Context

The Kimberley region, located in the northern part of Western Australia, is remote and sparsely populated, with an estimated 34 364 residents across a 423 000 km2 area1. The prevalence of dental disease is significantly higher in the Kimberley compared with other regional centres, and providing adequate access to timely dental care to remote Aboriginal communities in the region remains a challenge and is both a state and national priority2-4. However, the low population densities combined with the high running costs of a fixed dental practice mean that establishing a permanent dental workforce and full-time services is generally not viable no sustainable. As a result, volunteer-led services have been employed to ‘fill the gaps’ and extend dental care to Kimberley communities in a similar capacity to other isolated and underserved communities globally5,6.

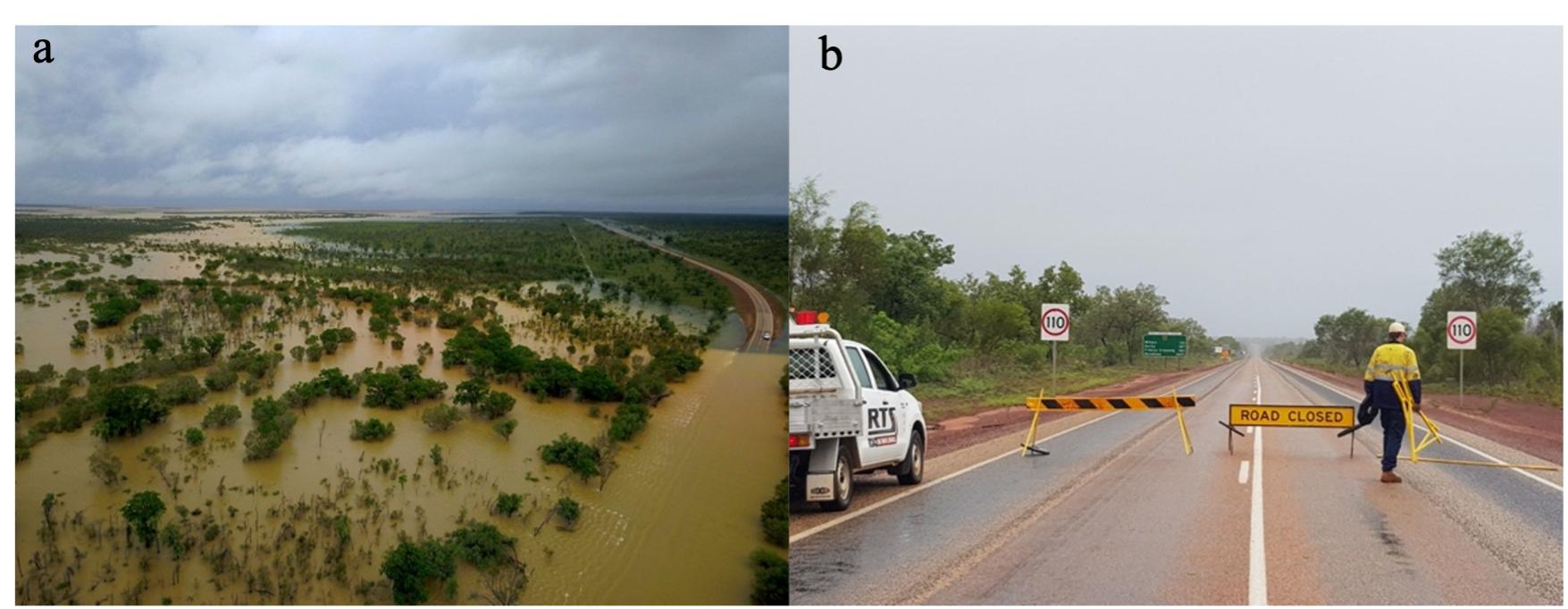

The vast landscape and extreme climate of the Kimberley also impacts on accessibility to care. The region experiences a tropical monsoonal climate with approximately 90% of the annual rainfall occurring over a span of 3 months7. This presents significant challenges in access to care and the provision of services, as torrential flooding often results in closure of major highways and arterial roads, restricting transport to and from remote communities for extended periods (Fig1). This report details the development and design of the Kimberley Dental Team (KDT) model since its inception in 2009.

Figure 1: Left: Aerial photograph showing torrential flooding cutting off the Kimberley’s major highway. Right: Sporadic road closures enforced due to the extent of flooding.

Figure 1: Left: Aerial photograph showing torrential flooding cutting off the Kimberley’s major highway. Right: Sporadic road closures enforced due to the extent of flooding.

Issue

Aboriginal children experience higher rates of dental disease and hospitalisation than the general population, with poorer outcomes reported in children living in rural and remote communities8. Australia’s National Oral Health Plans, 2004–2013 and 2015–2024, have identified Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as a priority population requiring targeted resources and support2,3. In the context of KDT, teachers and community members in Halls Creek, a remote community in the East Kimberley, identified that many children were experiencing dental decay and toothache and that a regular dental service was unavailable9. During a visit to Halls Creek in 2009, as part of the Madjitil Moorna choir: Singers of Aboriginal Songs, Jan Owen AM and John Owen AM were opportunistically invited to provide basic dental screening and dental health education to the local school children. The initial screening found approximately 70% of children presented with acute dental infection and severe early childhood caries10.

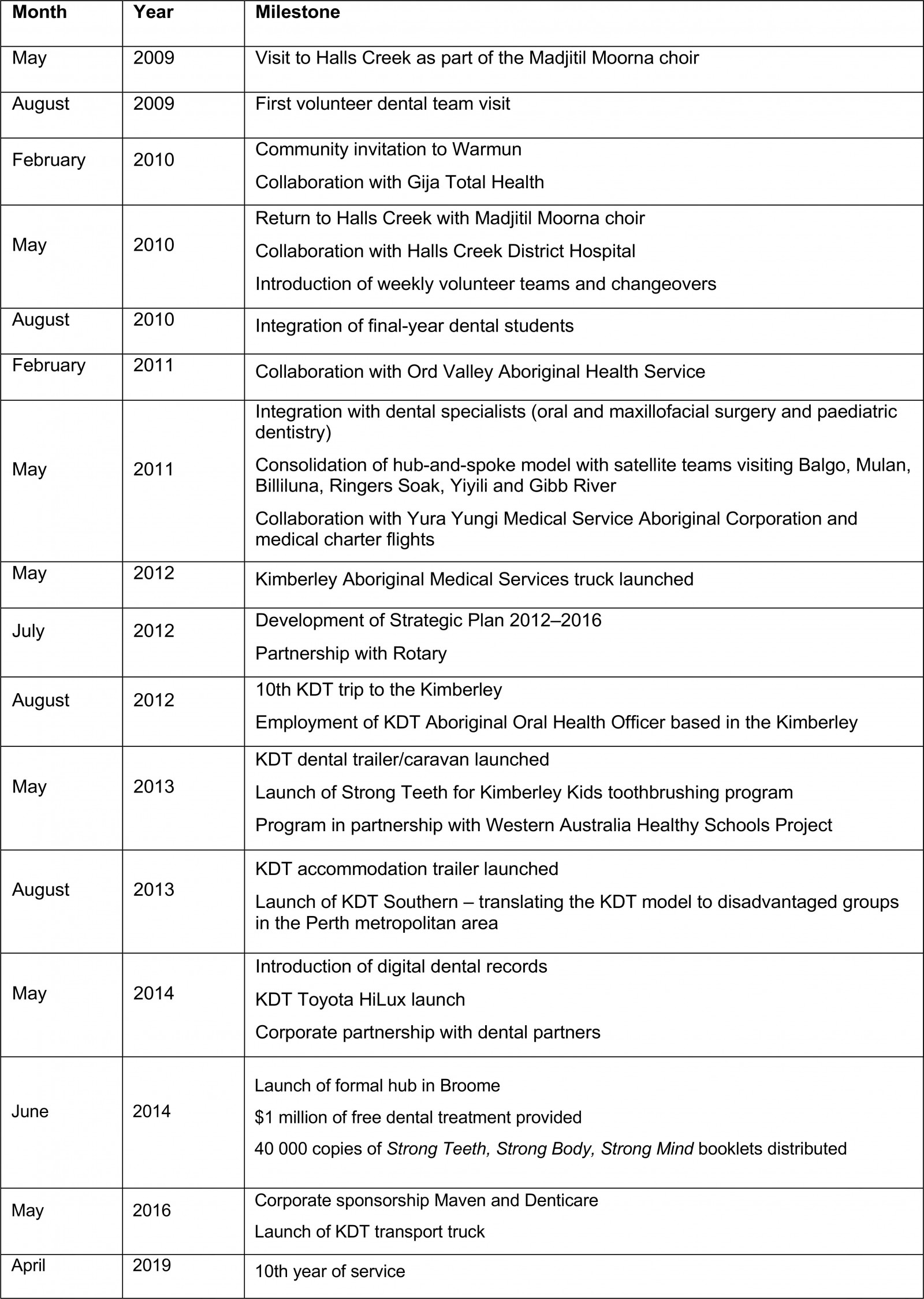

This visit sparked an ongoing collaboration with the school and local community, laying down the foundation of the KDT model. Volunteering with KDT is now an annual event where rotating teams of volunteers typically spend a week each in the Kimberley over a period of up to 3 months to provide dental health education and treatment following community invitation. The KDT is thus a non-for-profit, non-government, volunteer organisation that has been operating since 2009. The history and key milestones of KDT are further summarised in Table 1. This article aims to describe the KDT model of care, including its development, resources, operational factors and organisational characteristics.

Table 1: Development of the Kimberley Dental Team (KDT), and key milestones

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for this study was received from the Western Australian Aboriginal Health Ethics Committee (ref. 1023).

Lessons learned

The KDT model has evolved over a decade to now consist of the following structural components: oral health promotion initiatives, dental service delivery including mobile dental units, volunteer recruitment, and integration with education and organisational governance.

Oral health promotion

Strong Teeth for Kimberley Kids toothbrushing program: In remote Kimberley communities a tube of fluoridated toothpaste typically costs $7 and a toothbrush can cost up to $10. This poses a significant financial barrier to dental care and oral hygiene for many families. Without access to such basic necessities, the prevention of dental caries and periodontal disease in remote communities is near impossible. As a response, the daily school-based Strong Teeth for Kimberley Kids toothbrushing program was developed. The program is funded by KDT but driven by communities and ensures that each child receives an oral hygiene pack with a toothbrush and toothpaste at the beginning of each school term. Over 20 000 oral hygiene packs and education material are distributed to 43 schools, health clinics, nursing posts and Indigenous corporations across the Kimberley region each year. KDT’s motto, ‘Strong Teeth, Strong Body, Strong Mind’, underlines the importance of oral health and its connection with general health and wellbeing.

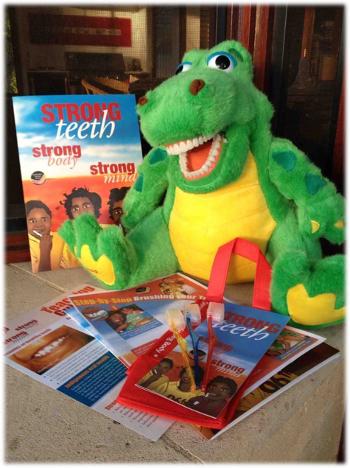

To complement the toothbrushing program, a teaching guide and culturally appropriate educational booklet were developed with input from the East Kimberley communities (Fig2). The logistics of the overall program led to the development of an oral health promotion officer role in collaboration with the WA Healthy Schools program11. The officer is able to engage with teachers and nurses locally to both support and evaluate the conduct of the program in the absence of KDT visits to the region. Through discussion with school teachers a recyclable canvas bag, rather than plastic ziplock bags, was designed to store toothbrushes and toothpaste. This allowed children to personalise and add a sense of value to their oral hygiene kit, hang the bags in class and take them home at the end of a semester (Fig3).

Figure 2: Strong Teeth, Strong Body, Strong Mind teaching guide, educational booklet and mascot Craig the Croc.

Figure 2: Strong Teeth, Strong Body, Strong Mind teaching guide, educational booklet and mascot Craig the Croc.

Figure 3: Left: Children involved in the Strong Teeth for Kimberley Kids toothbrushing program. Right: Kimberley Dental Team recyclable bags used by each child to store their toothbrush and toothpaste while at school.

Figure 3: Left: Children involved in the Strong Teeth for Kimberley Kids toothbrushing program. Right: Kimberley Dental Team recyclable bags used by each child to store their toothbrush and toothpaste while at school.

School-based screening: The supervised toothbrushing program is complemented by annual dental check-ups by KDT, which visits communities by invitation. Each community is aware of the visits ahead of time and thus the school is able to distribute consent forms and liaise with parents beforehand. During a typical KDT trip, a team of volunteers will visit school classrooms, conducting an examination (with charting), a plaque index, orthodontic classification and triaging each child based on caries risk and treatment needs. The use of Craig the Croc as a mascot encourages participation and enthusiasm among the children and helps mitigate any immediate feelings of dental anxiety, particularly among younger children (Fig2).

Personnel

Volunteers: As a volunteer-based, non-profit organisation all personnel involved with KDT essentially provide their expertise and time pro bono. Typically, volunteers from around Australia spend a week per year in the Kimberley (repeat volunteers may spend additional weeks). As a result, a new team of volunteers change over on a weekly basis for the duration of KDT’s clinical program (approximately 3 months annually during the dry season of May to September). The founding directors of the program, Jan and John Owen, maintain a stable presence – providing guidance and leadership for the teams throughout the period.

Volunteer recruitment has been identified as one of the most pressing challenges faced by healthcare administrators12. Volunteer recruitment for KDT initially began through internal networks and word of mouth, and attracted dentists and dental nurses keen to provide their services13. The characteristics of KDT volunteers have been described previously13, and a notable strength of the program has been the high number of repeat volunteers. A number of enablers, including the following, may be attributed to this:

- Volunteers only need to commit a relatively short amount of time (1 week) away from their families and work.

- Transport and accommodation costs are largely supported by the KDT, mitigating a financial burden on volunteers.

- A sense of family is fostered and bonding experiences are created within communities in the Kimberley, as well as the KDT network.

- The value of volunteer efforts is highlighted and recognised through regular newsletters and annual social gatherings.

- There is an opportunity to travel and explore the Kimberley region.

- New generations of volunteers are attracted through scholarships provided to final-year dental students and new graduates.

Education–service integration: Recruitment and retention of dental practitioners into rural and remote communities in Australia is a well-recognised challenge14. The literature highlights two recurring themes: students from a rural background are more likely to return to rural practice, and the more exposure students have to rural practice the more likely they are to practise in a rural area at some stage in their careers15,16. In order to build capacity, KDT partnered with the University of Western Australia to create supervised outreach placements for final-year dental students who are selected based on merit, and interest in remote and Indigenous oral health. This integration of education and service allows students to gain valuable exposure to oral health in the Kimberley while being supported by an experienced team of clinicians and volunteers. As reported by a recent graduate17:

I feel it is a shame that all students don’t have the opportunity to experience the trip that I had … We do some small units on Aboriginal Indigenous, Rural and Remote Oral Health at university, however the experience of actually participating in the delivery of such an effective care model is far more valuable than sitting in a lecture hearing about statistics ever will be. The standard of care set by the team was inspirational and has motivated me to actively continue to further my knowledge and understanding.

Outreach placements have demonstrated benefits to students’ confidence, competence, appreciation of working in a team environment, understanding existing barriers to care and raising cultural awareness and professionalism through an increase in the quantity and variety of clinical experience18.

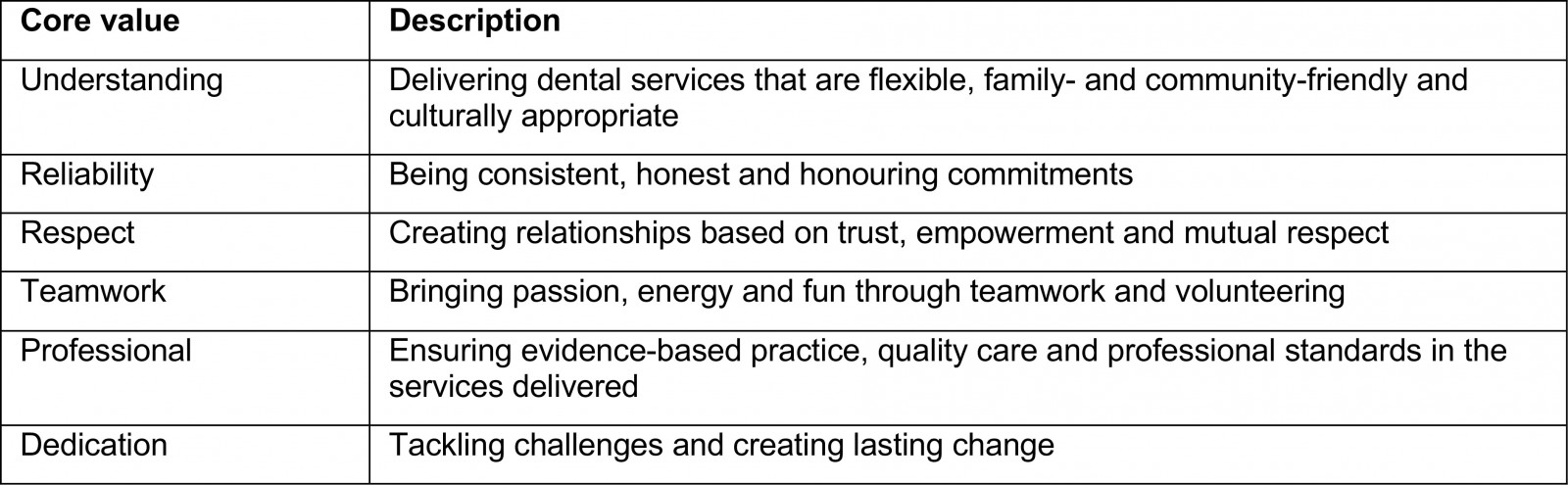

Governance: Organisational governance and evaluation are central elements to the sustainability and growth of volunteer organisations but they are traditionally given a lesser priority than clinical care19. Consultation with key stakeholders led to the development of a strategic plan in 2012 and identification of core values deemed to be central to the KDT model (Table 2)20. A steering committee was also established, comprising members of the Kimberley community, KDT volunteers and representatives from partner organisations such as Rotary, which provided additional leadership and strategic guidance. KDT’s overarching governance includes a board of directors, which was established to consider (1) access to government grants and corporate sponsorships; (2) increasing Aboriginal input and strategies around community liaison; (3) occupational health and safety policies and procedures; (4) taxation, financial planning and accounting; (5) marketing, branding and communication; and (6) development of IT systems including management of administrative and patient records.

Table 2: Kimberley Dental Team core values

Approaches to service delivery

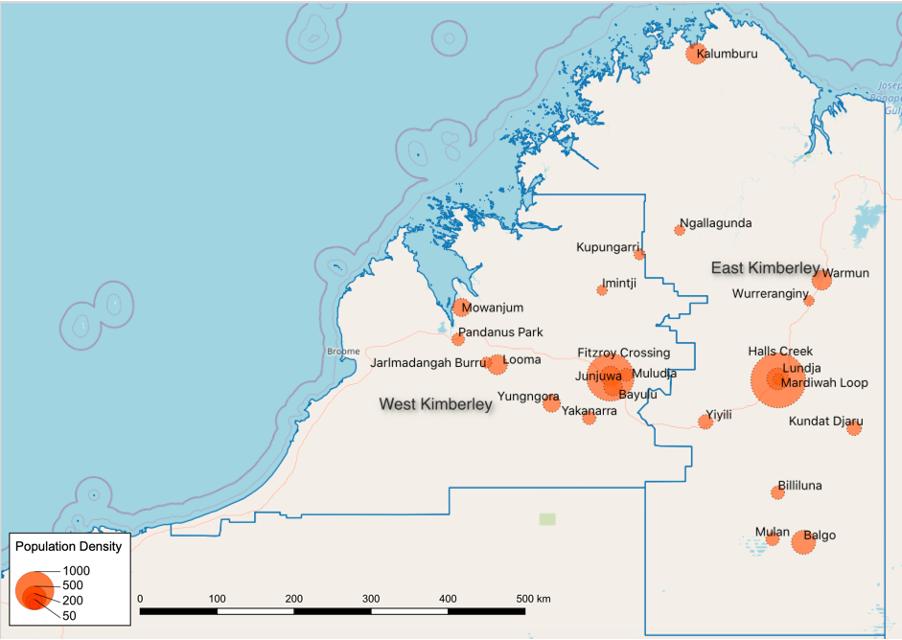

Hub-and-spoke model: The KDT program was started in the remote Kimberley town of Halls Creek, which is part of the larger Halls Creek district (which covers an area of over 143 000 km2). The Halls Creek township also includes a number of smaller communities, such as Red Hill and Mardiwah Loop communities (Fig4). An estimated 3000 people reside outside of the Halls Creek town site, in surrounding remote communities (Fig4).

In order to efficiently service both the town and outlying communities, a hub-and-spoke model was employed, resulting in an anchor establishment (hub) in Halls Creek, which offers a full array of services and acts as a home base for volunteers and stock. The hub is complemented by secondary establishments (spokes) from which satellite teams would make day/overnight trips to outlying communities, often with the use of mobile dental units21.

Figure 4: Map of the Kimberley region, showing communities serviced by Kimberley Dental Team and population density.

Figure 4: Map of the Kimberley region, showing communities serviced by Kimberley Dental Team and population density.

Integration with Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Services (ACCHSs): Integration with existing ACCHSs is critical in providing culturally secure care while maintaining the sustainability of the KDT model. As asserted by Dyson and colleagues22(p. 189):

Aboriginal health services present a non-threatening, culturally secure environment that Indigenous people are comfortable attending. This environment supports the maintenance of close service–community relationships and fosters cultural exchange and shared learning, all of which are crucial for the success of visiting remote services.

Many of the hurdles faced when delivering care to remote Aboriginal communities can be overcome by working with existing community-run services, which play an important role in providing community liaison, rapport and local knowledge. Furthermore, linking dental services to existing primary health services, in particular community ACCHSs, provides the opportunity for integrated multidisciplinary health care, thereby bringing oral health into the general health space. This not only promotes a collaborative health service but also enables a common-risk factor approach to disease prevention and management23.

Cooperative use of infrastructure: Currently, public services are operated by the state-run Dental Health Service and are available in larger towns in the Kimberley; however, the frequency of visits is highly variable, with the West Kimberley typically being better serviced than the more remote communities in the East Kimberley, thus facilitating KDT to ‘bridge the gap’24. In general, volunteer initiatives often fail to create lasting change when operating independently of local services5. As a free or low-cost service, volunteer models have the potential to develop a parallel system, which can devalue and undermine the regular health service5. As asserted by the Kimberley Aboriginal Health Planning Forum24:

While the activities of visiting providers … are praiseworthy, their future contribution should not and cannot be relied on as an alternative to funded government service provision.

Therefore, the KDT model relies on integration and partnership with existing services including ACCHS, the Dental Health Service and private practitioners. This collaboration occurs through a variety of pathways such as regular communication to avoid duplication of efforts, shared use of infrastructure to maximise efficiency, and facilitating triage and onward referrals to ensure continuity of care.

Mobile dental units: The use of mobile dental units is central to the KDT model of care. This approach extends the reach of the service, allowing several smaller and more remote communities to access care without the need and associated costs of fixed clinics. Furthermore, as transport to dental services is a prime barrier to care, the use of mobile units is welcomed in bringing services to the heart of the community25. By doing so the awareness and publicity of the service are also heightened and practitioners are better able to engage with the community rather than being confined within the walls of a fixed dental clinic25. Over the years, several different types of mobile dental units have been designed and used by the KDT in response to the community’s needs. This includes a ‘fly-in fly out model’, a purpose-built, dual-cab mobile dental truck with accommodation capacity, mobile dental caravan and transport vehicles (Fig5). However, the sophistication and technical intricacies of different mobile vehicles pose several challenges including the need for specific driving licences and driver training, knowledge of electrical and hydraulic systems, storage of vehicles when not in use, and associated insurance and maintenance costs.

Figure 5: Mobile dental vehicles: (a) Kimberley Aboriginal Medical Services/Kimberley Dental Team (KDT) truck and McCusker Charitable Foundation/KDT dental caravan. (b) Modified Toyota HiLux dual-cab truck. (c) KDT transport truck. (d) A helicopter visit to remote schools.

Figure 5: Mobile dental vehicles: (a) Kimberley Aboriginal Medical Services/Kimberley Dental Team (KDT) truck and McCusker Charitable Foundation/KDT dental caravan. (b) Modified Toyota HiLux dual-cab truck. (c) KDT transport truck. (d) A helicopter visit to remote schools.

Accommodation: Accommodation of large volunteer teams in community is a significant logistical challenge that is often overlooked. In some instances, short-term nursing housing is rented, while in other instances camping equipment is used to facilitate short-term lodging. These extraneous factors and equipment add several dimensions to the service delivery model, which extends beyond simply providing clinical care. However, the notion of living and working together in community plays a significant role in the degree of cultural immersion and team bonding, which are unique to volunteer-based models of care – leading to a sense of family and belonging13,26.

Evaluating outcomes

Evaluating dental outcomes in remote communities is critical but can be challenging, particularly for volunteer organisations. The difficulty of attaining adequate, regular follow-up records over an extended period and the need to account for confounding variables such as socioeconomic status, which influence health behaviour, exemplify these challenges. Despite this, the success of the model is supported by qualitative community feedback, which underlines the value of the KDT mobile dental units to remote communities and the importance of school-based oral health promotion25. This is also reflected by the uptake of the Strong Teeth for Kimberley Kids toothbrushing program across 43 schools in the region, which has been sustained since 20139. Moreover, when assessing emergency dental extractions, which act as a proxy measure of acute need, a 10-year audit of KDT service records has shown a 3% linear reduction in these procedures year on year from 2010. In the past 10 years, the model has thus developed from one primarily providing emergency surgical treatment to one providing primarily preventive and restorative treatment.

Conclusions

The provision of dental care to remote Aboriginal communities in the Kimberley is complex and involves careful consideration of the unique environmental, cultural, organisational and clinical factors at play. The KDT model has evolved over the course of a decade through a process of ongoing evaluation and community feedback, from initially catering to meet acute clinical needs to a more comprehensive governance and operational framework. This framework is centred on community engagement, collaborative care, integration with existing services and the use of a multifaceted hub-and-spoke model to provide oral health education and complement existing dental services to remote Aboriginal communities in the Kimberley.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the input of the external steering committee and reference group in reviewing the accuracy of the manuscript and providing details of the KDT program and program milestones.

Declaration of interest

Dr Jilen Patel is a member of the KDT Board. This is an unpaid and voluntary position. Any reporting bias has been mitigated through the use of external authors and investigators who do not have any involvement with KDT. Furthermore, a variety of data sources have been used to present the material in this study, which has been the subject of external review.