Introduction

Missouri Bootheel counties (Dunklin, Mississippi, New Madrid, and Pemiscot) are in the south-easternmost area of Missouri, USA. These counties experience some of the worst health outcomes, with all four counties falling in the lowest 5% of the overall health rankings across 115 Missouri counties (Dunklin rank 112, Mississippi rank 114, New Madrid rank 111, and Pemiscot rank 115)1. The average life expectancy at birth for the residents in these four counties is 72.3 years, which is roughly 5 years less than the state overall (77.3 years)2. These residents have limited access to healthcare services, which is due in part to a lack of providers. For example, the ratio of population to primary care physicians in Mississippi County is 6670:1 and in New Madrid County it is 17 300:1, while the overall ratio in the state of Missouri is 1420:13. There are also significant gaps in access to dental care and mental healthcare providers compared to the rest of Missouri and the USA4,5. Moreover, access to healthcare resources is unevenly distributed within these counties, with primary care services and other providers being located in the county seats and virtually no care in outlying areas6.

These poor health outcomes and lack of access to health care are also due to social and economic circumstances that influence community members’ ability to prevent illness and disease, detect health issues, successfully navigate the health system, and effectively manage health issues7-9. Although the average high school graduation rate in these four counties is higher than in the State of Missouri (94% v 91%), the percentage of the population aged 16 years and older who are unemployed is significantly higher than the state average (4.7% v 3.3%)10,11. This higher rate of unemployment can be related to a lower average median household income in these four counties compared to the state average (US$38,025 vs US$57,400) and a higher percentage of uninsured adults under the age of 65 years (14% v 11%)12,13. Problems accessing health care are further compounded by the lack of broadband access, which is about 72% in these four counties compared to 80% in the State of Missouri14.

While this data points to the existence of significant needs, it does not provide a clear understanding of the issues, and the actions that can be taken to mitigate these challenges. Thus, community engagement is critical to developing a comprehensive understanding of community problems in ways that can lead to feasible strategies for change15. It enhances the potential for data collection, analysis, and interpretation to produce actionable results, and improves the dissemination of research findings to real-world settings. Additionally, community engagement fosters mutual trust among agencies, service providers, and community members to make research questions more relevant to community members and service providers. It also helps researchers develop novel community-based interventions by facilitating the inclusion of community perspectives in all phases of research16.

Furthermore, there is a lack of sufficient inclusion of social determinants of health in clinical health management, which can be attributed to a deficit in organization-level policies and procedures. While there is an increasing trend toward screening for and addressing social determinants in clinical healthcare settings, it is important that the community are engaged to provide their perspectives17.

The broad goal of the research collaborative was to increase social capital and infrastructure for community activation by engaging community members and practice partners in a participatory process to increase understanding of the organizational and social determinants influencing access to health care in the Bootheel counties and collectively recommend strategies for change. The specific purpose of this study was to compile and synthesize secondary data, collect new data, and develop a set of strategies to address identified priorities influencing health and equity.

Methods

A concept mapping approach was implemented to collect and analyze community views regarding various social and organizational determinants of access to healthcare services in four rural counties, prioritize these determinants, and recommend strategies for change. Concept mapping is a stakeholder-engaged approach to the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data in a phased sequence: a) community preparation, b) community brainstorming, c) community sorting and rating, d) multivariate statistical analyses, and e) community interpretation/utilization of results18. Each of these steps is described below. These steps provided a systematic mixed-methods structure through which community members and agency representatives could be involved at every stage of the study.

a) Community preparation

This study began by asking community members in the four-county area about their main health-related issues and concerns. As a result of this ‘listening tour’, access to health care was identified as a key issue facing these communities. University and practice partners collected secondary data regarding key social and organizational factors influencing access to healthcare services in these areas, including transportation barriers, cost of care and insurance, and lack of healthcare institutions and professionals. These data were presented to community and practice partners during multiple community forums. While the data presented were seen as valid, they were deemed insufficient to guide interventions. The data were seen as failing to capture individuals’ lived experiences in ways that are critical to crafting sustainable and effective strategies. With the help of local community health workers (CHWs), we created a process to identify participants, collect additional data, and use that data for the development of recommendations for change.

b) Community brainstorming

Brainstorming data were collected from various community members and agency representatives (n=368) through facilitated community forums and an online survey (Appendix I). Special attention was given to ensure proper representation from all four counties, hence at least one community forum was held in each county ‘seat’. In addition, CHWs traveled to area community centers and faith-based organizations to meet with groups and individuals. Participants (including community members, teachers, city officials, regional/state officials, police, social service and public health employees, medical providers, pharmacists, childcare providers, and for-profit businesses) were invited to share their ideas in conversations with each other and CHWs or through an online survey (Qualtrics link was provided in a variety of formats – online, through a QR code, and as a weblink on flyers distributed throughout the community). Participants were asked to complete a demographic survey to characterize the sample.

Data collected from community forums (632 statements) and the online survey (868 statements) resulted in a total of 1500 statements. Researchers then consolidated the statements by removing duplicates and overlapping statements, resulting in 72 unique, representative statements.

c) Community sorting and rating

This list of consolidated statements was then entered into the online concept mapping system The Concept System® Global Max© v2021.224.12, (Concept Systems Inc.; https://conceptsystemsglobal.com/index.php). The consolidated set of statements was sorted by 44 community members and stakeholders, comprising equal numbers of individuals from each county, ensuring proper representation from all four counties. Additionally, participants who were involved in the sorting and rating phase were from diverse backgrounds such as education, city officials, state officials, police, social service, churches, public health, medical, senior services, childcare, non-profits, for-profits, and local community members.

Participants were asked to sort statements into like groups according to their conceptual similarities and to rate the importance of each statement on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (‘not at all important’) to 10 (‘extremely important’). Participants also completed a demographic survey to characterize the sample.

d) Multivariate statistical analyses

Using standard methods ( similarity matrix creation, multidimensional scaling, hierarchical cluster analysis, and cluster map formation), these sorted statements were combined into nine groups or clusters and presented as a concept map depicting the main clusters and their conceptual proximity to one another. To determine a final cluster solution for the cluster prioritization phase of the study, clusters were analyzed starting with a 12-cluster solution and working downwards as clusters merged. The statements in each cluster were examined to ensure that clusters that were merged contained conceptually similar concepts. The final nine-cluster solution was chosen by the consensus of the authors to balance the adequate description of key issues and parsimony.

e) Community interpretation/utilization of results

These clusters of statements were presented at community forums in each participating county during which meeting attendees (community members and multiple stakeholder groups in each county) discussed the extent to which these represented the key issues facing the communities and prioritized which of the clusters they wanted to work on initially.

Participants were convened and a nominal group technique was used to prioritize which cluster to focus on to bring change. Some criteria for prioritization of clusters were presented by the researcher to the group, such as the importance of the issue and the potential to create change, while other criteria were self-identified and discussed by the meeting attendees, such as communal and organization support to address the cluster/issue, cost, flexibility, complexity, time, and potential impact.

Each participant was then asked to pick the top three clusters on which to focus for strategy development. Individual priorities were collected anonymously and then tallied, allowing a group ranking of the top three or four priorities for that county. After prioritizing these areas for improvement, participants were asked to discuss, and brainstorm additional details including existing resources and recommended strategies for addressing those prioritized issues.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Saint Louis University Institutional Review Board (IRB# 29719).

Results

Characteristics of participants in the community brainstorming phase

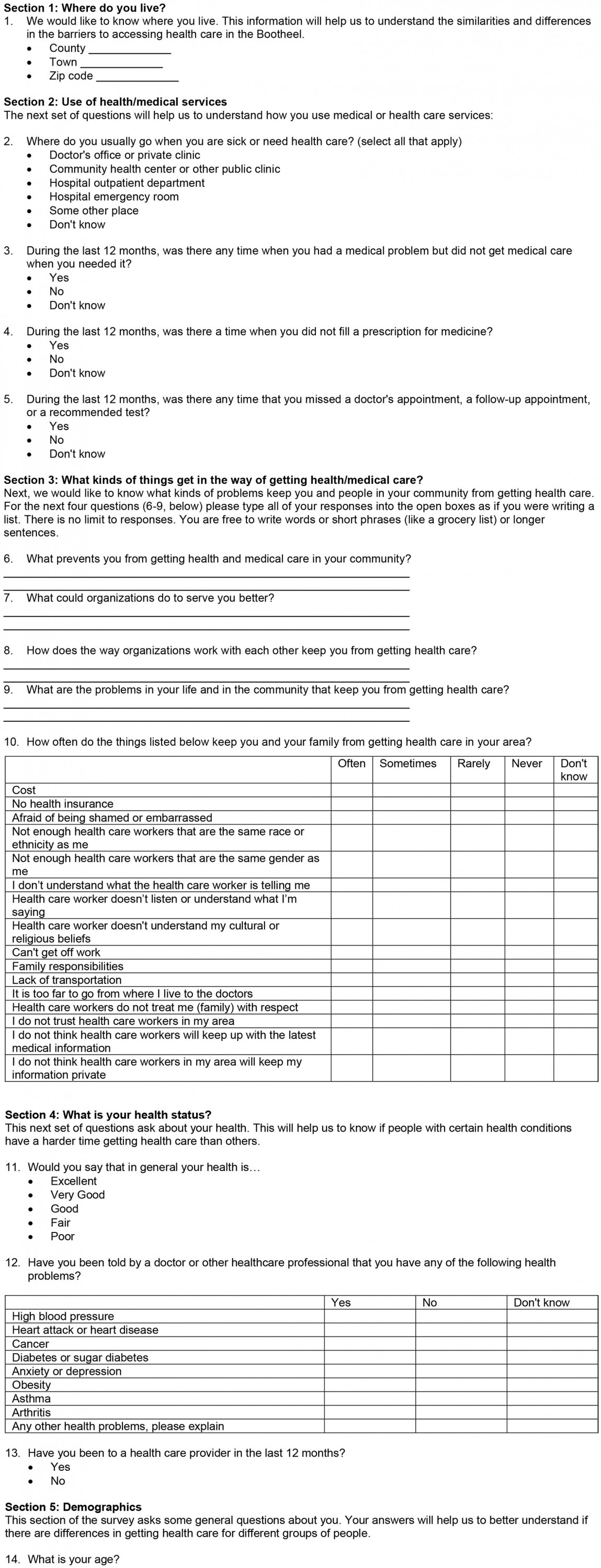

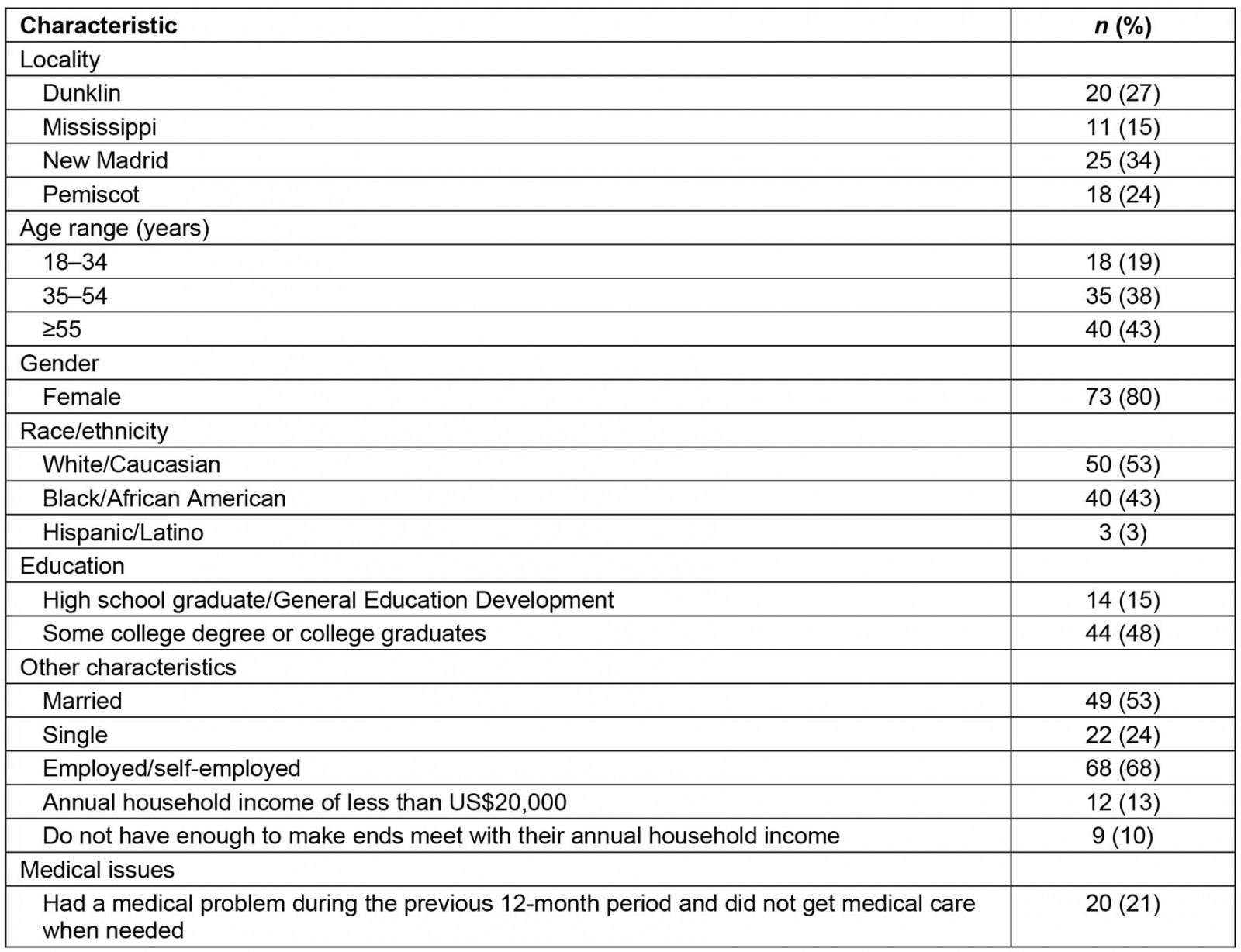

A total of 368 respondents from all four study counties (Dunklin 21%, Mississippi 43%, New Madrid 19%, and Pemiscot 17%) participated in a brief survey during the brainstorming phase of the study. Among them, 72% were female (in comparison to an average of 51% in the area), 37% were Black/African American (in comparison to Dunklin 10%, Mississippi 25%, New Madrid 16%, and Pemiscot 27%), and 5% were Hispanic/Latino (Dunklin 7%, Mississippi 2%, New Madrid 2%, and Pemiscot 3%)19. Additional demographic and other general information about these participants is given in Table 1.

Table 1: Characteristics of participants in the community brainstorming phase of the study

Characteristics of participants in the community sorting and rating phase

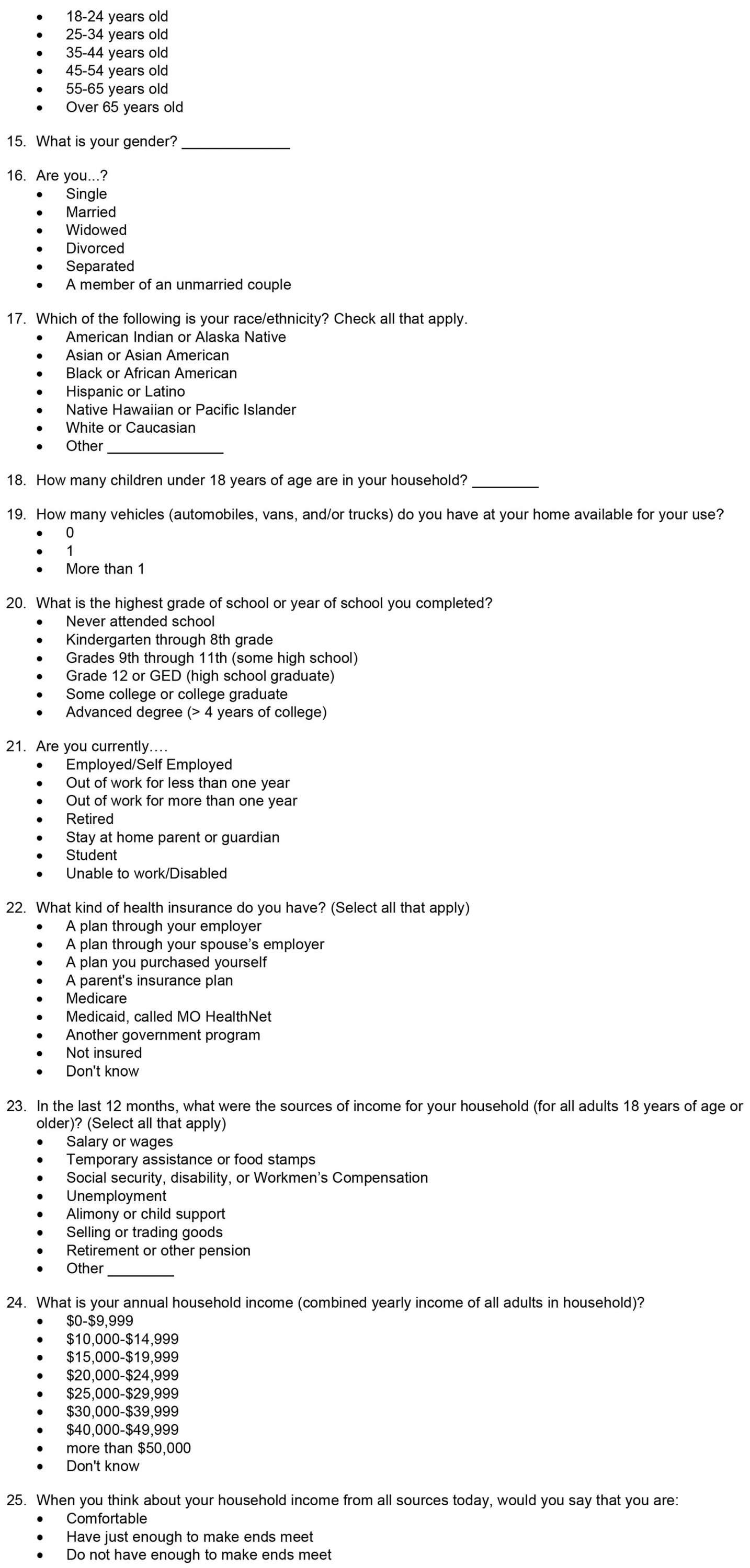

Forty-four individuals from all four study counties (Dunklin 26%, Mississippi 22%, New Madrid 26%, and Pemiscot 26%) from various backgrounds participated in the community sorting and rating phase of the study. Among these participants, 66% were female, 31% were Black/African American, and 6% were Hispanic/Latino. Additional characteristics of these participants are given in Table 2.

Table 2: Characteristics of participants in the community sorting and rating phase of the study

Characteristics of participants in the community interpretation/utilization of results

A total of 97 individuals from all four study counties (Dunklin 27%, Mississippi 15%, New Madrid 34%, and Pemiscot 24%) participated in the community interpretation/utilization of results phase of the study. Among them, 80% were female, 43% were Black/African American while 3% were Hispanic/Latino. Additional characteristics of these participants are given in Table 3.

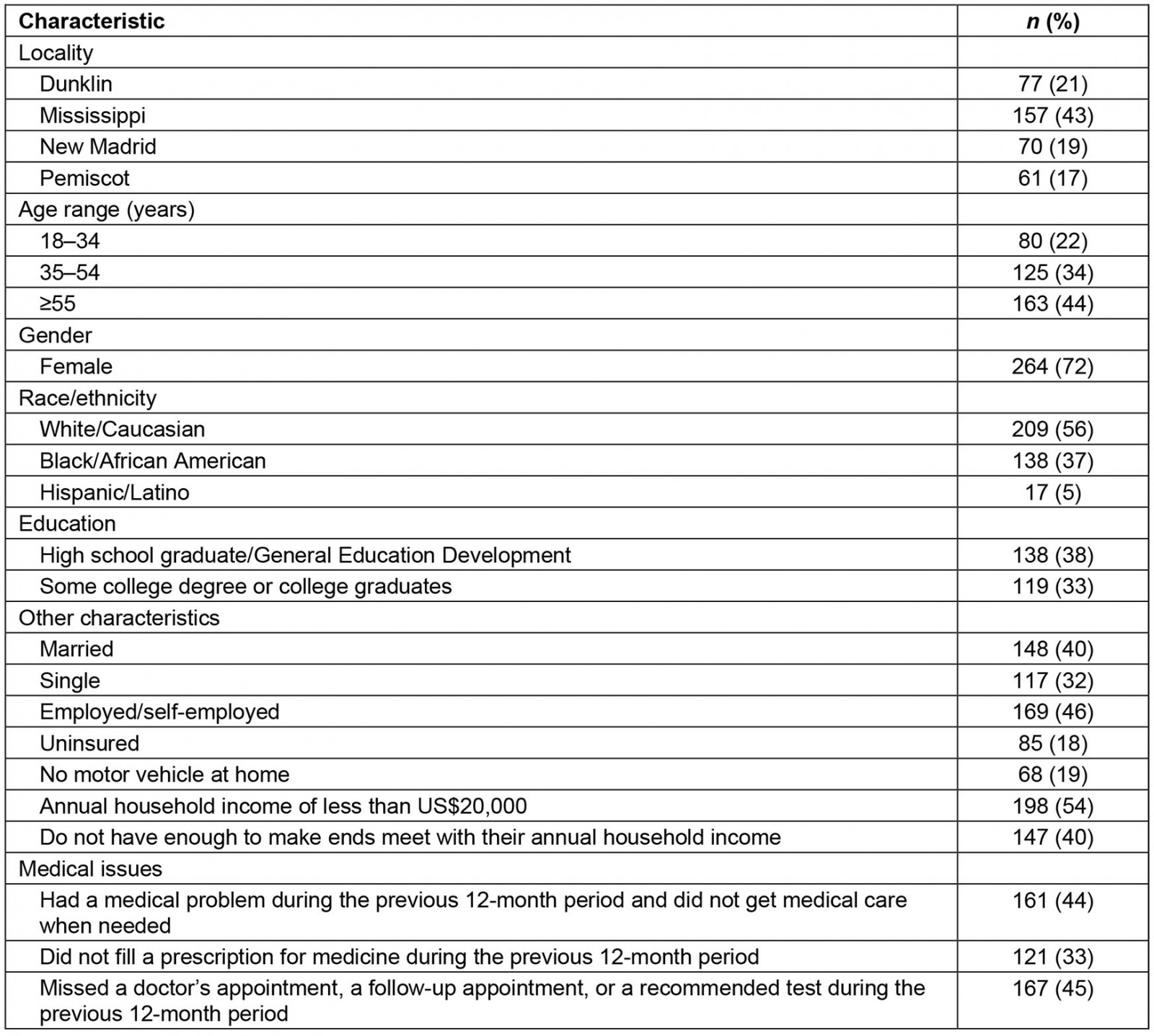

Table 3: Characteristics of participants in the community interpretation/utilization of results phase of the study

Results from concept mapping

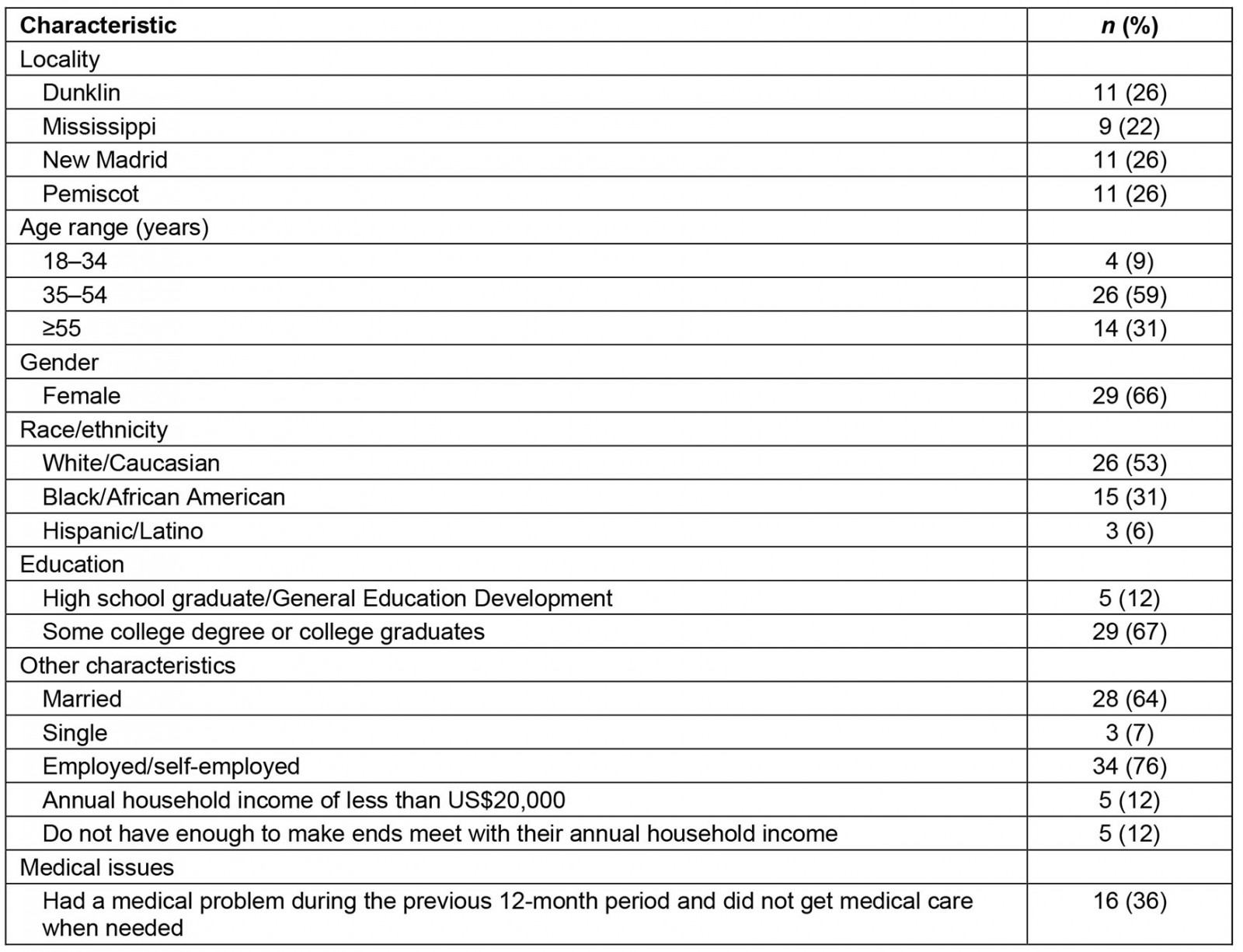

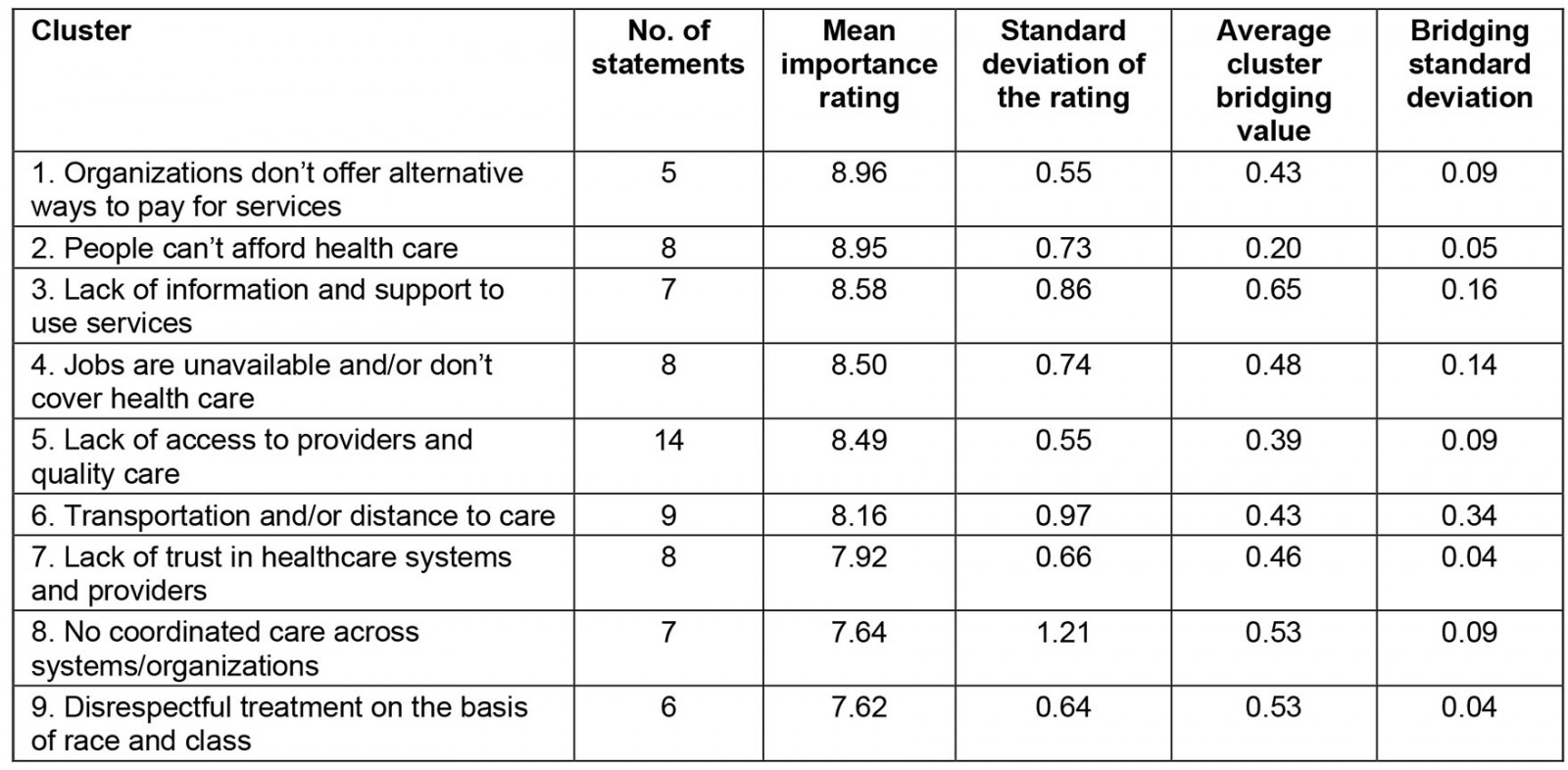

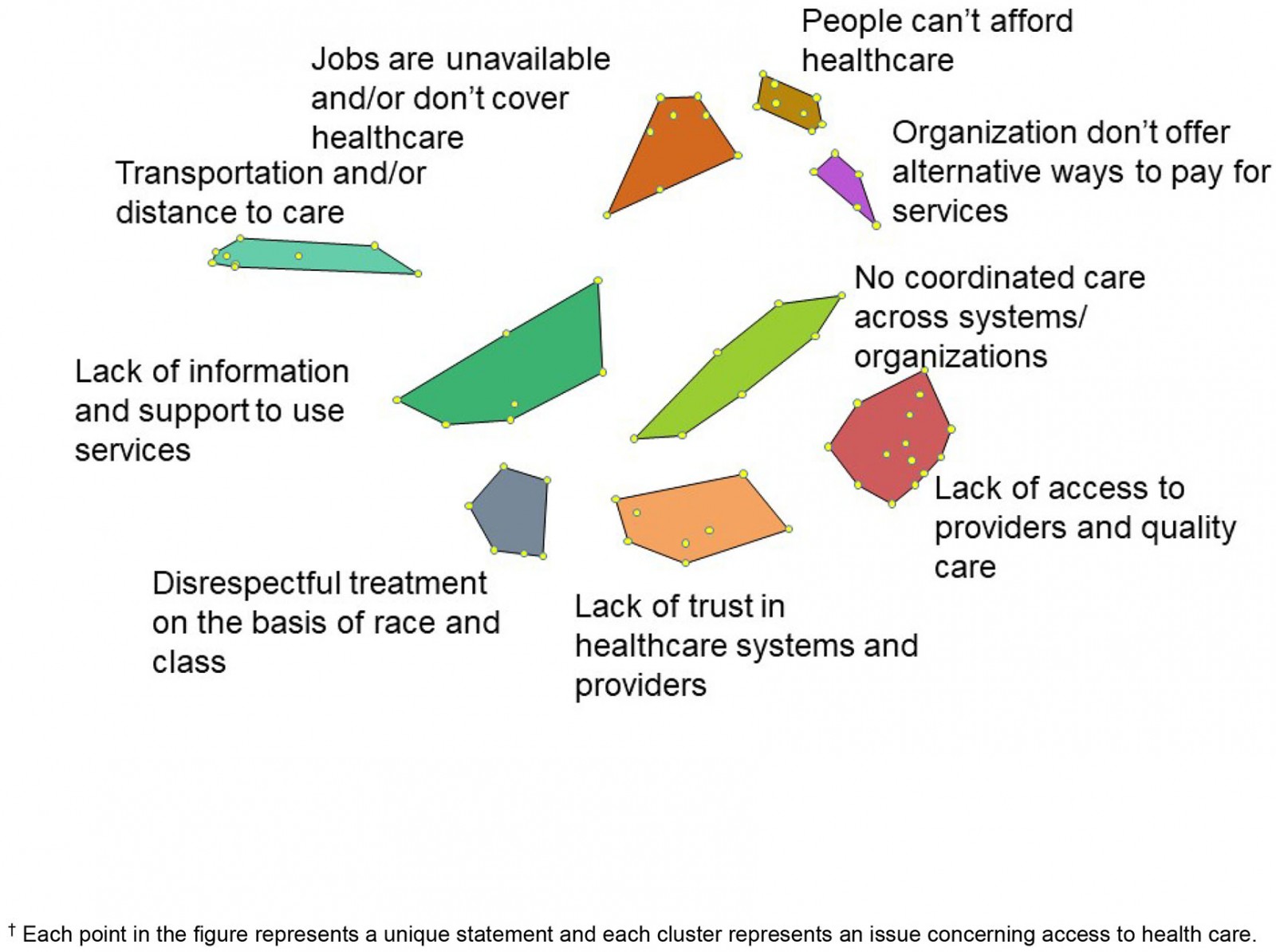

The final nine-cluster solution (Fig1) is described in Table 4, with clusters listed in order from higher to lower mean importance rating (range: 8.96–7.62; with potential importance rating of 0–10). Average cluster bridging values (range: 0.20–0.53) are also reported, reflecting the likelihood that participants sorted statements similarly (score range is 0–1 with lower values indicating greater similarity)20. A summary of each cluster with representative sample statements is described below.

1. Organizations don’t offer alternative ways to pay for services: This cluster includes five statements that were related to the payment for the services, including ‘lots of places don’t accept Medicaid’, ‘expecting payment at times of service’, and ‘no sliding scale here’.

2. People can’t afford health care: This cluster includes eight statements that were directed toward the cost of health insurance and related policies, including ‘can’t afford deductible’, ‘high cost of monthly insurance premiums’, and ‘don’t make enough money for insurance but too much for Medicaid’.

3. Lack of information and support to use services: This cluster includes seven statements pertaining to the issue of lack of awareness among community members and lack of support system in the community, like ‘people don’t know what services are available in the community’, ‘people don’t know whether they are eligible for services’, and ‘lack of support network and resources’.

4. Jobs are unavailable and/or don’t cover health care: This cluster includes eight statements that were related to jobs and the health coverage provided by the employers. For example, ‘there are no businesses or employment in my town’, ‘job doesn’t offer healthcare’, and ‘current illness caused loss of employment and health coverage’.

5. Lack of access to providers and quality care: This is the biggest cluster, with 14 statements that are related to access to healthcare services and the quality of care obtained from available healthcare institutions. Some of the statements are ‘lack of primary care doctor’, ‘not enough urgent care’, ‘quality of care is poor’, ‘don’t have some of newer technology health equipment in the area’, ‘physicians don’t always adhere to the standard of care’, and ‘long wait time to get into a doctor appointment’.

6. Transportation and/or distance to care: This cluster includes nine statements that are related to transportation issues in the area and include statements such as ‘limited public transportation’, ‘work is far from doctor’, ‘healthcare transportation only includes clients not children’, and ‘no car’.

7. Lack of trust in healthcare systems and providers: This cluster includes eight statements that pointed out the issue of lack of trust in the healthcare system and providers, such as ‘lack of confidentiality’, ‘I don’t think they really listen or care about people’s health the way they should’, ‘people don’t trust the system – medical pharmacies, providers’, and ‘providers are uncomfortable serving people of different races’.

8. No coordinated care across systems/organizations: This cluster includes seven statements that are related to multiple organizations in the region and their coordination, including ‘no coordinated care across organization’, ‘feel manipulated to pay for doctor appointment when the information could be shared over the phone’, and ‘complicated referral and billing systems’.

9. Disrespectful treatment on the basis of race and class: This final cluster includes six statements that are related to concerns of community members regarding race, respect, and stigma. This cluster includes statements like ‘I don’t like being in there like everybody nervous or judging me’, ‘not treat people with respect because of race and class’, and ‘stigma/feeling embarrassed’.

Table 4: Nine-cluster solution with mean importance rating, standard deviation of the rating, and cluster bridging value with standard deviation

Figure 1: Nine-cluster concept map created using the online concept mapping system.†

Figure 1: Nine-cluster concept map created using the online concept mapping system.†

Cluster prioritization and strategy development

Participating community members from all four counties prioritized these nine clusters based on multiple criteria presented during the meeting such as the importance to community members and organizations in their community, communal and organization support to address the cluster/issue, cost of addressing the cluster/issue (people, equipment, broadly defined resources), flexibility to address the cluster/issue, complexity to address the cluster/issue, time to address the cluster/issue, and potential impact of addressing the cluster/issue. All four counties independently identified three of the clusters as priorities for improving access to care: people can’t afford health care, lack of information and support to use services, and transportation and/or distance to care. Two of the counties added a fourth cluster: lack of access to providers and quality care.

After participants in each county prioritized the clusters, they had the opportunity to meet in small groups to begin to outline specific strategies that could be used to address the issue. Below are some strategies suggested by these participants across all four counties during each meeting.

Individuals who were part of the small group focusing on the issue of ‘people can’t afford healthcare’ discussed several strategies to address this issue including using alternative healthcare providers such as community health workers, implementing a sliding scale fee policy, building on the use of mobile health units, identifying grant-writers to help community access funds for health care, and increasing knowledge about costs and insurance coverage.

Those who focused on ‘lack of information and support to use services’ suggested creating materials to increase awareness of available resources, working with community health workers/community navigators/advocates, increasing information through existing and new locations and media channels, creating service navigation systems, and providing information for homebound by training in-home care providers.

Those who focused on ‘transportation and/or distance to care’ suggested finding ways for individuals/private transportation to serve the community, obtaining a community vehicle that can be used for transportation, obtaining funding for improving the transit system, developing alternative transportation options (‘rural UBER’), and working with local business to set out a blessing box where people can leave change that will go to transportation for health services.

Where the ‘lack of access to providers and quality care’ was prioritised, the group discussed training providers on how to interact with patients/consumers, cultural competency/humility to improve quality of care and show respect towards patients, expanding telehealth, and creating an ongoing system for sharing information about the current state of healthcare services/facilities.

Discussion

Access to care and overall health status are influenced by social and organizational factors, or what has been called social determinants of health. While secondary data can shed some light on the nature of these issues, in order to develop appropriate and feasible strategies for change, it is important to engage community members in clear articulation of their experiences and development of recommendations for change. Another aspect of community engagement is to capture the local context. All ‘rural’ is not alike, especially when understanding and addressing linkages between social determinants and healthcare access21. This extends to avoiding the pitfall of misapplying strategies that work to address social determinants in urban areas to rural areas22. Additionally, it is increasingly important to address these social determinants of health because the gaps in rural health outcomes continue to increase, as is evidenced in comparing all-cause mortality rates between rural and urban low-income Medicare beneficiaries23. Group concept mapping offers an integrated participatory mixed-methods approach to enable groups of participants to organize and represent their ideas. The present study used the group concept mapping approach to develop a shared concept of the role of social determinants in access to care and generated data that informed the development of strategies for change on a local level.

Community engagement is particularly important for outreach in remote areas and is helpful to build service delivery partnerships between local authorities and social welfare agencies. An example of a community-engaged approach to developing and testing a micro-planning strategy was applied to an outreach effort in a remote area of Mongolia. Similar to concept mapping, a strategy development process was used to analyze barriers, use mapping approaches for data analysis and problem-solving at the local level, and identify and respond to health service needs of the most difficult-to-reach subpopulation24. Another study used a similar approach to identify the perspectives of health visitors in Wales regarding a shared understanding of family resilience using group concept mapping25. The authors of the study reported they were able to achieve consensus and generate data to facilitate the development of an assessment tool to measure family resilience.

The present study findings highlighted several key issues that were identified by community participants, including that organizations don’t offer alternative ways to pay for services, people can’t afford health care, lack of information and support to use services, jobs are unavailable and/or don’t cover health care, lack of access to providers and quality care, transportation and/or distance to care, lack of trust in healthcare systems and providers, no coordinated care across systems/organizations, and disrespectful treatment based on race and class. The authors found that participants were able to apply a broad set of considerations to generate a smaller set of strategies to prioritize, using the following criteria: importance to community members and organizations in their community, communal and organization support to address the cluster/issue, cost of addressing the cluster/issue (people, equipment, broadly defined resources), flexibility to address the cluster/issue, complexity to address the cluster/issue, time to address the cluster/issue, and potential impact of addressing the cluster/issue. This resulted in consensus around the decision to focus on creating strategies to address four areas: people can’t afford health care, lack of information and support to use services, transportation and/or distance to care, and lack of access to providers and quality care. It is important to note that the other areas were also important but may have been deemed either as not as amenable to change, or that the priority areas needed to change before the other areas were tackled.

These identified issues on healthcare access are consistent with issues identified in other rural areas in the USA. For example, according to the Healthcare Georgia Foundation, the challenges affecting rural Georgians’ access to good care are lack of education, poverty, limited transportation, and unemployment26. These challenges are being tackled with the development of community health partnerships in these rural counties and Community Health Improvement Plans. Community health partnerships are most likely to be successful when voices from the community are heard, and when community members and other stakeholders are engaged through the research and strategy development process, which can be achieved by implementing methodologies like concept mapping.

Limitation

The present research identified key issues and recommendations for change. However, funding did not include the implementation of these recommendations, partly due to a shift in funding priorities that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. While recognizing the importance of funding to address emerging and emergency health conditions, the underlying social and organizational challenges identified as influencing access to care, in general, have been shown to also have impacted testing and treatment of COVID-19 in the study communities.

Conclusion

While a great deal of work has been done to identify social and organizational factors that influence access to care and health outcomes, practitioners and community members are often left with the idea that nothing can be done to address these systemic and structural issues. Participatory processes harness the synergy of community members and agencies in ways that facilitate identifying priorities and recommending approaches to shape the design of community initiatives. Without community-engaged consensus on service needs and priorities, existing programs are underutilized and unknown to the community they are designed to serve, further widening the gap in accessing health care. Community health workers are key to successful engagement, along with an approach that focuses on listening and learning. Data collection processes must be crafted in ways that allow for maximum community engagement to facilitate appropriate and feasible change efforts.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by funding from the Missouri Foundation for Health, grant number 17-0574-OF-18.

References

You might also be interested in:

2014 - Differences in media access and use between rural Native American and White children