Introduction

Death by suicide is a global public health concern, with nearly 800 000 people dying by suicide worldwide annually1. In Canada, where this study took place, approximately 4000 people die by suicide each year2, with an estimated 11 Canadians dying by suicide on any given day3.

Suicidality differs by age, sex, and occupation. For Canadians aged 10–29 years, suicide is the second leading cause of death, whereas it is the third leading cause of death for those between the age of 30 and 394. Canadian men and women who die by suicide tend to be middle-aged, and men who are either middle-aged or older have the highest rates of suicide5. Rural Canada has higher rates of suicide than its urban counterparts6-8, and increased suicidality has been found among agricultural, forestry, and fishery workers9,10.

Over the past decade, an abundance of quantitative research11-54 has been conducted to investigate rural suicidality in Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries. Upon examination of rural–urban suicide rate differentials in OECD countries – Austria22; Australia23; England24; Greece25; Italy26; New Zealand27; Norway, Sweden and Finland28, Scotland29, South Korea30, the USA31 and Wales32 – the risk for suicide is noted to be higher in rural areas.

White has contended that ‘traditional evidence-based reviews leave readers with an incomplete understanding of suicidal behaviors and a rather limited vocabulary for conceptualizing and representing preventative practices’ (p. 336)55. Moreover, White has maintained that such limitations can best be avoided through use of qualitative research methods capable of investigating the contextual, historical, and relational factors that influence the experience of suicidality55.

Qualitative suicidality research has not kept pace with that of quantitative inquiry. In fact, a review of suicidality research published between 2005 and 2007, discovered that qualitative methods were used less than 3% of the time56. A review of rural suicide research from OECD countries, published within the past decade, revealed a marginal uptick in qualitative investigation of rural suicidality, most notably within Australia, Sweden, the USA, and Canada. For example, qualitative research conducted in Australia has examined the experience of rural suicidality, with a particular focus on the bereavement experience of adolescents who had lost a friend to suicide57,58, the experiences of suicidality among Australian farmers and/or their families59-67. as well as rural men68,69. Research in Sweden has investigated nurses’ experiences of suicide risk assessment in rural mental health outpatient care units70.

Qualitative inquiry conducted in the USA has explored the mental health, wellbeing and suicidality of rural community residents, including children71, youth72, young adults73, transgender persons74, farmers75,76, and veterans77,78. Additionally, qualitative research endeavors have focused on the examination of rural suicidality prevention, intervention and postvention strategies79-85, including an exploration of the social and emotional needs of rural suicide survivors86.

In Canada, over the past decade, very little qualitative research has been done to investigate rural suicidality. In the studies conducted, the predominant focus has been on suicidality of men, specifically farmers, and youth. An exploration of how masculinities influence help-seeking among farmers, and the associations of rurality, farming, and masculinities in the context of men’s mental health built on previous research by providing ‘further evidence of the fluidity of masculine practices and their variability in different contexts’ (p. 9)87. After examining the connections between masculinity, farming, and health-promoting behaviors, researchers88 recommended that future research efforts be directed towards studying ‘how various positive masculine practices can be aligned with farmers’ health and well-being and that of their family’ (p. 1536). While investigating the psychological distress and suicidality of farmers, researchers89 identified the main causes and manifestations of distress as well as protective factors against distress in advance of highlighting the positive masculine practices that can improve mental health and wellbeing of farmers and their families. Based on these findings, researchers89 identified the development of a mental health plan for farmers as a national priority.

Minimal attention has been given to the perspectives of Canadians who have experienced suicidal ideation, attempted suicide, or lost someone to suicide. Among the studies that have been conducted, researchers90 used photovoice interviews with family members and close friends of a young man who had died by suicide and concluded that ‘community-based suicide prevention efforts would benefit from gender-sensitive and place specific approaches to advancing men’s mental health by making tangibly available and affirming an array of masculinities to foster well-being of young, rural based men’ (p. 617). In another study, researchers91 used photovoice interviews with family members who had lost a man to suicide to investigate contextual factors influencing men’s experiences of depression and responses to suicidal ideation followed by discussion of how gender relations and ideals of masculinity within rural settings are barriers to help-seeking behaviors.

More qualitative inquiry of rural suicidality in Canada is needed to further the recognition that those who have considered and/or attempted suicide are unique, multifaceted, and continuously evolving human beings92. A scant amount of Canadian research has focused on the lived experience of rural suicidality. With the aim of developing a research agenda for lived experience of suicidality in rural Canada, this study examined how rural Canadians understand their community values, what information gaps they identify in relation to current suicide research, and how research can be mobilized to reach rural communities.

Methods

Methodological approach

From March to May 2021, virtual focus groups were held in the Canadian provinces of Newfoundland and Labrador, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia. Focus group was chosen because the method can generate rich discussion about individual meanings and values while also providing opportunities to explore how meanings and values are produced and prioritized in a particular context93. Use of a virtual platform for focus groups became necessary when the COVID-19 pandemic precluded in-person meetings. The virtual platform afforded focus group password protection and permitted audio-video recordings of all focus groups. More information about the research inquiry method is available94.

Research inclusion criteria required that participants be Canadian and aged 18 years or older; reside in a rural community with a population of fewer than 10 000 people, or be either involved or employed in rural service provision within a community of fewer than 10 000. Participants were recruited through a purposive sampling strategy. Members of the research team identified various rural regional service centers and rural community organizations across Canada. In doing so, the research team considered demographic characteristics, economic drivers (eg industry, fishing, farming) and distance to urban areas to select diverse communities. Next, research team members emailed center/organization representatives in each of the selected communities with research project information. Those representatives who expressed interest in the research and agreed to collaborate assisted with recruitment of potential focus group participants. Rural community members who expressed interest in study participation were invited by center/organization representatives to contact an identified member of the research team for further information.

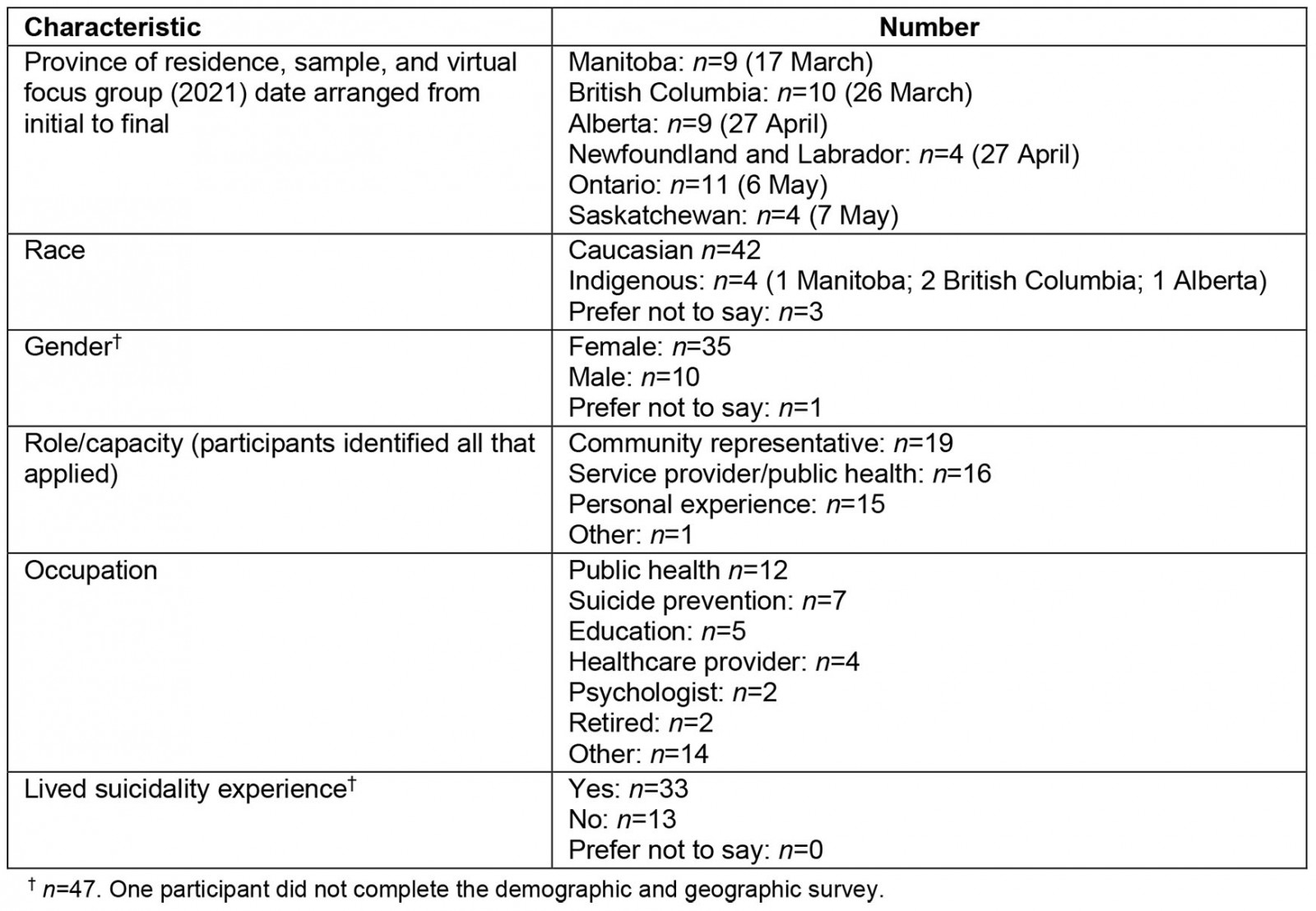

A total of 47 rural research participants agreed to participate in the research study; one participant did not complete the demographic and geographic survey distributed prior to focus group commencement. A total of 77% of participants were female, 22% were male and another 1% preferred not to say. With respect to race, 90% identified as Caucasian and 8% identified as Indigenous, while 2% preferred not to say. Attendees gave a variety of reasons for agreeing to participate in the research study, including being an engaged community member, or community leader; being a healthcare provider/working in the public health sector; and involvement in education, research, or other related fields. Regardless of their reasons for attending, 74% of the participants disclosed having lived experience of suicide, which for the purposes of this research study, was defined as either having attempted suicide or being close to someone who had completed suicide. Research participant demographic and geographic information is detailed in Table 1.

Researchers were concerned that the topic of suicide might be sensitive and/or triggering for some participants. Therefore, prior to participation in virtual focus groups, each potential participant was emailed information detailing mental health services, supports/resources; suicide supports/resources; as well as crisis support services and resources specific to and available within their province. Additionally, before commencement of each virtual focus group, all participants were invited to recall this resource material information and asked to access appropriate resource, should the need for any such support/service arise. More information about the research inquiry method is available94.

Table 1: Participant demographic and geographic information (n=46)†

Data collection

Six regional focus groups were conducted with participants from a specific rural area in each province. Focus groups ranged in size from four to 10 attendees and those with more than five attendees were divided into two smaller groups with pre-assignment of participants to breakout rooms. Research protocol did not involve mixing of focus group participants by location, and researchers did not pre-assign participants to focus groups with respect to employment or having lived suicidality experience. Anonymous collection of demographic data limited differentiation of persons with lived suicidality experience from those of health care, social and community service providers. Additionally, these were not mutually exclusive. During focus group discussion, for example, a number of healthcare providers disclosed having lived suicidality experience.

Each focus group session was conducted by 3–5 research team members, depending on the size of the group. While one research team member remained outside of the main room, available to assist any participant who might need to leave the focus group, two researchers were in each breakout room, with one taking notes and the other facilitating the group discussion94. To ensure consistency in data collection, all focus groups followed the same protocol. Each session began by orally reviewing the informed consent form sent to participants in advance of the focus group and providing opportunities for questions as well as allowing people to leave if they did not wish to participate. Demographic and geographic information (Table 1) was obtained from 46 of 47 participants, using anonymous survey, prior to virtual focus group commencement.

Data were collected to answer the research questions: What are the gaps in research investigating the lived experience of rural Canadian suicidality and what are the ways that future research can be mobilized for use by rural communities? A 20-minute PowerPoint presentation set the stage for each ensuing focus group. The purpose of this presentation was to share the findings of a Canadian scoping literature review recently completed with the aim of identifying existing research conducted to investigate the lived experience of suicidality in rural Canada. After the presentation, focus group participants were asked to consider: ‘Of the information presented, what is new or surprising to you? Based on the presentation, what research (information or questions) is needed to address suicide in rural communities? What would be the best way to get this information out to you and others in your area? How could this information be turned into action? or, who could turn this information into action?’ All focus groups were audio-recorded. Each focus group participant received a gratuity of a $20.00 Amazon e-gift card for their research involvement.

Ethics approval

Brandon University Ethics Committee approved this study’s research design and protocol (research ethics file number 22743) prior to research study commencement.

Transcription and analysis

All recordings were transcribed after the focus groups to ensure the confirmability of the research findings. Pseudonyms were also used to protect the anonymity for every virtual focus group participant.

NVivo v11 (QSR International; https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home) was used to manage the coding process. The entire research team, including senior and junior researchers from different disciplinary and professional backgrounds, coded an initial interview to develop a list of inductive codes derived from participants’ voices and personal priorities. This enabled the team to discuss and address coding inconsistences. Following the development of a preliminary codebook, the remaining transcripts were coded by two research team members. Having two coders from different backgrounds for all transcripts, including one consistent coder for all transcripts, helped to ensure consistency in both the application and the development of the code book as well as verify interpretations from different perspectives. Overarching themes and categories were identified by research team members. Codes and themes were finalized by consensus among all research team members.

Analysis of the focus group transcripts in relation to gaps in research investigating the lived experience of rural Canadians resulted in identification of one overarching theme – the need to humanize research – and three subthemes – recognition of the significance of rural culture and the experience of rurality; valuing the diversity, knowledge, and strength of persons with lived experience of suicide; and appreciation of the impact of suicide upon an entire rural community. Analysis of ways that future research can be mobilized in rural communities yielded three emergent themes: community engagement, timely access, and unique ways to disseminate information.

Results

Focus group participants eagerly shared their thoughts about what a lived experience research agenda should include. All participants provided insights into the unique needs of rural communities for research that is relevant to, and representative of, the diversity of rural people and places in Canada. Agreement resonated across every focus group that the voices of people with lived experience of suicide and rurality are largely absent from the research and that without these voices, suicide research is incomplete.

Gaps in research investigating the lived experience of rural Canadians

The need to humanize research: 72% of participants identified having lived experience of suicide as the main reason for agreeing to participate in the focus groups, and were adamant that the voices of persons with lived experience needed to be included in future research. Focus group analysis revealed the need for future rural suicidality research to extend beyond quantification by categorization, measurement, and replication to the incorporation of qualitative research methods recognized for the ability of providing insights into human experience. Numerous relational and contextual factors influence a person’s decision to die by suicide. A humanized approach to research investigating the influence of such factors on rural suicidality can capture the complex and diverse nature of persons with lived experience and detail rich descriptions helpful in informing public understanding, programs, and policies around rural suicidality.

One participant shared:

Hearing people’s stories and hearing their struggles and their survival and their ‘I’m still standing’ stories, that’s what helps people reach out because they see the value in reaching out. And the more we do it, the more it breaks that stigma down … Hearing from people who are survivors themselves, share those stories and how they deal with it … is huge and really, really huge, and that helps them. (Norm, ON)

Another suggested:

The qualitative angle, someone who’s come out of feeling suicidal and come out of it and what works for them … and maybe we need to try to find, to have more opportunities for survivors of severe depression or suicide that maybe they can help speak to those that are grasping. (Roy, MB)

Yet another affirmed:

I think that’s where the qualitative research comes into play is that it can tease out all of the things that were going on that person’s life including those big underlying factors like poverty and toxic masculinity has been mentioned and racialization, the impacts of colonization … oppression, all of those big picture things as well as what’s going on in the person’s own family, their own mental health, all of those things. (Jillian, MB)

Overall, research participants emphasized the need for future research to focus on the human dimensions of rural suicidality and in so doing investigate the strengths and knowledge that people with lived experience of suicidal ideation can offer their communities.

Recognizing the significance of rural culture and the experience of rurality: Research participants shared that any consideration of the experience of rurality must recognize that ‘rural’ people and places are not homogeneous entities. An overall lack of understanding by non-rural people of the significance of rural culture and the experience of rurality regarding suicidality was identified. Participants also spoke of the advantages and disadvantages of rural living, including the impacts of isolation.

One participant clarified:

Just because a community is rural, doesn’t mean every rural community has the same needs or has the same demographic. (Debbie, BC)

Participants shared the benefits and burdens associated with community living in rural areas that shape the ways rural residents engage with one another. The distinctness of rural culture and how urban service providers may be distrusted and viewed as outsiders was evident in the comment:

You’re not from here and you don’t understand their problems. You don’t understand what’s going on … You have to build up a whole lot of time before you are accepted as someone who might have valid input. (Amber, AB)

Focus group participants advised that research investigating suicidality must consider the significance of rural culture, including the experience of rurality. A pervasive mistrust of persons perceived to be outsiders was noted to be intrinsic to rural culture.

A participant shared:

… different language, a different level of trust [and that if he ever] tried to tell them what to do in their own farmyard or in their lives, I think there would be little bit of, thank you, but you don’t understand. (Gordon, AB)

Another participant spoke of being considered an outsider despite having lived in a rural community for several years:

I’m not originally from this rural community, I’m from another one and lived in an even smaller community than I’m in now, it was like, well, I’ve been here for four years. I only have another 20 before I’m considered a true local, like there is that sort of natural exclusion … It’s definitely like a level of exclusivity if you weren’t born and raised there. (Caroline, ON)

Participants spoke of the sense of community, the closeness, that is inherent within the rural experience.

One participant commented:

You need your neighbors; you need your family. It’s good and helpful to talk about this with someone. (Ronan, SK)

In contrast to the intimacy inherent within a sense of community, participants disclosed difficulties encountered while being a member of a close-knit rural community. Specifically, when information is shared privately among family, friends, and/or healthcare professionals, the person who has shared information is uncertain if it will be kept in confidence.

One participant clarified:

And word of mouth, you know? In a small community word travels fast. I know what I’ve done wrong before I’ve even done it. (Ava, BC)

Additionally, participants identified situations where persons contemplating suicide would complete the suicide in a location other than the vicinity of their home community.

Another participant shared:

They would either be in their vehicle, near a river, in an isolated area, in a motel room … people who specifically were not from the community, they weren’t living here per se, but they’d come to the community for the purpose of attempting or completing suicide. Many people in rural areas have family members who are mental health service providers or first responders, and they go to nearby communities to complete suicide so they will not be found by people they know. (Margaret, BC)

Overall, participants explained the value of close connections with neighbors and families in rural communities as well as the challenges that it posed for newcomers, service providers, and people experiencing suicidal ideation.

Valuing the diversity, knowledge, and strength of persons with lived experience of suicide: Research participants expressed the overall need for future research to value the diversity, knowledge, and strength of persons with lived experience of suicidality. Additionally, participants identified a lack of research aimed at suicide prevention in rural communities, resource development in rural communities, and reduction of stigma experienced by persons who express suicidal ideation and/or attempt suicide. Participants proposed using lived experience research as a basis for starting conversations around suicide to inform future development of suicide prevention strategies for rural communities.

One participant shared:

One thing that’s often missing from the research and the service provision kind of perspective is the voices of survivors of suicide loss, as well as people who have attempted suicide, because they have a lot to teach us around what that experience was like and what would make a difference to other people who are, you know, at risk. (Jillian, MB)

Focus group participants spoke of the significance for understanding the diversity of persons who inhabit rural communities. Research participants emphasized that current research is missing the voices of rural women, children, youth, seniors, Indigenous peoples, and people who identify as 2STLGBQ+ (Two-Spirit, Transgender, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Queer, Questioning) or non-binary who each have a lived experience of suicide. Concern was expressed that suicide research focused predominantly on men.

This concern was evident in the comment:

If we’re gonna act on this it means that we’re gonna start, just giving attention to men and what about all the women and non-binary people that might be suffering? I don’t know. (Roy, MB)

In addition, focus group participants voiced concerns that Indigenous people were underrepresented within the scoping literature review presentation.

One participant gave personal reasons for participating in the focus group:

We’ve had several suicides in [community] so I find that very distressing … It’s really hard to … I guess I’m just surprised that one group was included and a group with probably a lot higher numbers was not included in this study. That’s all I am going to say. (Camila, MB)

Another participant commented:

I think it’s really important to integrate the Indigenous communities into the research. I know it’s being done separately or however that plays out, but it’s my experience specifically in this rural community that it’s heavily populated with Indigenous folks. (Ava, BC)

Yet another participant emphasized:

I’m really interested in other, and more information about the other Indigenous research. I’m thinking about research that will cover sort of risk factors or preventative factors, I think that some of the other things we talked about ... around poverty, housing – again like just the basics of like thinking that it would be a different demographic of people that – yeah would be helpful. (Lily, BC).

Concern was also expressed about the potential to miss important lived experience perspectives if Indigenous people who live off-reserve are not included in research.

A participant emphasized:

There’s tons of Indigenous folks, that if we’re not capturing them within the scope of the actual community and only going on-reserve, then you’re missing a whole bunch of people. (Mary, BC)

It is important to note that numerous participants indicated that the lack of Indigenous suicide research represented a significant gap in the literature. This gap in the suicide research literature is reflected in real-world implications for service provision deficits, program planning and delivery deficits, as well as a host of unmet intervention and postvention needs of Indigenous communities who are simultaneously dealing with suicide loss aftermath. The concerns expressed by participants reflect the growing understanding of the disproportionate impact that suicide has on Indigenous communities in rural and remote places.

To understand the scope of the lived experience of suicidality in rural communities, it is particularly important to hear the voices of rural Indigenous people. Although Indigenous people are part of rural communities, they experience distinct challenges in rural community contexts. Focus group participants recommended that Indigenous experiences and rural suicidality not be segregated into separate research areas. However, for Indigenous stories and experiences to be incorporated into future suicide research, care must be exercised to ensure that research is conducted in a respectful manner; research should be led by Indigenous researchers while incorporating the wisdom of Indigenous knowledge keepers and community members. Moreover, settler researchers must adhere to the First Nations principles of ownership, control, access, and possession of data (OCAP)95, and data collection processes during research conducted within their communities.

Appreciating the impact of suicide on an entire rural community: Research participants identified a lack of research examining the impact that suicide has upon an entire rural community.

Several participants shared the extent to which a completed suicide affects not only the immediate family but every rural community member:

… what I’ve seen, huge issues with Indigenous populations and how those communities have been rocked over many decades. And in my experience a loss of identity, loss of life within those communities and what that impact that sort of ongoing trauma has to the community … the ongoing impact becomes for the surviving members of those families and those communities and what that feels like when you enter that community. If you attend for a funeral where there’s been a suicide it really – there’s this huge pain that I think is just part of the fabric that they’ve had to live with. (Margaret, BC)

The impact is broad, so the second anyone within the community has committed suicide … the waves go out through the rest of the community. (Lily, BC)

Another participant disclosed feelings associated with learning about a death by suicide in the community:

It’s frustrating to me when I hear about it happening because there are resources here, and there’s lots of people who were working, very close-knit community, and there’s a lot of community members, and like everybody else, they love each other for the most part. (Jeremy, NL)

Yet another participant emphasized that the impact of a death by suicide in rural communities cannot be overstated:

The community trauma that happens when one person dies by suicide is huge. (Jillian, MB)

Still another participant shared how people within rural communities who have experienced the death of a family member by suicide become:

a community within itself … we’re not just talking about the person directly involved in the loss, we’re talking about the full and complete fallout of the actions of losing someone by suicide. And it is profound. (Camilla, MB)

Together, these comments speak to the need for bereavement supports specific to rural community contexts.

Ways that future research can be mobilized for use by rural communities

Community engagement: A significant attribute of rural communities is the way community members often come together to support one another in times of need. Participants acknowledged that strong relationships among community members are critical to the success of community engagement. They spoke of the desire to use relationships that already exist to foster community partnerships and communities of support.

One participant suggested:

Just to leverage those relationships that already exist. And definitely to get the buy in from the community, because that’s who the community trusts are their fellow residents and the neighbors and their cousins that live down the road and everything else and primary care. (Jaimie, ON)

Participants further suggested that successful community engagement requires community leadership and someone to champion the cause. While speaking of suicide survivors, one participant suggested: ‘That person could be an ambassador, you know, a flag bearer’ (Roy, MB).

Another participant affirmed:

So, you know, if you have a champion, a champion in the community, it makes a difference. (Amber, AB)

According to participants, the impetus to participate in discussions with outsiders about rural suicidality, suicide prevention, and interventions research must come from within the rural community itself. Moreover, hesitancy for entering conversations with outsiders can be overcome only when relationships with community members are cultivated, and existing connections nurtured.

One participant emphasized:

What we really want is that connection, we want that community connection, and we want the ability to have them [researchers] let us know. (Raymond, MB)

Above all, participants identified the desire to effect change in their rural communities and challenged each other to consider how to get their communities engaged. Their solution for facilitating engagement was to share information, to have difficult conversations, and to pair these with an ‘invitation to action’.

Another participant imagined the ‘invitation to action’ as challenging the community to think about things they could do to improve the ways in which information about suicide research is shared and implemented:

How do we get communities to start getting engaged, like the information getting shared, get paired with an invitation to, have you thought about this? Have you thought about how you could effect change in your community? What are some of the things you think you could do? (Kendall, ON)

Timely access: Research participants identified the need for timely access to relevant rural suicidality research. Frustration was expressed with delays in access. Concerns were shared that by the time that research becomes available, it might not be up to date or be relevant to rural settings, and/or the information may not provide practical, implementable solutions. Participants stressed the importance of information that can be utilized by community for community; research must be relevant to rural communities.

One participant shared:

And I’d also like to see that the research is made available, doesn’t sit on a shelf in the university, but is made accessible to people in, you know, just via all the channels that we know work: social media, community newspapers, profiling people’s stories, the arts, you know. (Jillian, MB)

While discussing the need for timely access, a participant stated:

So, they say take seven years from research to gather the research until it’s published. So you know, if there’s any way that we are able to speed up that process or be more transparent and open with people, I think, you know, the more information you have, sometimes the better, the more beneficial it can be. (Dahlia, NFL)

Unique ways to disseminate information: Rural communities each have unique ways for disseminating information. Knowledge of the various methods used by rural communities for sharing information is critical to ensuring that residents become informed about available services, programs, and initiatives. Participant suggestions for increasing accessibility of research and resources by rural people ranged from utilizing local newspapers and radio broadcasts, to posting on social media, hosting podcasts, and sharing with parent councils, and local church and service clubs.

One participant suggested connecting:

… with the Rotary, and the Lions club, and the local groups, and the police … it would help us to then move it around the community and use it as well for planning purposes. (Callie, ON)

Yet another identified:

Your hockey coaches, it’s your figure skating coach, sports groups, baseball, service clubs. We do still have, they are aging, but strong service members and then our church groups as well. (Erin, ON)

Discussion

In this qualitative study, analysis of findings about gaps in research investigating the lived experience of rural Canadians revealed one overarching theme – the need to humanize research – and three subthemes – recognition of the significance of rural culture and the experience of rurality; valuing the diversity, knowledge, and strength of persons with lived experience of suicide; and appreciation of the impact of suicide upon an entire rural community. Emergent themes of ways that future research can be mobilized for use by rural communities included community engagement, timely access, and unique ways to disseminate information.

Research findings identify that the humanizing lens intrinsic to qualitative inquiry is necessary to capture the rich, narrative data that can only be obtained by listening to people with lived experience of rural suicidality. Although the significance of rural culture and experience of rurality to rural health is well known, this study’s findings point to an existing gap in the recognition of rural culture and community uniqueness that includes an understanding of the interplay between suicide, rural residence, and community. Consistent with previous literature on mental health and rural culture90,91,96, this research study findings suggest that rural culture may affect help-seeking behaviors of persons contemplating suicide as well as influence the determination of the location for attempting or completing suicide.

Current research gaps can be addressed by studies exploring the relationship between suicidality and rural culture for the purpose of understanding the ways in which the experience of rurality contributes to, and mitigates, suicidal behavior among rural residents. Given that the diversity and complexity of rural life shapes individual and community responses to suicide, findings also support the need for future research that considers the contextualized experiences of rural women, children, youth, seniors, Indigenous peoples, and people who identify as 2STLGBQ+ or non-binary.

In addition to identifying the need for access to appropriate mental health services, research findings reveal that the strength of rural communities is its residents. Such findings suggest that future research endeavors should capitalize on this natural, available source of strength to promote community engagement. Findings further support the need for timely access by rural communities, to current, relevant research about rural suicidality. Ultimately, research findings recommend that future research should be action oriented, driven by community needs, to not only promote community participation, but also seek sustainable rural community solutions.

Strengths and limitations

Drawing together the perspectives of six geographically diverse rural communities located in six Canadian provinces was a strength. Although inclusion of people with lived suicidality experience was another strength, anonymous collection of demographic data limited differentiation of the voices of persons with lived suicidality experience from those of health, social, and community service providers. Moreover, the inability to pre-assign participants to homogeneous focus groups, ie assignment of persons with lived suicidality experience to one focus group and healthcare providers to another group, may have influenced the way in which persons with lived experiences responded by imposing limitations on their willingness to express ideas and experiences freely. This limitation may in turn have affected data generation and interpretation.

The multidisciplinary backgrounds of research team members, with representation from nursing, psychiatric nursing, and health geography, added depth and breadth of suicidality knowledge and experience to the research, focus group sessions, as well as data analysis.

This study was limited by the need to conduct virtual instead of in-person focus groups. Specifically, internet connection instability in some rural areas was a barrier for holding virtual focus groups. In contrast, a strength of virtual platform use was the ability of the researchers to facilitate all focus groups and for all research participants to meet virtually from a location of their choosing, without the need to travel. Moreover, the use of virtual focus groups may have promoted both physical and/or emotional safety for participants by providing a measure of anonymity while participants engaged in discussions about the sensitive and emotionally laden topic of suicide.

Although a strength was the relatively diverse composition of focus group membership, the preponderance (77%) of Caucasian female participants may have limited the voices from rural men, recognized to be an at-risk group. Further limitations were exclusion of French-speaking communities and the territorial north from data collection, as well as a lack of representation of Indigenous and remote communities.

Ultimately, this study was limited by lack of inclusion of the literature on suicidality in rural and remote Indigenous communities. A significant amount of work led by/produced in partnership with Indigenous scholars and experts has been done in this area97,98. Although this literature was excluded from the scoping review conducted for the purpose of this study, it is important to acknowledge that a targeted review of Indigenous-specific literature would have revealed more extensive knowledge and publication in this area.

Conclusion

OECD countries have diverse rural places and people. As such, future endeavors should build on existing research by using qualitative inquiry to fully investigate the lived experience of rural suicidality. Available suicidality research does not meet the needs of rural Canadians. Despite the importance of rural culture and experiences of rurality, the voices of those with lived experience of suicidality are missing in current Canadian literature. The stories of Indigenous people, women, girls, and sexual minorities in rural Canada with lived experience of suicide need to be shared. Given the diversity of rural Canadian communities, a future research agenda with the aim of investigating rural suicidality with its associated impact upon rural communities and members must reflect this diversity. Rural residents desire research that involves and benefits their communities. As such, future research efforts must be action oriented, participatory and community based.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada (Contract).