Introduction

With accelerated digital transformation due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it is now more important than ever to understand service user views of mental health support via digital communication technologies (eg telephone, email and video-conference technologies). Digitally mediated service provision is the remote delivery of assessment, consultation and therapy via digital communication technologies by qualified professionals in health, education and social care services. As children and young people’s mental health services are family-oriented, it is important to access the views of young people as well as the views of parents/carers navigating support on behalf of their children, with indication that young people and parents/carers have overlapping and unique expectations of services (Children Act 1989 (UK))1. This has not always been the case, with a tendency to rely on parental reports2,3. There is now increasing understanding of what a good service would look like from the perspective of young people and parents/carers with regards to face-to-face mental health support4. Less is known about views and expectations of mental health support in a digital context5,6, although the common assumption is that this would be an acceptable means of accessing support for young people7.

The majority of studies of face-to-face and digitally mediated service provision in children’s mental health services have been service audits or evaluations. A review of the literature identified one study that investigated attitudes of potential users towards computerised therapy8, giving insight into acceptability and potential uptake. This self-report survey study found low interest by young people in accessing computerised therapy, whereas parents’ views were more positive. Young people’s and parents’/carers’ expectations of receiving assessment, consultation and therapy delivered by a qualified professional via digital communication technologies have not been assessed using community-based participatory approaches. By asking potential service users about their expectations of digitally mediated service provision, it is possible to not only better understand the acceptability and potential uptake, but also identify what should be delivered, monitored and evaluated based on what is important to young people and parents/carers9,10. While there are consistencies in service delivery and identified challenges, there is geographical variability in the quality of services11. Involving young people and parents/carers in a rural location, where face-to-face service delivery can be challenging, is important for increased sensitivity in the recommendations for digitally mediated service provision to meet the needs of such populations12.

The present research aimed to investigate for the first time the views and expectations of digitally mediated service provision from multiple perspectives. The research question for the present study is ‘What factors should be considered in the development and evaluation of digitally mediated service provision for children and young people with social, emotional and mental health (SEMH) needs based on young people’s and parents/carers’ views and expectations of a high quality service?’

Methods

The research was based in a large, geographically dispersed county in the UK, where more than half of the resident population live in rural areas13. This research was conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, where digitally mediated service provision was a largely unfamiliar and novel way to receive support, with the intention to explore the expectations and attitudes of potential service users with ‘insider knowledge’ of community need12, rather than to investigate the service user experience.

This was a mixed-method study using focus group and online survey methods with two separate groups of participants, within a concurrent mixed design14. A focus group was seen as the optimal approach, although the study topic is well suited to survey and focus group approaches. The first group of participants comprised looked after children and care leavers (children who have been in the care of their local authority) who were approached about participating in a focus group conducted in person as part of a shared Children in Care Council (CiCC) and corporate parent session. The second group comprised parents/carers of primary-aged children with SEMH difficulties. Parents/carers were invited to attend a focus group, but the response rate was very low. For methodological pragmaticism15,16, participation was offered through an online survey, which could be completed at home in participants’ own time. Recruitment was made via the local Parent/Carer Council, internal communications in the local authority and a resource page for schools. Parents/carers could choose to enter a prize draw with the chance to win £50 (~A$90).

Five young people aged 16–19 years (two males and three females) attended a focus group, two of whom had accessed at least one specialist health, education or special educational needs and disability (SEND) service. Eighteen parents/carers (aged 27–62 years old) took part in the survey, completed by one parent/carer (mother) in 16 cases and by mother and father in two cases. Fourteen were parents/carers of children who had accessed at least one specialist health, education or SEND service.

The content of the focus group and survey was co-produced with members of the local commissioning team specialising in youth voice and the Parent/Carer Council. Participants were asked to rank six statements in terms of what was most important to them when accessing a specialist service: ‘feeling listened to’, ‘feeling supported’, ‘getting help quickly’, ‘having a say in your care’, ‘having a written plan’ (parent/carer)/‘having a better time’ (young person) and ‘knowing what the next step is’. The statements relate to service priorities endorsed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in the UK, and other quality standards17. Participants were asked about their views of using video-based interaction and digital communication technologies for remote assessment, consultation and therapy.

The same questions and structure were used across methods to ensure that the data would be reasonably comparable. For the ranking of key service dimensions in the focus group, young people were asked (as a group) to order speech bubbles on sheets of paper containing the six statements with the most important statement(s) at the top. For the survey, parents/carers were asked to order the items by importance, with the item that mattered most to them at the top. For the questions about digitally mediated service provision, parents/carers completing the survey were asked to provide ratings to show their agreement with the helpfulness of this support on a seven-point Likert scale (where 1=’strongly disagree’ and 7=’strongly agree’). For each question on the survey, additional space was provided for parents/carers to add information. The focus group data-recording methods also enhanced comparability between analyses, with information captured using sticky notes, flipchart paper and brief notes rather than recording and transcription of the discussion.

Focus group and qualitative survey responses were analysed separately, using content analysis18. Descriptive statistics were used to illustrate views about service dimensions. Expectations of digitally mediated service provision were categorised as preferences, positives and negatives. A coding framework was developed to generate statements that reflected the participants’ responses (words and phrases) recorded on flipcharts or free-text comments18. The statements were reviewed and checked for overlap with other statements and against the data.

Ethics approval

This research received full ethics approval from the University of Bath Department of Psychology Research Ethics Committee (PREC code: 190-40). Participants were asked to give written informed consent. Parents/carers of participants aged less than 18 years had previously been asked to consent to each young person’s participation in CiCC activities, including research, as part of their youth group membership.

Results

Perceptions of service priorities

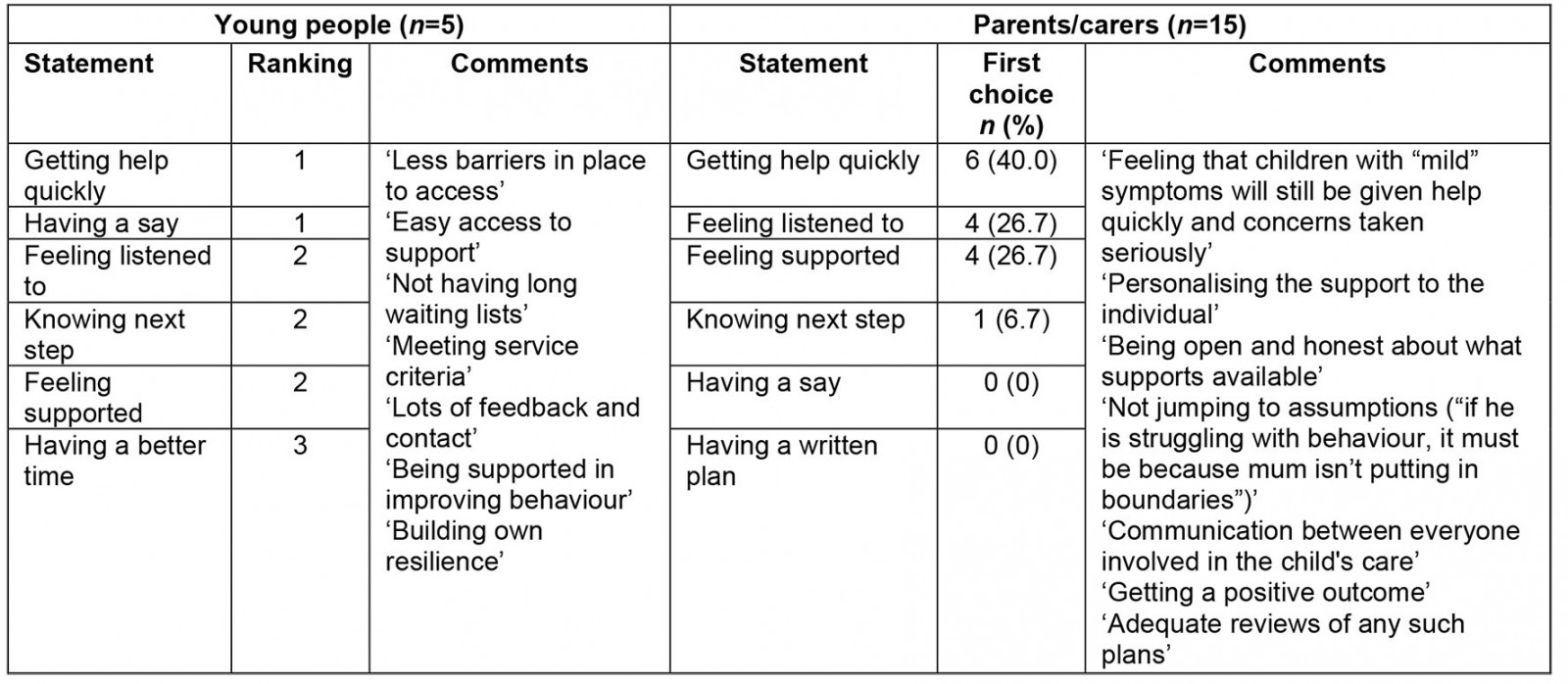

Table 1 shows the rank order of six statements of service dimensions by young people, and the number and percentage of parents/carers voting for one of six statements as their first choice, with selected comments.

Table 1: Ranking of statements relating to service dimensions with participant comments

Young people: When asked to order six statements in terms of importance as a group, participants indicated that some statements were of equal importance, therefore the final ranking was 1 to 3. Getting help quickly and having a say in their care were the most important to participants when accessing and receiving support. Participants expanded on the six statements, highlighting the need to be supported, to have lots of contact and feedback, and to have easy access to support.

Parents/carers: Getting help quickly was selected as the most important statement by the largest percentage of participants. The qualitative survey responses highlighted that it is important to parents/carers that services help to support a positive outcome including a better understanding of their child’s needs, a sense of working together between all involved in the child’s care, and open and non-judgemental communication.

Attitudes toward digitally mediated service provision

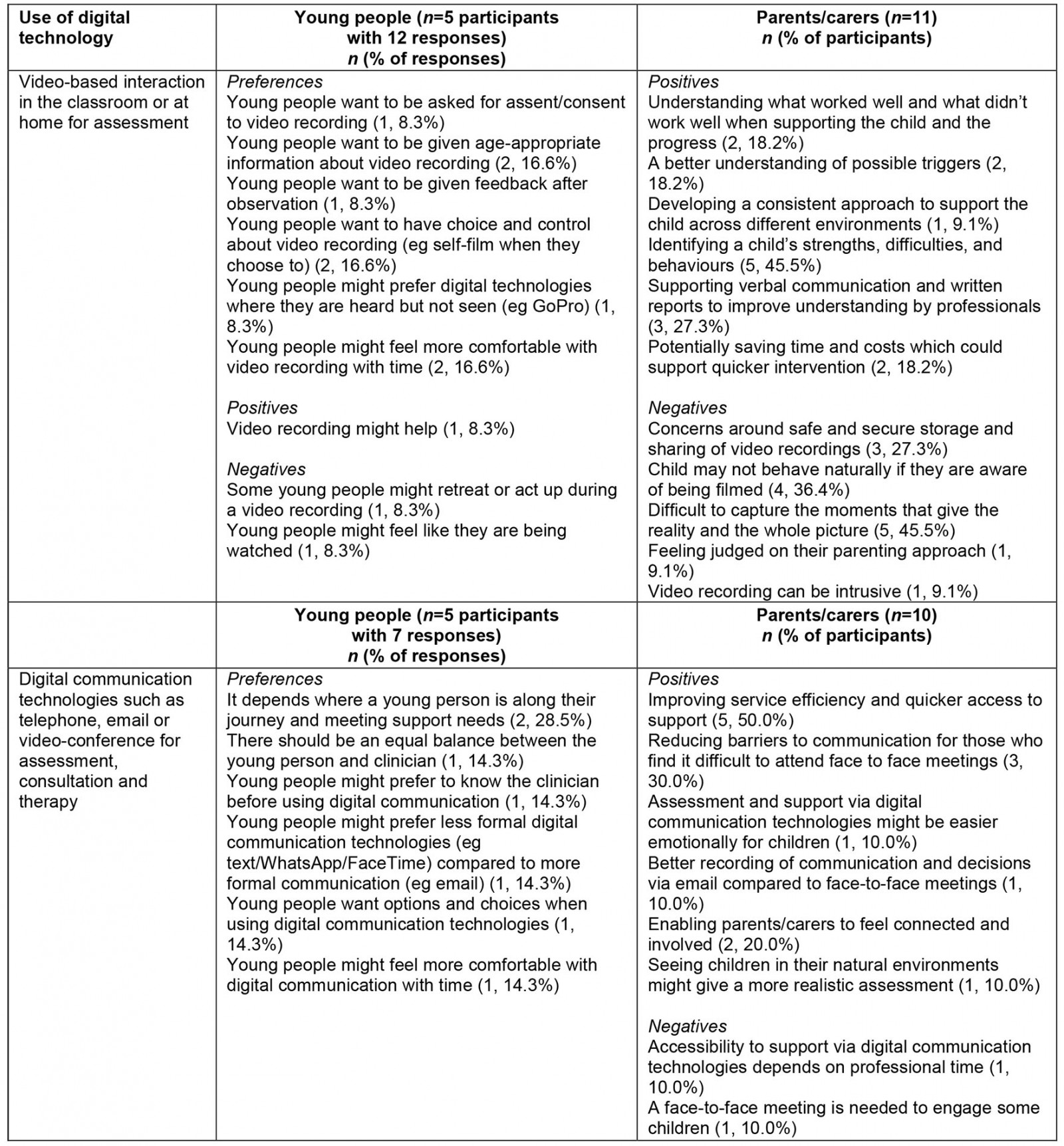

Table 2 shows the elicited statements by young people and parents/carers.

Table 2: Attitudes toward digitally mediated service provision

Young people: The five participants gave feedback on their views of video-based interaction in the classroom or at home for remote assessment (nine elicited statements from 12 group responses) and views of using digital communication technologies for remote assessment and therapy (six elicited statements from seven group responses).

Parents/carers: In response to a statement regarding whether video-based interaction would be helpful in the classroom or at home for remote assessment, 13 participants (76.5% of 17 participants) selected an ‘agree’ option on a seven-point Likert scale. One participant (5.9%) strongly disagreed. Of the 17 responses, 11 (64.7%) responses included free-text responses to this statement. In response to a statement regarding whether it would be helpful to use digital communication technologies for remote assessment and consultation about their child and the support provided at school and at home, 14 participants (82.4% of 17 participants) selected an ‘agree’ option on a seven-point Likert scale. Two participants (11.8%) strongly disagreed. Of the 17 responses, 10 (58.8%) included free-text responses to this question.

Discussion

The findings of this research suggest that digitally mediated service provision should be timely and patient-centred to be considered acceptable by young people with SEMH needs and their parents/carers. Young people and parents/carers in this research had overlapping and unique expectations of digitally mediated service provision. Having a say in their care was important to young people and feeling listened to was important to parents/carers. This study adds to the limited evidence base examining young people’s and parents’/carers’ expectations of digitally mediated service provision5,6.

Key indicators for evaluation: meeting the expectations of service users

Quick access to support was important to young people and parents/carers. Perceived benefits of digital communication for study participants in a rural location included more efficient and accessible services. It is not clear whether these perceptions of a more efficient and accessible service are borne out in reality. Although there are time-saving benefits related to the removal of travel time for professionals in rural locations, there needs to be consideration of the invaluable ‘thinking space’ for professionals during travel time19, with implications for how the time is reallocated. Evaluations of digitally mediated service provision should measure service efficiency (eg the number of children seen, or waiting time) in comparison to face-to-face service provision and the perceived ease of access as elements of accessibility.

Findings from the current research and previous research5,20 indicate that digitally mediated service provision may only be acceptable if young people have self-control and agency and parents/carers feel involved. This was borne out in the present research; with low response by parents/carers to attend a focus group, the use of digital technology allowed greater involvement. Young people also identified factors that might help them to feel more comfortable with digital communication over time, which is important for implementation in rural locations where it may not be feasible to offer an initial face-to-face session due to geographic dispersion. Factors included the developing therapeutic relationship and increasing familiarity with the digital context, as well as the support needs of the individual service user and where they are along their journey. Digitally mediated service provision is conceptually different to face-to-face service provision21, and it is therefore of interest to consider in what ways patient-centred support is manifested in this different context and young people’s teletherapeutic preferences for maintaining the therapeutic relationship. Measures of service user experience should include questions about the therapeutic alliance22, with a focus on partnership working as well as affective elements.

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of the present research is the involvement of both a group of young people and a group of parents/carers of primary-age children to inform service development and evaluation. However, it was not possible to directly obtain the views of young children in this research. There are well-documented challenges of engaging young children (4–8 years), such as their reflective capacity and ability to respond to open-ended questions23,24. After reviewing the literature, while service experience survey measures and other more creative methodologies were identified for use with pre-adolescent children (9–12 years)25-27, no appropriate measures were identified for young children (4–8 years). Furthermore, the findings of this study are limited by small sample sizes. In terms of parent/carer representation, the survey response rate is unknown. Therefore, we do not know the extent to which the views of the current sample are representative of younger children or the wider population of parents. The depth of the current qualitative analysis was limited by the data-recording methods, and the data were analysed by one coder with potential problems of legitimation (dependability or reliability) for this mixed-method research. Further qualitative research with larger samples is required for in-depth exploration of young people’s and parents’/carers’ views of digitally mediated service provision5,7.

Conclusion

The findings of this research are relevant to understanding the views of potential service users of digitally mediated service provision in a world that has experienced COVID-19, with a view to developing services that meet the needs and expectations of those accessing remote mental health support for the first time. Accessibility and patient-centredness were found to be key dimensions of digitally mediated service provision, and particularly relevant for rural settings. The appropriateness of one-size-fits-all models of service delivery, including digitally mediated service provision and face-to-face service provision, should be considered in the future development of children’s and young people’s mental health services.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this study came from a PhD studentship funded by the county council.

References

You might also be interested in:

2011 - Colorectal cancer screening among rural Appalachian residents with multiple morbidities

2009 - What older people want: evidence from a study of remote Scottish communities