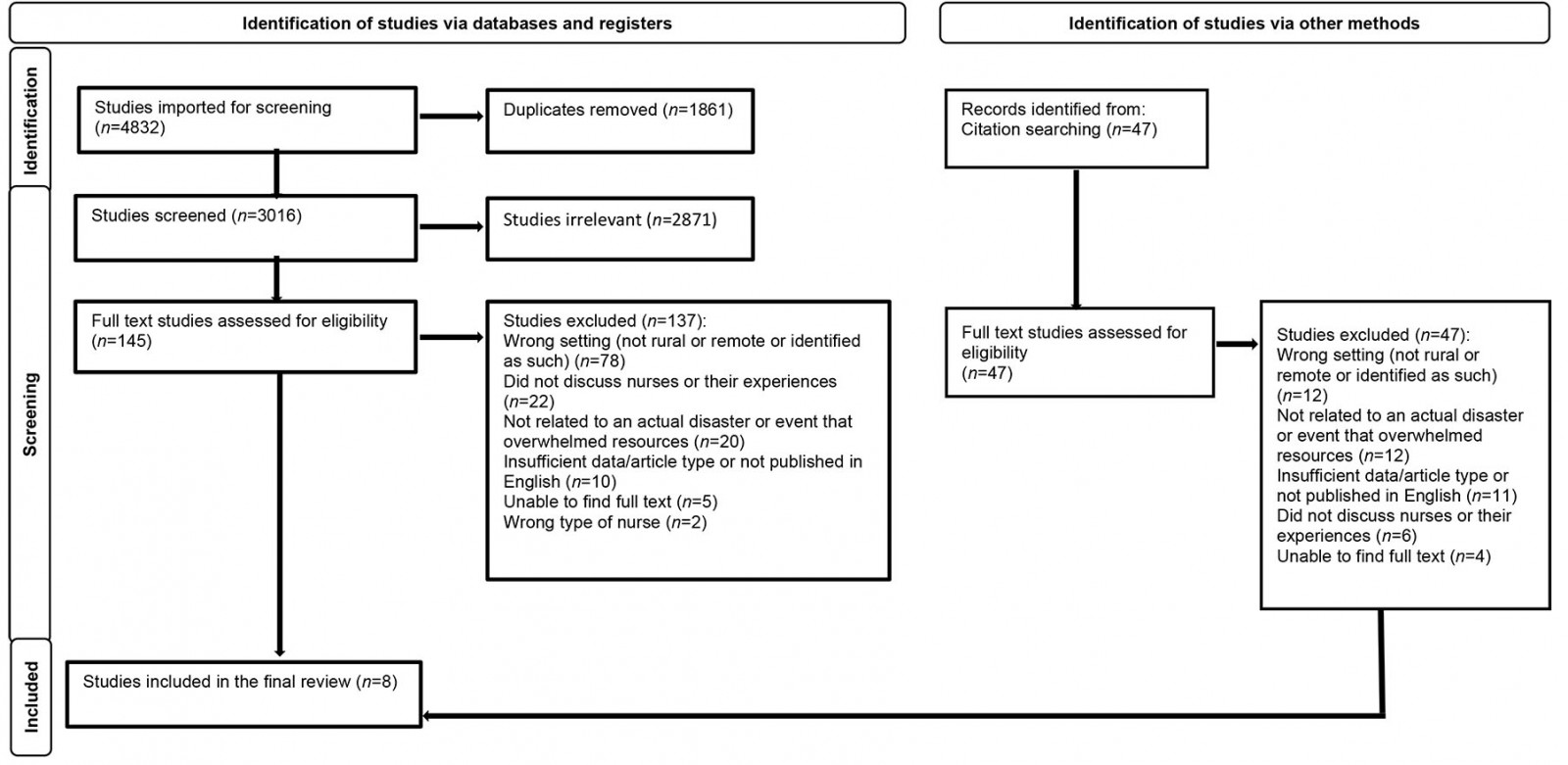

All identified papers were exported into Covidence Systematic Review Software 2021 (Veritas Health Innovation; http://www.covidence.org/home) and duplicates were automatically removed. Two independent reviewers examined the titles and abstracts to identify articles that met the inclusion criteria. The eligible full-text articles were retrieved and reviewed. Of the full-text articles that were considered appropriate, the reference lists of these articles were examined for any additional articles for inclusion. Any disagreements throughout this process were resolved through a third reviewer. The processes of the search and extraction are presented in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Fig1).

Table 2: Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram of study selection process.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram of study selection process.

Charting data

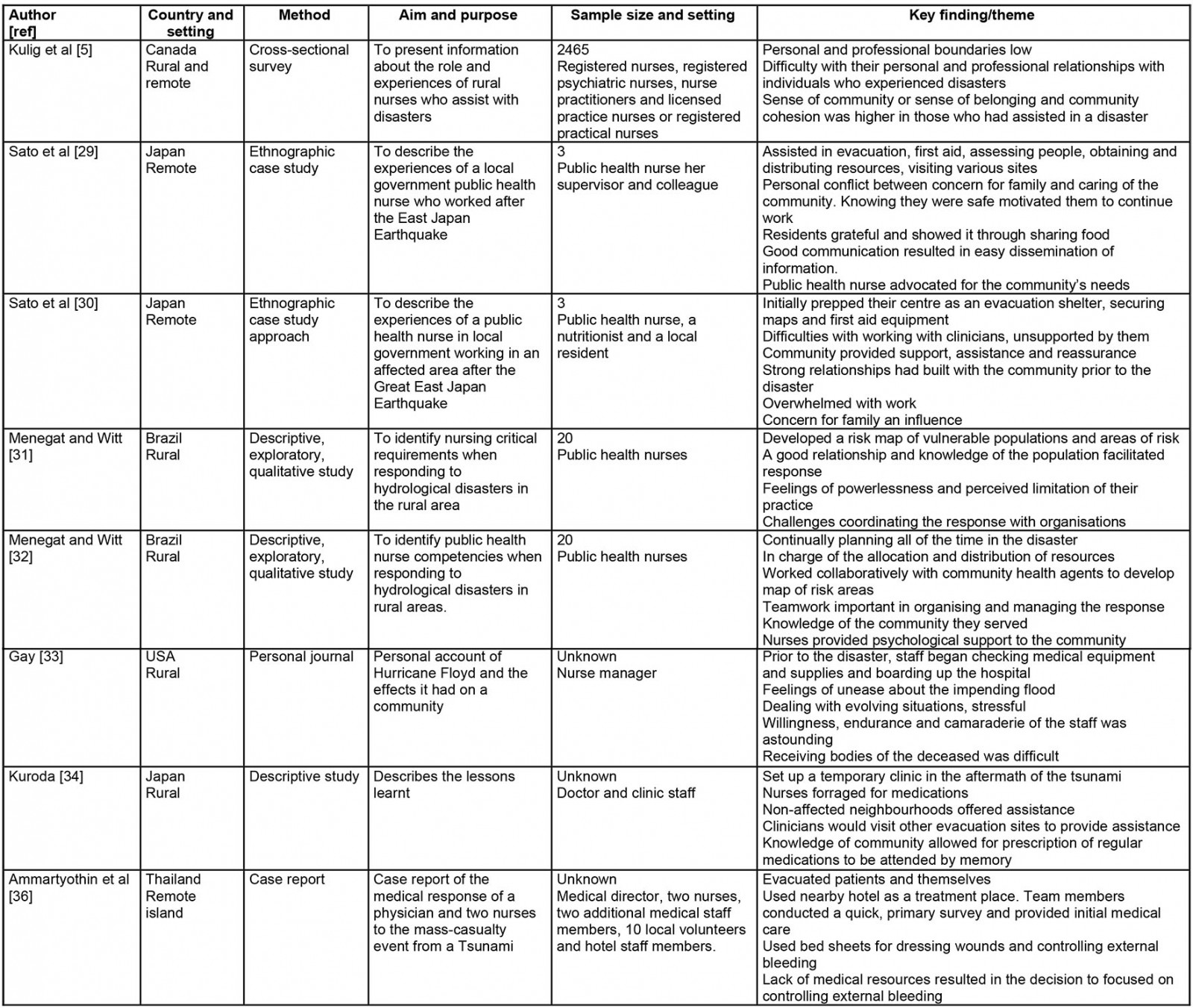

Data from articles included for review were extracted into a table (Table 3), which was developed by the review team. This enabled a logical and descriptive summary of the results, which aligned with the aims of this review.

Table 3: Data extraction framework

Collating, summarising and reporting results

Descriptive and thematic analyses of the findings were developed, as recommended by Arksey and O’Malley24. Basic numerical analysis, such as nature and frequency of the included studies, was undertaken. Key themes and conceptual categories were developed during the data extraction process, guided by Braun and Clarke’s six-step framework for thematic analysis28. The steps required basic coding of data, collating codes into potential themes/categories, checking codes to identify relationships or similarities and refining to create clear names for each28.

Results

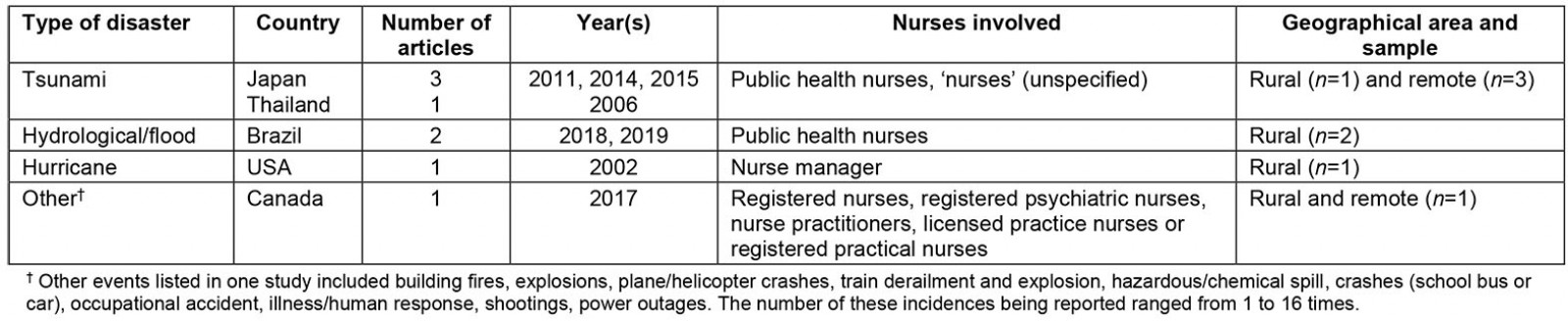

Eight articles met the inclusion criteria of this review; Table 4 provides a summary of each one. In terms of the disasters included in this review, they originated from Japan (n=3), Brazil (n=2), Canada (n=1), United States (n=1) and Thailand (n=1). Most articles were qualitative (n=7) in nature, and one (n=1) used quantitative methodology, with open-ended responses. Most of the articles were written with a focus on public health nurses (PHNs) (n=4). Two articles were written from the perspective of medical officers, with discussion on how the team (including nurses) responded to disasters. One was a first-hand account of a nurse manager’s experience assisting with a hospital’s disaster response. Tsunamis (n=4) were the most reported disaster in this review, with four separate accounts of two different tsunami events.

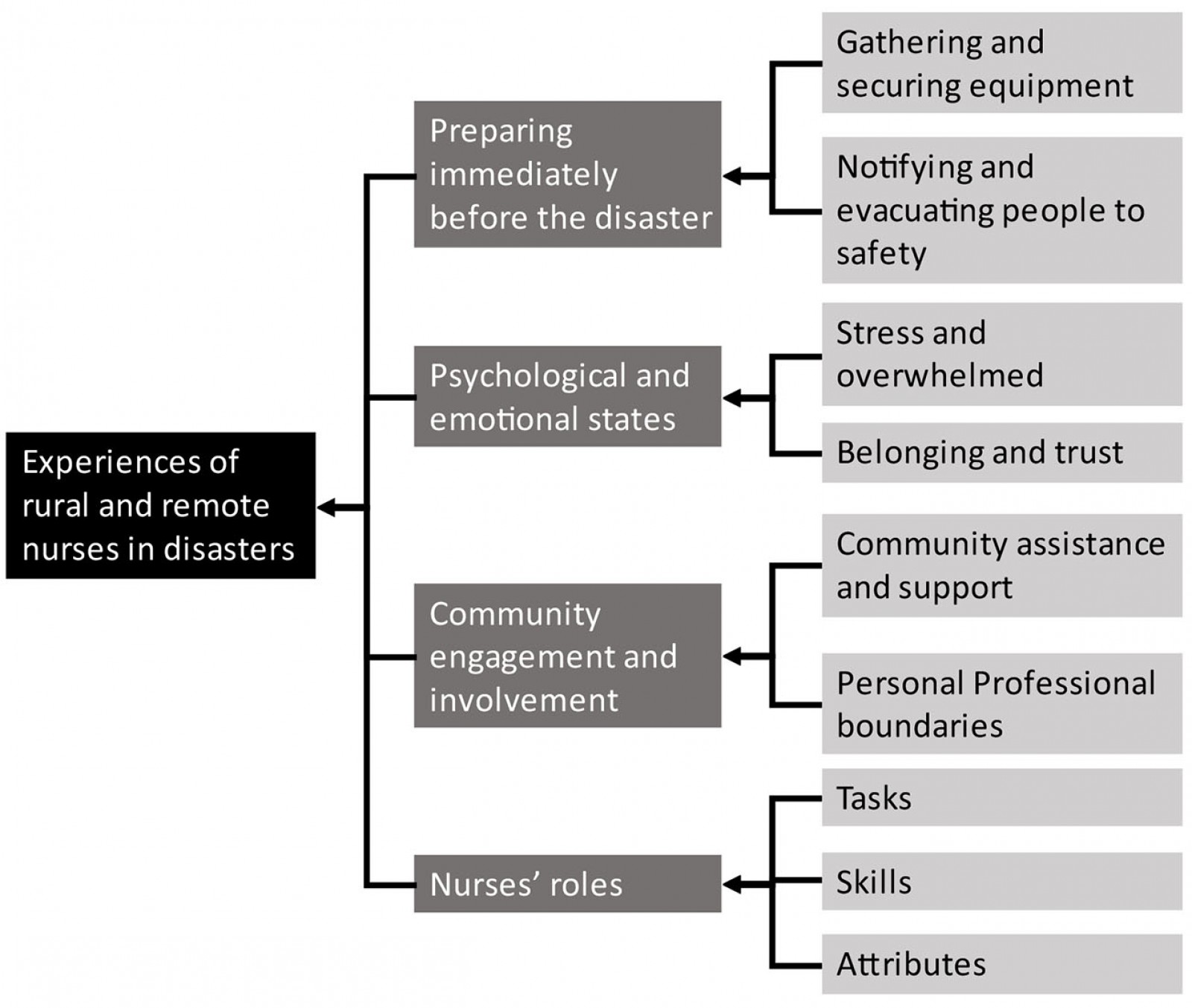

The results of the themes and categories found in the literature are presented in the following sections. Figure 2 is a concept map of the themes.

Table 4: Summary of disaster literature relating to rural and remote nurses experiences in disaster response.

Figure 2: Concept map of study themes.

Figure 2: Concept map of study themes.

Preparing immediately before a disaster

In some disasters, there are warnings of the event. In these crucial minutes directly before the disaster, healthcare professionals can perform critical actions that assist them in saving lives. Identified within this current review, nurses secured first aid equipment, disaster maps, notified others of the incoming threat and pre-emptively evacuated people to safer areas (n=4)29-32.

Two articles identified that these critical moments require nurses to be continually planning and reassessing. An account from a PHN noted that after an earthquake they had anticipated that a tsunami would be likely; therefore, the nurse was able to evacuate residents onto the roof of the facility that they worked in, ultimately saving their lives29. PHNs in Brazil reported that they had tried to plan for disaster response; however, when they arrived at the scene, they were faced with situations that their plan did not account for: ‘we had to be planning our actions all of the time’32.

Psychological and emotional states

‘Personal stress’, ‘feelings of unease’ and ‘powerlessness’ were expressed by rural nurses during disasters (n=2). Situations such as not being able to leave the hospital due to workload demands (n=1) and perceived limitations in their practice in relation to provision of essential goods (n=1) were reported in the literature32,33. Interestingly, one article mentioned the ‘distrust’ that a nurse felt towards the volunteers who assisted, noting that they did not show sufficient respect or consideration to the local people29. Nurses’ hardship on seeing the deceased, sometimes their own deceased colleagues, was noted in four articles5,29,30,33.

Other emotions and feelings of a more positive nature were expressed among rural and remote nurses. A sense of belonging and cohesion within their workplace or community was reported (n=3)5,29,30. This included a PHN who felt reassured by community members in her decision to establish an emergency operations centre and to assume the role of ‘stand-in’ director-general (n=1). ‘Trust’ and ‘generosity’ were reported by another nurse, after being provided with warm welcomes and meals upon arrival at the evacuation centres (n=1).

Community involvement, support and relationships

Disasters affected both community spaces and the communities themselves. Despite adversities, the support that the communities showed towards nurses and others was apparent in the literature. Unaffected neighbourhood groups provided food and water for those who were affected by the disaster (n=1)34. Support, cooperation and assistance from locals resulted in a nurse being able to manage the necessary activities at an emergency operations centre30.

Community relationships were noted as being important during disaster events. Nurses were required to develop relationships and rapport to establish both interpersonal trust and trust in their professional capabilities. The building of close relationships by nurses with their communities prior to a disaster and having knowledge of the community in which they served was discussed in most of the articles (n=5)29-32,34. The articles discussed how these relationships, and the consequent community knowledge that was developed, allowed for easier healthcare assessment and management, as well as the ability to advocate on the community’s behalf. The support from locals resulted in positive outcomes such as sharing of resources, advocating for change (after the disaster) and establishment of an essential disaster management centre.

Having both personal and professional relationships in a community can also create challenges for nurses. Personal and professional boundaries were identified as the ability to separate the nursing role from other roles or personal privacy respected in the community. One study noted that rural and remote nurses reported difficulty with having both personal and professional relationships with individuals who were affected by the disaster5. The professional–personal boundaries were reported as low among respondents who had assisted in a disaster in the previous 5 years. The rural and remote nature of their practice placed nurses in a challenging position, with an internal conflict between personal and professional obligations. This challenge was mirrored in other accounts (n=3), with some nurses feeling as though they were being torn between concerns about their own family and their obligation to care for the community29,30,33.

Disaster roles

Nurses performed many tasks during disaster events, which could be defined as time-bound work activities, duties or acts35. These included procurement, allocation and distribution of essential resources (n=4); assessment, triage and consultation with survivors (n=4); providing first aid and treatment (eg controlling haemorrhage, delivering a baby) (n=3); providing psychological support (n=3); and foraging for food and medications in the rubble (n=2).

Nurses’ skills demonstrated during disasters included networking and collaborating with other health agencies, as well as with survivors and residents, to assist coordination and response efforts (n=4). Being able to form these relationships resulted in the dissemination of information, support to provide care in difficult situations, and identifying those who needed medical assistance via mapping of risk areas29-32. One account highlighted the novel use of available resources, describing how staff used bed sheets within the hotel to which they had relocated to control bleeding in survivors36.

Although many functions in a nurse’s role have been taught, learnt or achieved through competencies, personal attributes are, by definition, unique to each nurse. Nurses’ commitment and dedication to continue to provide care to the community in which they served was highlighted (n=4)29,30,32,34, often despite personal hardship (n=3)29,30,33. These attributes resulted in prompt triage, emergency prescriptions, initiation of preventative measures, advocacy for establishment of emergency operations centres, and stepping up to assist with the delivery of a baby30,34.

Discussion

Disaster roles

Being at the forefront of health care, nurses are often called upon to respond to disasters37-39. This review indicates that nurses play an important role in disaster response and, at times, are sole providers of care in the immediate aftermath of a disaster29. This review indicates that rural and remote nurses were required to provide substantial care to individuals and communities by evacuating, performing health assessments, triaging, giving basic first aid, providing primary healthcare services such as immunisations, supporting health education such as sanitation and risk communication as well as monitoring disease outbreaks37,40.

Within the wider disaster nursing literature, many articles outline the experiences and roles of nurses in disaster situations; however, the focus settings and populations are urban and metropolitan10,13,38,41,42. Some may argue that the roles of clinicians should be somewhat transferable from one setting to another; however, this review suggests that rural and remote nurses are required to perform a more ‘generalist’ role. This requires the nurses to be knowledgeable and proficient across all domains of health care, as they are at times the only clinician at a clinic or have minimal support from ancillary staff6,43. The wide scope of the role of rural and remote nurses requires a vast knowledge and skills base to support it6,43. Consequently, the nexus between clinician, context and role need to be better understood, to provide richer insights into the true extent of these skills and their development. This may shed light on the true differences between rural and remote nurses and their abilities to respond to disasters when compared to their urban and metropolitan counterparts.

Disaster response

Previous disaster-related rural and remote research studies have investigated registered nurses, advanced practice nurses, licensed nurse practitioners, nurse managers and public health nurses17,44. These articles focused on perceived disaster preparedness, confirming that nurses of all levels and backgrounds worked in the rural and remote setting. However, in relation to disaster response, the existing literature was essentially silent in relation to nurses and their roles. Further research is therefore necessary to identify what these different types of nurses do and their experience in disaster contexts. Such research could identify gaps between preparedness and capability in response, as this may differ depending on location or qualification level. Longer term, this could allow identification of skills, attributes and knowledge required of nurses working in these areas, thereby informing the education and recruitment of skilled clinicians in the future.

Public health nurses in disasters

Interestingly in this review, several articles focused on PHNs in rural and remote areas. Worldwide there is considerable variability on the scope, role and designation of PHNs45, resulting in confusion about their expected involvement and roles in disaster response. For example, the terms ‘community nurse’ and ‘public health nurse’ have been used interchangeably within the literature45,46. Both of these positions have a different focus, one with direct care and the other providing services at the population level of health46. Nevertheless, half of the articles included in the present review highlighted the involvement of PHNs in disaster response, raising the potential for further research into what different ‘types’ of nurses do and their experience in disasters.

Psychological and emotional states

The emotions and feelings that are experienced and expressed by nurses in times of disaster can give insight into how they affect clinical performance and the ability or willingness of nurses to work under such circumstances. The willingness of clinical staff to report for work during a disaster has been explored many times in the literature. Factors such as the nature of the disaster itself, family obligations and commitments, workplace norms and peer pressure have all previously been explored; the studies are predominantly urban nurse-focused20,21,47-50.

It appears in this current review that rural and remote nurses’ commitment to care for their community has implications for their willingness to respond in disaster situations, and may be a motivational influence on their wider decision-making. Interestingly, nurses’ commitment to care for the community has not been a significant focus of the reviewed literature; this would suggest that commitment to care for the community is a legitimate area for further research regarding nurses in rural and remote areas.

The difficult and challenging emotions that come with stressful events like disasters was confirmed in this review. Fear of the unknown, of what they could see and be exposed to, fear for family safety, safety of self and the associated stress has been commonly reported20,51,52. Interestingly, the significant long-term emotional and psychological impacts that disasters could have on both survivors and clinicians were highlighted in this review5,29,30. In a Delphi study of disaster nurses, the need for research to focus on the psychological and mental health and wellbeing of both nurses and the community was highly ranked53.

Professional boundaries and community relationships

In this review, rural and remote nurses self-reported blurred boundaries between their professional roles and personal lives5. Historically, this blurring of boundaries has brought benefits (eg trust) and drawbacks (eg lack of privacy) for nurses54,55, generally being reported as difficulties in separating personal and professional lives. Consequently, demarcation between these roles has been found to be difficult, particularly where a nurse lives and works in the same area54. Issues such as confidentiality or needing respite from work responsibilities could arise55. Conversely development of trust, warmer relationships and friendships were also noted to occur, which positively affected nurses’ engagement with patients and their overall care54,55.

In this review, fluid professional boundaries appeared to result in nurses’ increased willingness to respond or the incidence of responding to a disaster5, together with their increased willingness and commitment to care for the community despite personal hardship29,30,33. Their familiarity with individuals’ medical history enabled nurses to accurately issue emergency prescriptions without access to medical records34.

The reviewed literature also found that rural and remote nurses’ relationships and sense of community were strong. Nurses working in this context had personal knowledge or relationships with many of the people for whom they provided care. Their local mechanic, butcher or neighbour could be potential survivors of a disaster. The small and intimate populations found in rural and remote areas led to distinctly close relationships between the community members and the nurses who work there.

Limitations

Overall, there is a lack of literature exploring the experiences of rural and remote nurses during disasters. The included articles were largely based in Japan or were related to public health nursing. As a result, the findings are not necessarily transferable across different countries or for nurses working in other roles. Similarly, there was a lack of literature published in an Australian context, highlighting the gaps within the rural and remote settings in disaster response. Further, the lack of literature makes it difficult to draw conclusions from the findings of this review. The decision to include articles that stated ‘rural’ or ‘remote’ may have included data that were not directly comparable due to the lack of internationally accepted definitions of what constitutes rural and remote areas. This may have resulted in some papers being identified as rural or remote, which would be have been classified as urban in another jurisdiction. While critical appraisal in scoping reviews is not preferred, it could be seen as a limitation within this current review.

Conclusion

This literature review provided some insight into the existing literature on the experiences of rural and remote nurses in disasters. The review suggests that nurses who work in rural and remote areas play a significant role in disaster response. There appears to be a nexus between clinicians, their role and the setting in which they find themselves, paving the way for further studies to be conducted within rural and remote settings during disasters. Within this review, superficial identification of roles, psychological and emotional factors, and community influence were proposed.

Subject to the previously stated limitations, the existing literature does not detail the extent to which rural and remote nurses are involved in disasters, how their roles change in disaster situations and how their professional scope is consequently altered. In an Australian context, there is currently no literature that explores this. As noted earlier, nurses in rural and remote locations are subject to heightened blurring of personal–professional boundaries, resulting in a loss of ability to separate self from community; this has not yet been investigated in detail in disaster situations. Furthermore, the extent to which rural and remote nurses’ involvement in disaster response is influenced by community relationships and personal/professional boundaries, and how this may contrast with those in other geographical settings, is unclear. These matters remain grounds for significant future research.

References

You might also be interested in:

2011 - Farewell Ralph McLean - a quiet contributor to rural health