Introduction

A majority of European as well as other high-income countries aim to ensure health coverage for all citizens, by optimizing the availability and accessibility of health services in all geographical areas1,2. In many European countries, a key priority is to ensure at least sufficient primary care by general practitioners (GPs), as they are the first local contact point for health service and have a crucial role as gatekeepers for hospital care. This is most efficient for the regional equity in health outcomes as well as the cost-effectiveness of the healthcare system3,4. Yet underserved areas that experience lower levels of primary care and GPs capacity, also known as ‘medical deserts’, are still present in Europe.

In recent decades, there has been an increase in attention from policymakers and researchers on the recruitment and retention of (family) physicians to solve national and regional shortages. Previous research has focused on multiple contributing determinants of physician recruitment and retention in underserved areas5-7. Factors found positively associated with the preferences of physicians for rural job uptake are, among others, a rural background of medical students or a rural exposure during medical school5,6. Still, the majority of physicians are less willing to work in rural and remote areas. Reasons for this consist of several perceptions of physicians on these areas, such as professional or social isolation, the intensity of the workload, poorer job opportunities for spouses, or income level; all contribute to an overall perception that rural and remote areas are correlated with lower job satisfaction7.

To tackle these driving factors, various strategies have been proposed. For example, a comprehensive set of approaches has been developed by the WHO to guide countries in encouraging rural living and employment for health workers8. Overviewing the state of the art in research, the majority of studies on recruitment and retention of GPs have focused on rural areas in large countries such as the USA or Australia9,10. However, recent studies on interventions to recruit and retain GPs in underserved areas in smaller scale health systems, such as European countries, are scarce. Hence, an overview and evaluation of these studies is urgently needed – to uncover valuable lessons for European national policies to counteract future rural GP shortages as well as to ensure universal health coverage in the European region.

Objective and research questions

This study provides an overview of the research on GP recruitment and retention interventions in medically underserved areas within European countries. The goal of this study is to investigate and summarize qualitative and quantitative studies focusing on approaches and their effectiveness to improve GP recruitment and retention in underserved areas. Conducting a review of publications over the past 10 years, the aim is to provide insight into various strategies that have been recently initiated and studied in Europe. This extension of knowledge on recruitment and retainment, especially focused on GPs, can inform and support healthcare professionals, policymakers and decision-makers toward a more specific tailored strategy. Therefore, this review is structured by the following research questions:

- What are the most frequently used strategies for recruitment and retention of GPs in European medical deserts?

- To what extent are these interventions for recruitment or retention of GPs in medical deserts effective?

Methods

Search strategy

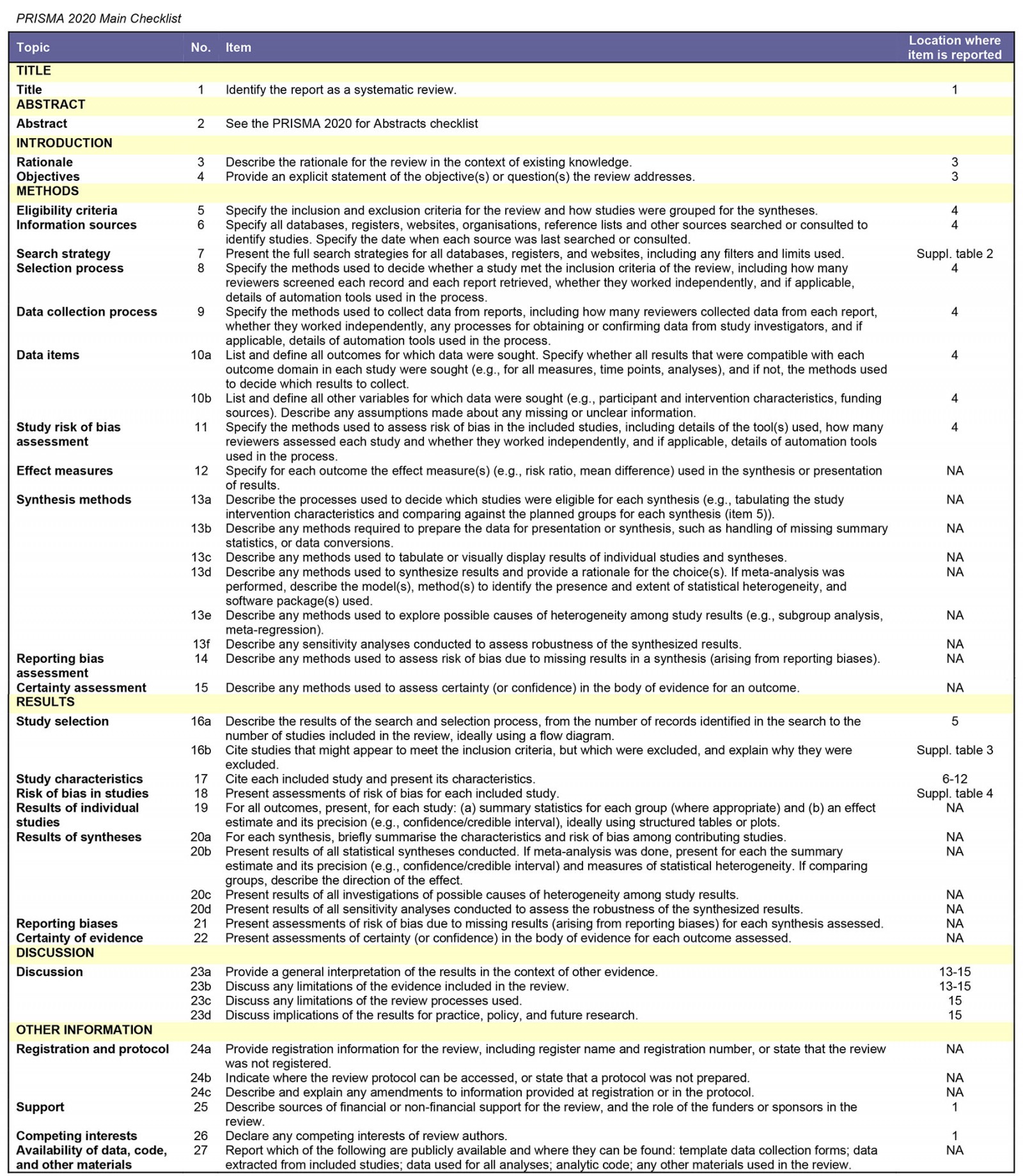

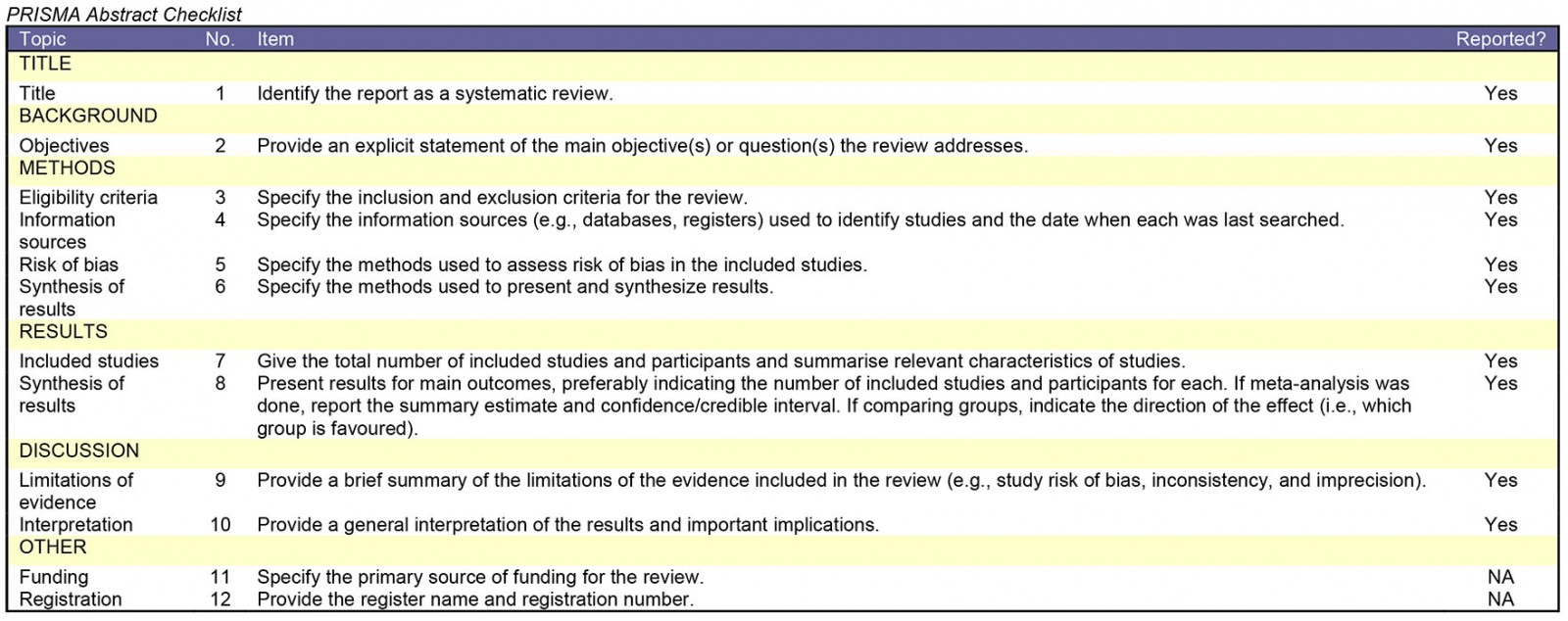

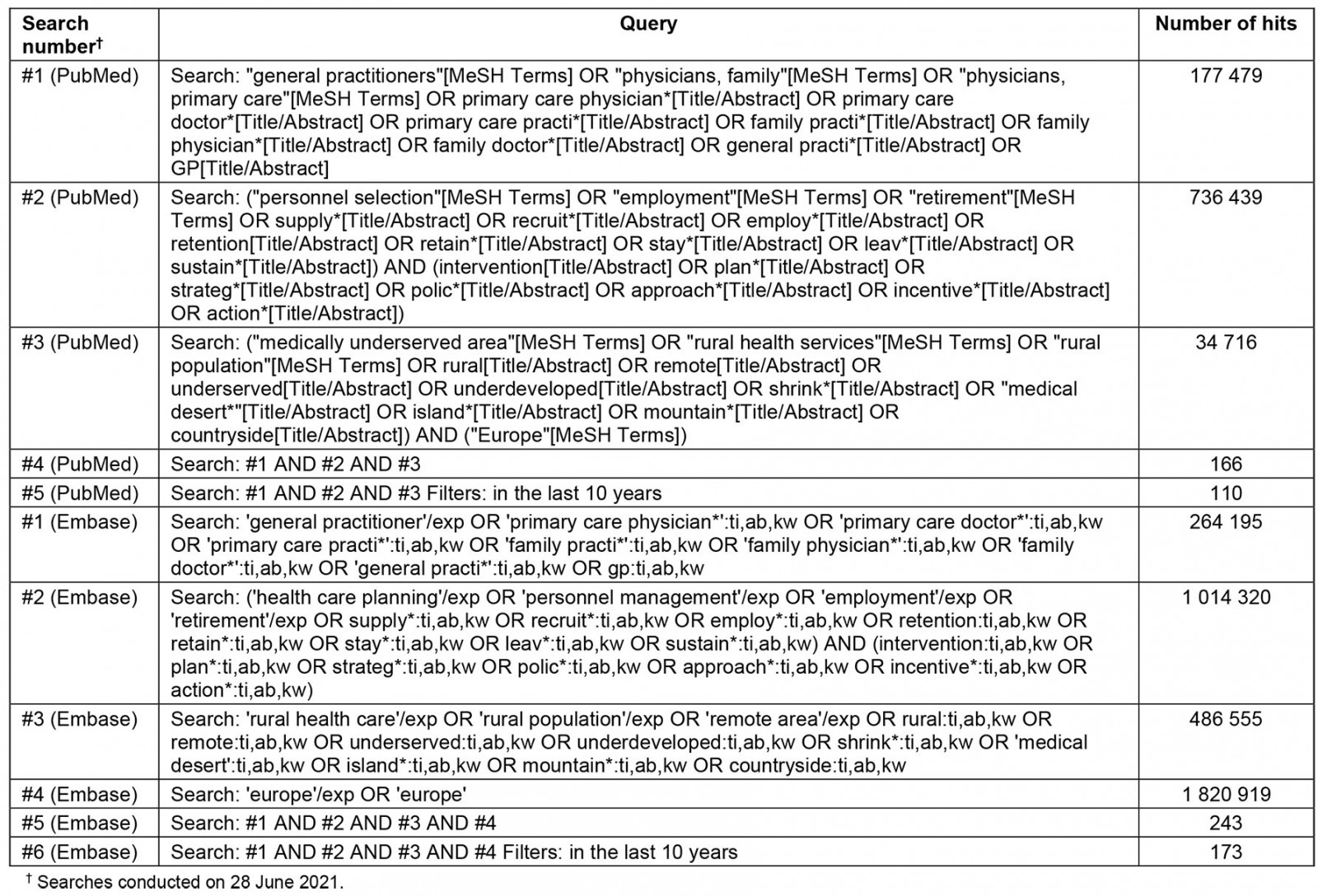

This review was conducted and reported in accordance with the PRISMA guideline (Supplementary table 1)11. To identify recent and relevant publications, two electronic databases (PubMed and Embase) were searched. For this, combinations of MeSH terms or Emtree terms, respectively, were used – as well as free-text words. The Boolean search string that was used is in Supplementary table 2. To identify any additional materials, national reports and implementation guidelines of European countries were searched. The Human Resources for Health and Rural and Remote Health websites were searched for publications. In addition to this, references of eligible articles were explored and added to the list. This search of databases and additional resources was performed on 28 June 2021.

Study selection

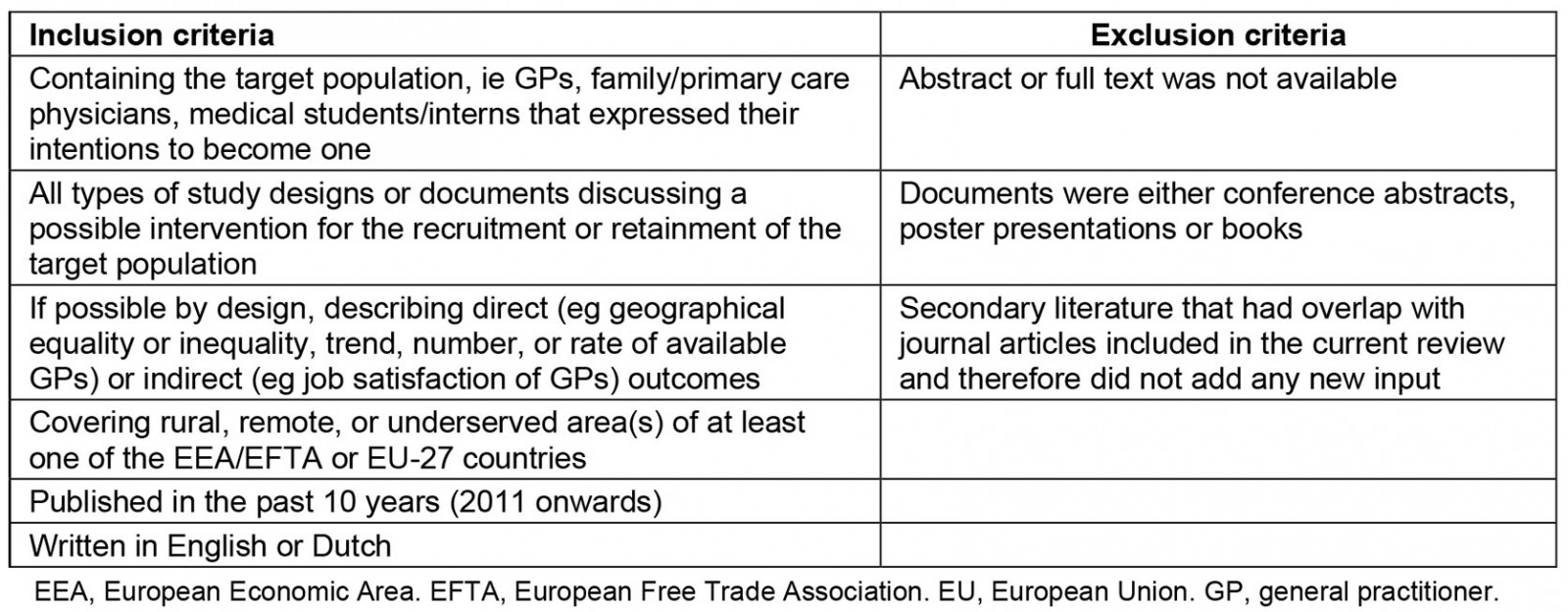

After retrieving articles and removing duplicate articles, the author (JB) applied a two-stage process for inclusion. First, titles and abstracts of all references found with the search strategy were screened against inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1). Then, the full text of articles was retrieved and assessed for eligibility against inclusion and exclusion criteria. Questionable articles were resolved through discussion among the authors (JB, LF, AIG, RB). Rayyan was used to facilitate the categorization and inclusion or exclusion of studies. Mendeley was used as a reference program to upload and organize the eligible articles and to read the full texts.

Table 1: Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Data synthesis and analysis method

All relevant articles were extracted into an Excel spreadsheet, including author details, year of publication, country, study type, setting or study population, recruitment or retention intervention(s), study findings or effectiveness, and category of intervention(s). If a publication did not evaluate, but only described, any effectiveness of their study intervention, the study finding was marked as ‘not evaluated’. The identified interventions were categorized by a framework, adapted from the global policy recommendations of the WHO8. This framework consists of four categories, including ‘education’, ‘professional and personal support’, ‘financial incentives’ and ‘regulation’.

Quality assessment

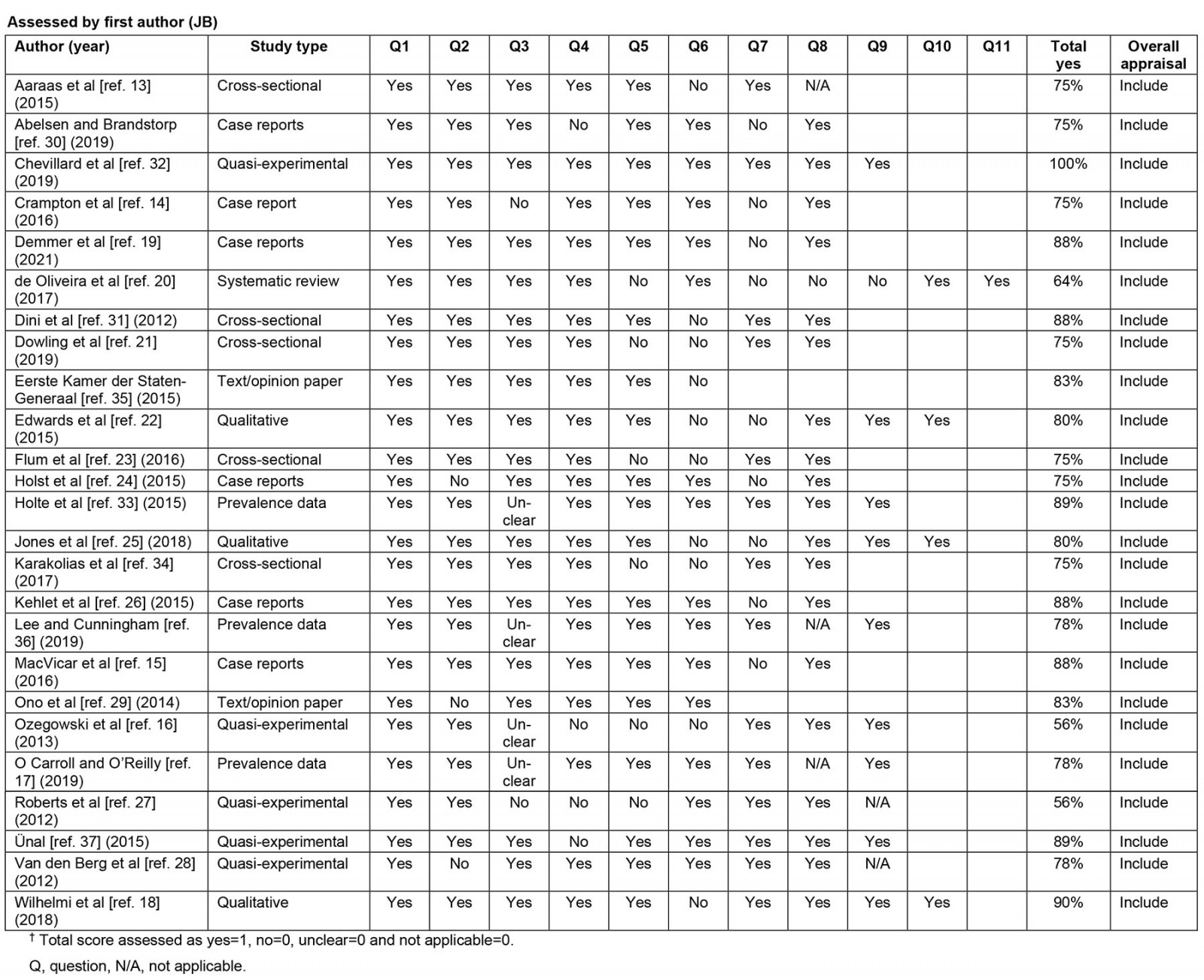

Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklists for the appropriate study design were used by two authors (JB, LF) independently for the critical appraisal of eligible studies12. Articles were included if they achieved a score above 50%. Disagreements were resolved through discussion (JB, LF, AIG, RB).

Results

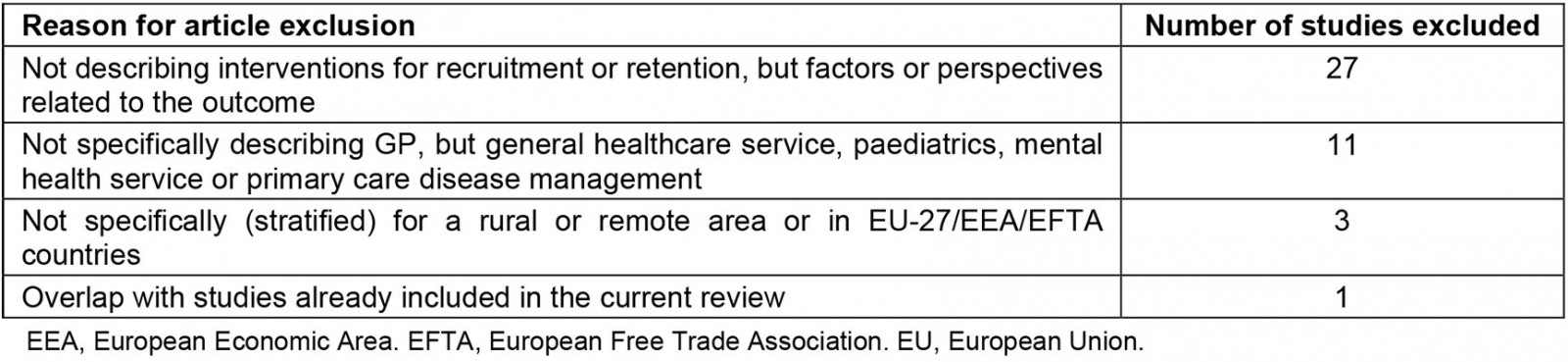

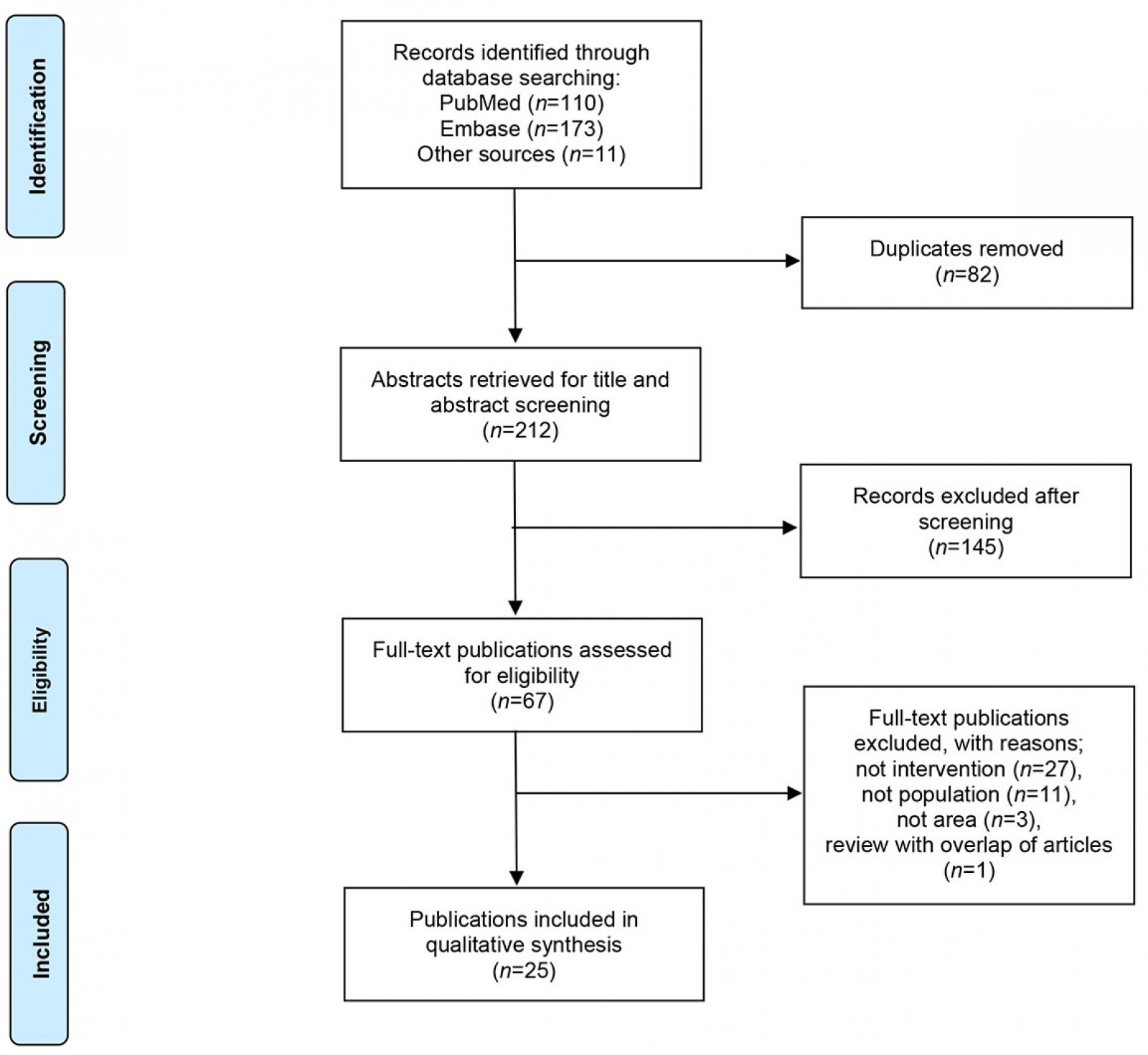

Figure 1 shows the selection process based on the literature search conducted. In total, the search (June 2021) resulted in 294 publications. After removal of duplicates, and title and abstract screening according to inclusion and exclusion criteria, 67 relevant publications remained. In the second stage, the full-text analysis, a total of 42 publications were excluded. Supplementary table 3 provides a detailed description of the reasons for exclusion. A total of 25 publications were included for the analyses. All met the JBI quality criteria for the appropriate study design, but most were of low methodological quality to assess the effectiveness of the outcome (Supplementary table 4).

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram of the publication selection process.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram of the publication selection process.

Study characteristics

Of the 25 included publications, the majority (n=15, 60%) reported on quantitative studies, seven (28%) on qualitative studies and three (12%) were policy reports or reviews (Supplementary table 4). Most of the included publications (n=23, 92%) concern West European countries, mostly the UK (n=6, 24%), Germany (n=6, 24%) and Norway (n=4, 16%). The population under study were medical students, interns or trainees (n=9, 36%) and GPs (n=9, 36%), of which one study included interviews with both. The remaining eight publications (32%) described municipalities, regions, or European countries more generally. An overview of the critical appraisal of the included publications is in Supplementary table 4.

Category of interventions

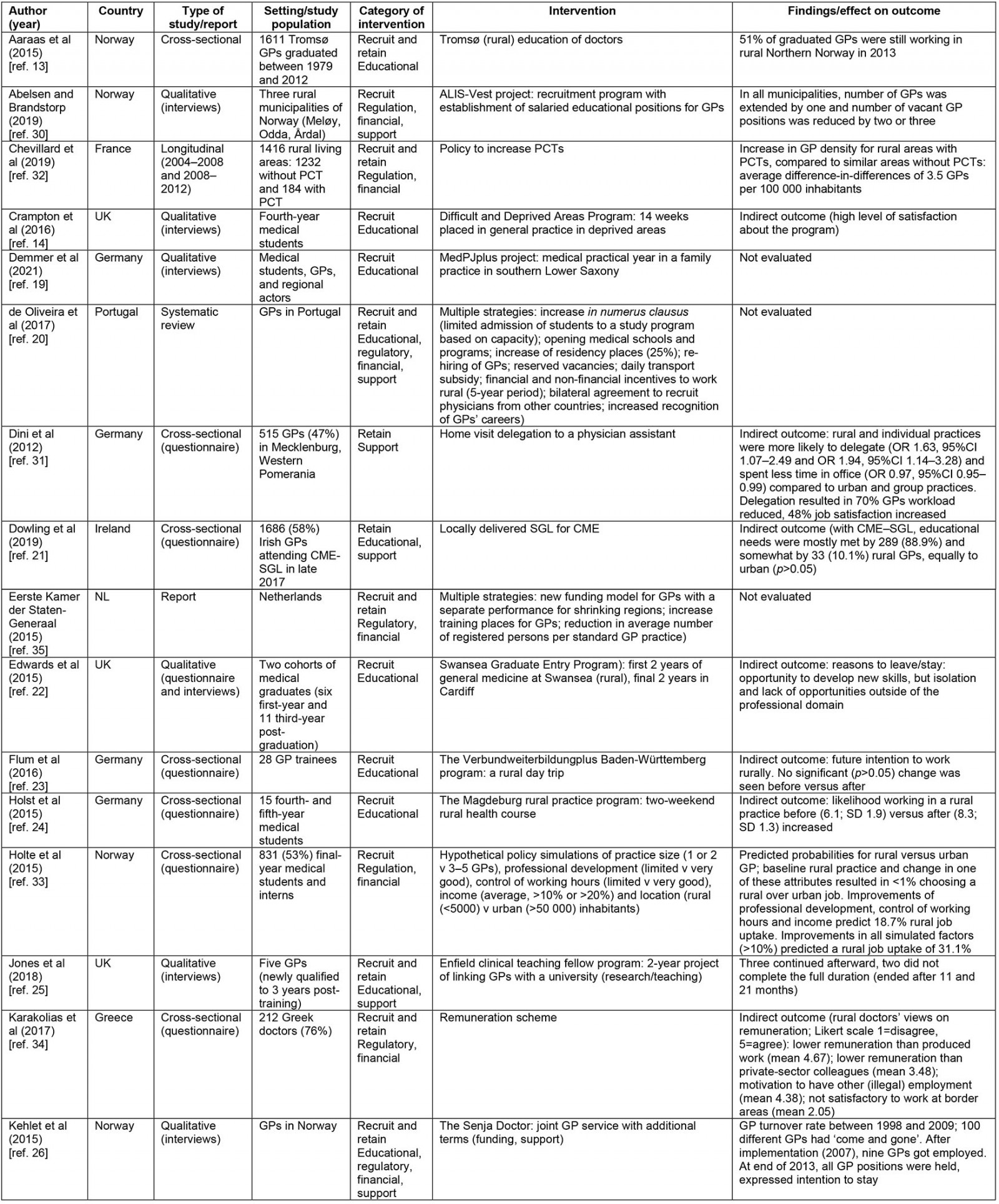

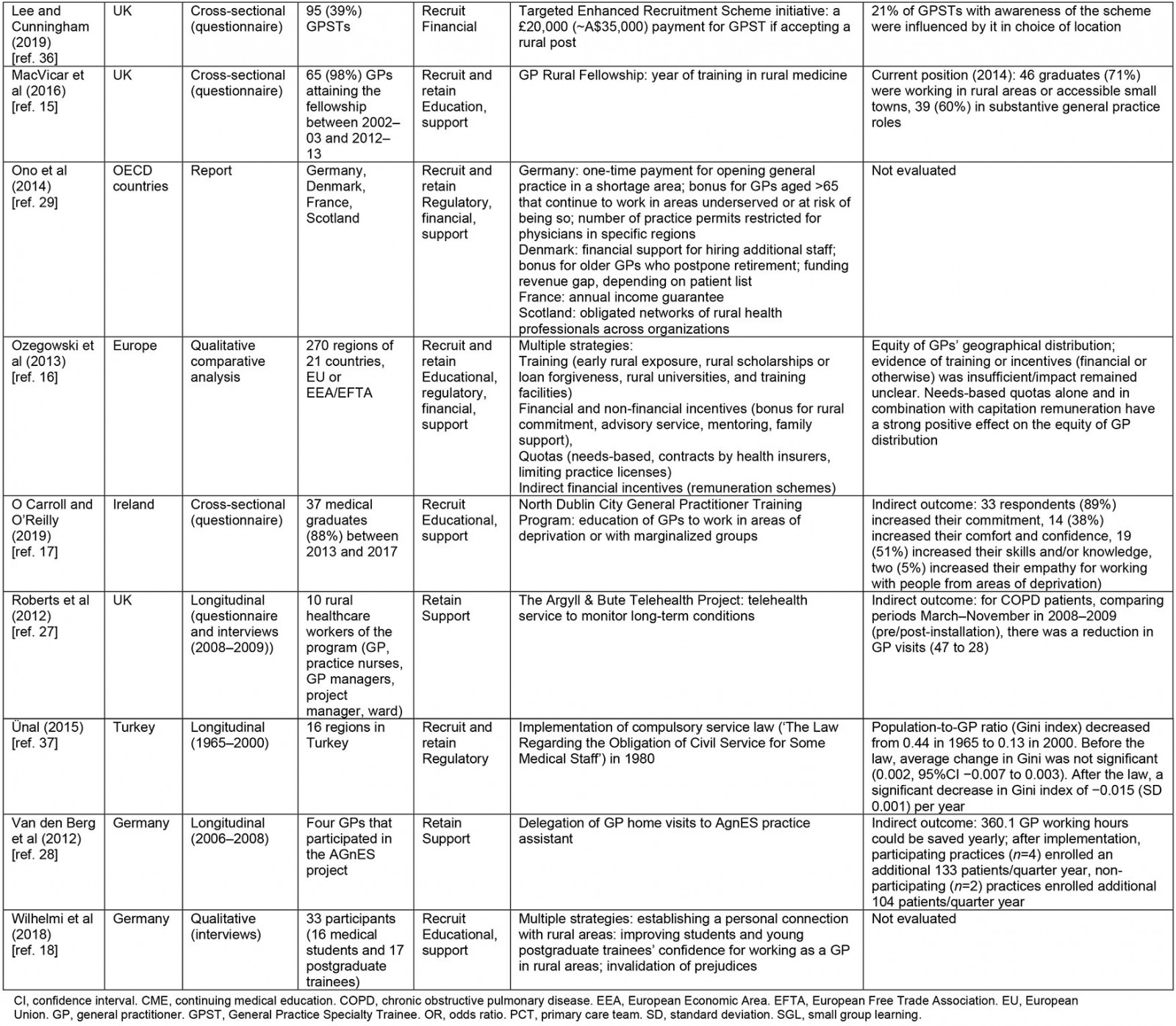

The included publications covered mostly interventions for GP recruitment (n=21, 84%) and, to a lesser extent, GP retention (n=15, 60%). Most publications (n=14, 56%) reported on multiple interventions or interventions, with overlap between four categories. A summary of the study findings, including categorization of described interventions, is presented in Table 2.

A majority of included publications (n=14, 56%) either described or evaluated educational interventions for recruiting and retaining GPs in medical deserts13-26. This varies from opening new (rural) medical schools13,20 to offering rural programs, rotations or internships to medical students14,19,22-24. The latter is reported in various forms, ranging from 1 day to a 2-year internship14,19,22-24. In addition, the option to let GPs in training conduct research (their doctoral thesis) or spend a ‘social year’ in a rural area is proposed to familiarize students with working in medical deserts18. For the retainment of GPs, multiple publications describe the provision of training and courses for GP career development15,17,21,25,26 – for example rural fellowships or training programs15,17,25,26 or small group learning that is locally delivered21.

Professional or personal support of GPs is described in 13 publications (52%)15-18,20,21,25-31. There is some overlap with the educational interventions to retain GPs as described above, through supporting further development and maintaining high professional standards15,17,21,25,26. Supportive measures, to counteract isolation are described as advising or mentoring rural GPs (eg with practice setup, location, background help)16,18, improving communication resources (eg internet, telehealth)18,27, task delegation28,31 within a general practice, or creating (obligated) networks of health professionals across rural organizations26,29. Furthermore, arrangements are described to reduce workload, including replacement for vacation or out-of-hours medical service (eg GP locum arrangements)18,26,30. In the area of personal support, offering extra vacation (days)16,20 or possibilities for family housing are described20,30.

Financial incentives are identified in 10 of the publications (40%). These are described in multiple forms and can directly or indirectly contribute to the recruitment or retention of rural GPs16,20,26,29,30,32-36. Direct financial incentives consist of an increased or guaranteed salary when GPs accept a job in a medical desert area29,30. In addition, offering a bonus is described: once in exchange for working certain years or several times20,29. This is proposed to trainees for accepting a rural training post20,36, but also to counteract early retirement of GPs in underserved areas20,29,36. Additional direct financial incentives (eg subsidy of transport and research funds) are mentioned to increase rural attractiveness20,26. Indirect financial measures include (co-)funding for hiring additional staff, closing revenue gaps or building new multi-professional group practices in underserved areas29,32. In addition, an alternative or ‘fairer’ payment system is described, such as adding a separate payment for individual general practices or regions26,35. Furthermore, changes in remuneration schemes, for example per patient or per service provided, are described16,26,34.

Several European countries reported their chosen or updated regulatory interventions (n=10, 40%) for the control of GP supply and demand in medical deserts. These interventions largely overlap with the abovementioned financial incentives16,20,26,29,30,32-35,37. Countries intervene by changing certain quotas16,20,26,29,32,35, such as an expansion of medical training places to increase GP supply29,32,35 or restrict the number of practice permits in certain regions to ensure a more equal geographical distribution of GPs29. In addition, a reduction in the average number of registered patients per standard general practice is applied26,35, aimed at reducing GP workloads. In France and Norway, governments opted for joint GP services by introducing regulations to stimulate primary care teams (eg co-funding of costs for establishing primary care teams)26,32. In Turkey, a law has been introduced that requires newly appointed GPs to perform a two-year ‘public service’: to work in a designated area determined by the health authority37. Some aforementioned educational interventions (fellowships) are also tied by regulation to a rural placement, often facilitated by financial incentives15,20,25. Furthermore, Portugal has opted for bilateral agreements that allow GPs from other countries to staff their rural primary care centers20.

Table 2: Summary of findings in reviewed literature

Effectiveness of interventions

In total, 10 publications (40%) evaluated the direct (potential) effectiveness of the described intervention(s) (ie the availability, density or distribution of GPs in the medical desert areas). In addition, certain indirect outcome(s)/factors of the outcome(s) were evaluated in 10 articles (40%). The remaining five publications (20%) did not evaluate their described or implemented intervention.

Although interventions were highly described, only nine publications had actually evaluated their educational intervention. For medical schools, it was found in a study in Northern Norway that more than half of the 1611 previously graduated GPs stayed working in this rural area13. In this study, a clear upward trend in physicians was observed since the start, but the design does not allow to conclusions on a causal relationship to be drawn. This also applies to other studies that evaluated different rural curricula by conducting single-time point questionnaires or interviews14,22,23. Indirect outcomes that were described in these studies showed high satisfaction with rural educational programs, or summarized factors that may have contributed to GPs staying or leaving a medical desert area. Despite reporting potential for their educational programs to recruit GPs, no further evaluation was conducted if this indeed resulted in an increase in rural GP availability. Two other studies, describing rural fellowships, did evaluate how many GPs remained afterwards15,25. One included five GPs with fellowships, and reported that more than half (60%) continued to work in the rural areas25. The other study questioned 66 GPs with fellowships, and found that 60% (n=39) had taken up a rural GP job15. Both studies did not take into account factors such as previous intentions or preferences to work rurally.

Two other published studies examined the drivers and barriers of educational programs during the careers of GPs, but without direct or conclusive results on the extent of contribution to the recruitment and retention of rural GPs17,21. A published study by Dowling et al showed that barriers to attend continued medical education were reported more frequently by rural GPs than by urban GPs21. In another publication, results of a survey among 42 graduates in a rural training program showed that respondents reported an increased commitment (89%) and skills/knowledge (51%), confidence and comfort (37%) to work in deprived areas17. The used questionnaire did not determine, however, to what extent this program resulted in actual rural job uptake in these regions. Ozegowski et al evaluated the overall effectiveness of the use of GP training interventions in 21 European countries. Their results on the (in)equality of distribution of GPs were inconclusive, due to a small sample of countries that actively used these interventions16.

Supportive measures to improve GP availability have been evaluated in only three publications. These studies did not show direct increases in the available number nor the reduction of GPs leaving medical desert areas27,28,31. Two of these studies examined the implementation of task delegation from GPs to qualified physician assistants in general practices in Germany28,31. The article by Dini et al showed that rural and individual practices were 1.6–1.9 times more likely to delegate compared to urban and group practices. As a result, the delegating GPs spent significantly less of their time on running their general practice31. The other study estimated that the implementation of the task delegation project saved approximately 360 GP working hours per year28. These researchers assumed that this, on the other hand, can be used to increase the number of registered patients per practice. After implementation, a higher average increase of patients was calculated in participating practices compared to non-participating practices (133 v 104 patients per quarter year, respectively). It should be noted, however, that practices in this study could allocate themselves to either the intervention or control group. This means that other influencing factors cannot be ruled out28. A publication on the use of telehealth in a Scottish rural GP practice highlighted that telehealth increased the interactional workability of the employed staff members. By monitoring patients remotely, fewer patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease visited the practice, but workload was not directly reduced through concerns with technical issues, although not quantified27.

Two publications evaluated financial or regulatory measures as recruitment or retention strategy solely36,37. One study on solely financial measures found that a £20,000 (~A$35,000) bonus to work in a certain rural area actually affected 21% of the trainees who were aware of this bonus36. No further investigation has been conducted into the extent to which these trainees already intended to work in such an area, regardless of payment, or on the effect on long-term stay. In relation to Europe, one publication showed that little to no relationship could be found between GP distribution and using financial bonuses as a singly policy measurement16. One study focused on a specific regulation measurement – the mandatory GP placement by law as introduced in Turkey in 1980 – and its impact on GP distribution over time37. The study showed that, after implementation, there was a significant average decrease in the Gini index (an indicator for regional maldistribution) in Turkey, which was not observed in the baseline trend before the law. This means that this mandatory law resulted in a rapid improvement of an equal GP distribution over the country, compared to only increasing the number of available GPs over time. More publications reported combinations of financial and regulatory strategies16,26,30,32-34.

Three publications evaluated remuneration schemes 16,33,34. One study found in a European context that the reimbursement of GPs using capitation payments (based on the number of registered inhabitants) had a positive effect on equal regional GP distribution. This effect was especially pronounced for countries with high GP density and in combination with a needs-based quota16. In Greece, a country with high variation in GP density, it was found that rural GPs, among others, agreed that the remuneration was not satisfactory to work at border areas34. This means remuneration influences their choice of location. In another study, simulations of policy measures, according to the preference of Norway medical students, showed that an increase of 10% in income on itself has little influence (0.02%) on the predicted probability of choosing a rural work location. Simultaneous improvement in other important attributes for location preferences (practice size, control of working hours and professional development) predicts a probability of 19% that medical students will choose a rural job over an urban job. On top of that, a 10% increase in income results in a predicted increase of up to 31%. It should be noted that these results are based on hypothetical simulations33.

A study in France quantified the impact of the ‘practice size’ over time (2004–2012) on GP retention in rural areas. It was shown that rural primary care teams co-funded by the government have higher GP density of 3.5 GPs per 100 000 inhabitants compared to similar areas without such primary care teams32. In Norway, it was found that the merging of rural GP practices, in combination with other beneficial (financial) incentives, resulted in fewer vacant GP positions and a reduction in turnover rate26,30. These studies show that ‘larger’ primary care teams slow down the decrease in GP density in rural areas. Other measures during these periods were not taken into account, however, which could lead to an overestimation of the results.

Discussion

This study provides a review of the literature from 2011 onwards describing and evaluating recruitment and retention strategies of GPs in medical deserts across Europe. We found that the most frequently reported interventions focused on education, and professional or personal support of GPs. To what extent these interventions have actually affected recruitment and retention of GPs in underserved areas is hard to conclude, since the majority of these studies were cross-sectionally designed, and via indirect contributing factors or not evaluated. Still, a number of publications showed that financial and regulatory interventions (financial bonus, a mandatory placement law or capitation remuneration) did have a pronounced effect on a more equal geographical distribution of GPs. However, since other confounding factors or co-interventions were not taken into account in these studies, a ‘best practice approach’ to recruit and retain GPs in underserved areas remains difficult to extract from our review.

Comparing existing literature

This research makes a contribution to the medical desert health workforce issue by using the framework prevalent in other literature38-41. Our results are in line with previous reviews that showed that educational interventions were most reported40-42. In this respect, this review complements these previous studies. Nevertheless, we found that multiple countries mainly reported a ‘rural curriculum’ as a solution for health workforce shortages. This could be for multiple reasons. First, the WHO, as well as the European Commission, has made a strong recommendation to implement this intervention8,43. In addition, adding a rural curriculum, especially in comparison to setting up rural medical schools, might be less resource demanding and costs are relatively modest. Although research suggests a strong association between rural exposure and choice of career location, results about the length of this curriculum are still inconclusive44-47. It is suggested that a longer duration (5–6 months) of rural exposure to students may be more economically sustainable45,46. The review of Peckham et al suggests, however, that increased duration can improve student skills or knowledge about general practice work in rural areas, but that this might not inherently translate into a higher recruitment rate47. Therefore, other intrinsic factors need to be accounted for as well. For example, in the USA and Australia, the personal interest of students in ‘rural medicine’ is explicitly screened by their medical school48,49. Evidence from these countries suggests that GPs with a rural background have a higher likelihood, approximately two times higher, of working in a rural practice50. The implementation of educational interventions thus involves several factors, which policymakers should take into account for recruitment strategies.

The present review identified multiple personal and professional support interventions that are aimed at improving working conditions. Research has indicated that multiple factors indirectly contribute to job satisfaction in rural areas, including manageable workload, support and the perception of a valued profession7,51. This might contribute to retaining GPs longer, or postpone their retirement. For example, continuous medical learning is of key importance for continuous professional development and job satisfaction, but flexibility is required to overcome barriers to attendance52. Research shows that telemedicine could also be a promising strategy for reducing workload and the retention of GPs, especially for rural and underserved communities53. This is in line with what our review shows and suggests that for the next-generation GP a healthy work–life balance is important. Multiple factors may contribute a small part to the reduction of GP shortage and unequal staff accessibility in underserved areas, and this substantiates the idea that a combination of measures should be used in retention strategies.

Nevertheless, there is still a lack of outcome-based evaluation studies that have investigated if, how and when educational and supportive measures are eventually successful to improve numbers of GPs in underserved areas – as emphasized previously41,42. This makes it difficult for policymakers to learn from implemented recruitment as well as retention interventions. A reason for this scarcity in evaluation studies might be the difficulty designing interventions and measuring causal relationships, since multiple factors (as already mentioned here) have to be taken into account. Also, direct outcomes are difficult to establish (eg difference in duration of employment, turnover rate), but measuring and analysing these are of great value54. However, these semi-experimental, longitudinal and outcome-precise studies are more time consuming and often costly to conduct. In addition, currently updated curricula or the use of telehealth might be ‘too new’ to be evaluated yet. In the meantime, the European Commission recommends their member states to update their training curricula and education to the rapid developments in health care. This might improve employability as well as equip GPs with the right skills for the current and future job market43. Therefore, indirectly evaluated outcomes, which are quicker and easier to measure in a shorter amount of time, are still highly informative to collect and review. Our study did this, and indicates the need for long-term evaluation of these interventions if policymakers want to respond adequately to rural GPs’ expectations and retention.

With regard to the role of financial incentives, few and mixed results were found when evaluated. This supports the conclusion of Verma et al, who reviewed US, Canadian and Australian recruitment and retention interventions9. They found that financial incentives were mainly effective for trainees with a rural background, particularly when there are flexible career opportunities and a longer period of obligatory service. On the other hand, policy simulations in Australia predicted as well that less than 1% of the working GPs would relocate in response to a hypothetical income increase of 10%55. This suggests that such an extrinsic motivation by financial incentive alone is not sufficient for trainees and GPs to move to underserved areas. One determinant we found little of in our review, but has been more addressed in studies outside Europe, is international recruitment9. This is often stimulated by higher salaries in neighboring countries. It is indicated that the migration of medical students or GPs to rural areas is mainly triggered by wealthier Western European countries, where a much higher salary than in their country is feasible20,56. Such bilateral or multilateral agreements might be a solution for the GP shortage in one country, but pose a problem to the country of origin. For example, Romania reported that approximately 14 000 GPs left their jobs in their national health system to practice abroad between 2007 and 201356. Although this might be efficient to address the GP shortages in the short term, cost-effectiveness of these measures of GP retention in the long term remains unclear. A study in England looked at the cost-effectiveness of a GP retention scheme57. Since GP training costs an average £11,600 (~A$21,000) per year and lasts approximately 4 years, retaining a GP employed in the health workforce for at least one additional year through a retention scheme (at £4430 (~A$8000) per year) can contribute to much larger financial savings. Although these results are country- or context-specific, this suggests that focusing on long-term retention of GPs in the health workforce could be more cost-effective for a national health system than increasing number of trainees.

Furthermore, our review found only a few publications on regulatory recruitment and retention measures, which might be because these are more demanding, economically as well as politically. Of these measures, the use of quotas to increase the number of medical students was most often described by countries. Previous research found that this has only a minor impact on the geographic distribution of GPs58,59. In Portugal, it was observed that, despite an annual growth rate of 0.94 to 3.57 physicians per 1000 inhabitants between 1996 and 2007, this did not lead to a more spatial distribution58. This corresponds to our described results in a publication on Turkey, before introduction of a GP mandatory placement law37. This contradicts the theoretical model in economics of supplier-induced demand – a larger supply of physicians resulting in a competitive medical market ensures that the demand for care and therefore the income per physician in these urban areas decreases60. This should make it more attractive to relocate to more underserved areas, where the demand for care and therefore also income is higher. One possible explanation for the observed trends by Correira and Veiga, and Ünal et al could be that the health labor market is not really competitive37,58. It could be that physicians themselves can stimulate the demand for care, and working in urban areas remains advantageous. Yet, there is disagreement on the importance and effect of this market failure60-63. Nevertheless, this substantiates that remuneration based on capitation payment could be effective, which is in line with our results.

We found robust evidence on the effectiveness of financial and regulatory measures, but the generalizability is challenging because there were a relatively small number of studies. One reason for this might be that countries often implement a combination of incentives and that measuring the individual effect of a regulatory measure is not possible. Although particularly the longitudinal studies of Ünal et al and Chevillard et al show valuable results, they could not adjust for co-interventions32,37. Because there is no uniformed European policy yet and often multiple simultaneous measures are implemented, the results of included studies are very country- and context-dependent. Also, medical desert areas within Europe have a relative definition. The desired distance to primary care could be country-specific; for a relatively small country such as the Netherlands, this will be shorter than for a larger country such as Norway. While this review mainly refers to rural areas, this does not automatically equate to underserved or deprived areas, but relatively often rural areas are underserved and a GP shortage is often first noticeable48.

The generalizability of our results to medical specializations other than GPs is also challenging. While some European countries offer patients a free and direct choice of medical care provider, others have a mandatory gatekeeping system by GPs to specialized care3. The latter requires a higher GP-to-patient density than that of specialized physicians in order to meet basic primary care needs. These country- and context-specific factors shows that further research is needed into the characteristics that define medical deserts. Caution is needed in relation to the transferability of our review findings, but could potentially give valuable information and mobilize health authorities of European countries for cooperation across borders.

Strengths and limitations

Our study reinforces the WHO framework that is often prevalent in literature on health workforce8,38-41. One strength of this systematic review is that it is focused on a key profession (GPs) in medical deserts, as health workforce shortages are often first noticeable in these areas. Previous reviews described the health workforces in general41,42; reviewing research on GPs only can offer insights into a more specific tailored strategy. In addition, we focus our review on extracting various outcomes of interventions, direct and indirect, and the effectiveness of the different recruitment and retention interventions. This variability provides additional understanding of factors influencing GP recruitment and retention in underserved areas. We also extensively searched grey literature, which has led to additional included publications. However, limitations should be taken into account when interpreting this review. We have used only two databases for our base search strategy.

Although no language restriction was used in the search string, a language bias may have occurred. The search for additional publications was only done in two languages (English and Dutch). Although GP shortages and unequal distribution are a problem across all European countries, our language selection might have unintentionally excluded, in particular, Eastern European studies. In these countries, policy and research outputs might only be written in their own languages and be less published locally and internationally. This suggests that our results might be more representative for Western Europe.

Our review was limited to publications that described or evaluated an intervention in their method or results section. Interventions could have been evaluated by countries but not published. Interventions mentioned in the introduction or discussion section have not been included, which might have caused a reporting bias, with some categories of recruitment and retention strategies being unrepresented in this review.

Conclusion

This systematic review contributes to the existing knowledge on recruitment and retention strategies of GPs in European medical deserts. While not all European countries were equally represented, these results remain of interest to those experiencing issues with GP distribution and medical deserts given a similar health system. Analyses of the selected publications showed that educational and supportive measures are most frequently reported, while often a multifactorial approach is described or implemented. Mainly due to limitations of the study designs and methodologies, the majority of interventions were not thoroughly evaluated on their effectiveness. Since the number and generalizability of published studies are not optimal, stronger focus on evaluation of the effectiveness of interventions is needed to provide policymakers with insight into the long-term sustainability of recruitment and retention interventions of GPs in medical deserts.

References

Supplementary material is available on the live site https://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/7477/#supplementary

You might also be interested in:

2021 - Grey nomads with diabetes self-management on the road – a scoping review

2015 - Obesity and obesity-related behaviors among rural and urban adults in the USA